Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fengxue Xin | -- | 3129 | 2023-05-08 02:59:45 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 3129 | 2023-05-08 03:06:14 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Jiang, W.; Chen, X.; Feng, Y.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. Biological Production of Vanillin. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43947 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Jiang W, Chen X, Feng Y, Sun J, Jiang Y, Zhang W, et al. Biological Production of Vanillin. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43947. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Jiang, Wankui, Xiaoyue Chen, Yifan Feng, Jingxiang Sun, Yujia Jiang, Wenming Zhang, Fengxue Xin, Min Jiang. "Biological Production of Vanillin" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43947 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Jiang, W., Chen, X., Feng, Y., Sun, J., Jiang, Y., Zhang, W., Xin, F., & Jiang, M. (2023, May 08). Biological Production of Vanillin. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43947

Jiang, Wankui, et al. "Biological Production of Vanillin." Encyclopedia. Web. 08 May, 2023.

Copy Citation

Vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde), the primary ingredient in vanilla bean or pod extracts, possesses a rich, creamy, and distinctive vanilla smell, which is also one of the most significant aromas in the world. Vanillin can serve as a flavoring agent in the food industry (about 60%), a pharmaceutical intermediate in the pharmaceutical industry (about 7%), and a scent ingredient in the cosmetics sector (about 33%).

vanillin

ferulic acid

bioconversion

process optimization

1. Introduction

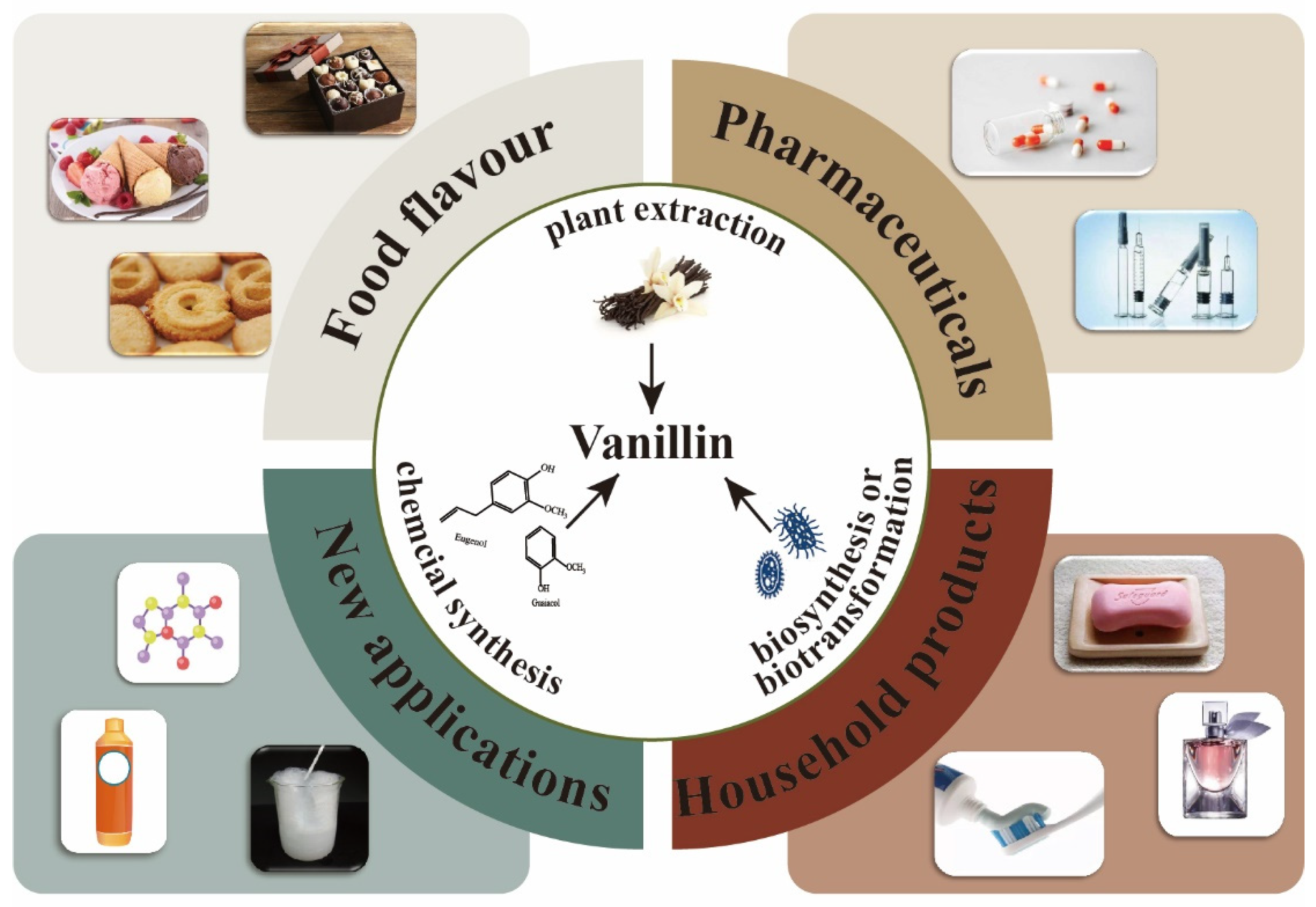

Vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde), the primary ingredient in vanilla bean or pod extracts, possesses a rich, creamy, and distinctive vanilla smell, which is also one of the most significant aromas in the world. Vanillin can serve as a flavoring agent in the food industry (about 60%), a pharmaceutical intermediate in the pharmaceutical industry (about 7%), and a scent ingredient in the cosmetics sector (about 33%) (Figure 1) [1][2]. The market demand for vanillin reached 18,600 tons globally by 2016, and its demand is predicted to grow at a CAGR of 7.4% from 2017 to 2025, indicating great market potential [3][4].

Figure 1. Vanillin production methods and applications.

At present, three methods are mainly used for vanillin production: plant extraction, chemical synthesis, and biosynthesis. Natural vanillin is generally extracted from vanilla, orchids, and other plants, which is very expensive, with a price of USD 1200 to USD 4000 per kilogram. As this process is significantly affected by the plant’s development cycle, growing environment, and processing costs, the natural extraction of vanillin cannot satisfy market demand [5]. Currently, chemical synthesis is the main method used for the industrial-scale production of vanillin. Compared with natural extraction, the market price of chemically synthesized vanillin is only 1% of natural vanillin (about USD 10 per kg) [6].

Chemically synthesized vanillin is mainly used for the synthesis of some polymers, deodorants, floor polishes, etc. [1]. Although vanillin is an essential flavoring ingredient, the use of chemically synthesized vanillin is prohibited in food and some other industries [4]. Additionally, the harsh conditions and human toxicity potential of chemically synthesized vanillin have caused some environmental concerns and energy waste [7]. With the rapid development of synthetic biology, the biological production of some natural products from renewable resources through microbial fermentation has gained great attention owing to their high selectivity and environmentally friendly properties [8]. In terms of vanillin production, it can be either de novo synthesized or transformed from some substrates such as eugenol, isoeugenol, and ferulic acid through microbial or enzymatic conversion [1].

