| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Esperanza Gomez-Lucia | -- | 9151 | 2023-08-03 21:10:28 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | -17 word(s) | 9134 | 2023-09-05 11:57:32 | | |

Video Upload Options

Avian leukosis viruses (ALVs) have been virtually eradicated from commercial poultry. However, some niches remain as pockets from which this group of viruses may reemerge and induce economic losses. Such is the case of fancy, hobby, backyard chickens and indigenous or native breeds, which are not as strictly inspected as commercial poultry and which have been found to harbor ALVs. In addition, relics of ancient infections by ALV remain in the genome of birds, with which ALV may recombine and generate new viruses.

1. Introduction

1.1. Avian Sarcoma/Leukosis Virus (ASLV) in the Past and in the Present

1.1.1. ASLV in History

1.1.2. Current Relevance of ALV

2. Transmission of ALV

2.1. Routes of Transmission: Horizontal Versus Vertical

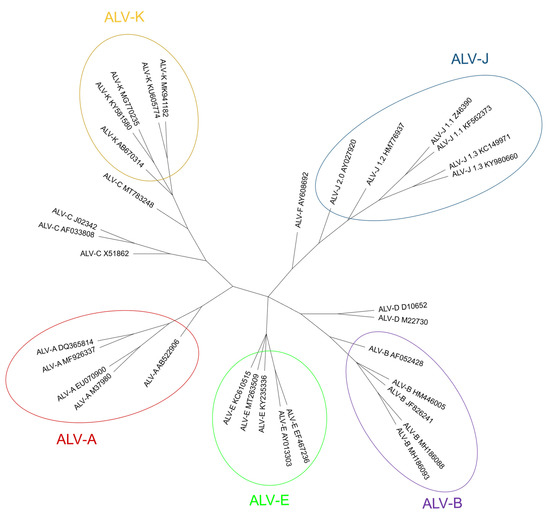

2.2. ALV Classification into Subgroups

| Alv Subgroup | En/ex 1 | Cytophaticity | Recombination 2 | Cell Receptor | Hosts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALV-A | EX | NO | ALV-J | Tva protein | Galliformes (Gallus gallus; Meleagris gallopavo; Pavo muticus) Anseriformes (Sibirionetta formosa; Anas carolinensis) |

| ALV-B | EX | YES | ALV-J ALV-E |

Tvb protein | Galliformes (Gallus gallus; Meleagris gallopavo) Anseriformes (Sibirionetta formosa; Anas carolinensis) |

| ALV-C | EX | NO | ALV-J | Tvc protein | Galliformes (Meleagris gallopavo) |

| ALV-D | EX | YES | Tvb protein | Galliformes (Meleagris gallopavo) | |

| ALV-E | EN | - | ALV-A ALV-B ALV-C ALV-J |

Tvb protein | Galliformes (Gallus gallus; G. sonneratii (EAV-HP); Meleagris gallopavo; Lophortyx gambelii, Pavo muticus) Anseriformes (Anas falcata; A. carolinensis; Sibirionetta formosa) |

| ALV-F | EN | Galliformes (Phasianus colchicus; P. versicolor; Chrysolophus pictus) | |||

| ALV-G | EN | Galliformes (Chrysolophus pictus) | |||

| ALV-H | EX | Galliformes (Perdix perdix) | |||

| ALV-I | EX | Galliformes (Callipepla gambelii) | |||

| ALV-J | EX | ALV-A ALV-B ALV-C |

chNHE1 | Galliformes (Gallus gallus; Meleagris gallopavo; Perdix perdix) Anseriformes (Anas acuta; A. poecilorhyncha; A. penelope; A. carolinensis; A. crecca; A. clypeata; A. formosa; Sibirionetta formosa; Mareca strepera) Passeriformes (Tarsiger cyanurus; Emberiza elegans; Phylloscopus inornatus; Poecile palustris) |

|

| ALV-K | EX | ALV-E | Tva protein | Galliformes (Chinese indigenous chickens: Gallus gallus) |

2.2.1. Exogenous ALV Subgroups

2.2.2. Endogenous ALV Subgroup

3. The Avian Leukosis Virus, Its Characteristics and Properties

ALV, along with RSV and other similar viruses, is a member of the Retroviridae family, belonging to the Alpharetrovirus genus. ALV virions are enveloped and have a 35–45 nm in diameter capsid which has C-type morphology. The total size of the virion is between 80 and 120 nm [88][89]. They are enveloped viruses which exhibit glycoproteic spikes inserted in the envelope, which has a rounded (knobbed) shape [5].

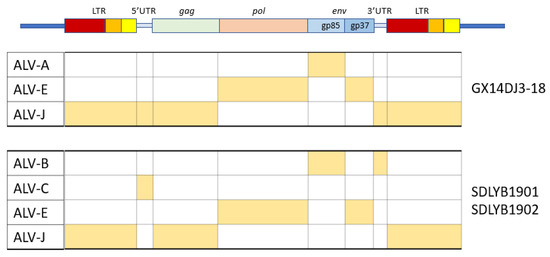

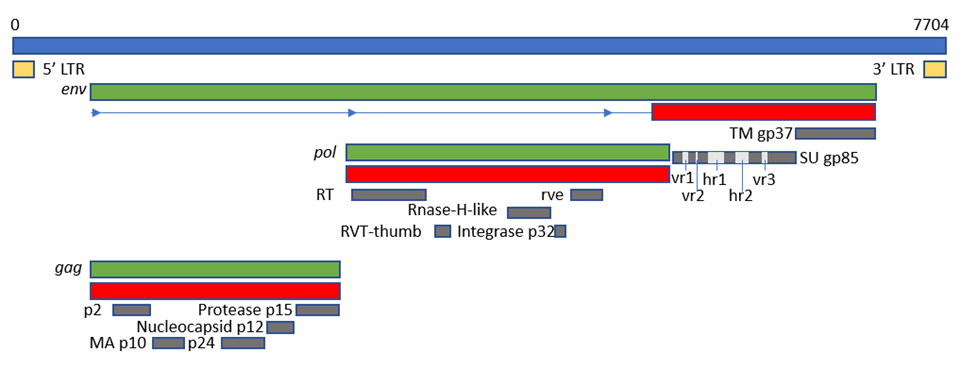

3.1. The ALV Genome

The viral genome is around 7.2–7.8 kb in size and has an organization consisting of gag-pro-pol-env (Figure 3), which is standard for simple retroviruses. The gene gag-pro encodes the inner proteins, including the capsid protein, p27(CA), an antigen common to all subgroups of ALV [20] as well as the matrix protein (MA), p10, nucleocapsid protein (NC), and the protease (PRO). As in other retroviruses, pol encodes the proteins necessary for viral replication [5].

Gene env (envelope) encodes the surface (SU, gp85) and transmembrane (TM, gp37) proteins, which are cleaved from the Env precursor trimer during maturation. gp85 (SU) binds to the cell receptor in a two-step process with intermediate structures. This unusual mechanism has allowed characterization of the binding steps [38]. gp37 (TM), a transmembrane glycoprotein, anchors gp85 (SU) to the viral envelope and has fusogenic properties, being responsible for the development of syncytia in infected cells. Env is highly determinant of the type of tumors chickens will develop, either lymphoid or erythroid [90]. The receptor specificity of gp85 (SU) permits the classification of ALVs into the subgroups mentioned above according to the sequence of two hypervariable regions, host range region (hr)1 and hr2, and three less variable regions, variable region (vr)1, vr2 and vr3 (Fig. 5). It is highly immunogenic and determines the production of neutralizing antibodies. ALV from the different subgroups tend not to cross-neutralize, except for partial cross-neutralization between subgroups B and D [91][92]. A variety of studies have identified hr1 (aa194–198 and aa206-216) and hr2 (aa251–256 and aa269–280) as the main binding domains between the viral gp85 (SU) and the host protein receptor [58][93], with vr3 contributing to the specificity of the receptor interaction for initiating efficient infection [94]. Thus, polymorphisms in hr1 and hr2 regions may determine susceptibility due to increased or decreased binding capability, with the possibility that different or new subgroups of the virus arise if the hr regions bind to a different chicken cell surface protein [21]. Since the variability of hr regions in circulating ALVs establishes cell receptor binding, this knowledge may be useful for determining cell receptor edition or selection strategies.

Figure 3. Schematic representation of the genome of ALV KU375453 (ALV-A), adapted from the GenBank graphics feature. Blue box represents the complete genome and its length in base pairs (bp); green boxes represent ORFs; red boxes represent polyproteins; grey boxes represent mature proteins; cream boxes represent the LTRs. The position of hr1, hr2, vr1, vr2 and vr3 is adapted from [95].

3.2. The Importance of the Long Terminal Repeats (LTRs)

The proviral genome (DNA genome integrated in the host chromosome) is flanked by identical sequences known as the Long Terminal Repeats (LTR), which have three functionally different regions which, from upstream to downstream, are: U3 (contains enhancer elements and the promoter), R (start of transcription) and U5 (with post-translation regulatory elements and a role in polyadenylation) [96][97] and a direct ribosome binding site (IRES), which enables cap-independent translation [98]. As in other retroviruses, U3 in the 5′ LTR is the controlling element of transcription because it contains transcription binding sites (TBS) which react to cellular signals enhancing transcription [99][100]. Some of them are AP-1, c-ets, STAT5, NF-1, or a glucocorticoid receptor. With the exception of AP-1, which is only present in ALV-E, the rest are equally present in other sequences studied. A large number of C/EBP predicted binding sites are detected in the U3 of both ALV-A and ALV-E GenBank sequences [101]. Most of the TBS are involved in the response to interferon (IFN)-α/β, IFN-γ, interleukins (IL), toll-like receptors (TLR) and other pattern recognition receptors (PRR), or are involved in cell proliferation or inflammation [102][103][104][105][106][107]. Interestingly, LTRs from endogenous ALV-E proviruses in the chicken genome have a very different sequence motif when compared with exogenous subgroups LTR sequences, resulting in different TBS which probably affect the response to cell factors [101]. Contrasting with U3′s high variability, U5 is mostly conserved among all ALV subgroups [101].

3.3. ALV Infection of the Cell

The development of tumors in slow transforming ALVs greatly depends on the integration of the provirus in the vicinity of cellular genes involved in cell growth and differentiation. ALV has a preference for integrating near expressed or spliced genes, at least in cultured cells [108] but, in most cases, integration can be described as random and unpredictable. Because it is random, the provirus is often inserted near a cellular locus, directing its expression. ALV oncogenesis starts when an oncogene like c-myc, blym-1 or c-bic are upregulated by the potent enhancer elements in the 5′ LTR [5]. This is termed as insertional oncogenesis [15][109].

