Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Costas Constantinou | -- | 2595 | 2023-05-24 16:41:50 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 2595 | 2023-05-25 02:57:57 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Constantinou, C.S.; Nikitara, M. Core Cultural Competencies for Healthcare Professionals. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44788 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Constantinou CS, Nikitara M. Core Cultural Competencies for Healthcare Professionals. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44788. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Constantinou, Costas S., Monica Nikitara. "Core Cultural Competencies for Healthcare Professionals" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44788 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Constantinou, C.S., & Nikitara, M. (2023, May 24). Core Cultural Competencies for Healthcare Professionals. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/44788

Constantinou, Costas S. and Monica Nikitara. "Core Cultural Competencies for Healthcare Professionals." Encyclopedia. Web. 24 May, 2023.

Copy Citation

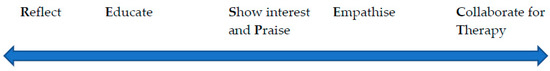

There are many guidelines regarding cultural competencies for healthcare professionals and many instruments aiming to measure cultural competence. However, there is no consensus on which core cultural competencies are necessary for healthcare professionals. A review of 15 Delphi studies showed that the core competencies necessary for healthcare professionals to ensure that they provide culturally congruent care were: Reflect, Educate, Show Interest and Praise, Empathise, and Collaborate for Therapy. These competencies make the abbreviation and word RESPECT, which symbolically places emphasis on respect as the overarching behaviour for working effectively with diversity.

cultural competence

diversity

Delphi study

healthcare

allied healthcare

1. Introduction

Cultural competence has been acknowledged as an important set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that can help tackle health disparities [1]. Although it has been defined many times, in general, cultural competence refers to knowledge of social and cultural factors that influence disease and illness experience and to any actions taken by the healthcare provider to ensure a high quality of care in relation to patients’ background [2]. There is research evidence that shows that cultural competence has contributed to the improvement of care for diverse populations. More specifically, there are a few systematic reviews involving studies from the 1980s to 2019. Price et al. [3] reviewed research from between 1980 and 2003 and discussed how cultural competence improved attitudes, skills, and patient satisfaction; one study showed a link between cultural competence and adherence to therapy. The review by Renzaho et al. [4] focused on studies published between 2000 and 2011 and revealed that training in cultural competence improved clinicians’ cultural awareness and sensitivity. Interestingly, later systematic reviews of evidence did not yield any different results. That is, Horvat et al.’s [5] review aimed to focus on randomised control trials in order to identify a causal relationship between cultural competence and health outcomes. Although they did not find a direct relationship between cultural competence and health outcomes, the study showed a clear improvement in adherence and understanding between patients and doctors. Alizadeth and Chavan’s [6] study reviewed research between 2000 and 2013 and found that patient satisfaction and adherence were enhanced when clinicians were culturally competent, but the researchers failed to find a clear link between cultural competence and positive health outcomes. Similarly, Vella, White, and Livingston [7] did not find a link between cultural competence and health outcomes, although patients’ perceptions of healthcare professionals’ cultural competence improved. However, more recent systematic reviews, which explored studies published until 2019, have shown a different picture in terms of cultural competence’s influence on outcomes. That is, Chae et al. [8] reviewed randomised controlled trials and found that 9 out of the 12 eligible studies showed improvement in professional educational outcomes, while 3 of these studies indicated improvement in patient outcomes. Skipworth’s [9] systematic review found a strong association between cultural competency and quality of care, with healthcare professionals who had higher levels of cultural competence providing even better care. It seems that studies agree that cultural competence contributes to the improvement of healthcare professionals’ knowledge and skills, patient satisfaction, and adherence to therapy, while there is some evidence that shows improvement in health outcomes. Such mixed results in terms of the link between cultural competence and health outcomes might largely be due to the scarcity of well-designed randomised control trials and possibly due to the difficulty of properly measuring cultural competence [10]. There are many models of cultural competence and suggested competencies in the literature. Therefore, it is essential to explore which are the core cultural competencies for healthcare professionals.

