Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Divakaran Pandian | -- | 1558 | 2023-06-27 15:19:53 | | | |

| 2 | Fanny Huang | Meta information modification | 1558 | 2023-06-29 07:44:01 | | | | |

| 3 | Fanny Huang | Meta information modification | 1558 | 2023-06-29 09:01:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Pandian, D.; Najer, T.; Modrý, D. Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the Definitive Rodent Host. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/46129 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Pandian D, Najer T, Modrý D. Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the Definitive Rodent Host. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/46129. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Pandian, Divakaran, Tomáš Najer, David Modrý. "Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the Definitive Rodent Host" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/46129 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Pandian, D., Najer, T., & Modrý, D. (2023, June 27). Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the Definitive Rodent Host. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/46129

Pandian, Divakaran, et al. "Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the Definitive Rodent Host." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 June, 2023.

Copy Citation

Human angiostrongylosis is an emerging zoonosis caused by the larvae of three species of metastrongyloid nematodes of the genus Angiostrongylus, with Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen, 1935) being dominant across the world. Its obligatory heteroxenous life cycle includes rats as definitive hosts, mollusks as intermediate hosts, and amphibians and reptiles as paratenic hosts. In humans, the infection manifests as Angiostrongylus eosinophilic meningitis (AEM) or ocular form.

human angiostrongyliasis

Indian subcontinent

Angiostrongylus cantonensis

1. Introduction

Angiostrongylus cantonensis is thought to be largely associated with three invasive species of Rattini: R. rattus, R. norvegicus, and R. exulans, with local involvement of a few other rodent hosts [1]. The frequency with which infection spreads to other rodent species is largely unknown. An infection of Sigmodon hispidus (Say & Ord, 1825), a rodent host in the rather distant family Cricetidae, has been reported in North America [2].

