Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xiaogang Li | -- | 3854 | 2023-05-05 19:31:02 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 3854 | 2023-05-06 03:24:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Samarpita, S.; Li, X. Leveraging Exosomes against Th17 Cell Catastrophe. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43896 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Samarpita S, Li X. Leveraging Exosomes against Th17 Cell Catastrophe. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43896. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Samarpita, Snigdha, Xiaogang Li. "Leveraging Exosomes against Th17 Cell Catastrophe" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43896 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Samarpita, S., & Li, X. (2023, May 05). Leveraging Exosomes against Th17 Cell Catastrophe. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43896

Samarpita, Snigdha and Xiaogang Li. "Leveraging Exosomes against Th17 Cell Catastrophe." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 May, 2023.

Copy Citation

Exosomes are membrane-bound extracellular vesicles that can act as biological messengers between cells, in the context of health and disease. In comparison to several lab-based drug carriers, exosome exhibits high stability, accommodates diverse cargo loads, elicits low immunogenicity and toxicity, and therefore manifests tremendous perspectives in the development of therapeutics. The efforts made to spur exosomes in drugging the untreatable targets are encouraging. T helper (Th) 17 cells are considered the most prominent factor in the establishment of autoimmunity and several genetic disorders.

exosome engineering

Th17 cell

drug delivery vector

1. Introduction

The advancement of novel computational tools and approaches, such as computer-aided drug design, high-throughput screening and artificial intelligence, helps expedite drug discovery and identify an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) as new lead compounds in several disease settings [1]. Howbeit, several drugs escape from reaching the target sites due to an individual’s biological barrier and immune defense mechanisms during the process of disease treatment. Moreover, unwanted toxicities due to their accumulation in off-target tissues have been a major bottleneck in their translation into clinics [2][3]. Thereupon, strategies that enhance tissue-specific drug delivery hold promise to overcome these limitations and demonstrate tremendous success in parallel with drug discovery.

Exosomes are exemplified as “membrane-anchored extracellular vesicles” derived from the endosomal compartment of almost all eukaryotic cells [4]. As a nanoscale-sized vesicle, exosomes are found in all biological fluids (urine, blood, saliva, semen, breast milk and cerebrospinal fluid), which fabricate them as an excellent biomarker in the diagnosis of cancer and related disorders [5]. At the forefront, the exosome adapts a specific mechanism that includes surface receptor-mediated endocytosis, pinocytosis and membrane fusion to transport cargo to recipient cells [6]. As exosomes are imprinted with the ability to facilitate cell–cell communication, it is an unbiased claim that they represent potent drug delivery vectors in clinics due to their characteristic properties of innate stability, low immunogenicity, negative zeta potential to escape the immune attack and good capacity to penetrate through biological barriers [7].

Exosomes are extensively explored as tools in the landscape of immune regulation and immunotherapies, harnessing their role in immune surveillance, antigen presentation, immunosuppression, and anti-tumor immunity [8]. Proteomic studies have demonstrated that exosomes are tagged with immune function-related proteins, such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-1, β2-microglobulin and sub-units of the T cell receptor (TCR)-CD3 complex, thus defining their essential involvement in immune regulation [9]. For instance, cancer cell-derived exosomes activate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling in endothelial cells and advance angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment [10]. In addition, exosomes exhibit immunosuppressive function via inhibition of CD8+ T cells, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) secretion and expansion of suppressive regulatory T cells [11][12]. Notwithstanding, exosomes in the synovial fluid encapsulate citrullinated proteins that promote the formation of auto-immunogenic determinants [13]. However, dendritic cells (DCs)-derived exosomes express major histocompatibility complex class (MHC)-I molecules, which contribute to antigen presentation and anti-tumor responses [14], making them a hopeful prospect from the therapeutic standpoint of exosomes. Thereupon, the engineering of exosomes to deliver peptides, vaccines or drugs into specific cells in a time-dependent manner can be a star therapeutic strategy to negotiate immune responses with regard to immune-related diseases.

In various diseases such as cancer, autoimmune diseases and most genetic disorders, there exists an intricate imbalance between the occurrence of inflammatory events and the suppression of inflammation, which instigates disease progression [15]. Of note, immune cells are important modulators that facilitate this imbalance. In this context, an increased frequency of Th17 cells, a subset of CD4+ T immune cells, has been studied to promote the initiation and development of several tumors and autoimmune/inflammatory disorders via distinct mechanisms [16][17]. Thus far, targeting Th17 cells is an unmet clinical need. At present, exosome-based immune therapy is a jackpot as an effective strategy to restore immune balance and halt disease pathogenesis. In cancer, for example, curcumin export by exosomes facilitates the differentiation of effector T cells to kill cancer cells [18].

2. The Structure of Exosomes and Its Composition

Exosomes are defined as lipid-bilayered extracellular vesicles with a diameter ranging from 30 to 200 nm. Secreted naturally from almost all kinds of cells, these vesicles are formed through endosomal membrane budding and constitute the nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates and lipids of a cell [19]. Moreover, these nanosized biological vectors shuttle cell-derived nucleic acids, lipids and proteins as signaling molecules to facilitate signal transduction and communication between neighboring cells [19]. Previous researchers have demonstrated that exosomes are closely associated with viral responses, immune regulation, cardiovascular risks, central nervous system (CNS) disorders, pregnancy, cancer and autoimmune disease progression [4]. Numerous efforts are in progress to isolate circulating exosomes that import biological substances and dynamically expand them as biomarkers as they can manifest several pathophysiological conditions [20]. Emphatically, exosomes have been explored as drug delivery vectors due to their ability to inherit characteristic properties of a cell and exhibit a better safety profile as compared to cell-based therapy [21]. Instead, molecular insights to understand the structures of exosomes could be helpful to engineer exosomes for loading cargoes to ferry them into target cells/tissues.

