Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Guo Dongwei | -- | 2745 | 2023-07-26 15:13:26 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 2745 | 2023-07-28 05:26:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Guo, D.; Li, Y.; Duan, C.; Fan, C.; Sun, P. Porphyry Mo Deposits. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47315 (accessed on 28 February 2026).

Guo D, Li Y, Duan C, Fan C, Sun P. Porphyry Mo Deposits. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47315. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Guo, Dongwei, Yanhe Li, Chao Duan, Changfu Fan, Pengcheng Sun. "Porphyry Mo Deposits" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47315 (accessed February 28, 2026).

Guo, D., Li, Y., Duan, C., Fan, C., & Sun, P. (2023, July 26). Porphyry Mo Deposits. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47315

Guo, Dongwei, et al. "Porphyry Mo Deposits." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 July, 2023.

Copy Citation

Porphyry Mo deposits are the most important type of Mo resource. They result from a high oxygen fugacity of the parent magma, which acts as an effective indicator for evaluating the mineralization. In the ore-forming system of porphyry Mo deposits, sulfur exists mainly as sulfate in highly oxidized magma but as sulfide in ores. What triggers the reduction in the mineralization system that leads to sulfide precipitation has not yet been determined.

porphyry Mo deposits

high oxygen fugacity

redox state transformation

1. Introduction

Porphyry Mo deposits are an important source of Mo resources. The distribution of Mo resources is uneven globally, with approximately 90% of molybdenum distributed in China, America, Peru, Chile, and Canada [1]. The formation of porphyry molybdenum deposits is closely related to the subduction of the oceanic crust [2]. They have been classified as Climax-type (rift-related, represented by the deposits in the Climax-Henderson Mo belt in America) [3][4][5], Endako-type (arc-related, represented by the Endako and MAX deposits in Canada; Quartz Hill, Thompson Creek, and Buckingham deposits in America; Tamboras deposit in Peru; and deposits in the Gangdese metallogenic belt and the Central Asian orogenic belt in China) [6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18], and Dabie-type (collision-related, typified by deposits in the Qingling-Dabie Mo belt in China) deposits [19][20][21][22][23].

The parent magma of porphyry Mo deposits often contains primitive gypsum, magnetite/hematite, and other highly oxidized minerals, implying a very high oxygen fugacity of the primitive magma [3][4][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31]. The high oxygen fugacity of the initial magma is favorable for chalcophile ore metal elements such as Cu and Mo to enter the magma as incompatible components during partial melting, forming sulfur-rich and Mo-rich ore-forming magma. Furthermore, the high oxygen fugacity makes the sulfur present mainly as sulfate anions, which prevents ore-forming metal elements from precipitating as sulfide in the magma during the migration and evolution of magma [32][33][34]. Therefore, a high oxygen fugacity has become a widely accepted criterion for distinguishing mineralized and nonmineralized porphyries [34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44]. A high fractionation and oxygen fugacity of the parent magma and enrichment of Mo, S, and H2O are favorable conditions for porphyry Mo ore production [45]. However, in some deposits, melts and fluids in mineralization systems have lower Mo contents (2–25 ppm) [30][46][47][48], indicating conditions for the accumulation and efficient unloading of ore-forming materials, which may be more important than the initial Mo concentration of magma [49].

Sulfur exists mainly as sulfate anions in the highly oxidized magma but also as sulfide in ores, indicating significant changes in redox conditions during mineralization. This variation is an essential scientific issue related to the genesis and efficient evaluation of porphyry Mo deposits. However, there is no specific interpretation yet. Li and his coauthors proposed that highly oxidized porphyry with reductive carbonaceous surrounding rocks or Fe-rich volcanic rocks was a new indicator for efficiently evaluating porphyry mineralization [42]. There are two primary reductive surrounding rocks related to porphyry mineralization: carbonaceous surrounding rocks and Fe-rich volcanic rocks [42]. Carbonaceous surrounding rocks are more developed in porphyry Mo deposits in China [22][50][51][52][53][54][55], and Fe-rich volcanic rocks are prevalent in porphyry Mo deposits in South America [56][57][58][59].