2. Core Cultural Competencies and Guidelines

A systematic review of Delphi studies revealed a variety of competencies, skills, and behaviours that have been suggested by 443 experts who have worked with cultural competence and diverse populations in 37 countries around the globe. Experts’ specialties ranged from medical doctors to nurses, public health workers, members of cultural groups, social scientists, educators, and decision-makers in organizations. Interestingly, these cultural competencies had striking similarities and were grouped or categorised in core competencies. This section presents in a more simplified fashion, along with brief supportive guidelines, five behaviours or competencies in order to achieve cultural competence in healthcare and contribute towards tackling health disparities. These competencies make the abbreviation RESPECT and are follows: Reflect, Educate, Show Interest and Praise, Empathise, and Collaborate for Therapy. RESPECT competencies do not aim to simplify the complexity of socio-cultural factors influencing health and illness. Instead, RESPECT competencies simplify the process of cultural competence for healthcare professionals but still capture the need for systematic training in the complexity of the issue. This is on par with Costa’s [11] discussion about the complexity of diversity in healthcare and how the matter is not only about diversity knowledge but also about diversity management. On this note, RESPECT competencies aim to equip healthcare professionals with a set of abilities to understand, manage and work effectively with complexity. To achieve this, RESPECT competencies should be demonstrated in a specific order and work as a protocol, as presented below.

2.1. Reflect

Reflection is an important and demanding competency that requires knowledge and practice. Healthcare professionals should have knowledge of their own social and cultural context and the idea that their beliefs, ideas, and practices, as well as sciences, are cultural products. Having such knowledge, healthcare professionals should engage with critical reflection on their own beliefs and practices by approaching them from a mental distance and considering the origin and functions of their beliefs and practices and how they are beneficial while also considering what could be enhanced or improved. This can be achieved initially by thinking of a cultural practice healthcare professionals exercise in their daily life and might use in medical practices too. For example, in many cultures, “touching wood” is both a belief and action people engage with without much thinking, and they do so in order to control their luck. On par with Wright Mills’ “Sociological Imagination” [12], such a cultural practice could be approached by anybody in a critical manner by imagining it as unfamiliar to them and starting to develop questions in order to understand it from different angles and within the wider socio-cultural context. Healthcare professionals could then approach all of their practices, including their professional work, in the same critical way. More specifically, healthcare professionals could approach western biomedicine from a critical perspective, as it is a cultural product rather than purely a result of objective science, and hence delve into biomedicine’s limitations. Healthcare professionals could be trained on how to critically self-reflect and be appraised on such behaviour periodically. It is important that the competency of self-reflection should come first because if healthcare professionals are not aware of their own social and cultural context and they cannot see its impact on their own behaviour, they may not be able to show the necessary interest to learn about the social and cultural contexts of their patients from either the literature or the patients themselves, show understanding of how culture can shape patients’ health understanding and behaviour, and work with their patients in a collaborative and open-minded manner.

2.2. Educate

“Educate” in this context means the healthcare professionals’ competence to continuously educate themselves in the social determinants of health and how the social and cultural context of their patients plays a crucial role in the way patients understand disease, illness, and therapies. Such a socio-cultural context should encompass an understanding of the intersectionality of how various social factors (e.g., socio-economic background, ethnicity, gender, age, etc.) intersect together, causing people to be vulnerable to ill health [11]. The education of healthcare professionals takes place in universities, largely in medical sociology and anthropology sessions, but healthcare professionals could educate themselves through life-long learning by attending social sciences conferences and reading research studies and books that present principles, theories, and research findings on social and cultural influences on health and illness experiences. In other words, healthcare professionals could engage with this knowledge and promote it to their colleagues and their students. However, it should be acknowledged that it is not always feasible for busy healthcare professionals to spend so much time learning the social and cultural aspects of health. On this note, healthcare institutions or individual professionals could collaborate with social scientists specialised in health and illness to provide trainings or prepare reports on the cultural characteristics of various groups in the communities where they practice healthcare. Social scientists could also be recruited by healthcare institutions to work as members of healthcare teams. Even with life-long learning, healthcare professionals will not be fully aware of the vast cultural beliefs and practices in societies. Therefore, they could also explore and learn from their patients, as discussed below.