The contents inside and on the surface of the exosomes mirror the configuration of the parent cell. However, irrespective of their parental origin, some features including tetraspanins (CD9, CD81, CD82 and CD63), syndecans, heat shock proteins (Hsp60, Hsp20, Hsp70, Hsp22, Hsp90 and alpha-B Crystallin), biogenesis-associated proteins (ESCRT proteins, CHMP4, TSG101, STAM1, VPS4, PLD2), membrane transport and fusion proteins (annexins, GTPases, and Rab molecules), nuclear acids (long non-coding RNAs, miRNA, mRNA and DNA) and lipids, commonly span the membrane of exosomes structure [22]. Tetraspanins are abundant on the exosomal membranes to form a complex with integrins and contribute to the tropism of exosomes [23]. Advanced proteomic studies revealed that heat shock, transport and fusion proteins mediate the sprouting of multicellular vesicular bodies (MVBs) [24], whereas the lipidomic data demonstrated that the lipid contents of exosomes are either conserved or relatively similar and are crucially involved in preserving the shape of exosomes and maintaining homeostasis in the recipient cells [25]. Moreover, the asymmetrical distribution of the lipid bilayer of exosomes allows for successful drug delivery. For example, exosomes that display α6β4 integrins are likely to target S100-A4 positive fibroblasts and surfactant protein C (SPC)-positive epithelial cells of the lungs [26]. Similarly, lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1)-tagged exosomes act as a “molecular Trojan horse” that can cross the blood–brain barrier to treat central nervous system (CNS)-related disorders [27], and αvβ6 exosomes play a critical role in interstitial inflammation and fibrosis [28].

The membrane of the exosomes is composed on the basis of their origin and physiological environment during exosome biogenesis [4]. Accordingly, the target site depends on the differential expression of markers on the surface of exosomes [29]. As a proof of concept, exosomes derived from dendritic cells express MHC class I, MHC class II, ICAM, CD40 and CD86 [30]. Also, chimeric antigen receptor T cell immunotherapy (CAR-T) cell-based exosomes express CARs and contain cytotoxic molecules used for cancer therapy [31], and those released by natural killer (NK) cells express lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) and DNAX accessory molecule 1 (DNAM-1) [32], thus, mirroring the characteristic features of parent cells. Exosomes generated from γδ T cells carry death-inducing ligands (FasL and TRAIL) and CD80/86 and MHC class I/II with dual tumor-killing effects [33]. Information on the membrane structures of exosomes that can guide their destination is available in different web-based sources, including the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles, American Society for Exosomes and Microvesicles, Extracellular RNA Communication Program, ExoCarta, Vesiclepedia and EVpedia.

3. Mechanistic Insights into Exosome Biogenesis and Release

The biogenesis of exosomes begins with the formation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) that develop via inward budding of the plasma membrane (early endosomes), which then generate late endosomes composed of combined intraluminal vesicles (ILVs), in a clathrin- or caveolin-dependent or -independent manner, called multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [19]. Based on the pathway they follow, they are categorized as degradative multivesicular exosomes (MVE) which coalesce with the lysosomes to ensure degradation of intraluminal contents and secretory MVE, which pinches out of the membrane to discharge its contents into the extracellular space. Moreover, MVE also leads to the formation of endosomal-related organelle, melanosomes and Weibel–Palade bodies in pigment and endothelial cells, respectively.

The biogenesis and protein sorting of ILVs are tightly regulated processes requiring an endosomal sorting complex (ESCRT) or can be an independent process [19]. In the context of the ESCRT-dependent pathway, it is composed of ESCRT-0, ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II and ESCRT-III complexes and AAA ATPase VPS4, tumor susceptibility gene (Tsg101) and ALIX auxiliary proteins [34]. EXCRT-0 escorts mono-ubiquitinated proteins into the endosomal domain with the help of cytosolic protein hepatocyte responsive serum phosphoprotein (HRS) heterodimer, signal transducing adapter molecule (STAM)1/2, Eps15 and clathrin. In the next sequential step, ESCRT-I and ESCRT-II together with ESCRT-0 bind to ubiquitinated cargo with higher affinity to form a stable membrane neck. Finally, ESCRT-III assembles the complex for the excision of the membrane neck and internalization of buds into the endosomes. Eventually, the cargoes are de-ubiquitinated by de-ubiquitylating enzymes and, ATPase VPS4 dissociates and recycles the endosomal components for the next cycle [34]. However, if de-ubiquitination is restrained, ILVs are subjected to lysosomal degradation [35]. Alternatively, the marker protein of exosomes, Alix, binds to ESCRT-III and guides the un-ubiquitinated cargo to the ILVs [34][35]. Besides it, the ESCRT-independent mechanism occurs via the melanosomal protein Pmel17 in melanocytes [36]. The association of the luminal domains of Pmel17 along with lipids contributes to ILV formation. It has also been reported that tetraspanin mediates cargo sorting and exosome secretion in an ESCRT-independent manner [37]. For instance, tetraspanin CD63 helps the loading of pigment cell-specific protein 17 into the ILV during the synthesis of the melanosome [37]. Similarly, the loading of MHC-II occurs exclusively in tetraspanin CD9-enriched membrane domains [38]. In addition, as reported previously, ceramide-rich parts of endosomes are prone to inward invagination, and hence, defects in the conversion of sphingomyelin into ceramide by sphingomyelinase (SMase) abrogates ILV formation, wherein, cholesterol is necessary for the formation of curved membrane structures called caveolae [39]. This has been confirmed for lipid-based cargo sorting as well as exosome secretion. It is imperative to understand that the absence of ESCRT machinery did not hamper the MVB formation, but instead manipulated ILV number and size, thus exemplifying coordination between ESCRT-dependent and -independent pathways during exosome biogenesis.

