| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tiziana Cervelli | -- | 2311 | 2023-07-31 11:19:40 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | + 1 word(s) | 2312 | 2023-08-01 03:01:16 | | |

Video Upload Options

Several structural viral proteins can self-assemble to form a capsid without a viral genome. This property of viral proteins has been exploited for constructing virus-like particles (VLPs). The most important feature of VLPs is that they resemble the capsid of the original virus, but they are empty shells that do not contain the viral genome, and thus, they elicit an immune response without propagating inside the cells. VLPs have been produced in Escherichia coli and in mammalian, plant, insect, and yeast cells .

1. General Considerations of Yeast as Expression System

Table 1. List of virus proteins that have been expressed in yeast species to produce VLPs, grouped according to virus family.

| Family | Virus Species |

|---|---|

| Hepadnaviridae | Hepatitis B Virus, Hepatitis E Virus, |

| Flaviviridae | Hepatitis C Virus, Japanese Encephalitis Virus, Bovine Viral diarrhea virus, Tick-borne encephalitis virus, Zika virus |

| Papillomaviridae | Human Papilloma Virus 1, 6, 11, 16, 52, 58, Cottontail rabbit Papillomavirus, bovine papilloma virus 1,2, 4 |

| Picornaviridae | Enterovirus D68, Enterovirus 71 and Coxsackievirus A6, A10 and A16, Poliovirus type I |

| Nodaviridae | Redspotted grouper nervous necrosis virus, Nervous necrosis virus |

| Parvoviridae | Porcine parvovirus, Adeno associated virus, Human Parvovirus 4, B19, Human bocaviruses |

| Paramyxoviridae | Sendai virus, Tioman virus, Human parainfluenza virus 2 and 4, Menangle virus, Nipah virus |

| Circoviridae | Porcine circovirus |

| Retroviridae | HIV |

| Kolmioviridae | Hepatitis Delta Virus |

| Fiersviridae | Cacteriophage Qbeta virus |

| Sedoreoviridae | Rotavirus |

| Potyviridae | Johnsongrass mosaic virus |

| Polyomaviridae | Human polyoma virus, hamster polyoma virus, bird polyomavirus, Goose hemorrhagic, Polyomavirus |

| Caliciviridae | Norovirus, Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus |

| Bromoviridae | Cowpea chlorotic mottle virus |

| Birnaviridae | Infectious bursal disease virus |

| Secoviridae | Grapevine fanleaf virus |

| Togaviridae | Chikungunya virus |

| Iridoviridae | Chinese Giant Salamander iridovirus |

2. Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Although VLP production in S. cerevisiae has several success stories, some drawbacks are still ongoing. First of all S. cerevisiae has a lower efficiency than other yeasts, including H. polymorpha and P. pastoris, to secrete heterologous proteins [17], so all viral proteins are expressed intracellularly in relatively large amounts; this means that they can potentially produce misfolded aggregates that could be toxic for the yeast cells and consequently reduce VLP yield. Additionally, S. cerevisiae is unsuitable for high-density culture. This depends on its particular metabolism. The preferred carbon source of S. cerevisiae is glucose metabolized mainly by fermentation with ethanol production. This is because S. cerevisiae exhibits the so-called Crabtree effect: alcoholic fermentation in the presence of oxygen when the glucose concentration exceeds a certain threshold value, even under aerobic conditions. When the glucose concentration is restrictive, ethanol produced during fermentation is used as a carbon source, by a shift to a respiration mode. The shift from one carbon source to another, known as a diauxic shift, determines a growth slowdown necessary to adapt to the alternate carbon source [18]. Another limitation of using S. cerevisiae is the pattern of protein glycosylation that is different from mammalian cells. In this microorganism, N-glycosylation leads to hyper-mannosylated N-glycans (more than 100 mannose residues) and allergenic molecules because of the terminally added mannose attached by an α1,3 bond [19]. Synthetic biology, which has been focusing on the engineering of S. cerevisiae, could help to improve or optimize the expression level of viral proteins. Currently, many toolkits are commercially available to standardize methods and protocols in S. cerevisiae and other yeasts [20].

