Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jian Xu | -- | 3896 | 2023-06-07 09:16:27 | | | |

| 2 | Fanny Huang | Meta information modification | 3896 | 2023-06-08 12:30:27 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Kaur, L.; Singh, J.; Zeng, F. Potato Phytochemicals. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45276 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Xu J, Li Y, Kaur L, Singh J, Zeng F. Potato Phytochemicals. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45276. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Xu, Jian, Yang Li, Lovedeep Kaur, Jaspreet Singh, Fankui Zeng. "Potato Phytochemicals" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45276 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Xu, J., Li, Y., Kaur, L., Singh, J., & Zeng, F. (2023, June 07). Potato Phytochemicals. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45276

Xu, Jian, et al. "Potato Phytochemicals." Encyclopedia. Web. 07 June, 2023.

Copy Citation

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) has gradually become a stable food worldwide since it can be a practical nutritional supplement and antioxidant as well as an energy provider for human beings. Financially and nutritionally, the cultivation and utility of potatoes is worthy of attention from the world. Exploring the functionality and maximizing the utilization of its component parts as well as developing new products based on the potato is still an ongoing issue. To maximize the benefits of potato and induce new high-value products while avoiding unfavorable properties of the crop has been a growing trend in food and medical areas.

phytochemicals

nutrition

potato

1. Introduction

The role of potatoes on the table varies with the development of the region. In many developed countries, it acts as a vegetable, with intakes varying from the lowest value in the UK of 102 g to the maximum intake in Belarus of 181 g per capita per day for adults [1]. On the other hand, especially in some rural areas of America and in the highlands of Latin American countries, the daily consumption of potato by adults is as much as 5–6 times the quantities in developed countries [2]. China ranked first in potato production and made up about 24.53% of the world production in 2018, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations database [3]. The potatoes have gained fame as a globally consumed food crop mostly due to its qualities of tremendous yield per unit area [4], affordability [5], and large daily consumption. Potato functions as an antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anti-cancer, and anti-diabetes product in human and animal clinical studies [6]. Compounds existing in potatoes such as starch, protein, fiber, mineral, polyphenols, and carotenoids are thought to have a variety of benefits for human beings [6], although there are significant differences in the nutritional profiles and contributions of different potato cultivars to the human body. For the whole potato tuber, the carotenoid concentration of yellow-fleshed potatoes is higher than that of white- or purple-fleshed potatoes, while the anthocyanin concentration of purple potatoes is higher than that of red- or white-fleshed potatoes. Since polyphenols are mainly concentrated in the peel, colored potatoes generally have higher anthocyanin and carotenoid concentrations than whole white potatoes. The potato’s beneficial properties are attributed to the presence of these nutritional compositions.

However, with the increasing concern about weight and diabetes as well as cancer, potato as a carbohydrate-rich food is generally considered to have a high glycemic index and glycemic load [7][8], which is routinely described is being related to the risk of type 2-diabetes [8][9] and weight gain [10]. Promisingly, some studies support the positive effects of eating potatoes on our overall health [11], even though a small minority of them claim that the consumption does not affect weight control or diabetes [6]. In contrast, some research indicates that the consumption of potatoes has a direct association with an increase in hypertension [12] since potassium supplementation has a potential preventative effect on hypertension and chronic disease [13]. Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, especially coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure as well as renal failure (WHO, 2004). This is the reason for the decline in the consumption of potatoes in the past few decades. To change the negative trend and alleviate grain shortages by eating potatoes in some areas, it is crucial to make clear the functions of nutritionally important components of potato tubers and what factors should be first considered when processing certain potatoes.

2. Functional Phytochemicals in Potato

Potatoes are an excellent source of antioxidants, which include carotenoids, anthocyanin, phenolic compounds, and vitamin C. Nutritionally, these compounds play a role in preventing cancer and heart attacks with their potent antioxidative properties [14]. Carotenoids accumulate in many plants, giving yellow, orange, and red colors. The color of yellow potatoes is ascribed to carotenoids, which show high concentrations in yellow cultivars, while the color may be masked by anthocyanins in red- or purple-fleshed potatoes. Carotenoids contain primarily lutein, zeaxanthin, and violaxanthin, all of which are xanthophylls present in the flesh of potatoes. The composition of tuber carotenoid varies with cultivars; however, violaxanthin and lutein usually are the most abundant proportions.

3. Carotenoids and Health Benefits

The quantity of total carotenoids in vegetables varies among cultivars and ranges from 0.038 (potato) to 17.31 (spinach) [15] mg/100 g FW, whereas in potato, the value ranges from 0.038 to 2.00 mg/100 g FW [16][17][18]. Among all the fresh fruits and vegetables analyzed, certain potatoes have a comparable value (2.00 mg/100 g FW) [15] with other vegetables such as cabbage (0.25 to 0.43 mg/100 g FW) [15], strawberry (0.96 to 3.30 mg/100 g FW) [19], and tomato (1.63 to 8.57 mg/100 g FW) [20][21].

