Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zishan Zhang | -- | 3813 | 2023-06-01 16:35:38 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | Meta information modification | 3813 | 2023-06-05 03:32:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Z. Factors Affecting Dynamic Photosynthesis under Changing Light. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45112 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Li Y, Gao H, Zhang Z. Factors Affecting Dynamic Photosynthesis under Changing Light. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45112. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Li, Yu-Ting, Hui-Yuan Gao, Zishan Zhang. "Factors Affecting Dynamic Photosynthesis under Changing Light" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45112 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Li, Y., Gao, H., & Zhang, Z. (2023, June 01). Factors Affecting Dynamic Photosynthesis under Changing Light. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45112

Li, Yu-Ting, et al. "Factors Affecting Dynamic Photosynthesis under Changing Light." Encyclopedia. Web. 01 June, 2023.

Copy Citation

Major research on photosynthesis has been carried out under steady light. However, in the natural environment, steady light is rare, and light intensity is always changing. Changing light affects (usually reduces) photosynthetic carbon assimilation and causes decreases in biomass and yield. Ecologists first observed the importance of changing light for plant growth in the understory; other researchers noticed that changing light in the crop canopy also seriously affects yield.

photosynthetic carbon assimilation

changing light

fluctuating light

1. Introduction

Light is the unique driving force of photosynthesis in plants; the rate of photosynthetic carbon assimilation is controlled by light intensity. Compared with other environmental factors controlling photosynthesis, such as temperature and carbon dioxide concentration, light intensity is distinguished by its more frequent, faster and larger variations. With the rotation and revolution of the earth, sunlight intensity changes daily and seasonally. In addition, the light intensity received by leaves also changes due to accidental events, such as wind, the shade caused by clouds and neighboring leaves and plants, etc. [1][2]. In terrestrial ecosystems, these changes in light intensity generally occur at temporal scales ranging from less than a second to several minutes.

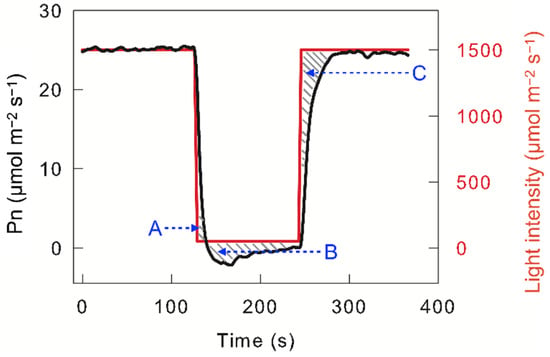

Photosynthetic carbon assimilation changes with changing light intensity, which is known as “dynamic photosynthetic carbon assimilation” or “dynamic photosynthesis”. Dynamic photosynthesis does not fully conform to the change trend predicted by the light intensity response curve of the net photosynthetic carbon assimilation rate (Pn) [3][4], which is mainly due to photosynthetic carbon assimilation lag in response to light intensity. When high-light-adapted leaves were exposed to darkness or low light, photosynthetic carbon assimilation did not cease immediately but continued for a short time (seconds to tens of seconds); this excess photosynthetic carbon assimilation is termed “post-irradiance carbon assimilation” (Area A in Figure 1). Next, Pn decreased to a lower value than that observed under steady low light or darkness, which is due to carbon dioxide release during photorespiration; this excess carbon dioxide release is defined as “post-irradiance carbon burst“ (Area B in Figure 1). When the light intensity changes from darkness or low light to high light, Pn does not immediately reach steady high-light levels, but gradually increases in tens of seconds to minutes. This loss in photosynthetic carbon assimilation in the photosynthetic induction stage is reflected in the C area in Figure 1. Usually, the loss in photosynthetic carbon assimilation in the photosynthetic induction stage is much more than the post-irradiance carbon assimilation; hence, changing light usually leads to a loss in photosynthetic carbon assimilation. Combining the measured results with the prediction model, the loss in photosynthetic carbon assimilation caused by changing light may be as high as 20% or more [3][5]. Such losses unavoidably decrease crop yield. On the other hand, if the photosynthetic loss caused by changing light can be reduced, the crop yield is significantly improved.

Figure 1. Light intensity and dynamic net photosynthetic carbon assimilation rate (Pn) in leaves of C3 species Triticum aestivum. The A area indicates post-irradiance carbon assimilation; the B area indicates the post-irradiance carbon burst; the C area indicates the loss in photosynthetic carbon assimilation in the photosynthetic induction stage.

2. Effects of Environmental Factors on Dynamic Photosynthesis under Changing Light

2.1. Growth Light Environment

Tang et al. reported that the leaves of Quercus serrata seedlings grown in a microsite with a lower sunfleck light intensity and a shorter sunfleck duration showed a more rapid photosynthetic induction [6]. Tinoco-Ojanguren and Pearcy compared the photosynthetic induction of Piper auritum, a pioneer tree species, grown on an open bench with (1% full sun) or without (60% full sun) a neutral shade cloth enclosure; the results showed that the photosynthetic induction was faster in shaded plants than in sunned plants [7]. Küppers et al. reported that the leaves from plants grown in more open regions took less time to become half-induced under saturating light than the leaves from plants grown in more shaded regions [8]. Pseudotsuga menziesii seedlings grown in the open had a higher photosynthetic carbon assimilation rate under steady light but slower photosynthetic induction than seedlings grown in the forest understory [9]. Nilsen et al. observed that photosynthesis reached 50% induction in 159 s for Quercus rubra seedlings grown in forest patches without shrubs compared with 226 s for seedlings grown in forest patches with shrubs present [10]. Durand et al. found that shade leaves of Fagus sylvatica complete full induction in a shorter time than sun leaves, but that sun leaves respond faster to high light than shade leaves due to their much larger amplitude of induction [11]. Wu et al. reported that increased planting density of Zea mays enhanced the change frequency of light and reduced the duration of daily high light; in addition, photosynthetic induction was significantly accelerated in Zea mays plants grown at a higher planting density [12].