Thus, the integration site determines the progression of the disease. This is the case of the clonal progression of B-cell lymphomas in chickens infected by ALV [108][110]. The MET gene is a common integration place in hemangiomas induced by ALV-J [111]. This gene encodes a well-studied receptor of tyrosine kinase that binds hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) and plays important roles in normal development and in a wide range of human cancers [111]. In an individual ALV tumor, between 700 and 3000 novel integration sites can be observed, with an average of 2.4 to 4 successful integrations per cell [108] and a maximum of 20 integrations reported in a single cell [5].

4. Presence of ALV in Species other than Chickens

4.1. Host range

Chickens are the natural hosts for all viruses of the leukosis/sarcoma group. However, other natural hosts may also exist, but chickens are the species studied the most due to the consequences of ALV-infection in chicken production. Experimentally, some ALV subgroups have a wide host range and can be adapted to infect unusual hosts by passage in very young animals. ALV-J seems to have the widest host range, probably owing to its receptor usage (see below). There are many studies of seroprevalence and/or the presence of ALV-A, ALV-B and mainly ALV-J in several wild and domestic bird species other than chickens, which are not necessarily related to clinical disease. A better estimation of the host range of ALV, especially of the emerging ALV-J, is important to better understand the role that other birds may play in ALV epidemiology, transmission to other birds and spread to new regions. For example, the presence of ALV-J in Anseriformes and other migratory birds highlights the potential role of wild-bird migration in the spread of ALV-J worldwide [112]. The incidence and relevance of the infection is different in birds in general and chickens specifically raised in commercial and non-commercial flocks.

4.2. ALV Prevalence in Broilers and Layer Poultry (Commercial Poultry)

Infection by ALV-A/B/C/D has been practically eliminated from breeding flocks of most international breeding companies (broilers and layers producers), mainly in major developed countries and regions like the United States and Europe, due to strict eradication programs and management measures (reviewed in [20]). In addition, several countries, including China, Australia and Iran, have developed their own eradication programs (reviewed in [54]). However, the spread of ALV remains a major concern worldwide, and is even emerging in different areas, such as in China. The emergence of ALV-J in China may be also related to the difficulty in implementing eradication programs, the carrying out of which is problematic on small-scale farms (yellow-chicken local breeds) because of the lack of financial or technical support [21][22].

ALV-J was first isolated from broiler breeder chickens in the UK in 1988 and in the early 90s in the United States and Japan. It has rapidly spread around the world, causing severe economic losses to the poultry industry in several countries and regions such as Europe, East Asia (China, Malaysia, Taiwan), Russia, Australia, Israel and Egypt [22][46][113][114]. In recent years, the host range of ALV-J infection has expanded [46][115] from broilers to laying hens, local native chicken breeds [4][19][113] and gamecocks [22]. Its geographical spread, increased pathogenicity and faster transmission ability explain why it is the most prevalent subgroup nowadays [1][46][49][116]. For example, in China, one of the countries most affected by ALV, the most prevalent nowadays is ALV-J, followed by subgroups ALV-A and ALV-B, while subgroups ALV-C and ALV-D are seldom reported [21]. A survey in Russia showed that 70% of 223 production sites from 46 regions were seropositive to ALV-J, and that 90% were seropositive for generic ALV [54].

ALV-K was first isolated from a Chinese native indigenous chicken breed, “Luhua”, in 2012 [21][57]. Shortly afterward, several ALV-K strains from other yellow-feather broilers and Chinese indigenous or native chicken breeds in South China were described [42][59][117]. It is believed that ALV-K has existed in the indigenous chicken breeds of East Asia for a long time. Subsequent epidemiological investigation revealed that ALV-K was widespread among Chinese native chickens [42]. Most ALV-K were isolated from apparently healthy individuals, but some variants are significantly pathogenic [54][58][59][118][119].

4.3. ALV Prevalence in Backyard, Fancy and Hobby Chickens (Non-Commercial Poultry)

The rearing of small poultry flocks in backyards for eggs and meat, even sometimes kept as ‘pets’ in private gardens in cities, has gained popularity in western countries. These backyard poultry flocks consist mostly of native layer hen breeds, but also include fancy chickens and other domestic gallinaceous birds, such as turkeys, quails and geese, that are often obtained from various sources. The biosecurity measures of these non-commercial flocks are much lower than in bigger poultry farms, and they potentially may represent a risk in the transmission of viruses to other wild or domestic birds [20][120][121][122] and there is little knowledge of the diseases that these chickens could be at risk of contracting. In addition, strategic programs for the control of ALV infections have not yet been implemented in these type of flocks [20].

Data on the presence of ALV in backyard or in fancy chickens are very scarce and are often derived from questionnaires and post-mortem examinations (such as the myxosarcoma associated with ALV-A infection reported in a flock of mixed fancy breed chickens in USA in 2010 [123]), so its prevalence could be underestimated. ALV-induced leukosis/sarcoma diseases were presumptively diagnosed in 3–4% of birds in backyard poultries in USA [124][125], but no suspected cases were reported in a study in Finland [121].

One study on pure-fancy chickens in Germany using ELISA detected the presence of p27 (CA) in cloacal swabs in 28.7% of individuals and 56.0% of the 50 flocks tested [20], higher than the prevalence of antibodies previously reported in Switzerland in 2002 (2–4%) [126] and in the Netherlands in 2004 [127]. ALV-K was the subgroup identified in fancy chickens in Germany which also differs from the detection of ALV-A, B, and J identified in the Netherlands [127]. Therefore, the high proportion of fecal shedders suggests that fancy chickens should be considered a potential reservoir for ALV. High priority should be given to biosecurity by poultry farmers and veterinarians to prevent the introduction of the virus on commercial poultry farms, especially because of the recent increase in free-range management in commercial egg and poultry meat production [126].

In 2018, an ALV-J associated myelocytoma was described in a hobby chicken in the UK, a 12-month-old Black Rock chicken from a mixed breed flock of 6 birds. This chicken had respiratory and paralysis signs, and tumor lesions were observed in several organs that tested positive for p27 (CA) by ELISA and positive to ALV-J by PCR [122]. This was the first time that ALV-J had been detected in the UK since its eradication in the 1990s, which suggests that ALV-J may be circulating at a low level in backyard chickens, thus representing a possible reservoir of infection for other birds.

Besides domestic fowl, host-range studies showed that red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) and Sonnerat’s junglefowl (Gallus sonneratti) are susceptible to infection by ALV-J (HPRS-103). These findings highlight the importance of continued surveillance of backyard, fancy and hobby chickens to detect potential new and re-emerging disease threats, such as ALVJ and ALV-K, which may be of significance to the wider poultry population [122].

4.4. ALV Prevalence in Non-Chicken Species

There have been many studies looking for potential new hosts for ALV in different types of birds: domestic (turkeys, quails), urban (pigeons) and different captive and wild bird species, including passerines, columbids, waterfowl, and psittacines [120]. While ring-necked pheasant, Japanese green pheasant, golden pheasant, Japanese quail, guineafowl, Peking duck, Muscovy duck and goose are considered to be resistant to exogenous ALV [128], it has been known for some time that RSV can cause tumors in pigeons, pheasants, ducks, turkeys, rock partridges (Alectoris graeca) depending on the RSV subgroup/pseudotype. There are also several studies that demonstrate the susceptibility to ALV infection in vitro of cells derived from different species of birds, such as quail cells [129], related to the presence of a compatible receptor (Section 5), making it feasible that ALVs infect these species. This has brought concerns of transspecies ALV transmission, mainly ALV-J due to its higher transmissibility and broader range of hosts. The transmission to new species could establish natural reservoirs of circulating ALVs, not subjected to surveillance and control, and what is crucial, with a capability for further evolution [130]. This may represent also a challenge for the ecological balance [131]. The presence of the virus has been detected in different captive and wildlife birds in numerous countries, mainly in China and East Asia. This a priori means that these birds would be susceptible to infection in vivo, and perhaps play an epidemiological role in their transmission, carrying and spreading the virus to other birds.

Turkeys are important domestic bird species that are reared on a large scale in many countries. Turkey cells are susceptible to ALV exogenous subgroups, although some show resistance to ALV-B, D, and J [116][132]. In 2017, Zeghdoudi et al. [133] reported an outbreak of tumor disease in turkey flocks in Eastern Algeria, with a mortality rate of 10% in animals aged 17 weeks and older. Tumors tested positive to the ALV p27 (CA) antigen by ELISA. Venugopal et al. [132] showed that 1-day-old turkey poults are experimentally susceptible to infection with ALV-J strain 996, a myc-expressing, acutely-transforming recombinant, that induces tumors with histopathological lesions of myelocytomatosis between 3 and 4 weeks after infection. In the same study, the authors also reported that ALVJ could spread among turkeys by contact, although at low levels, which stresses the importance of segregating turkey- and chicken-breeding operations to avoid the spread of ALV-J infection. This would be especially relevant in familiar small farms and backyards.

Quails are very popular gamebirds that are raised in game farms for hunting purposes or other uses together with other gamebird species such as pheasants and partridges. ALV-A has been detected in quails in China [134], and there are several reports on the ALV receptors and the susceptibility of quails to ALV-A and ALV-J experimental infections [130][131][135]. Zhang et al. [131] reported that adult quails were less susceptible than chickens to experimental infection by ALV-A because only a few infected birds showed transient viraemia, low cloacal virus shedding and antibody response, which might limit their role in bird–to–bird transmission. New world quails are known to be susceptible to ALV-J infection because they have a receptor compatible with virus entry [130].

Partridges, closely related to pheasants and grouse, have been previously described as ALV-J resistant [128]. However, Shen et al. [136] concluded that the grey partridge (Perdix perdix) may develop ALV-J-linked tumors when bred together with infected susceptible species, such as black-bone silky fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus Brisson), effectively showing that housing different avian species together provides more opportunities for ALV-J to evolve rapidly and expand its host range [136].

