| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parveen Kumar | -- | 2213 | 2023-05-25 08:57:29 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 3 word(s) | 2216 | 2023-05-25 10:11:12 | | |

Video Upload Options

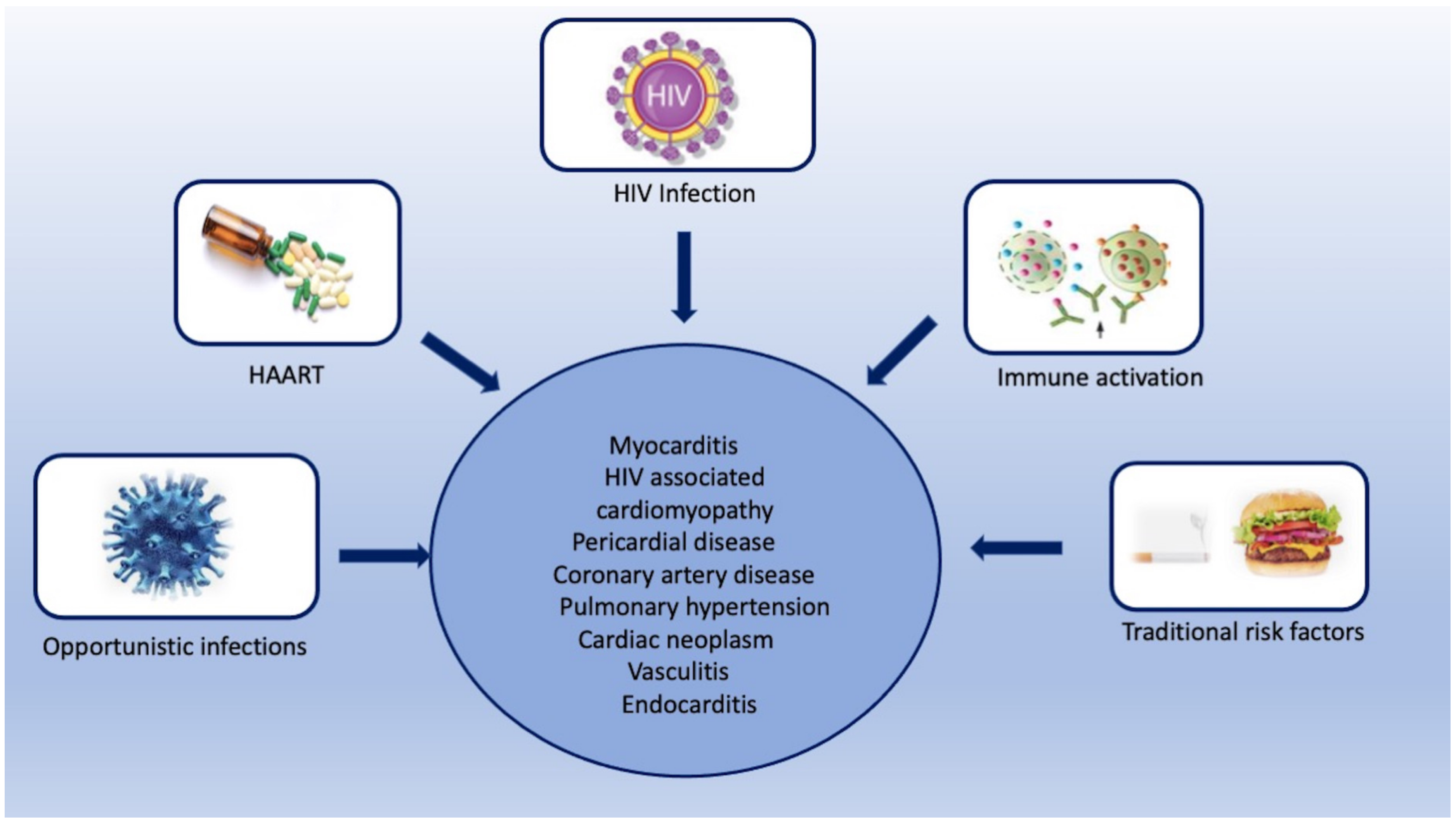

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. The introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has significantly reduced the risk of developing acquired immune deficiency syndrome and increased life expectancy, approaching that of the general population. However, people living with HIV have a substantially increased risk of cardiovascular diseases despite long-term viral suppression using ART. HIV-associated cardiovascular complications encompass a broad spectrum of diseases that involve the myocardium, pericardium, coronary arteries, valves, and systemic and pulmonary vasculature. Traditional risk stratification tools do not accurately predict cardiovascular risk in this population. Multimodality imaging plays an essential role in the evaluation of various HIV-related cardiovascular complications.