2. Biological Production of Vanillin from Ferulic Acid

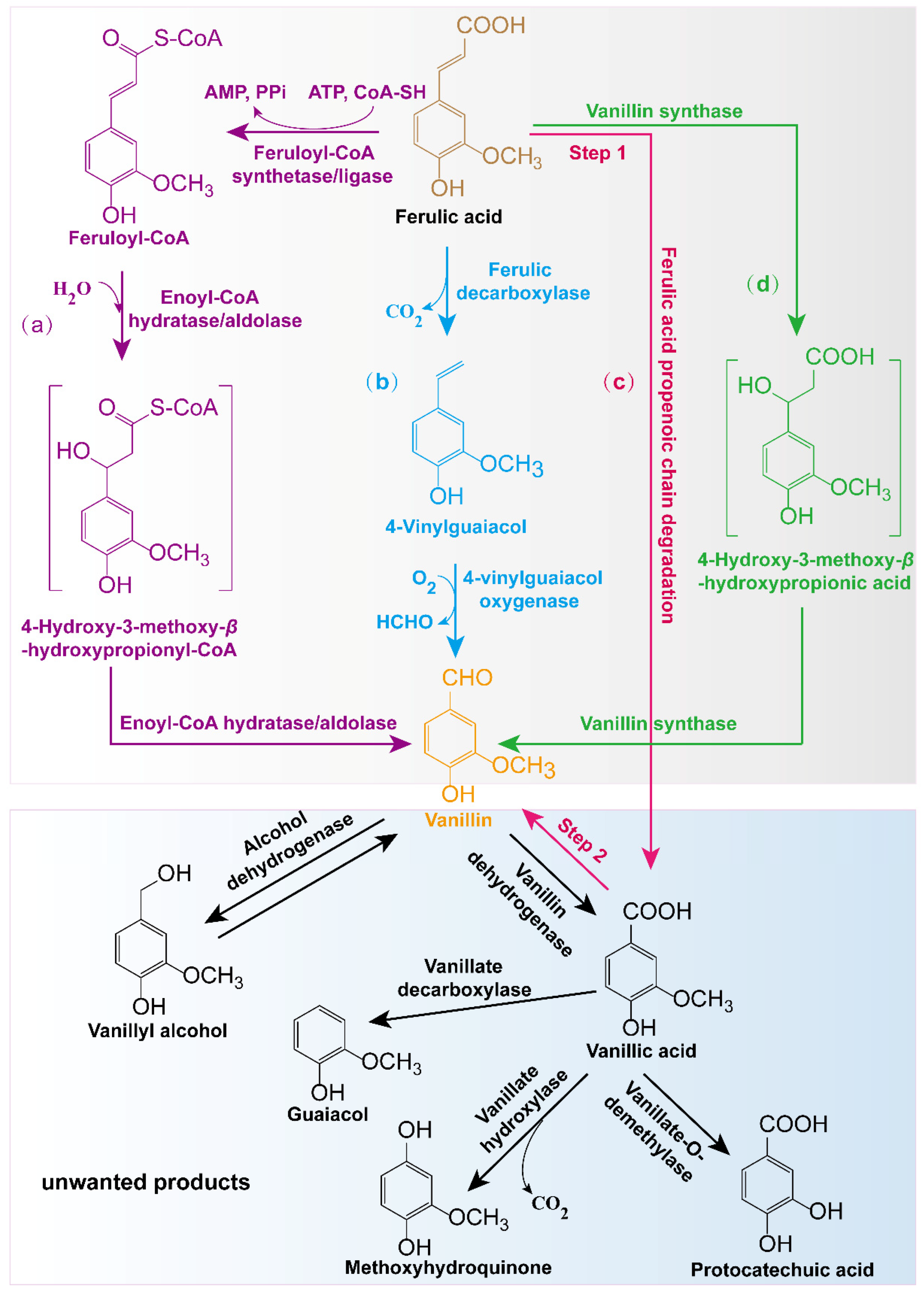

In nature, vanillin can be de novo synthesized by some plants and microorganisms. Furthermore, some enzymes can also transform vanillin precursors such as ferulic acid, eugenol, isoeugenol, phenolic stilbenes, etc., into vanillin [2]. Among these precursors, the most extensively used is ferulic acid, which is a cinnamic acid derivative naturally found in some plant cells (Figure 2) [3].

Figure 2. Pathways for the production of ferulic acid-derived vanillin using biotransformation methods and related producers: (a) CoA-dependent conversion in most microorganisms or engineered bacteria such as Amycolatopsis, Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6, Streptomyces, Pediococcus acidilactici BD16, and E. coli [3][9]; (b) CoA-independent conversion designed in recombinant E. coli [10]; (c) a two-step conversion pathway for vanillin production combining Aspergillus niger and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus [11]; (d) a one-step synthetic pathway for the production of vanillin in plant cells [12].

In general, four metabolic pathways play a role in vanillin production using ferulic acid (Figure 2). The first one is the CoA-dependent transformation pathway existing in most microorganisms, such as Amycolatopsis, Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas, Streptomyces, and Streptococcus [3][9]. In this metabolic pathway, feruloyl-CoA is generated from ferulic acid in a reaction catalyzed by feruloyl-CoA synthetase/ligase Fcs, which can be further converted to 4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-β-hydroxypropionyl-CoA via the catalysis of enoyl-CoA hydratase/aldolase Ech. Then, vanillin is generated through further catalysis of Ech. The second method involves the CoA-independent conversion pathway [10]. In this metabolic pathway, ferulic acid first removes the carboxyl group to generate 4-vinylguaiacol under the catalysis of ferulic decarboxylase Fdc and then generates vanillin under the catalysis of 4-vinylguaiacol oxygenase Cso2. The third mechanism involves a two-step bioconversion process. In the first step, Aspergillus niger transforms ferulic acid into vanillic acid, and in the second step, vanillic acid is reduced to vanillin by Pycnoporus cinnabarinus. Although this biotransformation process has been reported, the specific functional enzymes involved in this transformation process are still unknown [11]. The fourth method is a one-step synthetic pathway found only in plant cells [12]. In this pathway, ferulic acid can directly generate vanillin via the continuous catalysis of vanillin synthase VpVAN (Figure 2).

In most cases, the biotransformation of ferulic acid using microbes involves well-known coenzyme A-dependent and non-β-oxidative pathways of ferulic acid to feruloyl-CoA and feruloyl-CoA to vanillin, which are catalyzed using the feruloyl-CoA synthetase (Fcs) and enoyl-CoA hydratase/aldolase (Ech), respectively [13]. This two-step metabolic process mainly involves fcs and ech genes and requires the participation of CoASH, ATP, and MgCl2 (Figure 2) [14].

