| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dana Mihaela Mihele | -- | 3322 | 2023-07-22 10:34:37 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -1306 word(s) | 2016 | 2023-07-24 02:55:29 | | |

Video Upload Options

Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) is a medical condition recognised relatively recently, over whose definition and inclusion criteria there is still much debate in the literature. Some authors view it as a set of acute and severe systemic symptoms originating in mast cells’ abnormal number or reactivity, with clear laboratory inclusion criteria, while others see it as an immune/inflammatory systemic condition, acute and/or chronic, with manifestations ranging from mild to severe, including anaphylaxis, caused by mediators released from activated mast cells. At present the established diagnostic criteria are still a matter of debate, and there is still no certainty whether cases of MCAS are not missed versus the possibility of over-diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Mast cells (MCs) have received constant attention since their contribution to allergic reaction was uncovered, yet they remain one of the least understood elements of the immune system. Most MC research has focused on their pathological disturbances while their physiological role has been all but ignored. A reader can hardly consult any MC-related article without being told, usually in the first paragraph, that these cells are responsible for potentially lethal IgE-mediated anaphylactic shock. This view of MCs as villains of the immune system has been thus described in a review: “The existence of these potentially hazardous cells has solely been justified due to their beneficial role in some infections with extracellular parasites” [1]. However, a significant body of data, produced largely in the last two decades, has revealed a plethora of functions ranging from defense against infections and toxins to immune surveillance and homeostasis.

In recent years, the term MC activation syndrome (MCAS) was proposed to account for symptoms caused by MC activation, and clear diagnostic criteria have been defined. However, not all authors agree with these criteria, as some find them too restrictive, potentially leaving much of the MC-related pathology unaccounted for.

2. Mast Cells

Mast cells are long-lived, tissue-residing granulocytes that originate in the bone marrow. They share a common myeloid precursor with other granulocytes, including their circulating counterpart, the basophils. Unlike other granulocytes, MCs leave the bone marrow as progenitors fated to complete their maturation in their tissue of residence where they can further expand upon appropriate stimulation [2]. Importantly, they return to baseline numbers in the region of interest when the inflammatory stimulus has subsided [3].

MC tissue distribution follows their role as cells of first defense against potential aggressions. They are present in higher numbers in zones of contact with exogenic antigens, such as skin and cavitary organs. In addition, they concentrate around blood vessels in virtually all tissues [4]. There, MCs are classically activated by IgE antibodies through the high affinity IgE receptors (FcεRIs), which in humans are present on the surface of MCs, basophils and eosinophils [5]. Less efficiently, but probably of greater importance for their function, MCs can be activated through the IgG receptors, cytokines and directly by antigens of invading organisms, the best documented of which are bacteria and parasites [6].