3. Pichia pastoris

The expression of heterologous proteins in P. pastoris leads to a higher yield of the protein in comparison to other yeasts, including S. cerevisiae. P. pastoris can grow to densities as high as 130 g/L of dry cell weight enabling the production of grams per liter of heterologous proteins [21]. Unlike S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris is a Crabtree-negative yeast, meaning that it metabolizes glucose by complete oxidation to carbon dioxide and water. P. pastoris is a methylotrophic yeast, because it can utilize methanol as its sole carbon and energy source. The first step of the methanol metabolism pathway is methanol oxidation by the enzyme alcohol oxidase (AOX) leading to the production of formaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide. In P. pastoris, two genes code for AOX: AOX1 and AOX2. Specifically, AOX1 is responsible for most of this activity and is expressed only in the presence of methanol as the sole carbon source and repressed by glucose. GAL1 expression in S. cerevisiae is induced by galactose and repressed by glucose, although a low level of expression occurs also in the presence of glucose. Most VPLs produced in P. pastoris are expressed under the control of pAOX1 [4]. Methylotrophic yeasts possess the capacity to secrete large quantities of correctly folded proteins. Secretion is an important step in VLP production because it simplifies purification, avoiding cell lysis, denaturation, and refolding of proteins. Secretion occurs also in other yeast species, but the advantage of P. pastoris is that it does not secrete proteases and only few endogenous proteins are released in the medium, thus facilitating subsequent purification. Moreover, comparing P. pastoris and mammalian genomes, the secretory pathway of P. pastoris resembles that of mammalian cells. This observation has been confirmed by structural analysis of Golgi apparatus, which, in this yeast species, is arranged in stacks and surrounded by a matrix that seems to fuse cisternae, as observed in mammalian and plant cells [22]. By contrast, in S. cerevisiae, Golgi cisternae do not stack and are individually scattered in the cytoplasm. One of the most frequently used secretion signals is the N-terminal portion of the pre-pro α-factor from S. cerevisiae. A success story of VLP secretion in P. pastoris is that of Norovirus (NoV) main structural protein VP1. VP1 was successfully expressed and secreted using the methanol-inducible promoter and the α-factor for secretion. NoV VLPs, purified directly from the culture medium, resulted in a total yield greater than 0.6 g/L, with a final purity product over 90%, and are capable of binding the Histo-Blood Group Antigen (HBGA) [23]. Compared to S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris has a shorter and less immunogenic glycosylation pattern, and for this reason is preferred over S. cerevisiae as a platform for producing glycosylated proteins. Several glycosylated VLPs have been produced in P. pastoris. The E protein forming the capsid of the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is a 53 kDa protein containing a single potential carbohydrate attachment site. When expressed in P. pastoris for VLP production, it was secreted as a glycosylated protein and able to stimulate immune responses that protected mice against JEV infection [24]. Glycosylated VLPs inducing a potent immune response in mice were produced in P. pastoris for hepatitis E virus (HEV) [25]. The glycosylated envelope protein prE of several Dengue virus serotypes forms VLPs in P. pastoris and induces an immune response in mice [26][27][28][29] .

4.Hansenula polymorpha

Hansenula polymorpha (Pichia angusta) belongs to the facultative methylotrophic yeast species group. Compared to P. pastoris, H. polymorpha is thermotolerant: the optimal growth temperature is 37–42 °C. Growth at high temperatures can both reduce the contamination risk and promote the production of proteins requiring a temperature of 37 °C to maintain their biological activity [30].

As for other yeast species, the genome of H. polymorpha has been completely sequenced and several strong promoters have been identified and characterized, including strong methanol-inducible promoters of genes such as formate dehydrogenase (pFMD), methanol oxidase (pMOX), and dihydroxyacetone synthase (pDHAS or pDAS), which control the expression of enzymes belonging to the methanol utilization pathway. The shift from glucose to methanol causes the induction of the expression of these genes and the downregulation of those belonging to the glycolytic pathway. Notably, after 2 h of growth in methanol, pFMD is 347-fold upregulated (while pDHAS is 17.3-fold) compared to glucose growth [31]. This kind of promoter can be de-repressed by glycerol and, to a lower extent, by other carbon sources, while in P. pastoris the pAOX1/2 are not de-repressed but induced by methanol. Additionally, pMOX of H. polymorpha is also induced in a medium containing both methanol and glycerol [32]. Various genetic engineering tools and transformation protocols are well-established in H. polymorpha. The use of nanoscale carriers for DNA delivery is the most efficient method for H. polymorpha transformation [33], although other techniques are also widely used, such as the lithium acetate-dimethyl sulfoxide method [34] and electroporation (with the linearized vector) [35]. Contrary to S. cerevisiae, episomal plasmids are unstable in H. polymorpha, even when containing the H. polymorpha autonomous replicating sequences (HARS) for the autonomous replication of the circular plasmids so integration plasmids are the most commonly used tool for the expression of VLP proteins [36]. Concerning post-translational modifications, N-glycans derived from H. polymorpha are similar to those of P. pastoris described in the previous paragraph and thereby are less hyper-mannosylated than the N-glycans produced by S. cerevisiae [37]. VLPs composed of glycosylated proteins have been effectively produced in H. polymorpha [4]. In the last decade, H. polymorpha has been widely studied for VLP production, leading to FDA-licensed and commercially available vaccines for HBV such as Hepavax-Gene® and Heplisav-B® .

