| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eugénia Andrade | -- | 799 | 2023-07-24 04:08:46 |

Video Upload Options

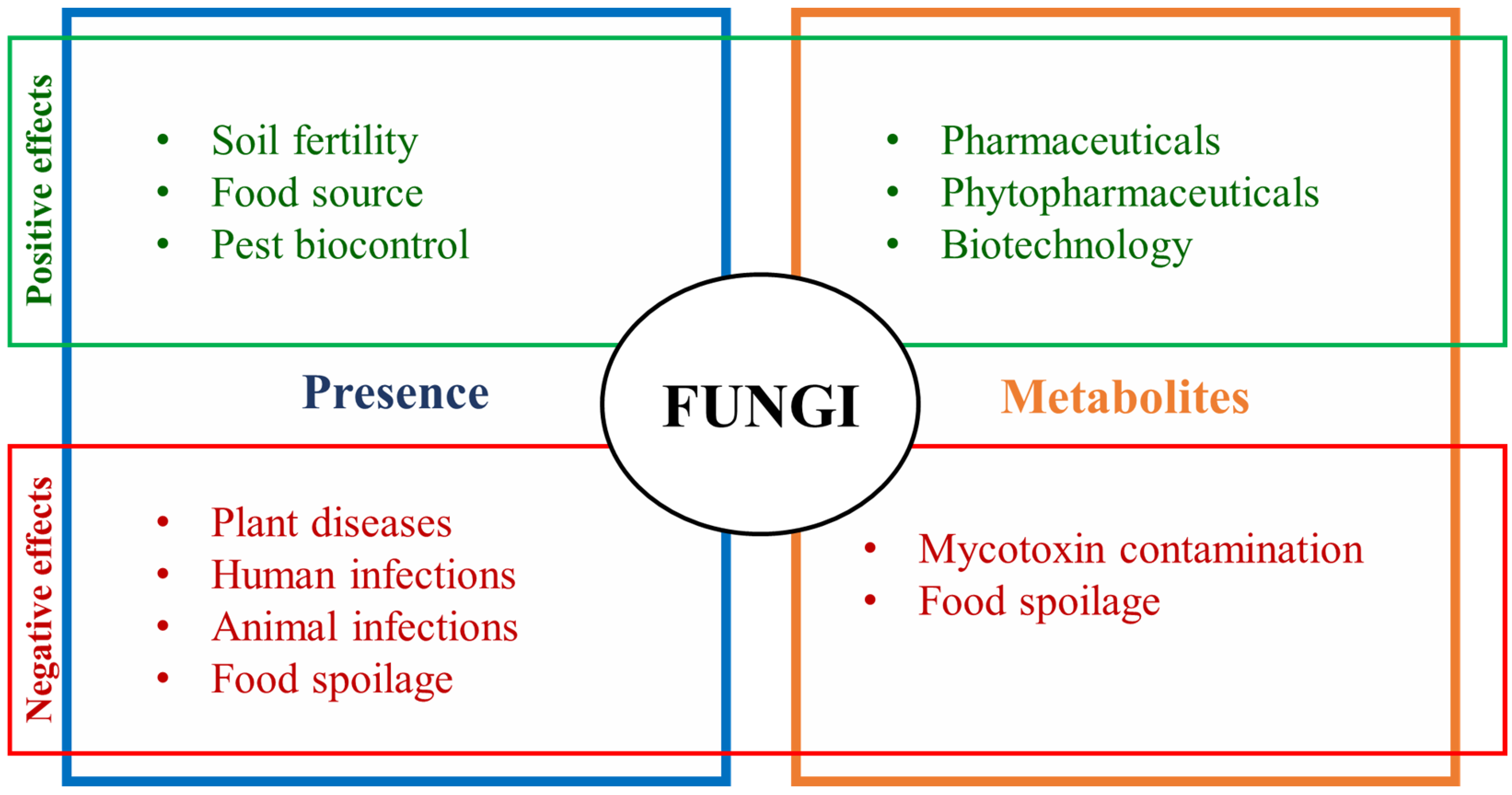

Fungi constitute a diverse group with highly positive and negative impacts in different environments, having several natural roles and beneficial applications in human life, but also causing several concerns. Fungi can affect human health directly, but also indirectly by being detrimental for animal and plant health, influencing food safety and security. Climate changes are also affecting fungal distribution, prevalence, and their impact on different settings. Searching for sustainable solutions to deal with these issues is challenging due to the complex interactions among fungi and agricultural and forestry plants, animal production, environment, and human and animal health. In this way, the “One Health” approach may be useful to obtain some answers since it recognizes that human health is closely connected to animal and plant health, as well as to the shared environment. This review aims to explore and correlate each of those factors influencing human health in this “One Health” perspective. Thus, the impact of fungi on plants, human, and animal health, and the role of the environment as an influencing factor on these elements are discussed.

References

- Blackwell, M. The fungi: 1, 2, 3 ... 5.1 million species? Am. J. Bot. 2011, 98, 426–438.

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Lücking, R. Fungal diversity revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 million species. Fungal Kingd. 2017, 5, 79–95.

- Grossart, H.P.; Van den Wyngaert, S.; Kagami, M.; Wurzbacher, C.; Cunliffe, M.; Rojas-Jimenez, K. Fungi in aquatic ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 339–354.

- Naranjo-Ortiz, M.A.; Gabaldón, T. Fungal evolution: Major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 1443–1476.

- Janowski, D.; Leski, T. Factors in the Distribution of Mycorrhizal and Soil Fungi. Diversity 2022, 14, 1122.

- Daley, D.K.; Brown, K.J.; Badal, S. Chapter 20—Fungal Metabolites. In Pharmacognosy: Fundamentals, Applications and Strategy; Badal, S., Delgoda, R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 413–421. ISBN 9780128020999.

