Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Emanuela Gualdi-Russo | -- | 1484 | 2023-05-05 18:34:06 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | Meta information modification | 1484 | 2023-05-06 08:06:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Zaccagni, L.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Sports Involvement on Body Image Perception and Ideals. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43891 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Zaccagni L, Gualdi-Russo E. Sports Involvement on Body Image Perception and Ideals. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43891. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Zaccagni, Luciana, Emanuela Gualdi-Russo. "Sports Involvement on Body Image Perception and Ideals" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43891 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Zaccagni, L., & Gualdi-Russo, E. (2023, May 05). Sports Involvement on Body Image Perception and Ideals. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43891

Zaccagni, Luciana and Emanuela Gualdi-Russo. "Sports Involvement on Body Image Perception and Ideals." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 May, 2023.

Copy Citation

Concerns about body image may affect athletes, mainly because of specific sports models to achieve successful performance.

body dissatisfaction

body image

athletes

1. Introduction

Any form of physical activity can be beneficial to the physical and mental health of youth and adults when undertaken regularly and with sufficient duration and intensity [1][2]. These recommendations are highly relevant since there is simultaneously a worldwide prevalence of physical inactivity and obesity. Indeed, the current sedentary lifestyle is one of the main causes of overweight/obesity [3][4], and this results in a high prevalence of dissatisfaction with the perceived body image (BI) because of the ideal of body thinness prevalent in Western societies [5].

Sports make an important, though underused, contribution to the physical activity of persons of every age [1]. Athletes are engaged in structured and planned physical activity with prominent influences on their physical and mental health. Generally, a positive BI is associated with increased participation in physical activity and sports [6]. BI is considered a multidimensional construct focused on the appearance and function of the body [6]. Body dissatisfaction with an individual’s own physical appearance and body size, as well as discrepancies between actual and ideal dimensions, are cognitive, affective, and perceptual indicators of a negative BI [7]. In essence, a negative or positive BI is shown through the perceptual dimension (how I see myself), and cognitive and affective dimensions (how I think and feel about my physical appearance) [7].

In a sports context, a more favorable BI would depend on actual physical changes resulting from the sport practiced (e.g., body shape), perceived changes in the physique, and building self-efficacy and confidence. However, this relationship is by no means simple: while physical activity practice contributes to raising self-confidence through a number of discernible physical changes (e.g., an increase in fat-free-mass) resulting in improved BI satisfaction, BI may, in turn, induce motivation or dissuasion for physical activity and sports participation [6]. Thus, for example, exercise addiction arises from a misperception of BI [8] and can also result in decreased performance owing to overload and physical burnout [9].

An important aspect to consider is whether dissatisfaction is influenced by the type of exercise practiced. Some differences in body dissatisfaction recorded among practitioners of different sports [10] might depend on the importance of body weight and body thinness within that sport [11]. A particular relevance of physical appearance can be found in aesthetic sports, such as rhythmic gymnastics. In this case, the assessment of the athlete considers his/her morpho-kinetic abilities based on well-coded aesthetic requirements. Therefore, in addition to performance, the athlete’s physical appearance strongly contributes to the judgment, so much so that a prevalence of dissatisfaction among athletes involved in aesthetic sports has been reported in several studies [12][13]. With particular reference to the female gender, a higher risk of body concerns was observed in gymnastics than in swimming and long-distance running [14]. However, in these cases, it is important to distinguish the “sport” body image dissatisfaction (sport-BID = perceived discrepancy between current and ideal body size for sport) from the general body image dissatisfaction (BID) [15][16]. Indeed, the literature [15] shows that athletes, especially in aesthetic sports, would not be driven toward dieting and pathological weight control because of general BID, but because of the specific needs of the sport they play. Greenleaf [17] distinguished the BI of the athlete within an athletic context from a social BI that relates to the context of everyday life. Satisfaction/dissatisfaction with one’s body image will therefore depend not only on one’s physical appearance, but also on the social or sports environment of reference. Although athletes tend to be more satisfied than non-athletes in the social environment [18], in the sports environment, athletes often are under pressure from coaches and athletic trainers to achieve and retain a body that is favorable to their respective sport [19]. Regarding aesthetic sports, for example, it has been found that the ideal sports figure of the female gymnast does not coincide with the ideal figure in everyday life, being leaner [16].

According to previous literature reviews, athletes have a more positive BI than non-athletes both considering studies published between 1975 and 2000 [18] and between 2000 and 2012 [14]. Although both reviews made this comparison taking into account age and competitive level, no gender comparisons were made in either the first review (which reports a small percentage of males) or the second review (focused exclusively on females). The majority of studies in this field concern eating disorders, showing a higher incidence of disordered eating in athletes, particularly in aesthetic and weight-class-dependent sports [20]. De Bruin et al. [15] analyzed the role of BI in athletes’ disordered eating, showing that the athletic BI contributes greatly to this symptomatology. To date, research has focused primarily on the impact of negative BI on the athlete or pathological aspects without thoroughly considering the framework [21].

