In 2000, the Institute of Public Administration Australia carried out the “Working Together—Integrated Governance” research project, aimed at promoting understanding of the main shift in public administration through the inclusion of integrated solutions across all sectors and levels of government within the governance framework. Within the framework of the project, the following definition of integrated governance was adopted: “Integrated governance describes the structure of formal and informal relationships in order to solve tasks through a method of cooperation, either between government agencies or between different levels of government (local, state), and the non-governmental sector”

[23]. More specifically, integrated governance refers to the horizontal integration of sectoral policies and the different actors involved, to the vertical integration of different levels of governance, as well as to integration beyond administrative boundaries (city administration—regional/national administration). IPAA

[23] lists the assumed results arising from integrated governance: a holistic governance approach, user-oriented governance, cooperation between different services, wider social contribution, increased public interest and a higher level of trust, increased social capital, association of different departments, programs and policies, etc. Citizens’ trust in public institutions and their convergence is a prerequisite for strengthening mutual cooperation in meeting common goals in terms of achieving a better quality of life in local communities

[24]. According to Jacquier

[25], the emergence of initiatives bringing together a wide range of actors is not due to a whim, but a crisis of traditional government that finds itself incapable of devising adequate responses to the new trends and complexities of modern society, as well as to social fragmentation and economic uncertainty. It is precisely the city administration that plays a crucial role in creating a relationship with the community that is based on trust, because if the agenda is transparent, if there are clear rules that apply to everyone equally and if the leadership as a facilitator is ready and open to dialogue, the chances for establishing the basis for beneficial relationships aimed at achieving sustainable solutions are higher.

3. Overview of the Evolution of the Sustainable Development Concept from the Perspective of the Integrated Approach

The following section is a brief developmental overview of the concept of sustainable development based on international documents with an emphasis on the integrated approach, illustrating how this approach was embedded into the foundations of the concept of sustainable development from the very beginning, indicating interconnectedness and interdependence between the two.

The chronological presentation of international documents starts in 1972, when the UN adopted 26 principles at its first environmental conference in Stockholm, one of which (Principle 13) emphasizes the need to adopt an integrated and coordinated approach to development in development planning for the benefit of the environment (UN Environment Programme 1972). As a direct consequence thereof, the principle of integration found its integral place in the first Environment Action Programme of 1973. The term “sustainable development” was introduced into the development discourse within the 1980 World Conservation Strategy; however, the focus was placed on the natural environment, and the human side of sustainable development was not given as much attention. The concept gained popularity through the report “Our Common Future”, known as the Brundtland Report, in which the principle of integration occupies a crucial place as one of the fundamental institutional challenges. The report emphasizes the need to revise the former development direction that led to environmental destruction and the point when development is no longer sustainable. Peti

[26] states that the use of the term “sustainability” has become omnipresent and meaningless, its content not sufficiently tangible to give a clear direction to program situations and its objectives very general instead of specific. In addition to the anthropocentric character and subjectivity in defining the concept of needs, this leads to another problem of the concept of sustainable development, which is its operationalization, i.e., application in practice

[27]. In response to the identified shortcomings, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 marked an important milestone in the promotion and operationalization of the concept of sustainable development, which began to be introduced into national strategic and development documents

[5]. On this occasion, it was clearly stated that the doctrine of good governance is a prerequisite for achieving sustainability locally, meaning that it is impossible to achieve it without the involvement of the local communities and their increased political engagement in the decision-making process

[4]. The basic lesson that emerged from the event is that the concept of sustainable development must begin in the cities as the pillars of this development strategy.

