Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DANJUMA ABDU YUSUF | -- | 1767 | 2023-08-04 06:53:12 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1767 | 2023-08-04 07:21:57 | | | | |

| 3 | DANJUMA ABDU YUSUF | + 6 word(s) | 1773 | 2023-08-10 10:40:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Yusuf, D.A.; Ahmed, A.; Zhu, J.; Usman, A.M.; Gajale, M.S.; Zhang, S.; Jialong, J.; Hussain, J.U.; Zakari, A.T.; Yusuf, A.A. Cultural Heritage Sites in Kano. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47652 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Yusuf DA, Ahmed A, Zhu J, Usman AM, Gajale MS, Zhang S, et al. Cultural Heritage Sites in Kano. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47652. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Yusuf, Danjuma Abdu, Abubakar Ahmed, Jie Zhu, Abdullahi M. Usman, Musa S. Gajale, Shihao Zhang, Jiang Jialong, Jamila U. Hussain, Abdullahi T. Zakari, Abdulfatah Abdu Yusuf. "Cultural Heritage Sites in Kano" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47652 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Yusuf, D.A., Ahmed, A., Zhu, J., Usman, A.M., Gajale, M.S., Zhang, S., Jialong, J., Hussain, J.U., Zakari, A.T., & Yusuf, A.A. (2023, August 04). Cultural Heritage Sites in Kano. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47652

Yusuf, Danjuma Abdu, et al. "Cultural Heritage Sites in Kano." Encyclopedia. Web. 04 August, 2023.

Copy Citation

Historical buildings have inhabited every epoch of history. Some of these built legacies are now in ruins and dying whilst others are somewhat undamaged. Knowledge of conservation techniques available today has allowed us to understand more innovative ways of conserving the built heritage. Such techniques are, however, incompatible with the building materials available in our historical epoch and environment. People seek to reclaim the forgotten cultural heritage in the midst of the heritage conservation era while bearing in mind that previous work seldom takes into account the inventive preservation methods of today.

Kano metropolis

Historic Urban Landscape (HUL)

cultural heritage

Hausa traditional architecture

Traditional building materials

1. Cultural Heritage Sites in Kano, Nigeria

In most cities of the developing nations, using Nigeria as a model, the drastic increase of economic routine and quest for prime land in the metropolitan areas threaten the survival of aging reserved monument sites. It has as well been noted that natural and cultural heritage are ever more endangered through devastation by the traditional causes of decay and by transforming social and economic circumstances which intensify the situation of this stock with the phenomena of destruction and damage [1][2].

Cultural heritage in Kano is visible from the perspective that the ancient city is sheathed by the fortification wall, having three local administration expanses known as Dala, Gwale, and the Kano Municipal. The Kano Emirate in the eleventh century was a fundamental piece of the world economy, specifically in Africa, bringing together different commercial goods such as cowhide, iron, and cotton materials to mention but a few. As a result of the blow-up in the Nigerian economy and periodic growth in the number of inhabitants, Kano city could not accommodate strangers, which necessitated protecting the city and further encouraged the building of city walls to safeguard the residents from attack [3].

The old Kano cultural landscape has a compositional layout and a fortunate story that pulls in universal interest in the city. As portrayed in Figure 1, Kano is the greatest enduring stronghold of many cultural sites and events in the west of Africa. Adamu [3] further asserts that the Kano walls were founded based on the vigor of winning wars. The erection of these walls commenced with the work of Sarki Gijimasu in 1100 AD, and was carried on by Sarki Mahammadu Rumfa (1463–1499), Sarki Mahammadu Nazaki (1618–1623), and in 1834–1937 there was further opening out to allow development. These walls were pronounced national landmarks in 1959, with the National Commission for Historical Centers and Landmarks being in control [3].

Figure 1. Kano Durbar, an annual festival. Source: Authors’ Fieldwork, 2021.