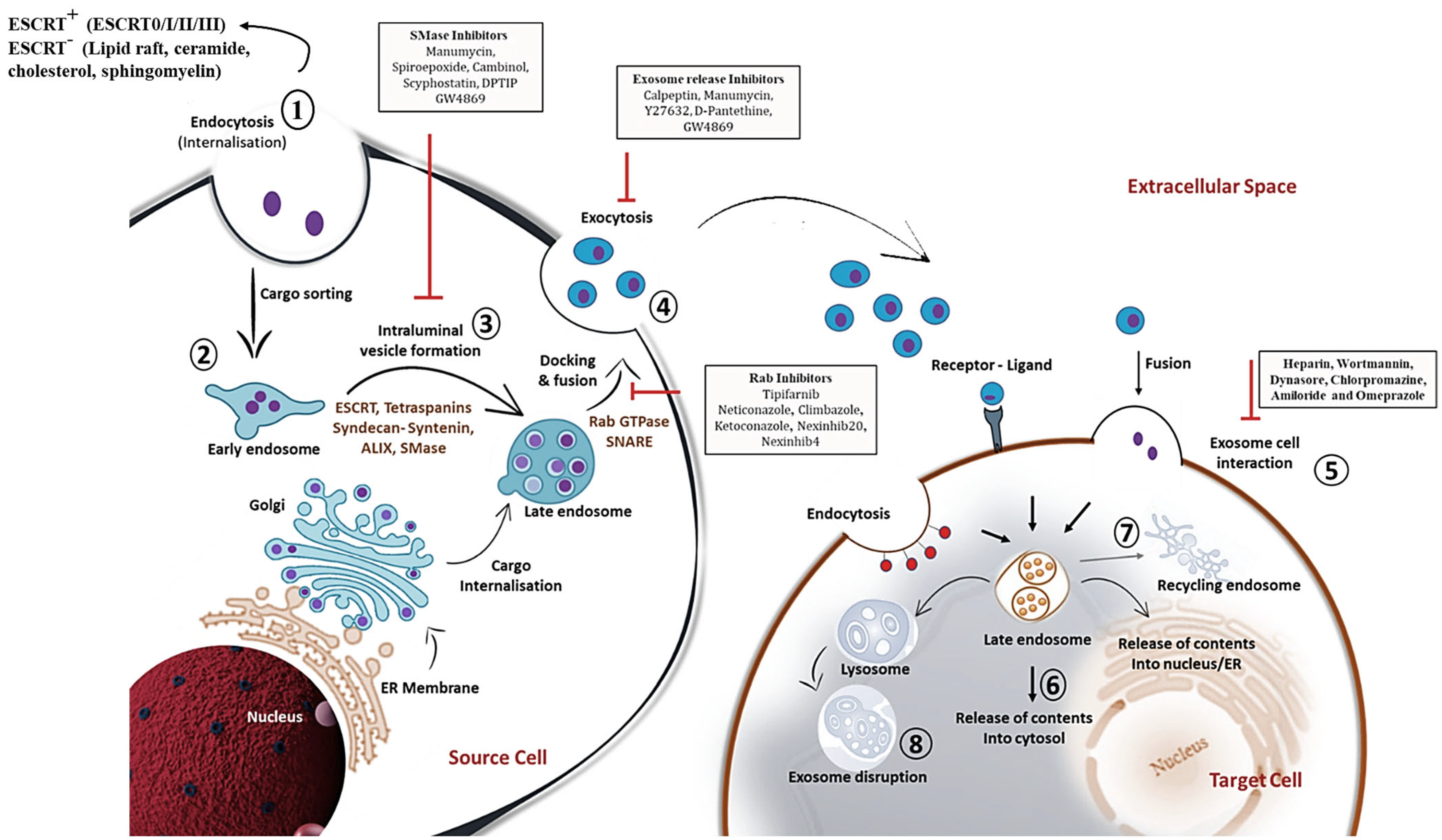

In view of exosome release, the involvement of molecular switches and motors (small GTPase, dynein and kinesin), cytoskeletal elements (microtubule and microfilaments) and membrane fusion complexes (SNARE complex) has been made crystal clear [40]. Rab GTPases control the trafficking and fusion of MVB with the plasma membrane. During the transport of MVB, the microtubule cytoskeleton and molecular motors direct its polarized distribution in the cells [40]. Rightly, the soluble N-ethylmaleimide (NEM)-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex is a core protein complex that assists membrane fusion and secretion [41]. Descriptively, the fusion process is initiated through the interaction of the plasma membrane protein syntaxin with synaptotagmin, the calcium sensor located on MVBs. Then, v-SNAREs of MVBs pair with the t-SNAREs, thus driving SNARE complex formation and fusion of membranes to release exosomes to the outer environment [40][41] (Figure 1). Further understanding of the complex process of exosome biogenesis should pave the way for novel therapeutic avenues.

Figure 1. Detailed schematic overview of exosome biogenesis and inhibitors that block the release of exosomes within the endosomal system. The formation of exosomes involves the inward budding and fusion of the limiting membrane of endocytic vesicles that engender intraluminal vesicles (ILVs). The maturation process of ILVs can be through endosomal complexes required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent and -independent mechanisms that process cargo sorting and formation of multivesicular bodies (MVBs). Components of MVBs can then be integrated into the membranes for release into the extracellular space or may be guided for lysosomal degradation. Exosomal contents released into the extracellular space can then be internalized by the target cell via membrane fusion, ligand-receptor conformation or endocytosis mechanism. This illustration further comprehends various chemical inhibitors, including SMase inhibitors, exosome release inhibitors and Rab inhibitors (depicted in black rectangular boxes) that prevent exosome biogenesis and secretion within the endosomal compartment. The sequential steps on exosome biogenesis follows: 1. Exosome formation; 2. Cargo sorting; 3. MVBs formation; 4. Exosome release; 5. Exosome-target cell interaction; 6. Cargo release into cytosol of target cells; 7. MVBs endosome recycling; and 8. Lysosome degradation of exosomes. Abbreviations: Rab; Ras associated binding protein, SNARE; SNAP receptor.

With much detailed apprehension on the biogenesis of exosomes, efforts are in progress to inhibit the production or release of an exosome subpopulation that is involved in the pathology. Nevertheless, the available inhibitors are listed in Figure 1.

4. Exosome Classification and Its Biodistribution: Current State-of-the-Art

At least two distinct sub-types of exosomes have been discovered based on their modifications—natural exosomes and bioengineered exosomes. Subsequently, natural exosomes are subdivided into animal-derived exosomes and plant-derived exosomes based on their parental sources. With reference to animal-derived exosomes, almost all normal cells such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, T and B immune cells and umbilical cord endothelial cells produce exosomes. Also, normal exosomes are plentily available in biofluids, such as plasma, urine, milk and saliva. In essence, tumor-cell-derived exosomes, because of their specific expression of tetraspanins, have also been considered for the delivery of chemotherapeutic or anti-cancer drugs. However, tetraspanins can sometimes lead to tumor growth and an increase in metastasis in certain types of cancer [42]. Therefore, the alarming risk associated with tumor exosomes jeopardizes the suitable therapeutic effects and aggravates patients’ malignancies, thus providing an awakening call to weigh the benefit-to-risk ratio and choose the right exosomes for therapy purposes. Based on these perspectives, several plant-derived exosomes have been explored for clinical use, as they are derived from purified sources and are considerably safe [43]. Contrastingly, engineered exosomes fall under the category of exosomes that are surface modified and loaded with substances to efficiently target disease sites and negate adverse profiles associated with treatments. With no available information to date, further sub-divisions of exosomes based on organophilicity, biodistribution and clearance may be considered [42][43].