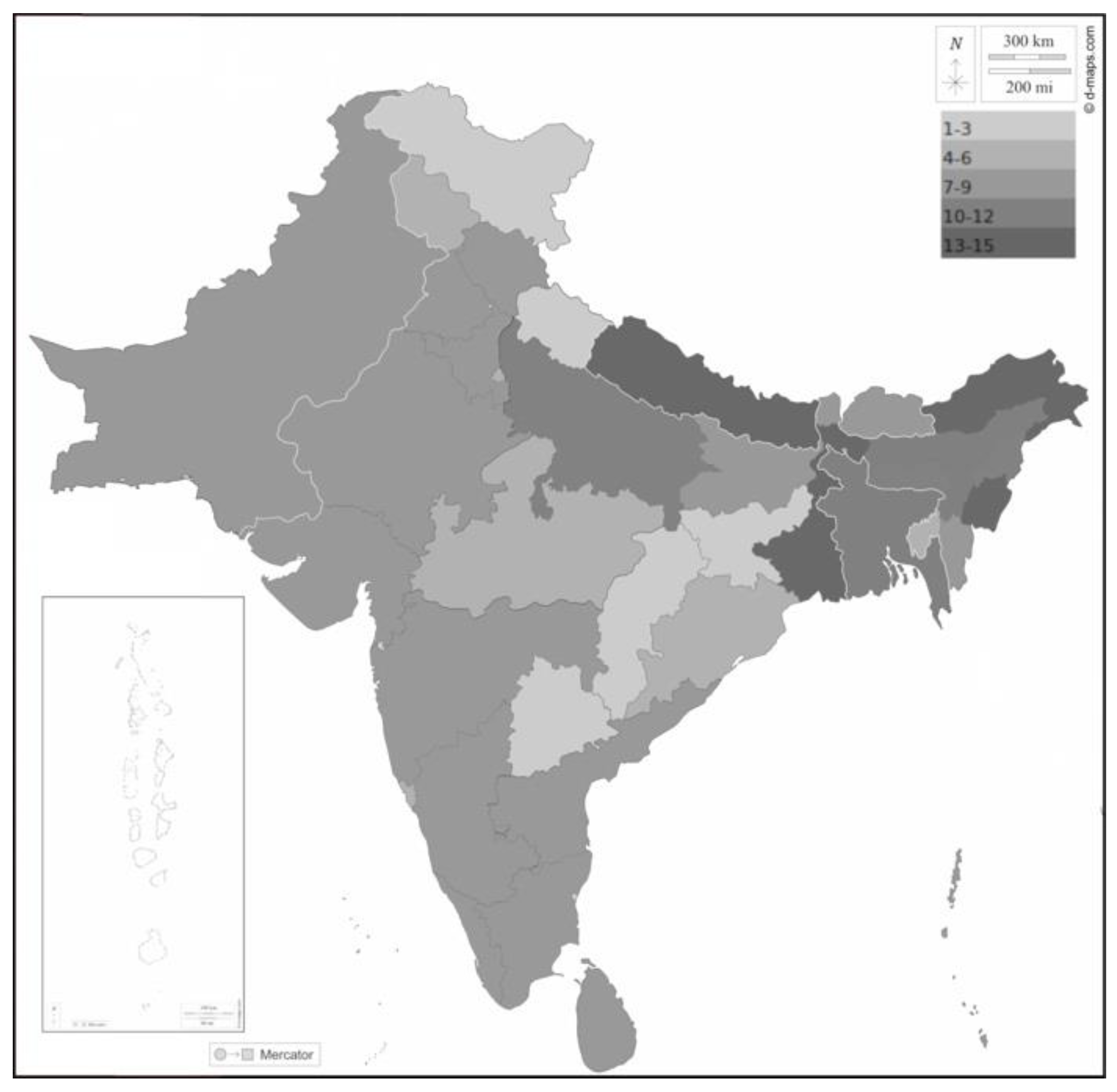

Current knowledge about the distribution of species of the Rattini in the Indian subcontinent is very inconsistent. Most data relate to a few highly adaptable synanthropic species, while most taxa are endemic rodents with a virtually unknown natural history. According to the comprehensive concept of Rattini (as defined by Lecompte et al.) [3], 32 species of 10 genera (Bandicota, Berylmys, Chiropodomys, Dacnomys, Leopoldamys, Micromys, Nesokia, Niviventer, Rattus, Vandeleuria) of rats inhabit the Indian subcontinent [4][5][6][7]. The highest rat diversity occurs in the northeast of the subcontinent (e.g., 15 species in West Bengal, Figure 1), where areas overlap with several species from Southeast Asia (including the A. cantonensis). This is followed by Sri Lanka, the Western Ghats, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (8–9 species each); the diversity there is due to a high degree of local endemism [4]. Although many A. cantonensis records are known from the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka, the involvement of endemic species in the life cycle of this parasite has never been studied.

Figure 1. Diversity of rat species (Rattini) on the Indian subcontinent. The grayscale corresponds to the number of rat species described from each country or state, as indicated in the figure. Borders between countries white; coast, borders between Indian states, and outline of the subcontinent black. The map background was downloaded from https://d-maps.com, accessed on 8 November 2022.

Six species of rats inhabiting the Indian subcontinent were confirmed as A. cantonensis definitive hosts. Three species (Bandicota indica, R. rattus, R. norvegicus) are reported as hosts in studies directly from the subcontinent (Table 1) [8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15], while three others (Berylmys bowersi, Niviventer fulvescens, Rattus exulans) are known hosts in different parts of their distribution range [16]. From an ecological perspective, four of these species (B. indica (Bechstein, 1800), R. rattus, R. norvegicus, R. exulans) are synanthropic pests that frequently encounter humans [7]. The other species B. bowersi (Anderson, 1879), and N. fulvescens (Gray, 1847) [16], avoid human settlements. From the proven definitive hosts, R. rattus probably represents a major source of A. cantonensis infections and should be investigated; R. exulans is of minor importance due to its limited range in the subcontinent; R. norvegicus is typically found in large urban areas and seems unlikely to spread infection in rural areas [4]. On the other hand, data are lacking for several other synanthropic species. A total of 437 Bandicota bengalensis (Gray & Hardwicke, 1833) were examined by Alicata, Renapurkar et al. [10][12], and Limaye et al. [13], with no single A. cantonensis record. According to Agrawal (2000), this species displaces R. norvegicus in large urban areas, especially in Kolkata. If there is a difference in host competence between B. bengalensis and R. norvegicus, this could be the theoretical reason why only one human case is known from Kolkata, compared to Mumbai or Delhi. Rattus tanezumi (Temminck, 1845) has only recently been separated from R. rattus [17][18], so in the case of R. rattus records, it cannot be clearly determined which species was examined. From a geographic perspective, A. cantonensis in rats was never surveyed in most of the subcontinent. The most conspicuous areas for further study are in the northeast of the subcontinent and associated islands (e.g., Andaman and Nicobar Islands, R. rattus was introduced in the Maldives [19]. (Figure 1). In general, the gaps in knowledge about the definitive hosts of A. cantonensis in the Indian subcontinent are compelling, considering that A. cantonensis is easily diagnosed and mainly associated with rats.

