| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yasuyuki Matsumoto | -- | 3690 | 2023-07-14 23:09:05 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 3690 | 2023-07-17 04:31:14 | | |

Video Upload Options

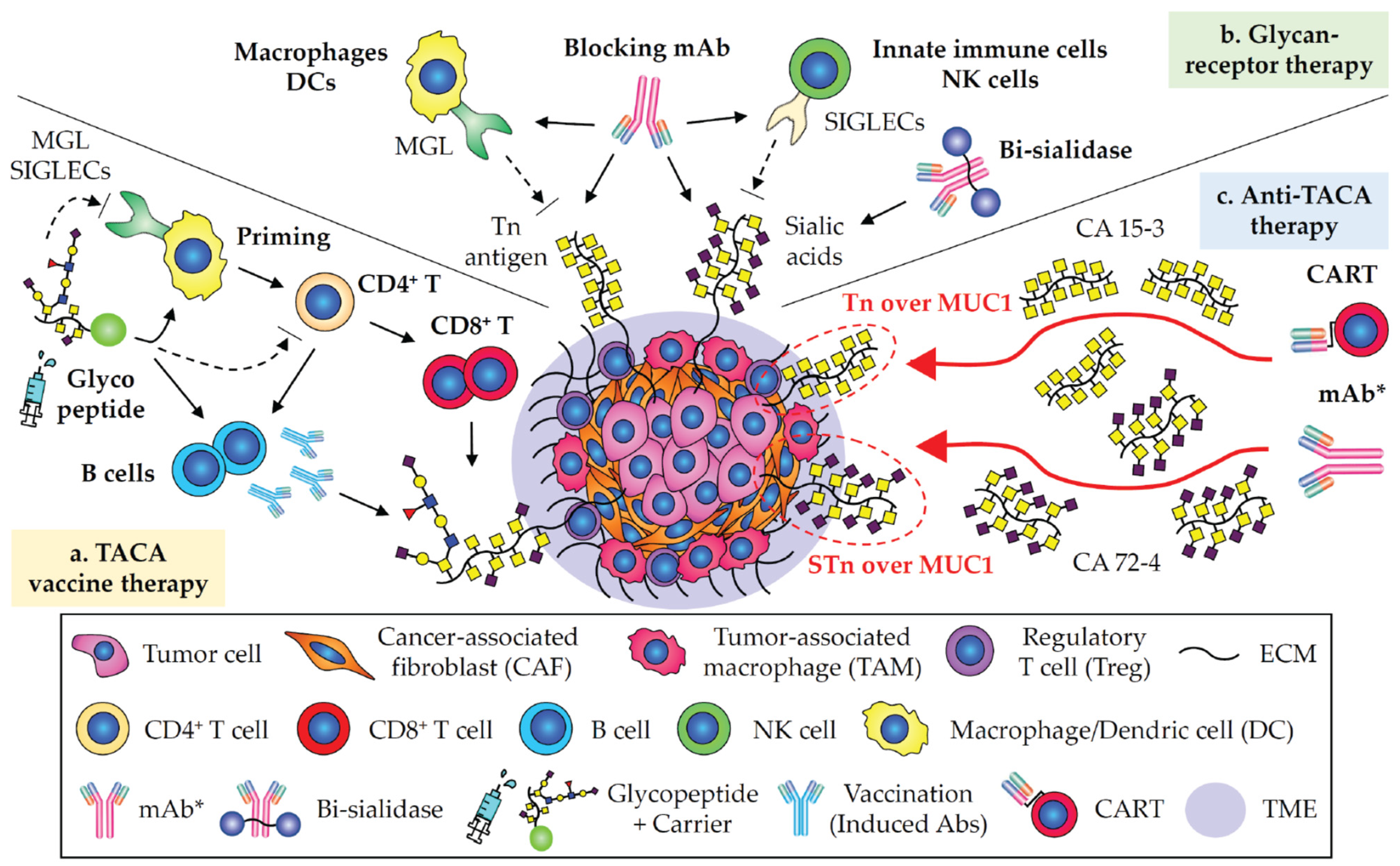

Glycosylation is one of the most pivotal post-translational modifications on all types of biomolecules for the formation of glycoproteins, glycolipids, and glycoRNAs in a tissue-type specific manner. Normal glycans participate in biological events such as development, metabolism, differentiation, and immunity in mammalian cells. In cancers, the altered glycosylation, known as tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens (TACAs), is specifically expressed on cell surface molecules and play important roles in facilitating tumor formation, progression, metastasis, and immunosurveillance evasion by generating the vulnerable tumor microenvironment through the interaction of glycan binding receptors expressed on immune cells. TACAs are potential tumor glyco-biomarkers, glycoimmune checkpoints, and therapeutics.

1. Tn and STn Antigens as Pan-Carcinoma TACAs

2. CA 19-9 in Pancreatic and Digestive Carcinomas

3. GD2 in Neuroblastoma and Glioma

4. Targeting Neoantigens in Carcinomas

5. Immunotherapies Involving in Glycobiology and Glycoimmunology

References

- Kudelka, M.R.; Ju, T.; Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Cummings, R.D. Simple sugars to complex disease--mucin-type O-glycans in cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2015, 126, 53–135.

- Stowell, S.R.; Ju, T.; Cummings, R.D. Protein glycosylation in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2015, 10, 473–510.

- Itzkowitz, S.H.; Bloom, E.J.; Lau, T.S.; Kim, Y.S. Mucin associated Tn and sialosyl-Tn antigen expression in colorectal polyps. Gut 1992, 33, 518–523.

- Bennett, E.P.; Mandel, U.; Clausen, H.; Gerken, T.A.; Fritz, T.A.; Tabak, L.A. Control of mucin-type O-glycosylation: A classification of the polypeptide GalNAc-transferase gene family. Glycobiology 2012, 22, 736–756.

- Ju, T.; Wang, Y.; Aryal, R.P.; Lehoux, S.D.; Ding, X.; Kudelka, M.R.; Cutler, C.; Zeng, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, X.; et al. Tn and sialyl-Tn antigens, aberrant O-glycomics as human disease markers. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2013, 7, 618–631.

- Ju, T.; Aryal, R.P.; Kudelka, M.R.; Wang, Y.; Cummings, R.D. The Cosmc connection to the Tn antigen in cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2014, 14, 63–81.

- Chia, J.; Goh, G.; Bard, F. Short O-GalNAc glycans: Regulation and role in tumor development and clinical perspectives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 1623–1639.

- Cervoni, G.E.; Cheng, J.J.; Stackhouse, K.A.; Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Cummings, R.D. O-glycan recognition and function in mice and human cancers. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 1541–1564.

- Gupta, R.; Leon, F.; Rauth, S.; Batra, S.K.; Ponnusamy, M.P. A Systematic Review on the Implications of O-linked Glycan Branching and Truncating Enzymes on Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cells 2020, 9, 446.

- Wandall, H.H.; Nielsen, M.A.I.; King-Smith, S.; de Haan, N.; Bagdonaite, I. Global functions of O-glycosylation: Promises and challenges in O-glycobiology. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 7183–7212.

- Hitchcock, C.L.; Povoski, S.P.; Mojzisik, C.M.; Martin, E.W., Jr. Survival Advantage Following TAG-72 Antigen-Directed Cancer Surgery in Patients With Colorectal Carcinoma: Proposed Mechanisms of Action. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 731350.

- Inoue, M.; Fujita, M.; Nakazawa, A.; Ogawa, H.; Tanizawa, O. Sialyl-Tn, sialyl-Lewis Xi, CA 19-9, CA 125, carcinoembryonic antigen, and tissue polypeptide antigen in differentiating ovarian cancer from benign tumors. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 79, 434–440.

- Kobayashi, H.; Terao, T.; Kawashima, Y. Serum sialyl Tn as an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1992, 10, 95–101.

- Ryuko, K.; Iwanari, O.; Nakayama, S.; Iida, K.; Kitao, M. Clinical evaluation of serum sialosyl-Tn antigen levels in comparison with CA 125 levels in gynecologic cancers. Cancer 1992, 69, 2368–2378.

- Gidwani, K.; Nadeem, N.; Huhtinen, K.; Kekki, H.; Heinosalo, T.; Hynninen, J.; Perheentupa, A.; Poutanen, M.; Carpen, O.; Pettersson, K.; et al. Europium Nanoparticle-Based Sialyl-Tn Monoclonal Antibody Discriminates Epithelial Ovarian Cancer-Associated CA125 from Benign Sources. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2019, 4, 299–310.

- Salminen, L.; Nadeem, N.; Jain, S.; Grenman, S.; Carpen, O.; Hietanen, S.; Oksa, S.; Lamminmaki, U.; Pettersson, K.; Gidwani, K.; et al. A longitudinal analysis of CA125 glycoforms in the monitoring and follow up of high grade serous ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 156, 689–694.

- Wang, Y.S.; Ren, S.F.; Jiang, W.; Lu, J.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, X.P.; Cao, R.; Xu, C.J. CA125-Tn ELISA assay improves specificity of pre-operative diagnosis of ovarian cancer among patients with elevated serum CA125 levels. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 788.

- Jin, X.; Du, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X. Evaluation of serum CA125-Tn glycoform in peritoneal dissemination and surgical completeness of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 134.

- Motoo, Y.; Kawakami, H.; Watanabe, H.; Satomura, Y.; Ohta, H.; Okai, T.; Makino, H.; Toya, D.; Sawabu, N. Serum sialyl-Tn antigen levels in patients with digestive cancers. Oncology 1991, 48, 321–326.