2.1. Biotransformation of Ferulic Acid into Vanillin Using Native Microbial Strains

In 1996, researchers described a two-step process for vanillin production, in which two filamentous fungi were employed for the biotransformation of ferulic acid to vanillin. Within this system, A. niger can convert ferulic acid to vanillic acid with a molar yield of 88%, whereas Pycnoporus cinnabarinus reduces vanillic acid to vanillin with a molar yield of 22%. As P. cinnabarinus mainly converts vanillic acid to methoxyhydroquinone, the resulting vanillin content is relatively low [11]. However, this reaction can be optimized by adding cellobiose to the medium, which can induce changes in the metabolic pathway of P. cinnabarinus, and the molar yield of vanillin can be increased by 51.7% [15]. Although this biotransformation process has been reported, the specific functional enzyme elements involved in this transformation process are still unknown [11].

Vanillin can be indigenously produced by many wild-type strains when ferulic acid is used as the substrate, including Corynebacterium glutamicum [16], Sphingomonas paucimobilis [17], wine-associated lactic acid bacteria [18], and Bacillus aryabhattai [19]. In particular, the Gram-positive bacteria Amycolatopsis sp. and Gram-negative Pseudomonas sp. are superior candidates for vanillin production owing to their robust tolerance to vanillin. Thus far, the highest 22.3 g/L of vanillin production has been obtained by the recombinant Amycolatoposis sp. ATCC 39116, in which the vanillin dehydrogenase gene (vdh) is knocked out, and feruloyl-CoA synthetase (Fcs) and enoyl-CoA hydratase/aldolase (Ech) are overexpressed [20][21]. In terms of the wild-type strain, Amycolatopsis sp. ATCC 39,116 led to the highest vanillin production rates through a multiple-pulse-feeding strategy with a production yield of 0.69 g vanillin/g ferulic acid [22]. However, it should be noted that the mycelial lysis entangled in viscous fermentation broths and unfavorable pellet formation increased the load in downstream process handling despite their considerable production advantages [9]. The P. putida KT2440 is a physiologically extremely versatile non-pathogenic bacterium that is applied as a “biosafety strain” in biotechnological processes, as authorized by the USA National Institute of Health [23]. P. putida KT2440vdhΩKm is a mutant with inactivated molybdate transporter. The conversion rate and molar yield of vanillin in this strain can reach 86% within 3 h [24]. Moreover, it is also reported that Streptomyces sp.V-1 has a high vanillin production capacity, which reaches 5 g/L using fed-batch fermentation [25][26].

Many of the natural strains used for vanillin synthesis not only have the pathway to synthesize vanillin but also the pathway to further metabolize vanillin [20]. For example, some microorganisms can use vanillin as a source of carbon and energy for their growth and metabolism, further causing the continued conversion of vanillin to other products. In some bacteria, vanillin dehydrogenase (Vdh) has been identified to catabolize lignin-derived aromatics, demonstrating catalytic activity for a wide range of aromatic substrates, including p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde, O-phthaldialdehyde, cinnamaldehyde, syringaldehyde, and benzaldehyde [16][17][27]. Vdh uses NAD+ or NADP+ as co-factors, facilitating the continuous oxidization of vanillin to vanillic acid [16][20]. Vanillic acid can be further metabolized to guaiacol or protocatechuate with the catalysis of vdcBCD and vanAB, respectively (Figure 2) [28][29]. Additionally, it was found that after the knockout of the vdh gene, Amycolatoposis sp. ATCC 39116ΔVdh reduced vanillin catabolism by nearly 90%, while the final concentration of vanillin reached 2.2 g/L [21]. Even though most studies focused on the inactivation of vanillin dehydrogenase (Vdh) to block the vanillin catabolic pathway, the problem of vanillin degradation still cannot be resolved since some microbes have additional complex competing degradation processes. For example, it was revealed that even after the inactivation of the vdh gene in P. putida KT2440 via the insertion of Ω elements, the variant P. putida KT2440 vdhΩKm was still able to grow on vanillin owing to the influence of other aldehyde dehydrogenases [23][30].

2.2. Biotransformation of Ferulic Acid into Vanillin Using Engineered Microbes

The application of genetic engineering to modify model strains opens up a new opportunity for high vanillin production. In terms of vanillin synthesis, model microorganisms, such as Escherichia coli or Saccharomyces cerevisiae, have been genetically modified for vanillin production because of their clear genetic background and relative ease of cultivation (Table 1). Currently, researchers have focused on vanillin conversion from ferulic acid via the heterologous expression of fcs and ech genes (encoding feruloyl-CoA synthetase and enoyl-CoA hydratase/aldolase) in model microorganisms in the context of whole-cell or cell-free catalytic systems [4][31][32][33][34]. Lee et al. suggested a unique metabolic engineering concept for recombinant E. coli introduced with fcs and ech genes to satisfy the need for coenzymes in this pathway [35]. Furthermore, the TCA cycle was modified to encourage the use of the glyoxylate bypass and increase the conversion of the extra acetyl-CoA produced via the ferulic acid metabolic pathway into the CoA needed for the coenzyme A-dependent non-β-oxidative pathway. Under these strategies, the production of vanillin reached 5.14 g/L, and the molar conversion rate was 86.6% within 24 h of fermentation [35].

Table 1. Synthesis of vanillin using engineered strains.

| Substrate | Strain | Main Strategies | Production | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eugenol | Recombinant Escherichia coli | Coexpression of vaoA, calA, calB, fcs, and ech genes. | 0.3 g/L | [36] |

| Ferulic acid | Recombinant Escherichia coli JM109-FE-F | Construction of an efficient cell-free catalytic system with FCS-Str and ECH-Str combination at 1:1; using resting cells | 2.3 g/L | [32] |

| Recombinant Escherichia coli FR13 | Integration of Fcs and Ech onto chromosomes; using resting cells; fed-batch fermentation; using a two-phase (solid–liquid) system | 4.3 g/L | [4] | |

| Recombinant Escherichia coli top 10 | Introduction of the cloned vanillin biosynthetic gene cassette in the pCCIBAC expression vector | 0. 068 g/L | [32] | |

| Recombinant Escherichia coli | Using a model-driven approach to fine-tune nutrients | 0.91 g/L | [33] | |

| Recombinant Escherichia coli | Using a two-pot bioprocess; introduction of fdc and cso2 genes; designing the cultivation medium | 7.9 g/L | [10] | |

| Recombinant Escherichia coli NTG-VR1 | Production of vanillin plasmid pTAHEF containing fcs and ech genes; using NTG mutagenesis; employing 50% (w/v) of XAD-2 resin | 2.9 g/L | [34] | |

| Recombinant Escherichia coli | Coexpression of gltA, icdA, fcs, and ech genes. | 5.1 g/L | [35] | |

| L-tyrosine, glucose, xylose, glycerol | Recombinant Escherichia coli | Mimicking the construction of the phenylpropanoid pathway in microorganisms and inducing five enzymes | 0.097 g/L, 0.019 g/L, 0.013 g/L, 0.024 g/L | [37] |

| Glucose | Recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Using an in silico strategy based on the strain S. cerevisiae | 0.500 g/L | [38] |

| Recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Coexpression of four genes: 3DSD, ACAR, OMT, and UGT | 0.045 g/L | [39] | |

| Isoeugenol | Recombinant Escherichia coli | Overexpression of isoeugenol monooxygenase; employing the magnetic chitosan membrane | 38.3 g/L | [40] |

| Recombinant Escherichia coli | Expression of the IEM720 gene; employing the sol–gel chitosan membrane | 4.5 g/L | [41] | |

| Recombinant Escherichia coli | Introduction of a plasmid with the isoeugenol monooxygenase gene | 28.3 g/L | [42] |