2. BID by Gender

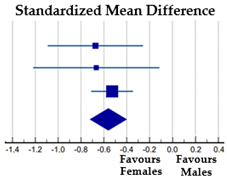

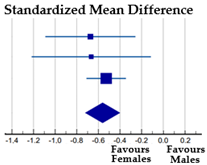

Four studies (27%) included in the review analyzed athletes of both genders, but Krentz and Warschburger [22], Cardoso et al. [23], and Da Silva et al. [24] did not consider BID, so only the study (7%) of Francisco et al. [25] reported the necessary data to calculate the effect size. They reported the number, mean, and SD of male and female elite aesthetic athletes, non-elite aesthetic athletes, and non-aesthetic athletes (Table 1).

Table 1. BID by gender: results of the meta-analysis.

| Females | Males | % |  |

||||||

| Subgroup | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | Weight | SMD [95% CI] | |

| Elite aesthetic athletes [25] | 101 | −0.88 | 1.21 | 30 | −0.11 | 0.83 | 14.86 | −0.67 [−1.09, −0.26] | |

| Non-elite aesthetic athletes [25] | 99 | −0.51 | 1.19 | 15 | 0.27 | 0.96 | 8.51 | −0.67 [−1.22, −0.14] | |

| Non-aesthetic athletes [25] | 253 | −0.81 | 1.31 | 227 | −0.17 | 1.09 | 76.64 | −0.53 [−0.71, −0.35] | |

| Total (random effects) | 453 | 272 | 100.00 | −0.56 [−0.72, −0.40] | |||||

The meta-analysis on a total of 725 athletes revealed a medium and significant effect of gender on BID, with girls more dissatisfied than boys (SMD = −0.56, p < 0.001). The Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics revealed no heterogeneity among the studies (χ2 = 0.558, DF = 2, p = 0.757; I2 = 0.0%).

3. BID by Type of Sports: Aesthetic Sports vs. Non-Aesthetic Sports

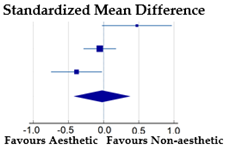

Only three studies (20%) on female athletes (two on adolescents [25][26] and one on young adults [27]) reported the necessary data to perform a meta-analysis on the effect of sport type on BID based on a total of 582 female subjects: 201 girls engaged in aesthetic sports (at elite level) and 381 girls engaged in non-aesthetic sports (Table 2).

Table 2. BID by type of sports in female athletes.

| Aesthetic Sports | Non-Aesthetic Sports | % |  |

||||||

| Study | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | Weight | SMD [95% CI] | |

| Borrione et al. [26] | 20 | −0.5 | 0.8 | 80 | −1.0 | 1.1 | 26.91 | 0.47 [−0.02, 0.97] | |

| Francisco et al. [25] | 101 | −0.88 | 1.21 | 253 | −0.81 | 1.31 | 39.76 | −0.05 [−0.29, 0.18] | |

| Kong and Harris [27] | 80 | −1.34 | 1.09 | 48 | −0.94 | 0.93 | 33.33 | −0.39 [−0.75, −0.23] | |

| Total (random effects) | 201 | 381 | 100.00 | −0.02 [−0.42, 0.37] | |||||

Meta-analysis revealed a non-significant effect of the type of sports on BID in female athletes (SMD = −0.02; p = 0.899). The Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics revealed a significant heterogeneity among the studies considered (χ2 = 7.68, DF = 2, p = 0.02; I2 = 73.96%).

4. BID by the Level of Sport: Elite Level vs. Non-Elite Level in Aesthetic Sports

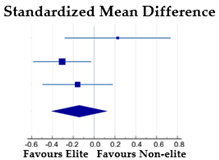

The same studies examined in the above analysis were used to perform a meta-analysis on the effect of the level of aesthetic sports on BID (Table 3) based on 420 female subjects.