- Takahashi, I.; Maehara, Y.; Kusumoto, T.; Kohnoe, S.; Kakeji, Y.; Baba, H.; Sugimachi, K. Combined evaluation of preoperative serum sialyl-Tn antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen levels is prognostic for gastric cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 1994, 69, 163–166.

- Nakata, B.; Hirakawa, Y.S.C.K.; Kato, Y.; Yamashita, Y.; Maeda, K.; Onoda, N.; Sawada, T.; Sowa, M. Serum CA 125 level as a predictor of peritoneal dissemination in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer 1998, 83, 2488–2492.

- Tanaka-Okamoto, M.; Hanzawa, K.; Mukai, M.; Takahashi, H.; Ohue, M.; Miyamoto, Y. Correlation of serum sialyl Tn antigen values determined by immunoassay and SRM based method. Anal. Biochem. 2018, 544, 42–48.

- Hashiguchi, Y.; Kasai, M.; Fukuda, T.; Ichimura, T.; Yasui, T.; Sumi, T. Serum Sialyl-Tn (STN) as a Tumor Marker in Patients with Endometrial Cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2016, 22, 501–504.

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, N. Clinical evaluation of CEA, CA19-9, CA72-4 and CA125 in gastric cancer patients with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 12, 397.

- Chen, Z.Q.; Huang, L.S.; Zhu, B. Assessment of Seven Clinical Tumor Markers in Diagnosis of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Dis. Markers 2018, 2018, 9845123.

- Cummings, R.D. The repertoire of glycan determinants in the human glycome. Mol. Biosyst. 2009, 5, 1087–1104.

- Singh, S.K.; Streng-Ouwehand, I.; Litjens, M.; Kalay, H.; Saeland, E.; van Kooyk, Y. Tumour-associated glycan modifications of antigen enhance MGL2 dependent uptake and MHC class I restricted CD8 T cell responses. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 1371–1383.

- Julien, S.; Videira, P.A.; Delannoy, P. Sialyl-tn in cancer: (How) did we miss the target? Biomolecules 2012, 2, 435–466.

- Hakomori, S.; Wang, S.M.; Young, W.W., Jr. Isoantigenic expression of Forssman glycolipid in human gastric and colonic mucosa: Its possible identity with “A-like antigen” in human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 3023–3027.

- Taniguchi, N.; Yokosawa, N.; Narita, M.; Mitsuyama, T.; Makita, A. Expression of Forssman antigen synthesis and degradation in human lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1981, 67, 577–583.

- Lehoux, S.; Mi, R.; Aryal, R.P.; Wang, Y.; Schjoldager, K.T.; Clausen, H.; van Die, I.; Han, Y.; Chapman, A.B.; Cummings, R.D.; et al. Identification of distinct glycoforms of IgA1 in plasma from patients with immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy and healthy individuals. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2014, 13, 3097–3113.

- Suzuki, H.; Novak, J. IgA glycosylation and immune complex formation in IgAN. Semin. Immunopathol. 2021, 43, 669–678.

- Matsumoto, Y.; Aryal, R.P.; Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Park, S.S.; Wever, W.J.; Lehoux, S.; Stavenhagen, K.; van Wijk, J.A.E.; Van Die, I.; Chapman, A.B.; et al. Identification and characterization of circulating immune complexes in IgA nephropathy. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm8783.

- Hirohashi, S.; Clausen, H.; Yamada, T.; Shimosato, Y.; Hakomori, S. Blood group A cross-reacting epitope defined by monoclonal antibodies NCC-LU-35 and -81 expressed in cancer of blood group O or B individuals: Its identification as Tn antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 7039–7043.

- Springer, G.F.; Chandrasekaran, E.V.; Desai, P.R.; Tegtmeyer, H. Blood group Tn-active macromolecules from human carcinomas and erythrocytes: Characterization of and specific reactivity with mono- and poly-clonal anti-Tn antibodies induced by various immunogens. Carbohydr. Res. 1988, 178, 271–292.

- Takahashi, H.K.; Metoki, R.; Hakomori, S. Immunoglobulin G3 monoclonal antibody directed to Tn antigen (tumor-associated alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminyl epitope) that does not cross-react with blood group A antigen. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 4361–4367.

- Ward, P.L.; Koeppen, H.; Hurteau, T.; Schreiber, H. Tumor antigens defined by cloned immunological probes are highly polymorphic and are not detected on autologous normal cells. J. Exp. Med. 1989, 170, 217–232.

- Bigbee, W.L.; Langlois, R.G.; Stanker, L.H.; Vanderlaan, M.; Jensen, R.H. Flow cytometric analysis of erythrocyte populations in Tn syndrome blood using monoclonal antibodies to glycophorin A and the Tn antigen. Cytometry 1990, 11, 261–271.

- Numata, Y.; Nakada, H.; Fukui, S.; Kitagawa, H.; Ozaki, K.; Inoue, M.; Kawasaki, T.; Funakoshi, I.; Yamashina, I. A monoclonal antibody directed to Tn antigen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 170, 981–985.

- Pancino, G.F.; Osinaga, E.; Vorauher, W.; Kakouche, A.; Mistro, D.; Charpin, C.; Roseto, A. Production of a monoclonal antibody as immunohistochemical marker on paraffin embedded tissues using a new immunization method. Hybridoma 1990, 9, 389–395.

- King, M.J.; Parsons, S.F.; Wu, A.M.; Jones, N. Immunochemical studies on the differential binding properties of two monoclonal antibodies reacting with Tn red cells. Transfusion 1991, 31, 142–149.

- Thurnher, M.; Clausen, H.; Sharon, N.; Berger, E.G. Use of O-glycosylation-defective human lymphoid cell lines and flow cytometry to delineate the specificity of Moluccella laevis lectin and monoclonal antibody 5F4 for the Tn antigen (GalNAc alpha 1-O-Ser/Thr). Immunol. Lett. 1993, 36, 239–243.

- Avichezer, D.; Springer, G.F.; Schechter, B.; Arnon, R. Immunoreactivities of polyclonal and monoclonal anti-T and anti-Tn antibodies with human carcinoma cells, grown in vitro and in a xenograft model. Int. J. Cancer 1997, 72, 119–127.

- Reis, C.A.; Sorensen, T.; Mandel, U.; David, L.; Mirgorodskaya, E.; Roepstorff, P.; Kihlberg, J.; Hansen, J.E.; Clausen, H. Development and characterization of an antibody directed to an alpha-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine glycosylated MUC2 peptide. Glycoconj. J. 1998, 15, 51–62.

- Sorensen, A.L.; Reis, C.A.; Tarp, M.A.; Mandel, U.; Ramachandran, K.; Sankaranarayanan, V.; Schwientek, T.; Graham, R.; Taylor-Papadimitriou, J.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; et al. Chemoenzymatically synthesized multimeric Tn/STn MUC1 glycopeptides elicit cancer-specific anti-MUC1 antibody responses and override tolerance. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 96–107.

- Ando, H.; Matsushita, T.; Wakitani, M.; Sato, T.; Kodama-Nishida, S.; Shibata, K.; Shitara, K.; Ohta, S. Mouse-human chimeric anti-Tn IgG1 induced anti-tumor activity against Jurkat cells in vitro and in vivo. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 1739–1744.

- Danussi, C.; Coslovi, A.; Campa, C.; Mucignat, M.T.; Spessotto, P.; Uggeri, F.; Paoletti, S.; Colombatti, A. A newly generated functional antibody identifies Tn antigen as a novel determinant in the cancer cell-lymphatic endothelium interaction. Glycobiology 2009, 19, 1056–1067.

- Kubota, T.; Matsushita, T.; Niwa, R.; Kumagai, I.; Nakamura, K. Novel anti-Tn single-chain Fv-Fc fusion proteins derived from immunized phage library and antibody Fc domain. Anticancer Res. 2010, 30, 3397–3405.

- Brooks, C.L.; Schietinger, A.; Borisova, S.N.; Kufer, P.; Okon, M.; Hirama, T.; Mackenzie, C.R.; Wang, L.X.; Schreiber, H.; Evans, S.V. Antibody recognition of a unique tumor-specific glycopeptide antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10056–10061.

- Welinder, C.; Baldetorp, B.; Borrebaeck, C.; Fredlund, B.M.; Jansson, B. A new murine IgG1 anti-Tn monoclonal antibody with in vivo anti-tumor activity. Glycobiology 2011, 21, 1097–1107.

- Blixt, O.; Lavrova, O.I.; Mazurov, D.V.; Clo, E.; Kracun, S.K.; Bovin, N.V.; Filatov, A.V. Analysis of Tn antigenicity with a panel of new IgM and IgG1 monoclonal antibodies raised against leukemic cells. Glycobiology 2012, 22, 529–542.

- Mazal, D.; Lo-Man, R.; Bay, S.; Pritsch, O.; Deriaud, E.; Ganneau, C.; Medeiros, A.; Ubillos, L.; Obal, G.; Berois, N.; et al. Monoclonal antibodies toward different Tn-amino acid backbones display distinct recognition patterns on human cancer cells. Implications for effective immuno-targeting of cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2013, 62, 1107–1122.

- Persson, N.; Stuhr-Hansen, N.; Risinger, C.; Mereiter, S.; Polonia, A.; Polom, K.; Kovacs, A.; Roviello, F.; Reis, C.A.; Welinder, C.; et al. Epitope mapping of a new anti-Tn antibody detecting gastric cancer cells. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 635–645.

- Naito, S.; Takahashi, T.; Onoda, J.; Uemura, S.; Ohyabu, N.; Takemoto, H.; Yamane, S.; Fujii, I.; Nishimura, S.I.; Numata, Y. Generation of Novel Anti-MUC1 Monoclonal Antibodies with Designed Carbohydrate Specificities Using MUC1 Glycopeptide Library. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 7493–7505.