Moreover, a new coenzyme-independent two-pot vanillin biosynthetic pathway has been designed in E. coli to address the complexity of the catalytic process and the costly addition of cofactors. During this process, ferulic acid decarboxylase (Fdc) from B. pumilus ATCC 14,884 catalyzes the conversion of ferulic acid to 4-vinylguaiacol, and 4-vinylguaiacol oxygenase from Caulobacter segnis ATCC 21,756 (Cso2) catalyzes the conversion of 4-vinylguaiacol to vanillin, both of which are overexpressed in E. coli (Figure 2). Finally, the production of vanillin synthesized by the genetically engineered E. coli reached 7.8 g/L [10]. Furthermore, two Cso2 mutants, A49P and Q390A, were successfully obtained using a site mutagenesis strategy, which increased the vanillin yield by 18–25% [43]. Currently, the genetic instability of recombinant strains is still a bottleneck in the existing research on genetically modified organisms. How to enhance the expression of vanillin synthesis genes in microorganisms while maintaining stable strain production may be a future direction for vanillin production using genetically engineered microorganisms.

2.3. Synthesis of Vanillin from Ferulic Acid Using Plants

As stated above, natural vanillin generally exists in the pods of V. planifolia in the form of glycoside, which can protect plants from vanillin toxicity [39]. The synthesis of vanillin from endogenous ferulic acid in plants is mainly achieved with vanillin synthetase (VpVAN). VpVAN was first reported in V. planifolia [44][45]. Glechoma hederacea is another vanillin-producing plant, whose vanillin synthase shares 71% sequence identity with VpVAN in V. planifolia [12]. Chee et al. modified vanillin production in plant systems by using the callus tissues containing a codon-optimized VpVAN gene from Capsicum frutescens, and the vanillin content of transformed calli reached 0.057% (wild-type sample without vanillin) [46]. The vanillin yield can reach 544.72 μg/g in the fresh callus of rice cell culture after the overexpression of the vanillin synthase gene (VpVAN) in rice [47]. The use of plants to synthesize vanillin is affected by field conditions, growth environment, and processing costs, which leads to insufficient output to meet the market demand.

3. Vanillin Bioproduction from Lignin

Lignin is the most abundant aromatic polymer in nature, which can be converted to aromatic monomers via the action of depolymerizing enzymes [48]. Various fungi and bacteria have the ability to break down lignin, which can secrete laccase, manganese peroxidase (MnP), lignin peroxidase (LiP), dye-decolorizing peroxidase (DyP), and versatile peroxidases (VP) [49]. Basidiomycetous fungi (white rot and brown rot) have been extensively studied to achieve vanillin production from lignin [50]. For example, Phanerochaete chrysosporium NCIM 1197 can produce 55 μg/mL of vanillin from groundnut shell after 72 h [51]. Some bacteria such as Staphylococcus lentus can produce 72.55 mg/L vanillin from 2000 mg/L Kraft lignin after 6 days at 35 °C [52]. B. pumilus ZB1 also has the potential to transform guaiacyl lignin monomers, and 61.1% of isoeugenol and eugenol in 10 g/L of pyrolyzed masson pine bio-oil could be converted to 56.09 mg/L vanillin by B. pumilus ZB1 [53].

Recently, some genetically modified microbes have also been developed to realize vanillin production from lignin. For instance, after the deletion of the gene encoding vanillin dehydrogenase (vdh), which is responsible for the conversion of vanillin to vanillic acid, the lignin-degrading strain Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 accumulated 96 mg/L of vanillin after 144 h of culture with 2.5% wheatgrass lignocellulose [28][54]. In another study, the recombinant B. ligniniphilus L1 with the knockout of vanillin dehydrogenase accumulated 352 mg/L of vanillin with a conversion yield of 1.76% [55]. As microorganisms are less able to utilize water-insoluble or macromolecular lignin, biotransformation can be combined with physical or chemical methods to pre-treat such substrates to a fragmented or water-soluble, low-molecular-weight depolymerized form, which presumably allows microorganisms (especially bacteria) to assimilate lignin degradation products more efficiently [56].

4. Vanillin Production Using Other Substrates

Due to the extensive presence of ferulic acid in agro-industrial byproducts, such as sugar beet pulp, rice bran, wheat bran, and maize bran, many efforts have been directed toward achieving vanillin production from these wastes (Table 2) [57]. For instance, a natural bacterial consortium can synthesize 0.9 mg/mL vanillin from bamboo chips [58], and 708 mg/L of vanillin can be synthesized from ferulic acid in wheat bran [59].

Table 2. Synthesis of vanillin from different substrates.

| Microorganism | Substrate | Time | Yield | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediococcus acidilactici BD16 (fcs+/ech+) | Rice bran containing 0.257 mM FA | 24 h | 4.0 g/L | [60] |

| Aspergillus niger CGMCC0774 and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus CGMCC1115 | Rice bran oil | 72 h | 2.8 g/L | [61] |

| Streptomyces sannanensis MTCC 6637 | Wheat bran | 5 d | 0.71 g/L | [59] |

| E. coli strain JM109(pBB1) | Wheat bran containing ferulic acid | - | 2.5 g/L | [62] |

| 14 natural bacterial consortium | Bamboo chips from Bambusa tulda (ligno-cellulosic biomass) |

8 d | 0.9 g/L | [58] |

| Aspergillus niger I -1472 and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus MUCL 39532 | Sugar beet pulp | 8 d | 0.11 g/L | [63] |

| A. niger I-1472 and P. cinnabarinus MUCL39533 | Maize bran | 7–8 d | 0.77 g/L | [64] |