2.3. Show Interest and Praise

Healthcare professionals with good knowledge of the social and cultural context of health and illness should be keen to know more, especially if their patients tell them something different from what they learned from the literature. Therefore, showing genuine interest in learning from patients and valuing or praising patients’ knowledge and views sends a clear message to patients that the healthcare professionals care and that everything the patients consider important it is important for the healthcare professional too. For example, if a patient with diabetes wishes to fast due to religious reasons, a healthcare professional should neither be judgmental of their patient’s preferences nor ignore such a cultural belief by focusing on the impact of fasting on diabetes control. A healthcare professional should give their patients time and show interest in learning from patients about the importance of fasting for the patients themselves and in patients’ cultures. In addition, healthcare professionals should praise patients for sharing their knowledge because it is useful for gaining a deeper understanding of what the best management plan should be. Then, working in partnership (see Section 2.5. Collaborate for Therapy) with patients to find the best management plan will be critical for achieving positive health outcomes. By valuing or praising patients’ beliefs and ideas, healthcare professionals value the patients’ cultures and identities. This can be achieved by careful listening, giving patients enough time, developing questions, picking up verbal and non-verbal cues, and valuing or praising what the patient has expressed. Showing interest and praise would cause the patient to feel respected and valued and more prone to collaborate with their healthcare provider. Importantly, this competence is the bridge between self-reflection and prior knowledge and showing empathy and collaboration.

2.4. Empathise

Empathy cannot be demonstrated on its own without the previous competencies and without giving time to the patient to narrate and express themselves. Empathy, as the skill of understanding patients’ feelings and concerns, is one of the key skills in clinical communication, and it has been linked with patient satisfaction, motivation, adherence, and patient outcomes [13]. In the context of cultural competence, empathy is not only about understanding patients’ feelings but also about recognising, acknowledging, and validating the patients’ beliefs and perspectives even when they are completely different from the scientific perspectives that healthcare professionals rely on. Using the same example of a patient with diabetes who wants to fast, a healthcare professional could demonstrate empathy indirectly by not being judgmental and by showing interest in and praising the patient (see Section 2.3. Show Interest and Praise). In addition, a healthcare professional could demonstrate empathy more directly by expressing words or phrases indicating that the patient has a rationale, which is appreciated. Understanding patients’ cultural beliefs and perspective is facilitated by healthcare professionals’ prior knowledge (see competence “Educate”), showing interest and giving value to the patient’s perspective (see competence “Sow interest and Praise”), and considering that healthcare professionals also have their own beliefs, which might not always be on par with science (see competence “Reflect”).

2.5. Collaborate for Therapy

It seems that collaboration is very important for achieving cultural congruent healthcare and therapy, but healthcare professionals should demonstrate all of the previous competencies first. For example, focusing on the medical perspective or giving scientific information prior to all other competencies might seem as though patients’ ideas, concerns, and experiences are being dismissed and, as a result, patients might be hesitant to disclose information or collaborate with the healthcare professional or participate in the management and therapy of their conditions. Therefore, all previous competencies would help establish trust, good rapport, good doctor–patient relationship, mutual understanding, and respect, which would facilitate collaboration. Specifically, a healthcare professional could approach a patient with diabetes who would like to fast for a period of time due to religious reasons by being humble and ready to self-reflect, having knowledge of the patient’s social and cultural context, having shown interest to learn from the patient, having valued the patient’s perspective, and having shown an understanding of the patient’s ideas, concerns, and beliefs. Such an approach would help a healthcare professional to establish good grounds to work with this patient in partnership through shared decision-making techniques. Shared decision-making has been well-integrated into clinical communication curricula [13], and it has been linked with patient-reported good health outcomes and quality indicators [14]. Therefore, the patient with diabetes who would like to fast would possibly be keener to work with a healthcare professional who was not judgmental and valued their beliefs and wishes, which were considered for establishing the best plan for controlling diabetes during a fasting period.

The five core competencies described above make the abbreviation RESPECT (see Figure 1), which is a real word to symbolically place emphasis on the essence of working effectively with diversity, which involves respecting and practically showing appreciation or admiration for patients as social and cultural beings. RESPECT can work as a protocol for the culturally competent healthcare professional, inform research in each of the core competencies or in all competencies together, help researchers formulate instruments to measure RESPECT, and inform trainings and curricular sessions in healthcare, healthcare education, and allied health sciences.

Figure 1. The RESPECT competencies pathway for culturally competent healthcare professionals.

2.6. Comprehensive Definition of Cultural Competence of Healthcare Professionals

Having organised and qualitatively analysed the competencies on which experts in Delphi studies have reached a consensus, researchers developed a new comprehensive definition that reflects the RESPECT competencies, and it can inform future studies, measuring instruments, and trainings. The researchers define cultural competence of healthcare professionals as:

“The set of abilities to continuously learn, appreciate, and reflect on the diverse social and cultural context of their own and their patients’ experiences of health and illness, value and show understanding of their patients’ behaviour, beliefs, ideas, and concerns influenced by culture and society, and work in partnership with their patients to provide culturally congruent care.”