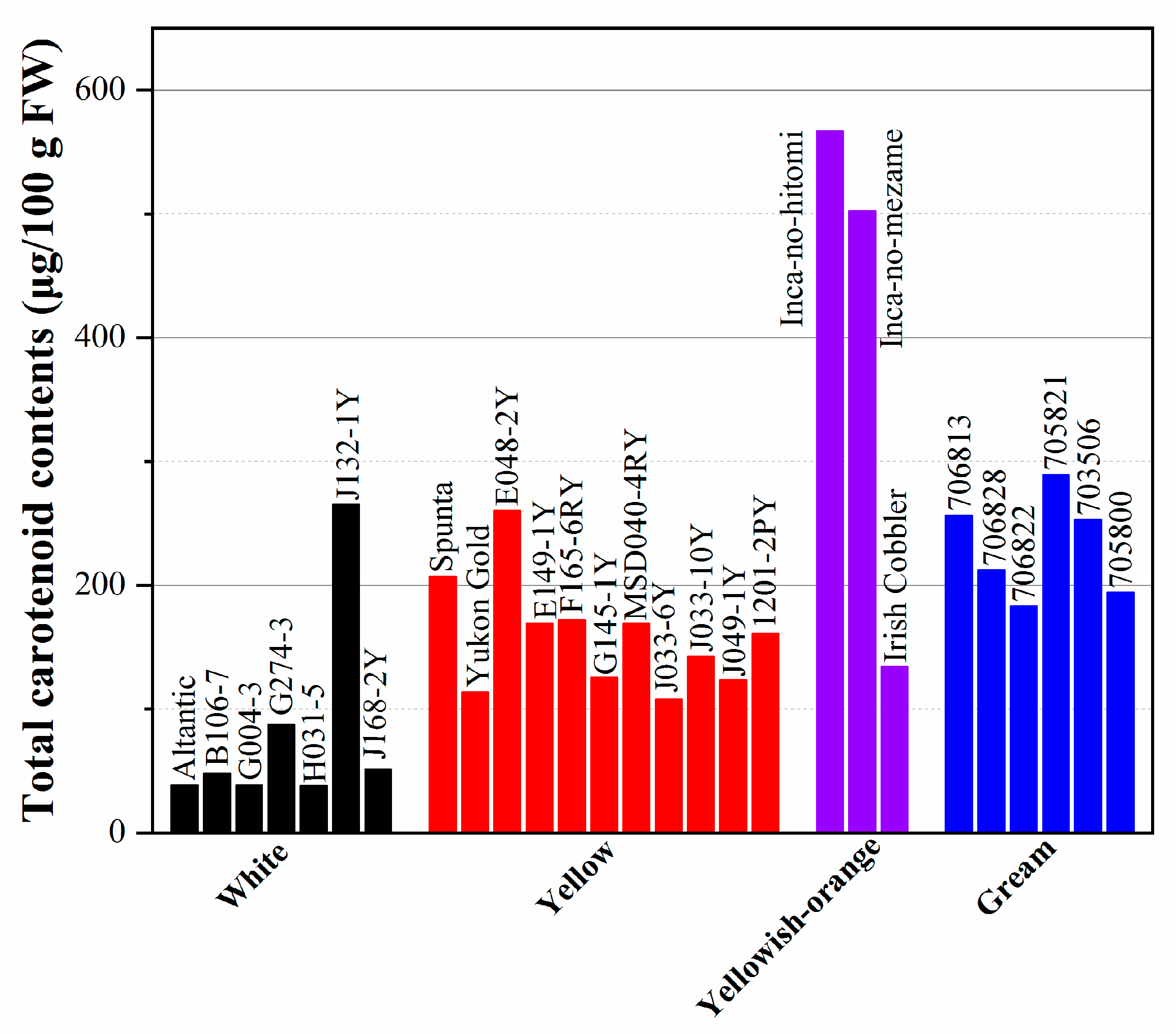

The carotenoid concentration in colored flesh potatoes is shown in Figure 1. The content of carotenoids ranges from 38.1–265 μg/100 g FW in white-fleshed varieties and 107.5–260.3 μg/100g FW in yellow-fleshed cultivars to 567 μg/100g FW in yellowish–orange cultivars; some dark-yellow-fleshed cultivars even have a carotenoid content as high as 2000 μg/100 g FW (as shown in Figure 1). Among all the various colored fresh cultivars, yellow-fleshed varieties have the highest carotenoid content, followed by cream and white. Furthermore, over 100 cultivars grown in Ireland and Spain were shown to have carotenoid content from trace amounts to 28 μg/g DW in the skin and 9 μg/g DW in the flesh [22][23]. The lipophilic extract of potato with total carotenoids ranging from 35 to 795 per 100 g FW flesh shows 4.6–15.3 nmoles of α-tocopherol equivalents per 100 g FW of oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) values [24].

Figure 1. Total carotenoid concentrations by spectrophotometry and HPLC in potatoes.

Furthermore, potato as a staple food is most commonly consumed and has the greatest daily intake every day compared with other selected vegetables. That is to say, potato can be a key and more accessible carotenoid supplement in our daily life. Potato is not the origin of pro-vitamins. However, carotenoids can have provitamin A activity and thus can decrease the risk of several diseases [25][26], age-related macular degeneration, and the onset of cataracts [27][28][29]. The process of carotenoid accumulation is the result of the biosynthesis, degradation, and stable storage of synthetic products [30][31].

Multiple factors control the broad diversity of carotenoid composition and content in storage tissue. Regulation of the catalytic activity of carotenoid biosynthesis can be a key and practical control for the final carotenoid accumulation. Phytoene synthase (PSY) is the rate-limiting step in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway, and manipulation of PSY expression in many plants has been demonstrated to enhance carotenoid synthesis by directing metabolic flux into the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway [32][33][34].

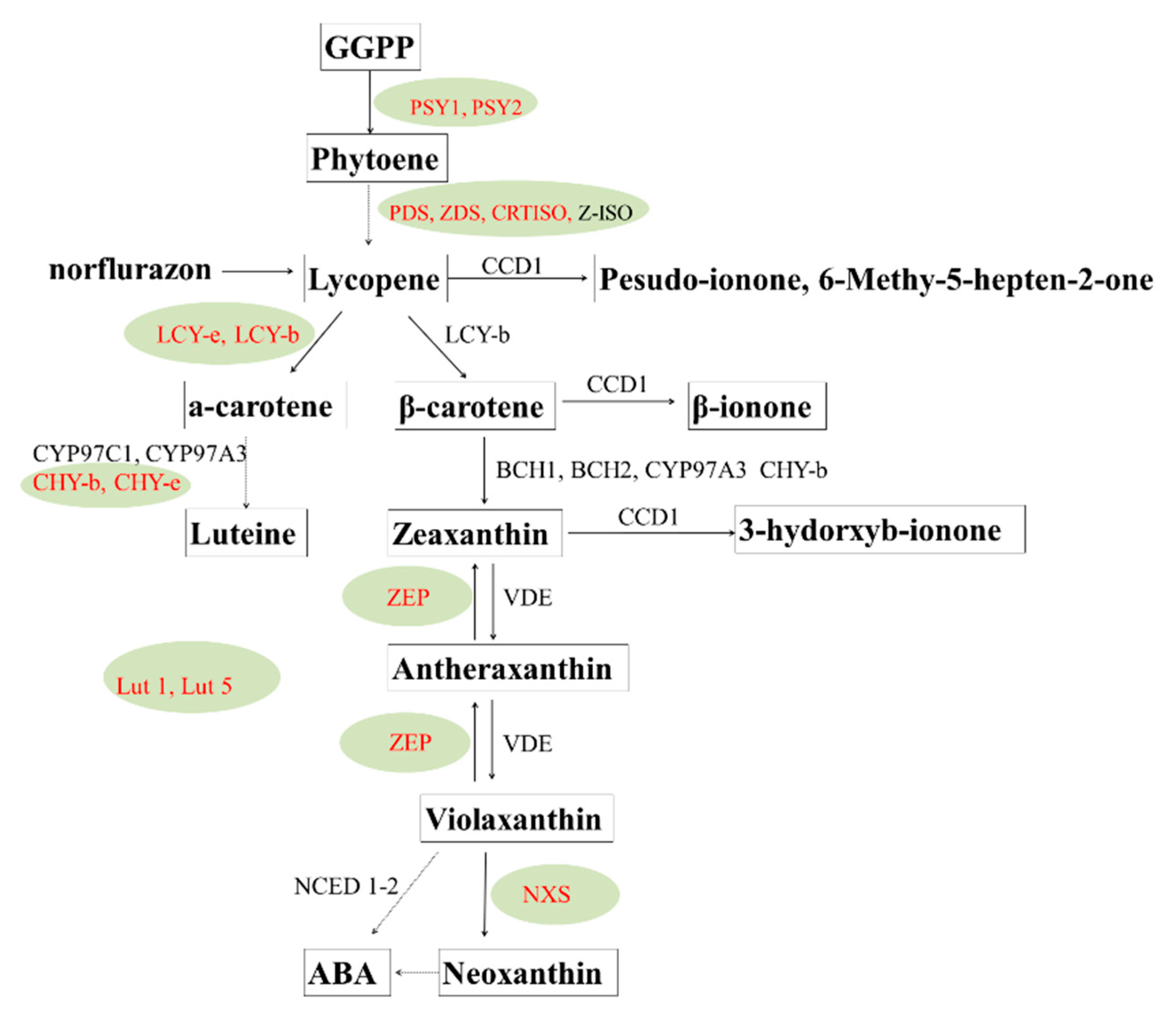

Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCDs) catabolize the enzymatic degradation of carotenoids. Expression of these genes inversely regulates carotenoid accumulation [35][36]. LCY-b and LCY-e can manipulate the synthesis of α-carotene and β-carotene, respectively. The tissue-specific expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes in potato is marked in red color in Figure 2. Methods such as traditional breeding and metabolic engineering approaches have been utilized to improve the tuber carotenoid content. Traditional breeding can increase carotenoids based on broad-sense heritability of carotenoids [37]. The Y locus encodes a β-carotene hydroxylase and largely determines the tuber flesh color and zeaxanthin synthesis [38][39]. Molecular analysis has identified a QTL on chromosome 3 responsible for up to 71% of the carotenoid variation that is probably an allele of β-carotene hydroxylase, and several additional alleles affecting the amount of carotenoid have been identified [40][41]. A variety of transgenic approaches have achieved great success in increasing tuber carotenoids. The overexpression of bacterial phytoene synthase can increase total carotenoids from 5.6 to 35 μg/g DW, luteins 19-fold, and β-carotene from trace amounts to 11 μg/g DW [34]. Furthermore, a study showed that the overexpression of three bacterial genes in the Desiree potato caused a 3600-fold increase in β-carotene to 47 μg/g DW, a 30-fold increase in lutein, and a 20-fold increase in total carotenoids, producing a “golden potato” [42]. Manipulating the vitamin A pathway can fulfill 42% of the daily requirement for vitamin A (retinal activity equivalents) and 34% of the daily requirement for vitamin E by consuming a modest 150 g serving of boiled potatoes [43].

Figure 2. Biosynthesis, metabolic pathway. and gene regulation of carotenoid compounds in potatoes.

4. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activities

Potato supplies considerable phenolic compounds, which are concentrated in the peel and adjoining tissues [44]. The predominant one is chlorogenic acid (CGA), which consists of approximately 80% of the total phenolic acids. Red- and purple-fleshed potatoes usually contain more CGA than white potatoes. CGA may have a potential effect in reducing the risk of type 2-diabetes and slowing the entry of glucose into the bloodstream [45]. CGA in potatoes is synthesized via hydroxycinnamoyl CoA: quinatehydroxycinnamoyltransferase [46][47]. The R2R3 transcription factor StAN1 appears to mediate CGA expression and also regulates anthocyanins [48]. Phenylpropanoid (phenolic acids, flavonols, and anthocyanins) content varies markedly among cultivars, which is related in some way to the genetic diversity [49]. Andean potato landraces show about an 11-fold variation in phenolic acids and flavan-3-ols, and a high correlation between phenolics and total antioxidant activity [50][51][52]. Chilean landraces display 8- or 11-fold more phenylpropanoids than Desiree and Shepody, two common cultivars [53]. The phenolic content extracted from potato peel has been reported to have an antioxidant-mediated protective effect in erythrocytes against oxidative damage. However, polyphenol preservation is one of the keys to the quality of potato, affecting their flavor induction (astringency) and capacity to cause discolorations, such as enzymatic browning reactions [44]. Since most potato phenolics except anthocyanins are colorless, they present in white- and yellow-fleshed cultivars, which are desirable culinary ingredients in many countries. Total phenols/Total phenolic content (TPC) in a variety of plant cultivars as obtained from the Folin–Ciocalteau reagent (FCR) or HPLC was shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Total phenols in a variety of plant cultivars as obtained from the Folin–Ciocalteau reagent (FCR) or HPLC.

| Variety/Plant Cultivar |

FCR | HPLC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| g GAE/kg FW | g GAE/kg DW | mg/100 g FW | mg/100 g DW | |

| Cauliflower | 0.57–2.55 | 5.60–29.13 | 30–217 | |

| Cabbage | 1.70–2.53 | 1.90–26.29 | 0.50 | 125–387 |

| Broccoli | 0.96–3.76 | 1.10–1.14 | 1173 | |

| Spinach | 0.50–2.34 | 11.8 | ||

| Carrot (orange & black) |

0.16–10.29 | 1.10–1.90 | 0.30–39.76 | |

| Brinjal | 0.82–2.92 | |||

| Green bean | 0.78–4.58 | 17.10–66.3 | ||

| Mushroom | 0.09–1.80 | |||

| Tomato | 0.14–2.91 | 26.57 | ||

| Strawberry | 0.99–3.05 | |||

| Blueberry | 2.20–7.53 | |||

| Kiwifruit | 0.80–0.96 | |||

| Pea | 0.80–1.20 | |||

| Brussels sprouts | 147 | |||

| Italian kale | 1127 | |||

| Potato | 0.31–8.83 | 4.48–11.19 | 23.2–67.4 | 260–2852 |

Despite reviewing many research studies, it was difficult to make a comparison between various vegetables since different methods were used previously. By examining the total phenol of plants determined according to the Folin–Ciocalteau (F-C) colorimetric method and expressed on a gram of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per kilogram of fresh weight basis (g GAE/kg FW), potato (0.31 to 8.83 g GAE/kg FW) is found to offer comparable value to certain vegetables and fruits, such as carrot (0.16 to 10.29 g GAE/kg FW) and blueberry (2.20 to 7.53 g GAE/kg FW), and is superior to some cultivars, such as cauliflower (0.57 to 2.55 g GAE/kg FW), cabbage (1.70 to 2.53 g GAE/kg FW) as well as strawberry (0.99 to 3.05 g GAE/kg FW). Furthermore, when expressed on a dry weight basis, potato (4.48 to 11.19 g GAE/kg DW) can provide almost the same quantity of total phenols as spinach. According to the maximum total phenol intake (based on a gram of gallic acid equivalents per kilogram of fresh weight) from plant cultivars, if 200 g potato were consumed every day, the total phenols from that potato would have to be provided by 700 g cabbage or cauliflower, 170 g carrot, 580 g strawberry, or 970 g mushroom; if 200 g potato were consumed every day, the total phenols from that potato ensures would have to be provided by 700 g cabbage or cauliflower, 170 g carrot, 580 g strawberry, or 970 g mushroom. On the other hand, according to the data obtained from the HPLC method, total phenols of potato range from 23.2 to 67.4 mg/100 g FW or 260–2852 mg/100 g DW, which are similar to those in the green bean (17.10 to 66.3 mg/100g FW). According to the data on the Singapore Chinese population aged 45–74 years obtained from the Singapore Chinese Health study from 1993 to 1998, the daily intake of potato is 6.9 g with 4.1 mg GAE/day of TPC. In conclusion, the potato should be a lower-cost alternative than other vegetables and fruits for daily total phenol intake; especially in some development areas, it can be the first consideration as an antioxidant source.

5. Flavonoids and Health Care Functions

Flavonoids in the flesh of white potato contain two leading constituents—catechin and epicatechin—and can be as high as 30 μg/100 g FW, almost twice that in red-and purple-fleshed potatoes [24]. One group suggested that flavonols increased up to 14 mg/100 g FW in fresh-cut tubers and suggested that they can be a valuable dietary source because of the large number of potatoes consumed [54]. The content of flavonols varies by more than 30-fold among different potato genotypes, and there is sizable variation even within the same genotypes. Interestingly, potato flowers can synthesize a 1000-fold higher amount of flavonols than tubers, which contain only micrograms per gram amount of flavonols [47]. Several studies show that quercetin and related flavonols have multiple health-promoting effects, including a reduced risk of heart disease; lower risk of certain respiratory diseases, such as asthma and bronchitis; and a reduced risk of some cancers, including prostate and lung cancer [55].