The presence of ALV-A, ALV-B, and/or ALV-J has been reported in wild ducks from the order Anseriformes and some species of small Passeriformes in China [112][137][138]. ALV-J has been detected in wild ducks, though Zeng et al. [139] could not determine whether ducks are susceptible to ALV-J infection or simply carriers of it following contact with domestic poultry harboring very high loads of virus, as they could not perform serology. However, it would not be surprising to find that wild ducks are truly susceptible to ALV-J, as poultry and wild ducks are evolutionarily more closely related than poultry and passerine birds, and wild ducks tend to carry and spread poultry pathogens easily [138]. Later findings by Reinišová et al. [140] confirmed that certain Asian ALV-J strains had coevolved and gained the capability to enter duck cells. Surprisingly, the sequencing of ALV-J strains from passerines showed their similarity in the 3’UTR to those found in Chinese layer chicken isolates, indicating that both may have a common origin, which points to the possibility of a convergent relationship that needs further investigation [138].

Pigeons are reared in many countries, as well as being very common urban birds in cities worldwide. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one study by Zhang et al. [131] describing the absence of viremia, cloacal virus shedding, antibody responses, clinical signs or pathological lesions in experimentally ALV-A-infected adult pigeons. These results suggest that pigeons are resistant to ALV-A infection, although the susceptibility to ALV-J has not been studied. Natural infection by ALV-A through E has been reported in other birds, including two green peafowl (Pavo muticus) with neoplasia [141] and in wild ostriches from a farm in Zimbabwe, which tested positive for antibodies and at least one case had clinical illness [142].

All these facts raise questions about the presence of ALV in wild birds other than chickens and close relatives, but few such studies exist. In conclusion, the ALV host range is broader than just the Galliformes; but further research is needed to determine which avian species are susceptible.

4.5. Endogenous ALVs in Non-Chicken Species

Non-chicken species may be infected both by ALV-E and by other endogenous retroviruses. Host range experiments show that although jungle fowl, Peking duck and goose cells are resistant to ALV-E, this subgroup may infect pheasant, Japanese quail, Guinea fowl and turkey cells in vitro [5].

ALV and related viruses have infected the germinal line of Galliformes at several points in time [143]. Subgroups F, G, H and I, sometimes described as endogenous ALVs, were also considered ALV but research at the time [144] found big differences between them and the canonical ALVs in hybridization studies. Since then, few research efforts have been made on subgroups F to I and a lack of a complete model sequence in databases prevents further advance, as mentioned above. Nonetheless, they are still considered ALVs.

ALV-F was first described in ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) in 1973 [145]. A year later, ALV-G was found in golden pheasant (Chrysolophus pictus) and was recognized as different from ALV-F [146]. ALV-H and ALV-I were found in Hungarian partridge (Perdix perdix) and Gambel’s quail (Callipepla gambelli) endogenous sequences respectively [147]. Dimcheff et al. [148] reported that gag regions similar to those of ALV exist in the genome of a wide range of 26 different Galliformes species such as grey partridge (Perdix perdix), black grouse (Lyrurus tetrix) or helmeted guineafowl (Numida meleagris) and even drafted the complete sequence of TERV (Tetraonine endogenous retrovirus), an ASLV from the ruffed grouse, Bonasa umbelus [149] but could not determine whether they were of exogenous or endogenous nature, due to the high conservation of gag sequences. Though Zhu et al. described the detection of ALV gag gene in the genomic DNA of eight Chinese native domestic goose (Anser anser domesticus) [150], these results were later refuted by Elleder and Hejnar, as it is possible that PCR amplifications were contaminated with chicken genomic DNA [151]. According to Dimcheff et al. [149], endogenous ALV is restricted to Galliformes and is not present in the closely related Anseriformes order or the families Cracidae and Megapodiidae. However, later research by Hao et al. [152] found proviral ALV-E in wild duck samples [155], increasing the range of species where ALV proviruses are present. Researchers have found ALV env sequences in genomic scaffolds from Alectoris rufa genome that was recently published (UCSC genome browser Id: GCA_947331505.1; unpublished results) and also in Tympanuchus and Lagopus (both of the family Phasianidae) published RNA sequences (GenBank Accession Numbers XM052699038 and XM042864983, respectively). Presence of endogenous ALV in Tympanuchus and Lagopus was also reported by Dimcheff et al. [148] and for a different species of Alectoris by Frisby et al. in 1979 [153].

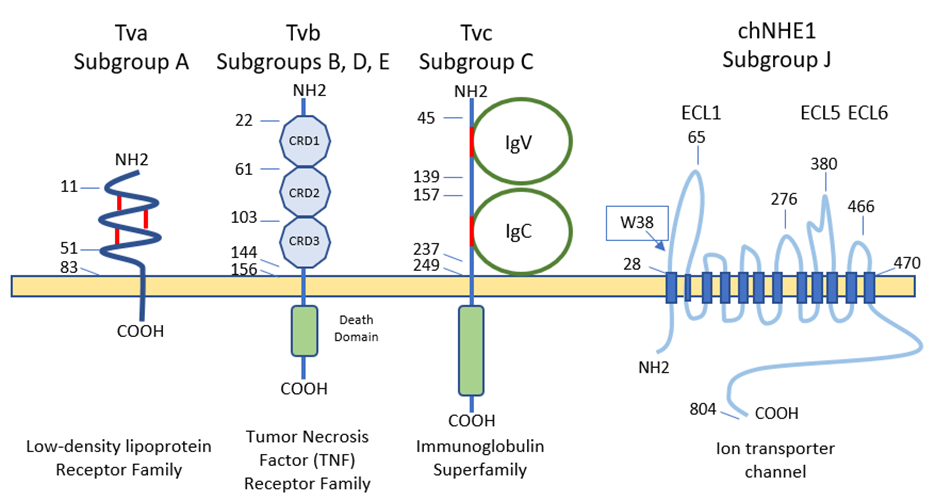

5. Cell Receptors for the Different ALV Subgroups

ALV enters susceptible cell types by binding to specific receptors [21][33] (Figure 4). The differential susceptibilities of various cell lines of chickens to infection led to the definition of three distinct autosomal recessive genes that were predicted to encode cellular receptors for different viral subgroups, as well as to the concept of viral interference [154].

ALV-A enters the cell through the Tva protein, which is homologous to a low-density lipoprotein receptor in humans [5][21][33]. However, ALV-A may broaden its receptor usage to other receptors in the presence of a competitor of Tva, SUA-rIgG immunoadhesin [155]. Tva is also the receptor for ALV-K [156]. The viral interaction domain of Tva is determined by a 40-aa-long motif which interacts with key amino acid sites, modulating the affinity, and variations in these aa result in a weaker replication ability of ALV-K than ALV-A [58][137][157].

The gp85 (SU) glycoproteins of ALV-B/D/E bind to the three extracellular cysteine-rich domains (CRD) of Tvb receptors, which belong to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family (TNFR). Mutations in these domains modulate the susceptibility to the mentioned ALV subgroups [21] and it has been proposed to generate resistance to ALV [158]. As in other retroviruses, modifications in the sequence of gp85 (SU) also result in decreased susceptibility to infection by these three subgroups. The normal cellular function of chicken Tvb remains unclear, though it may be similar to the other members of the TNFR family. Besides the CRDs, Tvb also has a cytoplasmic death domain that can activate cell apoptosis through the caspase pathway and produce a cytopathic effect [5][159].

ALV-C binds to Tvc, a member of the butyrophilin family of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Tvc extracellular tail contains two immunoglobulin globular domains, IgV and IgC. The gp85 (SU) of ALV-C binds to IgV which has two aromatic aa residues (Trp-48 and Tyr-105) which are key determinants of receptor-virus interactions. In addition, a domain such as IgC seems to be necessary as a spacer between the IgV domain and the transmembrane domain for efficient Tvc receptor activity, most likely to orient the IgV domain a proper distance from the cell membrane [160].

Subgroup ALV-J uses the 12-span transmembrane Na+/H+ channel protein type 1 (chNHE1) as cell receptor [5][33][161], sometimes referred to as Tvj. NHE1 is a housekeeping protein that regulates intracellular pH, Na+ and H+ ion transport, and cell proliferation; it is expressed on almost all cell membranes [162] and chicken breeds, possibly rendering all chickens susceptible to ALV-J [47]. The observation of virus budding from nearly all tissues and cell types with the exception of neurons and germinal cells confirms that the receptors are present in most cells. It has been reported that the expression of mRNA and protein of NHE1 can be induced by ALV-J, and chickens infected by ALV-J develop a more complex array of clinical signs, probably due to the relevance of the receptor in cell biology, as the abnormal expression of NHE1 can cause intracellular pH imbalance, inhibit cell apoptosis, promote cell proliferation, and lead to tumorigenesis [14]. This may be the reason why chickens easily develop tumors in bone marrow, liver, and kidneys after infection with ALV-J. It has been reported that the deletion or substitution of tryptophan in position 38 (W38) increases resistance to ALV-J [5][163]. Besides chNHE1, chicken annexin A2 (chANXA2) [164] and the chicken glucose-regulation protein 78 (chGRP78) [21] have been described recently as receptors for ALV-J, possibly as secondary receptors in the absence of chNHE1.

Figure 4. Schematic representations and residue position of critical domains of the four families of cellular surface proteins used ALV receptors (adapted from [31] and [144]). CRD, cysteine-rich domains. IgV, immunoglobulin variable domain. IgC, immunoglobulin constant domain. ECL, extracellular loop. The position of tryptophan-38 (W38) is shown in the ECL1 of chNHE1.

6. Immune Response against ALV Infection

Immune responses to ALV are complex and not fully understood, and many questions remain unsolved. In addition, ALV, specially ALV-J, are well known immunosuppressive viruses and can suppress innate and adaptive immune responses [33][165], affecting the monocyte, macrophages, dendritic cells (DC), B- and T-cell functions. In recent years much more attention has been paid to the innate immune responses and how ALV can evade them.

6.1. Innate Immunity

Host immune response against ALV is initiated with the recognition of the virus by the innate cells. It was reported that the viral RNA of ALV could be recognized by TLR7 and MDA5 (melanoma differentiation–association gene 5, a member of the RIG-I-like helicase receptors (RLRs) family), inducing the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) and inflammatory cytokines [166]. However, data of other innate sensors and mechanisms of cellular innate immunity are quite limited [167][168].

