Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jou-chun Lu | -- | 3659 | 2023-05-07 11:34:54 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 3659 | 2023-05-09 08:09:31 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Dal Martello, R.; Baeyer, V.M.; Hudson, M.; Bjorn, R.G.; Leipe, C.; Zach, B.; Mir-Makhamad, B.; Billings, T.N.; Muñoz Fernández, I.M.; Huber, B.; et al. The Domestication and Dispersal of Large-Fruiting Prunus spp.. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43936 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Dal Martello R, Baeyer VM, Hudson M, Bjorn RG, Leipe C, Zach B, et al. The Domestication and Dispersal of Large-Fruiting Prunus spp.. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43936. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Dal Martello, Rita, Von Madelynn Baeyer, Mark Hudson, Rasmus G. Bjorn, Christian Leipe, Barbara Zach, Basira Mir-Makhamad, Traci N. Billings, Irene M. Muñoz Fernández, Barbara Huber, et al. "The Domestication and Dispersal of Large-Fruiting Prunus spp." Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43936 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Dal Martello, R., Baeyer, V.M., Hudson, M., Bjorn, R.G., Leipe, C., Zach, B., Mir-Makhamad, B., Billings, T.N., Muñoz Fernández, I.M., Huber, B., Boxleitner, K., Lu, J., Chi, K., Liu, H., Kistler, L., & Spengler, R.N. (2023, May 07). The Domestication and Dispersal of Large-Fruiting Prunus spp.. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43936

Dal Martello, Rita, et al. "The Domestication and Dispersal of Large-Fruiting Prunus spp.." Encyclopedia. Web. 07 May, 2023.

Copy Citation

The Prunus genus contains many of the most economically significant arboreal crops, cultivated globally, today. Despite the economic significance of these domesticated species, the pre-cultivation ranges, processes of domestication, and routes of prehistoric dispersal for all of the economically significant species remain unresolved. Among the European plums, even the taxonomic classification has been heavily debated over the past several decades.

Prunus

plum

peach

apricot

domestication

horticulture

1. Introduction

Scholars argue that the domestication of perennial crops, such as fruit trees, took place several millennia after the domestication of annual herbaceous plants (i.e., cereals and legumes), due to the increased complexity and multi-year perspective and planning required for managing fruit trees before the first harvest [1][2][3][4], although there is some evidence that a few fruits could have been managed alongside cereals during a long period of pre-cultivation management [5]. Some scholars have suggested that fruit tree management was closely linked with the rise of urbanism, the establishment of reliable exchange networks and markets, and the development of new forms of land ownership [1]. This is partially due to the fact that most fruit species propagate better clonally through grafting or budding than when grown from the seed. Vegetative propagation offers the advantage of better selection control of preferential qualities and shortens the pre-maturity stage (the period prior to the first fruit production) over growing from seeds, which takes a minimum of three to five years [6][7]. The main measurable changes derived from human management include an increase in size and sugar content, reduction in acidity of the fruit, and a loss of spines on the branches [3]. Archaeobotanically, the most useful trait hypothesized to accompany the domestication of long-generation perennials is the elongation of the fruit seed [8]. This may be a vestige of their endozoochoric legacy, whereas a fruit seed that increases evenly in size will evolve to be too large for the disperser to swallow, while elongation still allows the seed to be consumed. Evidence for the consumption of Prunus fruits is attested by at least the Neolithic (c. 8/7th millennium B.C.E.) at the two ends of the Eurasian continent, with a marked increase in remains starting around the terminal 4th or early 3rd millennium B.C.E. [1]. While scholars assume that the early Prunus pits represent foraging from the wild, the transition from foraging—to managing wild population—to low-investment cultivation, likely of hedgerows or trees scattered around occupation sites—to full orchards and irrigated populations, remains poorly understood. Likewise, despite the long, archaeologically documented history of human consumption, and their substantial economic importance from antiquity to today, many questions about their evolutionary trajectories and especially how the domesticated forms came to be so widespread across Eurasia and North Africa remain unanswered.

1.1. Taxonomy of Plums

Debates and Identification Issues

The Prunus clade is situated within the Rosaceae family, one of the most widely cultivated families of angiosperms. Members of the family are prone to significant diversity under hybridization, leading to cultivated hybrid complexes, with individuals or genets often genetically locked into place through clonal reproduction. The subfamily Prunoideae is characterized by species that produce drupes known as “stone fruits” where the seed is encased in a hard, lignified endocarp referred to as the “stone”, and the fleshy portion is a sugary mesocarp. Both the Prunoideae and Maloideae subfamilies include avian-dispersed and megafruiting forms, with megafruits evolving at least twice following very different pathways towards pomes and drupes [9][10]. Over the past decade, much has been clarified regarding the domestication and dispersal of the apple (Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh.) [11][12][13][14], but economically important members of Prunoideae remain enigmatic. Many of the most consumed arboreal fruits of the world today are in Prunus, aclade consisting of more than 400 species, with wild and cultivated varieties distributed across the temperate regions of all continents [15][16]. Even the evolutionary history of members of the Prunus clade remains unsettled, with many contradictory systematics schemata [17].

There are many obstacles to studying the domestication and ancient dispersal of large-fruiting members of Prunus, including morphological similarities between the seeds/fruits of different clades and issues in taxonomic classification. Given the likelihood of hybridization across the family and the impressive ranges of phenotypic diversity in the clade, the phylogeny of large-fruiting members of Rosaceae has been challenging to parse out. As a result, many conflicting taxonomic systems exist (for a good summary, see Shi et al. [16]: Figure 1).

Figure 1. Photos of modern examples of Prunus stones by species. 1. Peach (collected by K. Boxleitner, 2021, Surungur, Kyrgyzstan); 2. Apricot (collected by K. Boxleitner, 2021, Obishir-5, Kyrgyzstan); 3. Sloe (seeds and fruit collected by R. Spengler, 2020, Jena, Germany, fruit not to scale); 4. Cherry plum (collected by B. Zach, 1993, Botanical Garden Hohenheim, Germany; fruit collected by R. Spengler 2022, Issyk-kul, Kyrghistan, not to scale); 5. insititia-type plum, stone and fruit (stone collected by B. Zach, 1985, Tübingen, Germany; fruit collected by R. Spengler 2020, Jena, Germany, not to scale); 6. domestica-type plum, stone and fruit (stone collected by B. Zach, 1992, Tübingen, Germany; fruit collected by R. Spengler 2020, Jena, Germany, not to scale). Stones from the Modern Fruit Plant Reference Collection, Paleoethnobotany Laboratories, Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, Jena.

When trying to integrate multiple lines of evidence, however, the lack of resolution within the nomenclature causes complications. When common names are used, especially in English, it is often unclear which species is being discussed; for example, with the term “damson” used indiscriminately to refer to both domestica and insititia type plums. This issue is less prominent within the archaeobotanical literature due to the use of Latin names; although, it is still a widespread practice across the popular literature (gardeners, garden centers, and plant aficionada). Issues still persist with regard to whether plums, especially domestica and insititia types, are to be considered two different species or two subspecies of P. domestica, as indicated above. In the academic literature, both views are used interchangeably among scholars, but with a more widespread use of the subspecies division. This is due to earlier classification systems put forward by European botanists and archaeobotanists, who classified plums into numerous subspecies and varieties based on both modern and ancient plum remains from Central Europe [18][19][20][21][22]. The most comprehensive modern Prunus classification was proposed by Koerber-Grohne [23] that combined archaeobotanical and modern material in line with current scientific nomenclature. Koerber-Grohne [23] favored a subspecies classification of domestica and insititia plums into P. domestica ssp. oeconomica and P. domestica ssp. insititia, listing numerous further varieties of each in what is still the most detailed work on ancient plum classification published to date.

1.2. Hypothesized Origins of Plum, Peaches, and Apricots

1.2.1. Plums and Sloes

The sloe is a native European species with clear morphological and genetic parameters and a native range spanning much of Europe. The cherry or myrobalan plum, domestica plum, and possibly insititia plum have all been at times suggested to also originate in Europe, with notable early archaeological remains of alleged wild insititia plum and cherry plum (cf. cerasifera plum) reported from sites in Germany [18][23] and Bulgaria (Gudzhova, Mogila) [24]. However, other scholars have suggested that they may have originated in Western or Central Asia [25][26], leaving each species’ center of origin largely unresolved. The lack of understanding has been further exacerbated by a dearth of archaeobotanical investigations in Central Asia until rather recently.

1.2.2. Apricots

It was accepted that the apricot originated in the Caucasus Mountains, likely tied to Pliny the Elder’s claim that the tree originated there combined with a strong cultural affinity for the fruit in that part of the world today. However, a series of studies over the past few years has found early remains of apricots along with peaches in eastern China [1][27]. The lack of identification of any early apricot remains in the Caucasus has challenged thisorigin hypothesis, but left open a debate over whether the apricot could have secondarily originated in a different part of Central Asia. Ecologists have claimed that the wild apricot has a range that spans from Eastern China all the way to the Tian Shan Mountains in Central Asia [28][29].

1.2.3. Peaches

The wild progenitor of the domesticated peach is unknown and most scholars believe it to be extinct. The scientific name for peach derives from the Greek persikon malon, and subsequently Latin malum persicum, meaning Persian apple, attesting to the early belief that peaches originated in Persia (or more generally somewhere to the east, as many customs and beliefs originating to the east of the Classical world were simply ascribed to Persia). This hypothesis was postulated by ancient Greek and Roman writers (see below) and adopted by European botanists before the 19th century [30].