Irrespective of the parental origin, it has been stated that the exosomes are largely accumulated in the liver, spleen, kidney and lungs. However, there is evidence that states that exosomes have asymmetric biodistribution based on their parental cell and the route of administration. Like, glioma-derived exosomes are demonstrated to efficiently deliver the drug to the brain [44]. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes preferentially target kidneys in patients with kidney disorders [45]. Besides the exosome origin being one of the striking reasons, the route of administration can also be equally considered to alter exosome biodistribution. For instance, intramuscular administration of exosomes increases their bioavailability in the gastrointestinal tract. Alternatively, the oral gavage method of administration localized it more in the intestine. However, the most common method of administration is intravenous, in which exosomes travel via the heart and are entrapped in the capillaries of the lungs [46]. This highlights that the method of administration can lead to extreme variability and an asymmetric biodistribution pattern for exosomes.

5. Exosome in Diseases: The Boon against Evil

Capitalizing on the role of exosomes in the progression or treatment of several diseases is an important aspect of this research. Earlier described as “waste disposal units”, exosomes are now a hot research topic as they proportionately function between physiological and several pathological states. Finding how exosomes communicate with or affect neighboring/distant cells may provide insights into their roles in disease regulation, exploit them for drug delivery or monitor disease state in a non-invasive procedure.

Investigating the darker side of the exosome reveals that it secretes β-amyloid and hyperphosphorylated, misfolded tau into the extracellular space and leads to the pathological spreading of tauopathy in Alzheimer’s patients [47]. Exosomal alpha-synuclein (α-syn) promotes the aggregation of misfolded α-syn, a phenotype predominant in Parkinson’s disease [48]. An increase in the levels of circulating exosomes loaded with pro-inflammatory cytokines leads to persistent inflammation, as has been reported in multiple sclerosis and autoimmune encephalomyelitis [49]. In autoimmune rheumatoid arthritis (RA), exosomes derived from synovial fibroblasts and serum-induced Th17 differentiation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines aggravate disease conditions [50]. In genetic diseases such as autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), cystic cells and urinary exosomes promote cyst growth in ADPKD patients [51]. In addition, fibroblasts of breast cancer origin secrete exosomes that mediate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis via altered expression of lncRNA. A detailed analysis of miRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs and proteins that promote several diseases has been categorized in Table 1.

Table 1. List of exosomal RNAs in the occurrence of disease.

| Exosome Source | Exosome Cargo |

Disease | Disease Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCT116 and Serum | miR-25, miR-130b and miR-425 | Colorectal Cancer | Aggravates liver metastasis | [52] |

| Serum | miR-1247-3p | Liver cancer | Promotes lung metastasis | [52] |

| A2780 CCM | miR-223 | Epithelial ovarian cancer | Promotes chemoresistance | [52] |

| Variable | miR-21 | Multiple cancers | Promotes cancer | [52] |

| Serum | miR-7977 | Lung adenocarcinoma | Increase in proliferation, invasion and inhibits apoptosis | [52] |

| Pan02 CCM | miR-155-5p and miR-221-5p | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Promotes metastasis | [52] |

| HT-29/SW480 | miR-375-3p | Colon cancer | Induces EMT | [52] |

| MSC | miR-21-5p | Breast cancer | Promotes chemoresistance | [52] |

| Plasma | miR-1-3p | Sepsis | Endothelial cell dysfunction | [52] |

| Serum | miR-4449 | Diabetic kidney | Promotes pro-inflammation & oxidative stress | [53] |

| MGC803, MKN45, HGC27, and SGC7901 CCM | miR-21-5p | Gastric cancer | Promotes peritoneal metastasis | [54] |

| Human bronchial epithelial cells | miR-21 and miR-210 | COPD | Promotes myofibroblast differentiation and hypoxia | [55] |

| Serum | miR-96, miR-222-3p, miR-499a-5p | Lung cancer | Promote cell migration and invasion | [55] |

| Induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSC)-derived astrocytes/microglia | miR-21-5p | Adenocarcinoma | Induce neurotoxic reactive astrocytosis, cognitive impairment | [56] |

| TDEs | miR-141 | Lung cancer | Induces angiogenesis and malignancy | [57] |

| TDEs | miR-107 | Gastric Cancer | Promote immunosuppression | [58] |

| SCLC | miR-375-3p | Lung Cancer | Disrupts vascular barrier | [59] |

| Urine | miR-200b | Renal fibrosis | Fibrosis progression | [60] |

| Plasma | lnc-MKRN2 | Parkinson Disease | Develops disease occurrence | [52] |

| Serum | lncRNA-UCA1 | Pancreatic Cancer | Promotes angiogenesis | [52] |

| Serum | HOXD-AS1 | Prostate Cancer | Promotes metastasis | [52] |

| Urine | lncBCYRN1, lncLNMAT2 | Bladder Cancer | Promotes lymphatic metastasis | [52] |

| CCM | LncPCGEM1 | Gastric cancer | Induces metastasis and migration | [52] |

| TGF-β A549 | lnc-MMP2-2 | Lung cancer | Promotes invasion and metastasis | [55] |

| A172 cells | POU3F3 | Glioma | Promotes angiogenesis | [61] |

| CAF | MEG3 | SCLC | Cisplatin resistance | [62] |

| MCF7 | MALAT1 | Breast cancer | Promotes proliferation | [63] |

| Plasma | circ-RanGAP1 | Gastric cancer | Promotes metastasis | [52] |

| HCC CCM | circ-RNA-100338 | HCC | Promotes angiogenesis and invasion | [52] |

| Serum | Circ-0006156 | Thyroid cancer | Promotes tumorigenesis | [52] |

| TDEs | PDE8A | Pancreatic cancer | Elevates invasive growth | [64] |

| L-02 CCM | circ-100284 | Hepatocarcinoma | Accelerates cell cycle and proliferation | [65] |

Abbreviations: HCT, Human colorectal cancer cell line; CCM, Cell culture media; EMT, Epithelial to mesenchymal transition; MSC, Mesenchymal stem cell; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TDEs, Tumor-derived exosomes; SCLC, Small cell lung cancer; CAF, Cancer-associated fibroblasts; MALAT1, Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1.