Table 1. List of records of A. cantonensis from hosts other than humans, as published from the Indian Subcontinent.

| Country | State | Bandicota indica (Rodentia: Muridae) |

Rattus norvegicus (Rodentia: Muridae) |

Laevicaulis alte (Gastropoda: Veronicellidae) |

Macrochlamys indica (Gastropoda: Ariophantidae) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | Kerala | + | [11] | |||

| India | Maharashtra | + | + | + | [13][14] | |

| India | Tamil nandu | + | [9][12] | |||

| Sri Lanka | Ceylon | + | + | [9][12] |

“+”—Definitive and intermediate hosts were investigated in the Indian subcontinent by region.

2. Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Intermediate Hosts

Like most other metastrongylids, the life cycle of A. cantonensis invariably involves mollusks as obligate intermediate hosts. However, the nematode can develop in a wide range of gastropods, with extreme variation in prevalence among different populations [9][20][21]. Environmental factors, rat density, and the ecology of specific snail or slug species are likely responsible for the observed differences [1][20][22]. Importantly, A. cantonensis exploits both aquatic and terrestrial mollusks, which is one of the reasons for the differences in the local epidemiology of human infections [23][24]. As for gastropods in the Indian subcontinent, Tripathy and Mukhopadhyay (2015) provided a list of the freshwater mollusks of India [25], and Sen et al. summarized the diversity of terrestrial snails in India [26]. Their conclusion that there are 1129 species of terrestrial snails in India alone shows how difficult it is to grasp an enormous diversity of these invertebrates in the Indomalayan region. In addition, there are several smaller studies that list gastropods from different geographic or ecological parts of the subcontinent, such as mangrove mollusks from India [27] or terrestrial snails from Sri Lanka [28]. Many others also attempt to characterize diversity without providing indicative lists [29][30]. Given the low host specificity so far known in A. cantonensis, it is easy to imagine that virtually any of these species could play the role of an A. cantonensis intermediate host.

In most studies, invasive snail species are considered more important than native fauna due to their ecology and high population density. The spread of Lissachatina fulica, one of the most detrimental invasive mollusk species, is commonly referred to as the gateway for the global spread of A. cantonensis [31][32]. Bradybaena similaris (A. Férussac, 1822), Cornu aspersum (O. F. Müller, 1774), Parmarion martensi (Simroth, 1893), Pila spp., Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck, 1822), and P. maculata are associated with A. cantonensis in Southeast Asian countries, Australia, and the Caribbean islands [1][33][34][35][36][37][38][39]. Barrat et al. [1] provide a detailed overview of the prevalence and intensity of infection in species where they are known.

L. fulica and P. canaliculata are described as invasive in the Indian subcontinent [40][41][42], along with Laevicaulis alte (Férussac, 1822), Physa acuta (Draparnaud, 1805), and several other species [42][43][44][45][46][47]. L. fulica is common in almost all states, locally at densities, with negative impacts on agriculture [48]. P. canaliculata has invaded various water bodies in the Indian subcontinent [40], L. alte is widely reported in India and is known to have negative impacts on native snail species in the area [49]. Although there is no comprehensive study summarizing mollusk invasion across the subcontinent, the online data (www.iNaturalist.org, accessed on 8 November 2022) show a wide occurrence of the major invasive snails and slugs in India.