2. Geological Characteristics of Porphyry Mo Deposits and Their Relationship with Carbonaceous Surrounding Rocks

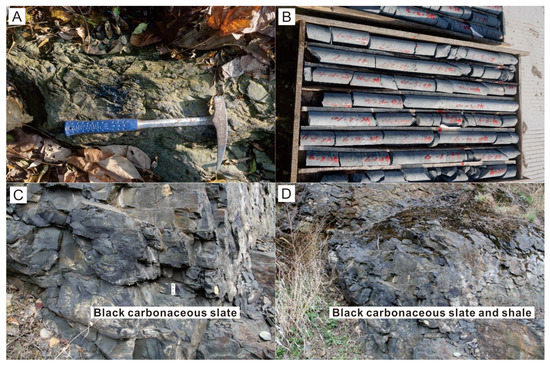

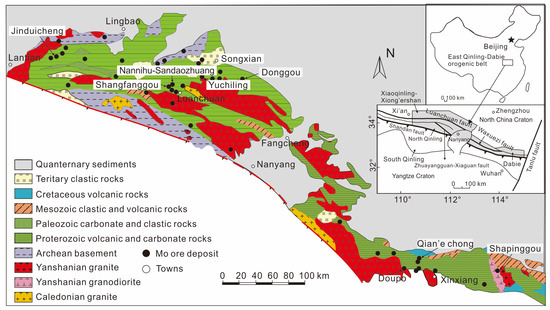

Numerous studies have demonstrated that dark-black reductive carbonaceous sedimentary layers are widely developed in the roof and surrounding rocks of giant or large porphyry Mo deposits, such as the Shuidigou Formation of the Proterozoic Taihua Supergroup and the Xianrenchong Formation of the Proterozoic Luzhenguan Group, which contains graphitic schist and graphite gneiss; the Baishugou, Sanchuan, Nannihu and Meiyaogou Formations of the Neoproterozoic Luanchuan Group, which contains carbonaceous slate and shale developed in the East Qinglin-Dabie Mo mineralization belt (Figure 1) [22][50][51][52][53][54][55][60][61]; and the Cretaceous Mancos Formation and Mesaverde Group, which contains coal and carbonaceous shale and siltstone that are widely distributed in the Climax-Henderson Mo mineralization belt in North America [25][62][63][64][65][66][67]. Carbonaceous sedimentary layers provide reductive agents for the porphyry mineralization system and serve as an ideal natural water-resisting layer, critical factors, and conditions for forming high-grade porphyry Mo ores. The CH4, produced by organic matter pyrolysis or carbonaceous interaction with hydrothermal fluids, triggers a sulfate reduction in highly oxidizing mineralization solutions and subsequent efficient ore precipitation. To further understand the role of carbonaceous surrounding rocks in porphyry mineralization, researchers chose several typical Mo deposits in East Qinling-Dabie and Climax-Henderson, which are the world’s two most extensive Mo mineralization belts, as shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Carbonaceous surrounding rocks are closely related to Mo mineralization in the East Qinling-Dabie Mo mineralization belt. (A) The surface exposure of the Sanhe graphite deposit occurred in the Xianrenchong Formation of the Luzhenguan Group in the periphery of the Shapinggou Mo deposit in Jinzhai. (B) Rock cores from the Sanhe graphite deposit in Xingfu village. (C) The thick-layered black carbonaceous slate of the Baishugou Formation within the boundary of the Nannihu-Sandaozhuang Mo deposits. (D) Black carbonaceous slate and shale of the Baishugou Formation within the boundary of the Nannihu-Sandaozhuang Mo deposits.

2.1. Nannihu-Sandaozhuang-Shangfanggou Mo-(W) Porphyry-Skarn Deposits

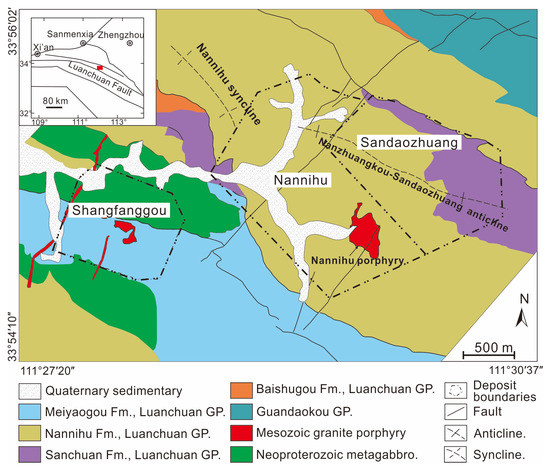

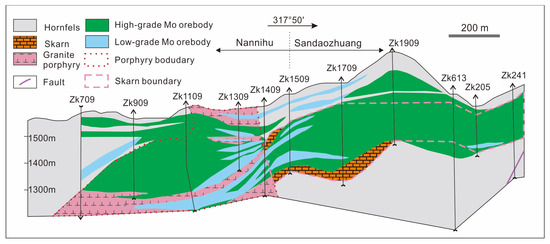

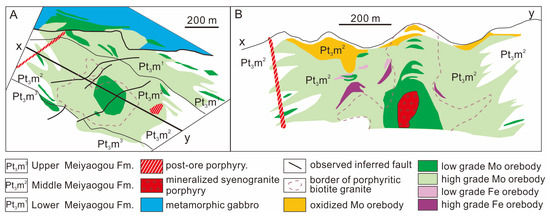

The Luanchuan ore field, which is situated in the western part of the East Qinling-Dabie Mo mineralization belt, includes the Nannihu Mo-(W) porphyry deposit, the Sandaozhuang Mo-(W) skarn deposit, and the Shangfanggou Mo-Fe porphyry deposit (Figure 2 and Figure 3) [50][68]. The total measured Mo reserves are more than 200 × 104 t, with a large W reserve of more than 70 × 104 t [51]. The outcropping strata consist of the Mesoproterozoic Guandaokou Group and the Neoproterozoic Luanchuan Group, comprising the Baishugou, Sanchuan, Nannihu, and Meiyaogou Formations, listed in ascending order. The Yanshanian metallogenic granite porphyry intrudes into the Nannihu Formation and the ore body occurs in the granite porphyry and altered biotite-feldspar hornfels in the Nannihu Mo-(W) porphyry deposit. Similarly, the thick-layered ore body is mainly hosted in the calc-silicate hornfels and the skarns in the upper Sanchuan Formation in the Sandaozhuang Mo-(W) skarn deposit (Figure 4). In the Shangfanggou Mo-Fe deposit, the Mo orebodies occur in the porphyritic biotite granite and its contact zones with the Meiyaogou Formation, including stone coal seams with thicknesses greater than 154 m, as well as in the altered gabbro. The layered Fe ores occur in the contact zone between the granite porphyry and the marble (Figure 5).

Figure 2. Simplified geology and distribution of Mo deposits in the East Qinling–Dabie Mo mineralization belt (after [68]).

Figure 3. Geological map of the Luanchuan Mo field (after [68]).

Figure 4. Geological section along the No. 9 exploration line in the Nannihu-Sandaozhuang W-Mo deposit (after [53]).

Figure 5. Geological map at the 1132 m level (A) and cross-section (B) of the Shangfanggou porphyry Mo deposit (after [27]).

The mineralization process can be divided Into four stages: (1) stage I, characterized by silicification, potassium and skarn alteration, with small amounts of magnetite and molybdenite; (2) stage II, the main Mo mineralization stage, characterized by intense silicification and sericitization, containing numerous quartz–K-feldspar–molybdenite veins, quartz–molybdenite veins and quartz–sulfide veins; (3) stage III, characterized by polymetallic sulfide mineralization, dominated by pyrite veins and quartz-sulfide-carbonate veins; and (4) stage IV, characterized by carbonate veins, quartz–carbonate veins and carbonate–fluorite veins, with almost no sulfides. Mineralization assemblages indicate a gradual decrease followed by an increase in the ore-forming system’s oxygen fugacity from the early to late stage.