Owing to their ability to deliver mRNA and proteins to recipient cells at distant sites, exosomes can promote tumor metastasis and exert immune suppression to evade attack by the immune microenvironment. Gastric cancer cell exosomes establish an immunosuppressive environment for metastatic niche formation and exacerbate lung tumor metastasis [66]. In type 2 diabetes, exosomes released from adipocytes carry thrombospondin 5, which induces metastatic properties associated with the mesenchymal phenotype of breast cancer cells [67]. It is important to note that exosomal PD-L1 exhibits immunosuppressive function in the tumor microenvironment and promotes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade [12]. To note, exosomal PD-L1 from MEL624 cells decreased the proliferation of CD8+ T cells and reduced granzyme B secretion in an in vitro model of melanoma [68]. Moreover, tumor-derived exosomes re-educated neutrophils to exhibit an immunosuppressive microenvironment to promote gastric cancer via high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) activated STAT-3 expression and increase PD-L1 activity [69]. Exosomes derived from patients with non-small cell lung cancer expressed PD-L1 and exhibited tumor escape via decreased IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion [70]. In a syngeneic model of prostate cancer, exosomal PD-L1 was resistant to anti-PD-L1 therapy, and its genetic blockade improved systemic anti-tumor response, strongly indicating the disease-promoting effect of exosomal PD-L1 towards tumor progression [71].

In another instance, exosomes shed from colon cancer cells showcased cetuximab resistance via inhibiting PTEN expression and concurrently, increasing the functional activity of the Akt pathway [72]. Interestingly, exosomes release circular RNA (circSKA3) that potentiates the formation of large colonies and the maintenance of invasiveness in breast cancer [73]. As evident, exosomes from the serum of patients with prostate cancer transfer pyruvate kinase M2 into bone stromal cells and promote its metastasis [74]. Exosome RNF126 derived from tumor cells promoted PTEN ubiquitination and macrophage infiltration, which led to nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression [75]. Melonoma-based exosomes increased PD-1 expression and reprogrammed mesenchymal stem cells to activate oncogenic and survival signals toward tumor metastasis [76]. Tumor exosomes display Tspan8 and CD151 that stimulate angiogenesis and tumor progression [77]. Cancer cell-derived exosomes are reported to stabilize cadherins and promote epithelial to mesenchymal transition that progresses cancer [78]. Taken together, the accumulating evidence concludes the cancer-promoting function of exosomes by subverting immune regulation.

As a bystander in therapy, exosomes of different origins have intrinsic remedial properties that can treat diseases, including cardiovascular, respiratory, kidney and brain disorders. Exosomes have the ability to increase drug half-life and stability by protecting them from degradation by digestive enzymes, and hence, serve as better vehicles for drug delivery in the treatment of cancer and other related diseases. Owing to the numerous undergoing clinical trials of exosome-based therapy, it can be speculated that it might contribute to better responses in patients and can thus be included under standard-of-care therapy for several diseases in the near future (Table 2) [79][80][81][82]. The incorporation of paclitaxel into exosomes exhibited better therapeutic efficacy in pancreatic cancer cells and in NODscid mice (n = 12) [83]. Exosomes have also been used to increase the stability and bioavailability of curcumin to mitigate inflammation and brain tumor growth (n = 5 mice per group) [84]. In fact, curcumin pre-treated lung cancer cells increased exosomal transcriptional factor 21 (TCF21) to subside lung cancer [85]. Doxorubicin-loaded exosomes exhibited higher efficacy with minimal levels of cardiotoxicity [86]. Similarly, exosomes released withaferin at target sites have been tested to treat lung tumor growth [87]. Besides transporting natural cargoes, exosomes are best suited as nanocarriers for the delivery of RNA (mRNA, siRNA, miRNA)-based therapeutics (Table 2). Markedly, specific disease-associated proteins and mRNAs of exosomes can be used as diagnostic markers. Apart from its role in delivering drugs and diagnosis, exosomes can be labeled with CFSE dyes, GFP-expressing plasmids and lipophilic agents (PKH67, Di dyes) to monitor treatment efficacy [88]. In addition, the bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) imaging technique scans the homing of exosomes at the target tissues and organs, which can be used to guide the development of therapeutics [89]. As a therapeutic carrier, diagnostic tool and best imaging agent, exosomes as a comrade outshine their criminal story and prove to be a boon in the medical field.

Table 2. Summary of exosomal cargo in pre-clinical and clinical trials as therapeutics.

| Exosome Source | Exosome Cargo |

Disease | Clinical Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant (Grapes) | Curcumin | Colon cancer | NCT01294072 Phase I |

- |

| Plant (Ginger) | Curcumin | Inflammatory Bowel Disease | NCT04879810 (Completed) |

- |

| Dendritic cell | Dex2 | Non-small cell lung cancer | NCT01159288 (Completed) |

- |

| Plant (Grapes) | Lortab | Oral mucositis | NCT01668849 | - |

| Mesenchymal stromal cells | KRASG12D siRNA | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | NCT03608631 (Phase I) |

- |

| Blood | Anlotinib | Non-small cell lung cancer | NCT05218759 | - |

| Blood | Pembrolizumab | Head and neck cancer | NCT04453046 (Terminated) |

- |

| Dendritic cell/macrophage | Chimeric exosomal tumor vaccines | Bladder cancer | NCT05559177 (Phase I) |

- |

| Circulating lymphocytes and serum | Merck 3475 Pembrolizumab | Triple-negative breast cancer | NCT02977468 (Phase I) |

- |

| Liquid biopsies | 18F-DCFPyL PET/CT | Prostatic neoplasms | NCT03824275 (Phase II/III) |

- |

| Macrophage | CDK-004 | Gastric cancer, colorectal cancer | NCT05375604 (Phase I) |

- |

| Human cell | miR-497 | Lung cancer | - | [79] |

| Dental pulp stem cell | Chitosan hydrogel | Experimental periodontitis | - | [80] |

| MSC-NTF | - | COVID-19-induced ARDS | - | [81] |

| LX-2 cells | Cas9 ribonucleoprotein | Liver diseases | - | [82] |

References

- Agamah, F.E.; Mazandu, G.K.; Hassan, R.; Bope, C.D.; Thomford, N.E.; Ghansah, A.; Chimusa, E.R. Computational/in silico methods in drug target and lead prediction. Brief. Bioinform. 2020, 21, 1663–1675.

- Lin, A.; Giuliano, C.J.; Palladino, A.; John, K.M.; Abramowicz, C.; Yuan, M.L.; Sausville, E.L.; Lukow, D.A.; Liu, L.; Chait, A.R.; et al. Off-target toxicity is a common mechanism of action of cancer drugs undergoing clinical trials. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaw8412.

- Zhao, Z.; Ukidve, A.; Kim, J.; Mitragotri, S. Targeting Strategies for Tissue-Specific Drug Delivery. Cell 2020, 181, 151–167.

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977.

- Boukouris, S.; Mathivanan, S. Exosomes in bodily fluids are a highly stable resource of disease biomarkers. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2015, 9, 358–367.