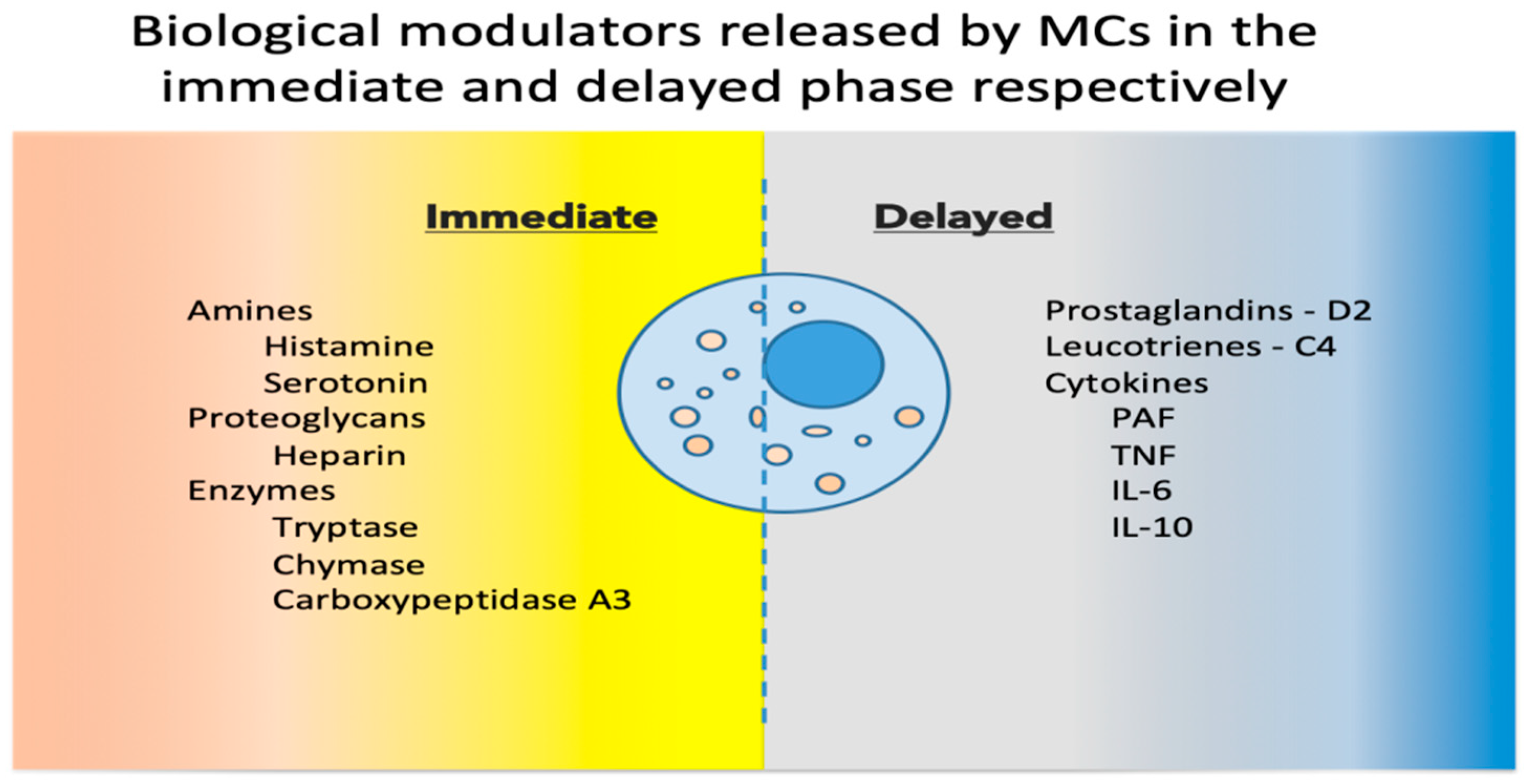

Upon activation, MCs release a host of mediators involved in local defense and homeostasis. Their response has been described as biphasic: immediate—in minutes, preformed mediators are released from granules (degranulation), and delayed—in hours, biological modulators are actively secreted [7]. See Figure 1 for a synthetic list of released and secreted molecules.

Figure 1. Biological modulators released by MCs in the immediate and delayed phases [8][9]. MCs, mast cells; PAF, platelet activating factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin.

As discussed above, MC activation is associated with a significant number of clinical, and even subclinical, conditions and should be expected in any situation where local or systemic inflammation is triggered either acutely or chronically.

3. Mast Cell Activation Syndrome

More than 10 years ago the term MC activation syndrome (MCAS) was proposed for severe systemic MC activation [10]. Since then, this relatively new nosologic entity has come to be viewed as the expression of “aberrant” MC activation [11], as opposed to diseases where MCs are in a greater number than normal, and a group of authors expanded the category of patients to include chronic, mild, but still multi-system symptoms of inflammatory/allergic nature. Some studies even describe a prevalence as high as 17% of the population [12], with 74% of the patients reporting first-degree relatives with similar symptoms.

Since mastocytosis is considered a rare condition, the above prevalence may be viewed as huge. Mastocytosis is a group of disorders characterized by clonal proliferation and accumulation of abnormal MCs in the skin and possibly other organs. Most of the genetic mutations reported to date involve the stem cell factor receptor c-KIT, present on the surface of MCs. The main categories of mastocytosis are cutaneous mastocytosis (CM)—MC proliferation limited to the skin—and systemic mastocytosis (SM)—at least one extracutaneous organ or system involved [13].

MCAS patients usually present a plethora of non-specific complaints, and often associate important comorbid conditions [14]. One has to be prepared to consider their complaints real, before dismissing them as somatizations. Flushing, hypotension (possibly leading to syncope), urticaria, angioedema, wheezing, headache, cramping, vomiting and diarrhea are viewed as typical [13].

The criteria for MCAS were established for the first time in 2012 [15], and continue to be refined by an international consensus group [16]. Although entities like “mast cell activation (disorder), unspecified”, “mast cell activation (syndrome)”, “monoclonal MCAS”, “idiopathic MCAS” and “secondary/reactive MCAS” were recently assigned codes in the United States International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) [16], there is still no certainty as to whether cases of MCAS are not missed versus the possibility of overdiagnosis.