Kano city’s cultural sites were recorded by UNESCO among world heritage sites in its tentative list [3]. They further emphasized that, in 2007, the National Commission of Museums and Monuments (NCMM) are responsible for the protection of the Emir of Kano’s royal palace, revealing the UNESCO world heritage order of the city’s revitalized walls, royal residence, and other prominent places. Over a decade of such acknowledgments by UNESCO, action on the proposal remains immobile and history specialists are alarmed that the unrelenting harm to the strongholds could put in them further danger. The remaining fractions of the revitalized walls of Kano are more imperilled with devastation than at any time in the modern era because of civic strategies that give little concern to heritage conservation. Below are some of the historic sites in Kano.

- a.

-

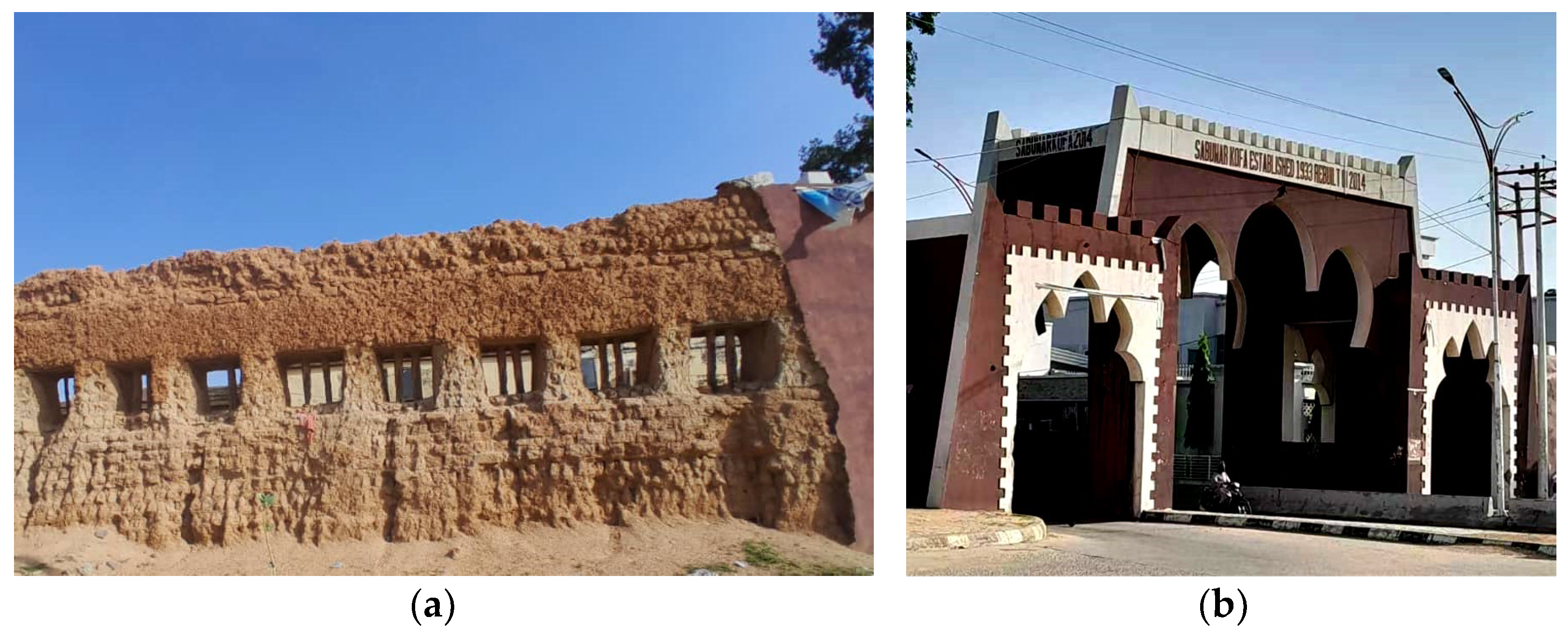

City wall and gates: the gates which have 15 doors, as reviewed, entail 8 traditional entryways (erected with mud), 6 modernized doors (reconstructed in concrete), and 1 present-day door (ongoing project with concrete). Nevertheless, the Kano city wall remains a good-natured declaration of African indigenous deployment of its engineering to distinguish political space, as a safeguard and defence structure, a working alliance, and the executive, to mention a few (see Figure 2).