- Matsumoto, Y.; Kudelka, M.R.; Hanes, M.S.; Lehoux, S.; Dutta, S.; Jones, M.B.; Stackhouse, K.A.; Cervoni, G.E.; Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Smith, D.F.; et al. Identification of Tn antigen O-GalNAc-expressing glycoproteins in human carcinomas using novel anti-Tn recombinant antibodies. Glycobiology 2020, 30, 282–300.

- Colcher, D.; Hand, P.H.; Nuti, M.; Schlom, J. A spectrum of monoclonal antibodies reactive with human mammary tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 3199–3203.

- Johnson, V.G.; Schlom, J.; Paterson, A.J.; Bennett, J.; Magnani, J.L.; Colcher, D. Analysis of a human tumor-associated glycoprotein (TAG-72) identified by monoclonal antibody B72.3. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 850–857.

- Kjeldsen, T.; Clausen, H.; Hirohashi, S.; Ogawa, T.; Iijima, H.; Hakomori, S. Preparation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies directed to the tumor-associated O-linked sialosyl-2—6 alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminyl (sialosyl-Tn) epitope. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 2214–2220.

- Muraro, R.; Kuroki, M.; Wunderlich, D.; Poole, D.J.; Colcher, D.; Thor, A.; Greiner, J.W.; Simpson, J.F.; Molinolo, A.; Noguchi, P.; et al. Generation and characterization of B72.3 second generation monoclonal antibodies reactive with the tumor-associated glycoprotein 72 antigen. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 4588–4596.

- An, Y.; Han, W.; Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Lu, D.; Feng, J.; Yang, D.; Song, L.; Yan, X. A novel anti-sTn monoclonal antibody 3P9 Inhibits human xenografted colorectal carcinomas. J. Immunother. 2013, 36, 20–28.

- Prendergast, J.M.; Galvao da Silva, A.P.; Eavarone, D.A.; Ghaderi, D.; Zhang, M.; Brady, D.; Wicks, J.; DeSander, J.; Behrens, J.; Rueda, B.R. Novel anti-Sialyl-Tn monoclonal antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates demonstrate tumor specificity and anti-tumor activity. mAbs 2017, 9, 615–627.

- Loureiro, L.R.; Sousa, D.P.; Ferreira, D.; Chai, W.; Lima, L.; Pereira, C.; Lopes, C.B.; Correia, V.G.; Silva, L.M.; Li, C.; et al. Novel monoclonal antibody L2A5 specifically targeting sialyl-Tn and short glycans terminated by alpha-2-6 sialic acids. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12196.

- Trabbic, K.R.; Kleski, K.A.; Shi, M.; Bourgault, J.P.; Prendergast, J.M.; Dransfield, D.T.; Andreana, P.R. Production of a mouse monoclonal IgM antibody that targets the carbohydrate Thomsen-nouveau cancer antigen resulting in in vivo and in vitro tumor killing. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 1437–1447.

- Kashmiri, S.V.; Shu, L.; Padlan, E.A.; Milenic, D.E.; Schlom, J.; Hand, P.H. Generation, characterization, and in vivo studies of humanized anticarcinoma antibody CC49. Hybridoma 1995, 14, 461–473.

- Hubert, P.; Heitzmann, A.; Viel, S.; Nicolas, A.; Sastre-Garau, X.; Oppezzo, P.; Pritsch, O.; Osinaga, E.; Amigorena, S. Antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity synapses form in mice during tumor-specific antibody immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 5134–5143.

- Lavrsen, K.; Madsen, C.B.; Rasch, M.G.; Woetmann, A.; Odum, N.; Mandel, U.; Clausen, H.; Pedersen, A.E.; Wandall, H.H. Aberrantly glycosylated MUC1 is expressed on the surface of breast cancer cells and a target for antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Glycoconj. J. 2013, 30, 227–236.

- Gong, Y.; Klein Wolterink, R.G.J.; Gulaia, V.; Cloosen, S.; Ehlers, F.A.I.; Wieten, L.; Graus, Y.F.; Bos, G.M.J.; Germeraad, W.T.V. Defucosylation of Tumor-Specific Humanized Anti-MUC1 Monoclonal Antibody Enhances NK Cell-Mediated Anti-Tumor Cell Cytotoxicity. Cancers 2021, 13, 2579.

- Matsumoto, Y.; Jia, N.; Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Cummings, R.D. Targeting Tn-positive tumors with an afucosylated recombinant anti-Tn IgG. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5027.

- Smorodin, E.; Sergeyev, B.; Klaamas, K.; Chuzmarov, V.; Kurtenkov, O. The relation of the level of serum anti-TF, -Tn and -alpha-Gal IgG to survival in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 10, 1674–1682.

- Lamarre, M.; Tremblay, T.; Bansept, M.A.; Robitaille, K.; Fradet, V.; Giguere, D.; Boudreau, D. A glycan-based plasmonic sensor for prostate cancer diagnosis. Analyst 2021, 146, 6852–6860.

- Smorodin, E.P.; Sergeyev, B.L. The level of IgG antibodies reactive to TF, Tn and alpha-Gal polyacrylamide-glycoconjugates in breast cancer patients: Relation to survival. Exp. Oncol. 2016, 38, 117–121.

- Springer, G.F.; Tegtmeyer, H. Origin of anti-Thomsen-Friedenreich (T) and Tn agglutinins in man and in White Leghorn chicks. Br. J. Haematol. 1981, 47, 453–460.

- Kjeldsen, T.; Hakomori, S.; Springer, G.F.; Desai, P.; Harris, T.; Clausen, H. Coexpression of sialosyl-Tn (NeuAc alpha 2—6GalNAc alpha 1—O-Ser/Thr) and Tn (GalNAc alpha 1—O-Ser/Thr) blood group antigens on Tn erythrocytes. Vox Sang. 1989, 57, 81–87.

- Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Priest, J.W.; Live, D.; Boons, G.J.; Song, X.; Cummings, R.D.; Mead, J.R. Microarray analysis of the human antibody response to synthetic Cryptosporidium glycopeptides. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013, 43, 901–907.

- DeCicco RePass, M.A.; Bhat, N.; Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Bunnell, S.; Cummings, R.D.; Ward, H.D. Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of UDP N-acetyl-alpha-d-galactosamine: Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 4 from Cryptosporidium parvum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2018, 221, 56–65.

- Dobrochaeva, K.; Khasbiullina, N.; Shilova, N.; Antipova, N.; Obukhova, P.; Ovchinnikova, T.; Galanina, O.; Blixt, O.; Kunz, H.; Filatov, A.; et al. Specificity of human natural antibodies referred to as anti-Tn. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 120, 74–82.

- Nardy, A.F.; Freire-de-Lima, L.; Freire-de-Lima, C.G.; Morrot, A. The Sweet Side of Immune Evasion: Role of Glycans in the Mechanisms of Cancer Progression. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 54.

- Saeland, E.; van Vliet, S.J.; Backstrom, M.; van den Berg, V.C.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.; Meijer, G.A.; van Kooyk, Y. The C-type lectin MGL expressed by dendritic cells detects glycan changes on MUC1 in colon carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2007, 56, 1225–1236.

- van Vliet, S.J.; van Liempt, E.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.; van Kooyk, Y. Differential regulation of C-type lectin expression on tolerogenic dendritic cell subsets. Immunobiology 2006, 211, 577–585.

- van Vliet, S.J.; Gringhuis, S.I.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.; van Kooyk, Y. Regulation of effector T cells by antigen-presenting cells via interaction of the C-type lectin MGL with CD45. Nat. Immunol. 2006, 7, 1200–1208.

- Dusoswa, S.A.; Verhoeff, J.; Abels, E.; Mendez-Huergo, S.P.; Croci, D.O.; Kuijper, L.H.; de Miguel, E.; Wouters, V.; Best, M.G.; Rodriguez, E.; et al. Glioblastomas exploit truncated O-linked glycans for local and distant immune modulation via the macrophage galactose-type lectin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 3693–3703.

- Cornelissen, L.A.M.; Blanas, A.; Zaal, A.; van der Horst, J.C.; Kruijssen, L.J.W.; O’Toole, T.; van Kooyk, Y.; van Vliet, S.J. Tn Antigen Expression Contributes to an Immune Suppressive Microenvironment and Drives Tumor Growth in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1622.

- da Costa, V.; van Vliet, S.J.; Carasi, P.; Frigerio, S.; Garcia, P.A.; Croci, D.O.; Festari, M.F.; Costa, M.; Landeira, M.; Rodriguez-Zraquia, S.A.; et al. The Tn antigen promotes lung tumor growth by fostering immunosuppression and angiogenesis via interaction with Macrophage Galactose-type lectin 2 (MGL2). Cancer Lett. 2021, 518, 72–81.

- Zizzari, I.G.; Napoletano, C.; Battisti, F.; Rahimi, H.; Caponnetto, S.; Pierelli, L.; Nuti, M.; Rughetti, A. MGL Receptor and Immunity: When the Ligand Can Make the Difference. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 450695.

- Cagnoni, A.J.; Perez Saez, J.M.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Marino, K.V. Turning-Off Signaling by Siglecs, Selectins, and Galectins: Chemical Inhibition of Glycan-Dependent Interactions in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 109.

- Peixoto, A.; Miranda, A.; Santos, L.L.; Ferreira, J.A. A roadmap for translational cancer glycoimmunology at single cell resolution. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 143.