1. Introduction

2. HIV-Associated Cardiovascular Complications

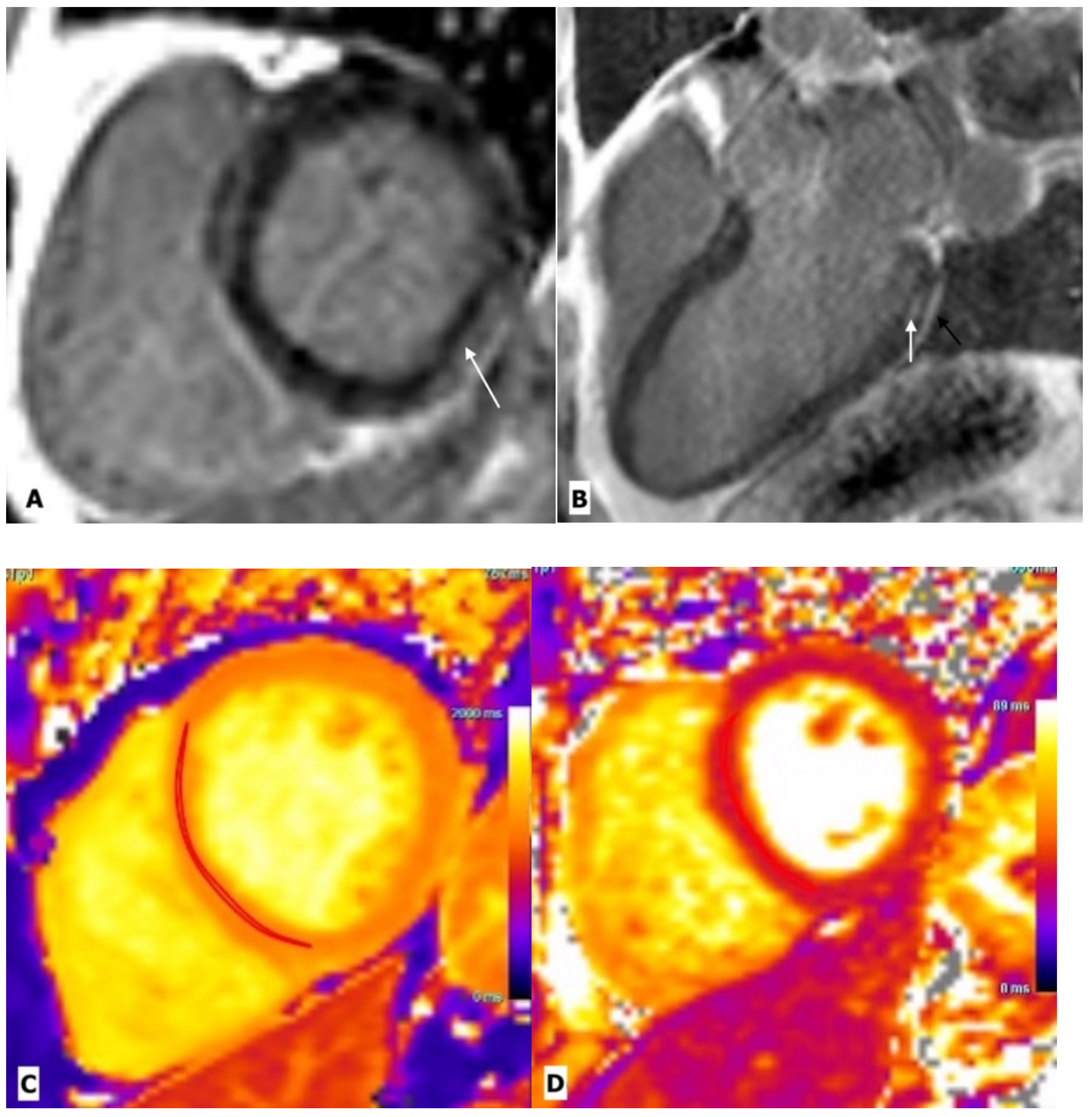

2.1. Myocarditis

2.2. HIV Associated Cardiomyopathy

2.3. Pericardial Diseases

2.4. Coronary Artery Diseases

2.5. Pulmonary Hypertension

2.6. Cardiac Neoplasm

2.7. Vasculitis

2.8. Endocarditis

3. Conclusions

References

- Mocroft, A.; Ledergerber, B.; Katlama, C.; Kirk, O.; Reiss, P.; d’Arminio Monforte, A.; Knysz, B.; Dietrich, M.; Phillips, A.; Lundgren, J. Decline in the AIDS and Death Rates in the EuroSIDA Study: An Observational Study. Lancet 2003, 362, 22–29.

- Hemkens, L.G.; Bucher, H.C. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 1373–1381.

- Triant, V.A.; Lee, H.; Hadigan, C.; Grinspoon, S.K. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 2506–2512.

- Duprez, D.; Neuhaus, J.; Kuller, L.; Tracy, R.; Belloso, W.; De Wit, S. Inflammation, Coagulation and Cardiovascular Disease in HIV-Infected Individuals. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44454.

- Remick, J.; Georgiopoulou, V.; Marti, C.; Ofotokun, I.; Kalogeropoulos, A.; Lewis, W.; Butler, J. Heart Failure in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Future Research. Circulation 2014, 129, 1781–1789.

- Erqou, S.; Lodebo, B.T.; Masri, A.; Altibi, A.M.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Dzudie, A.; Ataklte, F.; Choudhary, G.; Bloomfield, G.S.; Wu, W.-C.; et al. Cardiac Dysfunction among People Living with HIV. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 98–108.