- b.

-

Kurmi Market was the foremost and principally recognized marketplace that has been in existence as long as the old Kano city. Its planning was astounding and innovative in the engineering development in the design of the market layout. While investigation reveals that it was rarely conserved, relatively it has undergone a few transformations to the level that it has mislaid its historic signature to unnecessary modernism [4].

- c.

-

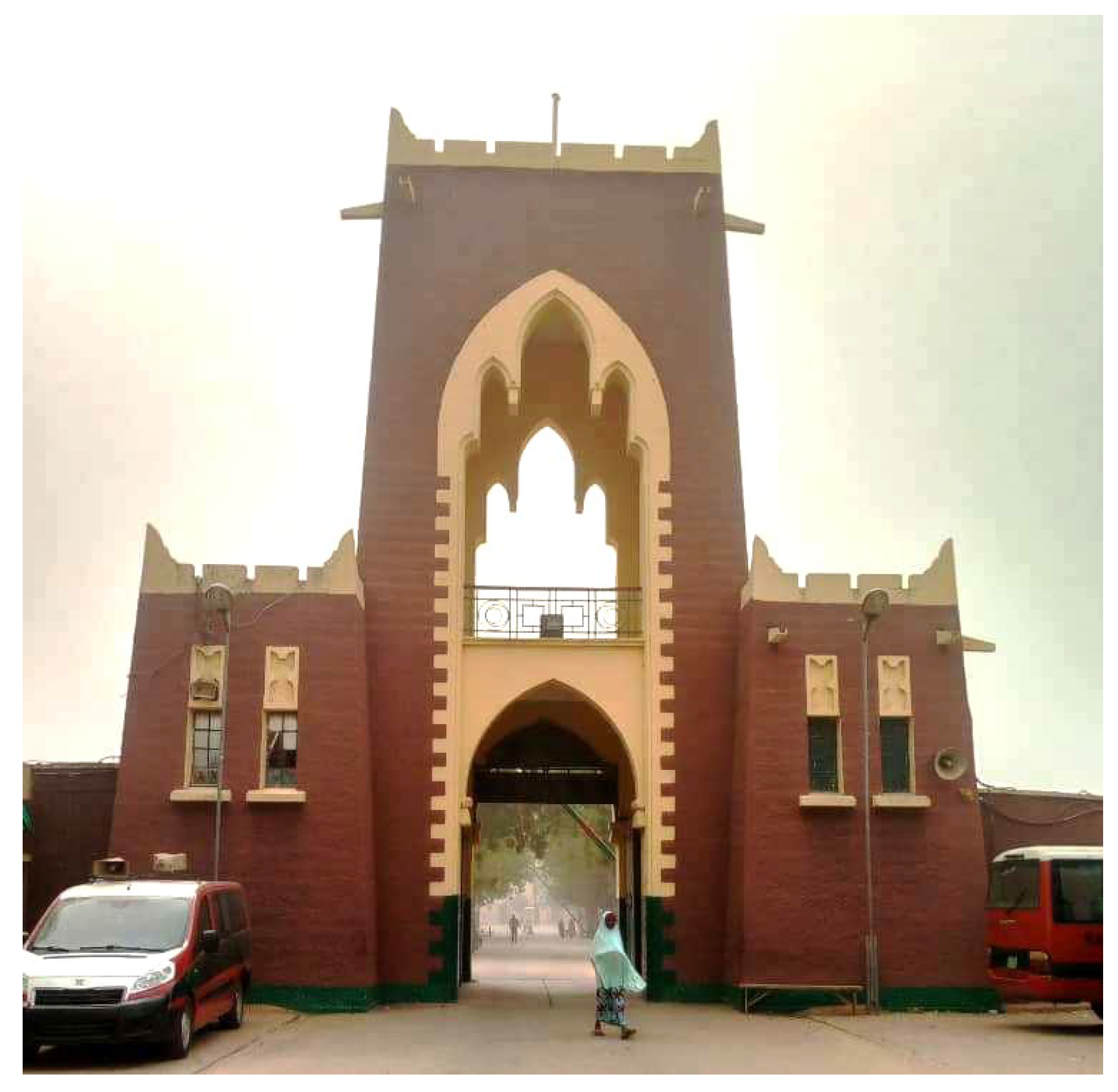

Kano Emir’s Palace was founded by the Emir of Kano, Sarki Muhammadu Rumfa, who ruled from 1463 to 1499. The palace has three doorways, to be precise Kofar Fatalwa, Kofar Kwaru, and Kofar Kudu (shown in Figure 3). The palace is divided into three fragments; the administrative structure with spaces (Rumfar Kasa, Soran Zauna Lafiya, Soron Bello, and Soron Giwa) is situated in the south. The focal fraction entails the Emir’s family while the northern parts remain for the servants’ and workers’ quarters [3].

Figure 2. (a) Eroded part of the ancient Kano city wall. (b) One of the rehabilitated city gates in 2014. Source: Authors’ Fieldwork, 2023.

Figure 3. Kofar Kudu, one of the prominent entrances of the Emir’s Palace in Kano. Source: Authors’ Fieldwork, 2023.