2.7. Limitations

Although a Delphi study relies on a rather rigid methodology, the procedures of the Delphi studies included herein varied. For example, Ziegler, Michaëlis, and Sørensen [15] in round one requested for experts to individually suggest the necessary competencies and then asked to score them, while Chae et al. [16] formulated many statements, drawing information from the literature, and sent the list of these statements to the experts to score. Farokhzadian et al.’s [17] study was about formulating a training programme and then sending it to experts for them to discuss various aspects of it. In addition, the Delphi studies did not use the same method of reaching a consensus among the experts. Such a variety of approaches made universal conclusions more challenging. Moreover, it was not possible to comparatively measure the suggested competencies across all Delphi studies and come up with, for example, the ten competencies with the highest consensus scores. In spite of these limitations, the competencies across the Delphi studies had striking similarities and could therefore be grouped or categorised easily. This indicates that experts who have experience in cultural competence see similar competencies or skills as necessary for effectively working with diverse populations.

References

- Curry-Stevens, A.; Reyes, M.-E. Coalition of Communities of Color. Protocol for Culturally Responsive Organizations; Center to Advance Racial Equity, Portland State University: Portland, OR, USA, 2014.

- Betancourt, J.R.; Green, A.R.; Carrillo, J.E.; Ananeh-Firempong, O. Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003, 118, 293–302.

- Price, E.G.; Beach, M.C.; Gary, T.L.; Robinson, K.A.; Gozu, A.; Palacio, A.; Smarth, C.; Jenckes, M.; Feuerstein, C.; Bass, E.B.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Methodological Rigor of Studies Evaluating Cultural Competence Training of Health Professionals. Acad. Med. 2005, 80, 578–586.

- Renzaho, A.M.N.; Romios, P.; Crock, C.; Sønderlund, A.L. The effectiveness of cultural competence programs in ethnic minority patient-centered health care—A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2013, 25, 261–269.

- Horvat, L.; Horey, D.; Romios, P.; Kis-Rigo, J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014.

- Alizadeh, S.; Chavan, M. Cultural competence dimensions and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Health Soc. Care Community 2016, 24, e117–e130.

- Vella, E.; White, V.M.; Livingston, P. Does cultural competence training for health professionals impact culturally and linguistically diverse patient outcomes? A systematic review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 118, 105500.

- Chae, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Park, S. Effectiveness of cultural competence educational interventions on health professionals and patient outcomes: A systematic review. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 17, e12326.

- Skipworth, A. Systematic Review of the Association between Cultural Competence and the Quality of Care Provided by Health Personnel. 2021. Available online: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1855&context=honorsprojects (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Kleinman, A.; Benson, P. Anthropology in the Clinic: The Problem of Cultural Competency and How to Fix It. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e294.

- Costa, D. Diversity and Health: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Ital. Sociol. Rev. 2023, 13, 69–90.

- Mills, C.W. The Sociological Imagination; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959.

- Silverman, J.; Kurtz, S.; Draper, J. Skills for Communicating with Patients, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2013.

- Hughes, T.M.; Merath, K.; Chen, Q.; Sun, S.; Palmer, E.; Idrees, J.J.; Okunrintemi, V.; Squires, M.; Beal, E.W.; Pawlik, T.M. Association of shared decision-making on patient-reported health outcomes and healthcare utilization. Am. J. Surg. 2018, 216, 7–12.

- Ziegler, S.; Michaëlis, C.; Sørensen, J. Diversity Competence in Healthcare: Experts’ Views on the Most Important Skills in Caring for Migrant and Minority Patients. Societies 2022, 12, 43.

- Chae, D.; Kim, H.; Yoo, J.Y.; Lee, J. Agreement on Core Components of an E-Learning Cultural Competence Program for Public Health Workers in South Korea: A Delphi Study. Asian Nurs. Res. 2019, 13, 184–191.

- Farokhzadian, J.; Nematollahi, M.; Nayeri, N.D.; Faramarzpour, M. Using a model to design, implement, and evaluate a training program for improving cultural competence among undergraduate nursing students: A mixed methods study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 85.

More

Information

Subjects:

Health Policy & Services

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

778

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

25 May 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No