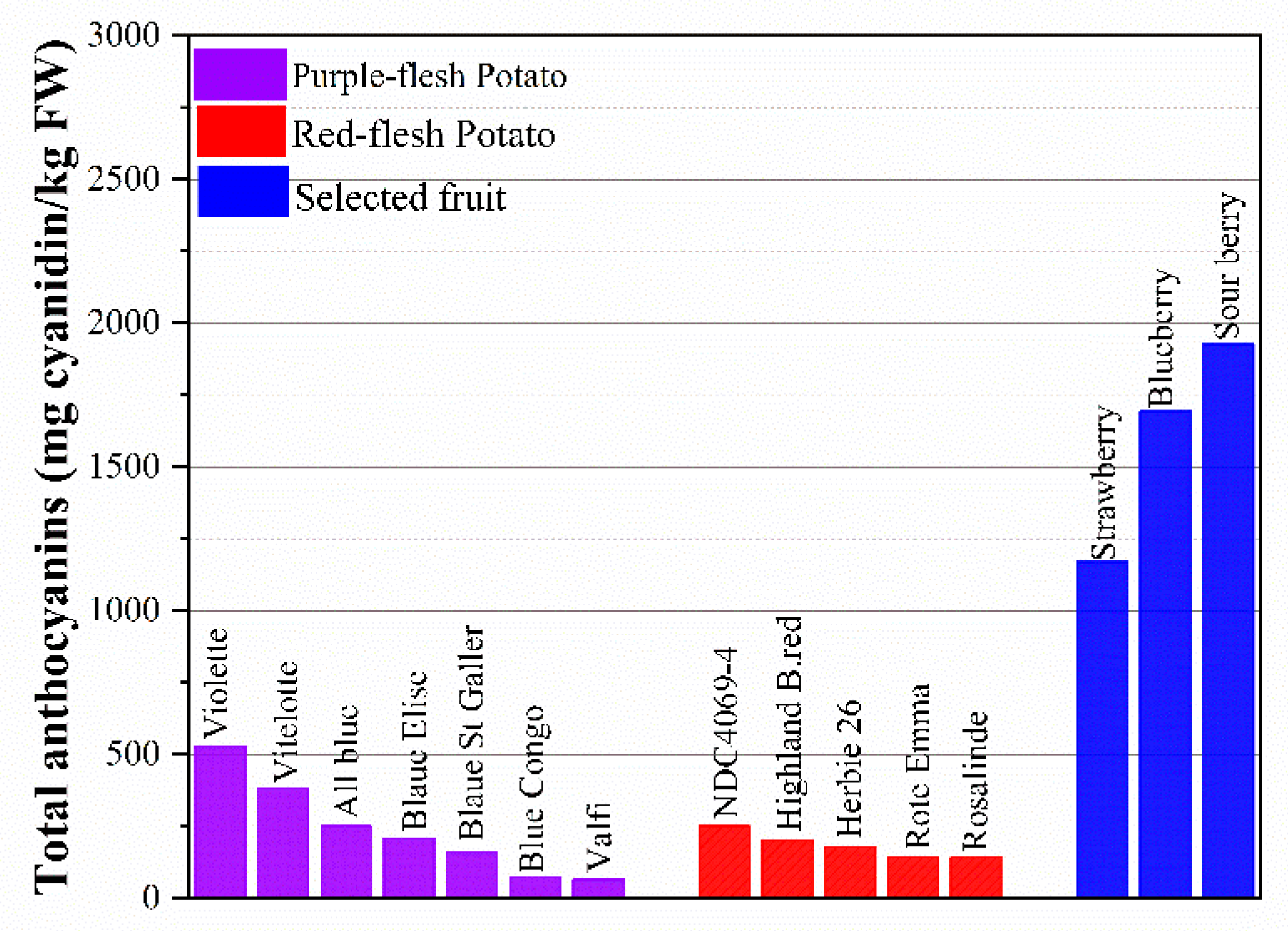

Colored potatoes are rich in anthocyanins that exist abundantly in the skin of the potato or are partially or entirely derived from the flesh. Anthocyanins are natural colorants belonging to the flavonoid family [56]. These compounds are responsible for all the visible colors ranging from the red to blue of fruits, vegetables, flowers, and roots. Anthocyanidins commonly found in plants are delphinidin, cyanidin, petunidin, peonidin, pelargonidin, and malvidin [57]. Anthocyanin-rich foods have been shown to play an important role in the prevention of a wide range of human cancers, such as colon, breast, prostate, oral, and stomach cancers [58], while having no toxic effects on human somatic cells [5]. The total anthocyanin in selected fruits and potatoes is shown in Figure 3. Unpeeled potato with totally pigmented flesh can contain up to 527.4 mg/kg FW of total anthocyanins. Red or purple flesh with skin can be a profitable source of anthocyanins, similar to cranberries, and is superior to red cabbage [59]. As shown in Figure 3, the purple-fleshed potato has a higher total anthocyanin content than red-fleshed cultivars, ranging from 65.5 to 527.4 mg cyanidin/kg FW, while the value is 142–250 mg cyanidin/kg FW in red-fleshed potato. Compared with blueberry (1694 mg cyanidin/kg FW) and strawberry (1171 mg cyanidin/kg FW), which are known as high-anthocyanin foods, some varieties of potatoes are promising and have the potential to meet the demand for anthocyanins in daily life. What is most noteworthy is that potato is a more accessible food and is consumed in greater quantities than strawberry and blueberry since their high cost and seasonality limit the eating of those fruits. Through investigating over 50 colored-fleshed cultivars, researchers have found that anthocyanins vary in the range of 0.5–7 mg/FW in the skin and up to 2 mg/g FW in the flesh [60].

Figure 3. Total anthocyanins (mg cyanidin/kg FW) in selected fruits and potatoes.

An issue that has come to researchers attention is that high-anthocyanin potatoes, usually with colored skin, are not as widely eaten as white or yellow potatoes. Tuber anthocyanin in the periderm is regulated by at least three loci—D, P, and R [61][62][63]. Biochemical and expression analyses revealed that an AN1 transcription factor complex was involved in potato anthocyanin synthesis [64][65], and its global expression in white and purple potatoes was studied using microarray and RNA-seq analysis. Multiple transcription factor variants were identified, including a ten amino acid C-terminal-modified AN1 required for optimal anthocyanin synthesis [66][67][68]. SSR markers for anthocyanin biosynthesis can be a technique for potato breeding programs [69]. Purple-fleshed potatoes known as a high-phenolic cultivar have been proved to benefit health by their anti-cancer properties [70][71][72][73] and amelioration of chromium toxicity [74]. In a mouse model, anthocyanins from purple potatoes were observed to show an effect of attenuating alcohol-induced hepatic injury [75]. In a human feeding study in which adults were fed 150 g of purple potatoes a day for six weeks, results showed that inflammation and DNA damage decreased [76]. Another small human trial suggested people with an average age of 54 years who consumed purple potatoes had a significant drop in blood pressure without any weight gain [77]. In addition, postprandial glycemia and insulinemia were observed to show a downward trend in males fed purple potatoes [77]. A previous study demonstrated that high polyphenol content in potato was inversely associated with their glycemic index [78]. For rats fed an obesity-promoting diet, purple potatoes promised metabolic and cardiovascular benefits [79].

6. Vitamins and Nutritional Potential

6.1. Vitamin C

When it comes to the bioactive compounds in potato, we cannot ignore vitamin C, which has received the most attention. Vitamin C can be synthesized in the tuber part of the potato and transported to leaves and stems, where they then accumulate [80][81]. Potato generally contains 20 mg/100 g FW of vitamin C, which may account for up to 13% of the total antioxidant capacity. The recommended vitamin C intake per day for women (18–60 years old) is 60 mg. Potato (16.10 to 34.80 mg/100 g FW) [82][83] is a much better vitamin C source than cabbage (5.27 to 23.50 mg/100 g FW) [84] and even some kinds of tomato (8.26 to 22.54 mg/100 g FW) [85]. It should not be ignored as a crucial nutrient supplement based on vitamin C intake. Furthermore, in terms of the consumption rate and economical concerns, as well as storage conditions for vegetables, the potato could be the best choice for humans. As deficiency of iron has been a global problem, the consumption of potato with high vitamin C content might be a way to solve this problem.

Based on some research, the content of vitamin C is not only influenced by the potato variety, but also by the area and time of planting [86][87]. Much effort should be focused on maintaining vitamin C levels in cold storage since losses of up to 60% have been observed after cold storage [88][89]. By examining the vitamin C content in 12 potato genotypes after storing for 2, 4, and 7 months, a substantial loss after 4-month storage occurred, but several genotypes showed no significant loss after 2 months [90]. However, this contrasts markedly with a report that vitamin C increased as much as several-fold in 11 Indian potato varieties after storage [91]. It is highly desirable to find a cultivar that shows no loss after at least two months of storage. Other studies mentioned that compared with storage temperature, atmospheric oxygen levels have a greater effect on vitamin C levels [91].

Great care should be taken during processing because almost half the vitamin C is lost during pre-freezing, which can actually be avoided [92]. Therefore, optimizing processing and choosing proper methods to preserve crops is a practical measure to reduce the loss of vitamin C. Crop management also plays an important role in maximizing vitamin C, e.g., the use of high nitrogen fertilization reduces vitamin C levels, followed by a more rapid loss when the cut product is stored [93]. Consumers can choose potatoes with the peel to maximize phytonutrient intake. This theory proposes challenges for the food industry regarding how to improve the appearance and taste of the potatoes so that they can be widely accepted, as well as how to use the waste generated during processing and obtain more natural products, including antioxidants [94][95][96].