- Esheli, M.; Thissera, B.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Rateb, M.E. Fungal Metabolites in Human Health and Diseases—An Overview. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1590–1601.

- Elmholt, S. Mycotoxins in the Soil Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 167–203.

- Afsah-Hejri, L.; Jinap, S.; Hajeb, P.; Radu, S.; Shakibazadeh, S. A review on mycotoxins in food and feed: Malaysia case study. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 629–651.

- Seyedmousavi, S.; Bosco, S.D.M.G.; De Hoog, S.; Ebel, F.; Elad, D.; Gomes, R.R.; Jacobsen, I.D.; Jensen, H.E.; Martel, A.; Mignon, B.; et al. Fungal infections in animals: A patchwork of different situations. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, 165–187.

- Marín, S.; Ramos, A.J.; Cano-Sancho, G.; Sanchis, V. Reduction of mycotoxins and toxigenic fungi in the mediterranean basin maize chain. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2012, 51, 93–118.

- Vaali, K.; Tuomela, M.; Mannerström, M.; Heinonen, T.; Tuuminen, T. Toxic Indoor Air Is a Potential Risk of Causing Immuno Suppression and Morbidity—A Pilot Study. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 104.

- Kurup, V.P. Fungal allergens. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003, 3, 416–423.

- Bongomin, F.; Gago, S.; Oladele, R.; Denning, D. Global and Multi-National Prevalence of Fungal Diseases—Estimate Precision. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 57.

- Peng, Y.; Li, S.J.; Yan, J.; Tang, Y.; Cheng, J.P.; Gao, A.J.; Yao, X.; Ruan, J.J.; Xu, B.L. Research Progress on Phytopathogenic Fungi and Their Role as Biocontrol Agents. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 670135.

- Simões, D.; Carbas, B.; Soares, A.; Freitas, A.; Silva, A.S.; Brites, C.; de Andrade, E. Assessment of Agricultural Practices for Controlling Fusarium and Mycotoxins Contamination on Maize Grains: Exploratory Study in Maize Farms. Toxins 2023, 15, 136.

- World Health Organization One Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 8 March 2023).