The calcite in the Nannihu-Sandaozhuang-Shangfanggou Mo (W) porphyry-skarn deposits exhibits extremely low δ13CV-PDB values (−9.1‰ to −1.6‰, mean of −5.9‰), which are significantly different from those of the sedimentary marine carbonates in the Sanchuan Formation. This indicates that some carbon-enriched 12C originates from the carbonaceous rocks surrounding the deposits [53][55][69]. During ore formation, the δ13CV-PDB values of calcite gradually increase, but its δ18OV-SMOW values gradually decrease [69]. This suggests a decrease in the addition of CH4 from the carbonaceous surrounding rocks and an increase in the amount of atmospheric precipitation from the early to late stages, which is consistent with the redox state transformation revealed by mineral assemblages. During the mineralization process, carbonaceous surrounding rocks undergo thermal decomposition or react with hydrothermal fluids to produce CH4 and CO2, resulting in an increased CO2 concentration and a decreased oxygen fugacity in the ore-forming solutions. Sulfate is reduced to sulfide and combines with Mo2+ and other metallic elements to form much sulfide precipitation.

2.2. Shapinggou Porphyry Mo Deposit

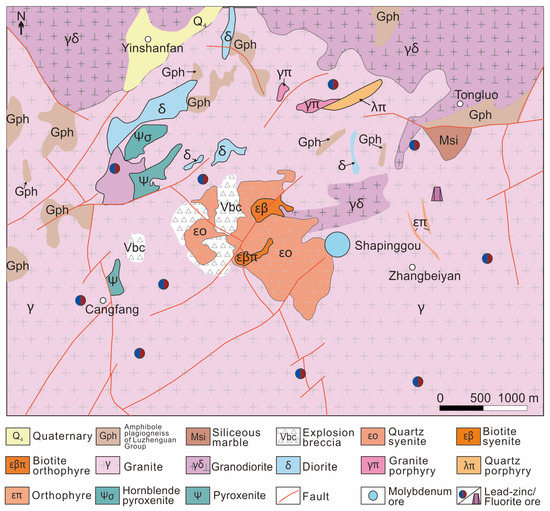

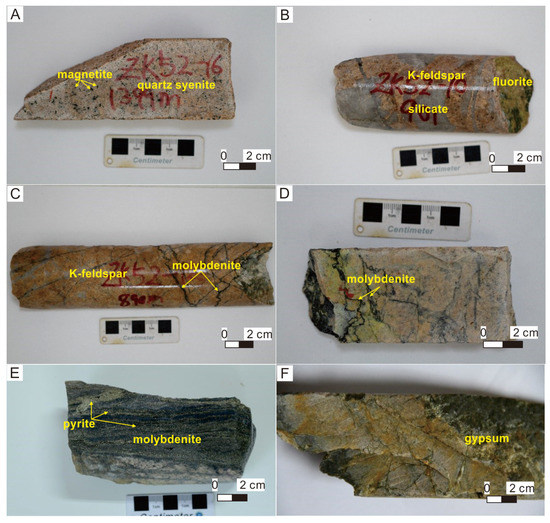

The Shapinggou porphyry Mo deposit is in the eastern Dabie orogenic belt, with a total proven reserve of 1.6 Mt Mo metal, averaging a grade of 0.125% Mo. The main sedimentary layers exposed in this area are metavolcanic and metasedimentary rocks of the Neoproterozoic Luzhenguan Group, which is composed of biotite plagioclase gneiss, monzonite gneiss, plagioclase amphibolite gneiss, variolite, marble, muscovite schists, and graphite schists. Due to intense Yanshanian magmatic activity, the Luzhenguan Group is preserved as residual and captured bodies in the western and northern areas of this region (Figure 6) [70][71][72]. Graphite-mica-quartz schist and graphite-andalusite phyllite in the Xianrenchong Formation of the Luzhenguan Group are enriched to form graphite deposits in Jinzhai-Tiechongxiang-Zaohe (Figure 1A,B). Faults control the cylindric orebodies, which are mainly hosted in the contact zone between the porphyry granite and the surrounding diorite, with scattered orebodies distributed around the area. Lead-zinc and fluorite ores are abundant and encircle the Shapinggou deposit. The deposit shows well-defined alteration zoning of K (Na)-feldspar-quartz, pyrite-sericite-quartz, and chlorite-carbonate from the center granite porphyry outward. The mineralization process can be divided into four stages: (I) K (Na)-feldspar-quartz-magnetite/hematite stage; (II) quartz-K-feldspar-molybdenite stage, which is the main mineralization stage of molybdenite, dominated by quartz-(pyrite)-molybdenite veins in the contact zone between porphyry and surrounding rocks; (III) pyrite-sericite stage, characterized by abundant pyrite, sericitization, and silicification, with weak Mo mineralization; and (IV) quartz-fluorite-gypsum stage, characterized by abundant quartz-fluorite and gypsum veins (Figure 7). The above mineral assemblages indicate that the oxidation state of the mineralizing system gradually decreases from the early stage to the main ore-forming stage, and then increases in the late stage.

Figure 6. Geological map of the Shapinggou Mo deposit (modified from [71]).

Figure 7. Photographs of geological features in the Shapinggou porphyry Mo deposit. (A) Primitive magnetite developed in fresh quartz syenite from deep deposits. (B) Potassium alteration, silicification, and fluoritization from the early to late stages. (C) Potassium alteration and vein of molybdenite mineralization. (D) Sawtooth-shaped molybdenite filled in the fissures. (E) Later disseminated pyrite replaced earlier molybdenite. (F) White gypsum veins filled in the fractures in the late stage.