Table 3. BID by the level of sports in female athletes.

| Elite Level | Non-Elite Level | % |  |

||||||

| Study | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | Weight | SMD [95% CI] | |

| Borrione et al. [26] | 20 | −0.5 | 0.8 | 61 | −0.7 | 0.9 | 20.93 | 0.23 [−0.28, 0.74] | |

| Francisco et al. [25] | 101 | −0.88 | 1.21 | 99 | −0.51 | 1.19 | 43.39 | −0.31 [−0.59, −0.03] | |

| Kong and Harris. [27] | 80 | −1.34 | 1.09 | 59 | −1.15 | 1.32 | 35.68 | −0.16 [−0.50, 0.18] | |

| Total (random effects) | 201 | 219 | 100.00 | −0.14 [−0.41, 0.12] | |||||

The meta-analysis revealed a small and non-significant effect of the elite level in aesthetic sports on BID compared to the non-elite level (SMD = −0.14; p = 0.293). The Cochran’s Q test (χ2 = 3.334, DF = 2, p = 0.189) and I2 statistics (40.01%) revealed a moderate and non-significant heterogeneity among the studies considered.

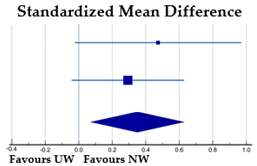

5. BID by Weight Status: Underweight Athletes vs. Normal-Weight Athletes

Taking into account the mean BMI values, only the study of Borrione et al. [26] considered underweight and normal-weight athletes: the international- and national-level rhythmic gymnasts’ mean BMI value fell in the underweight category, while the controls’ (athletes practicing basketball, volleyball, Taekwondo) mean BMI values fell into the normal-weight category. The meta-analysis revealed a small (SMD = 0.35), but significant (p = 0.014) effect of the weight status on BID, with underweight athletes less dissatisfied than those of normal weight, despite the fact that the former practiced an aesthetic sport and the latter sports non-focused on leanness. The Cochran’s Q test (χ2 = 0.355, DF = 1, p = 0.551) and I2 statistics (0%) revealed no heterogeneity among the samples considered (Table 4).

Table 4. BID by weight status in female athletes.

| Underweight | Normal-Weight |  |

|||||||

| Subgroup | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | Weight | SMD [95% CI] | |

| UW (international RG) vs. NW (controls) [26] | 20 | −0.5 | 0.8 | 80 | −1.0 | 1.1 | 31.55 | 0.47 [−0.02, 0.97] | |

| UW (national RG) vs NW (controls) [26] | 61 | −0.8 | 0.9 | 80 | −1.0 | 1.1 | 68.45 | 0.29 [−0.04, 0.63] | |

| Total (random effects) | 81 | 160 | 100.00 | 0.35 [0.07, 0.63] | |||||

6. Sport-BID by Gender

Four studies (27%) provided information about the influence of gender on sport-BID; a meta-analysis was performed based on a total of 501 participants (413 females and 88 males), all engaged in aesthetic sports at an elite level. Voelker et al. [28] reported data for female figure skaters and Voelker et al. [29] reported data for male figure skaters. The meta-analysis revealed a moderate and significant effect of gender on sport-BID: female athletes are more dissatisfied about their actual body size concerning their ideal sport-practiced body size compared to the males (SMD = −0.74; p < 0.001). The Cochran’s Q test (χ2 = 3.935, DF = 3, p = 0.269) and I2 statistics (23.76%) revealed no heterogeneity among the studies considered (Table 5).

Table 5. Effect of gender on Sport-BID in elite aesthetic athletes.

| Females | Males |  |

|||||||

| Subgroup | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | Weight% | SMD [95% CI] | |

| Elite dancers [30] | 53 | −1.45 | 1.32 | 13 | 0.08 | 0.95 | 17.05 | −1.20 [−1.85, −0.56] | |

| Elite gymnasts [30] | 50 | −1.20 | 1.04 | 19 | −0.58 | 1.02 | 22.66 | −0.59 [−1.13, −0.05] | |

| Elite figure skaters [28][29] | 272 | −1.00 | 1.48 | 29 | −0.26 | 0.77 | 36.18 | −0.52 [−0.90, −0.13] | |

| Elite aesthetic sports [22] | 38 | −0.80 | 1.00 | 27 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 24.10 | −0.89 [−1.41, −0.37] | |

| Total (random effects) | 413 | 88 | 100.00 | −0.74 [−1.03, −0.46] | |||||

References

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for A Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599979 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Heterogeneous contributions of change in population distribution of body mass index to change in obesity and underweight. eLife 2021, 10, e60060.

- Gualdi-Russo, E.; Rinaldo, N.; Masotti, S.; Bramanti, B.; Zaccagni, L. Sex Differences in Body Image Perception and Ideals: Analysis of Possible Determinants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2745.

- Sabiston, C.M.; Pila, E.; Vani, M.; Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. Body image, physical activity, and sport: A scoping review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 48–57.

- Marschin, V.; Herbert, C. Yoga, Dance, Team Sports, or Individual Sports: Does the Type of Exercise Matter? An Online Study Investigating the Relationships Between Different Types of Exercise, Body Image, and Well-Being in Regular Exercise Practitioners. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 621272.