In general, the above results show that plants or leaves grown in shaded regions have faster photosynthetic induction and maintain a higher induction state over longer periods in low light or darkness than plants grown in open regions. However, many different results have also been reported. Tausz et al. reported that canopy leaves had higher photosynthetic capacity under steady light, faster photosynthetic induction and took less time to reach 90% of the maximum Pn compared with coppice leaves of Nothofagus cunninghamii [13]. Leakey et al. reported that rates of photosynthetic induction were similar in Shorea leprosula and Hopea nervosa plants grown under long and short sunfleck conditions [14]. Sims and Pearcy showed that the understory species Alocasia macrorrhiza grown under short lightflecks, long lightflecks and uniform diffuse-light regimes showed similar steady photosynthetic capacity and lightfleck-use efficiency [15]. Research from Rijkers et al. showed that growth regimes (bright gaps and shaded understory) affected the maximum net photosynthesis rate rather than the photosynthetic induction rate in three shade-tolerant tree species [16].

In most experiments under natural or semi-natural conditions, the variation in mean light intensity and the change frequency of growth light were not completely distinguished. For example, compared with open sites, an understory environment usually represents lower mean light intensity and higher frequency change in light intensity [8][9][14]. Although in situ experiments provide abundant and real information, experiments performed in controlled environments are necessary. Qiao et al. reported that in Zea mays seedlings, a faster change frequency of growth light accelerated photosynthetic induction under high-light conditions following 3 min of weak light [17]. Tang et al. reported that plants grown under low light or lightfleck had faster photosynthetic induction than plants grown under high light [18].

It was also reported that photosynthetic induction was slower in Arabidopsis thaliana grown in sinusoidal high light than plants grown in changing light regimes [19]. However, Vialet-Chabrand et al. reported that plants grown under changing light conditions utilized the changing light less, not more efficiently, than plants grown under steady light [4]. It was also reported that the change frequency [20] and intensity of growth light [4] rarely affected dynamic photosynthetic properties in Solanum lycopersicum and Arabidopsis thaliana, respectively.

The above results indicate that the effect of growth light environment on photosynthetic response to changing light is species-dependent [21][22][23].

2.2. Drought and Salt

Drought stress reduced the Pn of Oryza sativa under steady high light but had a weak impact on Pn under steady low light [24]. Interestingly, drought stress did not affect the time required to reach 50 or 90% of the maximum Pn after transitioning from low light to high light, but significantly decreased Pn in the low-light stage of changing light [24]. Sakoda et al. reported that drought stress delayed photosynthetic induction in Oryza sativa and Glycine max but only slightly interfered with maximum Pn values under steady high light [25]. Both studies emphasized the limitation of stomatal factors on dynamic photosynthesis under drought stress [24][25]. Sun et al. reported that drought stress delayed photosynthetic induction in Solanum lycopersicum [26].

Zhang et al. showed that salt stress did not affect Pn under steady high light but decelerated photosynthetic induction in Solanum lycopersicum [27]. However, two years later, the group reported an opposite result: salt stress suppressed Pn under steady high light but did not affect photosynthetic induction and Pn in Solanum lycopersicum [20]. This difference may have been caused by different salt concentrations and treatment durations.

In summary, dynamic photosynthesis is more sensitive to drought and salt stresses than steady photosynthesis; drought and salt stresses significantly increase the photosynthetic loss caused by changing light.

2.3. Air Temperature and Air Humidity

High temperature inhibited Pn more seriously under changing light than steady light conditions in Shorea leprosula and Oryza sativa seedlings [28][29]. High temperature also decelerated photosynthetic induction in Oryza sativa [30]. Research by Kang et al. showed that the effect of high temperature on photosynthetic induction was species-dependent: raising the temperature from 30 °C to 40 °C decelerated photosynthetic induction in Croton argyratus, Shorea leprosula and Lepisanthes senegalensis, but accelerated photosynthetic induction in Neobalanocarpus heimii [31].

Kaiser et al. reported that a decrease in temperature from 30.5 °C to 15.5 °C mildly delayed photosynthetic induction in Solanum lycopersicum [32]. The same study showed that raising leaf-to-air vapor pressure deficits from 0.5 to 2.3 kPa did not affect photosynthetic induction in Solanum lycopersicum [32]. In contrast, Tinoco-Ojanguren and Pearcy reported that a higher leaf–air vapor pressure deficit did not affect the photosynthetic carbon assimilation under steady high or low light, but significantly delayed photosynthetic induction in two rainforest Piper species [7].

Hence, dynamic photosynthesis is more sensitive to suboptimal temperature and humidity than steady photosynthesis, and the response of dynamic photosynthesis to suboptimal temperature and humidity is species dependent.

2.4. Carbon Dioxide Concentration

Elevated carbon dioxide concentrations led to an increase in the induction state 60 s after leaf illumination by 129% and 108% in broadleaved Fagus sylvatica and coniferous Picea abies, respectively, but elevated carbon dioxide concentrations decreased the time required to reach 90% of the maximum Pn by 5–15% and 21–28% in Fagus sylvatica and Picea abies, respectively, indicating that the acceleration during the initial stage of photosynthetic initiation was more significant than that during the later stage of photosynthetic initiation [33]. Populus species grown under conditions of higher carbon dioxide had a higher photosynthetic induction state, a shorter induction time, and reduced induction limitation to photosynthetic carbon assimilation after the plants were transferred from low to high light under growth carbon dioxide concentration [34]. A similar result was observed in Shorea leprosula [35]. Temporarily elevated carbon dioxide concentrations also accelerated photosynthetic induction and photosynthetic carbon assimilation under changing light conditions in Dipterocarpus sublamellatus [36] and Solanum lycopersicum [37]. Temporary low carbon dioxide (20 Pa) levels delayed photosynthetic induction in Solanum lycopersicum [32]. Kang et al. reported that both long-term and temporarily elevated carbon dioxide concentrations accelerated photosynthetic induction, though the acclimation of plants to high carbon dioxide reduced the acceleration of photosynthetic induction [38]. The above results clearly indicate that increased carbon dioxide concentrations not only increase the maximum photosynthetic capacity under steady high light, but also reduce the loss in Pn caused by changes in light intensity.

2.5. Nitrogen Nutrition

High nitrogen supply accelerated photosynthetic induction in Solanum lycopersicum and Zea mays [39][40]. A greater nitrogen supply improved the rapid response of Pn to changing light in Oryza sativa; the loss in Pn caused by changing light was relieved by increased nitrogen supply [29][41]. However, Li et al. observed the opposite result in Glycine max: although reducing nitrogen supply reduced photosynthesis under steady light, it alleviated the loss in Pn in changing light compared with that in steady light, which was attributed to the relative excess of RuBP regeneration-related enzymes in low-nitrogen leaves [42]. The effect of other nutrients on dynamic photosynthesis under changing light is still unclear, although many studies have shown that various nutrients significantly affect photosynthesis under steady light [43][44][45].