- Derosiers, N.; Aguilar, W.; De Garamo, D.A.; Posey, A.D., Jr. Sweet Immune Checkpoint Targets to Enhance T Cell Therapy. J. Immunol. 2022, 208, 278–285.

- Ohta, M.; Ishida, A.; Toda, M.; Akita, K.; Inoue, M.; Yamashita, K.; Watanabe, M.; Murata, T.; Usui, T.; Nakada, H. Immunomodulation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells through ligation of tumor-produced mucins to Siglec-9. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 402, 663–669.

- Bhatia, R.; Gautam, S.K.; Cannon, A.; Thompson, C.; Hall, B.R.; Aithal, A.; Banerjee, K.; Jain, M.; Solheim, J.C.; Kumar, S.; et al. Cancer-associated mucins: Role in immune modulation and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019, 38, 223–236.

- Beatson, R.; Tajadura-Ortega, V.; Achkova, D.; Picco, G.; Tsourouktsoglou, T.D.; Klausing, S.; Hillier, M.; Maher, J.; Noll, T.; Crocker, P.R.; et al. The mucin MUC1 modulates the tumor immunological microenvironment through engagement of the lectin Siglec-9. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 1273–1281.

- Carrascal, M.A.; Severino, P.F.; Guadalupe Cabral, M.; Silva, M.; Ferreira, J.A.; Calais, F.; Quinto, H.; Pen, C.; Ligeiro, D.; Santos, L.L.; et al. Sialyl Tn-expressing bladder cancer cells induce a tolerogenic phenotype in innate and adaptive immune cells. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 8, 753–765.

- Thomas, D.; Sagar, S.; Caffrey, T.; Grandgenett, P.M.; Radhakrishnan, P. Truncated O-glycans promote epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stemness properties of pancreatic cancer cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 6885–6896.

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Dong, X.; Hu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, L.; Du, T.; Yang, L.; Wen, T.; An, G.; et al. Tn antigen promotes human colorectal cancer metastasis via H-Ras mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition activation. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2083–2092.

- Ju, T.; Lanneau, G.S.; Gautam, T.; Wang, Y.; Xia, B.; Stowell, S.R.; Willard, M.T.; Wang, W.; Xia, J.Y.; Zuna, R.E.; et al. Human tumor antigens Tn and sialyl Tn arise from mutations in Cosmc. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1636–1646.

- Sun, X.; Ju, T.; Cummings, R.D. Differential expression of Cosmc, T-synthase and mucins in Tn-positive colorectal cancers. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 827.

- Wang, Y.; Ju, T.; Ding, X.; Xia, B.; Wang, W.; Xia, L.; He, M.; Cummings, R.D. Cosmc is an essential chaperone for correct protein O-glycosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9228–9233.

- Wang, Y.; Jobe, S.M.; Ding, X.; Choo, H.; Archer, D.R.; Mi, R.; Ju, T.; Cummings, R.D. Platelet biogenesis and functions require correct protein O-glycosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16143–16148.

- Zeng, J.; Eljalby, M.; Aryal, R.P.; Lehoux, S.; Stavenhagen, K.; Kudelka, M.R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Ju, T.; von Andrian, U.H.; et al. Cosmc controls B cell homing. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3990.

- Zeng, J.; Aryal, R.P.; Stavenhagen, K.; Luo, C.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Cosmc deficiency causes spontaneous autoimmunity by breaking B cell tolerance. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg9118.

- Kudelka, M.R.; Hinrichs, B.H.; Darby, T.; Moreno, C.S.; Nishio, H.; Cutler, C.E.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Zeng, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Cosmc is an X-linked inflammatory bowel disease risk gene that spatially regulates gut microbiota and contributes to sex-specific risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 14787–14792.

- Stotter, B.R.; Talbot, B.E.; Capen, D.E.; Artelt, N.; Zeng, J.; Matsumoto, Y.; Endlich, N.; Cummings, R.D.; Schlondorff, J.S. Cosmc-dependent mucin-type O-linked glycosylation is essential for podocyte function. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2020, 318, F518–F530.

- Fu, J.; Gerhardt, H.; McDaniel, J.M.; Xia, B.; Liu, X.; Ivanciu, L.; Ny, A.; Hermans, K.; Silasi-Mansat, R.; McGee, S.; et al. Endothelial cell O-glycan deficiency causes blood/lymphatic misconnections and consequent fatty liver disease in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008, 118, 3725–3737.

- Borgert, A.; Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Song, X.; Lasanajak, Y.; Ju, T.; Liu, M.; Thompson, P.; Ragupathi, G.; Barany, G.; Smith, D.F.; et al. Deciphering structural elements of mucin glycoprotein recognition. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 1031–1039.

- Kudelka, M.R.; Gu, W.; Matsumoto, Y.; Ju, T.; Barnes, R.H.; Kardish, R.J.; Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Lehoux, S.; Zeng, J.; Cohen, C.; et al. Targeting Altered Glycosylation in Secreted Tumor Glycoproteins for Broad Cancer Detection. Glycobiology 2023, cwad035.

- Shields, R.L.; Lai, J.; Keck, R.; O’Connell, L.Y.; Hong, K.; Meng, Y.G.; Weikert, S.H.; Presta, L.G. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 26733–26740.

- Nose, M.; Wigzell, H. Biological significance of carbohydrate chains on monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 6632–6636.

- Subedi, G.P.; Barb, A.W. The Structural Role of Antibody N-Glycosylation in Receptor Interactions. Structure 2015, 23, 1573–1583.

- Ragupathi, G.; Liu, N.X.; Musselli, C.; Powell, S.; Lloyd, K.; Livingston, P.O. Antibodies against tumor cell glycolipids and proteins, but not mucins, mediate complement-dependent cytotoxicity. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 5706–5712.

- Pirro, M.; Rombouts, Y.; Stella, A.; Neyrolles, O.; Burlet-Schiltz, O.; van Vliet, S.J.; de Ru, A.H.; Mohammed, Y.; Wuhrer, M.; van Veelen, P.A.; et al. Characterization of Macrophage Galactose-type Lectin (MGL) ligands in colorectal cancer cell lines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2020, 1864, 129513.

- Veillon, L.; Fakih, C.; Abou-El-Hassan, H.; Kobeissy, F.; Mechref, Y. Glycosylation Changes in Brain Cancer. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 51–72.

- Salleh, S.; Thyagarajan, A.; Sahu, R.P. Exploiting the relevance of CA 19-9 in pancreatic cancer. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2020, 6, 31.

- Koprowski, H.; Steplewski, Z.; Mitchell, K.; Herlyn, M.; Herlyn, D.; Fuhrer, P. Colorectal carcinoma antigens detected by hybridoma antibodies. Somatic. Cell Genet. 1979, 5, 957–971.

- Magnani, J.L.; Nilsson, B.; Brockhaus, M.; Zopf, D.; Steplewski, Z.; Koprowski, H.; Ginsburg, V. A monoclonal antibody-defined antigen associated with gastrointestinal cancer is a ganglioside containing sialylated lacto-N-fucopentaose II. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 14365–14369.

- Magnani, J.L.; Steplewski, Z.; Koprowski, H.; Ginsburg, V. Identification of the gastrointestinal and pancreatic cancer-associated antigen detected by monoclonal antibody 19-9 in the sera of patients as a mucin. Cancer Res. 1983, 43, 5489–5492.

- Trinchera, M.; Aronica, A.; Dall’Olio, F. Selectin Ligands Sialyl-Lewis a and Sialyl-Lewis x in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Biology 2017, 6, 16.

- Yue, T.; Partyka, K.; Maupin, K.A.; Hurley, M.; Andrews, P.; Kaul, K.; Moser, A.J.; Zeh, H.; Brand, R.E.; Haab, B.B. Identification of blood-protein carriers of the CA 19-9 antigen and characterization of prevalence in pancreatic diseases. Proteomics 2011, 11, 3665–3674.

- Fuster, M.M.; Esko, J.D. The sweet and sour of cancer: Glycans as novel therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 526–542.

- Engle, D.D.; Tiriac, H.; Rivera, K.D.; Pommier, A.; Whalen, S.; Oni, T.E.; Alagesan, B.; Lee, E.J.; Yao, M.A.; Lucito, M.S.; et al. The glycan CA19-9 promotes pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in mice. Science 2019, 364, 1156–1162.

- Kannagi, R.; Izawa, M.; Koike, T.; Miyazaki, K.; Kimura, N. Carbohydrate-mediated cell adhesion in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2004, 95, 377–384.

- Biancone, L.; Araki, M.; Araki, K.; Vassalli, P.; Stamenkovic, I. Redirection of tumor metastasis by expression of E-selectin in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 1996, 183, 581–587.

- Takada, A.; Ohmori, K.; Takahashi, N.; Tsuyuoka, K.; Yago, A.; Zenita, K.; Hasegawa, A.; Kannagi, R. Adhesion of human cancer cells to vascular endothelium mediated by a carbohydrate antigen, sialyl Lewis A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991, 179, 713–719.

- Takada, A.; Ohmori, K.; Yoneda, T.; Tsuyuoka, K.; Hasegawa, A.; Kiso, M.; Kannagi, R. Contribution of carbohydrate antigens sialyl Lewis A and sialyl Lewis X to adhesion of human cancer cells to vascular endothelium. Cancer Res. 1993, 53, 354–361.

- Shimada, H.; Noie, T.; Ohashi, M.; Oba, K.; Takahashi, Y. Clinical significance of serum tumor markers for gastric cancer: A systematic review of literature by the Task Force of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Gastric Cancer 2014, 17, 26–33.