- Post, W.S.; Budoff, M.; Kingsley, L.; Palella, F.J., Jr.; Witt, M.D.; Li, X.; George, R.T.; Brown, T.T.; Jacobson, L.P. Associations between HIV infection and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 458–467.

- Sood, V.; Jermy, S.; Saad, H.; Samuels, P.; Moosa, S.; Ntusi, N. Review of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in human immunodeficiency virus-associated cardiovascular disease. SA J. Radiol. 2017, 21, 1248.

- Herskowitz, A.; Wu, T.-C.; Willoughby, S.B.; Vlahov, D.; Ansari, A.A.; Beschorner, W.E.; Baughman, K.L. Mycarditis and Cardiotropic Viral Infection Associated with Severe Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Late-Stage Infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994, 24, 1025–1032.

- Barbaro, G.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Grisorio, B.; Barbarini, G.; the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio Cardiologico dei Pazienti Affetti da AIDS Investigators. Cardiac involvement in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: A multicenter clinical-pathological study. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1998, 14, 1071–1077.

- Barbaro, G. Cardiovascular manifestations of HIV infection. J. R. Soc. Med. 2001, 94, 384–390.

- Adair, O.V.; Randive, N.; Krasnow, N. Isolated toxoplasma myocarditis in acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am. Heart J. 1989, 118, 856–857.