2.6. Circadian Rhythm

Dynamic photosynthesis under changing light is more sensitive to circadian rhythms than steady photosynthesis. In Arabidopsis thaliana planted in a changing light regime, the time constant for the light-saturated rate of carbon assimilation was highest in the evening and lower in the morning; the lowest value was recorded at midday [19]. Küppers et al. showed that the photosynthetic induction in Pothos scandens was faster in the early morning and at night than that at midday, and that the photosynthetic induction in another species, Hydnocarpus pentandra, was faster at night than in the morning and afternoon [8]. Poorter and Oberbauer reported that photosynthetic induction in Dipteryx panamensis and Cecropia obtusifolia with different successional traits was much faster in the morning than in the afternoon; however, the light-saturated steady-state photosynthetic rate was consistent at different times of day [21]. A similar result was reported by Robert and Pearcy [46][47]. These research works indicate that the effect of circadian rhythms on dynamic photosynthesis is species dependent.

3. Effects of Non-Environmental Factors on Dynamic Photosynthesis under Changing Light

3.1. C3 and C4 Photosynthetic Type

Pearcy et al. first studied dynamic photosynthesis under changing light in C3 and C4 tree species [48]. They observed that the effect of light change on Pn was similar in C3 and C4 tree species. Later, Pearcy and his colleagues analyzed the photosynthesis of the C4 species Zea mays under lightfleck [49] and compared it with selected C3 species [47][50][51]. It was observed that maize utilized lightfleck more efficiently than the C3 species. Kubásek et al. reported that the carbon assimilation loss and growth slowdown caused by changing light were more serious in two C4 species than in two C3 species [52]. The comparison of 18 C3 and C4 species, including C3, C4, C4-like and C3–C4 intermediate (C2) species in the Flaveria genus, showed that C4 plants have a significantly lower photosynthetic utilization efficiency of changing light than C3 plants; in addition, the C4-like Flaveria species had similar behavior to that of C4 Flaveria species, and the C3–C4 intermediate Flaveria species had similar behavior to that of the C3 Flaveria species [53]. However, Lee et al. reported the opposite result: six C4 bioenergy grasses utilized changing light better than six C3 bioenergy grasses [54]. Recent research in three phylogenetically linked pairs of C3 and C4 species from the Alloteropsis, Flaveria and Cleome genera indicated that photosynthetic induction was slower in C4 than in C3 species [55].

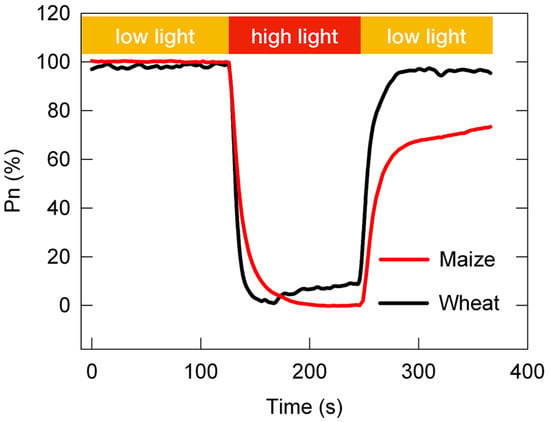

At present, the adaptability of C3 and C4 plants to changing light is still an open question. As shown in Figure 2, the post-irradiance carbon burst was negligible in NADP-ME-type C4 species, and the post-irradiance carbon assimilation was higher in NADP-ME-type C4 species than in C3 species; however, the loss in photosynthetic carbon assimilation in the photosynthetic induction stage was much greater in NADP-ME-type C4 species than in C3 species [53][54]. In other words, compared with C3 plants, C4 plants fix more carbon dioxide during low-light periods of changing light, while C4 plants fix less carbon dioxide during high-light periods of changing light. Some scholars propose that C4 photosynthesis may be both more and less resilient than C3 to changing light conditions, depending on the frequency at which these light changes occur [56]. They speculate that C4 photosynthesis may have more advantages than C3 photosynthesis under high-frequency changing light (10–15 s or less).

Figure 2. The dynamic net photosynthetic carbon assimilation rate (Pn) in leaves of the C3 species Triticum aestivum and the C4 species Zea mays. The relative Pn curve was obtained from the standardization between the Pn under constant high light (100%) and the minimum Pn under constant low light (0%).

Most studies on C4 plants have focused on their advantages over C3 plants, pointing to their high-temperature resistance, water conservation ability and high yield, and have proposed grand plans for engineering C4 photosynthesis into C3 plants [57][58], including the “C4 rice project” [59].

3.2. Inter-Specific Variations

Valladares et al. reported that “leaves of understory species showed the most rapid induction and remained induced longer once transferred to the shade than did leaves of medium- or high-light species” [60]. Leakey et al. reported that photosynthetic induction was faster in shade-tolerant dipterocarp species than in less shade-tolerant species [14]. Early successional species showed the slowest photosynthetic induction, while mid-successional species showed the fastest photosynthetic induction, and the rate of photosynthetic induction in late-successional species was between those of early-successional and mid-successional species [61]. Küppers et al. showed that late-successional species had faster photosynthetic induction in continuous saturated light following darkness, and a slower loss in induction in darkness following high light than early-successional species [8].

It was reported that photosynthetic induction was faster in four fern species than in three woody species [23]. The loss in photosynthetic carbon assimilation during photosynthetic induction was less in fern species than in gymnosperm and angiosperm species [62].

In general, shade-tolerant species and late-successional species have a higher photosynthetic energy utilization efficiency under changing light than heliophilic species and early successional species.

3.3. Intra-Specific Variations

In order to improve the photosynthetic light energy utilization efficiency of crops by utilizing natural genetic variation, dynamic photosynthesis under changing light was compared among various cultivars of crop species, including Oryza sativa [63][64][65][66], Oryza glaberrima [67], Triticum aestivum [68], Glycine max [69][70], Musa nana [71], Manihot esculenta [72], Brassica napus [73] and Rosa rugosa [74].