A well-known mechanism of the cellular innate defense against retroviruses in mammals is the Host Restriction Factors (RFs), antiviral molecules that inhibit the retroviral replication cycle at multiple steps, and that are often up-regulated by type I interferons. Few RFs have been identified in chickens that are able to restrict ALV replication: the cellular scaffolding protein Daxx promotes the epigenetic silencing of integrated proviruses [169]; CCCH-type zinc finger antiviral protein (ZAP) inhibits ALV-J replication by interaction with mRNA and SU protein [170]; TRIM62 restricts ALV-J replication through the SPRY structural domain [171]; TRIM25 inhibits ALV-A replication by regulating MDA5 [172]; cholesterol 25-hydroxylase (CH25H) probably inhibits viral entry through a not completely understood mechanism [173]; and a recently identified tetherin/BST-2 protein blocks the release of newly formed viral particles by linking them to the membrane of infected cells [174]. One of the most widely studied RFs, apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme-catalytic polypeptide-like 3 (APOBEC3), is not present in birds. A better knowledge of the avian RFs could be also very interesting because they are key determinants of cross-species transmission, as has been demonstrated in mammal retroviruses. In addition, understanding the mechanisms of RFs interaction with ALV may be used to develop novel antiviral strategies in poultry [170].

The role that non-coding RNAs play in the host innate response to ALV has received much attention in recent years. Host microRNAs (miRNAs) interfere with cell growth, proliferation and apoptosis and their aberrant expression may be associated with neoplastic diseases; but they are also involved in the regulation of the host innate response. Several miRNAs, such as miR-34b-5p and miR-23b, were significantly increased in the spleen of ALV-J-infected chickens (reviewed in [168]). miR-34b-5p inhibited the expression and activation of MDA5, facilitating ALV-J replication [175]. miR-23b could decrease the expression of interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-1 and further down-regulate the expression of β-interferon (IFN-β), which facilitated ALV-J replication [176]. On the contrary, in ALV-J infected cells the expression of miR-125b was down-regulated and apoptosis inhibited [177]. These data suggest that ALV could regulate in some way the expression of host miRNAs to target host proteins, inhibiting host anti-viral response. However, more efforts are needed to elucidate this mechanism of innate immune evasion by ALV [168].

Monocytes, macrophages and DCs are the pivotal innate cells against viral infection and there are several studies about the effect of ALV infection, mainly ALV-J, on this cell lineage. ALV-J infection of monocytes induces cell death, but the underlying mechanism is still unclear although there is an increase in the activities of caspase 1 and 3 and upregulation of IL-1β and IL-18. Therefore, infected monocytes cannot differentiate to macrophages, altering the innate and adaptative immune response [178]. Previous studies by Gazzolo et al. [179] showed that ALV-B/C (but not ALV-A/D) viruses could persist in macrophages from peripheral blood up to 3 years, in 1- or 2-month-old chickens immunized against these viruses. The monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) infected with ALV-J secrete more IFN-β and pro-inflammatory IL-1 and IL-6, and less anti-inflammatory IL-10, which might suggest that this is a strategy for ALV-J to evade host innate immunity and even establish latent infections in macrophages and serve as cellular reservoirs [167]. In addition, IL-1 and IL-6 have been linked to tumorigenesis, which suggests that inflammation would be associated with tumor development [180]. Other studies described the inhibition of type I IFN, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12 production in infected ALV chicken macrophages. These discrepancies observed in different studies may be related to the use of macrophage cell lines, instead of MDM, in which immune functions can be impaired and genetic differences may have developed with continuous subculture [180]. As in monocytes, ALV-J are able to infect chicken DCs and disturb their normal functions, including their rate of maturation, while inducing apoptosis and causing aberrant expression of microRNAs [181]. ALV-J also decreases the expression of TLR1, 2, and 3 and of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) classes I and II [182], and alters cytokine expression. All this causes aberrant antigen presentation and an altered immune response. These alterations in DC and monocyte/macrophage functions may be involved in the immunosuppression of the host innate immune response during ALV-J infection [181].

What are the subcellular mechanisms underlying ALV interference with the host innate immune response? Although they are not fully known, it appears that the virus tarets host proteins involved in signaling pathways of the innate immune response. Some studies have reported that ALV infection can, among others, (a) up-regulate the expression of SOCS3, thus inhibiting the phosphorylation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway [183], (b) block phosphorylation of IκB, avoiding the dissociation of the complex with NF-κB, which does not translocate into the nucleus to activate immunoregulatory genes [184], and (c) up-regulate the disruptor of telomeric silencing 1-like protein (DOT1L), inhibiting the expression of MDA5 (which is a cytosolic double-strand RNA sensor), thus affecting the recognition of ALV RNA by host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [185]. As a result in all cases, the activation of the type I interferon signal transduction pathway is impaired [168][172]. On the other hand, miRNAs and other small RNA molecules (piRNA and lncRNA) and proteins derived from endogenous ALV can sense or modulate immune responses against viruses [21]. As mentioned above, despite the evidence for innate immunosuppression caused by ALV, there are still many unresolved questions to understand the underlying mechanisms by which ALV inhibits the host’s immune response.

6.2. Humoral Immune Response: The Role of Antibodies

The humoral immune response to ALV mainly depends on the timing of infection (congenital vs. horizontal), the type of viral subgroup involved and the genetic basis of resistance of the chicken. After horizontal transmission, most of the chickens infected by ALV subgroups A and B (unlike those infected by ALV-J) develop a transient viremia within a week, followed by neutralizing antibodies at three weeks or later directed against the envelope proteins that rise to a high titer and have a lifelong persistence, preventing the reappearance of viremia [186]. These neutralizing antibodies reduce the amount of virus in the body, which in turn will limit tumorigenesis, but they generally are considered to have no or an undetectable direct influence on tumor growth [187]. In addition, neutralizing antibodies enhance virus evolution in order to escape their blockage. The fact that in ALV-J-infected chickens levels of viremia do not correlate with the presence or absence of neutralizing antibodies is associated with the development of escape variants [188][189]. The presence of maternal antibodies against ALV-A in chickens hampers the development of neutralizing antibodies by the chick, allowing viremia and virus shedding [186].

Congenital and early infections (<2 weeks of age) cause immunological tolerance with no humoral response to the virus, and infected chickens develop a persistent viremia in the absence of neutralizing antibodies [190][191]. In particular, ALV-J induces a severe and persistent immunotolerance in congenital infection through mechanisms which are not completely elucidated. This immunotolerance is characterized by persistent viremia, dysplasia of lymphoid organs and severe decrease in the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T-cells in blood and lymphoid organs, CD3+ T-cells and B-cells in the spleen [192]. The bursa of Fabricius is poorly developed and its structure does not differentiate into cortex and medulla (this is not the case in post-hatch infection, in which the bursa development is relatively normal [193]) due to the blocking of the differentiation of B-cell progenitors, causing an arrest of the development of B-cells and the inhibition of humoral immunity; in addition, ALV-J gp85 (SU) mediates B-cell anergy by inhibiting BCR signal transduction [193]. Congenital ALV-J infection also induces the production of activated CD4+CD25+ Tregs that inhibit B-cell functions maintaining the persistent immunotolerance [192].

Depending on the humoral immune response and the presence of a detectable virus in the blood, susceptible and infected ALV chickens can be classified in several conventional categories: viremia with (V+A+) or without (V+A-) neutralizing antibodies, and no viremia with neutralizing antibodies (V−A+) [15][194][195]. Most of the infected chickens are V-A+. Less than 10% are V+A- (immunotolerant chicken, infected congenitally or at a very young age) and transmit the virus to other birds and to their progeny, and are likely to develop lymphoid or myeloid leukosis (reviewed in [1][5]); this may not be the case in ALV-J infected chicken. V+A+ are usually those in the process of clearing an acute infection, eventually becoming V−A+ [15]. However, the plasticity of ALV-J and its capability of generating escape mutants is readily appreciated through sequencing the consecutive ALV-J isolates from V+A+ chickens, which show evolution, thereby contributing to viral persistence [189]. Genetically resistant birds in a susceptible flock and those in an infection-free flock are V-A-.

6.3. Cellular Immune Response: The Role of T-Cell Dependent Cytotoxicity

Initial studies showed that cytotoxicity by T-cells seemed to play a role in the susceptibility or resistance of the various MHC-I haplotype chicken lines to ALV-A infection [196]. A role for cellular immunity was also correlated with immunosuppression of the T-cell function in ALV-A infected chickens [197].

Once again, most of the evidence for the involvement of the cellular immune response in ALV infections comes from studies with ALV-J. In experimental infections with ALV-J, CD8+ T-cell response was detectable by 7 days post infection (dpi), while specific antibodies were detected from 14–21 dpi in some chickens. As viremia levels decrease from 14 dpi, and are generally negligible by 21 dpi, it is evident that humoral response is not solely responsible for viral clearance [198]. Dai et al. [198] also reported that viremia of four experimentally infected ALV-J chickens could be eliminated without antibody production, which suggests that CD8+ T-cell response was the potential key factor to defend against ALV-J infection. This was supported by the detection of an increased percentage of CD8+ T-cells of phenotype CD8αβ (CTLs) in the thymus and peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) at 7 and 21 dpi, and an up-regulated expression of two antiviral ISGs (Mx1 and IFIT5) and the cytotoxicity-associated genes granzyme K, NK lysin and IFN-γ, linked with the stage of activation of the CTLs and the clearing of viruses. However, Dai et al. [198] also detected a decrease in the CD4+/CD8+ ratio in the thymus at 14 dpi and in the PBL at 21 dpi, which implied that the virus may have exerted an immunosuppressive effect at this period but also that CD4+ T-cells could be a primary target for ALV-J [167].

It has been previously observed that infection by ALV-J produces an inhibition of blood and splenic T-cell proliferation and cytotoxicity in broilers [199] and a reduction in CD4+ and an increase in CD8+ T-cell populations in the spleen [200]. Taking all the data together, it can be concluded that ALV-J exerts an immunosuppressive effect on both humoral and cellular responses and that 3–4 weeks post-infection may be the critical period for this ALV-J inducing immunosuppression.

All these results help to better understand the cellular immune response against ALV, although further studies are needed to elucidate the specific roles of T-cells against ALV during natural or experimental infections. A better knowledge and understanding of humoral and cellular immune responses may help to develop breeds with increased resistance to ALV and more effective vaccines.

References

- Payne, L.N.; Nair, V. The Long View: 40 Years of Avian Leukosis Research. Avian. Pathol. 2012, 41, 11–19.

- Feng, W.; Zhou, D.; Meng, W.; Li, G.; Zhuang, P.; Pan, Z.; Wang, G.; Cheng, Z. Growth Retardation Induced by Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J Associated with Down-Regulated Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 104, 48–55.

- Salter, D.; Balander, R.; Crittenden, L. Evaluation of Japanese Quail as a Model System for Avian Transgenesis Using Avian Leukosis Viruses. Poult. Sci. 1999, 78, 230–234.