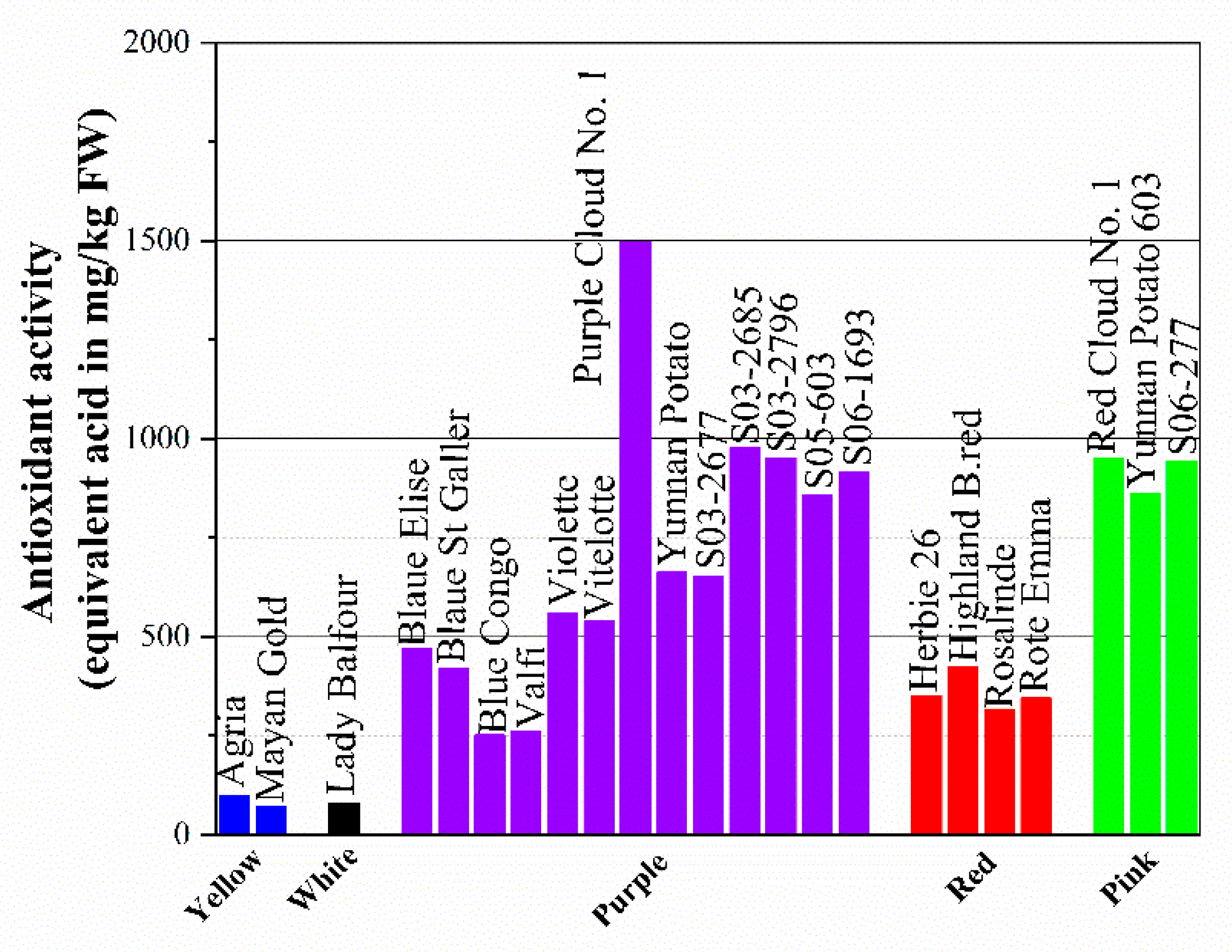

According to some studies, the hydrophilic antioxidant activity of totally pigmented red or purple potato is comparable to Brussels sprouts or spinach. Total anthocyanins range from 9 to 38 mg/100 g FW and ORAC varies from 7.6 and 14.2 μmole/g FW of Trolox equivalents. Meanwhile, potato generally contains 20 mg/100 g FW of vitamin C, which may account for up to 13% of the total antioxidant capacity. The total antioxidant activity (TAA) of potatoes was estimated using the ABTS radical cation method, and the DPPH assay is presented in Figure 4. It can be concluded from the figure that purple-fleshed potato has the highest total antioxidant activity among the selected colors with a range of 251 to 1497.6 equivalent ascorbic acid in mg/kg FW, followed by pink (860.3–948.6 equivalent ascorbic acid in mg/kg FW) and red (316.9–424.4 equivalent ascorbic acid in mg/kg FW). This means that colorless cultivars, including white-fleshed ones and light-yellow-fleshed potato, generally have relatively low antioxidant activity, which might be responsible for the low content of vitamin C, anthocyanins, and even phenolic compounds.

Figure 4. The total antioxidant activity (TAA) of potatoes was estimated using the ABTS radical cation method and DPPH assay.

Some other studies demonstrated a reverse effect of phytochemicals on various diseases (e.g., chronic inflammation, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes) [97]. Many of the compounds discussed above are present in higher concentrations in immature potatoes. This is because certain tuber nutrient contents decrease with the growth of the tuber. Baby potatoes (of golf ball size) have amounts of phenylpropanoids as much as 3-fold that of mature potatoes of the same cultivar, and higher amounts of carotenoids and various other phytonutrients [98]. The CGA content decreased 39–72% during development and varied among cultivars [98].

By investigating the effects of domestic cooking methods (boiling, baking, steaming, microwaving, frying, stir-frying, and air-frying) on the composition of phytochemicals (phenolics, anthocyanins, and carotenoids) in purple-fleshed potatoes, a reduction in the vitamin C, total phenolic, anthocyanin, and carotenoid contents was observed after cooking. Among these changes, the decrease in antioxidant activity was responsible for a reduction in the total phenolic content. The loss of vitamin C and phytochemicals was caused by frying methods but did not alter the antioxidant activity, which is likely due to the prevention of by-products of the Maillard reactions. It should be noted that steaming and microwaving have the potential to be used as a measure to retain phytochemicals and antioxidant activity [99]. Xu et al. (2009) also concluded that all cooking methods (boiling, baking, and microwaving) cause a decrease in antioxidant activity and phytochemical concentrations in potato [100]. In contrast, according to the report of Blessington et al. (2010), baking, frying, and microwaving can significantly increase the total phenolic content, chlorogenic acid content, and antioxidant activity in potatoes [101]. Faller and Fialho (2009) also showed that despite a significant increase in the total phenolic content, the antioxidant activity of potatoes decreased [102], whereas Burgos et al. proposed that boiling has a positive effect in enhancing the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity and has an obvious reverse effect on the total anthocyanin content. These differences might be attributed to the different cultivars and pretreatment methods and cooking conditions, as well as the nonuniformity of the analytical methods used [103]. More importantly, anthocyanin usually is unstable and can be significantly influenced by different pHs [104]. Therefore, more systematic studies of the effects of processing and cooking methods on phytochemicals are needed, especially on the functions such phytochemical compounds have in various diseases.

6.2. Vitamin B9

Folate (vitamin B9) deficiency is a worldwide concern that has a connection with birth defects [105]. Potatoes can be a source of dietary folate, providing 7–12% of the total folate in Dutch, Finnish, and Norwegian diets [106]. Increased consumption of potatoes can help to reduce the risk of low serum folate concentrations [107]. Folate concentrations in potatoes have been examined, which show that the content is significantly different among cultivars, with a range of 12–41 μg/100 g FW and 0.5–1.4 μg/g DW. Some wild species, such as S. Boliviense, contain 115 μg/100 g FW of folate [108][109][110].

6.3. Vitamin B6

Vitamin B6 is indispensable in a wide range of metabolic, physiological, and developmental processes and shows a high concentration in potatoes. The USDA’s Supertracker website released a medium potato that can provide 48% of the supplement of vitamin B6. Vitamin B6 deficiency can contribute to numerous health issues, including diabetes and neurological and skin disorders. The maturity of the potato is related to the degree of vitamin B6 present. According to the report by Mooney et al., vitamin B6 ranged from 16 to 27 μg/g DW in immature and mature tubers, respectively [111]. There is also a small proportion of thiamine (vitamin B1) in potatoes, with a concentration of 0.06–0.23 μg/100 g FW [109][112]. Thiamine content shows moderate broad-sense heritability, suggesting that breeding programs can be the first consideration for increasing its levels [113].

References

- Cesari, A.; Falcinelli, A.L.; Mendieta, J.R.; Pagano, M.R.; Mucci, N.; Daleo, G.R.; Guevara, M.G. Potato aspartic proteases (StAPs) exert cytotoxic activity on bovine and human spermatozoa. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 88, 1248–1255.

- Burgos, G.; Zum Felde, T.; Andre, C.; Kubow, S. The Potato and Its Contribution to the Human Diet and Health. Potato Crop Agric. Nutr. Soc. Contrib. Hum. 2020, 5, 73–74.

- Rommens, C.M.; Yan, H.; Swords, K.; Richael, C.; Ye, J. Low-acrylamide French fries and potato chips. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2008, 6, 843–853.

- Kaguongo, W.; Lungaho, C.; Borus, D.; Kipkoech, D.; Ng’Ang’A, N. A Policymakers’ Guide to Crop Diversification: The Case of the Potato in Kenya; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome: Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Camire, M.E.; Kubow, S.; Donnelly, D.J. Potatoes and Human Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 823–840.

- Visvanathan, R.; Jayathilake, C.; Jayawardana, B.; Liyanage, R. Health-beneficial properties of potato and compounds of interest. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4850–4860.