Due to the regional crustal uplift and erosion, the argillization, propylitic alteration zone, and vein-type Pb–Zn orebodies above the granite porphyry have been completely eroded, whereas the alteration zones and orebodies on both sides of the granite porphyry are preserved. The granite porphyry is now preserved approximately 400 m underground, with its top surface formed at a depth of approximately 2.2 km, and the erosion zone is estimated to be 1.8 km, making the main orebodies approach the surface. Most carbonaceous layers in the Luzhenguan Group in the Shapingou Mo deposit may have been eroded and distributed sporadically as remnants inside and outside the field.

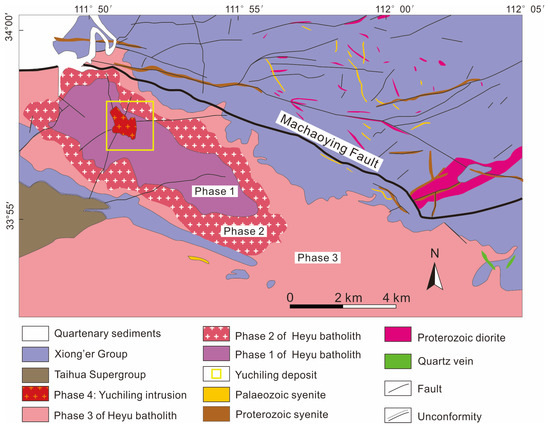

2.3. Yuchiling Porphyry Mo Deposit

The Yuchiling deposit is a giant porphyry Mo deposit located west of the East Qinling–Dabie Mo mineralization belt in Henan Province, China. The main lithostratigraphic units are the Taihua Supergroup (basement) and the Xiong’er Group (cover) (Figure 8) [73]. The Taihua Supergroup, composed of a suite of amphibolite- to granulite-facies metamorphic rocks containing graphite-rich schist, is widely distributed in the Qinling-Dabie metallogenic belt. The carbonaceous sedimentary layers in the Taihua Supergroup, such as the Shuidigou Formation, containing carbonaceous mudstone and limestone, and the Huanchiyu Formation, composed of clastic, argillaceous, carbonaceous dolomitic limestone, and ferrimafic volcanic rocks, have formed graphite deposits in Lushan and Lingbao, respectively [60][61]. The Jidanping Formation and Majiahe Formation of the Xiong’er Group, which are predominantly composed of basaltic andesite, andesite, and dacite, are widely distributed north of the Machaoying Fault.

Figure 8. Geological map of the Yuchiling Mo deposit (after [73]).

The Heyu batholith is a concentrically zoned suite consisting of four nested, texturally distinguishable phases. There are breccia pipes genetically associated with Mo mineralization in the granite intrusion, which contain predominant granulite of the Taihua Supergroup and andesite of the Xiong’er Group. The orebody is mainly hosted in the top and bottom of the breccia and in the surrounding granite and fault zones in the central part of the Heyu batholith and occurs as a thick tabular shape with an average thickness of 178.11 m, showing decreasing grades upward [29][74][75]. The ore-forming processes can generally be divided into three stages: (I) molybdenite-K-feldspar stage, with pervasive potassic alteration and weak Mo mineralization. Fluid inclusions in this stage contain gypsum, hematite, and other highly oxidized minerals, indicating a high oxygen fugacity of fluids rich in SO42−. (II) The quartz-pyrite-molybdenite stage is characterized by veinlets, net veins, and disseminated molybdenite and pyrite (the main mineralization stage). Fluid inclusions contain less SO42− but show the presence of CH4, indicating a lower oxygen fugacity than the previous stage; (III) The quartz–fluorite-calcite stage is characterized by pyritic sericitization with weak mineralization. Fluid inclusions contain CH4 and C2H6, indicating a further decrease in oxygen fugacity during this stage [28][29].

The Yuchiling deposit contains a shallowly buried orebody spanning from 730 to 190 m in elevation. The deposit displays an outcrop of the orebody and the mineralized porphyry, suggesting that it has undergone extensive tectonic uplift and erosion since its formation. The widespread graphite-bearing phyllite of the Taihua Supergroup and volcanic rocks of the Xionger Group, which existed during the formation of the deposit, have been significantly eroded and now exist only in the breccia pipes situated in the southwestern and northeastern parts of the mining area. It is possible that the graphite-bearing phyllite of the Taihua Supergroup may have played a role in the formation of the deposit by providing CH4 as a reductive agent, thereby reducing the oxidized porphyry and efficiently facilitating sulfide precipitation.

2.4. Mt. Emmons Porphyry Mo Deposit

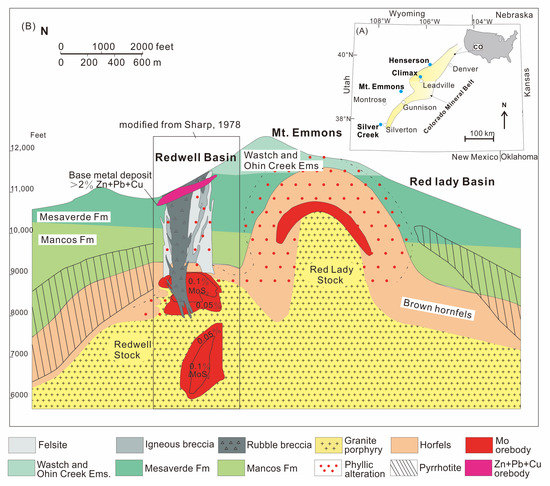

Mt. Emmons lies in the west-central portion of the Colorado (Climax-Henderson) Mo mineralization belt on the eastern coast of the Pacific Ocean. Giant or large Mo deposits, such as the Urad-Henderson, Climax, Mt. Emmons, and Silver Creek deposits, are developed in this belt (Figure 9A). The Mt. Emmons ore field contains two deposits below the Redwell Basin and a third deposit under the Red Lady Basin (Figure 9B). The surrounding sedimentary rocks of the Mancos and Mesaverde Formations consist of dark carbonaceous shale and sandstone beds, which are capped by conglomeratic sandstone beds of the Tertiary Ohio Creek and Wasatch Formations [76]. The granite porphyry stocks intrude the carbonaceous surrounding rocks, forming an altered hornfel contact zone bearing pyrite-pyrrhotite. The black carbonaceous surrounding rocks are altered and discolored, and an innermost 300 m-thick facies of brown hornfels surrounding the stocks grade outward to a 150 m-thick facies of black hornfels [25][77].