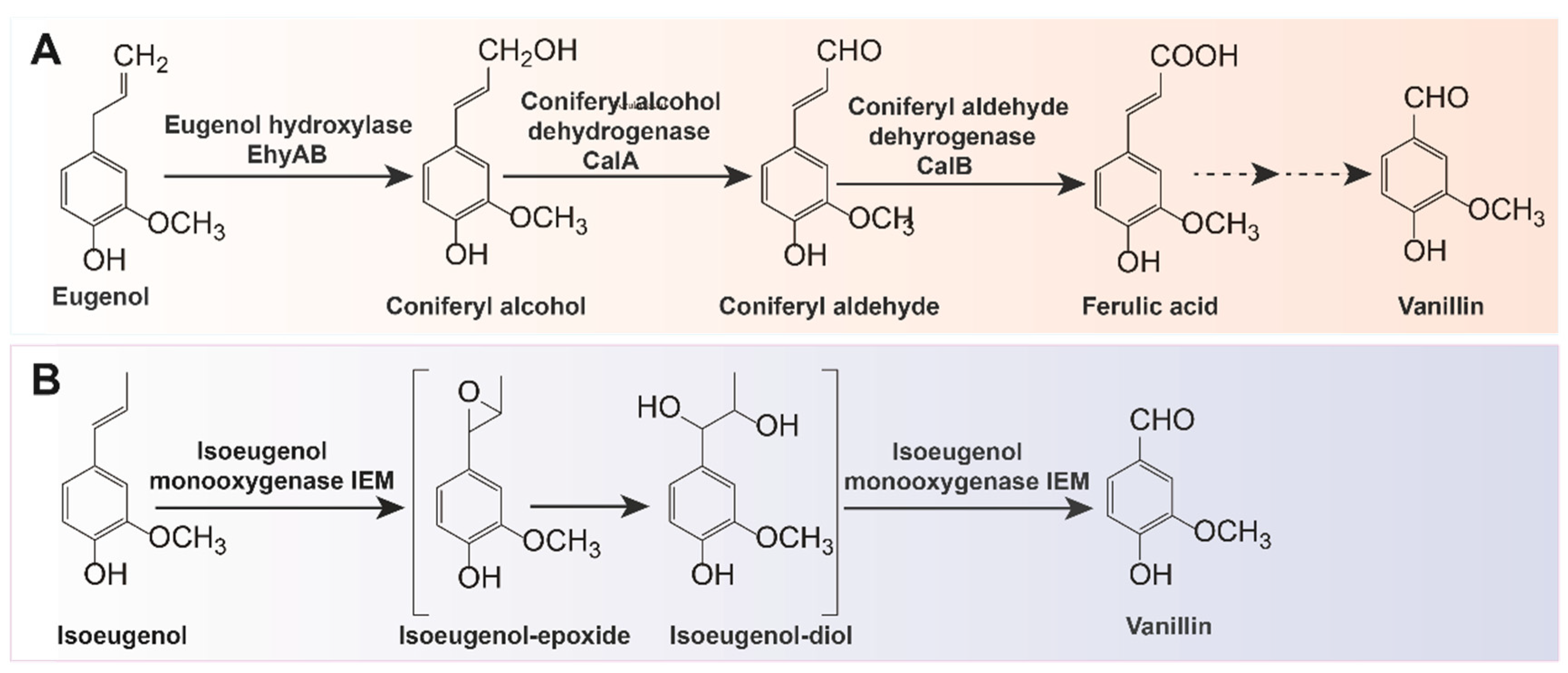

In addition to using ferulic acid derived from agricultural waste products as substrates, the biotransformation of other precursors such as eugenol or isoeugenol is also an alternative method for vanillin production. Eugenol can be converted to vanillin using microorganisms such as Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 [65], Rhodococcus sp. [66], Serratia marcescens [67], and B. cereus NCIM-5727 [68]. In terms of strain HR199 (DSM7063), the enzymatic conversion of eugenol to vanillin via coniferyl alcohol, coniferyl aldehyde, and ferulic acid pathway has been thoroughly explored (Figure 3A). The mutant Pseudomonas sp. strain HRvdhΩKm obtained by knocking out the vanillin metabolism gene was able to accumulate up to 2.9 mM vanillin in a mineral medium with 6.5 mM eugenol [36]. Currently, Bacillus sp., including B. subtilis HS8, B. aryabhattai BA03, and B. pumilus S-1, as well as Pseudomonas sp., including P. putida IE27, P. nitroreducens Jin1, and P. aeruginosa ISPC2), are the two main native strains known to produce vanillin by metabolizing isoeugenol [69][70][71][72][73][74][75]. The one-step conversion of isoeugenol to vanillin involves two enzymes: lipoxygenase (LOX) and isoeugenol monooxygenase (IEM) [76]. For the latter, researchers have successively identified, purified, and characterized isoprenol monooxygenase (IEM) from P. putida IE27 and P. nitroreducens Jin1, which can convert isoeugenol into vanillin without adding cofactors (Figure 3B) [77][78]. To further increase enzyme activity and eliminate unwanted byproducts, IEM can be modified and overexpressed in E. coli. The final vanillin concentration can reach 4.5 g/L (about 75% conversion) by using the site-saturation mutagenesis strategy in IEM based on the selection of a “three-criteria” in silico system for a favorable substitution position [41]. IEM can also be fused with amphiphilic short peptide 18A to boost the catalytic activity of this active aggregate IEM720-18A and improve the enzymatic stability through immobilization methods [79]. Additionally, a combinatorial strategy can be used to improve the enzymatic thermostability with a vanillin production rate of 240.1 mM [40][80].

Figure 3. Two biotransformation pathways of vanillin: (A) biotransformation pathway from eugenol to vanillin; (B) biotransformation pathway from isoeugenol to vanillin.