- Atkinson, F.S.; Foster-Powell, K.; Brand-Miller, J.C. International Tables of Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Values: 2008. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 2281–2283.

- Farhadnejad, H.; Teymoori, F.; Asghari, G.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F. The Association of Potato Intake with Risk for Incident Type 2 Diabetes in Adults. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42, 613–618.

- Khosravi-Boroujeni, H.; Mohammadifard, N.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; Sajjadi, F.; Maghroun, M.; Khosravi, A.; Alikhasi, H.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M.; Azadbakht, L. Potato consumption and cardiovascular disease risk factors among Iranian population. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 63, 913–920.

- Mozaffarian, D.; Hao, T.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Changes in Diet and Lifestyle and Long-Term Weight Gain in Women and Men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2392–2404.

- King, J.C.; Slavin, J.L. White Potatoes, Human Health, and Dietary Guidance. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 393–401.

- Huang, M.; Zhuang, P.; Jiao, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Potato consumption is prospectively associated with risk of hyper-tension: An 11.3-year longitudinal cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1936–1944.

- Aburto, N.J.; Hanson, S.; Gutierrez, H.; Hooper, L.; Elliott, P.; Cappuccio, F.P. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2013, 346, f1378.

- Albishi, T.; John, J.A.; Al-Khalifa, A.S.; Shahidi, F. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and DNA scission inhibitory activities of phenolic compounds in selected onion and potato varieties. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 930–939.

- Müller, H. Determination of the carotenoid content in selected vegetables and fruit by HPLC and photodiode array detection. Z. Lebensm. Forsch. A 1997, 204, 88–94.

- Nesterenko, S.; Sink, K.C. Carotenoid Profiles of Potato Breeding Lines and Selected Cultivars. Hortscience 2003, 38, 1173–1177.

- Burgos, G.; Salas, E.; Amoros, W.; Auqui, M.; Muñoa, L.; Kimura, M.; Bonierbale, M. Total and individual carotenoid profiles in Solanum phureja of cultivated potatoes: I. Concentrations and relationships as determined by spectrophotometry and HPLC. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2009, 22, 503–508.

- Kobayashi, A.; Ohara-Takada, A.; Tsuda, S.; Matsuura-Endo, C.; Takada, N.; Umemura, Y.; Nakao, T.; Yoshida, T.; Hayashi, K.; Mori, M. Breeding of potato variety “Inca-no-hitomi” with a very high carotenoid content. Breed. Sci. 2008, 58, 77–82.

- Hossain, A.; Begum, P.; Zannat, M.S.; Rahman, M.H.; Ahsan, M.; Islam, S.N. Nutrient composition of strawberry genotypes cul-tivated in a horticulture farm. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 648–652.

- Venkatachalam, K.; Rangasamy, R.; Krishnan, V. Total antioxidant activity and radical scavenging capacity of selected fruits and vegetables from south India. Int. Food Res. J. 2014, 21, 1003–1007.

- Chassy, A.W.; Bui, L.; Renaud, E.N.C.; Van Horn, M.; Mitchell, A.E. Three-year comparison of the content of antioxidant micro-constituents and several quality characteristics in organic and conventionally managed tomatoes and bell peppers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8244–8252.

- Valcarcel, J.; Reilly, K.; Gaffney, M.; O’brien, N. Total Carotenoids and l-Ascorbic Acid Content in 60 Varieties of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Grown in Ireland. Potato Res. 2014, 58, 29–41.

- Fernandez-Orozco, R.; Gallardo-Guerrero, L.; Hornero-Mendez, D. Carotenoid profiling in tubers of different potato (Solarium sp) cultivars: Accumulation of carotenoids mediated by xanthophyll esterification. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2864–2872.

- Brown, C.R. Antioxidants in potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 2005, 82, 163–172.

- Fraser, P.D.; Bramley, P.M. The biosynthesis and nutritional uses of carotenoids. Prog. Lipid Res. 2004, 43, 228–265.

- Gammone, M.A.; Riccioni, G.; D’Orazio, N. Carotenoids: Potential allies of cardiovascular health. Food Nutr. Res. 2015, 59, 26762–26771.

- Abdel-Aal, E.-S.M.; Akhtar, H.; Zaheer, K.; Ali, R. Dietary Sources of Lutein and Zeaxanthin Carotenoids and Their Role in Eye Health. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1169–1185.

- Chucair, A.J.; Rotstein, N.P.; SanGiovanni, J.P.; During, A.; Chew, E.Y.; Politi, L.E. Lutein and Zeaxanthin Protect Photoreceptors from Apoptosis Induced by Oxidative Stress: Relation with Docosahexaenoic Acid. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 5168–5177.

- Tan, J.S.; Wang, J.J.; Flood, V.; Rochtchina, E.; Smith, W.; Mitchell, P. Dietary Antioxidants and the Long-term Incidence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 334–341.

- Lu, S.; Li, L. Carotenoid metabolism: Biosynthesis, regulation, and beyond. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008, 50, 778–785.

- Cazzonelli, C.; Pogson, B. Source to sink: Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 266–274.

- Shewmaker, C.K.; Sheehy, J.A.; Daley, M.; Colburn, S.; Ke, D.Y. Seed-specific overexpression of phytoene synthase: Increase in carotenoids and other metabolic effects. Plant J. 1999, 20, 401–412.

- Fraser, P.D.; Romer, S.; Shipton, C.A.; Mills, P.B.; Kiano, J.W.; Misawa, N.; Drake, R.G.; Schuch, W.; Bramley, P.M. Evaluation of transgenic tomato plants expressing an additional phytoene synthase in a fruit-specific manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 99, 1092–1097.

- Ducreux, L.J.; Morris, W.; Hedley, L.; Shepherd, P.E. Metabolic engineering of high carotenoid potato tubers containing enhanced levels of b-carotene and lutein. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 81–89.

- Kato, M.; Matsumoto, H.; Ikoma, Y.; Okuda, H.; Yano, M. The role of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases in the regulation of carotenoid profiles during maturation in citrus fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 2153–2164.

- Campbell, R.; Ducreux, L.J.; Morris, W.L.; Morris, J.A.; Suttle, J.C.; Ramsay, G.; Bryan, G.J.; Hedley, P.E.; Taylor, M.A. The Metabolic and Developmental Roles of Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase4 from Potato. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 656–664.

- Haynes, K.G.; Clevidence, B.A.; Rao, D.; Vinyard, B.T.; White, J.M. Genotype environment interactions for potato tuber carotenoid content. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 135, 250–258.

- Brown, C.R.; Kim, T.S.; Ganga, Z.; Haynes, K.; De Jong, D.; Jahn, M.; Paran, I. Segregation of total carotenoid in high level potato germplasm and its relationship to beta-carotene hydroxylase polymorphism. Am. J. Potato Res. 2006, 83, 365–372.

- Wolters, A.M.A.; Uitdewilligen, J.G.; Kloosterman, B.A.; Hutten, R.C.B.; Visser, R.G.F.; Eck, H.J.V. Identification of alleles of ca-rotenoid pathway genes important for zeaxanthin accumulation in potato tubers. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 73, 659–671.

- Campbell, R.; Pont, S.D.A.; Morris, J.A.; McKenzie, G.; Sharma, S.K.; Hedley, P.E.; Ramsay, G.; Bryan, G.J.; Taylor, M.A. Genome-wide QTL and bulked transcriptomic analysis reveals new candidate genes for the control of tuber carotenoid content in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 1917–1933.

- Sulli, M.; Mandolino, G.; Sturaro, M.; Onofri, C.; Diretto, G.; Parisi, B.; Giuliano, G. Molecular and biochemical characterization of a potato collection with contrasting tuber carotenoid content. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 184–193.

- Diretto, G.; Al-Babili, S.; Tavazza, R.; Papacchioli, V.; Beyer, P.; Giuliano, G. Metabolic Engineering of Potato Carotenoid Content through Tuber-Specific Overexpression of a Bacterial Mini-Pathway. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, 350–361.

- Chitchumroonchokchai, C.; Diretto, G.; Parisi, B.; Giuliano, G.; Failla, M.L. Potential of golden potatoes to improve vitamin A and vitamin E status in developing countries. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 187–195.