One of the key documents derived from UNCED is the Agenda for Sustainable Development in the 21st Century (Agenda 21 1992), which represents an incentive for further development and implementation of the concept of sustainable development through the request for integration of environmental issues in the creation of sectoral policies. Program for sustainable cities began to emerge in the early 1990s due to activism at the local and national levels around the world, as well as the action of the European Community, the World Bank and UN agencies

[1]. The importance of local administration in the implementation of sustainable development guidelines is acknowledged in Agenda 21 (Chapter 28, point 28.3), which stresses that local administration must work on building and establishing a dialogue with its citizens, local organizations and the private sector, so that, through frequent consultations and achieving consensus, it is able to adopt their useful knowledge and information. Local Agenda 21 (1996) empowers local administrations to implement the principles of Agenda 21 locally, and promoting the participation of all social actors, especially socially marginalized groups, is declared as a fundamental element. At the same time, another important document at the European level, the Charter of European Cities and Towns Towards Sustainability, the so-called Aalborg Charter (1994), emphasizes the key role of cities and their responsibility in achieving sustainable local communities. Accordingly, European cities are joining the European Sustainable Cities & Towns Campaign launched to achieve the objectives set out in the Local Agenda 21. The human face of sustainable development has gained importance through the Habitat Agenda (UN Habitat II City Summit, Istanbul, 1996), which highlights the importance of environmental and social aspects of sustainable urban development in raising the quality of life of citizens. Wheeler

[1] states that these documents result in goals important for urban sustainability: the preservation of open spaces and vulnerable ecosystems, reduced use of cars, a reduction in waste and pollution, decent and affordable housing, improved social equality and opportunities for marginalized and socially disadvantaged citizens, strengthening the local economy, etc. In the same period, the popularization of the concept of sustainable development influenced European development policies, wherein a sustainable approach was set as the fundamental idea

[26]. The principle of sustainable development has received strong support within the EU policy framework, which has followed UN-led global initiatives. Article 6 of the Amsterdam Treaty (1997) clearly links the concept of sustainable development to integration as one of the fundamental principles. Lafferty conceptualized sustainability as a question of “policy integration”, which speaks in support of the aforementioned claim that the concepts of sustainability, good governance and participation are intertwined and interdependent

[5].

The emerging concept of solving urban issues through the integrated approach occupied an important place at the Vienna Forum, which was held in 1998, and the reason for its maintenance is the Commission’s Action Plan for Sustainable Urban Development, adopted in the same year. Among the basic principles of the Action Plan is a holistic and integrated approach to urban issues, as well as a partnership aimed at achieving a sense of ownership of all actors. The Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (Aarhus Convention 1998) highlights the involvement of all social actors in the decision-making process, the right to access information and access to justice in environmental protection issues

[28]. Bush et al.

[29] state that this is a new type of agreement that clearly links the environment and human rights in order to underline the right to participation of all actors who, in interaction with public authorities, can offer the knowledge required to address environmental issues crucial to achieve sustainable development and strengthen the participatory process. At the Gothenburg Summit in 2001, the EU leaders, based on a proposal from the European Commission, presented the EU’s first sustainable development strategy which stresses the interconnectedness of environmental, social and economic impacts on development. At the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) held in Johannesburg in 2002, the principle of sustainable development received strong political support.

The revised EU Sustainable Development Strategy of 2006 highlighted the need for a gradual change in the unsustainable system of production and consumption, as well as the introduction of an integrated approach in the process of drafting EU guidelines and policies, with particular emphasis on the principles of solidarity and partnership. The EU underlined the need for an integrated and holistic approach to tackling urban issues by adopting a series of formal documents on urban development policies. The Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities was signed in 2007 by European ministers at an Informal Ministerial Meeting on Urban Development and Territorial Cohesion

[30]. Its importance lies in the fact that its basic objective is to improve urban governance based on the integrated approach defined as a process in which spatial, sectoral and temporal aspects of key urban policy areas are coordinated with the emphatic participation of all social actors.