- Del Villano, B.C.; Brennan, S.; Brock, P.; Bucher, C.; Liu, V.; McClure, M.; Rake, B.; Space, S.; Westrick, B.; Schoemaker, H.; et al. Radioimmunometric assay for a monoclonal antibody-defined tumor marker, CA 19-9. Clin. Chem. 1983, 29, 549–552.

- Sato, T.; Nishimura, G.; Nonomura, A.; Miwa, K.; Miyazaki, I. Serological studies on CEA, CA 19-9, STn and SLX in colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 1999, 46, 914–919.

- Nakagoe, T.; Sawai, T.; Tsuji, T.; Jibiki, M.; Ohbatake, M.; Nanashima, A.; Yamaguchi, H.; Yasutake, T.; Ayabe, H.; Arisawa, K. Prognostic value of serum sialyl Lewis(a), sialyl Lewis(x) and sialyl Tn antigens in blood from the tumor drainage vein of colorectal cancer patients. Tumour. Biol. 2001, 22, 115–122.

- Nakagoe, T.; Sawai, T.; Tsuji, T.; Jibiki, M.; Nanashima, A.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kurosaki, N.; Yasutake, T.; Ayabe, H. Circulating sialyl Lewis(x), sialyl Lewis(a), and sialyl Tn antigens in colorectal cancer patients: Multivariate analysis of predictive factors for serum antigen levels. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 36, 166–172.

- Nakagoe, T.; Sawai, T.; Tsuji, T.; Jibiki, M.A.; Nanashima, A.; Yamaguchi, H.; Yasutake, T.; Kurosaki, N.; Ayabe, H.; Arisawa, K. Preoperative serum levels of sialyl Lewis(a), sialyl Lewis(x), and sialyl Tn antigens as prognostic markers after curative resection for colorectal cancer. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2001, 25, 299–308.

- Goonetilleke, K.S.; Siriwardena, A.K. Systematic review of carbohydrate antigen (CA 19-9) as a biochemical marker in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 33, 266–270.

- Locker, G.Y.; Hamilton, S.; Harris, J.; Jessup, J.M.; Kemeny, N.; Macdonald, J.S.; Somerfield, M.R.; Hayes, D.F.; Bast, R.C., Jr.; Asco. ASCO 2006 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in gastrointestinal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5313–5327.

- Molina, V.; Visa, L.; Conill, C.; Navarro, S.; Escudero, J.M.; Auge, J.M.; Filella, X.; Lopez-Boado, M.A.; Ferrer, J.; Fernandez-Cruz, L.; et al. CA 19-9 in pancreatic cancer: Retrospective evaluation of patients with suspicion of pancreatic cancer. Tumour. Biol. 2012, 33, 799–807.

- Tang, H.; Singh, S.; Partyka, K.; Kletter, D.; Hsueh, P.; Yadav, J.; Ensink, E.; Bern, M.; Hostetter, G.; Hartman, D.; et al. Glycan motif profiling reveals plasma sialyl-lewis x elevations in pancreatic cancers that are negative for sialyl-lewis A. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2015, 14, 1323–1333.

- Ballehaninna, U.K.; Chamberlain, R.S. The clinical utility of serum CA 19-9 in the diagnosis, prognosis and management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An evidence based appraisal. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2012, 3, 105–119.

- Stiksma, J.; Grootendorst, D.C.; van der Linden, P.W. CA 19-9 as a marker in addition to CEA to monitor colorectal cancer. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2014, 13, 239–244.

- Partyka, K.; Maupin, K.A.; Brand, R.E.; Haab, B.B. Diverse monoclonal antibodies against the CA 19-9 antigen show variation in binding specificity with consequences for clinical interpretation. Proteomics 2012, 12, 2212–2220.

- Kawa, S.; Oguchi, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Tokoo, M.; Furuta, S.; Kanai, M.; Homma, T. Elevated serum levels of Dupan-2 in pancreatic cancer patients negative for Lewis blood group phenotype. Br. J. Cancer 1991, 64, 899–902.

- Kawa, S.; Tokoo, M.; Oguchi, H.; Furuta, S.; Homma, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; Ogata, H.; Sakata, K. Epitope analysis of SPan-1 and DUPAN-2 using synthesized glycoconjugates sialyllact-N-fucopentaose II and sialyllact-N-tetraose. Pancreas 1994, 9, 692–697.

- Cakir, B.; Pankow, J.S.; Salomaa, V.; Couper, D.; Morris, T.L.; Brantley, K.R.; Hiller, K.M.; Heiss, G.; Weston, B.W. Distribution of Lewis (FUT3)genotype and allele: Frequencies in a biethnic United States population. Ann. Hematol. 2002, 81, 558–565.

- Takasaki, H.; Uchida, E.; Tempero, M.A.; Burnett, D.A.; Metzgar, R.S.; Pour, P.M. Correlative study on expression of CA 19-9 and DU-PAN-2 in tumor tissue and in serum of pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 1435–1438.

- Narimatsu, H.; Iwasaki, H.; Nakayama, F.; Ikehara, Y.; Kudo, T.; Nishihara, S.; Sugano, K.; Okura, H.; Fujita, S.; Hirohashi, S. Lewis and secretor gene dosages affect CA19-9 and DU-PAN-2 serum levels in normal individuals and colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 512–518.

- Sawabu, N.; Toya, D.; Takemori, Y.; Hattori, N.; Fukui, M. Measurement of a pancreatic cancer-associated antigen (DU-PAN-2) detected by a monoclonal antibody in sera of patients with digestive cancers. Int. J. Cancer 1986, 37, 693–696.

- Hakomori, S.I. Cell adhesion/recognition and signal transduction through glycosphingolipid microdomain. Glycoconj. J. 2000, 17, 143–151.

- Hakomori, S. Tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens defining tumor malignancy: Basis for development of anti-cancer vaccines. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2001, 491, 369–402.

- Lloyd, K.O.; Old, L.J. Human monoclonal antibodies to glycolipids and other carbohydrate antigens: Dissection of the humoral immune response in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 3445–3451.

- Yu, R.K.; Tsai, Y.T.; Ariga, T.; Yanagisawa, M. Structures, biosynthesis, and functions of gangliosides—An overview. J. Oleo Sci. 2011, 60, 537–544.

- Cao, S.; Hu, X.; Ren, S.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Wu, K.; Yang, Z.; Yang, W.; He, G.; Li, X. The biological role and immunotherapy of gangliosides and GD3 synthase in cancers. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1076862.

- Cahan, L.D.; Irie, R.F.; Singh, R.; Cassidenti, A.; Paulson, J.C. Identification of a human neuroectodermal tumor antigen (OFA-I-2) as ganglioside GD2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 7629–7633.

- Cavdarli, S.; Groux-Degroote, S.; Delannoy, P. Gangliosides: The Double-Edge Sword of Neuro-Ectodermal Derived Tumors. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 311.

- Ravindranath, M.H.; Tsuchida, T.; Morton, D.L.; Irie, R.F. Ganglioside GM3:GD3 ratio as an index for the management of melanoma. Cancer 1991, 67, 3029–3035.

- Hakomori, S.; Igarashi, Y. Gangliosides and glycosphingolipids as modulators of cell growth, adhesion, and transmembrane signaling. Adv. Lipid Res. 1993, 25, 147–162.

- Yoshida, S.; Fukumoto, S.; Kawaguchi, H.; Sato, S.; Ueda, R.; Furukawa, K. Ganglioside G(D2) in small cell lung cancer cell lines: Enhancement of cell proliferation and mediation of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4244–4252.

- Furukawa, K.; Hamamura, K.; Ohkawa, Y.; Ohmi, Y.; Furukawa, K. Disialyl gangliosides enhance tumor phenotypes with differential modalities. Glycoconj. J. 2012, 29, 579–584.

- Esaki, N.; Ohkawa, Y.; Hashimoto, N.; Tsuda, Y.; Ohmi, Y.; Bhuiyan, R.H.; Kotani, N.; Honke, K.; Enomoto, A.; Takahashi, M.; et al. ASC amino acid transporter 2, defined by enzyme-mediated activation of radical sources, enhances malignancy of GD2-positive small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 141–153.

- Ohmi, Y.; Kambe, M.; Ohkawa, Y.; Hamamura, K.; Tajima, O.; Takeuchi, R.; Furukawa, K.; Furukawa, K. Differential roles of gangliosides in malignant properties of melanomas. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206881.

- Iwasawa, T.; Zhang, P.; Ohkawa, Y.; Momota, H.; Wakabayashi, T.; Ohmi, Y.; Bhuiyan, R.H.; Furukawa, K.; Furukawa, K. Enhancement of malignant properties of human glioma cells by ganglioside GD3/GD2. Int. J. Oncol. 2018, 52, 1255–1266.

- Ohkawa, Y.; Zhang, P.; Momota, H.; Kato, A.; Hashimoto, N.; Ohmi, Y.; Bhuiyan, R.H.; Farhana, Y.; Natsume, A.; Wakabayashi, T.; et al. Lack of GD3 synthase (St8sia1) attenuates malignant properties of gliomas in genetically engineered mouse model. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 3756–3768.

- Zhang, P.; Ohkawa, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Momota, H.; Kato, A.; Kaneko, K.; Natsume, A.; Farhana, Y.; Ohmi, Y.; Okajima, T.; et al. St8sia1-deficiency in mice alters tumor environments of gliomas, leading to reduced disease severity. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 535–549.

- Yesmin, F.; Bhuiyan, R.H.; Ohmi, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Kaneko, K.; Ohkawa, Y.; Zhang, P.; Hamamura, K.; Cheung, N.V.; Kotani, N.; et al. Ganglioside GD2 Enhances the Malignant Phenotypes of Melanoma Cells by Cooperating with Integrins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 423.