As for the other yeast species, the bottleneck in producing VLPs is the purification method because viral proteins accumulate intracellularly [38]. H. polymorpha can be engineered to modulate the ER folding environment and, therefore, to secrete a heterologous protein by overexpression of calnexin[39], a key component of the quality control mechanism in the ER, or by the leader sequence of the α-factor [40]. However, secretion approaches must be further characterized, and these results could inspire further studies for the set-up of engineered H. polymorpha that can secrete the viral proteins for VLP assembly in the growth medium.

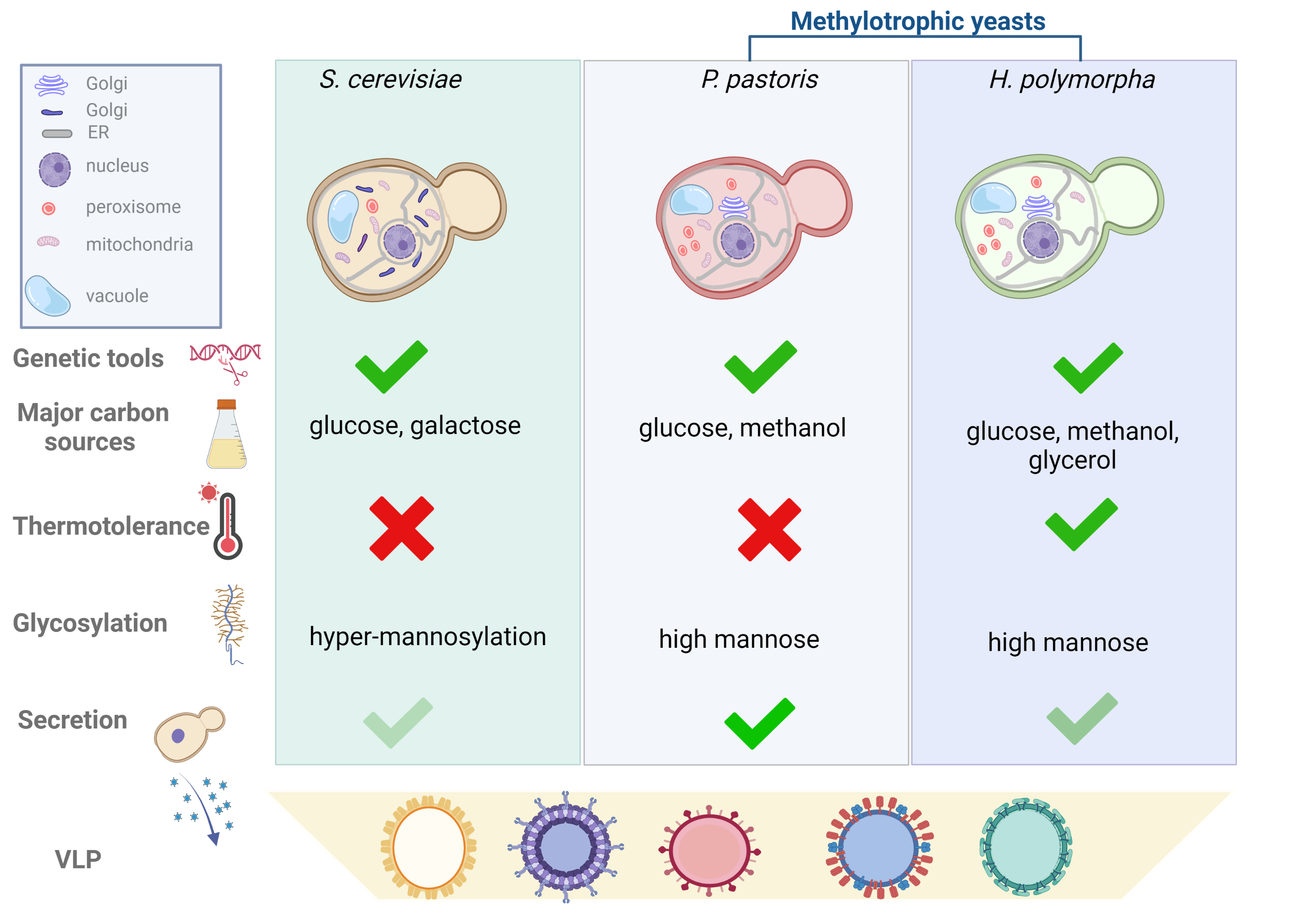

In Figure 1, the researchers compare the key features to consider when planning a platform for VLP production for the three species.

Figure 1. Comparison of yeast manipulation tools, features and parameters to be considered for the selection of the yeast species for VLPs production. Yeast cells of S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris and H. polymorpha are represented with the organelles to highlight the structural differences. Golgi apparatus of S. cerevisiae is organized in cisternae scattered throughout the cytoplasm; while in methylotrophic yeasts, Golgi apparatus is organized in stacked cisternae dispersed in the cytoplasm resembling those of mammalian cells. Methylotrophic yeasts are represented with a higher number of peroxisomes than S. cerevisiae to highlight their increase during growth in presence of methanol. Genetic tools such as mutant strains, plasmids, glycosylation humanized strains are developed for the three species. Carbon sources indicated in the figure are those preferentially used for heterologous protein expression; thermotolerance is referred to the ability to grow at temperature over 30°C. Hyper-mannosylation of proteins observed in S. cerevisiae means that the mannose chain is composed of more than 100 residues. Secretion in the culture medium, although occurring in the three species, has been harnessed mainly in P. pastoris. Created with BioRender.com.

References

- Vieira Gomes, A.M.; Souza Carmo, T.; Silva Carvalho, L.; Mendonca Bahia, F.; Parachin, N.S. Comparison of Yeasts as Hosts for Recombinant Protein Production. Microorganisms 2018, 29, 38.