In 2008 in Marseille, ministers advocated the implementation of the Leipzig Charter and agreed on holistic urban development strategies that highlight the need to improve sectoral policy coordination and focus on knowledge and interdisciplinary skills required for developing these policies. The Charter emphasizes how positive contributions of integrated urban development policy are manifested through reconciliation and harmonization of interests of different levels of government and actors (state, region, city, citizens, economic operators, etc.) and better utilization, efficiency and cost-effectiveness of public-private initiatives and investments. Furthermore, it states that integrated urban development has a positive impact on governance structures, thereby improving or strengthening the competitiveness of cities and promoting coordination of infrastructure development. The Charter also stresses the need to improve neglected neighborhoods, focusing on the dimension of social housing and social housing policy (strengthening social cohesion and stability) and draws attention to the following relevant policies: improving the spatial environment (energy efficiency), strengthening the local economy (local labor market policy, stability), proactive education policy (especially for younger generations) and efficient and accessible public transport (mobility, accessibility, reduced environmental pollution). Moreover, it acknowledges the need for a practical tool to put into practice the general objectives and recommendations of the Leipzig Charter. To this end, the Reference Framework for Sustainable Cities (RFSC) has been developed, a web-based tool launched by the European Commission to encourage European cities to cooperate and apply the integrated approach in urban development planning, and to evaluate their own strategies, programs and projects, compare them with other cities and thus exchange experiences and improve their knowledge and skills.

Furthermore, in 2008, the European Commission launched the Covenant of Mayors initiative, which aims to connect energy-conscious European cities into a network, fostering a continuous exchange of experiences. With the adoption of the related Agreement, the mayors committed to drafting a Sustainable Energy Action Plan (SEAP) within two years (in 2015, the Covenant of Mayors turned Sustainable Energy Action Plans (SEAPs) into Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plans (SECAPs)). SEAP is a fundamental document that identifies the actual state, based on the collected data on the existing situation, and provides precise and clear determinants for the implementation of projects, the application of energy efficiency measures and the use of renewable energy sources and environmentally friendly fuels at the city level, which will result in a reduction in CO2 emissions by more than 20% by 2020, or by 40% by 2030.

In the Cities of Tomorrow report (Cities of Tomorrow—Challenges, visions, ways forward, 2011), the European Commission presented the European model of urban development and the challenges, visions and projections of the future development of cities responsible for achieving sustainable development of the EU. Emphasizing that the European model of sustainable urban development is at risk (demographic changes, lack of continuous economic development and job creation, increased levels of unemployment and poverty, rise of social and spatial segregation, etc.), the report proposes possibilities of transforming threats into positive challenges through the adoption of new forms of governance, namely, a holistic model of sustainable urban development.

The Rio + 20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, held in Rio de Janeiro in 2012, resulted in the adoption of a document entitled The Future We Want, which indicates the importance of participation of all actors in decision making, planning and implementation of policies and programs for sustainable development at all levels.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development of 2015 sets out seventeen Sustainable Development Goals calling for action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure peace and prosperity. The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (2015), where the Agenda 2030 was adopted, was almost entirely unnoticed in Croatia. Neither the media, the appropriate state administrative organizations or the office of the then-president, who led the Croatian delegation at the meeting, adequately informed the Croatian public about the process of final consideration and agreement, which resulted in the adoption of the new seventeen SDGs

[31]. The defined Sustainable Development Goals are universal, complementary and represent an era of shared responsibility for humanity in addressing key systemic barriers to sustainable development through a clear framework for shaping transformative recovery