To date, few studies have addressed A. cantonensis in mollusks in the Indian subcontinent. Limaye et al. reported A. cantonensis infection in Macrochlamys indica (Godwin-Austen, 1883) [13]; the other few studies in the subcontinent [10][14][50][51] focused on a single species, the invasive slug L. alte [50].

3. Snail Consumption

Limited information is available on the scale of edible snail consumption in the Indian subcontinent. Snail consumption is well-known in some parts of India, such as the northeastern region, West Bengal, and other places such as Bihar, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu [52][53][54][55]. In these regions, snail meat is well known among urbanites and rural tribal communities for its therapeutic and culinary uses [56]. Although the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) has supported the introduction of snail farming, there are few snail farms in the country. Instead, snails are collected from the wild rather than being cultivated [57]. Freshwater snails, Pila globosa (Swainson, 1822), Bellamya bengalensis (Lamarck, 1822), Viviparus viviparus (Linnaeus, 1758), and several species of terrestrial snails are among the snails reported to be most consumed in many parts of India [56][58][59][60]. Sharma et al. reported a case of angiostrongylosis in humans after consumption of raw slugs L. alte [50] but this species has not been mentioned in studies on the consumption of edible mollusks.

Consumption of raw or insufficiently cooked snails is a common source of human infection in Southeast Asian countries such as China, Taiwan, Thailand, and Hong Kong, including reports of associated clusters of infection [23][61]. However, nematode larvae are sensitive to high temperatures, and even short boiling kills L3 of A. cantonensis in infected mollusks [62]. Snails used in reviewed traditional Indian dishes are always prepared by boiling or frying for 5–10 min with various flavors and spices. Technically, following these procedures prevents the presence of live infectious larvae in cooked dishes. Importantly, many recipes recommend soaking the snails in water for 24 h before use. Together with the initial cleaning, this is a critical moment that deserves attention from an epidemiological point of view. The L3 actively escape from snails [63] and can contaminate cooking surfaces and utensils in high numbers [64]. Reportedly, the water from the soaked snails is used as eye drops to treat conjunctivitis as a traditional remedy [65], which may pose an additional risk of angiostrongylosis since larvae may enter the digestive system through the nasolacrimal duct.

References

- Barratt, J.; Chan, D.; Sandaradura, I.; Malik, R.; Spielman, D.; Lee, R.; Marriott, D.; Harkness, J.; Ellis, J.; Stark, D. Angiostrongylus cantonensis: A review of its distribution, molecular biology and clinical significance as a human pathogen. Parasitology 2016, 143, 1087–1118.

- York, E.M.; Creecy, J.P.; Lord, W.D.; Caire, W. Geographic range expansion for rat lungworm in North America. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1234–1236.

- Lecompte, E.; Aplin, K.; Denys, C.; Catzeflis, F.; Chades, M.; Chevret, P. Phylogeny and biogeography of African Murinae based on mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequences, with a new tribal classification of the subfamily. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008, 8, 199.

- Agrawal, V.C. Taxonomic Studies on Indian Muridae and Hystricidae (Mammalia: Rodentia); Rec. zool. Surv. India, Occasional Paper No. 180. i-viii; Director, Zoological Survey of India: Calcutta, India, 2000; pp. 1–186.

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed.; JHU Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-8018-8221-4.

- Prakash, I.; Singh, P.; Nameer, P.; Ramesh, D.; Molur, S. South asian muroids. Mamm. S. Asia 2015, 2, 574–642.

- Wilson, D.E.; Lacher, T.E.; Mittermeier, R.A. Handbook of the Mammals of the World; Rodents II; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; Volume 7.

- Parmeter, S.N.; Chowdhury, A.B. Angiostrongylus cantonensis in India. Bull. Calcutta Sch. Trop. Med. 1966, 14, 38.

- Alicata, J.E. Biology and distribution of the Rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, and its relationship to eosinophilic meningoencephalitis and other neurological disorders of man and animals. Adv. Parasitol. 1965, 3, 223–248.

- Renapurkar, D.M.; Bhopale, M.K.; Limaye, L.S.; Sharma, K.D. Prevalence of Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection in commensal rats in Bombay. J. Helminthol. 1982, 56, 345–349.

- Thomas, M.; Thangavel, M.; Thomas, R.P. Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Nematoda, Metastrongylidae) in bandicoot rats in Kerala, South India. Infect. Dis. 2015, 8, 324–326.