Generally, the variation in photosynthetic carbon assimilation among cultivars in changing light conditions greatly exceeded that in steady light conditions [64][66][67][68][69][72][73][74]. Acevedo-Siaca et al. reported that although wild progenitors of Oryza sativa had lower Pn under steady high light than cultivated Oryza sativa, wild Oryza sativa assimilated 16– 40% more carbon dioxide than cultivated Oryza sativa [65]. Moreover, there was no significant correlation between steady and dynamic photosynthetic traits [66][70].

Researchers have also attempted to explain intra-specific variations in photosynthetic induction. Intra-specific variations in photosynthetic induction were mainly attributed to the activation rate of Rubisco [64][66][69][70]. Liu et al. reported that the rate of photosynthetic induction was positively correlated with the nitrogen content and Rubisco content in leaves of Brassica napus [73]. Soleh et al. also reported the activation rate of Rubisco was related to the single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the Rubisco activase gene [69]. In contrast, research on Oryza sativa [75], Musa nana [71] and Manihot esculenta [72] showed that stomatal conductance was the major limitation to dynamic photosynthesis under changing light conditions. Adachi et al. reported that the faster induction response to sudden increases in light intensity in a high-yield Oryza sativa cultivar (Takanari), compared with a cultivar with lower yield (Koshihikari), was explained in part by the maintenance of a larger pool of Calvin–Benson cycle metabolites in Takanari [63].

3.4. Stomatal Behavior

The response rate of stomatal opening to changes in light intensity is slower than that of photosynthetic carbon assimilation [76][77]. Pre-opening stomata under low light or darkness could accelerate photosynthetic induction under high-light conditions [22][46][47][78][79]. However, recent research showed that pre-dawn stomatal opening does not substantially enhance photosynthetic induction in Helianthus annuus [80]. It has also been reported that smaller and denser stomata contributed to a faster stomatal response under changing light, resulting in improved photosynthetic induction [75][81][82]. The stomatal closure rate also affects dynamic photosynthesis under changing light conditions. Delayed stomatal closure, similar to stomatal pre-opening, accelerates photosynthetic induction following an increase in light intensity. However, it also increases water loss, and limits long-term photosynthetic carbon assimilation under water-restricted conditions [83].

More direct evidence on the contribution of stomata to photosynthetic carbon assimilation under changing light comes from comparisons of dynamic photosynthesis between wild-type and transgenic or mutant plants with specifically modified stomatal characteristics. The abscisic acid-deficient flacca mutant of Solanum lycopersicum displayed very high stomatal conductance and faster photosynthetic induction than the wild-type [84]. The STOMAGEN-overexpressing Arabidopsis thaliana line (ST-OX) and the EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR 1 knockout line (epf1) showed faster photosynthesis induction than the wild-type after a step increase in light, owing to their higher stomatal conductance under initial dark conditions; however, there were no significant variations in photosynthetic carbon assimilation under steady light between the wild-type and ST-OX or epf1 [85]. SLAC1 encodes a stomatal anion channel that regulates stomatal closure; a deficiency of SLAC1 in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana significantly accelerated stomatal opening, photosynthetic induction and plant growth in changing light conditions [86][87]. Open stomata 1 (ost1) mutants always open stomata even under darkness; the PROTON ATPASE TRANSLOCATION CONTROL 1 overexpression line (PATROL1) closed and opened stomata faster than wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana; hence, ost1 and PATROL1 assimilated more carbon dioxide and accumulated more dry weight under changing light conditions rather than in constant light [87]. The BLINK1 gene encodes a light-gated K+ channel in guard cells. BLINK1 overexpression in Arabidopsis thaliana accelerated both stomatal opening under light exposure and closing after irradiation; moreover, it drove a 2.2-fold increase in biomass in changing light conditions [88].

The above results unanimously indicate that reducing stomatal limitations can effectively improve photosynthetic carbon assimilation, especially under changing light conditions, although it may lead to a decrease in water-use efficiency. Therefore, the most effective method is to accelerate the response rate of stomata to changes in light intensity, rather than increasing the opening of stomata.

3.5. Other Genes

In addition to the genes mentioned above that dominate stomatal development and affect dynamic photosynthesis under a changing light environment, researchers have also found more genes that influence dynamic photosynthesis.

Non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) is an important photoprotection mechanism of PSII, and even of PSI; it gradually activates under light and relaxes in darkness and low light [89]. Modeling analysis predicted that accelerating the relaxation of NPQ during transferal from high to low light could enhance photosynthetic carbon assimilation under low-light conditions [90][91]. Compared with the wild-type, NPQ was enhanced and the photosynthetic induction was decelerated with PsbS gene overexpression in Oryza sativa, a gene which encodes a key protein of NPQ; the opposite result occurred in RNAi lines [92]. Surprisingly, the simultaneous overexpression of three key genes of NPQ, PsbS, violaxanthin deepoxidase (VDE) and zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZE), accelerated the relaxation of NPQ and enhanced post-irradiance carbon assimilation, thus improving biomass and yield in changing light conditions. Similar phenomena were observed in Nicotiana tabacum [93] and Glycine max [94]. Unfortunately, similar genetic improvements failed to improve, and even suppressed photosynthetic carbon assimilation and dry matter accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana [95] and Solanum tuberosum [96]. These results indicate that the effects of accelerated NPQ relaxation on photosynthesis and growth are species-dependent.

Overexpression of the flavodiiron gene from Physcomitrium patens in Arabidopsis thaliana enhanced growth in changing light conditions by increasing photosynthetic carbon assimilation in the high-light phase of changing light conditions [97]. The deregulation K+ exchange antiporter 3 (KEA3) gene in Arabidopsis thaliana increased photosynthetic carbon assimilation during photosynthetic induction [98].

Overexpression of the Rubisco activase (RCA) gene accelerated photosynthetic induction in Oryza sativa, especially at high temperatures [30]. Researchers modified the gene sequence of RCA at different sites to render RCA continuously activated, even in the dark; the transformant of Arabidopsis thaliana that expresses modified RCA had accelerated photosynthetic induction and enhanced growth in changing light [99][100]. Moreover, McCormick and Kruger reported that the mutant of the cytosolic 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (F2KP) gene had normal Pn under steady light but exhibited delayed photosynthetic induction [101]. The C4 species Setaria viridis overexpressed pyruvate phosphate dikinase regulatory proteins (PDRP) and kept pyruvate phosphate dikinase (PPDK) active even under darkness but delayed photosynthetic induction, which is due to the exhaustion of pyruvate [102].