2. The Domestication and Dispersal of Large-Fruiting Prunus spp.

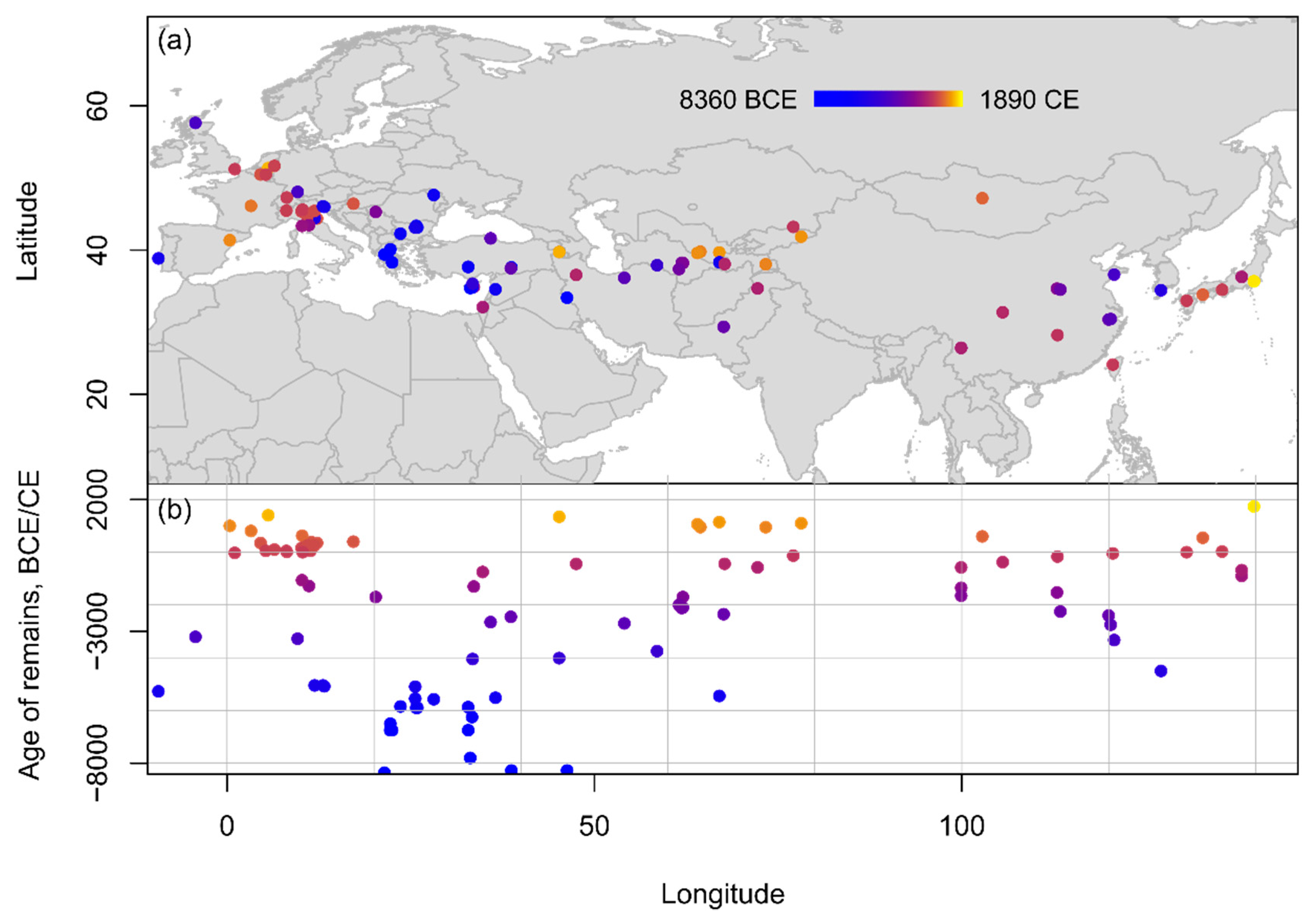

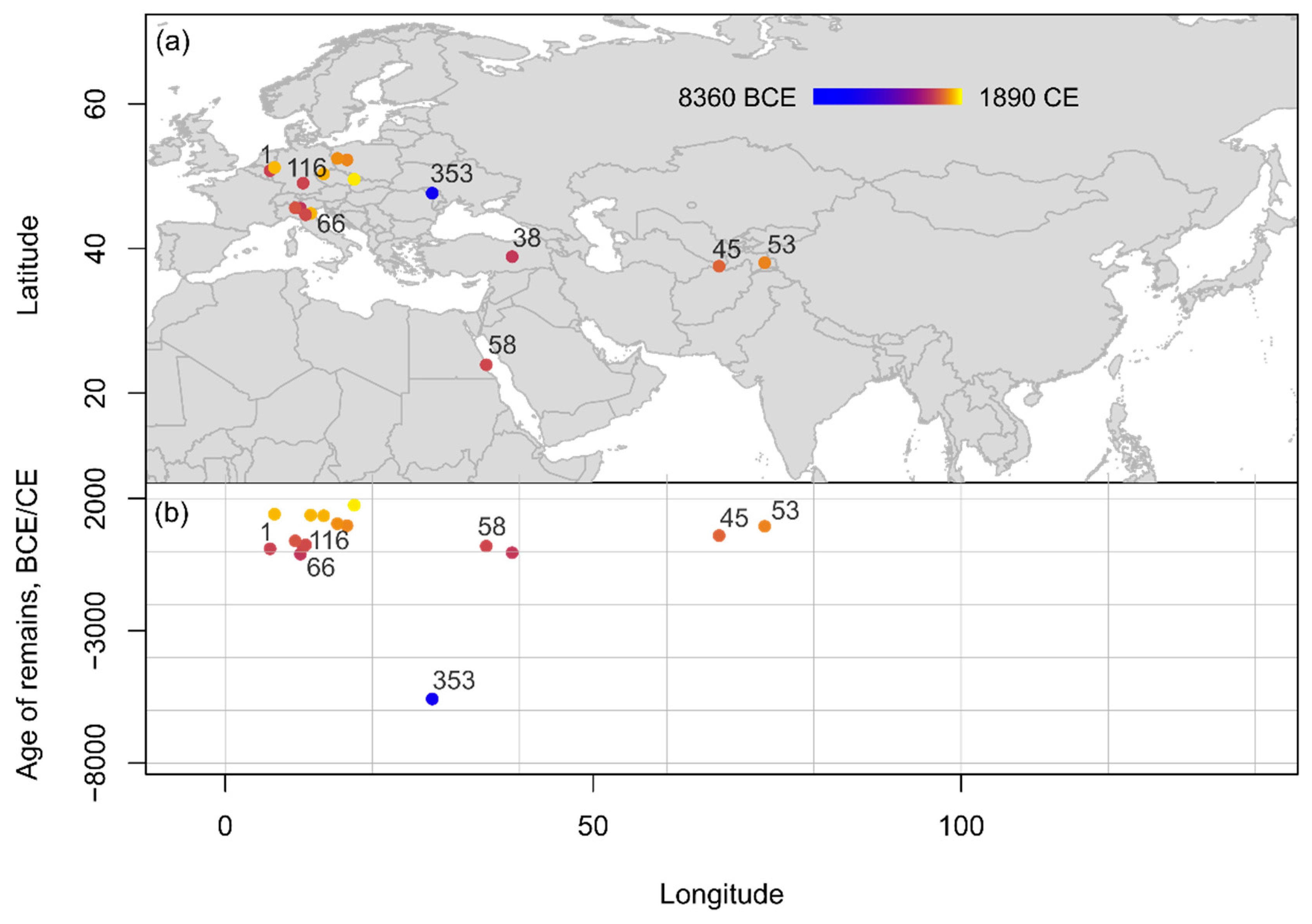

There is considerable unevenness in the number of published records for each species and across regions and time periods. Peach remains are the most reported species, followed by sloe, and then Prunus sp. Prunus sp. remains from East Asia may represent Japanese plums and apricots (P. mume and P. salicina), while Prunus sp. remains from Southwest Asia may represent almond (P. amygdalus Batsch) since these are native to these regions. The great number of archaeobotanical remains simply classified as Prunus sp. (Figure 2) attests to the difficulty of identifying archaeobotanical remains to species level. When the preservation status of the remains was available in the reports, it found that published Prunus remains were mostly charred or waterlogged (79 and 49 occurrences respectively, with multiple occurrences of unspecified “uncharred” remains), but stones were also preserved by desiccation and mineralization. In terms of recovery contexts, Prunus remains were found in a variety of contexts, including burials, dwellings, cesspits, hearths/ovens, or storage deposits, as well as general rubbish pits, wells, and cultural deposits. In most regions, outside Japan where fruit stones are often used to anchor ceramic chronologies, Prunus remains are usually not directly dated, with most sites in the database dated through either cultural association or radiocarbon dating on various associated archaeological material (bones, wood charcoal, or cereal grains). Beyond the already mentioned directly dated peach stones from Japan, it found only one other report of a directly dated peach stone from the tomb of Marquis Haihun in Nanchang, Jiangxi, China (95 B.C.E.–26 C.E.) [31], and one report of directly dated desiccated unspecified Prunus remains from Areni-1 in Armenia (4230–3800 B.C.E.) [32][33].

Figure 2. Spatio-temporal distribution of Prunus sp. remains from Eurasia compiled within the database shown (a) on a topographic map and (b) in an age-longitude plot.