- Kinney, E.; Monsuez, J.; Kitzis, M.; Vittecoq, D. Treatment of AIDS-associated heart disease. Angiology 1989, 40, 970–976.

- Hofman, P.; Drici, M.D.; Gibelin, P.; Michiels, J.F.; Thyss, A. Prevalence of toxoplasma myocarditis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Br. Heart J. 1993, 70, 376–381.

- Twu, C.; Liu, N.Q.; Popik, W.; Bukrinsky, M.; Sayre, J.; Roberts, J.; Rania, S.; Bramhandam, V.; Roos, K.P.; MacLellan, W.R.; et al. Cardiomyocytes Undergo Apoptosis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Cardiomyopathy through Mitochondrion- and Death Receptor-Controlled Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14386–14391.

- Fiala, M.; Popik, W.; Qiao, J.; Lossinsky, A.; Alce, T.; Tran, K. HIV-1 induces cardiomyopathyby cardiomyocyte invasion and gp120, tat, and cytokine apoptotic signaling. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2004, 4, 097–108.

- Barbaro, G. HIV-associated cardiomyopathy. Herz. Kardiovask. Erkrank. 2005, 30, 486–492.

- Duan, M.; Yao, H.; Hu, G.; Chen, X.; Lund, A.K.; Buch, S. HIV Tat induces expression of ICAM-1 in HUVECs: Implications for miR-221/-222 in HIV-associated cardiomyopathy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60170.

- Olusegun-Joseph, D.A.; Ajuluchukwu, J.N.; Okany, C.C.; Mbakwem, A.C.; Oke, D.A.; Okubadejo, N.U. Echocardiographic patterns in treatment-naïve HIV-positive patients in Lagos, south-west Nigeria. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2012, 23, e1–e6.

- Luetkens, J.A.; Doerner, J.; Schwarze-Zander, C.; Wasmuth, J.-C.; Boesecke, C.; Sprinkart, A.M.; Schmeel, F.C.; Homsi, R.; Gieseke, J.; Schild, H.H.; et al. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Reveals Signs of Subclinical Myocardial Inflammation in Asymptomatic HIV-Infected Patients. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e004091.

- Ntusi, N.A.; O’Dwyer, E.; Dorrell, L.; Piechnik, S.K.; Ferreira, V.M.; Karamitsos, T.D.; Sam, E.; Clarke, K.; Neubauer, S.; Holloway, C. HIV-1-Related Cardiovascular Disease Is Associated with Chronic Inflammation, Frequent Pericardial Effusions and Increased Myocardial Oedema. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Resonan. 2016, 18, O104.

- Hsue, P.Y.; Hunt, P.W.; Ho, J.E.; Farah, H.H.; Schnell, A.; Hoh, R.; Martin, J.N.; Deeks, S.G.; Bolger, A.F. Impact of HIV Infection on Diastolic Function and Left Ventricular Mass. Circ. Heart Fail. 2010, 3, 132–139.

- Mendes, L.; Silva, D.; Miranda, C.; Sá, J.; Duque, L.; Duarte, N.; Brito, P.; Bernardino, L.; Poças, J. Impact of HIV Infection on Cardiac Deformation. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2014, 33, 501–509.

- Barbaro, G.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Grisorio, B.; Barbarini, G. Incidence of dilated cardiomyopathy and detection of HIV in myocardial cells of HIV-positive patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1093–1099.

- Levy, W.S.; Simon, G.L.; Rios, J.C.; Ross, A.M. Prevalence of cardiac abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am. J. Cardiol. 1989, 63, 86–89.

- Himelman, R.B.; Chung, W.S.; Chernoff, D.N.; Schiller, N.B.; Hollander, H. Cardiac manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection: A two-dimensional echocardiographic study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1989, 13, 1030–1036.