Recent research has shown that the Pn of a chlorophyll-deficient Glycine max mutant was similar under steady light but was more responsive to changing light than wild-type Glycine max [103]. However, Ferroni et al. reported that chlorophyll-depleted mutants and wild-type Triticum aestivum had comparable adaptation to changing light [104].

Researchers have improved photosynthetic carbon assimilation under changing light conditions through a variety of synthetic biology methods. However, further research is needed to determine whether these methods can be extended to different crops.

References

- Tang, Y.H.; Washitani, I.; Tsuchiya, T.; Iwaki, H. Fluctuation of photosynthetic photon flux density within a Miscanthus sinensis canopy. Ecol. Res. 1988, 3, 253–266.

- Nishimura, S.; Koizumi, H.; Tang, Y. Spatial and temporal variation in photon flux density on rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaf surface. Plant Prod. Sci. 1998, 1, 30–36.

- Taylor, S.H.; Long, S.P. Slow induction of photosynthesis on shade to sun transitions in wheat may cost at least 21% of productivity. Philos. T. R. Soc. B 2017, 372, 20160543.

- Vialet-Chabrand, S.; Matthews, J.S.; Simkin, A.J.; Raines, C.A.; Lawson, T. Importance of fluctuations in light on plant photosynthetic acclimation. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 2163–2179.

- Morales, A.; Kaiser, E.; Yin, X.; Harbinson, J.; Molenaar, J.; Driever, S.M.; Struik, P.C. Dynamic modelling of limitations on improving leaf CO2 assimilation under fluctuating irradiance. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 589–604.

- Tang, Y.; Hiroshi, K.; Izumi, W.; Hideo, I. A preliminary study on the photosynthetic induction response of Quercus serrata seedlings. J. Plant Res. 1993, 106, 219–222.

- Tinoco-Ojanguren, C.; Pearcy, R.W. Stomatal dynamics and its importance to carbon gain in two rainforest Piper species: II. Stomatal versus biochemical limitations during photosynthetic induction. Oecologia 1993, 94, 395–402.

- Küppers, M.; Timm, H.; Orth, F.; Stegemann, J.; Stöber, R.; Schneider, H.; Paliwal, K.; Karunaichamy, K.S.T.K.; Ortiz, R. Effects of light environment and successional status on lightfleck use by understory trees of temperate and tropical forests. Tree Physiol. 1996, 16, 69–80.

- Chen, H.Y.; Klinka, K. Light availability and photosynthesis of Pseudotsuga menziesii seedlings grown in the open and in the forest understory. Tree Physiol. 1997, 17, 23–29.

- Nilsen, E.T.; Lei, T.T.; Semones, S.W. Presence of understory shrubs constrains carbon gain in sunflecks by advance-regeneration seedlings: Evidence from Quercus rubra seedlings growing in understory forest patches with or without evergreen shrubs present. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2009, 170, 735–747.

- Durand, M.; Stangl, Z.R.; Salmon, Y.; Burgess, A.J.; Murchie, E.H.; Robson, T.M. Sunflecks in the upper canopy: Dynamics of light-use efficiency in sun and shade leaves of Fagus sylvatica. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 1365–1378.

- Wu, H.Y.; Qiao, M.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Kang, W.J.; Ma, Q.H.; Gao, H.Y.; Zhang, W.F.; Jiang, C.D. Photosynthetic mechanism of maize yield under fluctuating light environments in the field. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 957–973.

- Tausz, M.; Warren, C.R.; Adams, M.A. Dynamic light use and protection from excess light in upper canopy and coppice leaves of Nothofagus cunninghamii in an old growth, cool temperate rainforest in Victoria, Australia. New Phytol. 2005, 165, 143–156.

- Leakey, A.; Press, M.C.; Scholes, J.D. Patterns of dynamic irradiance affect the photosynthetic capacity and growth of dipterocarp tree seedlings. Oecologia 2003, 135, 184–193.

- Sims, D.A.; Pearcy, R.W. Sunfleck frequency and duration affects growth rate of the understorey plant, Alocasia macrorrhiza. Funct. Ecol. 1993, 7, 683–689.

- Rijkers, T.; De Vries, P.J.; Pons, T.L.; Bongers, F. Photosynthetic induction in saplings of three shade-tolerant tree species: Comparing understorey and gap habitats in a French Guiana rain forest. Oecologia 2000, 125, 331–340.

- Qiao, M.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Liu, L.A.; Shi, L.; Ma, Q.H.; Chow, W.S.; Jiang, C.D. Do rapid photosynthetic responses protect maize leaves against photoinhibition under fluctuating light? Photosynth. Res. 2021, 149, 57–68.

- Tang, Y.H.; Koizumi, H.; Satoh, M.; Washitani, I. Characteristics of transient photosynthesis in Quercus serrata seedlings grown under lightfleck and constant light regimes. Oecologia 1994, 100, 463–469.

- Matthews, J.S.; Vialet-Chabrand, S.; Lawson, T. Acclimation to fluctuating light impacts the rapidity of response and diurnal rhythm of stomatal conductance. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 1939–1951.

- Zhang, Y.; Kaiser, E.; Marcelis, L.F.; Yang, Q.; Li, T. Salt stress and fluctuating light have separate effects on photosynthetic acclimation, but interactively affect biomass. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 2192–2206.

- Poorter, L.; Oberbauer, S.F. Photosynthetic induction responses of two rainforest tree species in relation to light environment. Oecologia 1993, 96, 193–199.

- Han, Q.; Yamaguchi, E.; Odaka, N.; Kakubari, Y. Photosynthetic induction responses to variable light under field conditions in three species grown in the gap and understory of a Fagus crenata forest. Tree Physiol. 1999, 19, 625–634.

- Wong, S.L.; Chen, C.W.; Huang, H.W.; Weng, J.H. Using combined measurements for comparison of light induction of stomatal conductance, electron transport rate and CO2 fixation in woody and fern species adapted to different light regimes. Tree Physiol. 2012, 32, 535–544.