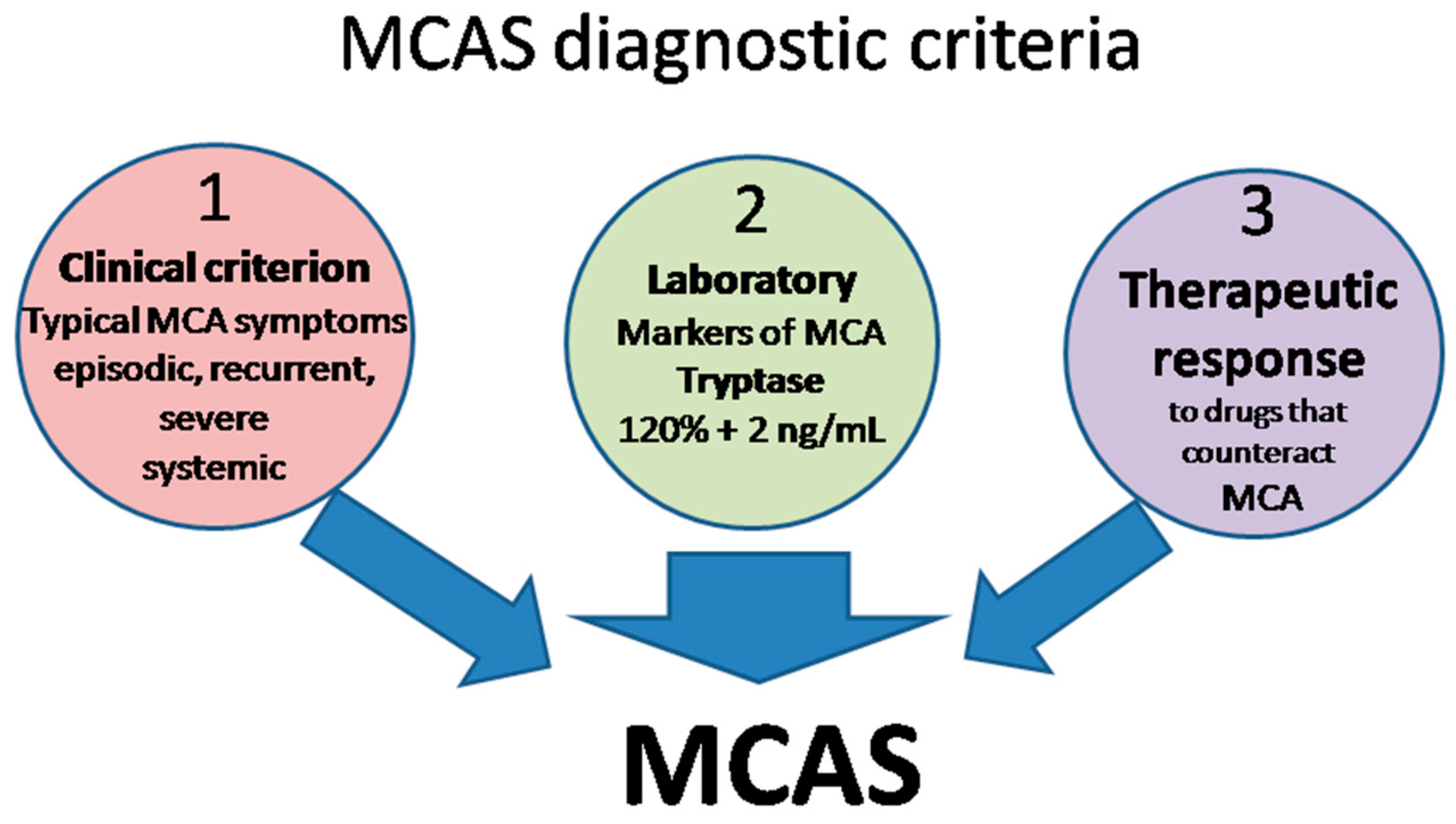

The definition of MCAS is based on three types of criteria (Figure 2) that all have to be met for an MCAS diagnosis to be established [10][15][17][18].