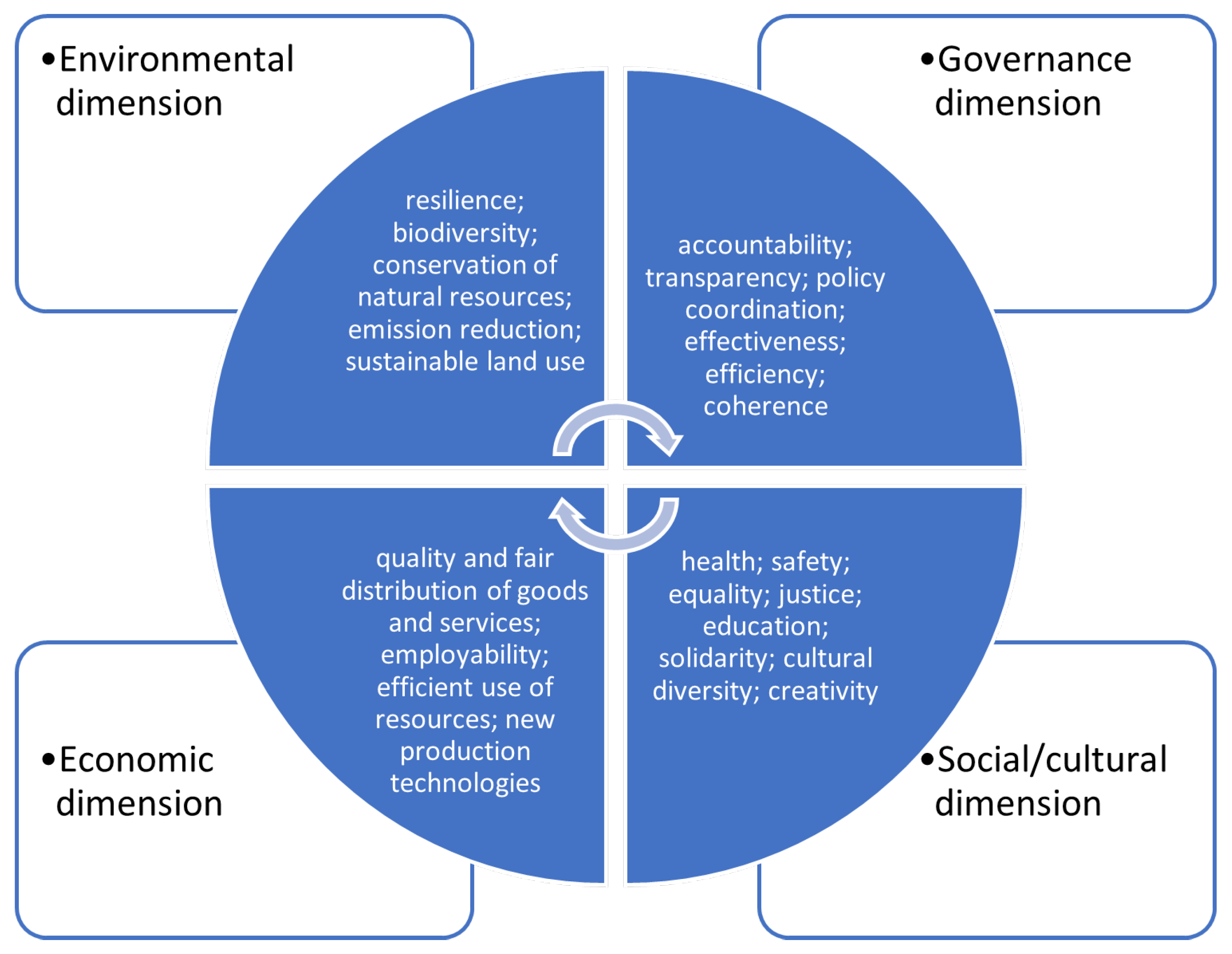

[32]. National authorities, both regional and local, play an equally important role in this process, so it is not surprising that one of the goals is aimed precisely at cities as drivers of development, which must focus all their efforts to achieve inclusiveness, security and resilience that permeate all dimensions of sustainable development (ecological, economic, cultural, management and social). Goal 11 explicitly states that strengthening national and regional development planning should support positive economic, social, and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas. Additionally, cities should implement integrated policies and plans regarding inclusion, resource efficiency, mitigation and adaptation to climate change and resilience to natural disasters. Modern cities define different development missions (smart/resilient/circular/sustainable/green/digital/low-carbon cities) and, despite the differences in focus, their common starting point is meeting the seventeen global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In the same year, a number of relevant events followed: an action plan to limit global warming, the Paris Agreement, was reached, entering into force in 2016, and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 was adopted, as well as the Addis Ababa Action Agenda at the Third International Conference on Financing for Development. Furthermore, the Habitat III United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development held in Quito in October 2016 featured the adoption of the New Urban Agenda