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Q.; Tabassum, M.A.; Ye, M.; Peng, S.; Li, Y. The inhibition of photosynthesis under water deficit conditions is more severe in flecked than uniform irradiance in rice (Oryza sativa) plants. Funct. Plant Biol. 2017, 44, 464–472.

- Sakoda, K.; Taniyoshi, K.; Yamori, W.; Tanaka, Y. Drought stress reduces crop carbon gain due to delayed photosynthetic induction under fluctuating light conditions. Physiol. Plantarum 2022, 174, e13603.

- Sun, H.; Shi, Q.; Liu, N.Y.; Zhang, S.B.; Huang, W. Drought stress delays photosynthetic induction and accelerates photoinhibition under short-term fluctuating light in tomato. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2023, 196, 152–161.

- Zhang, Y.; Kaiser, E.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, T. Short-term salt stress strongly affects dynamic photosynthesis, but not steady-state photosynthesis, in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 149, 109–119.

- Leakey, A.D.B.; Press, M.C.; Scholes, J.D. High-temperature inhibition of photosynthesis is greater under sunflecks than uniform irradiance in a tropical rain forest tree seedling. Plant Cell Environ. 2003, 26, 1681–1690.

- Huang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, X.; Peng, S.; Li, Y. Nitrogen can alleviate the inhibition of photosynthesis caused by high temperature stress under both steady-state and flecked irradiance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 945.

- Yamori, W.; Masumoto, C.; Fukayama, H.; Makino, A. Rubisco activase is a key regulator of non-steady-state photosynthesis at any leaf temperature and, to a lesser extent, of steady-state photosynthesis at high temperature. Plant J. 2012, 71, 871–880.

- Kang, H.X.; Zhu, X.G.; Yamori, W.; Tang, Y.H. Concurrent increases in leaf temperature with light accelerate photosynthetic induction in tropical tree seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1216.

- Kaiser, E.; Kromdijk, J.; Harbinson, J.; Heuvelink, E.; Marcelis, L.F. Photosynthetic induction and its diffusional, carboxylation and electron transport processes as affected by CO2 partial pressure, temperature, air humidity and blue irradiance. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 191–205.

- Košvancová, M.; Urban, O.; Šprtová, M.; Hrstka, M.; Kalina, J.; Tomášková, I.; Špunda, V.; Marek, M.V. Photosynthetic induction in broadleaved Fagus sylvatica and coniferous Picea abies cultivated under ambient and elevated CO2 concentrations. Plant Sci. 2009, 177, 123–130.

- Tomimatsu, H.; Tang, Y. Elevated CO2 differentially affects photosynthetic induction response in two Populus species with different stomatal behavior. Oecologia 2012, 169, 869–878.

- Leakey, A.D.B.; Press, M.C.; Scholes, J.D.; Watling, J.R. Relative enhancement of photosynthesis and growth at elevated CO2 is greater under sunflecks than uniform irradiance in a tropical rain forest tree seedling. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 1701–1714.

- Tomimatsu, H.; Iio, A.; Adachi, M.; Saw, L.G.; Fletcher, C.; Tang, Y. High CO2 concentration increases relative leaf carbon gain under dynamic light in Dipterocarpus sublamellatus seedlings in a tropical rain forest, Malaysia. Tree Physiol. 2014, 34, 944–954.

- Kaiser, E.; Zhou, D.; Heuvelink, E.; Harbinson, J.; Morales, A.; Marcelis, L.F. Elevated CO2 increases photosynthesis in fluctuating irradiance regardless of photosynthetic induction state. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 5629–5640.

- Kang, H.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ke, X.; Sun, W.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Shen, H.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y. Elevated CO2 enhances dynamic photosynthesis in rice and wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 727374.

- Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, S.B.; Huang, W. Photosynthetic induction under fluctuating light is affected by leaf nitrogen content in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 835571.

- Chen, J.W.; Yang, Z.Q.; Zhou, P.; Hai, M.R.; Tang, T.X.; Liang, Y.L.; An, T.X. Biomass accumulation and partitioning, photosynthesis, and photosynthetic induction in field-grown maize (Zea mays L.) under low-and high-nitrogen conditions. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013, 35, 95–105.

- Sun, J.; Ye, M.; Peng, S.; Li, Y. Nitrogen can improve the rapid response of photosynthesis to changing irradiance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) plants. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31305.

- Li, Y.T.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.N.; Liang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, G.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Z.S.; Gao, H.Y. Dynamic light caused less photosynthetic suppression, rather than more, under nitrogen deficit conditions than under sufficient nitrogen supply conditions in soybean. BMC Plant Bio. 2020, 20, 339.

- Saito, A.; Iino, T.; Sonoike, K.; Miwa, E.; Higuchi, K. Remodeling of the major light-harvesting antenna protein of PSII protects the young leaves of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) from photoinhibition under prolonged iron deficiency. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 2013–2030.

- Singh, S.K.; Reddy, V.R. Methods of mesophyll conductance estimation: Its impact on key biochemical parameters and photosynthetic limitations in phosphorus-stressed soybean across CO2. Physiol. Plantarum 2016, 157, 234–254.

- Hu, W.; Lu, Z.; Meng, F.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Ren, T.; Sharkey, T.D.; Lu, J. The reduction in leaf area precedes that in photosynthesis under potassium deficiency: The importance of leaf anatomy. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 1749–1763.

- Allen, M.T.; Pearcy, R.W. Stomatal behavior and photosynthetic performance under dynamic light regimes in a seasonally dry tropical rain forest. Oecologia 2000, 122, 470–478.

- Allen, M.T.; Pearcy, R.W. Stomatal versus biochemical limitations to dynamic photosynthetic performance in four tropical rainforest shrub species. Oecologia 2000, 122, 479–486.

- Pearcy, R.W.; Osteryoung, K.; Calkin, H.W. Photosynthetic responses to dynamic light environments by Hawaiian trees: Time course of CO2 uptake and carbon gain during sunflecks. Plant Physiol. 1985, 79, 896–902.

- Krall, J.P.; Pearcy, R.W. Concurrent measurements of oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange during lightflecks in maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Physiol. 1993, 103, 823–828.

- Kirschbaum, M.U.F.; Pearcy, R.W. Concurrent measurements of oxygen-and carbondioxide exchange during light flecks in Alocasia macrorrhiza (L.) G. Don. Planta 1988, 174, 527–533.