- Clinical: typical MC activation symptoms, which are episodic, recurrent, severe (often taking the form of anaphylaxis) and systemic (involving two organ systems at least);

- Laboratory: markers of MC activation—event-related serum tryptase level elevated above 120% of the individual’s serum baseline + 2 ng/mL;

- Therapeutic: clinical response to drugs that counteract MC mediators or prevent their release.

Figure 2. MCAS diagnostic criteria. MCA, mast cell activation; MCAS mast cell activation syndrome.

Symptoms of MCAS are multi-organ/system and extremely polymorphous, but only a small number of them are taken into consideration when establishing the diagnosis [19]. For example neuro-psychiatric manifestations were recently excluded, although many patients listed “brain fog” [20] as one of their main complaints, together with stress as an important trigger [21][22].

The most important classification criterion for MCAS is clonality (clonal vs. non-clonal). Clonal MC disturbances include the presence of c-KIT mutations (usually the D816V gain-of-function mutation, but not only) and/or expression of CD25, CD2 or CD30 on MCs [16]. If this is the case, MCAS is considered primary. In time, patients suffering from primary MCAS may develop overt SM. If MC activation is due to an allergic condition or another hypersensitivity disorder (IgE or non-IgE mediated, as for example drugs interacting with MRGPRX2) [23], then MCAS is classified as secondary (non-clonal). On the other hand, if there is no clonality, and no other specific cause can be identified, the MCAS is considered idiopathic. Combined forms of MCAS were also described, in which patients have traits of both primary and secondary MCAS (clonality + documented IgE-dependent allergy for example) and fall into the category of mixed MCAS [16].

MCAS differential diagnosis includes a large number of medical areas, conditions and disorders: infectious diseases (severe viral/bacterial/parasitic infections, septic shock, acute gastrointestinal infection), gastrointestinal (food intoxication, VIPoma, gastrinoma, irritable bowel syndrome, eosinophilic gastroenteritis or esophagitis, inflammatory bowel disease), cardiovascular (endocarditis or endomyocarditis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, aortic stenosis with syncope), endocrine (pheochromocytoma, carcinoid, medullary thyroid carcinoma), neuropsychiatric (anxiety/panic attacks, vasovagal syncope), cutaneous (different kinds of urticaria and angioedema, drug related pruritus/rashes, rosacea, vasculitis, atopic dermatitis). Furthermore, differential diagnosis should take into consideration two conditions where there is a chronic systemic elevation of MC mediators without MCs undue activation, namely histamine intolerance (HIT) and hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HαT). A complete physical examination, combined with a detailed patient history and laboratory assessment of specific markers, can help exclude these conditions [24].

4. Treatment

For most patients with MC-associated symptoms a cure is not possible at present. The management of these patients includes identification and avoidance of triggers, medications that block mediator effects on tissues and/or mediator release, and in severe cases, drugs that reduce the number of MCs. In addition, the symptomatic treatment of specific complaints is useful. Management should be multidisciplinary and individualized, considering the complexity of most cases and patients’ unique constellation of symptoms, reactions to different triggers and response to treatment.

The list of triggers that can activate MCs is extensive and includes many everyday life substances (e.g., alcohol, cigarettes, chemicals including drugs, and high histamine foods) or situations (e.g., emotional stress, cold, heat, UV light, travel by car). Avoiding triggers is not only difficult, but often the patient (and therefore the doctor) is unaware of which of the substances contained in a product may be responsible for the symptoms. To help clarify personal susceptibilities patients are advised to keep a journal, while family members should also be educated. Lifestyle changes include adopting a low-histamine diet, including exercise in the daily routine, balancing diet with supplemental prebiotics and/or probiotics, reducing stress and getting enough sleep.

Patients with anaphylaxis should receive education on presenting signs and symptoms, methods of avoiding known triggers, and should be referred to an allergist/immunologist [25].

The main pharmacological therapies include:

- An epinephrine autoinjector should be carried by all patients who had an anaphylaxis episode in their personal history—especially patients with known allergies to insect venoms—or who have a known risk of developing one. Epinephrine should be administered intramuscularly as soon as the first signs are noticed, or after insect bites and stings, in a dose of 0.01 mg/kg to a maximum of 0.5 mg in adults and 0.3 mg in children [25].