- Zhang, J.; Ma, L.; Li, T.; Li, L.; Kan, Q.; Yao, X.; Xie, Q.; Wan, Z.; Shao, H.; Qin, A.; et al. Synergistic Pathogenesis of Chicken Infectious Anemia Virus and J Subgroup of Avian Leukosis Virus. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101468.

- Nair, V. Leukosis/Sarcoma Group. In Diseases of Poultry; Swayne, D.E., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 587–625.

- Ellermann, V.; Bang, O. Experimentelle Leukamie Bei Huhnern. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Parasitenkd. Infectionskr. Hyg. Abt. Orig. 2008, 46, 596–609.

- Rous, P. A Sarcoma of the Fowl Transmissible Byan Agent Separable from the Tumor Cells. J. Exp. Med. 1911, 13, 397–411.

- Rubin, H.; Vogt, P.K. An Avian Leukosis Virus Asso-Ciated with Stocks of Rous Sarcoma Virus. Virology 1962, 17, 184–194.

- Temin, H.M.; Rubin, H. Characteristics of an Assay for Rous Sarcoma Virus and Rous Sarcoma Cells in Tissue Culture. Virology 1958, 6, 669–688.

- Rubin, H. The Early History of Tumor Virology: Rous, RIF, and RAV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14389–14396.

- Temin, H.M.; Mizutani, S. Viral RNA-Dependent DNA Polymerase: RNA-Dependent DNA Polymerase in Virions of Rous Sarcoma Virus. Nature 1970, 226, 1211–1213.

- Baltimore, D. Viral RNA-Dependent DNA Polymerase: RNA-Dependent DNA Polymerase in Virions of RNA Tumour Viruses. Nature 1970, 226, 1209–1211.

- Engelbreth-Holm, J.; Meyer, A.R. On the Connection between Erythroblastosis (Haemocytoplastosis), Myelosis and Sarcoma in Chicken. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1935, 12, 352–365.

- Coffin, J.M.; Hughes, S.H.; Varmus, H.E. A Brief Chronicle of Retrovirology. In Retroviruses; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Woodbury, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 6–16. ISBN 0-87969-571-4.

- Frossard, J. Retroviridae. In Veterinary Microbiology; McVey, D.S., Kennedy, M., Chengappa, M.M., Wilkes, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 698–727. ISBN 978-1-119-65075-1.

- Malhotra, S.; Justice, J.; Lee, N.; Li, Y.; Zavala, G.; Ruano, M.; Morgan, R.; Beemon, K. Complete Genome Sequence of an American Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup j Isolate That Causes Hemangiomas and Myeloid Leukosis. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e01586-14.

- Pandiri, A.R.; Gimeno, I.M.; Mays, J.K.; Reed, W.M.; Fadly, A.M. Reversion to Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus Viremia in Seroconverted Adult Meat-Type Chickens Exposed to Chronic Stress by Adrenocorticotrophin Treatment. Avian Dis. 2012, 56, 578–582.

- Zheng, L.-P.; Teng, M.; Li, G.-X.; Zhang, W.-K.; Wang, W.-D.; Liu, J.-L.; Li, L.-Y.; Yao, Y.; Nair, V.; Luo, J. Current Epidemiology and Co-Infections of Avian Immunosuppressive and Neoplastic Diseases in Chicken Flocks in Central China. Viruses 2022, 14, 2599.

- Dong, X.; Zhao, P.; Li, W.; Chang, S.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Ju, S.; Sun, P.; Meng, F.; Liu, J.; et al. Diagnosis and Sequence Analysis of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J Isolated from Chinese Partridge Shank Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 668–672.

- Freick, M.; Schreiter, R.; Weber, J.; Vahlenkamp, T.W.; Heenemann, K. Avian Leukosis Virus (ALV) Is Highly Prevalent in Fancy-Chicken Flocks in Saxony. Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 1169–1174.

- Mo, G.; Wei, P.; Hu, B.; Nie, Q.; Zhang, X. Advances on Genetic and Genomic Studies of ALV Resistance. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 123.

- Deng, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Wang, P.; Fu, F.; Zhu, W.; Wei, T.; Mo, M.; Huang, T.; et al. The Emergence, Diversification, and Transmission of Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus Reveals That the Live Chicken Trade Plays a Critical Role in the Adaption and Endemicity of Viruses to the Yellow-Chickens. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e00717-22.

- Gilka, F.; Spencer, J.L. Chronic Myocarditis and Circulatory Syndrome in a White Leghorn Strain Induced by an Avian Leukosis Virus: Light and Electron Microscopic Study. Avian Dis. 1990, 34, 174.

- Chesters, P.M.; Smith, L.P.; Nair, V. E (XSR) Element Contributes to the Oncogenicity of Avian Leukosis Virus (Subgroup J). J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 2685–2692.

- Hayward, W.S.; Neel, B.G.; Astrin, S.M. Activation of a Cellular Onc Gene by Promoter Insertion in ALV-Induced Lymphoid Leukosis. Nature 1981, 290, 475–480.

- Hussain, A.I.; Johnson, J.A.; Da Silva Freire, M.; Heneine, W. Identification and Characterization of Avian Retroviruses in Chicken Embryo-Derived Yellow Fever Vaccines: Investigation of Transmission to Vaccine Recipients. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 1105–1111.

- Shahabuddin, M.; Sears, J.F.; Khan, A.S. No Evidence of Infectious Retroviruses in Measles Virus Vaccines Produced in Chicken Embryo Cell Cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 675–684.

- Hussain, A.I.; Shanmugam, V.; Switzer, W.M.; Tsang, S.X.; Fadly, A.; Thea, D.; Helfand, R.; Bellini, W.J.; Folks, T.M.; Heneine, W. Lack of Evidence of Endogenous Avian Leukosis Virus and Endogenous Avian Retrovirus Transmission to Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccine Recipients. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 66–72.

- Schat, K.A.; Erb, H.N. Lack of Evidence That Avian Oncogenic Viruses Are Infectious for Humans: A Review. Avian Dis. 2014, 58, 345–358.

- Silva, R.F.; Fadly, A.M.; Taylor, S.P. Development of a Polymerase Chain Reaction to Differentiate Avian Leukosis Virus (ALV) Subgroups: Detection of an ALV Contaminant in Commercial Marek’s Disease Vaccines. Avian Dis. 2007, 51, 663–667.

- Wang, P.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Bi, Y.; Lin, L.; Shi, M.; Huang, T.; Mo, M.; Wei, T.; Wei, P. ALV-J-Contaminated Commercial Live Vaccines Induced Pathogenicity in Three-Yellow Chickens: One of the Transmission Routes of ALV-J to Commercial Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101027.

- Mao, Y.; Su, Q.; Li, J.; Jiang, T.; Wang, Y. Avian Leukosis Virus Contamination in Live Vaccines: A Retrospective Investigation in China. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 246, 108712.

- Tang, S.; Li, J.; Chang, Y.-F.; Lin, W. Avian Leucosis Virus-Host Interaction: The Involvement of Host Factors in Viral Replication. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 907287.

- Rubin, H.; Fanshier, L.; Cornelius, A.; Hughes, W.F. Tolerance and Immunity in Chickens after Congenital and Contact Infection with an Avian Leukosis Virus. Virology 1962, 17, 143–156.

- Li, Y.; Cui, S.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Zhao, P.; Chang, S. Vertical Transmission of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J (ALV-J) from Hens Infected through Artificial Insemination with ALV-J Infected Semen. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 204.

- Bacon, L.D.; Smith, E.; Crittenden, L.B.; Havenstein, G.B. Association of the Slow Feathering (K) and an Endogenous Viral (Ev 21) Gene on the Z Chromosome of Chickens. Poult. Sci. 1988, 67, 191–197.

- Huda, A.; Polavarapu, N.; Jordan, I.K.; McDonald, J.F. Endogenous Retroviruses of the Chicken Genome. Biol. Direct. 2008, 3, 9.

- Federspiel, M.J. Reverse Engineering Provides Insights on the Evolution of Subgroups A to E Avian Sarcoma and Leukosis Virus Receptor Specificity. Viruses 2019, 11, 497.

- Fenton, S.P.; Reddy, M.R.; Bagust, T.J. Single and Concurrent Avian Leukosis Virus Infections with Avian Leukosis Virus-J and Avian Leukosis Virus-A in Australian Meat-Type Chickens. Avian Pathol. 2005, 34, 48–54.

- Deng, Q.; Li, M.; He, C.; Lu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Shi, M.; Wang, P.; Wei, P. Genetic Diversity of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J (ALV-J): Toward a Unified Phylogenetic Classification and Nomenclature System. Virus Evol. 2021, 7, veab037.

- Chang, S.-W.; Hsu, M.-F.; Wang, C.-H. Gene Detection, Virus Isolation, and Sequence Analysis of Avian Leukosis Viruses in Taiwan Country Chickens. Avian Dis. 2013, 57, 172–177.

- Su, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Cui, S.; Tian, S.; Cui, Z.; Zhao, P.; Chang, S. Molecular Characteristics of Avian Leukosis Viruses Isolated from Indigenous Chicken Breeds in China. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 2917–2925.

- Burmester, B.R.; Walter, W.G.; Gross, M.A.; Fontes, A.K. The Oncogenic Spectrum of Two Pure Strains of Avian Leukosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1959, 23, 277–291.

- Purchase, H.G.; Okazaki, W.; Vogt, P.K.; Hanafusa, H.; Burmester, B.R.; Crittenden, L.B. Oncogenicity of Avian Leukosis Viruses of Different Subgroups and of Mutants of Sarcoma Viruses. Infect. Immun. 1977, 15, 423–428.

- Nakamura, S.; Ochiai, K.; Abe, A.; Kishi, S.; Takayama, K.; Sunden, Y. Astrocytic Growth through the Autocrine/Paracrine Production of IL-1β in the Early Infectious Phase of Fowl Glioma-Inducing Virus. Avian Pathol. 2014, 43, 437–442.

- Ma, M.; Yu, M.; Chang, F.; Xing, L.; Bao, Y.; Wang, S.; Farooque, M.; Li, X.; Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J in Chinese Local Chickens between 2013 and 2018. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5286–5296.

- Payne, L.N.; Brown, S.R.; Bumstead, N.; Howes, K.; Frazier, J.A.; Thouless, M.E. A Novel Subgroup of Exogenous Avian Leukosis Virus in Chickens. J. Gen. Virol. 1991, 72 Pt 4, 801–807.