- Wei, H.; Chen, Q.; Lin, L.; Sha, C.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, L.; Gao, W.; et al. Regulation of exosome production and cargo sorting. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 163–177.

- Lin, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, X. Biological characteristics of exosomes and genetically engineered exosomes for the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents. J. Drug Target. 2019, 28, 129–141.

- Kugeratski, F.G.; Kalluri, R. Exosomes as mediators of immune regulation and immunotherapy in cancer. FEBS J. 2020, 288, 10–35.

- Anel, A.; Gallego-Lleyda, A.; de Miguel, D.; Naval, J.; Martínez-Lostao, L. Role of Exosomes in the Regulation of T-Cell Mediated Immune Responses and in Autoimmune Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 154.

- Ahmadi, M.; Rezaie, J. Tumor cells derived-exosomes as angiogenenic agents: Possible therapeutic implications. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 1–17.

- Maybruck, B.T.; Pfannenstiel, L.W.; Diaz-Montero, M.; Gastman, B.R. Tumor-derived exosomes induce CD8+ T cell suppressors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2017, 5, 65.

- Ye, L.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, J.; Gu, S.; Zhao, X. The Importance of Exosomal PD-L1 in Cancer Progression and Its Potential as a Therapeutic Target. Cells 2021, 10, 3247.

- Skriner, K.; Adolph, K.; Jungblut, P.R.; Burmester, G.R. Association of citrullinated proteins with synovial exosomes. Arthr. Rheum. 2006, 54, 3809–3814.

- Hao, S.; Bai, O.; Yuan, J.; Qureshi, M.; Xiang, J. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes stimulate stronger CD8+ CTL responses and anti-tumor immunity than tumor cell-derived exosomes. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2006, 3, 205–211.

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 7204–7218.

- Wilke, C.M.; Kryczek, I.; Wei, S.; Zhao, E.; Wu, K.; Wang, G.; Zou, W. Th17 cells in cancer: Help or hindrance? Carcinog 2011, 32, 643–649.

- Yang, J.; Sundrud, M.S.; Skepner, J.; Yamagata, T. Targeting Th17 cells in autoimmune diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 493–500.

- Zou, J.Y.; Su, C.H.; Luo, H.H.; Lei, Y.Y.; Zeng, B.; Zhu, H.S.; Chen, Z.G. Curcumin converts Foxp3+ regulatory T cells to T helper 1 cells in patients with lung cancer. J. Cell Biochem. 2017, 119, 1420–1428.

- Gurung, S.; Perocheau, D.; Touramanidou, L.; Baruteau, J. The exosome journey: From biogenesis to uptake and intracellular sig-nalling. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 47.

- Gheinani, A.H.; Vögeli, M.; Baumgartner, U.; Vassella, E.; Draeger, A.; Burkhard, F.C.; Monastyrskaya, K. Improved isolation strategies to increase the yield and purity of human urinary exosomes for biomarker discovery. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3945.

- Sadeghi, S.; Tehrani, F.R.; Tahmasebi, S.; Shafiee, A.; Hashemi, S.M. Exosome engineering in cell therapy and drug delivery. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 145–169.

- Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Zeng, X.; Schwarz, H.; Nanda, H.S.; Peng, X.; Zhou, Y. Exosomes, a new star for targeted delivery. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 2827.

- Andreu, Z.; Yáñez-Mó, M. Tetraspanins in extracellular vesicle formation and function. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 442.

- Wubbolts, R.; Leckie, R.S.; Veenhuizen, P.T.; Schwarzmann, G.; Mȯbius, W.; Hoernschemeyer, J.; Slot, J.W.; Geuze, H.J.; Stoorvogel, W. Proteomic and biochemical analyses of human B cell-derived exosomes: Potential implications for their function and mul-tivesicular body formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 10963–10972.

- Skotland, T.; Hessvik, N.P.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. Exosomal lipid composition and the role of ether lipids and phosphoinositides in exosome biology. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 9–18.

- Zhao, L.; Ma, X.; Yu, J. Exosomes and organ-specific metastasis. Mol. Therapy-Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 22, 133–147.

- Xu, M.; Feng, T.; Liu, B.; Qiu, F.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y. Engineered exosomes: Desirable target-tracking characteristics for cere-brovascular and neurodegenerative disease therapies. Theranostics 2021, 11, 8926.

- Shen, A.-R.; Zhong, X.; Tang, T.-T.; Wang, C.; Jing, J.; Liu, B.-C.; Lv, L.-L. Integrin, Exosome and Kidney Disease. Front. Physiol. 2021, 11, 627800.

- Liang, Y.; Duan, L.; Lu, J.; Xia, J. Engineering exosomes for targeted drug delivery. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3183–3195.

- Wahlund, C.J.E.; Güclüler, G.; Hiltbrunner, S.; Veerman, R.E.; Näslund, T.I.; Gabrielsson, S. Exosomes from antigen-pulsed dendritic cells induce stronger antigen-specific immune responses than microvesicles in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–9.

- Fu, W.; Lei, C.; Liu, S.; Cui, Y.; Wang, C.; Qian, K.; Li, T.; Shen, Y.; Fan, X.; Lin, F.; et al. CAR exosomes derived from effector CAR-T cells have potent antitumour effects and low toxicity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4355.

- Enqvist, M.; Ask, E.H.; Forslund, E.; Carlsten, M.; Abrahamsen, G.; Béziat, V.; Andersson, S.; Schaffer, M.; Spurkland, A.; Bryceson, Y.; et al. Coordinated Expression of DNAM-1 and LFA-1 in Educated NK Cells. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 4518–4527.

- Wang, S.; Shi, Y. Exosomes Derived from Immune Cells: The New Role of Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Tumor Therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 6527–6550.

- Larios, J.; Mercier, V.; Roux, A.; Gruenberg, J. ALIX- and ESCRT-III–dependent sorting of tetraspanins to exosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e201904113.

- Krylova, S.V.; Feng, D. The Machinery of Exosomes: Biogenesis, Release, and Uptake. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1337.

- Colombo, M.; Moita, C.; van Niel, G.; Kowal, J.; Vigneron, J.; Benaroch, P.; Manel, N.; Moita, L.F.; Théry, C.; Raposo, G. Analysis of ESCRT functions in exosome biogenesis, composition and secretion highlights the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 5553–5565.