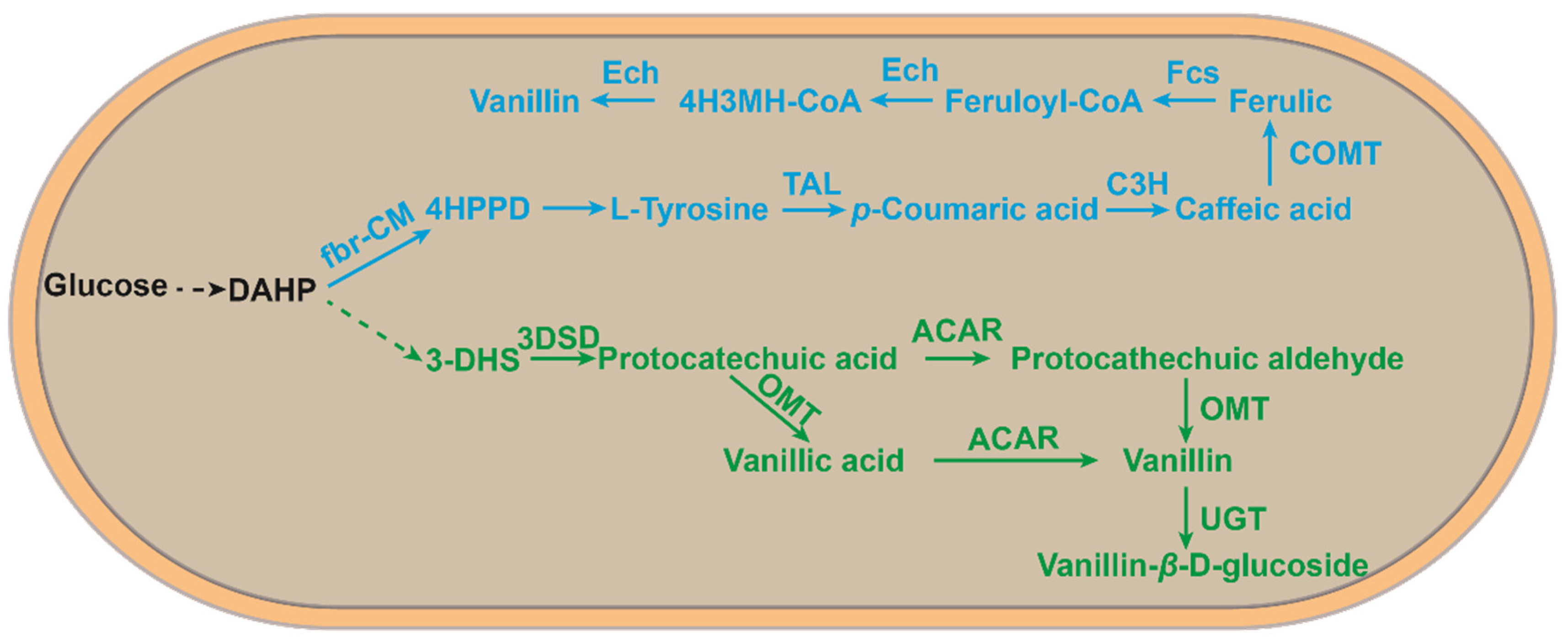

To further reduce production costs, researchers have explored the de novo synthesis of vanillin from glucose (Figure 4). Hansen et al. first developed the recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae VAN286 with the introduction of a shikimic acid pathway in S. cerevisiae to achieve the de novo synthesis of vanillin from glucose. The resulting vanillin concentration was 45 mg/L [39]. Afterward, Brochado et al. developed a metabolically engineered S. cerevisiae using a silico metabolic engineering strategy. The vanillin glucoside produced was 500 mg/L [38]. This method was mimicked in the assembly of a natural pathway in E. coli for the de novo synthesis of vanillin using glucose (19.3 mg/L vanillin), tyrosine (97.2 mg/L vanillin), xylose (13.3 mg/L vanillin), and glycerol (24.7 mg/L) with less impact on host cell metabolism and potential to exploit tyrosine as a substrate [37].

Figure 4. An artificial microbial route to de novo synthesis from glucose to vanillin. The blue part is a new vanillin synthesis route developed in E. coli by means of the L-tyrosine pathway [37]; the green part is a vanillin synthesis route developed in S. cerevisiae via the 3-dehydromangiferic acid pathway [39]. DAHP, 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate; 4-HPPD, 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate; 4H3MH-CoA, 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl-β-hydroxypropionyl-CoA; 3-DHS,3-dehydroshikimate; Fbr-CM, fbr-chorismate mutase; TAL, tyrosine ammonia-lyase; C3H, 4-coumarate 3-hydroxylase; COMT, caffeate O-methyltransferase; FCS, feruloyl-CoA synthetase; ECH, enoyl-CoA hydratase/aldolase; 3DSD, 3-dedhydroshikimate dehydratase; ACAR, aryl carboxylic acid reductase; OMT, O-methyltransferase; UGT, UDP-glycosyltransferase.

References

- Banerjee, G.; Chattopadhyay, P. Vanillin biotechnology: The perspectives and future. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 499–506.

- Priefert, H.; Rabenhorst, J.; Steinbüchel, A. Biotechnological production of vanillin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 56, 296–314.

- Gallage, N.J.; Møller, B.L. Vanillin-bioconversion and bioengineering of the most popular plant flavor and its de novo biosynthesis in the vanilla orchid. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 40–57.

- Martău, G.A.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Vodnar, D.C. Bio-vanillin: Towards a sustainable industrial production. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 579–592.

- Walton, N.J.; Mayer, M.J.; Arjan, N. Molecules of interest vanillin. Phytochesmistry 2003, 63, 505–515.

- Fache, M.; Boutevin, B.; Caillol, S. Vanillin production from lignin and its use as a renewable chemical. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 35–46.

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Sun, H.; Bai, S.; Li, C. Identifying environmental hotspots and improvement strategies of vanillin production with life cycle assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144771.

- Ciriminna, R.; Fidalgo, A.; Meneguzzo, F.; Parrino, F.; Ilharco, L.M.; Pagliaro, M. Vanillin: The case for greener production driven by sustainability megatrend. ChemistryOpen 2019, 8, 660–667.

- Galadima, A.I.; Salleh, M.M.; Hussin, H.; Chong, C.S.; Yahya, A.; Mohamad, S.E.; Abd-Aziz, S.; Yusof, N.N.M.; Naser, M.A.; Al-Junid, A.F.M. Biovanillin: Production concepts and prevention of side product formation. Biomass Convers. Bior. 2020, 10, 589–609.

- Furuya, T.; Kuroiwa, M.; Kino, K. Biotechnological production of vanillin using immobilized enzymes. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 243, 25–28.

- Lesage-Meessen, L.; Delattre, M.; Haon, M.; Thibault, J.F.; Ceccaldi, B.C.; Brunerie, P.; Asther, M. A two-step bioconversion process for vanillin production from ferulic acid combining Aspergillus niger and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus. J. Biotechnol. 1996, 50, 107–113.

- Gallage, N.J.; Hansen, E.H.; Kannangara, R.; Olsen, C.E.; Motawia, M.S.; Jørgensen, K.; Holme, I.; Hebelstrup, K.; Grisoni, M.; Møller, B.L. Vanillin formation from ferulic acid in Vanilla planifolia is catalysed by a single enzyme. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4037.

- Overhage, J.; Priefert, H.; Steinbüchel, A. Biochemical and genetic analyses of ferulic acid catabolism in Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 4837–4847.

- Narbad, A.; Gasson, M.J. Metabolism of ferulic acid via vanillin using a novel CoA-dependent pathway in a newly-isolated strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Microbiology 1998, 144, 1397–1405.

- Lesage-Meessen, L.; Haon, M.; Delattre, M.; Thibault, J.F.; Ceccaldi, B.C.; Asther, M. An attempt to channel the transformation of vanillic acid into vanillin by controlling methoxyhydroquinone formation in Pycnoporus cinnabarinus with cellobiose. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1997, 47, 393–397.

- Ding, W.; Si, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Z.; Chen, S.; Shen, X. Functional characterization of a vanillin dehydrogenase in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8044.

- Varman, A.M.; He, L.; Follenfant, R.; Wu, W.; Wemmer, S.; Wrobel, S.A.; Tang, Y.J.; Singh, S. Decoding how a soil bacterium extracts building blocks and metabolic energy from ligninolysis provides road map for lignin valorization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5802–E5811.

- Bloem, A.; Bertrand, A.; Lonvaud-Funel, A.; de Revel, G. Vanillin production from simple phenols by wine-associated lactic acid bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 44, 62–67.

- Paz, A.; Carballo, J.; Pérez, M.J.; Domínguez, J.M. Bacillus aryabhattai BA03: A novel approach to the production of natural value-added compounds. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 159.

- Fleige, C.; Hansen, G.; Kroll, J.; Steinbüchel, A. Investigation of the Amycolatopsis sp. strain ATCC 39116 vanillin dehydrogenase and its impact on the biotechnical production of vanillin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 81–90.

- Fleige, C.; Meyer, F.; Steinbüchel, A. Metabolic engineering of the actinomycete Amycolatopsis sp. strain ATCC 39116 towards enhanced production of natural vanillin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 3410–3419.