2.1. Peach

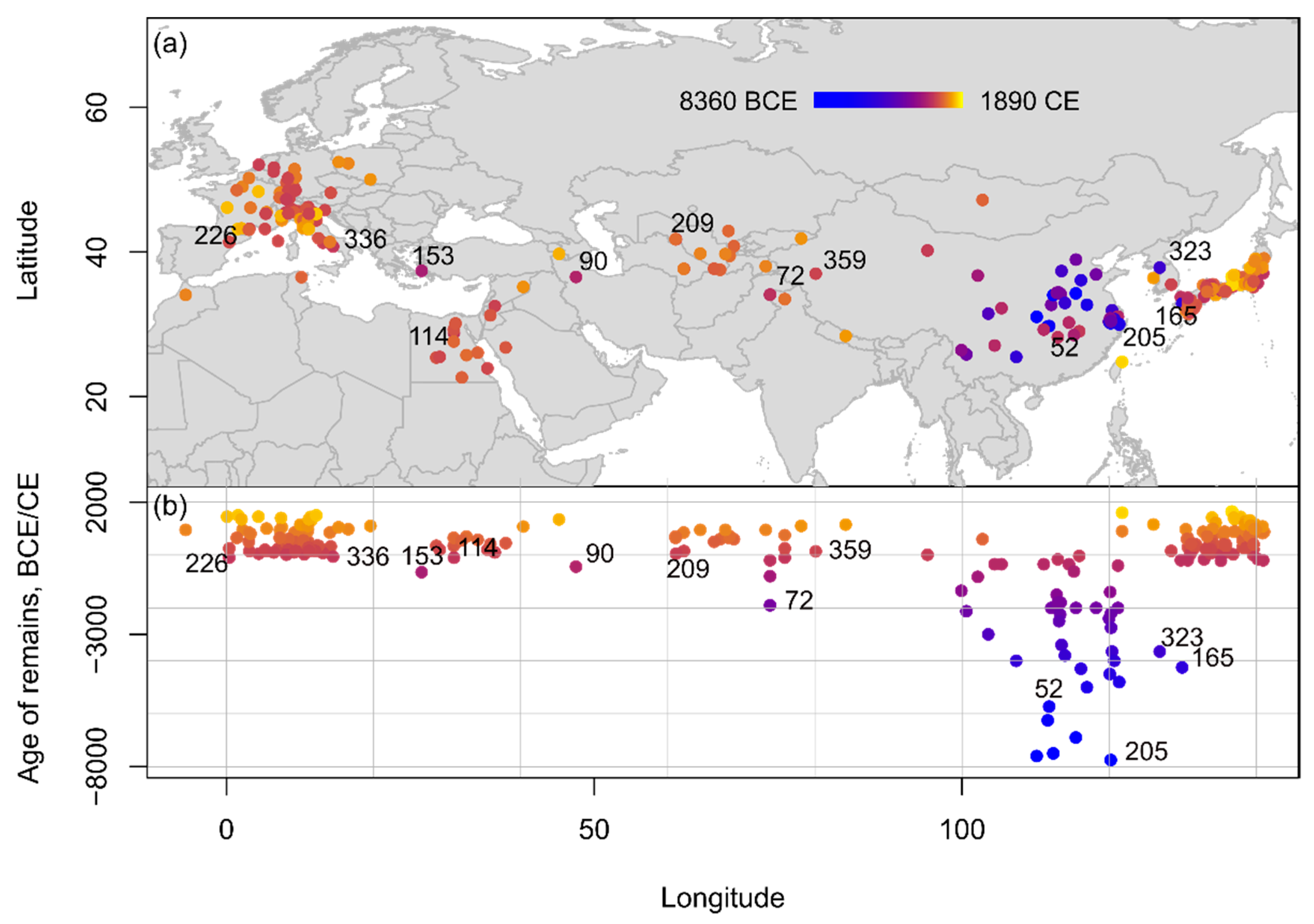

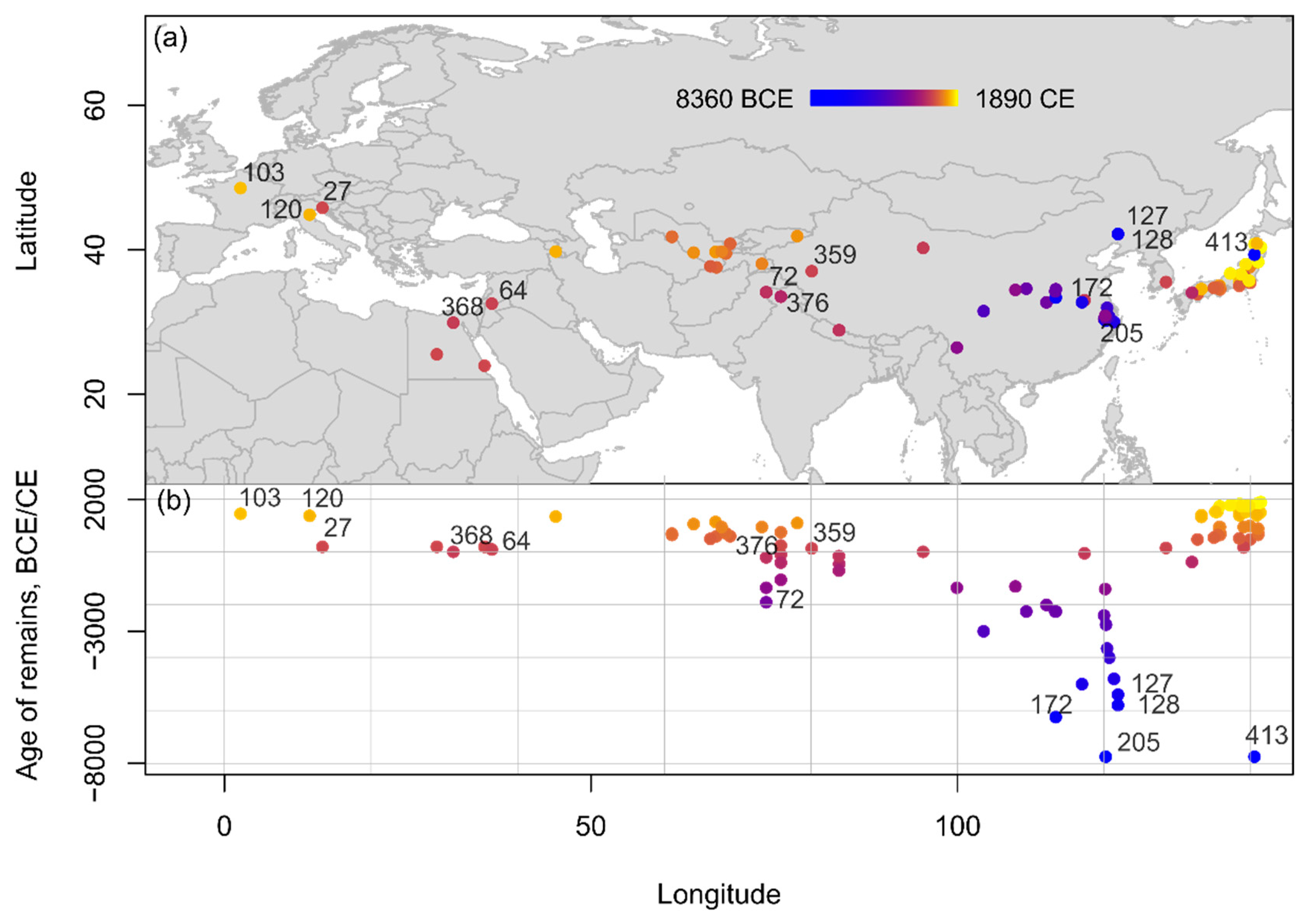

Archaeobotanically, peach is the most reported large-stone Prunus species, with 248 accounts of peaches from across all regions and time periods, but mostly found in East Asia, followed by Europe (Figure 3). Chronologically, peach stones first appear in the archaeological record of China from at least the 8th millennium B.C.E. At present the earliest sites with reported peach remains are Kuahuqiao in Zhejiang (8000–7500 B.C.E.) and Bashidang in Hunan (8500–7600 B.C.E.) [27]. There are no reported peach remains outside of modern mainland China from the 8th to the 5th/4th millennia B.C.E., until peach stones were reported at P’aju Taenŭngri in Korea (3900–3400 B.C.E., dated by cultural association) [34], and at Ikiriki in Nagasaki, Japan (5000–3500 B.C.E.). Peach finds from the Ikiriki site have been frequently discussed in the English literature, e.g., [35] and used to claim that the peach was introduced to Japan as early as the 5th millennium B.C.E. [27]. Ikiriki produced 19 peach stones [36] (p. 47); of these, three are from Layer III, which is dated broadly between the Yayoi to medieval periods. Layer IV, which lacked cultural artefacts, produced two stones. Another three stones came from Layer V, dated to the Late-Final Jōmon. Finally, there were ten examples from the Early Jōmon strata: six from Layer VII (associated with Sobata pottery) and four from Layer VIII (associated with Todoroki B pottery). As described in the site report, the stratigraphy at Ikiriki was, in places, disturbed by what the excavators termed ‘sand pipes’, traces of ancient animal burrowing. Of the ten Early Jōmon peach stones, nine come from deposits classified as type ‘a’ where the stratigraphic relationship with the ‘sand pipes’ is unclear. Only one example is type ‘b’, claimed to be from undisturbed deposits [36] (p. 47). These issues suggest that caution is required in accepting Ikiriki as an example of a pre-Bronze Age introduction of P. persica to Japan.

Figure 3. Spatio-temporal distribution of Prunus persica remains from Eurasia and Northern Africa compiled within the database shown (a) on a topographic map and (b) in an age-longitude plot. Sites mentioned in text listed in chronological order: 205: Kuahuqiao; 52: Bashidang; 165: Ikiriki; 323: P’aju Taenŭngri; 72: Burzahom; 153: Heraion; 90: Chehrabad; 114: el-Hibeh; 226: Lleida; 336: Pompeii; 209: Koy-Krilgan-kala; 359: Sampula.

The earliest report of peaches outside East Asia comes from Burzahom, in Kashmir, where it has been reported throughout the occupation of the site (2400–1400 B.C.E. and 1000 B.C.E.–200 C.E.) [37]. While a photo of one of the fragments has been published, it is not diagnostic from the image and there are no direct dates. In Southwest Asia, peach and plum stones have been found in association with ancient contexts in a collapsed salt mine in Chehrabad, Iran (550–330 B.C.E.) [38]. Peach stones have been reported from archaeological sites in Europe only from the Roman period/1st millennium B.C.E., for example at Heraion in Greece (700–600 B.C.E.) [39][40], Lleida in Spain (200–1 B.C.E.) [41], and throughout Italy, including Pompeii (200 B.C.E.–79 C.E.) [42][43] and northern Italy (100 B.C.E.–400 C.E.) [44].