- Alicata, J.E. The presence of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in islands of the Indian ocean and probable role of the giant African snail, achatina fulica, in dispersal of the parasite to the pacific islands. Can. J. Zool. 1966, 44, 1041–1049.

- Limaye, L.S.; Pradhan, V.R.; Bhopale, M.K.; Renapurkar, D.M.; Sharma, K.D. Angiostrongylus cantonensis study of intermediate paratenic and definitive hosts in greater Bombay India. Helminthologia 1988, 25, 31–35.

- Limaye, L.S.; Bhopale, M.K.; Renapurkar, D.M.; Sharma, K.D. The distribution of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen) in the central nervous system of laboratory rats. Folia Parasitol. 1983, 30, 281–284.

- Dissanaike, A.S. The Proper Study of Mankind; Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1968; pp. 115–142.

- Yong, H.S.; Eamsobhana, P. Definitive rodent hosts of the rat lungworm Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2013, 29, 111–115.

- Adhikari, P.; Han, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-K.; Kim, T.-W.; Thapa, T.B.; Subedi, N.; Kunwar, A.; Banjade, M.; Oh, H.-S. New record of the Oriental house rat, Rattus tanezumi, in Nepal inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome B gene sequences. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2018, 3, 386–390.

- Aplin, K.P.; Brown, P.R.; Jacob, J.; Krebs, C.J.; Singleton, G.R. Field Methods for Rodent Studies in Asia and the Indo-Pacific; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Melbourne Australia, 2003; ISBN 1863203931.

- Bentley, E.; Bathard, A. The rats of Addu Atoll, Maldive Islands. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1959, 2, 365–368.

- Kim, J.R.; Hayes, K.A.; Yeung, N.W.; Cowie, R.H. Diverse gastropod hosts of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the rat lungworm, globally and with a focus on the Hawaiian Islands. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94969.

- Cowie, R.H. Biology, systematics, life cycle, and distribution of Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the cause of rat lungworm disease. Hawaii J. Med. Public Health 2013, 72, 6.

- Kliks, M.M.; Palumbo, N.E. Eosinophilic meningitis beyond the Pacific Basin: The global dispersal of a peridomestic zoonosis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the nematode lungworm of rats. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 34, 199–212.

- Lv, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.-X.; Hu, L.; Yang, K.; Steinmann, P.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.-Y.; Utzinger, J.; Zhou, X.-N. Invasive snails and an emerging infectious disease: Results from the first national survey on Angiostrongylus cantonensis in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e368.

- Richards, C.S.; Merritt, J.W. Studies on Angiostrongylus cantonensis in molluscan intermediate hosts. J. Parasitol. 1967, 53, 382.

- Tripathy, B.; Mukhopadhayay, A. Freshwater molluscs of India: An insight of into their diversity, distribution and conservation. In Aquatic Ecosystem: Biodiversity, Ecology and Conservation; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 163–195.

- Sen, S.; Ravikanth, G.; Aravind, N. Land snails (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of India: Status, threats and conservation strategies. J. Threat. Taxa 2012, 4, 3029–3037.

- Boominathan, M.; Ravikumar, G.; Chandran, M.D.S.; Ramachandra, T.V. Mangrove associated molluscs of India. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Conservation and Management of Wetland Ecosystems, Kerala, India, 6–9 November 2012; Volume 7, pp. 1–11.

- Ratnapala, R. Land snails: Distribution and notes on ecology. In Ecology and Biogeography in Sri Lanka; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 391–411.

- Strong, E.E.; Gargominy, O.; Ponder, W.; Bouchet, P. Global diversity of gastropods (Gastropoda; Mollusca) in freshwater. Freshw. Anim. Divers. Assess. 2008, 198, 149–166.

- Mavinkurve, R.G.; Shanbhag, S.P.; Madhyastha, N. Non-marine molluscs of Western Ghats: A status review. Zoos’ Print J. 2004, 19, 1708–1711.