- Valério, R.; Bernardino, A.R.; Torres, C.A.; Brazinha, C.; Tavares, M.L.; Crespo, J.G.; Reis, M.A. Feeding strategies to optimize vanillin production by Amycolatopsis sp. ATCC 39116. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 44, 737–747.

- Plaggenborg, R.; Overhage, J.; Steinbüchel, A.; Priefert, H. Functional analyses of genes involved in the metabolism of ferulic acid in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 61, 528–535.

- Graf, N.; Altenbuchner, J. Genetic engineering of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 for rapid and high-yield production of vanillin from ferulic acid. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 137–149.

- Hua, D.; Ma, C.; Song, L.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Xu, P. Enhanced vanillin production from ferulic acid using adsorbent resin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 783–790.

- Yang, W.; Tang, H.; Ni, J.; Wu, Q.; Hua, D.; Tao, F.; Xu, P. Characterization of two Streptomyces enzymes that convert ferulic acid to vanillin. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67339.

- Di Gioia, D.; Luziatelli, F.; Negroni, A.; Ficca, A.G.; Fava, F.; Ruzzi, M. Metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas fluorescens for the production of vanillin from ferulic acid. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 156, 309–316.

- Chen, H.P.; Chow, M.; Liu, C.C.; Lau, A.; Liu, J.; Eltis, L.D. Vanillin catabolism in Rhodococcus jostii RHA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 586–588.

- Meyer, F.; Pupkes, H.; Steinbüchel, A. Development of an improved system for the generation of knockout mutants of Amycolatopsis sp. strain ATCC 39116. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e02660-e16.

- Simon, O.; Klaiber, I.; Huber, A.; Pfannstiel, J. Comprehensive proteome analysis of the response of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 to the flavor compound vanillin. J. Proteom. 2014, 109, 212–227.

- Chakraborty, D.; Gupta, G.; Kaur, B. Metabolic engineering of E. coli top 10 for production of vanillin through FA catabolic pathway and bioprocess optimization using RSM. Protein Expr. Purification 2016, 128, 123–133.

- Chen, Q.H.; Xie, D.T.; Qiang, S.; Hu, C.Y.; Meng, Y.H. Developing efficient vanillin biosynthesis system by regulating feruloyl-CoA synthetase and enoyl-CoA hydratase enzymes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 247–259.

- Yeoh, J.W.; Jayaraman, S.S.; Tan, S.G.; Jayaraman, P.; Holowko, M.B.; Zhang, J.; Kang, C.W.; Leo, H.L.; Poh, C.L. A model-driven approach towards rational microbial bioprocess optimization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 305–318.

- Yoon, S.H.; Li, C.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, J.Y.; Choi, M.S.; Seo, W.T.; Yang, J.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.W. Production of vanillin by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Lett. 2005, 27, 1829–1832.

- Lee, E.G.; Yoon, S.H.; Das, A.; Lee, S.H.; Li, C.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, M.S.; Oh, D.K.; Kim, S.W. Directing vanillin production from ferulic acid by increased acetyl-CoA consumption in recombinant. Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009, 102, 200–208.

- Overhage, J.; Steinbüchel, A.; Priefert, H. Highly efficient biotransformation of eugenol to ferulic acid and further conversion to vanillin in recombinant strains of Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 6569–6576.

- Ni, J.; Tao, F.; Du, H.; Xu, P. Mimicking a natural pathway for de novo biosynthesis: Natural vanillin production from accessible carbon sources. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13670.

- Brochado, A.R.; Matos, C.; Møller, B.L.; Hansen, J.; Mortensen, U.H.; Patil, K.R. Improved vanillin production in baker’s yeast through in silico design. Microb. Cell Fact. 2010, 9, 1–15.

- Hansen, E.H.; Møller, B.L.; Kock, G.R.; Bünner, C.M.; Kristensen, C.; Jensen, O.R.; Okkels, F.T.; Olsen, C.E.; Motawia, M.S.; Hansen, J. De novo biosynthesis of vanillin in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) and baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 2765–2774.

- Wang, Q.; Wu, X.; Lu, X.; He, Y.; Ma, B.; Xu, Y. Efficient biosynthesis of vanillin from isoeugenol by recombinant isoeugenol monooxygenase from Pseudomonas nitroreducens Jin1. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 193, 1116–1128.

- Zhao, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, L.; Xu, X.; Zhao, C.X.; Cheng, F. Efficient biotransformation of isoeugenol to vanillin in recombinant strains of Escherichia coli by using engineered isoeugenol monooxygenase and sol-gel chitosan membrane. Process Biochem. 2018, 71, 76–81.

- Yamada, M.; Okada, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Nagasawa, T. Vanillin production using Escherichia coli cells over-expressing isoeugenol monooxygenase of Pseudomonas putida. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 30, 665–670.

- Yao, X.; Lv, Y.; Yu, H.; Cao, H.; Wang, L.; Wen, B.; Gu, T.; Wang, F.; Sun, L.; Xin, F. Site-directed mutagenesis of coenzyme-independent carotenoid oxygenase CSO2 to enhance the enzymatic synthesis of vanillin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 3897–3907.

- Gallage, N.J.; Jørgensen, K.; Janfelt, C.; Nielsen, A.J.Z.; Naake, T.; Dunski, E.; Dalsten, L.; Grisoni, M.; Møller, B.L. The intracellular localization of the vanillin biosynthetic machinery in pods of Vanilla planifolia. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 304–318.

- Yang, H.; Barros-Rios, J.; Kourteva, G.; Rao, X.; Chen, F.; Shen, H.; Liu, C.; Podstolski, A.; Belanger, F.; Havkin-Frenkel, D.; et al. A re-evaluation of the final step of vanillin biosynthesis in the orchid Vanilla planifolia. Phytochemistry. 2017, 139, 33–46.

- Chee, M.J.Y.; Lycett, G.W.; Khoo, T.J.; Chin, C.F. Bioengineering of the plant culture of Capsicum frutescens with vanillin synthase gene for the production of vanillin. Mol. Biotechnol. 2017, 59, 1–8.

- Arya, S.S.; Mahto, B.K.; Sengar, M.S.; Rookes, J.E.; Cahill, D.M.; Lenka, S.K. Metabolic engineering of rice cells with vanillin synthase gene (VpVAN) to produce vanillin. Mol. Biotechnol. 2022, 64, 861–872.

- Jiang, W.; Gao, H.; Sun, J.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, M.; Xin, F. Current status, challenges and prospects for lignin valorization by using Rhodococcus sp. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 60, 108004.

- Brown, M.E.; Chang, M.C. Exploring bacterial lignin degradation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014, 19, 1–7.

- Lundell, T.K.; Mäkelä, M.R.; Hildén, K. Lignin-modifying enzymes in filamentous basidiomycetes-ecological, functional and phylogenetic review. J. Basic Microbiol. 2010, 50, 5–20.