2.2. Apricot

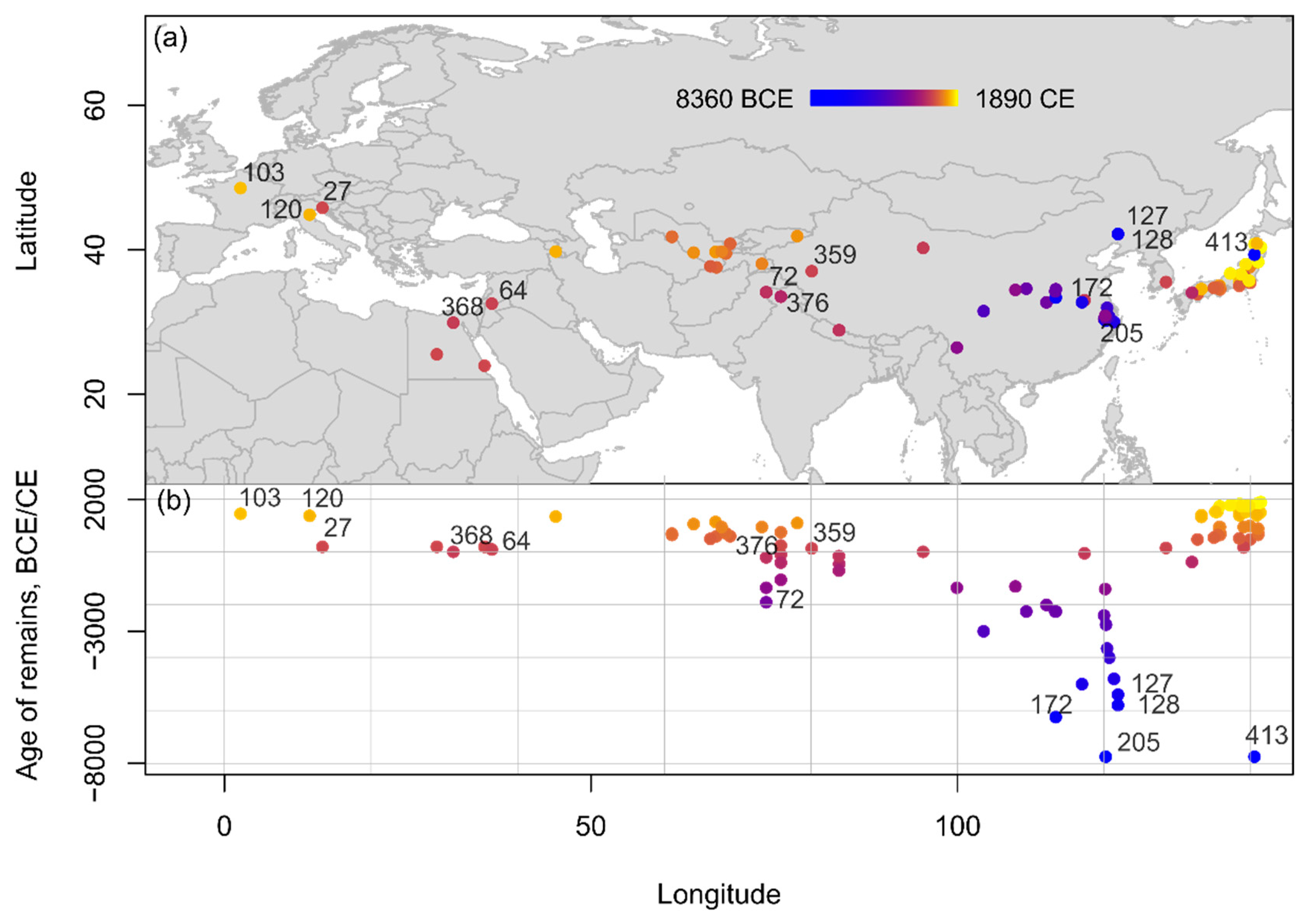

According to present evidence, the earliest apricot finds, dating to the 6th millennium B.C.E., come from modern mainland China, where apricot stones have been reported from the sites of Kuahuqiao in Zhejiang (8000–7500 B.C.E.) [27][45][46], Jiahu in Henan (7000–5500 B.C.E.) [47], Fuxin 12D56 (also known as Jiajiagou West, 5900–5700 B.C.E.), and Fuxin 12D16 (also known as Tachiyingzi, 5500–5300 B.C.E.) in Liaoning Province [48]. Within East Asia, some records of apricots are available from Japan. Most of these are assigned on stratigraphic grounds to the Kofun period (250–700 C.E.) or later. Two of the finds are assigned to the Yayoi period and one to the Neolithic Jōmon. The Jōmon apricot is reported from the Tetori-shimizu site [49]. According to the site report, a single apricot stone was found in grid NH72, a former stream deposit, which produced pottery from the Jōmon, Yayoi, and Kofun periods [49] (p. 108, 370). Discounting this ‘Jōmon’ find as likely contamination, current evidence suggests P. armeniaca was introduced to Japan during the Kofun period, or in the third century C.E. at the earliest.

Comparable with the peach, the apricot remains were confined to East Asia for several millennia before dispersing to the other regions (Figure 4). Only from the 3rd/2nd millennium B.C.E. have apricot remains been reported from southern Asia, at Burzahom (2400–1000 B.C.E.) and Semthan (1500–200 B.C.E.) in Kashmir [37], where peaches have also been found. The apricot seems to be a late comer to Central Asia, Africa, and Europe, reaching Central Asia only during the late 1st millennium B.C.E., as evidenced from remains from Sampula, in Xinjiang, China (55 B.C.E.–300 C.E. [50][51][52], where peaches were also reported. Apricots have been found at Saqqara in Egypt (330 B.C.E.–350 C.E.) [47], and Bosra in Syria (100 B.C.E.–300 C.E.) [47].

Figure 4. Spatio-temporal distribution of Prunus armeniaca remains from Eurasia and Northern Africa compiled within the database shown (a) on a topographic map and (b) in an age-longitude plot. Sites mentioned in text and listed chronologically: 205: Kuahuqiao; 172: Jiahu; 413: Tetori-shimizu; 128: Fuxin 12D56; 127: Fuxin 12D16; 72: Burzahom; 376: Semthan; 368: Saqqara; 64: Bosra; 359: Sampula; 27: Aquileia; 120: Ferrara; 103: Cour Carrée of Louvre.