- Im, H.W.; Suh, B.-S.; Lee, S.-U.; Kozukue, N.; Ohnisi-Kameyama, M.; Levin, C.E.; Friedman, M. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry in Potato Plant Flowers, Leaves, Stems, and Tubers and in Home-Processed Potatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3341–3349.

- Bassoli, B.K.; Cassolla, P.; Borba-Murad, G.R.; Constantin, J.; Salgueiro-Pagadigorria, C.L.; Bazotte, R.B.; Silva, R.S.D.S.F.D.; de Souza, H.M. Chlorogenic acid reduces the plasma glucose peak in the oral glucose tolerance test: Effects on hepatic glucose release and glycaemia. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2007, 26, 320–328.

- Niggeweg, R.; Michael, A.J.; Martin, C. Engineering plants with increased levels of the antioxidant chlorogenic acid. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 746–754.

- Payyavula, R.S.; Shakya, R.; Sengoda, V.G.; Munyaneza, J.E.; Swamy, P.; Navarre, D.A. Synthesis and regulation of chlorogenic acid in potato: Rerouting phenylpropanoid flux in HQT-silenced lines. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 13, 551–564.

- Payyavula, R.S.; Singh, R.K.; Navarre, D.A. Transcription factors, sucrose, and sucrose metabolic genes interact to regulate potato phenylpropanoid metabolism. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 5115–5131.

- Navarre, D.A.; Brown, C.R.; Sathuvalli, V.R. Potato Vitamins, Minerals and Phytonutrients from a Plant Biology Perspective. Am. J. Potato Res. 2019, 96, 111–126.

- Andre, C.M.; Ghislain, M.; Bertin, P.; Oufir, M.; Herrera, M.D.R.; Hoffmann, L.; Hausman, J.-F.; Larondelle, A.Y.; Evers, D. Andean Potato Cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.) as a Source of Antioxidant and Mineral Micronutrients. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 366–378.

- Ayvaz, H.; Bozdogan, A.; Giusti, M.M.; Mortas, M.; Gomez, R.; Rodriguez-Saona, L.E. Improving the screening of potato breeding lines for specific nutritional traits using portable mid-infrared spectroscopy and multivariate analysis. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 374–382.

- Valiñas, M.A.; Lanteri, M.L.; Have, A.T.; Andreu, A.B. Chlorogenic acid, anthocyanin and flavan-3-ol biosynthesis in flesh and skin of Andean potato tubers (Solanum tuberosum subsp. andigena). Food Chem. 2017, 229, 837–846.

- Kong, A.H.; Carolina, F.; Susan, H.; Andrés, C.; Antonio, V.G.; Roberto, L.M. Antioxidant capacity and total phenolic compounds of twelve selected potato landrace clones grown in Southern Chile. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 72, 3–9.

- Tudela, J.A.; Cantos, E.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Gil, M.I. Chemistry, induction of antioxidant flavonol bio-synthesis in fresh-cut potatoes. Effect of Domestic Cooking. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5925–5931.

- Kawabata, K.; Mukai, R.; Ishisaka, A. Quercetin and related polyphenols: New insights and implications for their bioactivity and bioavailability. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1399–1417.

- Yıldırım, S.; Kadıoğlu, A.; Sağlam, A.; Yaşar, A.; Sellitepe, H.E. Fast determination of anthocyanins and free pelargonidin in fruits, fruit juices, and fruit wines by high-performance liquid chromatography using a core-shell column. J. Sep. Sci. 2016, 39, 3927–3935.

- Wu, X.; Pittman, H.E.; Mckay, S.; Prior, R.L. Aglycones and Sugar Moieties Alter Anthocyanin Absorption and Metabolism after Berry Consumption in Weanling Pigs. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 2417–2424.

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Y.; He, J.; Zhu, Z. Transport of flavanolic monomers and procyanidin dimer A2 across human adeno-carcinoma stomach cells (MKN-28). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 3354–3362.

- Pęksa, A.; Miedzianka, J.; Nemś, A. Amino acid composition of flesh-coloured potatoes as affected by storage conditions. Food Chem. 2018, 266, 335–342.

- Jansen, G.; Flamme, W. Coloured potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.)—Anthocyanin content and tuber quality. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2006, 53, 1321–1331.

- Jung, C.S.; Griffiths, H.M.; Jong, D.M.D.; Cheng, S.; Bodis, M.; Jong, W.S.D. The potato P locus codes for flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 110, 269–275.

- Jung, C.S.; Griffiths, H.M.; De Jong, D.M.; Cheng, S.; Bodis, M.; Kim, T.S.; De Jong, W.S. The potato developer (D) locus encodes an R2R3 MYB transcription factor that regulates expression of multiple anthocyanin structural genes in tuber skin. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 120, 45–57.

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, S.; De Jong, D.; Griffiths, H.; Halitschke, R.; De Jong, W. The potato R locus codes for dihydroflavonol 4-reductase. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 119, 931–937.

- Payyavula, R.S.; Navarre, D.A.; Kuhl, J.; Pantoja, A. Developmental Effects on Phenolic, Flavonol, Anthocyanin, and Carotenoid Metabolites and Gene Expression in Potatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 7357–7365.

- Zhang, H.; Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Guo, D.; Hou, J.; Chen, S.; Song, B.; Xie, C. Analysis of structural genes and key transcription factors related to anthocyanin biosynthesis in potato tubers. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 310–316.

- Kyoungwon, C.; Kwang-Soo, C.; Hwang-Bae, S.; Jin, H.I.; Su-Young, H.; Hyerim, L.; Young-Mi, K.; Hee, N.M. Network analysis of the metabolome and transcriptome reveals novel regulation of potato pigmentation. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 1515–1533.

- Liu, Y.; Lin-Wang, K.; Deng, C.; Warran, B.; Wang, L.; Yu, B.; Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Espley, R.V.; Zhang, J.; et al. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of White and Purple Potato to Identify Genes Involved in Anthocyanin Biosynthesis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129148.

- Stushnoff, C.; Ducreux, L.J.M.; Hancock, R.D.; Hedley, P.E.; Holm, D.G.; McDougall, G.J.; McNicol, J.W.; Morris, J.; Morris, W.L.; Sungurtas, J.A.; et al. Flavonoid profiling and transcriptome analysis reveals new gene–metabolite correlations in tubers of Solanum tuberosum L. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 1225–1238.

- Tierno, R.; Ignacio, R.D.G. Jose, Characterization of high anthocyanin-producing tetraploid potato cultivars selected for breeding using morphological traits and microsatellite markers. Plant Genet. Resour. 2015, 15, 147–156.

- Charepalli, V.; Reddivari, L.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Vadde, R.; Agarwal, R.; Vanamala, J.K. Anthocyanin-containing purple-fleshed potatoes suppress colon tumorigenesis via elimination of colon cancer stem cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 1641–1649.

- Ombra, M.N.; Fratianni, F.; Granese, T.; Cardinale, F.; Cozzolino, A.; Nazzaro, F. In vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial and an-ti-proliferative activities of purple potato extracts (Solanum tuberosum cv Vitelotte noire) following simulated gastro-intestinal digestion. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1087–1091.

- Sido, A.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Kim, S.W.; Eriksson, E.; Shen, F.; Li, Q.; Bhat, V.; Reddivari, L.; Vanamala, J.K. A food-based approach that targets interleukin-6, a key regulator of chronic intestinal inflammation and colon carcinogenesis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 43, 11–17.

- Reddivari, L.; Vanamala, J.; Chintharlapalli, S.; Safe, S.H.; Miller, J.C., Jr. Anthocyanin fraction from potato extracts is cytotoxic to prostate cancer cells through activation of caspa-se-dependent and caspase-independent pathways. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 2227–2235.

- Zhao, X.; Sheng, F.; Zheng, J.; Liu, R. Composition and Stability of Anthocyanins from Purple Solanum tuberosum and Their Protective Influence on Cr(VI) Targeted to Bovine Serum Albumin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7902–7909.

- Jiang, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Xie, W.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Purple potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) anthocyanins attenuate alcohol-induced hepatic injury by enhancing antioxidant defense. J. Nat. Med. 2015, 70, 45–53.

- Kaspar, K.L.; Park, J.S.; Brown, C.R.; Mathison, B.D.; Navarre, D.A.; Chew, B.P. Pigmented Potato Consumption Alters Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Damage in Men. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 108–111.