- Lumsden, R.H.; Bloomfield, G.S. The Causes of HIV-Associated Cardiomyopathy: A Tale of Two Worlds. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1–9.

- Currie, P.F.; Jacob, A.J.; Foreman, A.R.; Elton, R.A.; Brettle, R.P.; Boon, N.A. Heart muscle disease related to HIV infection: Prognostic implications. BMJ 1994, 309, 1605–1607.

- D’Amati, G.; di Gioia, C.R.; Gallo, P. Pathological findings of HIV-associated cardiovascular disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 946, 23–45.

- Sliwa, K.; Carrington, M.J.; Becker, A.; Thienemann, F.; Ntsekhe, M.; Stewart, S. Contribution of the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome epidemic to de novo presentations of heart disease in the Heart of Soweto Study cohort. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 866–874.

- Simon, M.A.; Lacomis, C.D.; George, M.P.; Kessinger, C.; Weinman, R.; McMahon, D.; Gladwin, M.T.; Champion, H.C.; Morris, A. Isolated Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Short Title: Right Ventricular Dysfunction in HIV. J. Card. Fail. 2014, 20, 414–421.

- Hecht, S.R.; Berger, M.; Van Tosh, A.; Croxson, S. Unsuspected cardiac abnormalities in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Echocardiogr. Study Chest 1989, 96, 805–808.

- Akhras, F.; Dubrey, S.; Gazzard, B.; Noble, M.I. Emerging patterns of heart disease in HIV infected homosexual subjects with and without opportunistic infections; a prospective colour flow doppler echocardiographic study. Eur. Heart J. 1994, 15, 68–75.

- Madhyastha, P.S.; Reddy, C.; Shetty, G.; Shastry, B.; Doddamani, A. A study of pericardial effusion in HIV positive patients and its correlation with the CD4 count. Gulhane Med. J. 2021, 63, 20–24.

- Ntsekhe, M.; Mayosi, B.M. Tuberculous pericarditis with and without HIV. Heart Fail. Rev. 2013, 18, 367–373.

- Reuter, H.; Burgess, L.J.; Doubell, A.F. Epidemiology of pericardial effusions at a large academic hospital in South Africa. Epidemiol. Infect. 2005, 133, 393–399.

- Gowda, R.M.; Khan, I.A.; Mehta, N.J.; Gowda, M.R.; Sacchi, T.J.; Vasavada, B.C. Cardiac tamponade in patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. Angiology 2003, 54, 469–474.

- Boulanger, E.; Gérard, L.; Gabarre, J.; Molina, J.-M.; Rapp, C.; Abino, J.-F.; Cadranel, J.; Chevret, S.; Oksenhendler, E. Prognostic Factors and Outcome of Human Herpesvirus 8–Associated Primary Effusion Lymphoma in Patients with AIDS. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 4372–4380.

- Wilkes, J.D.; Fidias, P.; Vaickus, L.; Perez, R.P. Malignancy related pericardial effusion. 127 cases from the Roswell Park Cancer Institute. Cancer 1995, 76, 1377–1387.

- Paisible, A.-L.; Chang, C.-C.H.; So-Armah, K.A.; Butt, A.A.; Leaf, D.A.; Budoff, M.; Rimland, D.; Bedimo, R.; Goetz, M.B.; Rodriguez-Barradas, M.C.; et al. HIV Infection, Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factor Profile, and Risk for Acute Myocardial Infarction. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015, 68, 209–216.

- Krishnaswamy, G.; Chi, D.S.; Kelley, J.L.; Sarubbi, F.; Smith, J.K.; Peiris, A. The cardiovascular and metabolic complications of HIV infection. Cardiol. Rev. 2000, 8, 260–268.

- Ssinabulya, I.; Kayima, J.; Longenecker, C.; Luwedde, M.; Semitala, F.; Kambugu, A.; Ameda, F.; Bugeza, S.; McComsey, G.; Freers, J.; et al. Subclinical Atherosclerosis among HIV-Infected Adults Attending HIV/AIDS Care at Two Large Ambulatory HIV Clinics in Uganda. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89537.