2.3. Sloe and Plums

2.3.1. Sloe

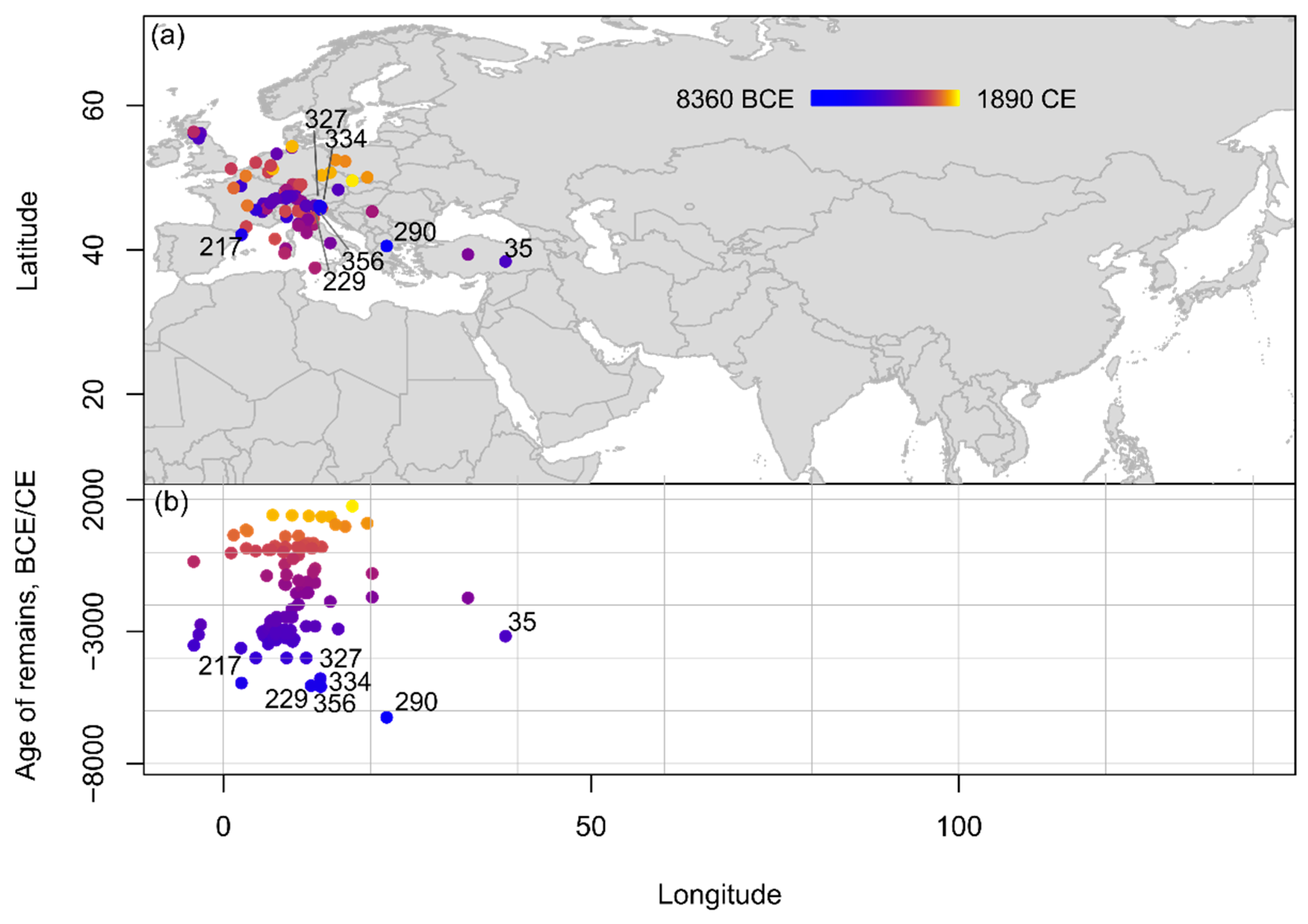

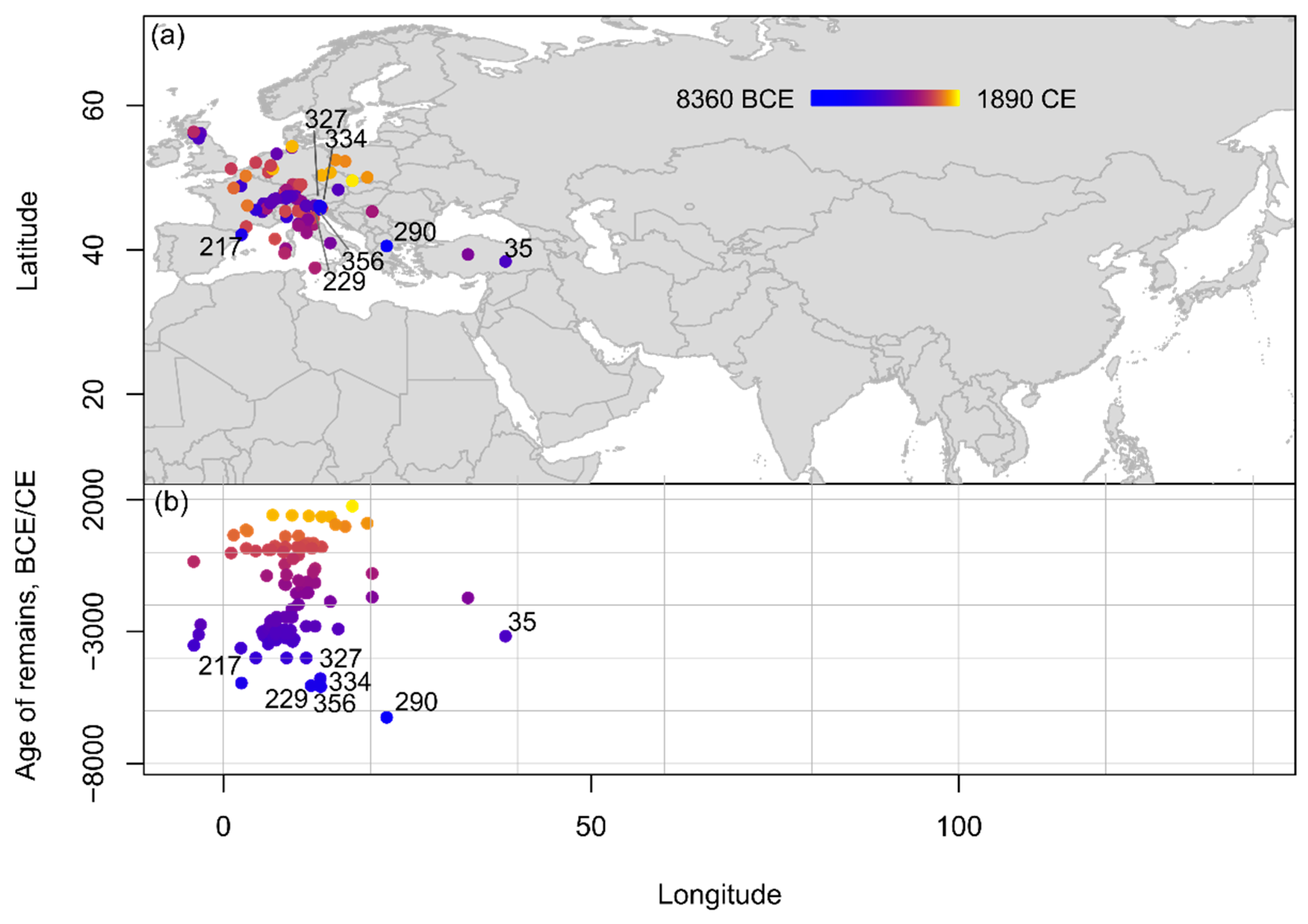

Sloe is considered a native species to Europe, and it is not surprising that most of the records for this species come from this region, with only one report from West Asia and no other finds from any of the other regions (Figure 5). Sloe remains are reported from at least the 7th/6th millennium B.C.E. from broader southern Europe, including at Nea Nikomedeia in Greece (6400–6100 B.C.E.) [53][54], Sammardenchia, Lugo di Romagna, Piancada and Pavia di Udine in Italy (6th/5th millennium B.C.E.) [55][56][57], and La Draga in Spain (5400–4500 B.C.E.) [58]. Chronologically, there are no notable differences in the presence of sloe remains across time in Europe.

Figure 5. Spatio-temporal distribution of Prunus spinosa remains from Eurasia and Northern Africa compiled within the database shown (a) on a topographic map and (b) in an age-longitude plot. Sites mentioned in text and listed chronologically: 290: Nea Nikomedeia; 356: Sammardecchia; 229: Lugo di Romagna; 334: Piancada; 217: La Draga; 327: Pavia di Udine; 35: Arslantepe.

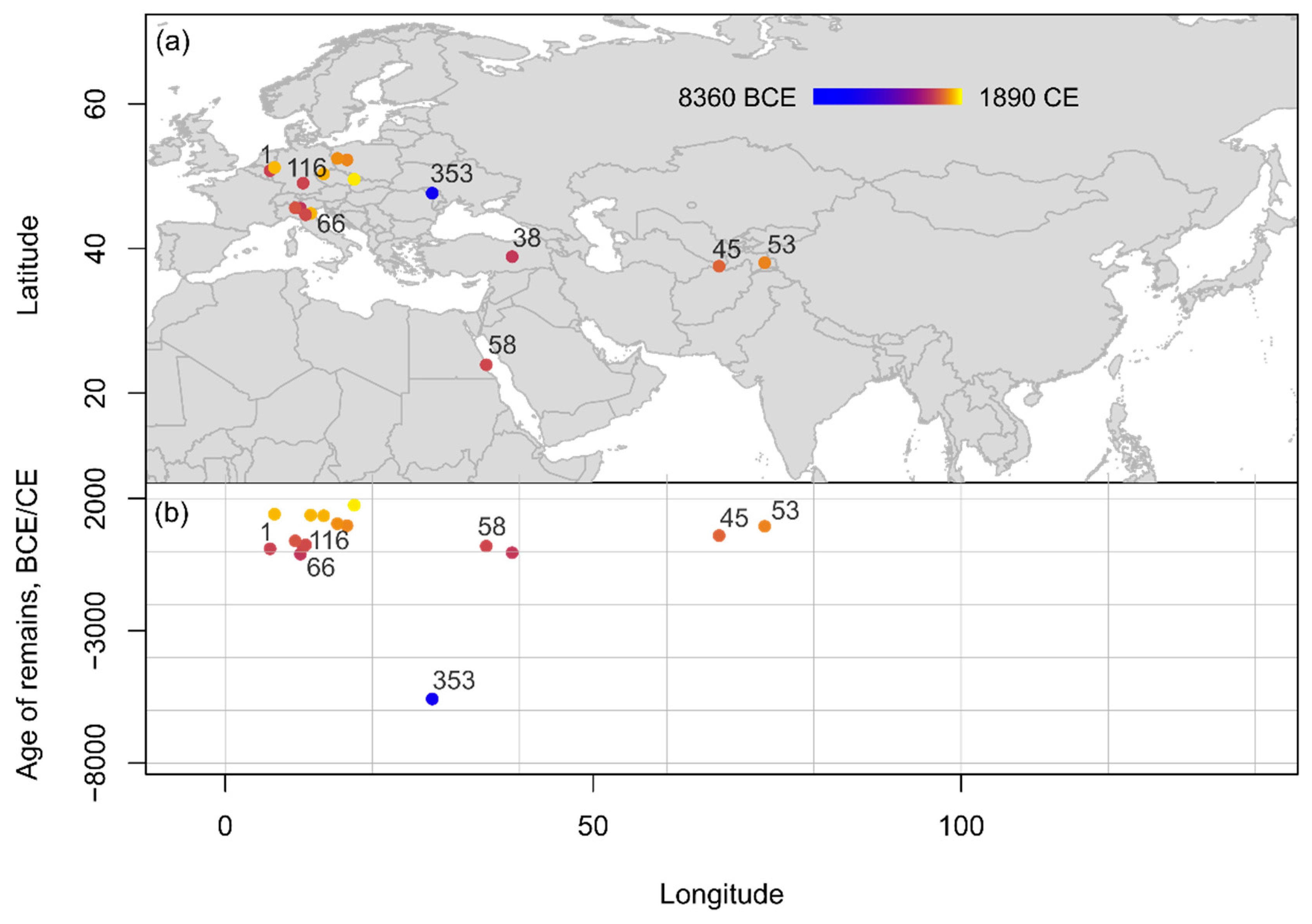

3.3.2. Cherry Plum

Cherry plum records are the least abundant across all regions (Figure 6). Chronologically, there is only one possible record of cherry plum dating to an early age; this comes from Sacarovca in Moldova (5650–5500 B.C.E.) [59]. All other reports date to much later, at the earliest to the very end of the 1st millennium B.C.E. onward. Cherry plum has been reported from Aşvan Kale (Hell) in Turkey (100–1 B.C.E., so far this is also the only reported cherry plum record from Southwest Asia) [60]; Aachen-Burtscheid (50–150 C.E.) [61] and Ellingen in Germany (115–211 C.E.) [62], and Berenike in Egypt (1–400 C.E.; this is also the only record from Northeast Africa) [63]. In Central Asia, cherry plum has been reported even later than that reported in the other regions, from the medieval sites of Balalyk Tepe in Uzbekistan (500–700 C.E.) [64], and at the site of Bazar-Dara in Tajikistan (800–1100 C.E.) [65], where over 10,000 cherry plum pits have been reported. Bazar-Dara is located at nearly 4000 m asl; since plums cannot grow at such a high altitude, the fruits might have been transported to the site preserved, either dried or fermented.

Figure 6. Spatio-temporal distribution of Prunus cerasifera remains from Eurasia and Northern Africa compiled within the database shown (a) on a topographic map and (b) in an age-longitude plot. Indication of sites mentioned in text and listed chronologically: 353: Sacarovca; 66: Brescia; 38: Aşvan Kale; 1: Aachen-Burtscheid; 116: Ellingen; 58: Berenike; 45: Balalyk Tepe; 53: Bazar-Dara.