- Thiengo, S.; Maldonado, A.; Mota, E.; Torres, E.; Caldeira, R.; Carvalho, O.; Oliveira, A.; Simões, R.; Fernandez, M.; Lanfredi, R. The giant African snail Achatina fulica as natural intermediate host of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Pernambuco, northeast Brazil. Acta Trop. 2010, 115, 194–199.

- Wang, Q.-P.; Chen, X.-G.; Lun, Z.-R. Invasive fresh water snail, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 1119–1120.

- Cowie, R.H. Angiostrongylus cantonensis: Agent of a sometimes fatal globally emerging infectious disease (rat lungworm disease). ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 2102–2104.

- Eamsobhana, P.; Yong, H.S.; Prasartvit, A.; Wanachiwanawin, D.; Boonyong, S. Geographical distribution and incidence of Angiostrongylus lungworms (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) and their rodent hosts in Thailand. Trop. Biomed. 2016, 33, 35–44.

- Hamilton, L.J.; Tagami, Y.; Kaluna, L.; Jacob, J.; Jarvi, S.I.; Follett, P. Demographics of the semi-slug Parmarion martensi, an intermediate host for Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Hawai‘i, during laboratory rearing. Parasitology 2021, 148, 153–158.

- Kim, J.R.; Wong, T.M.; Curry, P.A.; Yeung, N.W.; Hayes, K.A.; Cowie, R.H. Modelling the distribution in Hawaii of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (rat lungworm) in its gastropod hosts. Parasitology 2019, 146, 42–49.

- Tesana, S.; Srisawangwong, T.; Sithithaworn, P.; Laha, T.; Andrews, R. Prevalence and intensity of infection with third stage larvae of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in mollusks from Northeast Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 80, 983–987.

- Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Yao, J.; Yang, M.; Guo, Y.; Deng, Z.; Mao, Q.; Li, S.; Duan, L. Comparative proteomics suggests the mode of action of a novel molluscicide against the invasive apple snail Pomacea canaliculata, intermediate host of Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2022, 247, 111431.

- Yang, T.-B.; Wu, Z.-D.; Lun, Z.-R. The apple snail Pomacea canaliculata, a novel vector of the rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis: Its introduction, spread, and control in China. Hawaii J. Med. Public Health 2013, 72, 23.

- Baloch, W.A.; Memon, U.N.; Burdi, G.H.; Soomro, A.N.; Tunio, G.R.; Khatian, A.A. Invasion of channelled apple snail Pomacea canaliculata, Lamarck (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae) in Haleji Lake, Pakistan. Sindh Univ. Res. J. SURJ (Sci. Ser.) 2012, 44, 263–266.

- Joshi, R.C. Problems with the management of the golden apple snail Pomacea canaliculata: An important exotic pest of rice in Asia. In Proceedings of the Area-Wide Control of Insect Pests: From Research to Field Implementation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 257–264.

- Rekha Sarma, R.; Munsi, M.; Neelavara Ananthram, A. Effect of climate change on invasion risk of giant African snail (Achatina fulica Férussac, 1821: Achatinidae) in India. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143724.

- Saha, C.; Pramanik, S.; Chakraborty, J.; Parveen, S.; Aditya, G. Abundance and body size of the invasive snail Physa acuta occurring in Burdwan, West Bengal, India. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2016, 4, 490–497.

- Saha, C.; Parveen, S.; Chakraborty, J.; Pramanik, S.; Aditya, G. Life table estimates of the invasive snail Physa acuta Draparnaud, 1805, occurring in India. Ekologia 2017, 36, 60–68.

- Paul, P.; Aditya, G. Invasion of the freshwater snail Physella acuta (Draparnaud, 1805) in selected ponds of North Dinajpur, India. J. Environ. Biol. 2021, 42, 577–581.

- Raut, S.K.; Mandal, R.N. Natural history of the garden slug Laevicaulis alte. J. Bengal Nat. Hist. Soc. 1984, 3, 104–105.

- Thakuri, B.; Acharya, B.K.; Sharma, G. Population density and damage of invasive giant African snail Achatina fulica in organic farm in east Sikkim, India. Indian J. Ecol. 2019, 46, 631–635.