- Caldwell, S.; Heitger, A.; Shen, W.; Liu, Y.; Taylor, B.; Ladisch, S. Mechanisms of ganglioside inhibition of APC function. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 1676–1683.

- Shurin, G.V.; Shurin, M.R.; Bykovskaia, S.; Shogan, J.; Lotze, M.T.; Barksdale, E.M., Jr. Neuroblastoma-derived gangliosides inhibit dendritic cell generation and function. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 363–369.

- Theruvath, J.; Menard, M.; Smith, B.A.H.; Linde, M.H.; Coles, G.L.; Dalton, G.N.; Wu, W.; Kiru, L.; Delaidelli, A.; Sotillo, E.; et al. Anti-GD2 synergizes with CD47 blockade to mediate tumor eradication. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 333–344.

- Schnaar, R.L. Gangliosides as Siglec ligands. Glycoconj. J. 2023, 40, 159–167.

- Nazha, B.; Inal, C.; Owonikoko, T.K. Disialoganglioside GD2 Expression in Solid Tumors and Role as a Target for Cancer Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1000.

- Cheung, N.K.; Saarinen, U.M.; Neely, J.E.; Landmeier, B.; Donovan, D.; Coccia, P.F. Monoclonal antibodies to a glycolipid antigen on human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1985, 45, 2642–2649.

- Mujoo, K.; Cheresh, D.A.; Yang, H.M.; Reisfeld, R.A. Disialoganglioside GD2 on human neuroblastoma cells: Target antigen for monoclonal antibody-mediated cytolysis and suppression of tumor growth. Cancer Res. 1987, 47, 1098–1104.

- Fukuda, M.; Horibe, K.; Furukawa, K. Enhancement of in vitro and in vivo anti-tumor activity of anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody 220-51 against human neuroblastoma by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Int. J. Mol. Med. 1998, 2, 471–475.

- Nakamura, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Shitara, K.; Hanai, N. Construction of humanized anti-ganglioside monoclonal antibodies with potent immune effector functions. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2001, 50, 275–284.

- Imai, M.; Landen, C.; Ohta, R.; Cheung, N.K.; Tomlinson, S. Complement-mediated mechanisms in anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody therapy of murine metastatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 10562–10568.

- Modak, S.; Cheung, N.K. Disialoganglioside directed immunotherapy of neuroblastoma. Cancer Invest. 2007, 25, 67–77.

- Aixinjueluo, W.; Furukawa, K.; Zhang, Q.; Hamamura, K.; Tokuda, N.; Yoshida, S.; Ueda, R.; Furukawa, K. Mechanisms for the apoptosis of small cell lung cancer cells induced by anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies: Roles of anoikis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 29828–29836.

- Furukawa, K.; Hamamura, K.; Aixinjueluo, W.; Furukawa, K. Biosignals modulated by tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens: Novel targets for cancer therapy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1086, 185–198.

- Dhillon, S. Dinutuximab: First global approval. Drugs 2015, 75, 923–927.

- Mueller, B.M.; Romerdahl, C.A.; Gillies, S.D.; Reisfeld, R.A. Enhancement of antibody-dependent cytotoxicity with a chimeric anti-GD2 antibody. J. Immunol. 1990, 144, 1382–1386.

- Yu, A.L.; Gilman, A.L.; Ozkaynak, M.F.; London, W.B.; Kreissman, S.G.; Chen, H.X.; Smith, M.; Anderson, B.; Villablanca, J.G.; Matthay, K.K.; et al. Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for neuroblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1324–1334.

- Mabe, N.W.; Huang, M.; Dalton, G.N.; Alexe, G.; Schaefer, D.A.; Geraghty, A.C.; Robichaud, A.L.; Conway, A.S.; Khalid, D.; Mader, M.M.; et al. Transition to a mesenchymal state in neuroblastoma confers resistance to anti-GD2 antibody via reduced expression of ST8SIA1. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 976–993.

- Osenga, K.L.; Hank, J.A.; Albertini, M.R.; Gan, J.; Sternberg, A.G.; Eickhoff, J.; Seeger, R.C.; Matthay, K.K.; Reynolds, C.P.; Twist, C.; et al. A phase I clinical trial of the hu14.18-IL2 (EMD 273063) as a treatment for children with refractory or recurrent neuroblastoma and melanoma: A study of the Children’s Oncology Group. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 1750–1759.

- Delgado, D.C.; Hank, J.A.; Kolesar, J.; Lorentzen, D.; Gan, J.; Seo, S.; Kim, K.; Shusterman, S.; Gillies, S.D.; Reisfeld, R.A.; et al. Genotypes of NK cell KIR receptors, their ligands, and Fcgamma receptors in the response of neuroblastoma patients to Hu14.18-IL2 immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 9554–9561.

- Shusterman, S.; London, W.B.; Gillies, S.D.; Hank, J.A.; Voss, S.D.; Seeger, R.C.; Reynolds, C.P.; Kimball, J.; Albertini, M.R.; Wagner, B.; et al. Antitumor activity of hu14.18-IL2 in patients with relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma: A Children’s Oncology Group (COG) phase II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4969–4975.

- Albertini, M.R.; Hank, J.A.; Gadbaw, B.; Kostlevy, J.; Haldeman, J.; Schalch, H.; Gan, J.; Kim, K.; Eickhoff, J.; Gillies, S.D.; et al. Phase II trial of hu14.18-IL2 for patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2012, 61, 2261–2271.

- Ladenstein, R.; Potschger, U.; Valteau-Couanet, D.; Luksch, R.; Castel, V.; Yaniv, I.; Laureys, G.; Brock, P.; Michon, J.M.; Owens, C.; et al. Interleukin 2 with anti-GD2 antibody ch14.18/CHO (dinutuximab beta) in patients with high-risk neuroblastoma (HR-NBL1/SIOPEN): A multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 1617–1629.

- Cheung, N.K.; Cheung, I.Y.; Kushner, B.H.; Ostrovnaya, I.; Chamberlain, E.; Kramer, K.; Modak, S. Murine anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody 3F8 combined with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and 13-cis-retinoic acid in high-risk patients with stage 4 neuroblastoma in first remission. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3264–3270.

- Cheung, I.Y.; Kushner, B.H.; Modak, S.; Basu, E.M.; Roberts, S.S.; Cheung, N.V. Phase I trial of anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody hu3F8 plus GM-CSF: Impact of body weight, immunogenicity and anti-GD2 response on pharmacokinetics and survival. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1358331.

- Kushner, B.H.; Cheung, I.Y.; Modak, S.; Basu, E.M.; Roberts, S.S.; Cheung, N.K. Humanized 3F8 Anti-GD2 Monoclonal Antibody Dosing With Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor in Patients With Resistant Neuroblastoma: A Phase 1 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1729–1735.

- Cheng, M.; Ahmed, M.; Xu, H.; Cheung, N.K. Structural design of disialoganglioside GD2 and CD3-bispecific antibodies to redirect T cells for tumor therapy. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 476–486.

- Cheever, M.A.; Allison, J.P.; Ferris, A.S.; Finn, O.J.; Hastings, B.M.; Hecht, T.T.; Mellman, I.; Prindiville, S.A.; Viner, J.L.; Weiner, L.M.; et al. The prioritization of cancer antigens: A national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 5323–5337.

- Riley, N.M.; Wen, R.M.; Bertozzi, C.R.; Brooks, J.D.; Pitteri, S.J. Measuring the multifaceted roles of mucin-domain glycoproteins in cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2023, 157, 83–121.

- Kufe, D.W. Mucins in cancer: Function, prognosis and therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 874–885.

- Duffy, M.J.; Duggan, C.; Keane, R.; Hill, A.D.; McDermott, E.; Crown, J.; O’Higgins, N. High preoperative CA 15-3 concentrations predict adverse outcome in node-negative and node-positive breast cancer: Study of 600 patients with histologically confirmed breast cancer. Clin. Chem. 2004, 50, 559–563.

- Duffy, M.J.; Shering, S.; Sherry, F.; McDermott, E.; O’Higgins, N. CA 15-3: A prognostic marker in breast cancer. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2000, 15, 330–333.

- Canney, P.A.; Moore, M.; Wilkinson, P.M.; James, R.D. Ovarian cancer antigen CA125: A prospective clinical assessment of its role as a tumour marker. Br. J. Cancer 1984, 50, 765–769.

- Hollingsworth, M.A.; Swanson, B.J. Mucins in cancer: Protection and control of the cell surface. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 45–60.

- Taylor-Papadimitriou, J.; Burchell, J.M.; Graham, R.; Beatson, R. Latest developments in MUC1 immunotherapy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 659–668.

- Aithal, A.; Rauth, S.; Kshirsagar, P.; Shah, A.; Lakshmanan, I.; Junker, W.M.; Jain, M.; Ponnusamy, M.P.; Batra, S.K. MUC16 as a novel target for cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2018, 22, 675–686.

- Chan, A.K.; Lockhart, D.C.; von Bernstorff, W.; Spanjaard, R.A.; Joo, H.G.; Eberlein, T.J.; Goedegebuure, P.S. Soluble MUC1 secreted by human epithelial cancer cells mediates immune suppression by blocking T-cell activation. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 82, 721–726.

- Agrawal, B.; Krantz, M.J.; Parker, J.; Longenecker, B.M. Expression of MUC1 mucin on activated human T cells: Implications for a role of MUC1 in normal immune regulation. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 4079–4081.

- Tempero, R.M.; VanLith, M.L.; Morikane, K.; Rowse, G.J.; Gendler, S.J.; Hollingsworth, M.A. CD4+ lymphocytes provide MUC1-specific tumor immunity in vivo that is undetectable in vitro and is absent in MUC1 transgenic mice. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 5500–5506.