3.3.3. Insititia Plum

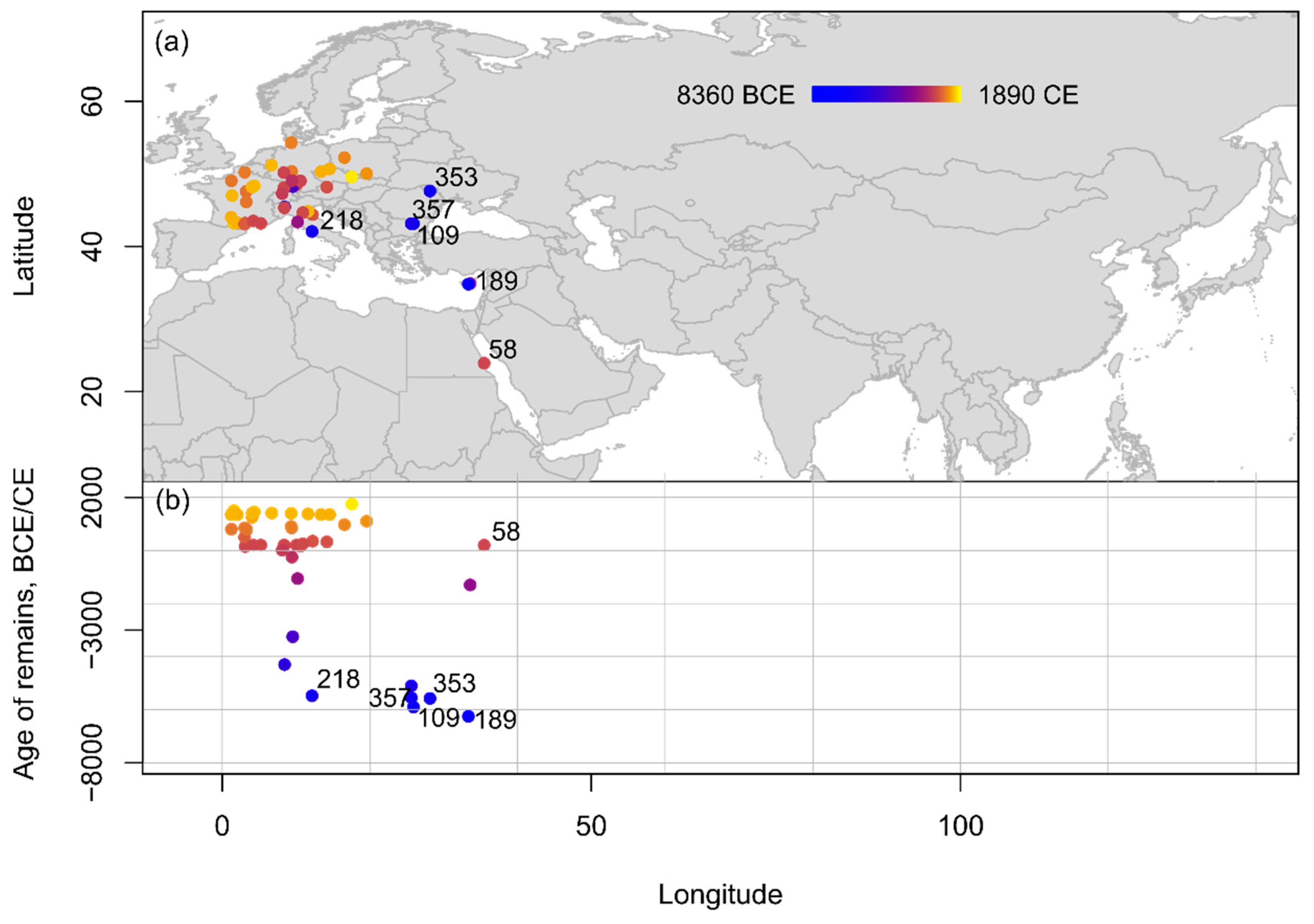

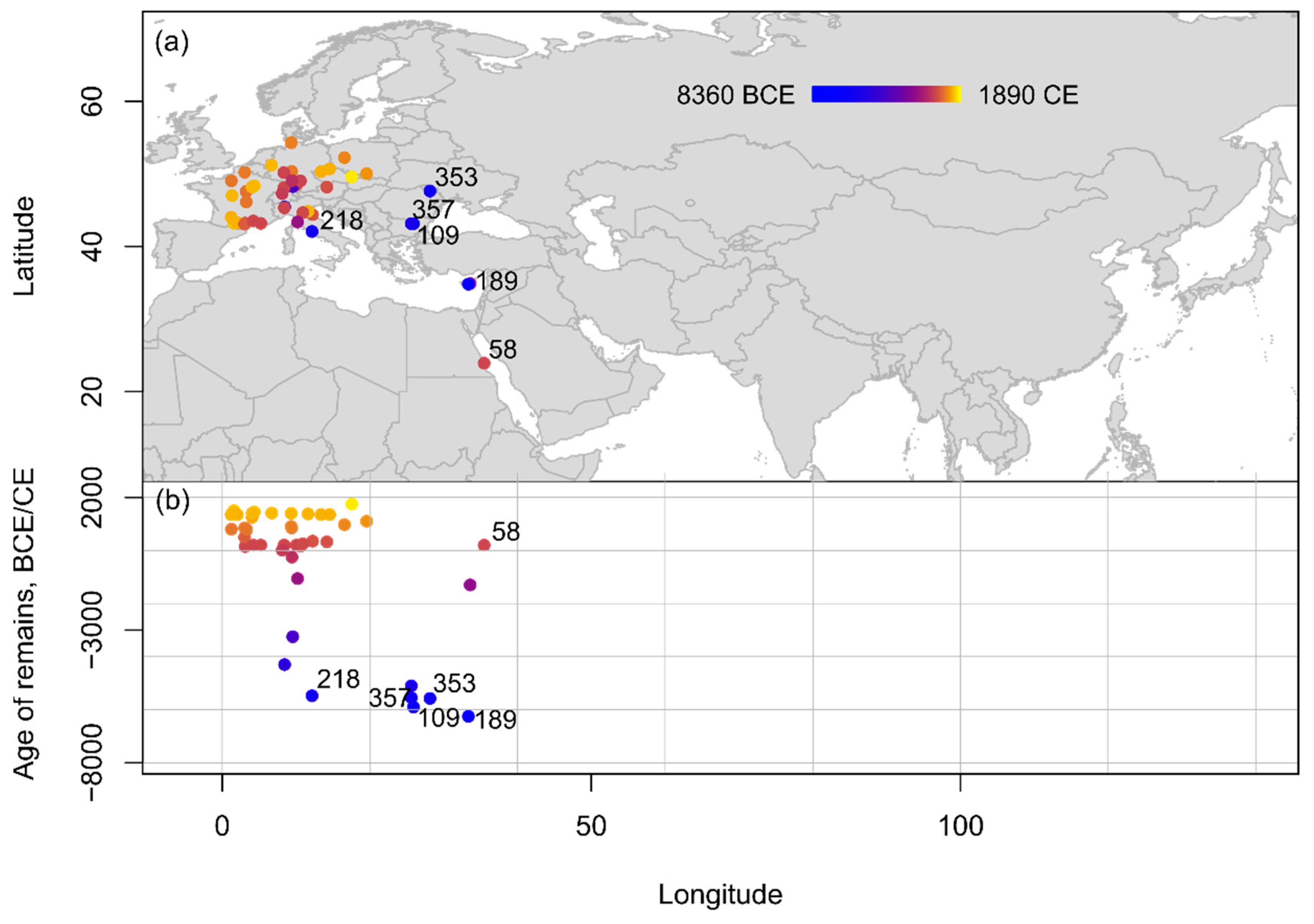

Insititia plum (P. insititia, syn. P. domestica ssp. insititia) finds mostly occur within Europe, with only one example from Northeast Africa at the already mentioned site of Berenike in Egypt (1–400 C.E.) [63], and another from Southwest Asia, where, at present, scholars find the earliest report for this species at the site of Khirokitia in Cyprus (6400–6100 B.C.E.) [66][67][68]. Other early finds, dating to the 6th millennium B.C.E., are attested first from southern and eastern Europe, for example from Dzhulyunitsa and Samovodene in Bulgaria (6100–5700 B.C.E.; 5700–5400 B.C.E., respectively) [69], at the already mentioned site of Sacarovca in Moldova (5650–5500 B.C.E.) [59], and at the site of La Marmotta in Italy (5879–5074 B.C.E.) [56], but reports are generally quite scarce until the beginning of the 1st millennium C.E. A marked increase of insititia plum finds can be attested only from the end of 1st millennium C.E. onward, especially from Central and Northern Europe (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Spatio-temporal distribution of insititia type remains from Eurasia and Northern Africa compiled within the databasegrouped into 1000-year increments shown (a) on a topographic map and (b) in an age-longitude plot. Sites mentioned in text: 189: Khirokitia; 109: Dzhulyunitsa; 353: Sacarovca; 357: Samovodene; 218: La Marmotta; 58: Berenike.