- Xu, B.; Dong, W.; Yu, C.; He, Z.; Lv, Y.; Sun, Y.; Feng, X.; Li, N.; Lee, L.F.; Li, M. Occurrence of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J in Commercial Layer Flocks in China. Avian Pathol. 2004, 33, 13–17.

- Lai, H.; Zhang, H.; Ning, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhang, W.; Qing, A.; Xin, C.; Yu, K.; Cao, W.; Liao, M. Isolation and Characterization of Emerging Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus Associated with Hemangioma in Egg-Type Chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 151, 275–283.

- Bai, J.; Payne, L.N.; Skinner, M.A. HPRS-103 (Exogenous Avian Leukosis Virus, Subgroup J) Has an Env Gene Related to Those of Endogenous Elements EAV-0 and E51 and an E Element Found Previously Only in Sarcoma Viruses. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 779–784.

- Benson, S.J.; Ruis, B.L.; Garbers, A.L.; Fadly, A.M.; Conklin, K.F. Independent Isolates of the Emerging Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus Derive from a Common Ancestor. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 10301–10304.

- Yao, Y.; Smith, L.P.; Nair, V.; Watson, M. An Avian Retrovirus Uses Canonical Expression and Processing Mechanisms to Generate Viral MicroRNA. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 2–9.

- Meng, F.; Li, X.; Fang, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xing, G.; Tian, F.; Gao, Y.; Dong, X.; Chang, S.; et al. Genomic Diversity of the Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J Gp85 Gene in Different Organs of an Infected Chicken. J. Vet. Sci. 2016, 17, 497–503.

- Borodin, A.M.; Emanuilova, Z.V.; Smolov, S.V.; Ogneva, O.A.; Konovalova, N.V.; Terentyeva, E.V.; Serova, N.Y.; Efimov, D.N.; Fisinin, V.I.; Greenberg, A.J.; et al. Eradication of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroups J and K in Broiler Cross Chickens by Selection against Infected Birds Using Multilocus PCR. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269525.

- Wang, P.; Lin, L.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, T.; Wei, P. Diversity and Evolution Analysis of Glycoprotein GP85 from Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J Isolates from Chickens of Different Genetic Backgrounds during 1989–2016: Coexistence of Five Extremely Different Clusters. Arch. Virol. 2018, 163, 377–389.

- Wang, X.; Zhao, P.; Cui, Z.-Z. Identification of a new subgroup of avian leukosis virus isolated from Chinese indigenous chicken breeds. Chin. J. Virol. 2012, 28, 609–614.

- Li, X.; Lin, W.; Chang, S.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, B.; Shu, D.; Zhang, H.; et al. Isolation, Identification and Evolution Analysis of a Novel Subgroup of Avian Leukosis Virus Isolated from a Local Chinese Yellow Broiler in South China. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 2717–2725.

- Chen, J.; Li, J.; Dong, X.; Liao, M.; Cao, W. The Key Amino Acid Sites 199-205, 269, 319, 321 and 324 of ALV-K Env Contribute to the Weaker Replication Capacity of ALV-K than ALV-A. Retrovirology 2022, 19, 19.

- Liang, X.; Gu, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, T.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Fang, C.; Fang, S.; Yang, Y. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Natural Recombinant Avian Leucosis Virus from Chinese Indigenous Chicken Flock. Virus Genes 2019, 55, 726–733.

- Mason, A.S.; Fulton, J.E.; Hocking, P.M.; Burt, D.W. A New Look at the LTR Retrotransposon Content of the Chicken Genome. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 688.

- Hu, X.; Zhu, W.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Geng, T.; Song, C.; Gao, B.; Wang, X.; Qin, A.; et al. Expression Patterns of Endogenous Avian Retrovirus ALVE1 and Its Response to Infection with Exogenous Avian Tumour Viruses. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 89–101.

- Mason, A.S.; Lund, A.R.; Hocking, P.M.; Fulton, J.E.; Burt, D.W. Identification and Characterisation of Endogenous Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup E (ALVE) Insertions in Chicken Whole Genome Sequencing Data. Mob. DNA 2020, 11, 22.

- Smith, E.J.; Fadly, A.M.; Levin, I.; Crittenden, L.B. The Influence of Ev 6 on the Immune Response to Avian Leukosis Virus Infection in Rapid-Feathering Progeny of Slow- and Rapid-Feathering Dams. Poult. Sci. 1991, 70, 1673–1678.

- Elferink, M.G.; Vallée, A.A.A.; Jungerius, A.P.; Crooijmans, R.P.M.A.; Groenen, M.A.M. Partial Duplication of the PRLR and SPEF2 Genes at the Late Feathering Locus in Chicken. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 391.

- Bu, G.; Huang, G.; Fu, H.; Li, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y. Characterization of the Novel Duplicated PRLR Gene at the Late-Feathering K Locus in Lohmann Chickens. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 51, 261–276.

- Harris, D.L.; Garwood, V.A.; Lowe, P.C.; Hester, P.Y.; Crittenden, L.B.; Fadly, A.M. Influence of Sex-Linked Feathering Phenotypes of Parents and Progeny Upon Lymphoid Leukosis Virus Infection Status and Egg Production. Poult. Sci. 1984, 63, 401–413.

- Mays, J.K.; Black-Pyrkosz, A.; Mansour, T.; Schutte, B.C.; Chang, S.; Dong, K.; Hunt, H.D.; Fadly, A.M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H. Endogenous Avian Leukosis Virus in Combination with Serotype 2 Marek’s Disease Virus Significantly Boosted the Incidence of Lymphoid Leukosis-Like Bursal Lymphomas in Susceptible Chickens. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00861-19.

- Cao, W.; Mays, J.; Kulkarni, G.; Dunn, J.; Fulton, R.M.; Fadly, A. Further Observations on Serotype 2 Marek’s Disease Virus-Induced Enhancement of Spontaneous Avian Leukosis Virus-like Bursal Lymphomas in ALVA6 Transgenic Chickens. Avian Pathol. 2015, 44, 23–27.

- Ramoutar, V.V.; Johnson, Y.J.; Kohrt, L.J.; Bahr, J.M.; Iwai, A.; Caporali, E.H.G.; Myint, M.S.; Szigetvari, N.; Stewart, M.C. Retroviral Association with Ovarian Adenocarcinoma in Laying Hens. Avian Pathol. 2022, 51, 113–119.

- Fulton, J.E.; Mason, A.S.; Wolc, A.; Arango, J.; Settar, P.; Lund, A.R.; Burt, D.W. The Impact of Endogenous Avian Leukosis Viruses (ALVE) on Production Traits in Elite Layer Lines. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101121.

- Gavora, J.S.; Kuhnlein, U.; Crittenden, L.B.; Spencer, J.L.; Sabour, M.P. Endogenous Viral Genes: Association with Reduced Egg Production Rate and Egg Size in White Leghorns. Poult. Sci. 1991, 70, 618–623.

- Kuhnlein, U.; Sabour, M.; Gavora, J.S.; Fairfull, R.W.; Bernon, D.E. Influence of Selection for Egg Production and Marek’s Disease Resistance on the Incidence of Endogenous Viral Genes in White Leghorns. Poult. Sci. 1989, 68, 1161–1167.

- Fox, W.; Smyth, J.R. The Effects of Recessive White and Dominant White Genotypes on Early Growth Rate. Poult. Sci. 1985, 64, 429–433.

- Ka, S.; Kerje, S.; Bornold, L.; Liljegren, U.; Siegel, P.B.; Andersson, L.; Hallböök, F. Proviral Integrations and Expression of Endogenous Avian Leucosis Virus during Long Term Selection for High and Low Body Weight in Two Chicken Lines. Retrovirology 2009, 6, 68.

- Mason, A.S.; Miedzinska, K.; Kebede, A.; Bamidele, O.; Al-Jumaili, A.S.; Dessie, T.; Hanotte, O.; Smith, J. Diversity of Endogenous Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup E (ALVE) Insertions in Indigenous Chickens. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2020, 52, 29.

- Aswad, A.; Katzourakis, A. Paleovirology and Virally Derived Immunity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 627–636.

- Chiu, E.S.; VandeWoude, S. Endogenous Retroviruses Drive Resistance and Promotion of Exogenous Retroviral Homologs. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 9, 225–248.

- Chen, S.; Hu, X.; Cui, I.H.; Wu, S.; Dou, C.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xue, S.; Geng, T.; Liu, Z.; et al. An Endogenous Retroviral Element Exerts an Antiviral Innate Immune Function via the Derived LncRNA Lnc-ALVE1-AS1. Antivir. Res. 2019, 170, 104571.

- Benkel, B.F. Locus-Specific Diagnostic Tests for Endogenous Avian Leukosis-Type Viral Loci in Chickens. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 1027–1035.

- Rutherford, K.; Meehan, C.J.; Langille, M.G.I.; Tyack, S.G.; McKay, J.C.; McLean, N.L.; Benkel, K.; Beiko, R.G.; Benkel, B. Discovery of an Expanded Set of Avian Leukosis Subgroup E Proviruses in Chickens Using Vermillion, a Novel Sequence Capture and Analysis Pipeline. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 2250–2258.

- Mason, A.S. The Abundance and Diversity of Endogenous Retroviruses in the Chicken Genome. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2018.

- Shao, H.; Wang, L.; Sang, J.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Qian, K.; Qin, A.; Ye, J. Novel Avian Leukosis Viruses from Domestic Chicken Breeds in Mainland China. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 2073–2076.

- Wang, P.; Niu, J.; Xue, C.; Han, Z.; Abdelazez, A.; Xinglin, Z. Two Novel Recombinant Avian Leukosis Virus Isolates from Luxi Gamecock Chickens. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 2877–2881.

- Cai, L.; Shen, Y.; Wang, G.; Guo, H.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Z. Identification of Two Novel Multiple Recombinant Avian Leukosis Viruses in Two Different Lines of Layer Chicken. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 2278–2286.

- Li, J.; Liu, L.; Niu, X.; Li, J.; Kang, Z.; Han, C.; Gao, Y.; Qi, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Research Note: A Novel Recombinant Subgroup E Isolate of the Avian Leukosis Virus with a Subgroup B-like Gp85 Region in China. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101137.

- Barbosa, T.; Zavala, G.; Cheng, S. Molecular Characterization of Three Recombinant Isolates of Avian Leukosis Virus Obtained from Contaminated Marek’s Disease Vaccines. Avian Dis. 2008, 52, 245–252.