- Bavinger, C.; Bendavid, E.; Niehaus, K.; Olshen, R.A.; Olkin, I.; Sundaram, V.; Wein, N.; Holodniy, M.; Hou, N.; Owens, D.K.; et al. Risk of Cardiovascular Disease from Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59551.

- Hecht, H.S. Coronary artery calcium scanning: Past, present, and future. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, 579–596.

- Raggi, P.; Zona, S.; Scaglioni, R.; Stentarelli, C.; Ligabue, G.; Besutti, G.; Menozzi, M.; Santoro, A.; Malagoli, A.; Bellasi, A.; et al. Epicardial Adipose Tissue and Coronary Artery Calcium Predict Incident Myocardial Infarction and Death in HIV-Infected Patients. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2015, 9, 553–558.

- Choi, E.-K.; Choi, S.I.; Rivera, J.J.; Nasir, K.; Chang, S.-A.; Chun, E.J.; Kim, H.-K.; Choi, D.-J.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Chang, H.-J. Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography as a Screening Tool for the Detection of Occult Coronary Artery Disease in Asymptomatic Individuals. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 357–365.

- Motoyama, S.; Sarai, M.; Harigaya, H.; Anno, H.; Inoue, K.; Hara, T.; Naruse, H.; Ishii, J.; Hishida, H.; Wong, N.D.; et al. Computed Tomographic Angiography Characteristics of Atherosclerotic Plaques Subsequently Resulting in Acute Coronary Syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 49–57.

- Opravil, M.; Sereni, D. Natural history of HIV-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: Trends in the HAART era. AIDS 2008, 22, S35–S40.

- Butrous, G. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2015, 131, 1361–1370.

- Mesa, R.A.; Edell, E.S.; Dunn, W.F.; Edwards, W.D. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and pulmonary hypertension: Two new cases and a review of 86 reported cases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1998, 73, 37–45.

- Mehta, N.J.; Khan, I.A.; Mehta, R.N.; Sepkowitz, D.A. HIV-related pulmonary hypertension: Analytic review of 131 cases. Chest 2000, 118, 1133–1141.

- Galiè, N.; Humbert, M.; Vachiery, J.-L.; Gibbs, S.; Lang, I.; Torbicki, A.; Simonneau, G.; Peacock, A.; Vonk Noordegraaf, A.; Beghetti, M.; et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed By: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 67–119.

- Mbulaiteye, S.M.; Parkin, D.M.; Rabkin, C.S. Epidemiology of AIDS-related malignancies: An international perspective. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 17, 673–696.

- O’Connor, P.G.; Scadden, D.T. AIDS oncology. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2000, 14, 945–965.

- Autran, B. AIDS in a Haitian woman with cardiac Kaposi’s sarcoma and Whipple’s disease. Lancet 1983, 321, 767–768.

- Silver, M.A.; Macher, A.M.; Reichert, C.M.; Levens, D.L.; Parrillo, J.E.; Longo, D.L.; Roberts, W.C. Cardiac Involvement by Kaposi’s Sarcoma in Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Am. J. Cardiol. 1984, 53, 983–985.

- Lewis, W. AIDS: Cardiac findings from 115 autopsies. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1989, 32, 207–215.

- Weatherald, J.; Boucly, A.; Chemla, D.; Savale, L.; Peng, M.; Jevnikar, M.; Jaïs, X.; Taniguchi, Y.; O’Connell, C.; Parent, F.; et al. Prognostic Value of Follow-up Hemodynamic Variables after Initial Management in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circulation 2018, 137, 693–704.

- Holladay, A.O.; Siegel, R.J.; Schwartz, D.A. Cardiac malignant lymphoma in acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Cancer 1992, 70, 2203–2207.

