Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rong Cai | -- | 1171 | 2023-07-29 03:41:22 | | | |

| 2 | Wendy Huang | Meta information modification | 1171 | 2023-07-31 08:43:39 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Zhang, R.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, Q.; Cai, R. Iron Metabolism and Mechanisms of Ferroptosis. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47401 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Zhang R, Chen J, Wang S, Zhang W, Zheng Q, Cai R. Iron Metabolism and Mechanisms of Ferroptosis. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47401. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Zhang, Rongyu, Jinghong Chen, Saiyang Wang, Wenlong Zhang, Quan Zheng, Rong Cai. "Iron Metabolism and Mechanisms of Ferroptosis" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47401 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Zhang, R., Chen, J., Wang, S., Zhang, W., Zheng, Q., & Cai, R. (2023, July 29). Iron Metabolism and Mechanisms of Ferroptosis. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47401

Zhang, Rongyu, et al. "Iron Metabolism and Mechanisms of Ferroptosis." Encyclopedia. Web. 29 July, 2023.

Copy Citation

Ferroptosis is a newly discovered iron-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by phospholipid peroxidation and associated with processes including iron overload, lipid peroxidation, and dysfunction of cellular antioxidant systems. Ferroptosis is found to be closely related to many diseases, including cancer at every stage. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in malignant tumors that originate from epithelia promotes cancer-cell migration, invasion, and metastasis by disrupting cell–cell and cell–cell matrix junctions, cell polarity, etc.

ferroptosis

cancer

iron metabolism

iron overload

lipid peroxidation

1. Brief Description of Iron Metabolism

Although only a trace element, iron plays an essential role in cellular metabolic processes. Iron is present in many forms in the diet and absorbed in the intestine. The most well-known way of absorption is in the form of nonheme iron [1]. Fe3+ in food is, at first, reduced to Fe2+ by duodenal cytochrome B and possibly other reducing enzymes and then crosses the brush border of enterocytes via divalent metal-ion transporter 1 (DMIT1). Enterocyte iron is exported to the blood via ferroportin 1 (FPN1) on the basolateral membrane. Ferroxidase hephaestin on the basolateral membrane oxidizes Fe2+ to Fe3+ so that it binds to plasma transferrin (TF) and is distributed throughout the body in the form of transferrin–iron complexes. When iron-loaded TF binds to transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) on the cell plasma membrane, cells can take up iron by endocytosis. In addition, iron in diets can also be absorbed in the form of heme iron, mainly found in hemoglobin and myoglobin. However, the mechanism of heme iron absorption needs yet to be further investigated [2].

Iron uptake is essential for many key biological processes, such as oxygen transport, DNA replication, and mitochondrial function, etc. A large fraction of intracellular iron enters the mitochondria and is stored or used for the synthesis of heme and iron–sulfur clusters [3]. Heme is engaged in oxygen transport while iron–sulfur clusters are involved in electron transfer in the respiratory chain and act as cofactors for many other proteins required for critical cellular activities. The iron that is not utilized at once is stored in ferritin in an ion state and can be mobilized by ferritin phagocytosis when needed. On the whole, the intracellular iron content is regulated by the iron regulatory element–iron regulatory protein (IRE-IRP) system, while the whole-body iron supply is primarily regulated by the hepcidin–ferroportin (FPN) axis in response to the body’s iron requirements [4].

Iron is exerted from the body through the sloughing of intestinal epithelial cells, exfoliation of skin cells, and physiologic blood loss due to menstruation or minor trauma to epithelial linings. These are passive pathways that are not regulated by iron levels or factors related to iron homeostasis [5].