- Vinson, J.A.; Demkosky, C.A.; A Navarre, D.; Smyda, M.A. High-Antioxidant Potatoes: Acute in Vivo Antioxidant Source and Hypotensive Agent in Humans after Supplementation to Hypertensive Subjects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 6749–6754.

- Ramdath, D.D.; Padhi, E.; Hawke, A.; Sivaramalingam, T.; Tsao, R. The glycemic index of pigmented potatoes is related to their polyphenol content. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 909–915.

- Ayoub, H.M.; McDonald, M.R.; Sullivan, J.A.; Tsao, R.; Platt, M.; Simpson, J.; Meckling, K.A. The Effect of Anthocyanin-Rich Purple Vegetable Diets on Metabolic Syndrome in Obese Zucker Rats. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 1240–1249.

- Viola, R.; Vreugdenhil, D.; Davies, H.; Sommerville, L. Accumulation of L-ascorbic acid in tuberising stolon tips of potato (Solanum tuberosum L). J. Plant Physiol. 1998, 152, 58–63.

- Tedone, L.; Hancock, R.D.; Alberino, S.; Haupt, S.; Viola, R. Long-distance transport of L-ascorbic acid in potato. BMC Plant Biol. 2004, 4, 16–20.

- Cabezas-Serrano, A.B.; Amodio, M.L.; Cornacchia, R.; Rinaldi, R.; Colelli, G. Suitability of five different potato cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.) to be processed as fresh-cut products. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009, 53, 138–144.

- Kaur, S.; Aggarwal, P. Evaluation of antioxidant phytochemicals in different genotypes of potato. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2014, 4, 167–172.

- Adelanwa, E.B.; Medugu, J.M. Variation in the nutrition composition of red and green cabbge (Brassica oleracea) with respect to age at harvest. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 7, 183–189.

- Bhandari, S.R.; Chae, Y.; Lee, J.G. Assessment of Phytochemicals, Quality Attributes, and Antioxidant Activities in Commercial Tomato Cultivars. Korean J. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 34, 677–691.

- Love, S.L.; Salaiz, T.; Shafii, B.; Price, W.J.; Mosley, A.R.; Thornton, R.E. Stability of Expression and Concentration of Ascorbic Acid in North American Potato Germplasm. Hortscience 2004, 39, 156–160.

- Love, S.L.; Pavek, J.J. Positioning the Potato as a Primary Food Source of Vitamin C. Am. J. Potato Res. 2008, 85, 277–285.

- Keijbets, M.J.H.; Ebbenhorst-Seller, G. Loss of vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid) during long-term cold storage of Dutch table potatoes. Potato Res. 1990, 33, 125–130.

- Dale, M.F.B.; Griffiths, D.W.; Todd, D.T. Effects of genotype, environment, and postharvest storage on the total ascorbate content of potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 244–248.

- Külen, O.; Stushnoff, C.; Holm, D.G. Effect of cold storage on total phenolics content, antioxidant activity and vitamin C level of selected potato clones. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 2437–2444.

- Blauer, J.M.; Kumar, G.M.; Knowles, L.O.; Dhingra, A.; Knowles, N. Changes in ascorbate and associated gene expression during development and storage of potato tubers (Solanum tuberosum L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 78, 76–91.

- Tosun, B.N.; Yücecan, S. Influence of commercial freezing and storage on vitamin C content of some vegetables. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 43, 316–321.

- Licciardello, F.; Lombardo, S.; Rizzo, V.; Pitino, I.; Pandino, G.; Strano, M.G.; Muratore, G.; Restuccia, C.; Mauromicale, G. Integrated agronomical and technological approach for the quality maintenance of ready-to-fry potato sticks during refrigerated storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 136, 23–30.

- Amado, I.R.; Franco, D.; Sanchez, M.; Zapata, C.; Vazquez, J.A. Optimisation of antioxidant extraction from Solarium tuberosum potato peel waste by surface response methodology. Food Chem. 2014, 165, 290–299.

- López-Cobo, A.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Cerretani, L.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Distribution of phenolic compounds and other polar compounds in the tuber of Solanum tuberosum L. by HPLC-DAD-q-TOF and study of their an-tioxidant activity. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2014, 36, 1–11.

- Nara, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Honma, T.; Koga, H. Antioxidative Activity of Bound-Form Phenolics in Potato Peel. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 1489–1491.

- Williams, D.J.; Edwards, D.; Hamernig, I.; Jian, L.; James, A.P.; Johnson, S.K.; Tapsell, L.C. Vegetables containing phytochemicals with potential anti-obesity properties: A review. Food Res. Int. 2013, 52, 323–333.

- Navarre, D.A.; Payyavula, R.S.; Shakya, R.; Knowles, N.R.; Pillai, S.S. Changes in potato phenylpropanoid metabolism during tuber development. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 65, 89–101.

- Tian, J.; Chen, J.; Lv, F.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Ye, X. Domestic cooking methods affect the phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of purple-fleshed potatoes. Food Chem. 2015, 197, 1264–1270.

- Xu, X.; Li, W.; Lu, Z.; Beta, T.; Hydamaka, A.W. Phenolic Content, Composition, Antioxidant Activity, and Their Changes during Domestic Cooking of Potatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10231–10238.

- Blessington, T.; Nzaramba, M.N.; Scheuring, D.C.; Hale, A.L.; Reddivari, L.; Miller, J.C. Cooking Methods and Storage Treatments of Potato: Effects on Carotenoids, Antioxidant Activity, and Phenolics. Am. J. Potato Res. 2010, 87, 479–491.

- Faller, A.; Fialho, E. The antioxidant capacity and polyphenol content of organic and conventional retail vegetables after domestic cooking. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 210–215.

- Burgos, G.; Amoros, W.; Muñoa, L.; Sosa, P.; Cayhualla, E.; Sanchez, C.; Díaz, C.; Bonierbale, M. Total phenolic, total anthocyanin and phenolic acid concentrations and antioxidant activity of purple-fleshed potatoes as affected by boiling. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 30, 6–12.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tao, C.; Liu, M.; Pan, Y.; Lv, Z. Effect of temperature and pH on stability of anthocyanin obtained from blueberry. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 1744–1753.

- Blancquaert, D.; Storozhenko, S.; Loizeau, K.; De Steur, H.; De Brouwer, V.; Viaene, J.; Ravanel, S.; Rébeillé, F.; Lambert, W.; Van Der Straeten, D. Folates and Folic Acid: From Fundamental Research Toward Sustainable Health. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2010, 29, 14–35.

- Alfthan, G.; Laurinen, M.S.; Valsta, L.M.; Pastinen, T.; Aro, A. Folate intake, plasma folate and homocysteine status in a random Finnish population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 81–88.

- Hatzis, C.M.; Bertsias, G.K.; Linardakis, M.; Scott, J.M.; Kafatos, A.G. Dietary and other lifestyle correlates of serum folate con-centrations in a healthy adult population in Crete, Greece: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2006, 5, 105–113.

- Goyer, A.; Navarre, D.A. Determination of Folate Concentrations in Diverse Potato Germplasm Using a Trienzyme Extraction and a Microbiological Assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 3523–3528.

- Goyer, A.; Sweek, K. Genetic Diversity of Thiamin and Folate in Primitive Cultivated and Wild Potato (Solanum) Species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 13072–13080.

- Kuhn, D.N.; Chappell, J.; Boudet, A.; Hahlbrock, K. Induction of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase and 4-coumarate: CoA ligase mRNAs in cultured plant cells by UV light or fungal elicitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 1102–1106.

- Mooney, S.; Chen, L.; Kühn, C.; Navarre, R.; Knowles, N.R.; Hellmann, H. Genotype-Specific Changes in Vitamin B6 Content and the PDX Family in Potato. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 389723.

- Holland, B.; Unwin, I.D.; Buss, D.H. Vegetables, herbs and spices. Nutr. Bull. 1991, 16, 386–414.

- Goyer, A.; Haynes, K.G. Vitamin B1 Content in Potato: Effect of Genotype, Tuber Enlargement, and Storage, and Estimation of Stability and Broad-Sense Heritability. Am. J. Potato Res. 2011, 88, 374–385.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.3K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

08 Jun 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No