- Burchell, J.; Gendler, S.; Taylor-Papadimitriou, J.; Girling, A.; Lewis, A.; Millis, R.; Lamport, D. Development and characterization of breast cancer reactive monoclonal antibodies directed to the core protein of the human milk mucin. Cancer Res. 1987, 47, 5476–5482.

- Girling, A.; Bartkova, J.; Burchell, J.; Gendler, S.; Gillett, C.; Taylor-Papadimitriou, J. A core protein epitope of the polymorphic epithelial mucin detected by the monoclonal antibody SM-3 is selectively exposed in a range of primary carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer 1989, 43, 1072–1076.

- Taylor-Papadimitriou, J.; Peterson, J.A.; Arklie, J.; Burchell, J.; Ceriani, R.L.; Bodmer, W.F. Monoclonal antibodies to epithelium-specific components of the human milk fat globule membrane: Production and reaction with cells in culture. Int. J. Cancer 1981, 28, 17–21.

- Qi, W.; Schultes, B.C.; Liu, D.; Kuzma, M.; Decker, W.; Madiyalakan, R. Characterization of an anti-MUC1 monoclonal antibody with potential as a cancer vaccine. Hybrid Hybridomics 2001, 20, 313–324.

- Martinez-Saez, N.; Castro-Lopez, J.; Valero-Gonzalez, J.; Madariaga, D.; Companon, I.; Somovilla, V.J.; Salvado, M.; Asensio, J.L.; Jimenez-Barbero, J.; Avenoza, A.; et al. Deciphering the Non-Equivalence of Serine and Threonine O-Glycosylation Points: Implications for Molecular Recognition of the Tn Antigen by an anti-MUC1 Antibody. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 9830–9834.

- Karsten, U.; Serttas, N.; Paulsen, H.; Danielczyk, A.; Goletz, S. Binding patterns of DTR-specific antibodies reveal a glycosylation-conditioned tumor-specific epitope of the epithelial mucin (MUC1). Glycobiology 2004, 14, 681–692.

- Movahedin, M.; Brooks, T.M.; Supekar, N.T.; Gokanapudi, N.; Boons, G.J.; Brooks, C.L. Glycosylation of MUC1 influences the binding of a therapeutic antibody by altering the conformational equilibrium of the antigen. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 677–687.

- de Bono, J.S.; Rha, S.Y.; Stephenson, J.; Schultes, B.C.; Monroe, P.; Eckhardt, G.S.; Hammond, L.A.; Whiteside, T.L.; Nicodemus, C.F.; Cermak, J.M.; et al. Phase I trial of a murine antibody to MUC1 in patients with metastatic cancer: Evidence for the activation of humoral and cellular antitumor immunity. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 1825–1833.

- Guerrero-Ochoa, P.; Ibanez-Perez, R.; Berbegal-Pinilla, G.; Aguilar, D.; Marzo, I.; Corzana, F.; Minjarez-Saenz, M.; Macias-Leon, J.; Conde, B.; Raso, J.; et al. Preclinical Studies of Granulysin-Based Anti-MUC1-Tn Immunotoxins as a New Antitumoral Treatment. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1223.

- Danielczyk, A.; Stahn, R.; Faulstich, D.; Loffler, A.; Marten, A.; Karsten, U.; Goletz, S. PankoMab: A potent new generation anti-tumour MUC1 antibody. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2006, 55, 1337–1347.

- Fiedler, W.; DeDosso, S.; Cresta, S.; Weidmann, J.; Tessari, A.; Salzberg, M.; Dietrich, B.; Baumeister, H.; Goletz, S.; Gianni, L.; et al. A phase I study of PankoMab-GEX, a humanised glyco-optimised monoclonal antibody to a novel tumour-specific MUC1 glycopeptide epitope in patients with advanced carcinomas. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 63, 55–63.

- Ledermann, J.A.; Zurawski, B.; Raspagliesi, F.; De Giorgi, U.; Arranz Arija, J.; Romeo Marin, M.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Poka, R.L.; Markowska, J.; Cebotaru, C.; et al. Maintenance therapy of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma with the anti-tumor-associated-mucin-1 antibody gatipotuzumab: Results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, phase II study. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100311.

- Posey, A.D., Jr.; Schwab, R.D.; Boesteanu, A.C.; Steentoft, C.; Mandel, U.; Engels, B.; Stone, J.D.; Madsen, T.D.; Schreiber, K.; Haines, K.M.; et al. Engineered CAR T Cells Targeting the Cancer-Associated Tn-Glycoform of the Membrane Mucin MUC1 Control Adenocarcinoma. Immunity 2016, 44, 1444–1454.

- Maher, J.; Wilkie, S.; Davies, D.M.; Arif, S.; Picco, G.; Julien, S.; Foster, J.; Burchell, J.; Taylor-Papadimitriou, J. Targeting of Tumor-Associated Glycoforms of MUC1 with CAR T Cells. Immunity 2016, 45, 945–946.

- Wei, X.; Lai, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Li, B.; Lin, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, Q.; et al. PSCA and MUC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer as targets of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1284722.

- Dharma Rao, T.; Park, K.J.; Smith-Jones, P.; Iasonos, A.; Linkov, I.; Soslow, R.A.; Spriggs, D.R. Novel monoclonal antibodies against the proximal (carboxy-terminal) portions of MUC16. Appl Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2010, 18, 462–472.

- Chekmasova, A.A.; Rao, T.D.; Nikhamin, Y.; Park, K.J.; Levine, D.A.; Spriggs, D.R.; Brentjens, R.J. Successful eradication of established peritoneal ovarian tumors in SCID-Beige mice following adoptive transfer of T cells genetically targeted to the MUC16 antigen. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3594–3606.

- Yeku, O.O.; Purdon, T.J.; Koneru, M.; Spriggs, D.; Brentjens, R.J. Armored CAR T cells enhance antitumor efficacy and overcome the tumor microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10541.

- Rafiq, S.; Yeku, O.O.; Jackson, H.J.; Purdon, T.J.; van Leeuwen, D.G.; Drakes, D.J.; Song, M.; Miele, M.M.; Li, Z.; Wang, P.; et al. Targeted delivery of a PD-1-blocking scFv by CAR-T cells enhances anti-tumor efficacy in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 847–856.

- Yeku, O.O.; Rao, T.D.; Laster, I.; Kononenko, A.; Purdon, T.J.; Wang, P.; Cui, Z.; Liu, H.; Brentjens, R.J.; Spriggs, D. Bispecific T-Cell Engaging Antibodies Against MUC16 Demonstrate Efficacy Against Ovarian Cancer in Monotherapy and in Combination With PD-1 and VEGF Inhibition. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 663379.

- Liu, J.F.; Moore, K.N.; Birrer, M.J.; Berlin, S.; Matulonis, U.A.; Infante, J.R.; Wolpin, B.; Poon, K.A.; Firestein, R.; Xu, J.; et al. Phase I study of safety and pharmacokinetics of the anti-MUC16 antibody-drug conjugate DMUC5754A in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer or unresectable pancreatic cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 2124–2130.

- Chen, Y.; Clark, S.; Wong, T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dennis, M.S.; Luis, E.; Zhong, F.; Bheddah, S.; Koeppen, H.; et al. Armed antibodies targeting the mucin repeats of the ovarian cancer antigen, MUC16, are highly efficacious in animal tumor models. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 4924–4932.

- Reinsberg, J.; Heydweiller, A.; Wagner, U.; Pfeil, K.; Oehr, P.; Krebs, D. Evidence for interaction of human anti-idiotypic antibodies with CA 125 determination in a patient after radioimmunodetection. Clin. Chem 1990, 36, 164–167.

- Capstick, V.; Maclean, G.D.; Suresh, M.R.; Bodnar, D.; Lloyd, S.; Shepert, L.; Longenecker, B.M.; Krantz, M. Clinical evaluation of a new two-site assay for CA125 antigen. Int. J. Biol. Markers 1991, 6, 129–135.

- Brewer, M.; Angioli, R.; Scambia, G.; Lorusso, D.; Terranova, C.; Panici, P.B.; Raspagliesi, F.; Scollo, P.; Plotti, F.; Ferrandina, G.; et al. Front-line chemo-immunotherapy with carboplatin-paclitaxel using oregovomab indirect immunization in advanced ovarian cancer: A randomized phase II study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 156, 523–529.

- Battaglia, A.; Buzzonetti, A.; Fossati, M.; Scambia, G.; Fattorossi, A.; Madiyalakan, M.R.; Mahnke, Y.D.; Nicodemus, C. Translational immune correlates of indirect antibody immunization in a randomized phase II study using scheduled combination therapy with carboplatin/paclitaxel plus oregovomab in ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 383–397.

- Hammarstrom, S. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family: Structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1999, 9, 67–81.

- Stamey, T.A.; Yang, N.; Hay, A.R.; McNeal, J.E.; Freiha, F.S.; Redwine, E. Prostate-specific antigen as a serum marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 909–916.

- Thompson, I.M.; Pauler, D.K.; Goodman, P.J.; Tangen, C.M.; Lucia, M.S.; Parnes, H.L.; Minasian, L.M.; Ford, L.G.; Lippman, S.M.; Crawford, E.D.; et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level < or =4.0 ng per milliliter. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2239–2246.

- Heptner, G.; Domschke, S.; Domschke, W. Comparison of CA 72-4 with CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen in the serodiagnostics of gastrointestinal malignancies. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1989, 24, 745–750.