2. Contemporary Methodologies for the Conservation of Architectural Heritage

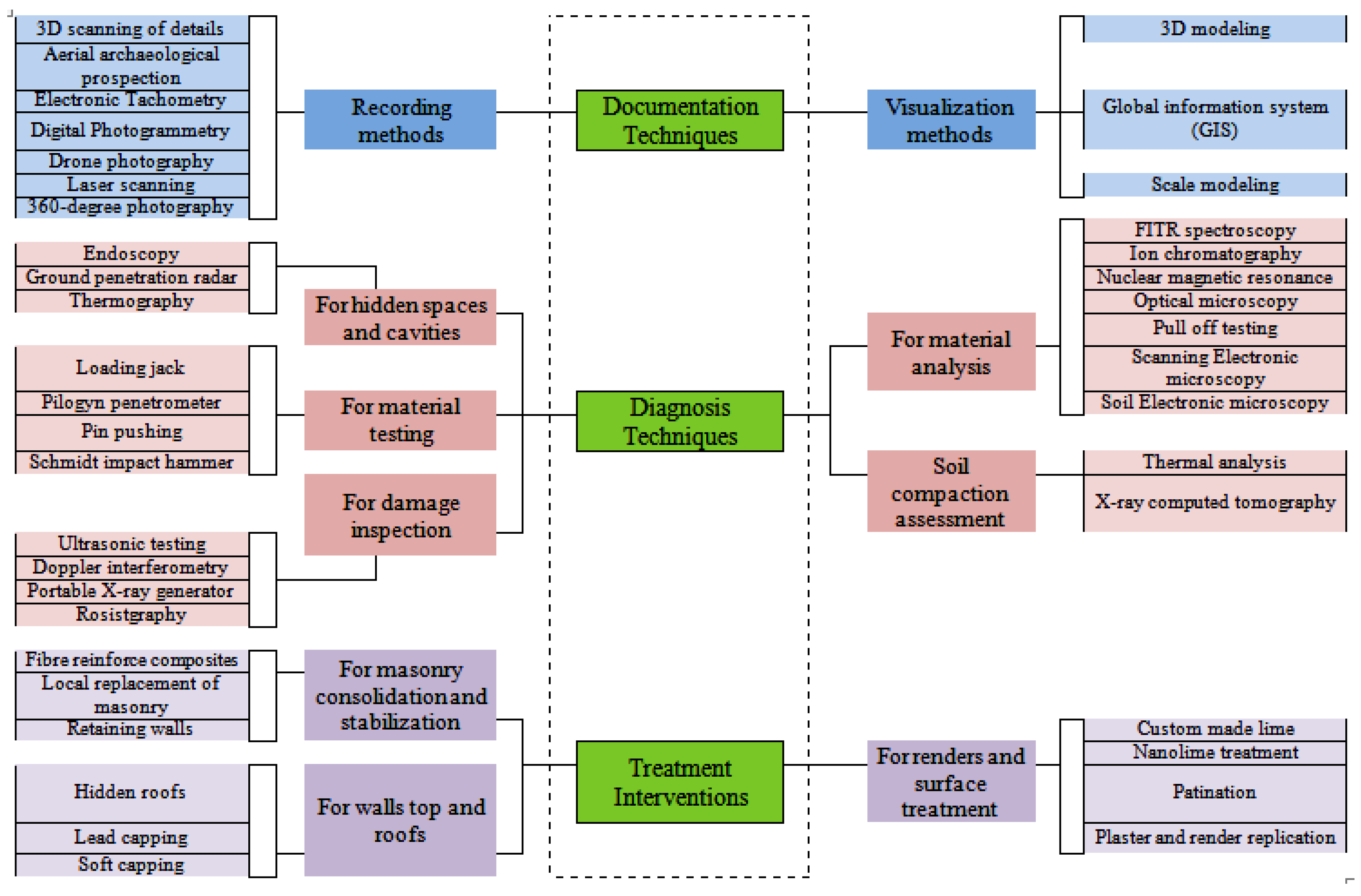

Inventive technologies have been used in the conservation of heritage buildings around the world with proven efficacy [5][6][7]. These methods include documentation, diagnostic, and treatment, where many of the techniques have proved to be non-destructive and productive.

The non-destructive techniques of heritage conservation make it possible to achieve the quantitative and qualitative aspects required for heritage buildings’ preservation, though such techniques can be elusive and time consuming [8]. Moreover, conservation procedures are classified into three [8][9][10][11] as highlighted below.

Figure 4 shows the details of different techniques required for the conservation of architectural heritage.

Figure 4. Innovative methodologies in preservation and restoration.

2.1. Documentation Techniques

Documentation techniques include surveying heritage buildings and recording the elements required for visualization of the reflected subject to be handed to the conservationist. Such documentation methods entail observation, recording, and unveiling the data [12]. Documentation is, simply put, recording and visualization methods [9] (see Figure 4). Ref. [13] considered the image-based scheme as limited and purposely meant to capture and store only the photographic data. A combinative process, on the other hand, benefits from both image and non-image-based schemes, and, therefore, is a better option.

Furthermore, conservation processes require an understanding of the authenticity, value, and significance attached to the emotional as well as the physical characteristics of the heritage entity [14]. Gathering information on the physical conditions such as the state of the materials is, therefore, essential; it also includes examining the microstructure, chemical constituents, and morphological characteristics of the built heritage [13].

2.2. Diagnostic Methods

A diagnostic method involves examining the recorded deficiency for further treatment of the deterioration and decay.

Research by [8][15] unveiled the integrated and multiple ideas in the diagnosis of a putrefied built structure. The use of a three-dimensional terrestrial laser scanner was applied to examine the classification, origin, development, and history of the stone utilized in the construction, an ultrasonic measurement verified the stone size to find out the elasto-mechanical strength. Infrared thermography was used to examine the temperature of the built heritage through its surface. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and optical microscopy (OM) were used to potentially reveal the porosity, type of stone, and existence of microbes. SEM and OM can differentiate materials, identify possible biodeteriogens, and demonstrate the space and surface allotment of possible biodeteriogens [6][11]. Material classification provides the possible type of stone applied in the construction, its pore size and grain size, all of which authenticate the exposure of heritage buildings to deterioration [15][16].