The Climax and Urad-Henderson superlarge Mo deposits have geological characteristics and mineralization ages similar to those of the Mt. Emmons deposit. Orebodies occur in the Mesoproterozoic silver plume granite pluton [3][4][78][79]. Previous studies have demonstrated the prevalence of carbonaceous shale, sandstone, mudstone, oil shale, and coal within the Wasatch Formation and the Mesaverde Group in Wyoming and Utah in Colorado [25][62][63][64][65][66][67]. Technically, the mean recoverable gas resources have been estimated at 7 × 1012 m3 with primary sources being coal, carbonaceous shale and siltstone in the Mesaverde Group [80]. In this region, dark carbonaceous shale and mudstone serve as the dominant hydrocarbon sources, providing reductive agents and effective water-resisting layers for mineralization. The absence of carbonaceous sedimentary layers from the Wasatch Formation and Mesaverde Group in the Climax and Urad-Henderson Mo deposits may be attributed to regional crustal uplift and erosion.

Figure 9. (A) Map of Colorado showing the locations of the Urad–Henderson, Mt. Emmons and Silver Creek porphyry Mo deposits and the outlines of the Colorado Mineral Belt; (B) Schematic cross-section through the porphyry Mo deposits in the Redwell Basin and Mt. Emmons, Colorado, in America (modified from [40][46][77]). Black carbonaceous sedimentary layers are widespread in porphyry Mo deposits. Due to tectonic uplift and erosion in some areas, the reductive carbonaceous rocks that once covered the Mo deposits have been completely eroded, such as at the Climax and Urad-Henderson porphyry Mo deposits in America [79]. Carbonaceous rocks may remain only at the periphery of the mining area, such as at the Yuchiling porphyry Mo deposit [73], or appear sporadically in the form of remnants inside and outside the mining area, such as at the Shapinggou porphyry Mo deposit [71]. Notably, the development of reductive components such as graphite ores/coal, dark carbonaceous mudstone/limestone, and natural gas nearby indicates that pre-existing carbonaceous surrounding rocks involved in porphyry Mo mineralization may have been eroded in these deposits. Carbonaceous surrounding rocks provide reductive agents for oxidizing ore-forming fluids and promote sulfate reduction to form Mo and other mineral ores, which is an essential factor for forming large high-grade porphyry Mo deposits.

References

- U.S. Geological Survey. USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries 2023; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2023.

- Sillitoe, R.H. Types of porphyry molybdenum deposits. Min. Mag. 1980, 142, 550–553.

- Seedorff, E.; Marco, T.E. Henderson Porphyry Molybdenum System, Colorado: I. Sequence and Abundance of Hydrothermal Mineral Assemblages, Flow Paths of Evolving Fluids, and Evolutionary Style. Econ. Geol. Bull. Soc. Econ. Geol. 2004, 99, 3–37.

- Seedorff, E.; Marco, T.E. Henderson Porphyry Molybdenum System, Colorado: II. Decoupling of Introduction and Deposition of Metals during Geochemical Evolution of Hydrothermal Fluids. Econ. Geol. Bull. Soc. Econ. Geol. 2004, 99, 39–72.

- Ludington, S.; Plumlee, G.S. Climax-Type Porphyry Molybdenum Deposits; US Geological Survey Open-File Report; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2009; Volume 1215.

- Heintze, L. Geology and Geochemistry of the Porphyry Stockwork Molybdenum Deposit at Tamboras, La Negra Zone (Peru). Econ. Geol. 1985, 80, 2019–2027.

- Linnen, R.L.; Williams-Jones, A.E. Evolution of Aqueous-Carbonic Fluids during Contact Metamorphism, Wall-Rock Alteration, and Molybdenite Deposition at Trout Lake, British Columbia. Econ. Geol. 1990, 85, 1840–1856.

- Carten, R.B.; White, W.H.; Stein, H.J. High-Grade Granite-Related Molybdenum Systems: Classification and Origin; Special Paper; Geological Association of Canada: St. John’s, NL, Canada, 1993; Volume 40, pp. 521–554.

- Selby, D.; Nesbitt, B.E.; Muehlenbachs, K.; Prochaska, W. Hydrothermal Alteration and Fluid Chemistry of the Endako Porphyry Molybdenum Deposit, British Columbia. Econ. Geol. 2000, 95, 183–202.

- Lawley, C.J.M.; Richards, J.P.; Anderson, R.G.; Creaser, R.A.; Heaman, L.M. Geochronology and Geochemistry of the MAX Porphyry Mo Deposit and Its Relationship to Pb-Zn-Ag Mineralization, Kootenay Arc, Southeastern British Columbia, Canada. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 1113–1142.

- Tang, J.X.; Chen, Y.C.; Wang, D.H.; Wang, C.H.; Xu, Y.p.; Qu, W.J.; Huang, W.; Huang, Y. Re-Os Dating of Molybdenite from the Sharang Porphyry Molybdenum Deposit in Gongbógyamda County, Tibet and Its Geological Significance. Acta Geol. Sin. 2009, 5, 698–704.

- Liu, J.; Mao, J.W.; Wu, G.; Wang, F.; Luo, D.F.; Hu, Y.Q. Zircon U-Pb and molybdenite Re-Os dating of the Chalukou porphyry Mo deposit in the northern Great Xing’an Range, China and its geological significance. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2014, 79, 696–709.

- Liu, Y.H.; Ma, R.; Chen, Z.Y.; Gan, Y.Y.; He, F.; Li, X.Z.; Quan, Z.X.; Zhao, Q.X.; Amu, G.L. Geological characteristics and prospecting indicator of Caosiyao Mo deposit, Inner Mongolia. Glob. Geol. 2014, 2, 426–432.