- Sridhar, V.; Vinesh, L.S.; Jayashankar, M. Mapping the potential distribution of Achatina fulica (Bowdich) (Stylommatophora: Achatinidae) in India using CLIMEX, a bioclimatic software. Pest Manag. Hortic. Ecosyst. 2014, 20, 14–21.

- Husain, A.; Husain, H.J.; Hasan, W.; Kendra, J.K.V. New records of tropical leather-leaf slug Laevicaulis alte (Ferussac, 1822) from Dehra Dun (Uttarakhand) and Jamshedpur (Jharkhand), India. Int. J. Agric. Appl. Sci. 2021, 2, 145–150.

- Sharma, K.D.; Renapurkar, D.M.; Bhopale, M.K.; Nathan, J.; Boraskar, A.; Chotani, S. Study of a focus of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Greater Bombay. Bull Haffkine 1981, 9, 38–46.

- Mahajan, R.; Almeida, A.; Sengupta, S.; Renapurkar, D. Seasonal intensity of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in the intermediate host, Laevicaulis alte. Int. J. Parasitol. 1992, 22, 669–671.

- Baghele, M.; Mishra, S.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B.; Jung, C.; Ghosh, S. Utilization of snails as food and therapeutic agents by Baiga tribals of Baihar tehsil of Balaghat District, Madhya Pradesh, India. Int. J. Indust. Entomol. 2021, 43, 78–84.

- Dhiman, V.; Pant, D. Human health and snails. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2021, 42, 211–235.

- Prabhakar, A.K.; Roy, S. Ethno-medicinal uses of some shell fishes by people of Kosi river basin of North-Bihar, India. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2009, 3, 1–4.

- Sarkar, T.; Debnath, S.; Das, B.K.; Das, M. Edible fresh water molluscs diversity in the different water bodies of Gangarampur Block, Dakshin Dinajpur, West Bengal. Eco. Env. Cons. 2021, 27, S293–S296.

- Baby, R.L.; Hasan, I.; Kabir, K.A.; Naser, M.N. Nutrient analysis of some commercially important molluscs of Bangladesh. J. Sci. Res. 2010, 2, 390–396.

- Rabha, H.P.; Mazumdar, M.; Baruah, U.K. Indigenous technical knowledge on ethnic dishes of snail in Goalpara district of India. Sch. Acad. J. Biosci. 2014, 2, 307–317.

- Borkakati, R.N.; Gogoi, R.; Borah, B.K. Snail: From present perspective to the history of Assam. Asian Agrihist. 2009, 13, 227–234.

- Ghosh, S.; Jung, C.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B. Snail farming: An Indian perspective of a potential tool for food security. Ann. Aquac. Res. 2016, 3, 1024.

- Bagde, N.; Jain, S. Study of traditional man-animal relationship in Chhindwara district of Madhya Pradesh, India. J. Glob. Biosci. 2015, 4, 1456–1463.

- Tsai, H.-C.; Lin, H.-H.; Wann, S.-R.; Liu, Y.-C.; Huang, C.-K.; Lai, P.-H.; Yen, M.-Y.; Kunin, C.M.; Ger, L.-P.; Lee, S.S.-J.; et al. Eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis associated with eating raw snails: Correlation of brain magneticresonance imaging scans with clinical findings. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 68, 281–285.

- Alicata, J.E. Effect of freezing and boiling on the infectivity of third-stage larvae of Angiostrongylus cantonensis present in and snails and freshwater prawns. J. Parasitol. 1967, 53, 1064.

- Crook, J.R.; Fulton, S.E.; Supanwong, K. The infectivity of third stage Angiostrongylus cantonensis larvae shed from drowned Achatina fulica snails and the effect of chemical agents on infectivity. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1971, 65, 602–605.

- Howe, K.; Kaluna, L.; Lozano, A.; Fischer, B.T.; Tagami, Y.; McHugh, R.; Jarvi, S. Water transmission potential of Angiostrongylus cantonensis: Larval viability and effectiveness of rainwater catchment sediment filters. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209813.

- Prasad, S.; Kumar, M.U.; Kumari, A. Freshwater shellfish, Pila globosa (Gastropoda) favourable endeavour for rural nutrition. Agric. Lett. 2021, 2, 32–35.

More

Information

Subjects:

Parasitology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

933

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

29 Jun 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No