- Wang, P.; Shi, M.; He, C.; Lin, L.; Li, H.; Gu, Z.; Li, M.; Gao, Y.; Huang, T.; Mo, M.; et al. A Novel Recombinant Avian Leukosis Virus Isolated from Gamecocks Induced Pathogenicity in Three-Yellow Chickens: A Potential Infection Source of Avian Leukosis Virus to the Commercial Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 6497–6504.

- M. Landman, W.J.; Nieuwenhuisen-van Wilgen, J.L.; Koch, G.; Dwars, R.M.; Ultee, A.; Gruys, E. Avian Leukosis Virus Subtype J in Ovo-Infected Specific Pathogen Free Broilers Harbour the Virus in Their Feathers and Show Feather Abnormalities. Avian Pathol. 2001, 30, 675–684.

- Murphy, B. Retroviridae. In Fenner’s Veterinary Virology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 269–297. ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8.

- Brown, D.W.; Blais, B.P.; Robinson, H.L. Long Terminal Repeat (LTR) Sequences, Env, and a Region near the 5’ LTR Influence the Pathogenic Potential of Recombinants between Rous-Associated Virus Types 0 and 1. J. Virol. 1988, 62, 3431–3437.

- Mingzhang, R.; Zijun, Z.; Lixia, Y.; Jian, C.; Min, F.; Jie, Z.; Ming, L.; Weisheng, C. The Construction and Application of a Cell Line Resistant to Novel Subgroup Avian Leukosis Virus (ALV-K) Infection. Arch. Virol. 2018, 163, 89–98.

- Zhao, Z.; Rao, M.; Liao, M.; Cao, W. Phylogenetic Analysis and Pathogenicity Assessment of the Emerging Recombinant Subgroup K of Avian Leukosis Virus in South China. Viruses 2018, 10, 194.

- Swanstrom, R.; Graham, W.D.; Zhou, S. Sequencing the Biology of Entry: The Retroviral Env Gene. Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 2017, 407, 65–82.

- Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Fang, X.; Gao, K.; Fang, C.; Gu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, H.; Liang, X.; et al. Identification of a Novel Epitope Specific for Gp85 Protein of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup K. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2020, 230, 110143.

- Ronfort, C.; Afanassieff, M.; Chebloune, Y.; Dambrine, G.; Nigon, V.M.; Verdier, G. Identification and Structure Analysis of Endogenous Proviral Sequences in a Brown Leghorn Chicken Strain. Poult. Sci. 1991, 70, 2161–2175.

- Böhnlein, S.; Hauber, J.; Cullen, B.R. Identification of a U5-Specific Sequence Required for Efficient Polyadenylation within the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Long Terminal Repeat. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 421–424.

- Ruddell, A. Transcription Regulatory Elements of the Avian Retroviral Long Terminal Repeat. Virology 1995, 206, 1–7.

- Deffaud, C.; Darlix, J.-L. Rous Sarcoma Virus Translation Revisited: Characterization of an Internal Ribosome Entry Segment in the 5′ Leader of the Genomic RNA. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 11581–11588.

- Gomez-Lucia, E.; Ocaña, J.; Benitez, L.; Fandiño, S.; Domenech, A. In Silico Analysis Reveals the Similarity of Transcription Binding Site Motifs in Endogenous and Exogenous Gammaretroviruses from Different Animal Species. Biochem. Genet. 2023; under review.

- Gómez-Lucía, E.; Collado, V.M.; Miró, G.; Doménech, A. Effect of Type-I Interferon on Retroviruses. Viruses 2009, 1, 545–573.

- Fandiño, S.; Gomez-Lucia, E.; Lumbreras, J.; Benitez, L.; Domenech, A. Analysis of Transcription Binding Sites Present in the Long Terminal Repeats of Different Avian Leukosis Viruses in Various Bird Species. manuscript in preparation.

- Platanias, L.C. Mechanisms of Type-I- and Type-II-Interferon-Mediated Signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 375–386.

- Uddin, S.; Lekmine, F.; Sassano, A.; Rui, H.; Fish, E.N.; Platanias, L.C. Role of Stat5 in Type I Interferon-Signaling and Transcriptional Regulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 308, 325–330.

- Kawasaki, T.; Kawai, T. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathways. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 461.

- De Bosscher, K.; Vanden Berghe, W.; Vermeulen, L.; Plaisance, S.; Boone, E.; Haegeman, G. Glucocorticoids Repress NF-ΚB-Driven Genes by Disturbing the Interaction of P65 with the Basal Transcription Machinery, Irrespective of Coactivator Levels in the Cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 3919–3924.

- Chikhirzhina, G.I.; Al-Shekhadat, R.I.; Chikhirzhina, E.V. Transcription Factors of the NF1 Family: Role in Chromatin Remodeling. Mol. Biol. 2008, 42, 342–356.

- Ma, X.; Montaner, L.J. Proinflammatory Response and IL-12 Expression in HIV-1 Infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000, 68, 383–390.

- Malhotra, S.; Winans, S.; Lam, G.; Justice, J.; Morgan, R.; Beemon, K. Selection for Avian Leukosis Virus Integration Sites Determines the Clonal Progression of B-Cell Lymphomas. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006708.

- Clurman, B.E.; Hayward, W.S. Multiple Proto-Oncogene Activations in Avian Leukosis Virus- Induced Lymphomas: Evidence for Stage-Specific Events. Mol. Cell Biol. 1989, 9, 2657–2664.

- Miklík, D.; Šenigl, F.; Hejnar, J. Proviruses with Long-Term Stable Expression Accumulate in Transcriptionally Active Chromatin Close to the Gene Regulatory Elements: Comparison of ASLV-, HIV- and MLV-Derived Vectors. Viruses 2018, 10, 116.

- Justice, J.; Malhotra, S.; Ruano, M.; Li, Y.; Zavala, G.; Lee, N.; Morgan, R.; Beemon, K. The MET Gene Is a Common Integration Target in Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J-Induced Chicken Hemangiomas. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 4712–4719.

- Jiang, L.; Zeng, X.; Hua, Y.; Gao, Q.; Fan, Z.; Chai, H.; Wang, Q.; Qi, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Phylogenetic Analysis of Glycoprotein Gp85 of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J Wild-Bird Isolates from Northeast China. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 1821–1826.

- Meng, F.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, S.; Cui, Z.; Chang, S.; Zhao, P. Characterization of Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus Isolated from Chinese Indigenous Chickens. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 33.

- Yehia, N.; El-Sayed, H.S.; Omar, S.E.; Amer, F. Genetic Variability of the Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J Gp85 Gene in Layer Flocks in Lower Egypt. Vet. World 2020, 13, 1065–1072.

- Cui, Z.; Sun, S.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, S. Simultaneous Endemic Infections with Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus and Reticuloendotheliosis Virus in Commercial and Local Breeds of Chickens. Avian Pathol. 2009, 38, 443–448.

- Payne, L.N. Developments in Avian Leukosis Research. Leukemia 1992, 6 (Suppl. S3), 150S–152S.

- Dong, X.; Zhao, P.; Xu, B.; Fan, J.; Meng, F.; Sun, P.; Ju, S.; Li, Y.; Chang, S.; Shi, W.; et al. Avian Leukosis Virus in Indigenous Chicken Breeds, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2015, 4, e76.

- Lv, L.; Li, T.; Hu, M.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Q.; Shao, H.; Ye, J.; Qin, A. A Recombination Efficiently Increases the Pathogenesis of the Novel K Subgroup of Avian Leukosis Virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 231, 214–217.

- Su, Q.; Li, Y.; Cui, Z.; Chang, S.; Zhao, P. The Emerging Novel Avian Leukosis Virus with Mutations in the Pol Gene Shows Competitive Replication Advantages Both in Vivo and in Vitro. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 117.

- Ayala, A.J.; Yabsley, M.J.; Hernandez, S.M. A Review of Pathogen Transmission at the Backyard Chicken–Wild Bird Interface. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 539925.

- Pohjola, L.; Rossow, L.; Huovilainen, A.; Soveri, T.; Hänninen, M.-L.; Fredriksson-Ahomaa, M. Questionnaire Study and Postmortem Findings in Backyard Chicken Flocks in Finland. Acta Vet. Scand. 2015, 57, 3.

- Smith, L.P.; Petheridge, L.; Nair, V.; Wood, A.; Welchman, D. Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J-Associated Myelocytoma in a Hobby Chicken. Vet. Rec. 2018, 182, 23.

- Williams, S.M.; Barbosa, T.; Hafner, S.; Zavala, G. Myxosarcomas Associated with Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup A Infection in Fancy Breed Chickens. Avian Dis. 2010, 54, 1319–1322.

- Mete, A.; Giannitti, F.; Barr, B.; Woods, L.; Anderson, M. Causes of Mortality in Backyard Chickens in Northern California: 2007–2011. Avian Dis. 2013, 57, 311–315.

- Cadmus, K.J.; Mete, A.; Harris, M.; Anderson, D.; Davison, S.; Sato, Y.; Helm, J.; Boger, L.; Odani, J.; Ficken, M.D.; et al. Causes of Mortality in Backyard Poultry in Eight States in the United States. J. VET Diagn. Investg. 2019, 31, 318–326.

- Wunderwald, C.; Hoop, R.K. Serological Monitoring of 40 Swiss Fancy Breed Poultry Flocks. Avian Pathol. 2002, 31, 157–162.

- de Wit, J.J.; van Eck, J.H.; Crooijmans, R.P.; Pijpers, A. A Serological Survey for Pathogens in Old Fancy Chicken Breeds in Central and Eastern Part of The Netherlands. Tijdschr. Diergeneeskd 2004, 129, 324–327.

- Payne, L.N.; Howes, K.; Gillespie, A.M.; Smith, L.M. Host Range of Rous Sarcoma Virus Pseudotype RSV(HPRS-103) in 12 Avian Species: Support for a New Avian Retrovirus Envelope Subgroup, Designated J. J. Gen. Virol. 1992, 73, 2995–2997.

- Melder, D.C.; Pankratz, V.S.; Federspiel, M.J. Evolutionary Pressure of a Receptor Competitor Selects Different Subgroup a Avian Leukosis Virus Escape Variants with Altered Receptor Interactions. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10504–10514.

- Plachý, J.; Reinišová, M.; Kučerová, D.; Šenigl, F.; Stepanets, V.; Hron, T.; Trejbalová, K.; Elleder, D.; Hejnar, J. Identification of New World Quails Susceptible to Infection with Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e02002-16.