- Wang, G.R.; Wu, G.; Wu, H.; Liu, J.; Li, X.Z.; Xu, L.Q.; Zhang, T.; Quan, Z.X. Fluid inclusion and hydrogen-oxygen isotope study of Caosiyao superlarge porphyry molybdenum deposit in Xinghe County, central Inner Mongolia. Miner. Depos. 2014, 6, 1213–1232.

- Li, H.; Sun, H.S.; Wu, J.H.; Evans, N.J.; Xi, X.S.; Peng, N.L.; Cao, J.Y.; Gabo-Ratio, J.A.S. Re–Os and U–Pb geochronology of the Shazigou Mo polymetallic ore field, Inner Mongolia: Implications for Permian–Triassic mineralization at the northern margin of the North China Craton. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 83, 287–299.

- Sun, H.S.; Li, H.; Danišík, M.; Xia, Q.L.; Jiang, C.L.; Wu, P.; Yang, H.; Fan, Q.R.; Zhu, D.S. U–Pb and Re–Os geochronology and geochemistry of the Donggebi Mo deposit, Eastern Tianshan, NW China: Insights into mineralization and tectonic setting. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 86, 584–599.

- Liao, M.Q.; Lai, Y.; Zhou, Y.T.; Shu, Q.H. Zircon U-Pb Dating and Geochemical Analysis of Ore-Bearing Intrusions of Dasuji Porphyry Mo Deposit. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2018, 54, 763–780.

- Xue, Q.Q.; Zhang, L.P.; Chen, S.; Guo, K.; Li, T.; Han, Z.; Sun, W.D. Tracing black shales in the source of a porphyry Mo deposit using molybdenum isotopes. Geology 2023, 51, 688–692.

- Li, N.; Chen, Y.J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, T.P.; Deng, X.H.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Z.Y. Molybdenum deposits in East Qinling. Earth Sci. Front. 2007, 14, 186–198.

- Chen, Y.J.; Li, N. Nature of ore-fluids of intracontinental intrusion-related hypothermal deposits and its difference from those in island arcs. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2009, 25, 2477–2508.

- Li, C.Y.; Wang, F.Y.; Hao, X.L.; Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Ling, M.X.; Zhou, J.B.; Li, Y.L.; Fan, W.-M.; Sun, W.-D. Formation of the World’s Largest Molybdenum Metallogenic Belt: A Plate-Tectonic Perspective on the Qinling Molybdenum Deposits. Int. Geol. Rev. 2012, 54, 1093–1112.

- Chen, Y.J.; Li, N.; Deng, X.H. Molybdenum Mineralization in Qinling Orogeny; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Shao, Y.; Bala Girei, M.; Jiang, W.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, X. Age, Genesis, and Tectonic Setting of the Qiushuwan Cu–Mo Deposit in East Qinling (Central China): Constraints from Sr–Nd–Hf Isotopes, Zircon U–Pb and Molybdenite Re–Os Dating. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 132, 103998.

- Roedder, E. Fluid Inclusion Studies on the Porphyry-Type Ore Deposits at Bingham, Utah, Butte, Montana, and Climax, Colorado. Econ. Geol. 1971, 66, 98–118.

- Thomas, J.A.; Galey, J.T. Exploration and Geology of the Mt. Emmons Molybdenite Deposits, Gunnison County, Colorado. Econ. Geol. 1982, 77, 1085–1104.

- Yang, Y.F.; Li, N.; Ni, Z.Y. Fluid inclusion study of the Jinduicheng porphyry Mo deposit, Hua country, Shanxi province. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2009, 25, 2983–2993.

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Ore Geology, Fluid Inclusions and Four-Stage Hydrothermal Mineralization of the Shangfanggou Giant Mo–Fe Deposit in Eastern Qinling, Central China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2013, 55, 146–161.

- Zhang, J.; Ye, H.S.; Shi, M.C.; Meng, F. Metallogenic process of the Yuchiling Mo deposit in East Qinling: Constraints from fluid inclusions. Geol. Bull. China 2013, 32, 1113–1128.

- Zhang, J.; Ye, H.S.; Zhou, K.; Meng, F. Processes of Ore Genesis at the World-Class Yuchiling Molybdenum Deposit, Henan Province, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2014, 79, 666–681.

- Audétat, A. Compositional Evolution and Formation Conditions of Magmas and Fluids Related to Porphyry Mo Mineralization at Climax, Colorado. J. Petrol. 2015, 56, 1519–1546.

- Ouyang, H.; Caulfield, J.; Mao, J.; Hu, R. Controls on the Formation of Porphyry Mo Deposits: Insights from Porphyry (-Skarn) Mo Deposits in Northeastern China. Am. Mineral. 2022, 107, 1736–1751.

- Mengason, M.J.; Candela, P.A.; Piccoli, P.M. Molybdenum, Tungsten and Manganese Partitioning in the System Pyrrhotite–Fe–S–O Melt–Rhyolite Melt: Impact of Sulfide Segregation on Arc Magma Evolution. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2011, 75, 7018–7030.

- Chiaradia, M. Copper enrichment in arc magmas controlled by overriding plate thickness. Nat. Geosci. 2014, 7, 43–46.

- Gao, Y.; Yang, Y.C.; Han, S.J.; Meng, F. Geochemistry of Zircon and Apatite from the Mo Ore-Forming Granites in the Dabie Mo Belt, East China: Implications for Petrogenesis and Mineralization. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 126, 103733.

- Sun, W.; Huang, R.; Li, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Sun, S.; Zhang, L.; Ding, X.; Li, C.; Zartman, R.E. Porphyry Deposits and Oxidized Magmas. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 65, 97–131.

- Ballard, J.R.; Palin, M.J.; Campbell, I.H. Relative Oxidation States of Magmas Inferred from Ce(IV)/Ce(III) in Zircon: Application to Porphyry Copper Deposits of Northern Chile. Contrib. Miner. Pet. 2002, 144, 347–364.