2.3.4. Domestica Plum

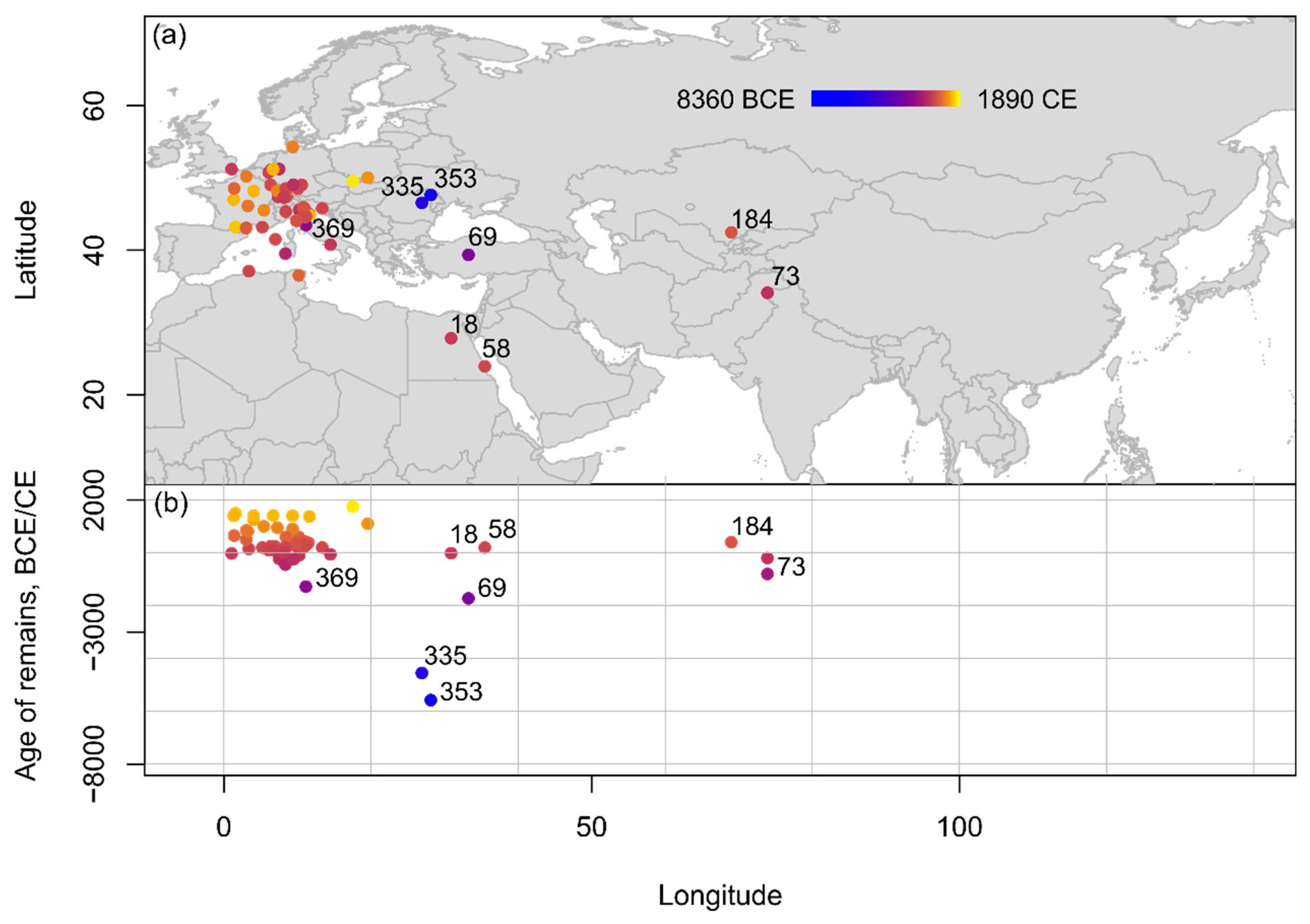

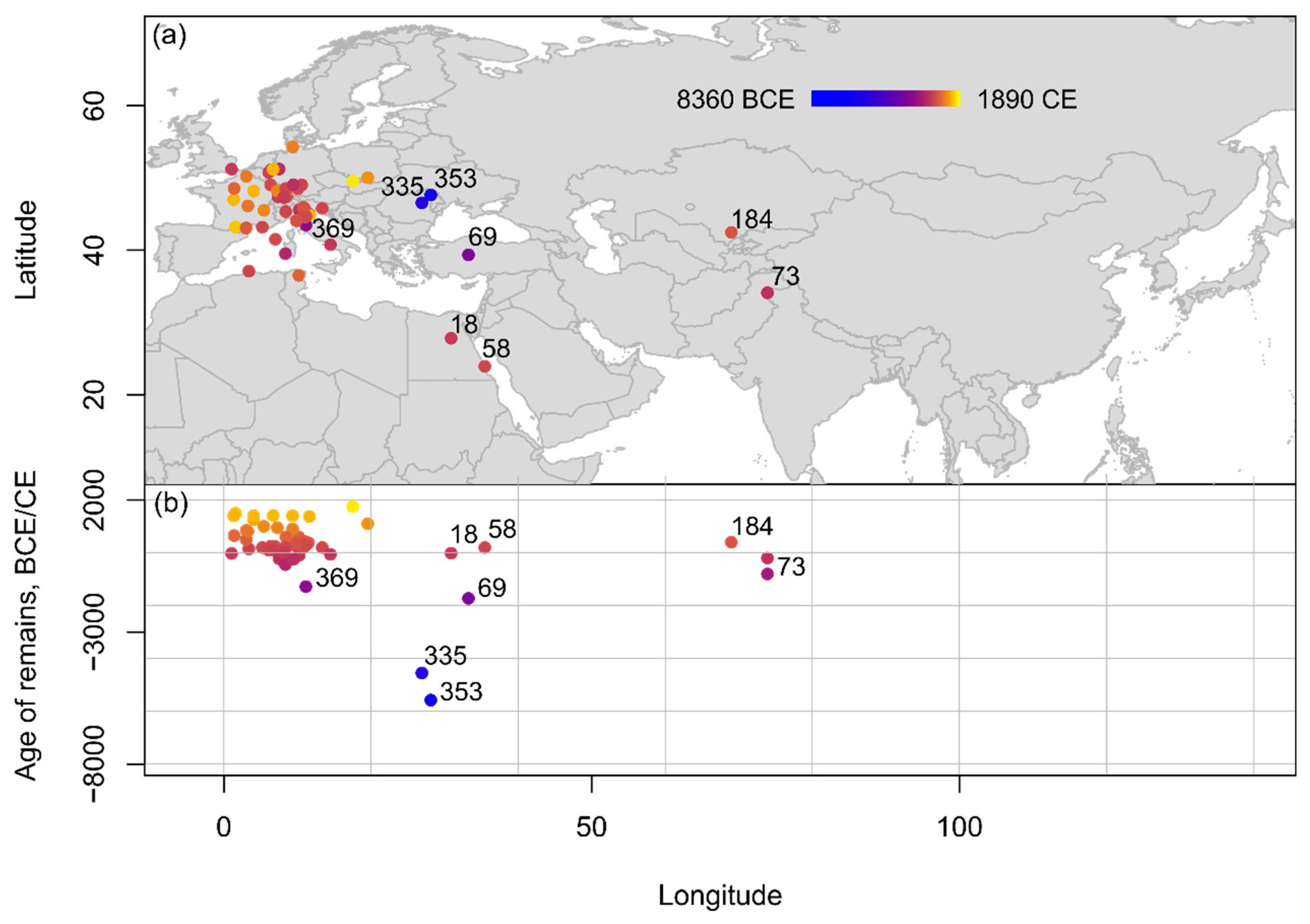

The earliest records of domestica plum (P. domestica, syn. P. domestica ssp. oeconomica, syn. P. domestica spp. domestica) date relatively later than all other species, with the earliest available records coming from 6/5th millennium B.C.E. Europe (Figure 8). As with the earlier insititia and cherry plums, domestica plum has been reported from Sacarovca in Moldova (5650–5500 B.C.E.) [59] and Poduri in Romania (4700–4400 B.C.E.) [70][71]; and subsequently from Scarceta di Manciano in Italy (1443–1116 B.C.E.) [72]. There is only one report of domestica plum in West Asia, from Büklükale in Turkey (c. 1800–1650 B.C.E.) [73], and in Northern Africa, there are two reports of P. domestica from Antinopolis (c. 330 B.C.E.–300 C.E.) [74] and Berenike (1–400 C.E.) [63].

Figure 8. Spatio-temporal distribution of domestica type remains from Eurasia and Northern Africa compiled within the database shown (a) on a topographic map and (b) in an age-longitude plot. Sites mentioned in text and listed chronologically: 353: Sacarovca; 335: Poduri; 369: Scarceta di Manciano; 73: Burzahom; 69: Büklükale; 18: Antipolis; 58: Berenike; 184: Karaspan-tobe.

3. Summary

The rich archaeobotanical record available on finds of large-seeded Prunus fruits, (peaches, apricots, plums, and sloes) across Eurasia and North Africa attest to the continued popularity of this fruit since prehistory. The compilation of large datasets based on the available published records, and metadata studies like the one presented here show the potential of such studies to look for long-term patterns in the use of specific plant species, as well as current limitations.

Peach is the best understood, originating in China, as supported both by genetic and archaeobotanical finds, and spreading to both ends of the Eurasian supercontinent and North Africa by the end of the 1st millennium B.C.E. Looking beyond the peach, the data suggest that: (1) large-fruiting forms of plums existed in Europe prior to the domestication of what we referred to as insititia plum, what most researchers have called P. domestica ssp. insititia, a taxon challenged by recent genetics work; (2) insititia plums are absent outside of Europe, but several Prunus sp. remains from Central Asia, such as those from Togolok and Adju Kui, could be local insititia types or wild relatives; (3) cherry plums (P. cerasifera) are largely absent from the archaeobotanical record of Europe prior to the past three millennia; (4) apricot is largely absent from the archaeobotanical report in Europe, in contrast with written evidence attesting to its presence, at least in Southern Europe from the end of the 1st millennium B.C.E.; (5) the great number of reports simply classified as Prunus sp., or large Prunus stones, attest to the difficulty encountered by archaeobotanists when identifying remains to species level, possibly due to a lack of systematic studies and universally agreed-upon identification criteria. Regardless of the species, there is a visible increase of Prunus stones from all regions starting during the last centuries of the 1st millennium B.C.E.

References

- Fuller, D.Q.; Stevens, C.J. Between domestication and civilization: The role of agriculture and arboriculture in the emergence of the first urban societies. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2019, 28, 263–282.

- Zohary, D.; Hopf, M.; Weiss, E. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin; Oxford University Press on Demand: Oxford, UK, 2012.

- Janick, J. The origins of fruits, fruit growing, and fruit breeding. In Plant Breeding Reviews; Wiley & Sons Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2005; Volume 25, pp. 255–320.

- Gross, B.L.; Olsen, K.M. Genetic perspectives on crop domestication. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 529–537.

- Kislev, M.E.; Hartmann, A.; Bar-Yosef, O. Early domesticated fig in the Jordan Valley. Science 2006, 312, 1372–1374.

- Teskey, B.J. Tree Fruit Production, 3rd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: Westport, CT, USA, 2012; p. 412.

- Bridgeman, T. The Fruit Cultivator’s Manual, Containing Ample Directions for the Cultivation of the Most Important Fruits Including Cranberry, the Fig, and Grape, with Descriptive Lists of the Most Admired Varieties; Bridgeman, T.: New York, NY, USA, 1847.

- Fuller, D.Q. Long and attenuated: Comparative trends in the domestication of tree fruits. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2018, 27, 165–176.

- Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ming, R.; Zhu, S.; Khan, M.A.; Tao, S.; Korban, S.S.; Wang, H. The genome of the pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.). Genome Res. 2013, 23, 396–408.

- Xiang, Y.; Huang, C.-H.; Hu, Y.; Wen, J.; Li, S.; Yi, T.; Chen, H.; Xiang, J.; Ma, H. Evolution of Rosaceae fruit types based on nuclear phylogeny in the context of geological times and genome duplication. Mol. Biol. EVolume 2017, 34, 262–281.

- Cornille, A.; Antolín, F.; Garcia, E.; Vernesi, C.; Fietta, A.; Brinkkemper, O.; Kirleis, W.; Schlumbaum, A.; Roldán-Ruiz, I. A multifaceted overview of apple tree domestication. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 770–782.

- Cornille, A.; Giraud, T.; Smulders, M.J.; Roldán-Ruiz, I.; Gladieux, P. The domestication and evolutionary ecology of apples. Trends Genet. 2014, 30, 57–65.

- Brite, E.B. The origins of the apple in central Asia. J. World Prehistory 2021, 34, 159–193.

- Spengler, R.N. Origins of the apple: The role of megafaunal mutualism in the domestication of Malus and rosaceous trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 617.

- Krussman, G. Manual of Cultivated Broad-Leaved Trees and Shrubs; BT Batsford Ltd.: London, UK, 1986; Volume III.

- Rehder, A. Manual of Cultivated Trees and Shrubs; The Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1947.

- Shi, S.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Yu, J.; Zhou, S. Phylogeny and Classification of Prunus sensu lato (Rosaceae). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2013, 55, 1069–1079.

- Bertsch, K.; Bertsch, F. Geschichte unserer Kulturpflanzen. Anz. Für Schädlingskunde 1948, 21, 16.

- Werneck, H. Die wurzel-und kernechten Stammformen der Pflaumen in Oberösterreich. Nat. Jahrb. Der Stadt Linz. 1961, 7, 7–150.

- Röder, K. Sortenkundliche Untersuchungen an Prunus Domestica; Kiihnarchiv: Berlin, Germany, 1939; Volume 54.

- Domin, K. De origine prunorum diversi generis et fundamenta classificationis botanicae specierum cultarum sectionis Prunophora. Bull. Int. De L’académie Tchéque Des Sci. 1944, 54, 1–31.

- Hegi, G. Illustrierte Flora von Mittel-Europa; 3 Band. Dicotyledones (1 Teil); J. F. Lehmann Verlag: München, Germany, 1906.

- Körber-Grohne, U. Pflaumen, Kirschpflaumen, Schlehen. In Heutige Pflanzen und Ihre Geschichte Seit der Frühzeit; Theiss: Stuttgart, Germany, 1996.

- Watkins, R. Cherry, plum, peach, apricot and almond. Evol. Crop Plants 1976, 1976, 242–247.

- Faust, M.; Surányi, D. Origin and dissemination of plums in. Hortic. Rev. 2010, 23, 179–231.

- Eremin, V. Genetic potentital of species Prunus cerasifera Ehrh and its use in breeding. In ISHS Acta Horticulturae 74: Symposium on Plum Genetics, Breeding and Pomology; ISHS: Leuven, Belgium, 1977; pp. 61–66.

- Zheng, Y.; Crawford, G.W.; Chen, X. Archaeological evidence for peach (Prunus persica) cultivation and domestication in China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106595.