- Antihistamines are the first line of treatment for patients with non-life-threatening symptoms. They act by binding to, and blocking histamine receptors in the target tissues, thus reducing the impact of MC degranulation. Decades of clinical practice have established that the use of antihistamines alleviates symptoms such as itching, pain, urticaria, and acid reflux [26][27]. If symptom control cannot be achieved with the highest recommended doses of H2 antihistamines, a combination of non-sedating H1 and H2 antihistamines can be attempted, especially if the patient associates gastric symptoms [28]. Most patients have benefited from long-term antihistamine use, with good tolerance and minimum side effects [28].

- Leukotriene inhibitors are used in asthma and respiratory symptoms with probable underlying bronchoconstriction with allergic triggers that do not fulfil the criteria for asthma. They are also used in the treatment of allergic rhinitis, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Drugs with two mechanisms of action are currently approved: leukotriene receptor blockers (montelukast and zafirlukast) and 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors that block synthesis of leukotrienes from arachidonic acid (zileuton). Leukotriene inhibitors can be prescribed in combination with antihistamines [29][30][31].

- MC stabilizers increase the threshold for MC degranulation signaling. Cromolyn sodium and nedocromil are currently approved. Although very promising on paper, these drugs are not more effective than antihistamines and leukotriene inhibitors, with possibly more significant side effects. Consequently, they are not routinely prescribed. Moreover, ketotifen (a second-generation H1 receptor antagonist with higher brain permeability compared with the newer second-generation antagonists desloratadine and levocetirizine) has MC stabilizer activity. Desloratadine and cetirizine have also been reported as MC stabilizers, although doses significantly higher than the ones currently used for therapy were required [32][33][34][35][36].

- Steroids should only be used short term for acute exacerbations of symptoms not controlled by standard therapy. Potential uses include edema, urticaria, wheezing, diarrhea and severe pain [37].

- Biologics: omalizumab, an IgE receptor blocker, effectively controls MC-mediated symptoms, improves the patients’ quality of life, and should be recommended as low-dose long-term therapy to persons at risk of anaphylaxis [38][39]. Emerging kinase inhibitors (imatinib, mitostaurine, avapritinib) inhibit MC proliferation and IgE-dependent MC activation. These drugs may represent future effective therapies for patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis [26].

- DAO oral supplements should be considered in the case of HIT [40].

- Natural components with suggested MC stabilizing properties may be useful in the management of certain patients. Examples include quercetin, luteolin, resveratrol and green tea [41][42][43][44].

References

- Stassen, M.; Hultner, L.; Schmitt, E. Classical and Alternative Pathways of Mast Cell Activation. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 22, 115–140.

- Gurish, M.F.; Austen, K.F. Developmental Origin and Functional Specialization of Mast Cell Subsets. Immunity 2012, 37, 25–33.

- Friend, D.S.; Gurish, M.F.; Austen, K.F.; Hunt, J.; Stevens, R.L. Senescent Jejunal Mast Cells and Eosinophils in the Mouse Preferentially Translocate to the Spleen and Draining Lymph Node, Respectively, During the Recovery Phase of Helminth Infection. Immunol. 2000, 165, 344–352. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.344.

- Galli, S.J.; Grimbaldeston, M.; Tsai, M. Immunomodulatory Mast Cells: Negative, as Well as Positive, Regulators of Immunity. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 478–486.

- Gould, H.J.; Sutton, B.J. IgE in Allergy and Asthma Today. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 205–217.

- Abraham, S.N.; St. John, A.L. Mast Cell-Orchestrated Immunity to Pathogens. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 440–452.

- Wernersson, S.; Pejler, G. Mast Cell Secretory Granules: Armed for Battle. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 478–494.

- Irani, A.A.; Schechter, N.M.; Craig, S.S.; DeBlois, G.; Schwartz, L.B. Two Types of Human Mast Cells That Have Distinct Neutral Protease Compositions. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 4464–4468. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.83.12.4464.

- Douaiher, J.; Succar, J.; Lancerotto, L.; Gurish, M.F.; Orgill, D.P.; Hamilton, M.J.; Krilis, S.A.; Stevens, R.L. Development of Mast Cells and Importance of Their Tryptase and Chymase Serine Proteases in Inflammation and Wound Healing. In Advances in Immunology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 122, pp. 211–252.

- Akin, C.; Valent, P.; Metcalfe, D.D. Mast Cell Activation Syndrome: Proposed Diagnostic Criteria. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 1099–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.035.

- Theoharides, T.C.; Tsilioni, I.; Ren, H. Recent Advances in Our Understanding of Mast Cell Activation–or Should It Be Mast Cell Mediator Disorders? Expert Rev. Immunol. 2019, 15, 639–656.