- Burnham, A.D.; Berry, A.J. An Experimental Study of Trace Element Partitioning between Zircon and Melt as a Function of Oxygen Fugacity. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 95, 196–212.

- Muñoz, M.; Charrier, R.; Fanning, C.M.; Maksaev, V.; Deckart, K. Zircon trace element and O-Hf isotope analyses of mineralized intrusions from El Teniente ore deposit, Chilean Andes: Constraints on the source and magmatic evolution of porphyry Cu-Mo related magmas. J. Petrol. 2012, 53, 1091–1122.

- Trail, D.; Bruce Watson, E.; Tailby, N.D. Ce and Eu Anomalies in Zircon as Proxies for the Oxidation State of Magmas. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 97, 70–87.

- Zhang, D. Chemistry, Mineralogy and Crystallization Conditions of Porphyry Mo-Forming Magmas at Urad–Henderson and Silver Creek, Colorado, USA. J. Petrol. 2017, 58, 277–296.

- Zhou, T.; Zeng, Q.; Chu, S.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Y. Magmatic Oxygen Fugacities of Porphyry Mo Deposits in the East Xing’an-Mongolian Orogenic Belt (NE China) with Metallogenic Implications. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2018, 165, 145–159.

- Li, Y.H.; Duan, C.; Zeng, P.S.; Jian, W.; Wan, Q.; Hu, G.-Y.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Wu, X.-P. The Role of Reductive Carbonaceous Strata in the Formation of Porphyry Copper Ores. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2020, 41, 637–650.

- Xing, K.; Shu, Q.; Lentz, D.R. Constraints on the Formation of the Giant Daheishan Porphyry Mo Deposit (NE China) from Whole-Rock and Accessory Mineral Geochemistry. J. Petrol. 2021, 62, egab018.

- Xu, L.L.; Bi, X.W.; Zhang, X.C.; Huang, M.L.; Liu, G. Mantle Contribution to the Generation of the Giant Jinduicheng Porphyry Mo Deposit, Central China: New Insights from Combined in-Situ Element and Isotope Compositions of Zircon and Apatite. Chem. Geol. 2023, 616, 121238.

- Jiang, Z.; Shang, L.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Y. An Experimental Investigation into the Partition of Mo between Aqueous Fluids and Felsic Melts: Implications for the Genesis of Porphyry Mo Ore Deposits. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 134, 104144.

- Audétat, A.; Li, W. The Genesis of Climax-Type Porphyry Mo Deposits: Insights from Fluid Inclusions and Melt Inclusions. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 88, 436–460.

- Ouyang, H.; Mao, J.; Hu, R. Geochemistry and Crystallization Conditions of Magmas Related to Porphyry Mo Mineralization in Northeastern China. Econ. Geol. 2020, 115, 79–100.

- Ouyang, H.; Mao, J.; Hu, R.; Caulfield, J.; Zhou, Z. Controls on the metal endowment of porphyry Mo deposits: Insights from the Luming porphyry Mo deposit, Northeastern China. Econ. Geol. 2021, 116, 1711–1735.

- Vigneresse, J.L.; Truche, L.; Richard, A. How Do Metals Escape from Magmas to Form Porphyry-Type Ore Deposits? Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 105, 310–336.

- Li, Y.F.; Mao, J.W.; Hu, H.B.; Guo, B.J.; Bai, F.J. Geology, distribution, types and tectonic settings of Mesozoic molybdenum deposits in East Qinling area. Miner. Depos. 2005, 292–304.

- Ye, H.S.; Mao, J.W.; Li, Y.F.; Yan, C.H.; Guo, B.J.; Zhao, C.S.; Zheng, R.F.; Chen, L. Characteristics and metallogenic mechanism of Mo W and Pb Zn-Ag deposits in Nannihu ore field western Henan province. Geoscience 2006, 81, 165–174.

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.F.; Shi, Y.X. Characteristics of fluid indusions and its geological implication of the Shangfanggou Mo deposit in Luanchuan county, Henan province. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2009, 25, 2563–2574.

- Xiang, J.F.; Pei, R.F.; Ye, H.S.; Wang, C.Y.; Tian, Z.H. New geochronological data of granites and ores from the Nannihu-Sandaozhuang Mo (W) deposit. Geol. China 2012, 39, 1778–1789.

- Yang, Y.F.; Li, N.; Chen, Y.J. Fluid Inclusion Study of the Nannihu Giant Porphyry Mo–W Deposit, Henan Province, China: Implications for the Nature of Porphyry Ore-Fluid Systems Formed in a Continental Collision Setting. Ore Geol. Rev. 2012, 46, 83–94.

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.J.; Deng, X.H. Mineralization Mechanisms in the Shangfanggou Giant Porphyry-Skarn Mo–Fe Deposit of the East Qinling, China: Constraints from H–O–C–S–Pb Isotopes. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 81, 535–547.

- Skewes, M.A.; Holmgren, C.; Stern, C.R. The Donoso Copper-Rich, Tourmaline-Bearing Breccia Pipe in Central Chile: Petrologic, Fluid Inclusion and Stable Isotope Evidence for an Origin from Magmatic Fluids. Min. Depos. 2003, 38, 2–21.

- Cannell, J.; Cooke, D.R.; Walshe, J.L.; Stein, H. Geology, mineralization, alteration, and structural evolution of the El Teniente porphyry Cu-Mo deposit. In Economic Geology and the Bulletin of the Society of Economic Geologists; The Economic Geology Publishing Company: Littleton, CO, USA, 2005; Volume 100, pp. 979–1003.

- Stern, C.R.; Funk, J.A.; Skewes, M.A.; Arevalo, A. Magmatic anhydrite in plutonic rocks at the El Teniente Cu-Mo deposit, Chile, and the role of sulfur and copper-rich magmas in its formation. Econ. Geol. 2007, 102, 1335–1344.