- Pons, T.L.; Pearcy, R.W. Photosynthesis in flashing light in soybean leaves grown in different conditions. II. Lightfleck utilization efficiency. Plant Cell Environ. 1992, 15, 577–584.

- Kubásek, J.; Urban, O.; Šantrůček, J. C4 plants use fluctuating light less efficiently than do C3 plants: A study of growth, photosynthesis and carbon isotope discrimination. Physiol. Plantarum 2013, 149, 528–539.

- Li, Y.T.; Luo, J.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Z.S. C4 species utilize fluctuating light less efficiently than C3 species. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1288–1291.

- Lee, M.S.; Boyd, R.A.; Ort, D.R. The photosynthetic response of C3 and C4 bioenergy grass species to fluctuating light. Gcb Bioenergy 2022, 14, 37–53.

- Cubas, L.A.; Vath, R.L.; Bernardo, E.L.; Sales, C.R.G.; Burnett, A.C.; Kromdijk, J. Activation of CO2 assimilation during photosynthetic induction is slower in C4 than in C3 photosynthesis in three phylogenetically controlled experiments. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1091115.

- Slattery, R.A.; Walker, B.J.; Weber, A.P.; Ort, D.R. The impacts of fluctuating light on crop performance. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 990–1003.

- Covshoff, S.; Hibberd, J.M. Integrating C4 photosynthesis into C3 crops to increase yield potential. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2012, 23, 209–214.

- Schuler, M.L.; Mantegazza, O.; Weber, A.P. Engineering C4 photosynthesis into C3 chassis in the synthetic biology age. Plant J. 2016, 87, 51–65.

- Ermakova, M.; Danila, F.R.; Furbank, R.T.; von Caemmerer, S. On the road to C4 rice: Advances and perspectives. Plant J. 2020, 101, 940–950.

- Valladares, F.; Allen, M.T.; Pearcy, R.W. Photosynthetic responses to dynamic light under field conditions in six tropical rainforest shrubs occuring along a light gradient. Oecologia 1997, 111, 505–514.

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.J.; Song, L.Y.; Liu, N.; Sun, L.L.; Peng, C.L. Utilization of lightflecks by seedlings of five dominant tree species of different subtropical forest successional stages under low-light growth conditions. Tree Physiol. 2012, 32, 545–553.

- Deans, R.M.; Brodribb, T.J.; Busch, F.A.; Farquhar, G.D. Plant water-use strategy mediates stomatal effects on the light induction of photosynthesis. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 382–395.

- Adachi, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Miyagi, A.; Kashima, M.; Tezuka, A.; Toya, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Ohkubo, S.; Shimizu, H.; Kawai-Yamada, M.; et al. High-yielding rice Takanari has superior photosynthetic response to a commercial rice Koshihikari under fluctuating light. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 5287–5297.

- Acevedo-Siaca, L.G.; Coe, R.; Wang, Y.; Kromdijk, J.; Quick, W.P.; Long, S.P. Variation in photosynthetic induction between rice accessions and its potential for improving productivity. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 1097–1108.

- Acevedo-Siaca, L.G.; Dionora, J.; Laza, R.; Quick, W.P.; Long, S.P. Dynamics of photosynthetic induction and relaxation within the canopy of rice and two wild relatives. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, e286.

- Acevedo-Siaca, L.G.; Coe, R.; Quick, W.P.; Long, S.P. Variation between rice accessions in photosynthetic induction in flag leaves and underlying mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 1282–1294.

- Cowling, S.B.; Treeintong, P.; Ferguson, J.; Soltani, H.; Swarup, R.; Mayes, S.; Murchie, E.H. Out of Africa: Characterizing the natural variation in dynamic photosynthetic traits in a diverse population of African rice (Oryza glaberrima). J Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3283–3298.

- Salter, W.T.; Merchant, A.M.; Richards, R.A.; Trethowan, R.; Buckley, T.N. Rate of photosynthetic induction in fluctuating light varies widely among genotypes of wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 2787–2796.

- Soleh, M.A.; Tanaka, Y.; Nomoto, Y.; Iwahashi, Y.; Nakashima, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Long, S.P.; Shiraiwa, T. Factors underlying genotypic differences in the induction of photosynthesis in soybean . Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 685–693.

- Soleh, M.A.; Tanaka, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Huber, S.C.; Sakoda, K.; Shiraiwa, T. Identification of large variation in the photosynthetic induction response among 37 soybean genotypes that is not correlated with steady-state photosynthetic capacity. Photosynth. Res. 2017, 131, 305–315.

- Eyland, D.; van Wesemael, J.; Lawson, T.; Carpentier, S. The impact of slow stomatal kinetics on photosynthesis and water use efficiency under fluctuating light. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 998–1012.

- De Souza, A.P.; Wang, Y.; Orr, D.J.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Long, S.P. Photosynthesis across African cassava germplasm is limited by Rubisco and mesophyll conductance at steady state, but by stomatal conductance in fluctuating light. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 2498–2512.

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Estavillo, G.M.; Luo, T.; Hu, L. Leaf N content regulates the speed of photosynthetic induction under fluctuating light among canola genotypes (Brassica napus L.). Physiol. Plantarum 2021, 172, 1844–1852.

- Wang, X.Q.; Zeng, Z.L.; Shi, Z.M.; Wang, J.H.; Huang, W. Variation in photosynthetic efficiency under fluctuating light between rose cultivars and its potential for improving dynamic photosynthesis. Plants 2023, 12, 1186.

- Xiong, Z.; Xiong, D.; Cai, D.; Wang, W.; Cui, K.; Peng, S.; Huang, J. Effect of stomatal morphology on leaf photosynthetic induction under fluctuating light across diploid and tetraploid rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 194, 104757.

- Vialet-Chabrand, S.R.; Matthews, J.S.; McAusland, L.; Blatt, M.R.; Griffiths, H.; Lawson, T. Temporal dynamics of stomatal behavior: Modeling and implications for photosynthesis and water use. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 603–613.

- McAusland, L.; Vialet-Chabrand, S.; Davey, P.; Baker, N.R.; Brendel, O.; Lawson, T. Effects of kinetics of light-induced stomatal responses on photosynthesis and water-use efficiency. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1209–1220.

- Kirschbaum, M.F.; Pearcy, R. Gas exchange analysis of the relative importance of stomatal and biochemical factors in photosynthetic induction in Alocasiamacrorrhiza. Plant Physiol. 1988, 86, 782–785.