[33]. In accordance with Resolution 66/207 and the two-decade cycle (1976, 1996 and 2016), the General Assembly wanted this conference to raise awareness of the global commitment to sustainable urbanization and set Gold Global Standards for sustainable development

[32]. The New Agenda addressed the challenges of planning and governing cities and villages with a view to fulfilling their core role as drivers of sustainable development and further reflected on how they can implement the new global development goals and the Paris Agreement on climate change. By formulating policies, plans and programs at the local, national, regional and international levels, the New Urban Agenda considers the role of sustainable urbanization as a driver of sustainable integrated development and urban–rural connectivity, as well as the interdependence of social, economic and environmental dimensions of sustainable development in promoting stable, prosperous and inclusive communities

[32]. All governance levels and civil society willing to participate in open, inclusive, multilevel, participatory and transparent monitoring are invited to track the implementation progress of the Agenda. Until that point, Habitat conferences held the status of being the most progressive within the UN system when it comes to civil society engagement. However, civil society representatives were overlooked in Quito, as evidenced by the rejection of two of their proposals; the first for the introduction of a multi-actor panel on sustainable urbanization that would provide an institutional mechanism to promote their ideas and proposals, and the second for the proclamation of the UN International Decade of Sustainable Urbanization, which would raise broader awareness of the topic.

The Urban Agenda for the EU—Pact of Amsterdam

[34] is of great importance for the achievement of the EU’s strategic objectives, and its implementation largely depends on the active involvement and cooperation of urban authorities with the local community, civil society, the private sector and academia in order to improve the legislative framework so as to achieve the objectives at a minimum cost, i.e., more accessible funding through EU funds through simplification and better coordination, the creation of a database on urban issues and the exchange of successful experiences through networked information sharing. It points out that in order to achieve the full potential of urban areas, it is necessary to improve policy complementarity through the involvement of all levels of government, ensuring coordination and effective interaction between different sectors, while respecting the principles of subsidiarity and the competencies of each level. The Urban Agenda stresses how a balanced, sustainable and integrated approach to urban challenges must be in line with the previously mentioned Leipzig Charter on Sustainable Cities, the Territorial Agenda 2020

[35], the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the global Habitat III New Urban Agenda. This approach also implies that achieving good urban governance requires the representation of economic, environmental, social, territorial and cultural aspects of development. The priority themes and issues of common interest of the Urban Agenda are in line with the priorities of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth: inclusion of migrants and refugees, air quality, urban poverty, housing, circular economy, jobs and skills in the local economy, climate adaptation (including green infrastructure solutions), energy transition, sustainable land use and nature-based solutions, urban mobility, digital transition and innovative and responsible public procurement.

Given the lack of a single European urban policy, the presentation of relevant international documents indicates a growing recognition of the role cities play in achieving sustainability in the EU, which is supported by a series of official documents, Acquis Urbain (the Bristol Accord (2005), the Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities (2007), the Marseille Declaration

[36], the Toledo Declaration (2010), the Territorial Agenda (2011), Cities of Tomorrow—Challenges, Visions, Ways Forward (2011), Riga Declaration—Towards an EU Urban Agenda (2015), the Pact of Amsterdam (Urban Agenda, 2016), New Charter, or the revised Leipzig Charter (2020), Ljubljana Agreement (2021), etc.), used for developing a European system aimed at strengthening the integrated approach to urban development. The intention behind the overview of the development of the sustainable development concept in the context of the integrated approach in international documents was to point to their strong interdependence, followed by an expanded and holistic understanding of the concept of sustainable development that considers all its fundamental dimensions equitably, and the last but most important aspect was the exponential advocacy of the necessity of applying the integrated approach to development, fostered by the processes of decentralization and Europeanization that empower European cities to implement the integrated approach.