- Vry, V.H.; Wilkinson, J.J.; Seguel, J.; Millan, J. Multistage Intrusion, Brecciation, and Veining at El Teniente, Chile: Evolution of a Nested Porphyry System. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 119–153.

- Chen, Y.J.; Fu, S.G.; Hu, S.X. The main element character and its significance of different type greenstone belts in southern margin of North-China platform. J. Nanjing Univ. 1988, 1, 70–84.

- Ji, H.Z.; Chen, Y.J.; Zhao, Y.Y. Khondalite series and graphite deposits. China Non-Met. Miner. Ind. 1990, 6, 9–11.

- Donnell, J.R. Tertiary Geology and Oil-Shale Resources of the Piceance Creek Basin between the Colorado and White Rivers, Northwestern Colorado; U.S. Geological Survey: Bulletin, WA, USA, 1961; pp. 835–891.

- Roehler, H.W. Vermillion Creek coal bed, high-sulfur, radioactive coal of paludal-lacustrine origin in Wasatch Formation of Vermillion Creek basin, Wyoming and Colorado. AAPG Bull. 1979, 63, 839.

- Roehler, H.W.; Martin, P.L. Geological Investigations of the Vermillion Creek Coal Bed in the Eocene Niland Tongue of the Wasatch Formation, Sweetwater County, Wyoming; U.S. Geological Survey Professional Papers; U.S. Geological Survey: Denver, CO, USA, 1987; p. 1314.

- Sanchez, J.D. Stratigraphic Framework, Coal Zone Correlations, And Depositional Environment of The Upper Cretaceous Blackhawk Formation And Star Point Sandstone in The Scofield And Beaver Creek Areas, Nephi 30’ x 60’ Quadrangle, Wasatch Plateau Coal Field, Carbon County, Utah. Coal Investigations Map; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1990.

- Li, Z.; Schieber, J. Composite Particles in Mudstones: Examples from the Late Cretaceous Tununk Shale Member of the Mancos Shale Formation. J. Sediment. Res. 2018, 88, 1319–1344.

- Collins, B.A. Geology of the Coal-Bearing Mesaverde Formation (Cretaceous), Coal Basin Area, Pitkin Country, Colorado. Master’s Thesis, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO, USA, 2020.

- Mao, J.W.; Pirajno, F.; Xiang, J.F.; Gao, J.J.; Ye, H.S.; Li, Y.F.; Guo, B.J. Mesozoic Molybdenum Deposits in the East Qinling–Dabie Orogenic Belt: Characteristics and Tectonic Settings. Ore Geol. Rev. 2011, 43, 264–293.

- Liu, X.S.; Wu, C.Y.; Huang, B. Origin and evolution of the hydrothermal system in Nannihu-Sandaozhuang molybdenum (tungsten) ore deposit, Luanchuan country, Henan province. Geochimica 1987, 7, 199–207.

- Xu, G.; Tang, Z.L.; Jiao, J.G.; Han, X.B.; Zhong, J.X.; Wei, X.; Qiu, G.L. The Comparative Study on Small Intrusion Type Molybdenum Deposits of Shapingg and Jinduicheng. Northwestern Geol. 2012, 45, 367–369.

- Lu, S.M.; Li, J.S.; Ruan, L.S.; Zhao, L.L.; Huang, F.; Wang, B.H.; Zhang, H.D. The characteristics of stable isotope geochemistry of Shapinggou molybdenum deposit, Anhui province. Geoscience 2019, 33, 262–270.

- Ren, Z.; Zhou, T.-F.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, H.-D. Characteristics of the metallogenic system of the Shapinggou super-large porphyry molybdenum deposit in the Dabie orogenic belt, Anhui Province. Earth Sci. Front. 2020, 27, 353–372.

- Li, N.; Ulrich, T.; Chen, Y.-J.; Thomsen, T.B.; Pease, V.; Pirajno, F. Fluid Evolution of the Yuchiling Porphyry Mo Deposit, East Qinling, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2012, 48, 442–459.

- Li, N.; Chen, Y.J.; Ni, Z.Y.; Hu, H.Z. Characteristics of ore-forming fluids of the Yuchiling porphyry Mo deposit, Songxian country, Henan province, and its geological significance. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2009, 25, 2509–2522.

- Zhou, K.; Ye, H.-S.; Mao, J.-W.; Qu, W.-J.; Zhou, S.-F.; Meng, F.; Gao, Y.-L. Geological characteristics and molybdenite Re—Os isotopic dating of Yuchiling porphyry Mo deposit in western Henan Province. Miner. Depos. 2009, 28, 170–184.

- Lorenz, J.C.; Nadon, G.C. Braided-River Deposits in A Muddy Depositional Setting: The Molina Member of the Wasatch Formation (Paleogene), West-Central Colorado, U.S.A. J. Sediment. Res. 2002, 72, 376–385.

- Sharp, J.E. Cave Peak, a Molybdenum-Mineralized Breccia Pipe Complex in Culberson County, Texas. Econ. Geol. 1979, 74, 517–534.

- Clark, K.F. Stockwork Molybdenum Deposits in the Western Cordillera of North America. Econ. Geol. 1972, 67, 731–758.

- Wallace, S.R.; MacKenzie, W.B.; Blair, R.G.; Muncaster, N.K. Geology of the Urad and Henderson Molybdenite Deposits, Clear Creek County, Colorado, with a Section on a Comparison of These Deposits with Those at Climax, Colorado. Econ. Geol. 1978, 73, 325–368.

- Drake, R.M., II; Schenk, C.J.; Mercier, T.J.; Le, P.A.; Finn, T.M.; Johnson, R.C.; Woodall, C.A.; Gaswirth, S.B.; Marra, K.R.; Pitman, J.K.; et al. Assessment of Undiscovered Continuous Tight-Gas Resources in the Mesaverde Group and Wasatch Formation, Uinta-Piceance Province, Utah and Colorado, 2018; USGS Fact Sheet; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2019.

More

Information

Subjects:

Geology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Jul 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No