- Badau, D.; Badau, A. Identifying the Incidence of Exercise Dependence Attitudes, Levels of Body Perception, and Preferences for Use of Fitness Technology Monitoring. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2614.

- Angeli, A.; Minetto, M.; Dovio, A.; Paccotti, P. The overtraining syndrome in athletes: A stress-related disorder. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2004, 27, 603–612.

- Morano, M.; Colella, D.; Capranica, L. Body image, perceived and actual physical abilities in normal-weight and overweight boys involved in individual and team sports. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 355–362.

- Dyremyhr, Å.E.; Diaz, E.; Meland, E. How adolescent subjective health and satisfaction with weight and body shape are related to participation in sports. J. Environ. Public Health 2014, 2014, 851932.

- Francisco, R.; Alarcão, M.; Narciso, I. Aesthetic sports as high-risk contexts for eating disorders: Young elite dancers and gymnasts perspectives. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 265–274.

- Lepage, M.L.; Crowther, J.H. The effects of exercise on body satisfaction and affect. Body Image 2010, 7, 124–130.

- Varnes, J.R.; Stellefson, M.L.; Janelle, C.M.; Dorman, S.M.; Dodd, V.; Miller, M.D. A systematic review of studies comparing body image concerns among female college athletes and non-athletes, 1997–2012. Body Image 2013, 10, 421–432.

- De Bruin, A.P.; Oudejans, R.R.D.; Bakker, F.C.; Woertman, L. Contextual body image and athletes’ disordered eating: The contribution of athletic body image to disordered eating in high performance women athletes. Eur. Eat. Disord Rev. 2011, 19, 201–215.

- Zaccagni, L.; Barbieri, D.; Gualdi-Russo, E. Body composition and physical activity in Italian university students. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 120.

- Greenleaf, C. Athletic body image: Exploratory interviews with former female competitive athletes. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2002, 11, 63–88.

- Hausenblas, H.; Symons Downs, D. Comparison of body image between athletes and nonathletes: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2001, 13, 323–339.

- Brown, D.M.; Muir, C.; Gammage, K.L. Muscle Up: Male Athletes’ and Non-Athletes’ Psychobiological Responses to, and Recovery From, Body Image Social-Evaluative Threats. Am. J. Men’s Health 2023, 17, 15579883231155089.

- Hausenblas, H.A.; Carron, A.V. Eating disorder indices and athletes: An integration. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1999, 21, 230–258.

- Soulliard, Z.A.; Kauffman, A.A.; Fitterman-Harris, H.F.; Perry, J.E.; Ross, M.J. Examining positive body image, sport confidence, flow state, and subjective performance among student athletes and non-athletes. Body Image 2019, 28, 93–100.

- Krentz, E.M.; Warschburger, P. A longitudinal investigation of sports-related risk factors for disordered eating in aesthetic sports. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, 303–310.

- Cardoso, A.A.; Reis, N.M.; Moratelli, J.; Borgatto, A.; Resende, R.; de Souza Guidarini, F.C.; de Azevedo Guimarães, A.C. Body Image Dissatisfaction, Eating Disorders, and Associated Factors in Brazilian Professional Ballroom Dancers. J. Danc. Med. Sci. 2021, 25, 18–23.

- Da Silva, C.L.; De Oliveira, E.P.; De Sousa, M.V.; Pimentel, G.D. Body dissatisfaction and the wish for different silhouette is associated with higher adiposity and fat intake in female ballet dancers than male. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2016, 56, 141–148.

- Francisco, R.; Narciso, I.; Alarcão, M. Individual and relational risk factors for the development of eating disorders in adolescent aesthetic athletes and general adolescents. Eat. Weight Disord. 2013, 18, 403–411.

- Borrione, P.; Battaglia, C.; Fiorilli, G.; Moffa, S.; Despina, T.; Piazza, M.; Calcagno, G.; Di Cagno, A. Body image perception and satisfaction in elite rhythmic gymnasts: A controlled study. Med. Dello Sport 2013, 66, 61–70.

- Kong, P.; Harris, L.M. The sporting body: Body image and eating disorder symptomatology among female athletes from leanness focused and nonleanness focused sports. J. Psychol. 2015, 149, 141–160.

- Voelker, D.K.; Gould, D.; Reel, J.J. Prevalence and correlates of disordered eating in female figure skaters. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014, 15, 696–704.

- Voelker, D.K.; Trent, A.P.; Reel, J.J.; Gould, D. Frequency and psychosocial correlates of eating disorder symptomatology in male figure skaters. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2017, 30, 119–126.

- Francisco, R.; Narciso, I.; Alarcao, M. Specific predictors of disordered eating among elite and non-elite gymnasts and ballet dancers. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2012, 43, 479–502.

More

Information

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

904

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 May 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No