2. Mechanisms of Ferroptosis

2.1. Iron Overload

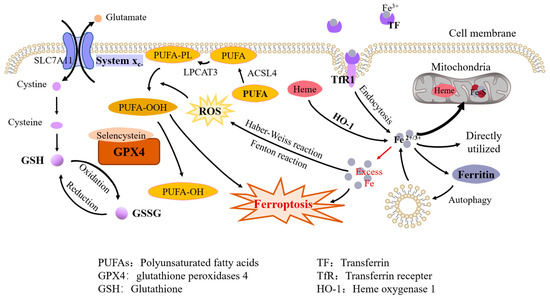

The imbalance of iron metabolism homeostasis results in increased intracellular free iron, which is one of the important features of ferroptosis [6]. Although the specific mechanisms involved in ferroptosis are not yet clear, there is much evidence that ferrous iron plays the critical role in this process (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis. Iron metabolism. Fe3+ is bound to TF and transported in plasma and taken up by endocytosis when iron-loaded TF binds to TfR1 on the cell membrane; intracellular heme and ferritin degradation are also sources of free iron. Intracellular iron is used to synthesize heme and iron–sulfur clusters in the mitochondria, or directly utilized in the cytoplasm, with excess iron being stored in ferritin. Iron overload. Excess iron can lead to ferroptosis directly and it also produces ROS through the Fenton reaction and the Haber–Weiss reaction, which promotes the peroxidation of PUFAs on the cell membrane. Antioxidant system. GPX4 can inhibit ferroptosis by reducing lipid peroxidation and GPX4 containing selenocysteine exhibits increased antiferroptosis activity. GSH is a cofactor of GPX4. Cysteine, an essential constituent of GSH, is transported into cells by system Xc-, which consists of two subunits, SLC7A11 and SLC3A2.

By using iron chelators, Dixon et al. successfully blocked ferroptosis both in vivo and in vitro. They also found that exogenous iron supplementation increased the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis inducers [7]. Hou et al. observed an increase in cellular labile iron during the induction of ferroptosis [8]. Li et al. found that excess iron, both heme and nonheme iron, can directly induce ferroptosis [9]. In addition, excess iron produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) through the Fenton reaction and the Haber–Weiss reaction, triggering oxidative stress and promoting lipid peroxidation through nonenzymatic reactions [10].

Studies about iron metabolism in ferroptosis suggest that key molecules in the process of iron metabolism might all be regulators of cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis [11]. Given that drug-resistant cancer cells are vulnerable to ferroptosis and that a number of organ injuries and degenerative pathologies are driven by ferroptosis, therapeutic ideas targeting ferroptosis might offer a new turnaround for many diseases.

2.2. Lipid Peroxidation

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are susceptible to peroxidation during ferroptosis. The enzymes ACSL4 (Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4) and LPCAT3 (lysophospholipid acyltransferase 3) are closely related to the synthesis of phospholipids containing polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA-PLs) (Figure 1). ACSL4 can cause the enrichment of long PUFAs in cell membranes [12]. LPCAT3 promotes the combination of PUFAs with phospholipids to form PUFA-PLs, which are susceptible to free-radicals-induced oxidation catalyzed by lipoxygenase.

Fatty acid synthesis mediated by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACAC) as well as release mediated by lipophagy induces the accumulation of intracellular free fatty acids, thereby accelerating ferroptosis. AMPK-mediated ACAC phosphorylation inhibits ferroptosis by preventing the synthesis of PUFAs [13].

Normally, several lipoxygenases participate in lipid peroxidation; for example, lipoxygenase-12/15 usually oxidizes PUFAs [14] while inhibition or knockdown of lipoxygenases inhibits ferroptosis in some cell types [15].

2.3. Antioxidant Systems

The glutathione peroxidases (GPX) family is considered to be an important protective system in lipid peroxidation, among which GPX4 plays a key role in inhibiting ferroptosis by reducing phospholipid hydroperoxides to hydroxyphospholipid directly [16]. Drugs that inhibit GPX4 (class II ferroptosis-inducers), such as RSL3, ML162, ML210, can induce ferroptosis [17]. The containing of selenocysteine confers GPX4 increased antiferroptotic activity [18] and GSH as an essential cofactor, helps GPX4 reduce lipid hydroperoxide to lipid alcohols [19].

Cystine/glutamate transporter (also known as system Xc-) transports cystine (Cys2) into cells, which is then oxidized to cysteine (Cys). Cysteine is used to synthesize GSH under the catalysis of glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL) and glutathione synthetase (GSS). System Xc- consists of two subunits, SLC7A11 (solute carrier family 7A member 11) and SLC3A2 (solute carrier family 3A member 11). The expression and activity of SLC7A11 are positively regulated by the transcription factor nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (NRF2) [20] and negatively regulated by p53 [21], which helps to control the level of GSH in ferroptosis (Figure 1). System Xc- inhibitors (class I ferroptosis-inducers), including erastin, sulfasalazine, and sorafenib, can thus induce lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis [17].