- Molderings, G.J.; Haenisch, B.; Bogdanow, M.; Fimmers, R.; Nöthen, M.M. Familial Occurrence of Systemic Mast Cell Activation Disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76241. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076241.

- Weinstock, L.B.; Pace, L.A.; Rezaie, A.; Afrin, L.B.; Molderings, G.J. Mast Cell Activation Syndrome: A Primer for the Gastroenterologist. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 965–982.

- Jackson, C.W.; Pratt, C.M.; Rupprecht, C.P.; Pattanaik, D.; Krishnaswamy, G. Mastocytosis and Mast Cell Activation Disorders: Clearing the Air. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11270.

- Valent, P.; Akin, C.; Arock, M.; Brockow, K.; Butterfield, J.H.; Carter, M.C.; Castells, M.; Escribano, L.; Hartmann, K.; Lieberman, P.; et al. Definitions, Criteria and Global Classification of Mast Cell Disorders with Special Reference to Mast Cell Activation Syndromes: A Consensus Proposal. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2012, 157, 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1159/000328760.

- Valent, P.; Hartmann, K.; Bonadonna, P.; Gülen, T.; Brockow, K.; Alvarez-Twose, I.; Hermine, O.; Niedoszytko, M.; Carter, M.C.; Hoermann, G.; et al. Global Classification of Mast Cell Activation Disorders: An ICD-10-CM–Adjusted Proposal of the ECNM-AIM Consortium. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 1941–1950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2022.05.007.

- Valent, P. Mast Cell Activation Syndromes: Definition and Classification. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 68, 417–424.

- Valent, P.; Akin, C.; Bonadonna, P.; Hartmann, K.; Brockow, K.; Niedoszytko, M.; Nedoszytko, B.; Siebenhaar, F.; Sperr, W.R.; Oude Elberink, J.N.G.; et al. Proposed Diagnostic Algorithm for Patients with Suspected Mast Cell Activation Syndrome. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 1125–1133.e1.

- Gülen, T.; Akin, C.; Bonadonna, P.; Siebenhaar, F.; Broesby-Olsen, S.; Brockow, K.; Niedoszytko, M.; Nedoszytko, B.; Oude Elberink, H.N.G.; Butterfield, J.H.; et al. Selecting the Right Criteria and Proper Classification to Diagnose Mast Cell Activation Syndromes: A Critical Review. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 3918–3928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2021.06.011.

- Theoharides, T.C.; Stewart, J.M.; Hatziagelaki, E. Brain “Fog,” Inflammation a Nd Obesity: Key Aspects of Neuropsychiatric Disorders Improved by Luteolin. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00225.

- Jennings, S.; Russell, N.; Jennings, B.; Slee, V.; Sterling, L.; Castells, M.; Valent, P.; Akin, C. The Mastocytosis Society Survey on Mast Cell Disorders: Patient Experiences and Perceptions. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2014, 2, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2013.09.004.

- Afrin, L.B.; Pöhlau, D.; Raithel, M.; Haenisch, B.; Dumoulin, F.L.; Homann, J.; Mauer, U.M.; Harzer, S.; Molderings, G.J. Mast Cell Activation Disease: An Underappreciated Cause of Neurologic and Psychiatric Symptoms and Diseases. Behav. Immun. 2015, 50, 314–321.

- McNeil, B.D.; Pundir, P.; Meeker, S.; Han, L.; Undem, B.J.; Kulka, M.; Dong, X. Identification of a Mast-Cell-Specific Receptor Crucial for Pseudo-Allergic Drug Reactions. Nature 2015, 519, 237–241. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14022.

- Weiler, C.R. Mast Cell Activation Syndrome: Tools for Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 498–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.022.

- Shaker, M.S.; Wallace, D.V.; Golden, D.B.K.; Oppenheimer, J.; Bernstein, J.A.; Campbell, R.L.; Dinakar, C.; Ellis, A.; Greenhawt, M.; Khan, D.A.; et al. Anaphylaxis—A 2020 Practice Parameter Update, Systematic Review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Analysis. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1082–1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.017.

- Valent, P.; Hartmann, K.; Bonadonna, P.; Niedoszytko, M.; Triggiani, M.; Arock, M.; Brockow, K. Mast Cell Activation Syndromes: Collegium Internationale Allergologicum Update 2022. Int. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 183, 693–705.