- Karode, B.; Patil, U.; Jobanputra, A. Biotransformation of low cost lignocellulosic substrate into vanillin by white rot fungus, Phanerochaete chrysosporium NCIM 1197. Indian J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 281–283.

- Baghel, S.; Anandkumar, J. Biodepolymerization of kraft lignin for production and optimization of vanillin using mixed bacterial culture. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 8, 100335.

- Zuo, K.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Ran, Q.; Huang, M.; Cui, X.; He, L.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Z. Effective biotransformation of variety of guaiacyl lignin monomers into vanillin by Bacillus pumilus. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 901690.

- Sainsbury, P.D.; Hardiman, E.M.; Ahmad, M.; Otani, H.; Seghezzi, N.; Eltis, L.D.; Bugg, T.D. Breaking down lignin to high-value chemicals: The conversion of lignocellulose to vanillin in a gene deletion mutant of Rhodococcus jostii RHA1. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2151–2156.

- Zhu, D.; Xu, L.; Sethupathy, S.; Si, H.; Ahmad, F.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Yang, B.; Sun, J. Decoding lignin valorization pathways in the extremophilic Bacillus ligniniphilus L1 for vanillin biosynthesis. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 9554–9570.

- Xu, Z.; Lei, P.; Zhai, R.; Wen, Z.; Jin, M. Recent advances in lignin valorization with bacterial cultures: Microorganisms, metabolic pathways, and bio-products. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 32.

- Zamzuri, N.A.; Abd-Aziz, S. Biovanillin from agro wastes as an alternative food flavour. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2013, 93, 429–438.

- Harshvardhan, K.; Suri, M.; Goswami, A.; Goswami, T. Biological approach for the production of vanillin from lignocellulosic biomass (Bambusa tulda). J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 485–490.

- Chattopadhyay, P.; Banerjee, G.; Sen, S.K. Cleaner production of vanillin through biotransformation of ferulic acid esters from agroresidue by Streptomyces sannanensis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 272–279.

- Chakraborty, D.; Selvam, A.; Kaur, B.; Wong, J.W.C.; Karthikeyan, O.P. Application of recombinant Pediococcus acidilactici BD16 (fcs+/ech+) for bioconversion of agrowaste to vanillin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 5615–5626.

- Zheng, L.; Zheng, P.; Sun, Z.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, X. Production of vanillin from waste residue of rice bran oil by Aspergillus niger and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 1115–1119.

- Barghini, P.; Di Gioia, D.; Fava, F.; Ruzzi, M. Vanillin production using metabolically engineered Escherichia coli under non-growing conditions. Microb. Cell Fact. 2007, 6, 1–11.

- Lesage-Meessen, L.; Lomascolo, A.; Bonnin, E.; Thibault, J.F.; Buleon, A.; Roller, M.; Asther, M.; Record, E.; Ceccaldi, B.C.; Asther, M. A biotechnological process involving filamentous fungi to produce natural crystalline vanillin from maize bran. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2002, 102, 141–153.

- Lesage-Meessen, L.; Stentelaire, C.; Lomascolo, A.; Couteau, D.; Asther, M.; Moukha, S.; Moukha, S.; Record, E.; Sigoillot, J.; Asther, M. Fungal transformation of ferulic acid from sugar beet pulp to natural vanillin. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1999, 79, 487–490.

- Rabenhorst, J. Production of methoxyphenol-type natural aroma chemicals by biotransformation of eugenol with a new Pseudomonas sp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1996, 46, 470–474.

- Plaggenborg, R.; Overhage, J.; Loos, A.; Archer, J.A.; Lessard, P.; Sinskey, A.J.; Steinbüchel, A.; Priefert, H. Potential of Rhodococcus strains for biotechnological vanillin production from ferulic acid and eugenol. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 72, 745–755.

- Khanafari, A.; Olia, M.S.J.; Sharifnia, F. Bioconversion of essential oil from plants with eugenol bases to vanillin by Serratia marcescens. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2011, 14, 229–240.

- Singh, A.; Mukhopadhyay, K.; Ghosh Sachan, S. Enhanced vanillin production from eugenol by Bacillus cereus NCIM-5727. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 1811–1824.

- Hua, D.; Ma, C.; Lin, S.; Song, L.; Deng, Z.; Maomy, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, B.; Xu, P. Biotransformation of isoeugenol to vanillin by a newly isolated Bacillus pumilus strain: Identification of major metabolites. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 130, 463–470.

- Paz, A.; Costa-Trigo, I.; Tugores, F.; Míguez, M.; de la Montaña, J.; Domínguez, J.M. Biotransformation of phenolic compounds by Bacillus aryabhattai. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 1671–1679.

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, P.; Han, S.; Yan, H.; Ma, C. Metabolism of isoeugenol via isoeugenol-diol by a newly isolated strain of Bacillus subtilis HS8. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 73, 771–779.

- Ashengroph, M.; Nahvi, I.; Zarkesh-Esfahani, H.; Momenbeik, F. Use of growing cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for synthesis of the natural vanillin via conversion of isoeugenol. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2011, 10, 749–757.

- Haridoss, M.; Kamatchi, C.; Rafiq, Z.; Vaidyanathan, R. Biotransformation of isoeugenol to vanillin by beneficial bacteria isolated from the soil of aromatic plants. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2015, 7, 274–280.

- Unno, T.; Kim, S.J.; Kanaly, R.A.; Ahn, J.H.; Kang, S.I.; Hur, H.G. Metabolic characterization of newly isolated Pseudomonas nitroreducens Jin1 growing on eugenol and isoeugenol. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2007, 55, 8556–8561.

- Yamada, M.; Okada, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Nagasawa, T. Biotransformation of isoeugenol to vanillin by Pseudomonas putida IE27 cells. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 73, 1025–1030.

- Li, Y.H.; Sun, Z.H.; Zhao, L.Q.; Xu, Y. Bioconversion of isoeugenol into vanillin by crude enzyme extracted from soybean. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2005, 125, 1–10.

- Ryu, J.Y.; Seo, J.; Park, S.; Ahn, J.H.; Chong, Y.; Sadowsky, M.J.; Hur, H.G. Characterization of an isoeugenol monooxygenase (Iem) from Pseudomonas nitroreducens Jin1 that transforms isoeugenol to vanillin. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013, 77, 289–294.

- Yamada, M.; Okada, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Nagasawa, T. Purification, characterization and gene cloning of isoeugenol-degrading enzyme from Pseudomonas putida IE27. Arch. Microbiol. 2007, 187, 511–517.

- Zhao, L.; Jiang, Y.; Fang, H.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, S.; Rajoka, M.S.R.; Wu, Y. Biotransformation of isoeugenol into vanillin using immobilized recombinant cells containing isoeugenol monooxygenase active aggregates. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 189, 448–458.

- Lu, X.Y.; Wu, X.M.; Ma, B.D.; Xu, Y. Enhanced thermostability of Pseudomonas nitroreducens isoeugenol monooxygenase by the combinatorial strategy of surface residue replacement and consensus mutagenesis. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1199.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biotechnology & Applied Microbiology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

3.8K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

08 May 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No