Non-invasive and non-destructive methods are used to perform diagnosis, as highlighted by [17]. They [17][18] also emphasized that these techniques do not destroy the underlying material, which makes them advantageous. The materials used in these methods include nitrocellulose membranes [19], adhesive tapes [20], and sterile scalpels [21].

A Raman spectrometer was primarily used in the previous conservation works, but often does not have the proper report for the treatment carried out. This makes it unique in its potential to recognize the conservation executed [22][23]. It is often selected for in situ analysis when finding out the organic and inorganic subject on a stone bedrock. X-ray diffraction verifies the structure of natural compounds and the nature of a crystalline compound as well [24]. Nevertheless, it is avoided in some cases because of its destructive nature [12].

Some novel molecular-based diagnostic methods adopted in cultural heritage preservation include omics: genomics and proteomics. Genomics provides information on microorganisms that live in deteriorated heritage, as well on the biodeteriogens living on the heritage site [20][25][26]. Ref. [27] emphasizes the application of this method as it illustrated the array of microbes on stone monuments surrounding the UNESCO world heritage site at the West Lake Cultural Landscape of Hangzhou, where cyanobacteria were discovered as the likely biodeteriogens. The use of proteomics before conservation work is of assistance since it recognizes organic binders applied in paintings on a heritage substance or earlier conservation treatments [28]. A Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer recognizes organic and inorganic materials (in some cases) while sodium dodecyl sulphate→polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS→PAGE) isolates and recognizes the specific protein available in the organic substance.

Conservation of architectural heritage begins with an appropriate examination of the building and structural components to establish the basis of the degradation and its extent alongside the proper conservation treatments to be applied [29][30]. The initial evaluation is through physical inspection, in which conservationists with architects assess the decay visually, without devices. Even though this is a necessary step, it does not provide specific information concerning the history or decomposition in progress, for this reason, the call for informative diagnostic tools and skills are essential.

Nevertheless, proteomics is the best technique due to its productive act on the conservation of painted built heritage in Nigeria, because of its novel recognition of organic binders applied in paintings on a heritage substance or earlier treatments’ interventions.

2.3. Treatment Interventions

There are many approaches to the restoration of the built heritage with treatment intervention methods [12]. Nanotechnology methods have been broadly utilized in the conservation of built heritage as consolidants [31], cleaning agents [5], and biocides [32]. The biocides were implanted in a tetraethyl oxysilane (TEOS), water-repellent consolidant, and/or siloxane-based substance; Estel 1100, SILO III, and TEOS are nanocomposite materials which consolidated the weathered stone [12]. Ref. [33] further noted that it builds up a copper polymer organo-composite that has bacteriostatic and antifungal actions that were discharged slowly for a certain time.

Biotechnology, in the context of the restoration of cultural heritage, has been popular for more than ten years [34] and also has been used in developed nations [35]; however, it is yet to be implemented in Nigeria [12]. The benefit of biorestoration over many traditional treatments lies in its harmlessness to professionals, its eco-friendliness, non-destructiveness, precision, and efficiency [36].

Hence, the advanced techniques in the conservation of cultural heritage include nanotechnology, bio-conservation (biotechnology), and laser technology, among others, which are used due to their efficiency, safety, and ecological nature.

References

- UNESCO. Convention concerning the protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage-being World Heritage. In Proceedings of the General Conference, 17th Session, Paris, France, 17 October–21 November 1972.

- Yusuf, D.A.; Zhu, J.; Saleh-Bala, M.; Yakubu, A.; Nashe, A.S. Evolutionary trends in landscape of Hausa Open spaces: The key enablers of “Habe” cities planning mythology. J. Reg. City Plan. 2023, 34, 22–38.