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, P. Yeast-based vaccines: New perspective in vaccine development and application. FEMS Yeast Res. 2019, 19, foz007.

- Qian, C.; Liu, X.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, T.; Zheng, Q.; Yu, H.; Gu, Y.; Li, S.; et al. Recent Progress on the Versatility of Virus-Like Particles. Vaccines 2020, 8, 139.

- Srivastava, V.; Nand, K.N.; Ahmad, A.; Kumar, R. Yeast-Based Virus-like Particles as an Emerging Platform for Vaccine Development and Delivery. Vaccines 2023, 11, 479.

- Thomas Gassler; Lina Heistinger; Diethard Mattanovich; Brigitte Gasser; Roland Prielhofer. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Homology-Directed Genome Editing in Pichia pastoris; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2019; pp. 211-225.

- Marian F. Laughery; John J. Wyrick; Simple CRISPR‐Cas9 Genome Editing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2019, 129, e110-e110.

- Minori Numamoto; Hiromi Maekawa; Yoshinobu Kaneko; Efficient genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 with a tRNA-sgRNA fusion in the methylotrophic yeast Ogataea polymorpha. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2017, 124, 487-492.

- Aravind Madhavan, K. B. Arun, Raveendran Sindhu, Jayaram Krishnamoorthy, R. Reshmy, Ranjna Sirohi, Arivalagan Pugazhendi, Mukesh Kumar Awasthi, George Szakacs & Parameswaran Binod Customized yeast cell factories for biopharmaceuticals: from cell engineering to process scale up. Microbial Cell Factories 2021, 20, Article number: 124 .

- Robert Gnügge; Fabian Rudolf; Saccharomyces cerevisiaeShuttle vectors. Yeast 2017, 34, 205-221.

- Pablo Valenzuela; Angelica Medina; William J. Rutter; Gustav Ammerer; Benjamin D. Hall; Synthesis and assembly of hepatitis B virus surface antigen particles in yeast. Nat. 1982, 298, 347-350.

- Andris Zeltins; Construction and Characterization of Virus-Like Particles: A Review. Mol. Biotechnol. 2012, 53, 92-107.

- H.J. Kim; Yeast as an expression system for producing virus-like particles: what factors do we need to consider?. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 64, 111-123.