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, W.; Li, B.; Chen, R.; Shen, W.; Guo, H.; Guo, H.; Li, H. Comparison of Viremia, Cloacal Virus Shedding, Antibody Responses and Pathological Lesions in Adult Chickens, Quails, and Pigeons Infected with ALV-A. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3027.

- Venugopal, K.; Howes, K.; Flannery, D.M.J.; Payne, L.N. Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus Infection in Turkeys: Induction of Rapid Onset Tumours by Acutely Transforming Virus Strain 966. Avian Pathol. 2000, 29, 319–325.

- Zeghdoudi, M.; Aoun, L.; Merdaci, L.; Bouzidi, N. Epidemiological Features and Pathological Study of Avian Leukosis in Turkeys’ Flocks. Vet. World 2017, 10, 1135–1138.

- Li, D.; Qin, L.; Gao, H.; Yang, B.; Liu, W.; Qi, X.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup A and B Infection in Wild Birds of Northeast China. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 163, 257–263.

- Shen, Y.; He, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, M.; Wang, G.; Cheng, Z. Cross-species Transmission of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J. Chin. J. Virol. 2016, 32, 46–55.

- Shen, Y.; Cai, L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, R.; He, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Cheng, Z. Genetic Mutations of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J Strains Extended Their Host Range. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 691–699.

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Dong, X.; Liang, C.; Guo, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, M.; Liao, M.; Cao, W. Residues 140–142, 199–200, 222–223, and 262 in the Surface Glycoprotein of Subgroup A Avian Leukosis Virus Are the Key Sites Determining Tva Receptor Binding Affinity and Infectivity. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 868377.

- Han, C.; Hao, R.; Liu, L.; Zeng, X. Molecular Characterization of 3’UTRs of J Subgroup Avian Leukosis Virus in Passerine Birds in China. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 845–849.

- Zeng, X.; Liu, L.; Hao, R.; Han, C. Detection and Molecular Characterization of J Subgroup Avian Leukosis Virus in Wild Ducks in China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94980.

- Reinišová, M.; Plachý, J.; Kučerová, D.; Šenigl, F.; Vinkler, M.; Hejnar, J. Genetic Diversity of NHE1, Receptor for Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus, in Domestic Chicken and Wild Anseriform Species. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150589.

- Khordadmehr, M.; Firouzamandi, M.; Zehtab-Najafi, M.; Shahbazi, R. Naturally Occurring Co-Infection of Avian Leukosis Virus (Subgroups A–E) and Reticuloendotheliosis Virus in Green Peafowls (Pavo muticus). Rev. Bras. Cienc. Avic. 2017, 19, 609–614.

- García-Fernández, R.A.; Pérez-Martínez, C.; Espinosa-Alvarez, J.; Escudero-Diez, A.; García-Marín, J.F.; Núñez, A.; García-Iglesias, M.J. Lymphoid Leukosis in an Ostrich (Struthio camelus). Vet. Rec. 2000, 146, 676–677.

- Frisby, D.P.; Weiss, R.A.; Roussel, M.; Stehelin, D. The Distribution of Endogenous Chicken Retrovirus Sequences in the DNA of Galliform Birds Does Not Coincide with Avian Phylogenetic Relationships. Cell 1979, 17, 623–634.

- Fujita, D.J.; Tal, J.; Varmus, H.E.; Bishop, J.M. Env Gene of Chicken RNA Tumor Viruses: Extent of Conservation in Cellular and Viral Genomes. J. Virol. 1978, 27, 465–474.

- Hanafusa, T.; Hanafusa, H. Isolation of Leukosis-Type Virus from Pheasant Embryo Cells: Possible Presence of Viral Genes in Cells. Virology 1973, 51, 247–251.

- Fujita, D.J.; Chen, Y.C.; Friis, R.R.; Vogt, P.K. RNA Tumor Viruses of Pheasants: Characterization of Avian Leukosis Subgroups F and G. Virology 1974, 60, 558–571.

- Payne, L.N. Biology of Avian Retroviruses. In The Retroviridae; Levy, J.A., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 1, pp. 299–404.

- Dimcheff, D.E.; Drovetski, S.V.; Krishnan, M.; Mindell, D.P. Cospeciation and Horizontal Transmission of Avian Sarcoma and Leukosis Virus Gag Genes in Galliform Birds. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 3984–3995.

- Dimcheff, D.E.; Krishnan, M.; Mindell, D.P. Evolution and Characterization of Tetraonine Endogenous Retrovirus: A New Virus Related to Avian Sarcoma and Leukosis Viruses. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 2002–2009.

- Zhu, F.; Jie, H.; Lian, L.; Qu, L.J.; Hou, Z.C.; Zheng, J.X.; Chen, S.Y.; Yang, N.; Liu, Y.P. Avian Sarcoma and Leukosis Virus Gag Gene in the Anser Anser Domesticus Genome. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 14379–14386.

- Elleder, D.; Hejnar, J. Letter to the Editor: Avian sarcoma and leukosis virus gag gene—Genet. Mol. Res. 14 (4): 14379-14386 “Avian sarcoma and leukosis virus gag gene in the Anser anser domesticus genome”. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 15014956.

- Hao, R.; Han, C.; Liu, L.; Zeng, X. First Finding of Subgroup-E Avian Leukosis Virus from Wild Ducks in China. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 173, 366–370.

- Payne, L.N. Epizootiology of Avian Leukosis Virus Infections. In Avian Leukosis; Martinus Nijhoff Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1987; pp. 47–75.

- Barnard, R.J.O.; Elleder, D.; Young, J.A.T. Avian Sarcoma and Leukosis Virus-Receptor Interactions: From Classical Genetics to Novel Insights into Virus-Cell Membrane Fusion. Virology 2006, 344, 25–29.

- Holmen, S.L.; Federspiel, M.J. Selection of a Subgroup A Avian Leukosis Virus Envelope Resistant to Soluble ALV(A) Surface Glycoprotein. Virology 2000, 273, 364–373.

- Přikryl, D.; Plachý, J.; Kučerová, D.; Koslová, A.; Reinišová, M.; Šenigl, F.; Hejnar, J. The Novel Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup K Shares Its Cellular Receptor with Subgroup A. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00580-19.

- Holmen, S.L.; Melder, D.C.; Federspiel, M.J. Identification of Key Residues in Subgroup A Avian Leukosis Virus Envelope Determining Receptor Binding Affinity and Infectivity of Cells Expressing Chicken or Quail Tva Receptor. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 726–737.

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, K.Y.; Park, Y.H.; Choi, H.J.; Yao, Y.; Nair, V.; Han, J.Y. Acquisition of Resistance to Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup B through Mutations on Tvb Cysteine-Rich Domains in DF-1 Chicken Fibroblasts. Vet. Res. 2017, 48, 48.

- Brojatsch, J.; Naughton, J.; Adkins, H.B.; Young, J.A.T. TVB Receptors for Cytopathic and Noncytopathic Subgroups of Avian Leukosis Viruses Are Functional Death Receptors. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 11490–11494.

- Munguia, A.; Federspiel, M.J. Efficient Subgroup C Avian Sarcoma and Leukosis Virus Receptor Activity Requires the IgV Domain of the Tvc Receptor and Proper Display on the Cell Membrane. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11419–11428.

- Chai, N.; Bates, P. Na+/H+ Exchanger Type 1 Is a Receptor for Pathogenic Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 5531–5536.

- Putney, L.K.; Denker, S.P.; Barber, D.L. The Changing Face of the Na + /H + Exchanger, NHE1: Structure, Regulation, and Cellular Actions. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002, 42, 527–552.

- Kučerová, D.; Plachý, J.; Reinišová, M.; Šenigl, F.; Trejbalová, K.; Geryk, J.; Hejnar, J. Nonconserved Tryptophan 38 of the Cell Surface Receptor for Subgroup J Avian Leukosis Virus Discriminates Sensitive from Resistant Avian Species. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 8399–8407.

- Mei, M.; Ye, J.; Qin, A.; Wang, L.; Hu, X.; Qian, K.; Shao, H. Identification of Novel Viral Receptors with Cell Line Expressing Viral Receptor-Binding Protein. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7935.

- Rup, B.J.; Hoelzer, J.D.; Bose, H.R. Helper Viruses Associated with Avian Acute Leukemia Viruses Inhibit the Cellular Immune Response. Virology 1982, 116, 61–71.

- Feng, M.; Dai, M.; Xie, T.; Li, Z.; Shi, M.; Zhang, X. Innate Immune Responses in ALV-J Infected Chicks and Chickens with Hemangioma In Vivo. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 786.

- Feng, M.; Zhang, X. Immunity to Avian Leukosis Virus: Where Are We Now and What Should We Do? Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 624.

- Wang, H.; Li, W.; Zheng, S.J. Advances on Innate Immune Evasion by Avian Immunosuppressive Viruses. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 901913.

- Haugh, K.A.; Shalginskikh, N.; Nogusa, S.; Skalka, A.M.; Katz, R.A.; Balachandran, S. The Interferon-Inducible Antiviral Protein Daxx Is Not Essential for Interferon-Mediated Protection against Avian Sarcoma Virus. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 100.

- Zhu, M.; Ma, X.; Cui, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, C.; Huang, L.; Shang, Y.; Cheng, Z. Inhibition of Avian Tumor Virus Replication by CCCH-Type Zinc Finger Antiviral Protein. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 58865–58871.

- Li, L.; Feng, W.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, J.; Bi, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, G. TRIM62-Mediated Restriction of Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J Replication Is Dependent on the SPRY Domain. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 6019–6025.

- Zhou, J.-R.; Liu, J.-H.; Li, H.-M.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Hou, Y.-M.; Guo, H.-J. Regulatory Effects of Chicken TRIM25 on the Replication of ALV-A and the MDA5-Mediated Type I Interferon Response. Vet. Res. 2020, 51, 145.

- Xie, T.; Feng, M.; Dai, M.; Mo, G.; Ruan, Z.; Wang, G.; Shi, M.; Zhang, X. Cholesterol-25-Hydroxylase Is a Chicken ISG That Restricts ALV-J Infection by Producing 25-Hydroxycholesterol. Viruses 2019, 11, 498.

- Krchlíková, V.; Fábryová, H.; Hron, T.; Young, J.M.; Koslová, A.; Hejnar, J.; Strebel, K.; Elleder, D. Antiviral Activity and Adaptive Evolution of Avian Tetherins. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e00416-20.