- Hormaza, J.; Yamane, H.; Rodrigo, J. Apricot. In Fruits and Nuts; Chittaranjan, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 171–187.

- Faust, M.; Suranyi, D.; Nyujto, F. Origin and dissemination of apricot. Hortic. Rev.-Westport N. Y. 1998, 22, 225–260.

- Faust, M.; Timon, B. Origin and dissemination of peach. Hortic. Rev. 2010, 17, 331–379.

- Jiang, H.; Yang, J.; Liang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Qi, X.; Sheng, P. Palaeoethnobotanical analysis of plant remains discovered in the graveyard of the Haihun Marquis, Nanchang, China. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2021, 30, 119–135.

- Wilkinson, K.N.; Gasparian, B.; Pinhasi, R.; Avetisyan, P.; Hovsepyan, R.; Zardaryan, D.; Areshian, G.E.; Bar-Oz, G.; Smith, A. Areni-1 Cave, Armenia: A Chalcolithic–Early Bronze Age settlement and ritual site in the southern Caucasus. J. Field Archaeol. 2012, 37, 20–33.

- Smith, A.; Bagoyan, T.; Gabrielyan, I.; Pinhasi, R.; Gasparyan, B. Late chalcolithic and medieval archaeobotanical remains from Areni-1 (Birds’ Cave), Armenia. Gasparyan Arimura 2014, 2014, 233–260.

- Robbeets, M.; Bouckaert, R.; Conte, M.; Savelyev, A.; Li, T.; An, D.-I.; Shinoda, K.-i.; Cui, Y.; Kawashima, T.; Kim, G. Triangulation supports agricultural spread of the Transeurasian languages. Nature 2021, 599, 616–621.

- Crawford, G.W. Plant domestication in East Asia. In Handbook of East and Southeast Asian Archaeology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 421–435.

- Doshisha University, D.O.A. Ikiriki iseki ; Tarami-chō Board of Education: Nagasaki, Japan, 1986.

- Lone, F.A.; Khan, M.; Buth, G.M. Palaeoethnobotany: Plants and Ancient Man in Kashmir; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020.

- Aali, A.; RÜHLI, F.; Abar, A.; STÖLLNER, T. The salt men of Iran: The salt mine of Douzlakh, Chehrabad. Archäologisches Korresp. 2012, 42, 61–81.

- Kučan, D. Zur ernährung und dem gebrauch von pflanzen im Heraion von Samos im 7. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Jahrb. Des Dtsch. Archäologischen Inst. 1995, 110, 1–64.

- Kučan, D. Rapport synthétique sur les recherches archéobotaniques dans le sanctuaire d’Héra de l’île de Samos . Pallas 2000, 99–108, I–IV.

- Alonso Martinez, N. Agriculture and food from the Roman to the Islamic Period in the North-East of the Iberian peninsula: Archaeobotanical studies in the city of Lleida (Catalonia, Spain). Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2005, 14, 341–361.

- Murphy, C.; Thompson, G.; Fuller, D.Q. Roman food refuse: Urban archaeobotany in Pompeii, Regio VI, Insula 1. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2013, 22, 409–419.

- Zech-Matterne, V.; Tengberg, M.; Van Andringa, W. Sesamum indicum L. (sesame) in 2nd century BC Pompeii, southwest Italy, and a review of early sesame finds in Asia and Europe. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2015, 24, 673–681.

- Bosi, G.; Castiglioni, E.; Rinaldi, R.; Mazzanti, M.; Marchesini, M.; Rottoli, M. Archaeobotanical evidence of food plants in Northern Italy during the Roman period. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2020, 29, 681–697.

- Zheng, Y.; Jiang, L.J.Z. A study of ancient rice unearthed from Kuahuqiao. Zhongguo Shuidao Kexue 2004, 18, 119–124. (In Chinese)

- Fuller, D.Q.; Harvey, E.; Qin, L. Presumed domestication? Evidence for wild rice cultivation and domestication in the fifth millennium BC of the Lower Yangtze region. Antiquity 2007, 81, 316–331.

- Stevens, C.J.; Murphy, C.; Roberts, R.; Lucas, L.; Silva, F.; Fuller, D.Q. Between China and South Asia: A Middle Asian corridor of crop dispersal and agricultural innovation in the Bronze Age. Holocene 2016, 26, 1541–1555.

- Shelach-Lavi, G.; Teng, M.; Goldsmith, Y.; Wachtel, I.; Stevens, C.J.; Marder, O.; Wan, X.; Wu, X.; Tu, D.; Shavit, R. Sedentism and plant cultivation in northeast China emerged during affluent conditions. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218751.

- Akita, P.B.O.E. Tetori-Shimizu Iseki; Akita Prefecture: Akita, Japan, 1990.

- Jiang, H.-E.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Lü, E.-G.; Li, C.-S. A consideration of the involucre remains of Coix lacryma-jobi L. (Poaceae) in the Sampula Cemetery (2000 years BP), Xinjiang, China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 1311–1316.

- Jiang, H.-E.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Li, X.; Yao, Y.-F.; Ferguson, D.K.; Lü, E.-G.; Li, C.-S. Evidence for early viticulture in China: Proof of a grapevine (Vitis vinifera L., Vitaceae) in the Yanghai Tombs, Xinjiang. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 1458–1465.

- XUARM & XIA (Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Museum, X.I.O.A.). Sampula in Xinjiang of China–Revelation and Study of Ancient Khotan Civilization; (in Chinese with English Abstract); Xinjiang People’s Publishing House: Urumchi, China, 2001.

- Kotzamani, G.; Livarda, A. People and plant entanglements at the dawn of agricultural practice in Greece. An analysis of the Mesolithic and early Neolithic archaeobotanical remains. Quat. Int. 2018, 496, 80–101.

- van Zeist, W.; Bottema, S. Plant husbandry in early neolithic Nea Nikomedeia, Greece. Acta Bot. Neerl. 1971, 20, 524–538.

- Rottoli, M. Un nuovo frumento vestito nei siti neolitici del Friuli-Venezia Giulia (Italia nord orientale). Gortania 2005, 26, 67–78.

- Rottoli, M.; Castiglioni, E. Prehistory of plant growing and collecting in northern Italy, based on seed remains from the early Neolithic to the Chalcolithic (c. 5600–2100 cal BC). Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2009, 18, 91–103.

- Sarigu, M. Man, Plant Remains, Diet: Spread and Ecology of Prunus L. in Sardinia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cagliary, Cagliari, Italy, 2016.

- Antolín, F.; Jacomet, S. Wild fruit use among early farmers in the Neolithic (5400–2300 cal BC) in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula: An intensive practice? Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2015, 24, 19–33.

- Kuzminova, V.; Dergacev, A.; Larina, O. Aleoetnobotaniceskie issledovanija na poselenii Sakarovka I. Rev. Arheol. 1998, 2, 170–171.

- Nesbitt, M.; Bates, J.; Mitchell, S.; Hillman, G. The Archaeobotany of Aşvan Environment and Cultivation in Eastern Anatolia from the Chalcolithic to the Medieval Period; British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara: Ankara, Turkey, 2017.

- Knörzer, K.-H. Römerzeitliche Pflanzenfunde aus Aachen-Burtscheid. Archaeo-Physika 1980, 7, 35–60.

- Frank, K.-S.; Stika, H.-P. Bearbeitung der Makroskopischen Pflanzen-und Einiger Tierreste des Römerkastells Sablonetum (Ellingen bei Weissenburg in Bayern); Verlag Michael Lassleben: Kallmünz, Germany, 1988.

- Cappers, R.T. Roman Foodprints at Berenike: Archaeobotanical Evidence of Subsistence and Trade in the Eastern Desert of Egypt; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; Volume 55.

- Al’baum, L. Балалык-Тепе (Balalyk-Tepe); Akadmiia Nayk UzSSR: Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 1960.

- Bubnova, M. К Вoпрoсу o Земледелии На Западнoм Памире В IX-XI вв (Regarding the question of agriculture in the Western Pamirs from the IX–XI centuries). In Прoшлoе Средней Азии: Археoлoгия, Нумизматика и Эпиграфика, Этнoграфния (Past Central Asia: Numismatics Archaeology and Ethnography Epigraphy); Издательствo–Дoниш (Publisher–Donish): Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 1987; pp. 59–66.

- Waines, J.G.; Price, N.S. Plant remains from Khirokitia in Cyprus. Paléorient 1975, 3, 281–284.

- Miller, N. Some plant remains from Khirokitia, Cyprus: 1977 and 1978 excavations. Fouill. Récentes À Khirokitia 1977, 1981, 183–188.

- Hansen, J.M. Khirokitia Plant Remains: Preliminary Report (1986, 1988–1990). In Le Brun, A. (ed) Fouilles Recents à Khirokitia, Chypre, 1983–1986. Etudes Néolithiques. Ed. Rech. Sur Les Civilisations. Mem. 1989, 41, 235–250.

- Marinova, E.; Krauß, R. Archaeobotanical evidence on the Neolithisation of Northeast Bulgaria in the Balkan-Anatolian context: Chronological framework, plant economy and land use: Археoбoтанични свидетелства за неoлитизацията на Северoизтoчна България в Балканo-Анатoлийски кoнтекст: Хрoнoлoгия, изпoлзване на растителните видoве и земята. Bulg. e-J. Archaeol. Българскo Е-Списание За Археoлoгия 2014, 4, 179–194.

- Monah, D.; de Istorie, P.N.M. Poduri-Dealul Ghindaru: O Troie în Subcarpaţii Moldovei; Muzeul de Istorie Piatra Neamț: Piatra Neamț, Romania, 2003.

- Bejenaru, L.; Bodi, G.; Stanc, S.; Danu, M. Middle Holocene subsistence east of the Romanian Carpathians: Bioarchaeological data from the Chalcolithic site of Poduri-Dealul Ghindaru. Holocene 2018, 28, 1653–1663.

- Bellini, C.; Mariotti-Lippi, M.; Mori Secci, M.; Aranguren, B.; Perazzi, P. Plant gathering and cultivation in prehistoric Tuscany (Italy). Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2008, 17, 103–112.

- Fairbairn, A.S.; Wright, N.J.; Weeden, M.; Barjamovic, G.; Matsumura, K.; Rasch, R. Ceremonial plant consumption at Middle Bronze Age Büklükale, Kırıkkale Province, central Turkey. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2019, 28, 327–346.

- Smith, W. Archaeobotanical Investigations of Agriculture at Late Antique Kom el-Nana, Tell el-Amarna: Egypt Exploration Society Excavation Memoir 70; Egypt Exploration Society: London, UK, 2003.

More

Information

Subjects:

Archaeology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.7K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

09 May 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No