- Goldfarb, A.; King, C.L.; Rosenzweig, B.P.; Feit, F.; Kamat, B.R.; Rumancik, W.M.; Kronzon, I. Cardiac Lymphoma in the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Am. Heart J. 1989, 118, 1340–1344.

- Constantino, A.; West, T.E.; Gupta, M.; Loghmanee, F. Primary cardiac lymphoma in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Cancer 1987, 60, 2801–2805.

- Ciancarella, P.; Fusco, A.; Citraro, D.; Sperandio, M.; Floris, R. Multimodality imaging evaluation of a primary cardiac lymphoma. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2017, 29, 128–135.

- Dorsay, T.A.; Ho, V.B.; Rovira, M.J.; Armstrong, M.A.; Brissette, M.D. Primary cardiac lymphoma: CT and MR findings. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1993, 17, 978–981.

- Brasselet, C.; Maes, D.; Tassan, S.; Beguinot, I.; Jamet, B.; Nazeyrollas, P.; Metz, D.; Elaerts, J. Extensive mycotic coronary aneurysm detected by echocardiography: Apropos of a case. Arch. Mal. Coeur. Vaiss. 1999, 92, 1229–1233. (In French)

- Gouny, P.; Valverde, A.; Vincent, D.; Fadel, E.; Lenot, B.; Tricot, J.F.; Rozenbaum, W.; Nussaume, O. Human immunodeficiency virus and infected aneurysm of the abdominal aorta: Report of three cases. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1992, 6, 239–243.

- Sellami, D.; Lucidarme, O.; Lebleu, L.; Grenier, P. Infected aneurysm of abdominal aorta: Early CT finding. J. Radiol. 2000, 81, 899–901. (In French)

- Chetty, R.; Batitang, S.; Nair, R. Large artery vasculopathy in HIV-positive patients: Another vasculitic enigma. Hum. Pathol. 2000, 31, 374–379.

- Marks, C.; Kuskov, S. Pattern of arterial aneurysms in acquired immunodeficiency disease. World J. Surg. 1995, 19, 127–132.

- Guillamon Toran, L.; Romeu Fontanillas, J.; Forcada Sainz, J.M.; Curos Abadal, A.; Larrousse Perez, E.; Valle Tudela, V. Heart pathology of extracardiac origin. I. Cardiac involvement in AIDS. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 1997, 50, 721–728.

- Nahass, R.G.; Weinstein, M.P.; Bartels, J.; Gocke, D.J. Infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users: A comparison of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-negative and -positive patients. J. Infect. Dis. 1990, 162, 967–970.

- Erba, P.A.; Pizzi, M.N.; Roque, A.; Salaun, E.; Lancellotti, P.; Tornos, P.; Habib, G. Multimodality Imaging in Infective Endocarditis. Circulation 2019, 140, 1753–1765.

- Bai, A.D.; Steinberg, M.; Showler, A.; Burry, L.; Bhatia, R.S.; Tomlinson, G.L.; Bell, C.M.; Morris, A.M. Diagnostic accuracy of transthoracic echocardiography for infective endocarditis findings using transesophageal echocardiography as the reference standard: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 639–646.e8.

- Sifaoui, I.; Oliver, L.; Tacher, V.; Fiore, A.; Lepeule, R.; Moussafeur, A.; Huguet, R.; Teiger, E.; Audureau, E.; Derbel, H.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Transesophageal Echocardiography and Cardiac Computed Tomography in Infective Endocarditis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2020, 33, 1442–1453.

- Huang, R.M.; Naidich, D.P.; Lubat, E.; Schinella, R.; Garay, S.M.; McCauley, D.I. Septic pulmonary emboli: CT-radiographic correlation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1989, 153, 41–45.

- Kuhlman, J.E.; Fishman, E.K.; Teigen, C. Pulmonary septic emboli: Diagnosis with CT. Radiology 1990, 174, 211–213.