- Thangam, E.B.; Jemima, E.A.; Singh, H.; Baig, M.S.; Khan, M.; Mathias, C.B.; Church, M.K.; Saluja, R. The Role of Histamine and Histamine Receptors in Mast Cell-Mediated Allergy and Inflammation: The Hunt for New Therapeutic Targets. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1873.

- Hamilton, M.J. Nonclonal Mast Cell Activation Syndrome: A Growing Body of Evidence. Allergy Clin. North Am. 2018, 38, 469–481.

- Virchow, J.C.; Bachert, C. Efficacy and Safety of Montelukast in Adults with Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis. Med. 2006, 100, 1952–1959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.02.026.

- Lu, P.; Schrag, M.L.; Slaughter, D.E.; Raab, C.E.; Shou, M.; Rodrigues, A.D. Mechanism-Based Inhibition of Human Liver Microsomal Cytochrome P450 1A2 by Zileuton, A 5-Lipoxygenase Inhibitor. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 1352–1360. https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.31.11.1352.

- Cardet, J.C.; Akin, C.; Lee, M.J. Mastocytosis: Update on Pharmacotherapy and Future Directions. Expert Opin. 2013, 14, 2033–2045.

- Weller, K.; Maurer, M. Desloratadine Inhibits Human Skin Mast Cell Activation and Histamine Release. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2723–2726.

- Fujimura, R.; Asada, A.; Aizawa, M.; Kazama, I. Cetirizine More Potently Exerts Mast Cell-Stabilizing Property than Diphenhydramine. Drug Discov. Ther. 2022, 16, 245–250. https://doi.org/10.5582/ddt.2022.01067.

- Sokol, K.C.; Amar, N.K.; Starkey, J.; Grant, J.A. Ketotifen in the Management of Chronic Urticaria: Resurrection of an Old Drug. Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2013, 111, 433–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2013.10.003.

- Unno, K.; Ozaki, T.; Mohammad, S.; Tsuno, S.; Ikeda-Sagara, M.; Honda, K.; Ikeda, M. First and Second Generation H1 Histamine Receptor Antagonists Produce Different Sleep-Inducing Profiles in Rats. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 683, 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.03.017.

- Okayama, Y.; Benyon, R.C.; Rees, P.H.; Lowman, M.A.; Hillier, K.; Church, M.K. Inhibition Profiles of Sodium Cromoglycate and Nedocromil Sodium on Mediator Release from Mast Cells of Human Skin, Lung, Tonsil, Adenoid and Intestine. Exp. Allergy 1992, 22, 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb03102.x.

- Castells, M.; Butterfield, J. Mast Cell Activation Syndrome and Mastocytosis: Initial Treatment Options and Long-Term Management. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 1097–1106.

- Berry, R.; Hollingsworth, P.; Lucas, M. Successful Treatment of Idiopathic Mast Cell Activation Syndrome with Low-Dose Omalizumab. Transl. Immunol. 2019, 8, e01075. https://doi.org/10.1002/cti2.1075.

- Lemal, R.; Fouquet, G.; Terriou, L.; Vaes, M.; Livideanu, C.B.; Frenzel, L.; Barete, S.; Canioni, D.; Lhermitte, L.; Rossignol, J.; et al. Omalizumab Therapy for Mast Cell-Mediator Symptoms in Patients with ISM, CM, MMAS, and MCAS. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 2387–2395.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.03.039.

- Kettner, L.; Seitl, I.; Fischer, L. Toward Oral Supplementation of Diamine Oxidase for the Treatment of Histamine Intolerance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132621.

- Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Skrovankova, S.; Sochor, J. Quercetin and Its Anti-Allergic Immune Response. Molecules 2016, 21, 623.

- Hao, Y.; Che, D.; Yu, Y.; Liu, L.; Mi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, J.; Li, W.; Ji, M.; Geng, S.; et al. Luteolin Inhibits FcεRΙ- and MRGPRX2-Mediated Mast Cell Activation by Regulating Calcium Signaling Pathways. Res. 2022, 36, 2197–2206. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7447.

- Shirley, D.; McHale, C.; Gomez, G. Resveratrol Preferentially Inhibits IgE-Dependent PGD2 Biosynthesis but Enhances TNF Production from Human Skin Mast Cells. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2016, 1860, 678–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.01.006.

- Maeda-Yamamoto, M. Human Clinical Studies of Tea Polyphenols in Allergy or Life Style-Related Diseases. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 6148–6155. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612811319340009.