- Adamu, H.S. An Analysis of Cultural Heritage Conservation in Kano, Nigeria. Master’s Thesis, North East University, Nicosia, Cyprus, 2020.

- Iliyasu, I.I. Challenges of preservation of cultural landscapes in traditional cities: Case study of kano ancient city. In Proceedings of the International Council for Reseach and Innovation in Building and Construction (CIB), Lagos, Nigeria, 28 January 2014; pp. 1–12.

- Kapridaki, C.; Verganelaki, A.; Dimitriadou, P.; Maravelaki-Kalaitzaki, P. Conservation of Monuments by a Three-Layered Compatible Treatment of TEOS-Nano-Calcium Oxalate Consolidant and TEOS-PDMS-TiO2 Hydrophobic/Photoactive Hybrid Nanomaterials. Materials 2018, 11, 684.

- Moropoulou, A.; Zendri, E.; Ortiz, P.; Delegou, E.T.; Ntoutsi, I.; Balliana, E.; Becerra, J.; Ortiz, R. Scanning Microscopy Techniques as an Assessment Tool of Materials and Interventions for the Protection of Built Cultural Heritage. Scanning 2019, 2019, 5376214.

- Yusuf, D.A.; Ahmed, A.; Sagir, A.; Yusuf, A.A.; Yakubu, A.; Zakari, A.T.; Usman, A.M.; Nashe, A.S.; Hamma, A.S. A Review of Conceptual Design and Self Health Monitoring Program in a Vertical City: A Case of Burj Khalifa, U.A.E. Buildings 2023, 13, 1049.

- ICE. Report Assessing Innovative Restoration Techniques, Technologies and Materials Used in Conservation; Bláha, J., Novotný, J., Eds.; Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics of the Czech Academy of Sciences: Prague, Czech Republic, 2018.

- Stylianidis, E.; Remondino, F. 3D Recording, Documentation and Management of Cultural Heritage; Whittles Publishing Dunbeath: Caithness, UK, 2016.

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.-C.; Hou, M.; Li, A. Recent progress in instrumental techniques for architectural heritage materials. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 36.

- Hassani, F.; Moser, M.; Rampold, R.; Wu, C. Documentation of cultural heritage techniques, potentials and constraints. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 40, 207.

- Okpalanozie, O.E.; Adetunji, O. Architectural Heritage Conservation in Nigeria: The Need for Innovative Techniques. Heritage 2021, 4, 120.

- ICOMOS. Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 14th General Assembly, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 27–31 October 2003; pp. 27–31.

- Adetunji, O.S.; Essien, C.; Owolabi, O.S. eDIRICA: Digitizing Cultural Heritage for Learning, Creativity, and Inclusiveness; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018.

- Fais, S.; Casula, G.; Cuccuru, F.; Ligas, P.; Bianchi, M.G. An innovative methodology for the non-destructive diagnosis of architectural elements of ancient historical buildings. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4334.

- Gadd, G.M.; Dyer, T.D. Bioprotection of the built environment and cultural heritage. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 1152–1156.

- Urzì, C.; De Leo, F.; Bruno, L.; Krakova, L.; Pangallo, D.; Albertano, P. How to control biodeterioration of cultural heritage: An integrated methodological approach for the diagnosis and treatment of affected monuments. Work. Art Conserv. Sci. Today 2010, 1, 1–9.

- Okpalanozie, O.E.; Adebusoye, S.A.; Troiano, F.; Polo, A.; Cappitelli, F.; Ilori, M.O. Evaluating the microbiological risk to a contemporary Nigerian painting: Molecular and biodegradative studies. Intern. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 114, 184–192.

- Pepe, O.; Sannino, L.; Palomba, S.; Anastasio, M.; Blaiotta, G.; Villani, F.; Moschetti, G. Heterotrophic microorganisms in deteriorated medieval wall paintings in southern Italian churches. Microbiol. Res. 2010, 165, 21–32.