- Sayuri Sakuragi; Toshiyuki Goto; Kouichi Sano; Yuko Morikawa; HIV type 1 Gag virus-like particle budding from spheroplasts of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. null 2002, 99, 7956-7961.

- Saumyabrata Mazumder; Ruchir Rastogi; Avinash Undale; Kajal Arora; Nupur Mehrotra Arora; Biswa Pratim; Dilip Kumar; Abyson Joseph; Bhupesh Mali; Vidya Bhushan Arya; et al.Sriganesh KalyanaramanAbhishek MukherjeeAditi GuptaSwaroop PotdarSourav Singha RoyDeepak ParasharJeny PaliwalSudhir Kumar SinghAelia NaqviApoorva SrivastavaManglesh Kumar SinghDevanand KumarSarthi BansalSatabdi RautrayManish SainiKshipra JainReeshu GuptaPrabuddha Kumar Kundu PRAK-03202: A triple antigen virus-like particle vaccine candidate against SARS CoV-2. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08124.

- Ana Backovic; Tiziana Cervelli; Alessandra Salvetti; Lorena Zentilin; Mauro Giacca; Alvaro Galli; Capsid protein expression and adeno-associated virus like particles assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb. Cell Factories 2012, 11, 124-124.

- Daniel Barajas; Juan Jose Aponte-Ubillus; Hassibullah Akeefe; Tomas Cinek; Joseph Peltier; Daniel Gold; Generation of infectious recombinant Adeno-associated virus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0173010.

- Anh-Minh Tran; Thanh-Thao Nguyen; Cong-Thuan Nguyen; Xuan-Mai Huynh-Thi; Cao-Tri Nguyen; Minh-Thuong Trinh; Linh-Thuoc Tran; Stephanie P. Cartwright; Roslyn M. Bill; Hieu Tran-Van; et al. Pichia pastoris versus Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a case study on the recombinant production of human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 1-8.

- Bernard Turcotte; Xiao Bei Liang; François Robert; Nitnipa Soontorngun; Transcriptional regulation of nonfermentable carbon utilization in budding yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 10, 2-13.

- Stephen R. Hamilton; Piotr Bobrowicz; Beata Bobrowicz; Robert C. Davidson; Huijuan Li; Teresa Mitchell; Juergen H. Nett; Sebastian Rausch; Terrance A. Stadheim; Harry Wischnewski; et al.Stefan WildtTillman U. Gerngross Production of Complex Human Glycoproteins in Yeast. Sci. 2003, 301, 1244-1246.

- Koray Malcı; Emma Watts; Tania Michelle Roberts; Jamie Yam Auxillos; Behnaz Nowrouzi; Heloísa Oss Boll; Cibele Zolnier Sousa Do Nascimento; Andreas Andreou; Peter Vegh; Sophie Donovan; et al.Rennos FragkoudisSven PankeEdward WallaceAlistair ElfickLeonardo Rios-Solis Standardization of Synthetic Biology Tools and Assembly Methods for Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Emerging Yeast Species. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 2527-2547.

- Joan Lin Cereghino; James M. Cregg; Heterologous protein expression in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 24, 45-66.

- Marizela Delic; Minoska Valli; Alexandra B. Graf; Martin Pfeffer; Diethard Mattanovich; Brigitte Gasser; The secretory pathway: exploring yeast diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 872-914.

- Jaime Tomé-Amat; Lauren Fleischer; Stephanie A Parker; Cameron L Bardliving; Carl A Batt; Secreted production of assembled Norovirus virus-like particles from Pichia pastoris. Microb. Cell Factories 2014, 13, 1-9.

- Woo-Taeg Kwon; Protective Immunity of Pichia pastoris-Expressed Recombinant Envelope Protein of Japanese Encephalitis Virus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 22, 1580-1587.

- Jyoti Gupta; Sheetal Kaul; Akriti Srivastava; Neha Kaushik; Sukanya Ghosh; Chandresh Sharma; Gaurav Batra; Manidipa Banerjee; Shalimar; Baibaswata Nayak; et al.C. T. Ranjith-KumarMilan Surjit Expression, Purification and Characterization of the Hepatitis E Virus Like-Particles in the Pichia pastoris. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 141.

- Ankur Poddar; Viswanathan Ramasamy; Rahul Shukla; Ravi Kant Rajpoot; Upasana Arora; Swatantra K. Jain; Sathyamangalam Swaminathan; Navin Khanna; Virus-like particles derived from Pichia pastoris-expressed dengue virus type 1 glycoprotein elicit homotypic virus-neutralizing envelope domain III-directed antibodies. BMC Biotechnol. 2016, 16, 1-10.