- Schroder, F.H.; Hugosson, J.; Roobol, M.J.; Tammela, T.L.; Ciatto, S.; Nelen, V.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Lujan, M.; Lilja, H.; Zappa, M.; et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1320–1328.

- Hernandez, J.; Thompson, I.M. Prostate-specific antigen: A review of the validation of the most commonly used cancer biomarker. Cancer 2004, 101, 894–904.

- Moyer, V.A. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 120–134.

- Beauchemin, N.; Arabzadeh, A. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules (CEACAMs) in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013, 32, 643–671.

- Nicholson, B.D.; Shinkins, B.; Pathiraja, I.; Roberts, N.W.; James, T.J.; Mallett, S.; Perera, R.; Primrose, J.N.; Mant, D. Blood CEA levels for detecting recurrent colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD011134.

- Becerra, A.Z.; Probst, C.P.; Tejani, M.A.; Aquina, C.T.; Gonzalez, M.G.; Hensley, B.J.; Noyes, K.; Monson, J.R.; Fleming, F.J. Evaluating the Prognostic Role of Elevated Preoperative Carcinoembryonic Antigen Levels in Colon Cancer Patients: Results from the National Cancer Database. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 1554–1561.

- Desai, S.; Guddati, A.K. Carcinoembryonic Antigen, Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9, Cancer Antigen 125, Prostate-Specific Antigen and Other Cancer Markers: A Primer on Commonly Used Cancer Markers. World J. Oncol. 2023, 14, 4–14.

- Decary, S.; Berne, P.F.; Nicolazzi, C.; Lefebvre, A.M.; Dabdoubi, T.; Cameron, B.; Rival, P.; Devaud, C.; Prades, C.; Bouchard, H.; et al. Preclinical Activity of SAR408701: A Novel Anti-CEACAM5-maytansinoid Antibody-drug Conjugate for the Treatment of CEACAM5-positive Epithelial Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 6589–6599.

- Blumenthal, R.D.; Hansen, H.J.; Goldenberg, D.M. Inhibition of adhesion, invasion, and metastasis by antibodies targeting CEACAM6 (NCA-90) and CEACAM5 (Carcinoembryonic Antigen). Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 8809–8817.

- Jessup, J.M.; Kim, J.C.; Thomas, P.; Ishii, S.; Ford, R.; Shively, J.E.; Durbin, H.; Stanners, C.P.; Fuks, A.; Zhou, H.; et al. Adhesion to carcinoembryonic antigen by human colorectal carcinoma cells involves at least two epitopes. Int. J. Cancer 1993, 55, 262–268.

- Sharkey, R.M.; Juweid, M.; Shevitz, J.; Behr, T.; Dunn, R.; Swayne, L.C.; Wong, G.Y.; Blumenthal, R.D.; Griffiths, G.L.; Siegel, J.A.; et al. Evaluation of a complementarity-determining region-grafted (humanized) anti-carcinoembryonic antigen monoclonal antibody in preclinical and clinical studies. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 5935s–5945s.

- Dotan, E.; Cohen, S.J.; Starodub, A.N.; Lieu, C.H.; Messersmith, W.A.; Simpson, P.S.; Guarino, M.J.; Marshall, J.L.; Goldberg, R.M.; Hecht, J.R.; et al. Phase I/II Trial of Labetuzumab Govitecan (Anti-CEACAM5/SN-38 Antibody-Drug Conjugate) in Patients With Refractory or Relapsing Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3338–3346.

- Peracaula, R.; Tabares, G.; Royle, L.; Harvey, D.J.; Dwek, R.A.; Rudd, P.M.; de Llorens, R. Altered glycosylation pattern allows the distinction between prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from normal and tumor origins. Glycobiology 2003, 13, 457–470.

- Alpert, P.F. New Evidence for the Benefit of Prostate-specific Antigen Screening: Data From 400,887 Kaiser Permanente Patients. Urology 2018, 118, 119–126.

- Etzioni, R.; Tsodikov, A.; Mariotto, A.; Szabo, A.; Falcon, S.; Wegelin, J.; DiTommaso, D.; Karnofski, K.; Gulati, R.; Penson, D.F.; et al. Quantifying the role of PSA screening in the US prostate cancer mortality decline. Cancer Causes Control 2008, 19, 175–181.

- Gulley, J.L.; Borre, M.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Ng, S.; Agarwal, N.; Parker, C.C.; Pook, D.W.; Rathenborg, P.; Flaig, T.W.; Carles, J.; et al. Phase III Trial of PROSTVAC in Asymptomatic or Minimally Symptomatic Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1051–1061.

- Rehman, L.U.; Nisar, M.H.; Fatima, W.; Sarfraz, A.; Azeem, N.; Sarfraz, Z.; Robles-Velasco, K.; Cherrez-Ojeda, I. Immunotherapy for Prostate Cancer: A Current Systematic Review and Patient Centric Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1446.

- Peixoto, A.; Relvas-Santos, M.; Azevedo, R.; Santos, L.L.; Ferreira, J.A. Protein Glycosylation and Tumor Microenvironment Alterations Driving Cancer Hallmarks. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 380.

- Smith, B.A.H.; Bertozzi, C.R. The clinical impact of glycobiology: Targeting selectins, Siglecs and mammalian glycans. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 217–243.

- RodrIguez, E.; Schetters, S.T.T.; van Kooyk, Y. The tumour glyco-code as a novel immune checkpoint for immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 204–211.

- Xiao, H.; Woods, E.C.; Vukojicic, P.; Bertozzi, C.R. Precision glycocalyx editing as a strategy for cancer immunotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10304–10309.

- Gray, M.A.; Stanczak, M.A.; Mantuano, N.R.; Xiao, H.; Pijnenborg, J.F.A.; Malaker, S.A.; Miller, C.L.; Weidenbacher, P.A.; Tanzo, J.T.; Ahn, G.; et al. Targeted glycan degradation potentiates the anticancer immune response in vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 1376–1384.

- Ley, K.; Kansas, G.S. Selectins in T-cell recruitment to non-lymphoid tissues and sites of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 325–335.

- Tinoco, R.; Carrette, F.; Barraza, M.L.; Otero, D.C.; Magana, J.; Bosenberg, M.W.; Swain, S.L.; Bradley, L.M. PSGL-1 Is an Immune Checkpoint Regulator that Promotes T Cell Exhaustion. Immunity 2016, 44, 1470.

- Johnston, R.J.; Su, L.J.; Pinckney, J.; Critton, D.; Boyer, E.; Krishnakumar, A.; Corbett, M.; Rankin, A.L.; Dibella, R.; Campbell, L.; et al. VISTA is an acidic pH-selective ligand for PSGL-1. Nature 2019, 574, 565–570.

- Tagliamento, M.; Bironzo, P.; Novello, S. New emerging targets in cancer immunotherapy: The role of VISTA. ESMO Open 2020, 4, e000683.

- DeAngelo, D.J.; Jonas, B.A.; Liesveld, J.L.; Bixby, D.L.; Advani, A.S.; Marlton, P.; Magnani, J.L.; Thackray, H.M.; Feldman, E.J.; O’Dwyer, M.E.; et al. Phase 1/2 study of uproleselan added to chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2022, 139, 1135–1146.

- Muz, B.; Abdelghafer, A.; Markovic, M.; Yavner, J.; Melam, A.; Salama, N.N.; Azab, A.K. Targeting E-selectin to Tackle Cancer Using Uproleselan. Cancers 2021, 13, 335.

- Kantarjian, H.M.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Stelljes, M.; Martinelli, G.; Liedtke, M.; Stock, W.; Gokbuget, N.; O’Brien, S.; Wang, K.; Wang, T.; et al. Inotuzumab Ozogamicin versus Standard Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 740–753.

- Castaigne, S.; Pautas, C.; Terre, C.; Raffoux, E.; Bordessoule, D.; Bastie, J.N.; Legrand, O.; Thomas, X.; Turlure, P.; Reman, O.; et al. Effect of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on survival of adult patients with de-novo acute myeloid leukaemia (ALFA-0701): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2012, 379, 1508–1516.

- Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, L.N.; Flies, D.B.; Nie, X.; Toki, M.; Zhang, J.; Song, C.; Zarr, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. Siglec-15 as an immune suppressor and potential target for normalization cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 656–666.

- Modenutti, C.P.; Capurro, J.I.B.; Di Lella, S.; Marti, M.A. The Structural Biology of Galectin-Ligand Recognition: Current Advances in Modeling Tools, Protein Engineering, and Inhibitor Design. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 823.

- Thiemann, S.; Baum, L.G. Galectins and Immune Responses-Just How Do They Do Those Things They Do? Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 34, 243–264.

- Zhang, J.; Larrocha, P.S.; Zhang, B.; Wainwright, D.; Dhar, P.; Wu, J.D. Antibody targeting tumor-derived soluble NKG2D ligand sMIC provides dual co-stimulation of CD8 T cells and enables sMIC(+) tumors respond to PD1/PD-L1 blockade therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 223.

- Zou, Y.; Luo, W.; Guo, J.; Luo, Q.; Deng, M.; Lu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, C.C. NK cell-mediated anti-leukemia cytotoxicity is enhanced using a NKG2D ligand MICA and anti-CD20 scfv chimeric protein. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018, 48, 1750–1763.

- Ding, H.; Yang, X.; Wei, Y. Fusion Proteins of NKG2D/NKG2DL in Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 177.

- Hu, B.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, H.; Qi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Chang, Y.; Bai, Q.; Xia, Y.; et al. Blockade of DC-SIGN(+) Tumor-Associated Macrophages Reactivates Antitumor Immunity and Improves Immunotherapy in Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1707–1719.