- Van Niel, G.; Charrin, S.; Simoes, S.; Romao, M.; Rochin, L.; Saftig, P.; Marks, M.S.; Rubinstein, E.; Raposo, G. The tetraspanin CD63 regulates ESCRT-independent and-dependent endosomal sorting during melanogenesis. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 708–721.

- Brosseau, C.; Colas, L.; Magnan, A.; Brouard, S. CD9 Tetraspanin: A New Pathway for the Regulation of Inflammation? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2316.

- Albacete-Albacete, L.; Navarro-Lérida, I.; López, J.A.; Martín-Padura, I.; Astudillo, A.M.; Ferrarini, A.; Van-Der-Heyden, M.; Balsinde, J.; Orend, G.; Vázquez, J.; et al. ECM deposition is driven by caveolin-1–dependent regulation of exosomal biogenesis and cargo sorting. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e202006178.

- Hessvik, N.P.; Llorente, A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 193–208.

- Mashouri, L.; Yousefi, H.; Aref, A.R.; Ahadi, A.M.; Molaei, F.; Alahari, S.K. Exosomes: Composition, biogenesis, and mechanisms in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 75.

- Zhang, Y.; Bi, J.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y.; Du, S.; Li, P. Exosome: A Review of Its Classification, Isolation Techniques, Storage, Diagnostic and Targeted Therapy Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 6917–6934.

- Suharta, S.; Barlian, A.; Hidajah, A.C.; Notobroto, H.B.; Ana, I.D.; Indariani, S.; Wungu, T.D.; Wijaya, C.H. Plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles: A concise review on its extraction methods, content, bioactivities, and potential as functional food ingredient. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2350–2838.

- Lee, H.; Bae, K.; Baek, A.-R.; Kwon, E.-B.; Kim, Y.-H.; Nam, S.-W.; Lee, G.H.; Chang, Y. Glioblastoma-Derived Exosomes as Nanopharmaceutics for Improved Glioma Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1002.

- Cao, Q.; Huang, C.; Chen, X.-M.; Pollock, C.A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Chronic Kidney Disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 816656.

- Kang, M.; Jordan, V.; Blenkiron, C.; Chamley, L.W. Biodistribution of extracellular vesicles following administration into animals: A systematic review. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12085.

- Miyoshi, E.; Bilousova, T.; Melnik, M.; Fakhrutdinov, D.; Poon, W.W.; Vinters, H.V.; Miller, C.A.; Corrada, M.; Kawas, C.; Bohannan, R.; et al. Exosomal tau with seeding activity is released from Alzheimer’s disease synapses, and seeding potential is associ-ated with amyloid beta. Lab. Investig. 2021, 101, 1605–1617.

- Guo, M.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Han, S.; Dong, Q.; Cui, M.; Tieu, K. Microglial exosomes facilitate α-synuclein transmission in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2020, 143, 1476–1497.

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.K.; Lee, E.Y.; Lee, E.B.; Song, Y.W. Circulating exosomes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus induce a proinflammatory immune response. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2016, 18, 264.

- Ding, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, S. Exosomes derived from synovial fibroblasts under hypoxia aggravate rheumatoid arthritis by regulating Treg/Th17 balance. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 1177–1186.

- Ding, H.; Li, L.X.; Harris, P.C.; Yang, J.; Li, X. Extracellular vesicles and exosomes generated from cystic renal epithelial cells promote cyst growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–18.

- Wang, J.; Yue, B.-L.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Lan, X.-Y.; Liu, W.-J.; Chen, H. Exosomal RNAs: Novel Potential Biomarkers for Diseases—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2461.

- Gao, C.; Wang, B.; Chen, Q.; Wang, M.; Fei, X.; Zhao, N. Serum exosomes from diabetic kidney disease patients promote pyroptosis and oxidative stress through the miR-4449/HIC1 pathway. Nutr. Diabet. 2021, 11, 33.

- Li, Q.; Li, B.; Wei, S.; He, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Xia, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, W.; et al. Exosomal miR-21-5p derived from gastric cancer promotes peritoneal metastasis via mesothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 854.

- Li, Y.; Yin, Z.; Fan, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, W. The roles of exosomal miRNAs and lncRNAs in lung diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 47.

- Garcia, G.; Pinto, S.; Ferreira, S.; Lopes, D.; Serrador, M.J.; Fernandes, A.; Vaz, A.R.; de Mendonça, A.; Edenhofer, F.; Malm, T.; et al. Emerging Role of miR-21-5p in Neuron–Glia Dysregulation and Exosome Transfer Using Multiple Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 3377.

- Wang, W.; Hong, G.; Wang, S.; Gao, W.; Wang, P. Tumor-derived exosomal miRNA-141 promote angiogenesis and malignant pro-gression of lung cancer by targeting growth arrest-specific homeobox gene (GAX). Bioengineered 2021, 12, 821–831.

- Ren, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Feng, Q.; Feng, H.; Tong, Y.; Rong, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Exosomal miRNA-107 induces myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion in gastric cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 4023–4040.

- Mao, S.; Zheng, S.; Lu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Xu, H.; Huang, J.; Lei, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. Exosomal miR-375-3p breaks vascular barrier and promotes small cell lung cancer metastasis by targeting claudin-1. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 3155–3172.

- Yu, Y.; Bai, F.; Qin, N.; Liu, W.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J. Non-proximal renal tubule-derived urinary exosomal miR-200b as a biomarker of renal fibrosis. Nephron 2018, 139, 269–282.

- Lang, H.L.; Hu, G.W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tu, W.; Lu, Y.M.; Wu, L.; Xu, G.H. Glioma cells promote angiogenesis through the release of exosomes containing long non-coding RNA POU3F3. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 959–972.

- Sun, Y.; Hao, G.; Zhuang, M.; Lv, H.; Liu, C.; Su, K. MEG3 LncRNA from Exosomes Released from Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Enhances Cisplatin Chemoresistance in SCLC via a MiR-15a-5p/CCNE1 Axis. Yonsei Med. J. 2022, 63, 229–240.

- Zhang, P.; Zhou, H.; Lu, K.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, T. Exosome-mediated delivery of MALAT1 induces cell proliferation in breast cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 291–299.

- Li, Z.; Yanfang, W.U.; Li, J.; Jiang, P.; Peng, T.; Chen, K.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhen, P.; Zhu, J.; et al. Tumor-released exosomal circular RNA PDE8A promotes invasive growth via the miR-338/MACC1/MET pathway in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018, 432, 237–250.