- Shailendra Mani; Lav Tripathi; Rajendra Raut; Poornima Tyagi; Upasana Arora; Tarani Barman; Ruchi Sood; Alka Galav; Wahala Wahala; Aravinda de Silva; et al.Sathyamangalam SwaminathanNavin Khanna Pichia pastoris-Expressed Dengue 2 Envelope Forms Virus-Like Particles without Pre-Membrane Protein and Induces High Titer Neutralizing Antibodies. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e64595.

- Lav Tripathi; Shailendra Mani; Rajendra Raut; Ankur Poddar; Poornima Tyagi; Upasana Arora; Aravinda de Silva; Sathyamangalam Swaminathan; Navin Khanna; Pichia pastoris-expressed dengue 3 envelope-based virus-like particles elicit predominantly domain III-focused high titer neutralizing antibodies. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1005.

- Niyati Khetarpal; Rahul Shukla; Ravi Kant Rajpoot; Ankur Poddar; Meena Pal; Sathyamangalam Swaminathan; Upasana Arora; Navin Khanna; Recombinant Dengue Virus 4 Envelope Glycoprotein Virus-Like Particles Derived from Pichia pastoris are Capable of Eliciting Homotypic Domain III-Directed Neutralizing Antibodies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 96, 126-134.

- João Manfrão-Netto; Antônio Milton Vieira Gomes; Nádia Skorupa Parachin; Advances in Using Hansenula polymorpha as Chassis for Recombinant Protein Production. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 94.

- Tim van Zutphen; Richard Js Baerends; Kim A Susanna; Anne de Jong; Oscar P Kuipers; Marten Veenhuis; Ida J van der Klei; Adaptation of Hansenula polymorpha to methanol: a transcriptome analysis. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 1-1.

- Franz S Hartner; Anton Glieder; Regulation of methanol utilisation pathway genes in yeasts. Microb. Cell Factories 2006, 5, 39-39.

- Yevhen Filyak; Nataliya Finiuk; Nataliya Mitina; Oksana Bilyk; Vladimir Titorenko; Olesya Hrydzhuk; Alexander Zaichenko; Rostyslav Stoika; A novel method for genetic transformation of yeast cells using oligoelectrolyte polymeric nanoscale carriers. Biotech. 2013, 54, 35-43.

- Hyunah Kim; Eun Jung Thak; Dong-Jik Lee; Michael O. Agaphonov; Hyun Ah Kang; Hansenula polymorpha Pmt4p Plays Critical Roles in O-Mannosylation of Surface Membrane Proteins and Participates in Heteromeric Complex Formation. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0129914.

- Klaas Nico Faber; Peter Haima; Wim Harder; Marten Veenhuis; Geert AB; Highly-efficient electrotransformation of the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Curr. Genet. 1994, 25, 305-310.

- J H Sohn; E S Choi; C H Kim; M O Agaphonov; M D Ter-Avanesyan; J S Rhee; S K Rhee; A novel autonomously replicating sequence (ARS) for multiple integration in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha DL-1. J. Bacteriol. 1996, 178, 4420-4428.

- Moo Woong Kim; Sang Ki Rhee; Jeong-Yoon Kim; Yoh-Ichi Shimma; Yasunori Chiba; Yoshifumi Jigami; Hyun Ah Kang; Characterization of N-linked oligosaccharides assembled on secretory recombinant glucose oxidase and cell wall mannoproteins from the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Glycobiol. 2003, 14, 243-251.

- Eric Lorent; Horst Bierau; Yves Engelborghs; Gert Verheyden; Fons Bosman; Structural characterisation of the hepatitis C envelope glycoprotein E1 ectodomain derived from a mammalian and a yeast expression system. Vaccine 2008, 26, 399-410.

- Qian, W.; Aguilar, F.; Wang, T.; Qiu, B. Secretion of truncated recombinant rabies virus glycoprotein with preserved antigenic properties using a co-expression system in Hansenula polymorpha. J. Microbiol. 2013, 51 , 234–240. .

- Manal Moussa; Mahmoud Ibrahim; Maria El Ghazaly; Jan Rohde; Stefan Gnoth; Andreas Anton; Frank Kensy; Frank Mueller; Expression of recombinant staphylokinase in the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. BMC Biotechnol. 2012, 12, 96-96.