| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Christian Battipaglia | -- | 1739 | 2023-06-30 23:55:15 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 1739 | 2023-07-03 03:28:50 | | |

Video Upload Options

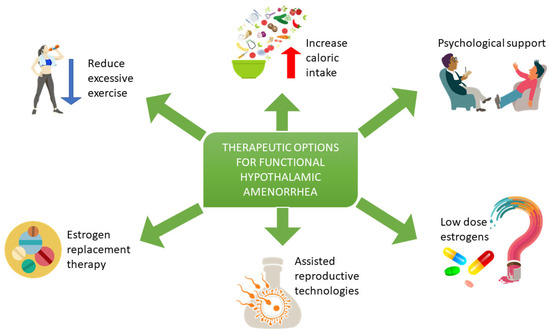

Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA) is a non-organic reversible chronic endocrine disorder characterized by an impaired pulsatile secretion of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. This impaired secretion, triggered by psychosocial and metabolic stressors, leads to an abnormal pituitary production of gonadotropins. As LH and FSH release is defective, the ovarian function is steadily reduced, inducing a systemic hypoestrogenic condition characterized by amenorrhea, vaginal atrophy, mood changes and increased risk of osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. Diagnosis of FHA is made excluding other possible causes for secondary amenorrhea, and it is based upon the findings of low serum gonadotropins and estradiol (E2) with evidence of precipitating factors (excessive exercise, low weight, stress). Treatments of women with FHA include weight gain through an appropriate diet and physical activity reduction, psychological support, and integrative approach up to estrogen replacement therapy.

1. Introduction

2. Diagnosis of FHA

3. Treatment of Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea

References

- Meczekalski, B.; Niwczyk, O.; Bala, G.; Szeliga, A. Stress, kisspeptin, and functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2022, 67, 102288.

- Marshall, L.A. Clinical evaluation of amenorrhea in active and athletic women. Clin. Sports Med. 1994, 13, 371–387.

- Morrison, A.E.; Fleming, S.; Levy, M.J. A review of the pathophysiology of functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea in women subject to psychological stress, disordered eating, excessive exercise or a combination of these factors. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021, 95, 229–238.

- Nattiv, A.; Loucks, A.B.; Manore, M.M.; Sanborn, C.F.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Warren, M.P. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 1867–1882.

- Ryterska, K.; Kordek, A.; Załęska, P. Has Menstruation Disappeared? Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea—What Is This Story about? Nutrients 2021, 13, 2827.

- Genazzani, A.D.; Gastaldi, M.; Volpe, A.; Petraglia, F.; Genazzani, A.R. Spontaneous episodic release of adenohypophyseal hormones in hypothalamic amenorrhea. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 1995, 9, 325–334.

- Gordon, C.M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Berga, S.L.; Kaplan, J.R.; Mastorakos, G.; Misra, M.; Murad, M.H.; Santoro, N.F.; Warren, M.P. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 1413–1439.

- Fontana, L.; Garzia, E.; Marfia, G.; Galiano, V.; Miozzo, M. Epigenetics of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 953431.

- Laughlin, G.A.; Dominguez, C.E.; Yen, S.S. Nutritional and endocrine-metabolic aberrations in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 25–32.

- Meczekalski, B.; Katulski, K.; Czyzyk, A.; Podfigurna-Stopa, A.; Maciejewska-Jeske, M. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea and its influence on women’s health. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2014, 37, 1049–1056.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Current evaluation of amenorrhea. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 86 (Suppl. S1), S148–S155.

- Meczekalski, B.; Podfigurna-Stopa, A.; Warenik-Szymankiewicz, A.; Genazzani, A.R. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: Current view on neuroendocrine aberrations. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2008, 24, 4–11.

- Valdes-Socin, H.; Rubio Almanza, M.; Tomé Fernández-Ladreda, M.; Debray, F.G.; Bours, V.; Beckers, A. Reproduction, Smell, and Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Genetic Defects in Different Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadal Syndromes. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 109.

- Grinspoon, S.; Miller, K.; Coyle, C.; Krempin, J.; Armstrong, C.; Pitts, S.; Herzog, D.; Klibanski, A. Severity of osteopenia in estrogen-deficient women with anorexia nervosa and hypothalamic amenorrhea. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 2049–2055.

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine; Golden, N.H.; Katzman, D.K.; Sawyer, S.M.; Ornstein, R.M. Position Paper of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine: Medical management of restrictive eating disorders in adolescents and young adults. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015, 56, 121–125.

- Dempfle, A.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Timmesfeld, N.; Schwarte, R.; Egberts, K.M.; Pfeiffer, E.; Fleischhaker, C.; Wewetzer, C.; Bühren, K. Predictors of the resumption of menses in adolescent anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 308.

- Mountjoy, M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Burke, L.; Carter, S.; Constantini, N.; Lebrun, C.; Meyer, N.; Sherman, R.; Steffen, K.; Budgett, R.; et al. The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the Female Athlete Triad--Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 491–497.

- Golden, N.H.; Jacobson, M.S.; Schebendach, J.; Solanto, M.V.; Hertz, S.M.; Shenker, I.R. Resumption of menses in anorexia nervosa. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1997, 151, 16–21.

- Marcus, M.D.; Loucks, T.L.; Berga, S.L. Psychological correlates of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Fertil. Steril. 2001, 76, 310–316.

- Michopoulos, V.; Mancini, F.; Loucks, T.L.; Berga, S.L. Neuroendocrine recovery initiated by cognitive behavioral therapy in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: A randomized, controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 2084–2091.e1.

- Misra, M.; Katzman, D.; Miller, K.K.; Mendes, N.; Snelgrove, D.; Russell, M.; Goldstein, M.A.; Ebrahimi, S.; Clauss, L.; Weigel, T.; et al. Physiologic Estrogen Replacement Increases Bone Density in Adolescent Girls with Anorexia Nervosa. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 2430–2438.

- Warren, M.P.; Miller, K.K.; Olson, W.H.; Grinspoon, S.K.; Friedman, A.J. Effects of an oral contraceptive (norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol) on bone mineral density in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea and osteopenia: An open-label extension of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Contraception 2005, 72, 206–211.

- Kam, G.Y.; Leung, K.C.; Baxter, R.C.; Ho, K.K. Estrogens exert route- and dose-dependent effects on insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-3 and the acid-labile subunit of the IGF ternary complex. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 1918–1922.

- Santoro, N.; Wierman, M.E.; Filicori, M.; Waldstreicher, J.; Crowley, W.F. Intravenous administration of pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone in hypothalamic amenorrhea: Effects of dosage. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1986, 62, 109–116.

- Martin, K.; Santoro, N.; Hall, J.; Filicori, M.; Wierman, M.; Crowley, W.F. Clinical review 15: Management of ovulatory disorders with pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1990, 71, 1081A–1081G.

- Djurovic, M.; Pekić, S.; Petakov, M.; Damjanovic, S.; Doknic, M.; Diéguez, C.; Casanueva, F.F.; Popovic, V. Gonadotropin response to clomiphene and plasma leptin levels in weight recovered but amenorrhoeic patients with anorexia nervosa. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2004, 27, 523–527.

- Wakeling, A.; Marshall, J.C.; Beardwood, C.J.; Souza, V.F.; Russell, G.F. The effects of clomiphene citrate on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in anorexia nervosa. Psychol. Med. 1976, 6, 371–380.

- ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Nutrition and reproduction in women. Hum. Reprod. Update 2006, 12, 193–207.

- Tran, N.D.; Cedars, M.I.; Rosen, M.P. The role of anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) in assessing ovarian reserve. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 3609–3614.