- Ogren, E.; Sundin, U. Photosynthetic responses to variable light: A comparison of species from contrasting habitats. Oecologia 1996, 106, 18–27.

- Auchincloss, L.; Easlon, H.M.; Levine, D.; Donovan, L.; Richards, J.H. Pre-dawn stomatal opening does not substantially enhance early-morning photosynthesis in Helianthus annuus. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1364–1370.

- Kardiman, R.; Ræbild, A. Relationship between stomatal density, size and speed of opening in Sumatran rainforest species. Tree physiol. 2018, 38, 696–705.

- Xiong, Z.; Dun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Xiong, D.; Cui, K.; Peng, S.; Huang, J. Effect of stomatal morphology on leaf photosynthetic induction under fluctuating light in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 754790.

- Qu, M.; Essemine, J.; Xu, J.; Ablat, G.; Perveen, S.; Wang, H.; Chen, K.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, G.; Chu, C.; et al. Alterations in stomatal response to fluctuating light increase biomass and yield of rice under drought conditions. Plant J. 2020, 104, 1334–1347.

- Kaiser, E.; Morales, A.; Harbinson, J.; Heuvelink, E.; Marcelis, L.F. High stomatal conductance in the tomato Flacca mutant allows for faster photosynthetic induction. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1317.

- Sakoda, K.; Yamori, W.; Shimada, T.; Sugano, S.S.; Hara-Nishimura, I.; Tanaka, Y. Higher stomatal density improves photosynthetic induction and biomass production in Arabidopsis under fluctuating light. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 589603.

- Yamori, W.; Kusumi, K.; Iba, K.; Terashima, I. Increased stomatal conductance induces rapid changes to photosynthetic rate in response to naturally fluctuating light conditions in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 1230–1240.

- Kimura, H.; Hashimoto-Sugimoto, M.; Iba, K.; Terashima, I.; Yamori, W. Improved stomatal opening enhances photosynthetic rate and biomass production in fluctuating light. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 2339–2350.

- Papanatsiou, M.; Petersen, J.; Henderson, L.; Wang, Y.; Christie, J.M.; Blatt, M.R. Optogenetic manipulation of stomatal kinetics improves carbon assimilation, water use, and growth. Science 2019, 363, 1456–1459.

- Ruban, A.V. Nonphotochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching: Mechanism and effectiveness in protecting plants from photodamage. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 1903–1916.

- Zhu, X.G.; Ort, D.R.; Whitmarsh, J.; Long, S.P. The slow reversibility of photosystem II thermal energy dissipation on transfer from high to low light may cause large losses in carbon gain by crop canopies: A theoretical analysis. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1167–1175.

- Kono, M.; Terashima, I. Long-term and short-term responses of the photosynthetic electron transport to fluctuating light. J. Photoch. Photobio. B 2014, 137, 89–99.

- Hubbart, S.; Ajigboye, O.O.; Horton, P.; Murchie, E.H. The photoprotective protein PsbS exerts control over CO2 assimilation rate in fluctuating light in rice. Plant J. 2012, 71, 402–412.

- Kromdijk, J.; Głowacka, K.; Leonelli, L.; Gabilly, S.T.; Iwai, M.; Niyogi, K.K.; Long, S.P. Improving photosynthesis and crop productivity by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science 2016, 354, 857–861.

- De Souza, A.P.; Burgess, S.J.; Doran, L.; Hansen, J.; Manukyan, L.; Maryn, N.; Gotarkar, D.; Leonelli, L.; Niyogi, K.K.; Long, S.P. Soybean photosynthesis and crop yield are improved by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science 2022, 377, 851–854.

- Garcia-Molina, A.; Leister, D. Accelerated relaxation of photoprotection impairs biomass accumulation in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 9–12.

- Lehretz, G.G.; Schneider, A.; Leister, D.; Sonnewald, U. High non-photochemical quenching of VPZ transgenic potato plants limits CO2 assimilation under high light conditions and reduces tuber yield under fluctuating light. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 1821–1832.

- Basso, L.; Sakoda, K.; Kobayashi, R.; Yamori, W.; Shikanai, T. Flavodiiron proteins enhance the rate of CO2 assimilation in Arabidopsis under fluctuating light intensity. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 375–387.

- Uflewski, M.; Mielke, S.; Correa Galvis, V.; von Bismarck, T.; Chen, X.; Tietz, E.; Ruß, J.; Luzarowski, M.; Sokolowska, E.; Skirycz, A.; et al. Functional characterization of proton antiport regulation in the thylakoid membrane. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 2209–2229.

- Carmo-Silva, A.E.; Salvucci, M.E. The regulatory properties of Rubisco activase differ among species and affect photosynthetic induction during light transitions. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 1645–1655.

- Kim, S.Y.; Harvey, C.M.; Giese, J.; Lassowskat, I.; Singh, V.; Cavanagh, A.P.; Spalding, M.H.; Finkemeier, I.; Ort, D.R.; Huber, S.C. In vivo evidence for a regulatory role of phosphorylation of Arabidopsis Rubisco activase at the Thr78 site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 18723–18731.

- McCormick, A.J.; Kruger, N.J. Lack of fructose 2, 6-bisphosphate compromises photosynthesis and growth in Arabidopsis in fluctuating environments. Plant J. 2015, 81, 670–683.

- Om, K.; Arias, N.N.; Jambor, C.C.; MacGregor, A.; Rezachek, A.N.; Haugrud, C.; Kunz, H.H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, P.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Pyruvate, phosphate dikinase regulatory protein impacts light response of C4 photosynthesis in Setaria viridis. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 1117–1133.

- Salvatori, N.; Carteni, F.; Giannino, F.; Alberti, G.; Mazzoleni, S.; Peressotti, A.A. system dynamics approach to model photosynthesis at leaf level under fluctuating light. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 3368.

- Ferroni, L.; Živčak, M.; Sytar, O.; Kovár, M.; Watanabe, N.; Pancaldi, S.; Baldisserotto, C.; Brestič, M. Chlorophyll-depleted wheat mutants are disturbed in photosynthetic electron flow regulation but can retain an acclimation ability to a fluctuating light regime. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 178, 104156.

More

Information

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.4K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

05 Jun 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No