The NADPH–FSP1–CoQ10 pathway is another important antioxidant pathway independent from the system Xc–GSH–GPX4 axis. CoQ10 is mainly synthesized in mitochondria and its reduced form, CoQ10H2, is a robust lipophilic antioxidant [22]. FSP1, ferroptosis inhibitor protein 1, is recruited to the plasma membrane to reduce CoQ10 to CoQ10H2, which effectively blocks the spread of lipid peroxides [23].

References

- Fuqua, B.K.; Vulpe, C.D.; Anderson, G.J. Intestinal iron absorption. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2012, 26, 115–119.

- West, A.R.; Oates, P.S. Mechanisms of heme iron absorption: Current questions and controversies. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 4101–4110.

- Dutt, S.; Hamza, I.; Bartnikas, T.B. Molecular Mechanisms of Iron and Heme Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2022, 42, 311–335.

- Mleczko-Sanecka, K.; Silvestri, L. Cell-type-specific insights into iron regulatory processes. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 110–127.

- Koleini, N.; Shapiro, J.S.; Geier, J.; Ardehali, H. Ironing out mechanisms of iron homeostasis and disorders of iron deficiency. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e148671.

- Chen, X.; Yu, C.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Iron Metabolism in Ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 590226.

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072.

- Hou, W.; Xie, Y.; Song, X.; Sun, X.; Lotze, M.T.; Zeh, H.J., 3rd; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy 2016, 12, 1425–1428.

- Li, Q.; Han, X.; Lan, X.; Gao, Y.; Wan, J.; Durham, F.; Cheng, T.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, C.; et al. Inhibition of neuronal ferroptosis protects hemorrhagic brain. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e90777.

- Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Hai, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yue, T. Mechanism and intervention measures of iron side effects on the intestine. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2113–2125.

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 266–282.

- Doll, S.; Proneth, B.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Panzilius, E.; Kobayashi, S.; Ingold, I.; Irmler, M.; Beckers, J.; Aichler, M.; Walch, A.; et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 91–98.

- Lee, H.; Zandkarimi, F.; Zhang, Y.; Meena, J.K.; Kim, J.; Zhuang, L.; Tyagi, S.; Ma, L.; Westbrook, T.F.; Steinberg, G.R.; et al. Energy-stress-mediated AMPK activation inhibits ferroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 225–234.

- Hassannia, B.; Vandenabeele, P.; Vanden Berghe, T. Targeting Ferroptosis to Iron Out Cancer. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 830–849.

- Yang, W.S.; Kim, K.J.; Gaschler, M.M.; Patel, M.; Shchepinov, M.S.; Stockwell, B.R. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4966–E4975.

- Yang, W.S.; SriRamaratnam, R.; Welsch, M.E.; Shimada, K.; Skouta, R.; Viswanathan, V.S.; Cheah, J.H.; Clemons, P.A.; Shamji, A.F.; Clish, C.B.; et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell 2014, 156, 317–331.

- Conrad, M.; Pratt, D.A. The chemical basis of ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 1137–1147.

- Ingold, I.; Berndt, C.; Schmitt, S.; Doll, S.; Poschmann, G.; Buday, K.; Roveri, A.; Peng, X.; Porto Freitas, F.; Seibt, T.; et al. Selenium Utilization by GPX4 Is Required to Prevent Hydroperoxide-Induced Ferroptosis. Cell 2018, 172, 409–422.e21.

- Ursini, F.; Maiorino, M. Lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis: The role of GSH and GPx4. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 152, 175–185.

- Chen, D.; Tavana, O.; Chu, B.; Erber, L.; Chen, Y.; Baer, R.; Gu, W. NRF2 Is a Major Target of ARF in p53-Independent Tumor Suppression. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 224–232.e4.

- Jiang, L.; Kon, N.; Li, T.; Wang, S.-J.; Su, T.; Hibshoosh, H.; Baer, R.; Gu, W. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 2015, 520, 57–62.

- Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Jin, S.; Chen, Y.; Guo, R. Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: A novel approach to reversing drug resistance. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 47.

- Bersuker, K.; Hendricks, J.M.; Li, Z.; Magtanong, L.; Ford, B.; Tang, P.H.; Roberts, M.A.; Tong, B.; Maimone, T.J.; Zoncu, R.; et al. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature 2019, 575, 688–692.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cell Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

681

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

31 Jul 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No