- Urzı, C.; De Leo, F. Sampling with adhesive tape strips: An easy and rapid method to monitor microbial colonization on monument surfaces. J. Microbiol. Methods 2001, 44, 1–11.

- Polo, A.; Gulotta, D.; Santo, N.; Di Benedetto, C.; Fascio, U.; Toniolo, L.; Villa, F.; Cappitelli, F. Importance of subaerial biofilms and airborne microflora in the deterioration of stonework: A molecular study. Biofouling 2012, 28, 1093–1106.

- Vazquez-Calvo, C.; Martinez-Ramirez, S.; Alvarez de Buergo, M.; Fort, R. The use of portable Raman spectroscopy to identify conservation treatments applied to heritage stone. Spectrosc. Lett. 2012, 45, 146–150.

- Casadio, F.; Daher, C.; Bellot-Gurlet, L. Raman spectroscopy of cultural heritage materials: Overview of applications and new frontiers in instrumentation, sampling modalities, and data processing. Anal. Chem. C Herit. 2016, 374, 62.

- Herrera, L.K.; Le Borgne, S.; Videla, H.A. Modern methods for materials characterization and surface analysis to study the effects of biodeterioration and weathering on buildings of cultural heritage. Intern. J. Arch. Herit. 2008, 3, 74–91.

- Piñar, G.; Dalnodar, D.; Voitl, C.; Reschreiter, H.; Sterflinger, K. Biodeterioration risk threatens the 3100 year old staircase of Hallstatt (Austria): Possible involvement of halophilic microorganisms. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148279.

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Pan, X.; Ge, Q.; Ma, Q.; Li, Q.; Fu, T.; Hu, C.; Zhu, X.; Pan, J. Identification of fungal communities associated with the biodeterioration of waterlogged archeological wood in a Han dynasty tomb in China. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1633.

- Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Ge, Q. Deterioration-associated microbiome of stone monuments: Structure, variation, and assembly. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02680-17.

- Rao, H.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Wang, C. Proteomic identification of organic additives in the mortars of ancient Chinese wooden buildings. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 143–149.

- Theodoridou, M.; Török, A. In situ investigation of stone heritage sites for conservation purposes: A case study of the Székesfehérvár Ruin Garden in Hungary. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2019, 6, 15.

- Gulotta, D.; Toniolo, L. Conservation of the Built Heritage: Pilot Site Approach to Design a Sustainable Process. Heritage 2019, 2, 52.

- Chelazzi, D.; Poggi, G.; Jaidar, Y.; Toccafondi, N.; Giorgi, R.; Baglioni, P. Hydroxide nanoparticles for cultural heritage: Consolidation and protection of wall paintings and carbonate materials. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 392, 42–49.

- Becerra, J.; Mateo, M.; Ortiz, P.; Nicolas, G.; Zadarenko, A.P. Evaluation of the applicability of nano-biocide treatments on limestones used in cultural heritage. Herit. J. C Herit. 2019, 38, 126–135.

- Cioffi, N.; Torsi, L.; Ditaranto, N.; Tantillo, G.; Ghibelli, L.; Sabbatini, L.; Bleve-Zacheo, T.; DAlessio, M.; Zambonin, P.G.; Traversa, E. Copper nanoparticle/polymer composites with antifungal and bacteriostatic properties. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 5255–5262.

- Fernandes, P. Applied microbiology and biotechnology in the conservation of stone cultural heritage materials. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 73, 291–296.

- Romano, I.; Abbate, M.; Poli, A.; D’Orazio, L. Bio-cleaning of nitrate salt efflorescence on stone samples using extremophilic bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1668.

- Marin, E.; Vaccaro, C.; Leis, M. Biotechnology applied to historic stoneworks conservation: Testing the potential harmfulness of two biological biocides. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2016, 7, 227–238.

More

Information

Subjects:

Architecture And Design

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.8K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

10 Aug 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No