- Dai, X.; Chen, C.; Yang, Q.; Xue, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, B.; Luo, F.; Liu, X.; Xiao, T.; Xu, H.; et al. Exosomal circRNA_100284 from arsenite-transformed cells, via microRNA-217 regulation of EZH2, is involved in the malignant transformation of human hepatic cells by accelerating the cell cycle and promoting cell proliferation. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 454.

- Liu, J.; Wu, S.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, P.; Fu, Y.; Wu, C.; Lu, B.; Ju, J.; Jiang, J. Immune suppressed tumor microenvironment by exosomes derived from gastric cancer cells via modulating immune functions. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14749.

- Jafari, N.; Kolla, M.; Meshulam, T.; Shafran, J.S.; Qiu, Y.; Casey, A.N.; Pompa, I.R.; Ennis, C.S.; Mazzeo, C.S.; Rabhi, N.; et al. Adipo-cyte-derived exosomes may promote breast cancer progression in type 2 diabetes. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, eabj2807.

- Chen, G.; Huang, A.C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, G.; Wu, M.; Xu, W.; Yu, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; et al. Exosomal PD-L1 contributes to immunosuppression and is associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature 2018, 560, 382–386.

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Mao, Z.; Jiang, H.; Liu, W.; Shi, H.; Ji, R.; Xu, W.; Qian, H.; Zhang, X. Extracellular Vesicles from Gastric Cancer Cells Induce PD-L1 Expression on Neutrophils to Suppress T-Cell Immunity. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 629.

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, H.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.-E.; Sung, K.J.; Sung, Y.H.; Pack, C.-G.; Jung, M.-K.; Han, B.; et al. Exosomal PD-L1 promotes tumor growth through immune escape in non-small cell lung cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–13.

- Poggio, M.; Hu, T.; Pai, C.-C.; Chu, B.; Belair, C.D.; Chang, A.; Montabana, E.; Lang, U.E.; Fu, Q.; Fong, L.; et al. Suppression of exosomal PD-L1 induces systemic anti-tumor immunity and memory. Cell 2019, 177, 414–427.e413.

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, J.; Che, X.; Fan, Y.; Hou, K.; Guo, T.; Deng, G.; Song, N.; Li, C.; et al. Exosomes promote cetuximab resistance via the PTEN/Akt pathway in colon cancer cells. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2018, 51, e6472.

- Du, W.W.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Fang, L.; Wu, N.; Li, F.; Dhaliwal, P.; Yang, W.; Yee, A.J.; Yang, B.B. Promotion of tumor progression by exosome transmission of circular RNA circSKA3. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 276–292.

- Dai, J.; Escara-Wilke, J.; Keller, J.M.; Jung, Y.; Taichman, R.S.; Pienta, K.J.; Keller, E.T. Primary prostate cancer educates bone stroma through exosomal pyruvate kinase M2 to promote bone metastasis. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 2883–2899.

- Yu, C.; Xue, B.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q. Tumor cell-derived exosome RNF126 affects the immune microenvironment and promotes naso-pharyngeal carcinoma progression by regulating PTEN ubiquitination. Apoptosis 2022, 27, 590–605.

- Gyukity-Sebestyén, E.; Harmati, M.; Dobra, G.; Németh, I.B.; Mihály, J.; Zvara, Á.; Hunyadi-Gulyás, É.; Katona, R.; Nagy, I.; Horváth, P.; et al. Melanoma-derived exosomes induce PD-1 overexpression and tumor progression via mesenchymal stem cell onco-genic reprogramming. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2459.

- Zhao, K.; Wang, Z.; Hackert, T.; Pitzer, C.; Zöller, M. Tspan8 and Tspan8/CD151 knockout mice unravel the contribution of tumor and host exosomes to tumor progression. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 312.

- Wang, B.; Tan, Z.; Guan, F. Tumor-Derived Exosomes Mediate the Instability of Cadherins and Promote Tumor Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3652.

- Jeong, K.; Yu, Y.J.; You, J.Y.; Rhee, W.J.; Kim, J.A. Exosome-mediated microRNA-497 delivery for anti-cancer therapy in a microfluidic 3D lung cancer model. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 548–557.

- Wu, X.; Jin, S.; Ding, C.; Wang, Y.; He, D.; Liu, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosome Therapy of Microbial Diseases: From Bench to Bed. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 4007.

- Kaspi, H.; Semo, J.; Abramov, N.; Dekel, C.; Lindborg, S.; Kern, R.; Lebovits, C.; Aricha, R. MSC-NTF (NurOwn®) exosomes: A novel therapeutic modality in the mouse LPS-induced ARDS model. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 72.

- Wan, T.; Zhong, J.; Pan, Q.; Zhou, T.; Ping, Y.; Liu, X. Exosome-mediated delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes for tis-sue-specific gene therapy of liver diseases. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabp9435.

- Melzer, C.; Rehn, V.; Yang, Y.; Bähre, H.; von der Ohe, J.; Hass, R. Taxol-Loaded MSC-Derived Exosomes Provide a Therapeutic Vehicle to Target Metastatic Breast Cancer and Other Carcinoma Cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 798.

- Zhuang, X.; Xiang, X.; Grizzle, W.; Sun, D.; Zhang, S.; Axtell, R.C.; Ju, S.; Mu, J.; Zhang, L.; Steinman, L.; et al. Treatment of Brain Inflammatory Diseases by Delivering Exosome Encapsulated Anti-inflammatory Drugs from the Nasal Region to the Brain. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 1769–1779.

- Wu, H.; Zhou, J.; Zeng, C.; Wu, D.; Mu, Z.; Chen, B.; Xie, Y.; Ye, Y.; Liu, J. Curcumin increases exosomal TCF21 thus suppressing exo-some-induced lung cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 87081.

- Toffoli, G.; Hadla, M.; Corona, G.; Caligiuri, I.; Palazzolo, S.; Semeraro, S.; Gamini, A.; Canzonieri, V.; Rizzolio, F. Exosomal doxorubicin reduces the cardiac toxicity of doxorubicin. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 2963–2971.

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, M. Exosome-Based Cancer Therapy: Implication for Targeting Cancer Stem Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 7, 533.

- Shen, L.-M.; Quan, L.; Liu, J. Tracking Exosomes in Vitro and in Vivo To Elucidate Their Physiological Functions: Implications for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Nanocarriers. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 2438–2448.

- Hikita, T.; Miyata, M.; Watanabe, R.; Oneyama, C. In vivo imaging of long-term accumulation of cancer-derived exosomes using a BRET-based reporter. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16616.

More

Information

Subjects:

Integrative & Complementary Medicine

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

769

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 May 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No