| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Javier Curi de Bardet | -- | 2041 | 2023-05-04 18:07:14 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2041 | 2023-05-05 10:42:09 | | |

Video Upload Options

Somatic human cells can divide a finite number of times, a phenomenon known as the Hayflick limit. It is based on the progressive erosion of the telomeric ends each time the cell completes a replicative cycle. Given this problem, researchers need cell lines that do not enter the senescence phase after a certain number of divisions. In this way, more lasting studies can be carried out over time and avoid the tedious work involved in performing cell passes to fresh media. However, some cells have a high replicative potential, such as embryonic stem cells and cancer cells. To accomplish this, these cells express the enzyme telomerase or activate the mechanisms of alternative telomere elongation, which favors the maintenance of the length of their stable telomeres. Researchers have been able to develop cell immortalization technology by studying the cellular and molecular bases of both mechanisms and the genes involved in the control of the cell cycle. Through it, cells with infinite replicative capacity are obtained. To obtain them, viral oncogenes/oncoproteins, myc genes, ectopic expression of telomerase, and the manipulation of genes that regulate the cell cycle, such as p53 and Rb, have been used.

1. Introduction

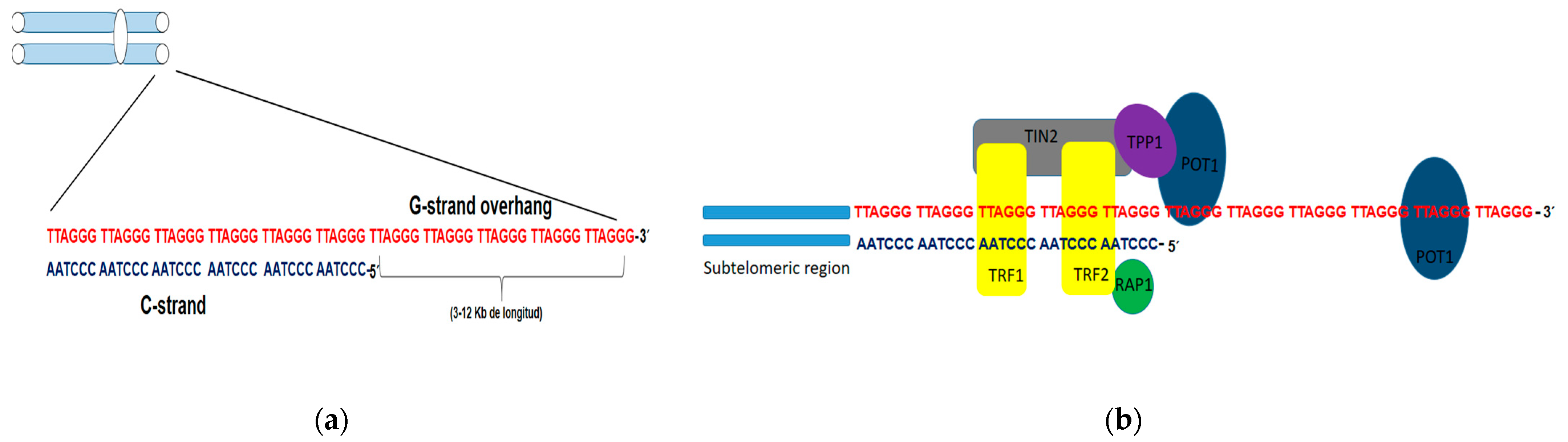

1.1. Telomeres

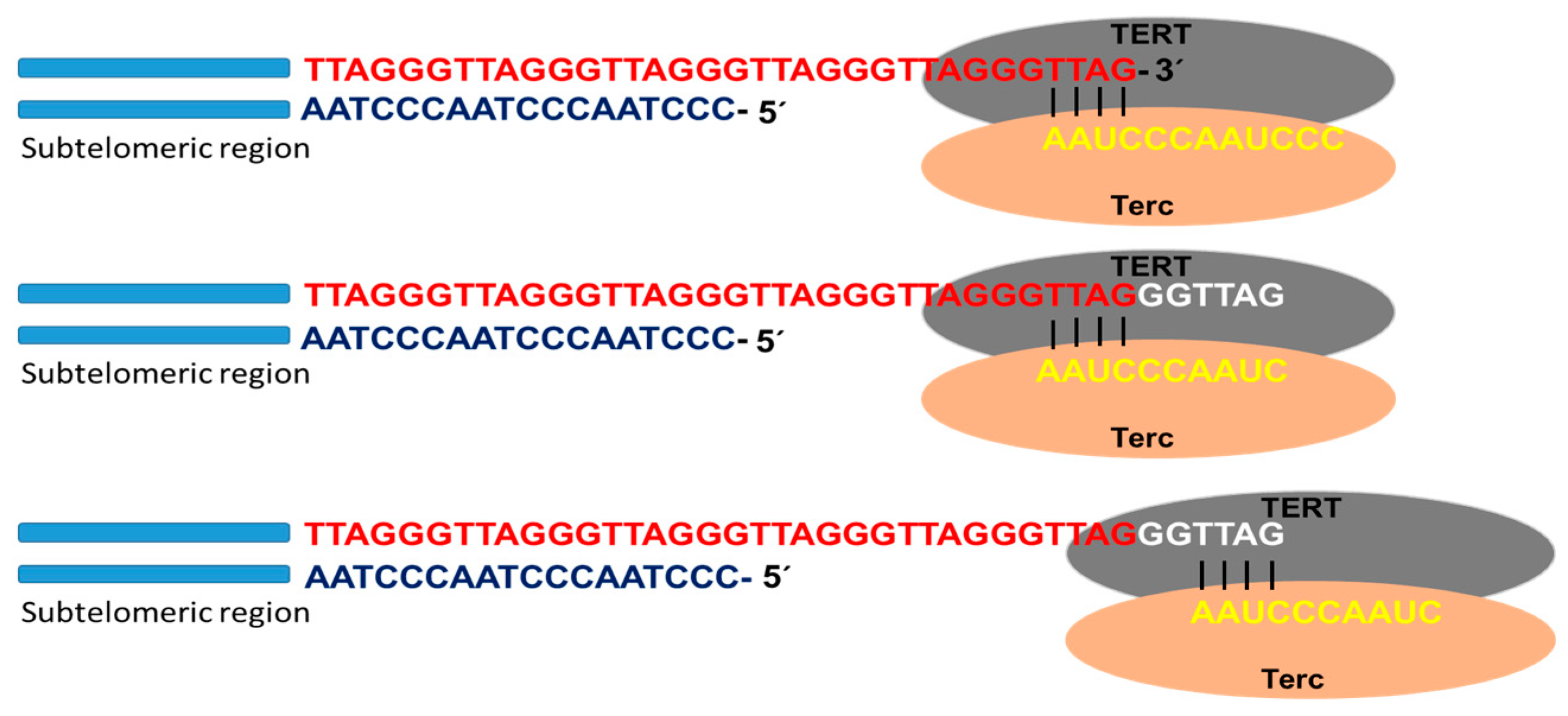

1.2. Mechanism Involved in Lengthening of Telomeres

Telomerase

2. Alternative Telomere Lengthening (ALT)

3. Coexistence of Telomerase and the ALT Pathway

References

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P.S. The Serial Cultivation of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1961, 1, 585–621.

- Hayflick, L. How and why we age. Exp. Gerontol. 1998, 33, 377.

- Hayflick, L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1965, 37, 614–636.

- Blackburn, E.H. Telomeres—No end in sight. Cell 1994, 77, 621–623.

- Shay, J.W.; Bacchetti, S. A survey of telomerase activity in human cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 1997, 33, 787–791.

- Heaphy, C.M.; Subhawong, A.P.; Hong, S.M.; Goggins, M.G.; Montgomery, E.A.; Gabrielson, E.; Heaphy, C.M.; Subhawong, A.P.; Hong, S.M.; Goggins, M.G.; et al. Prevalence of the alternative lengthening of telomeres telomere maintenance mechanism in human cancer subtypes. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 179, 1608–1615.

- Arnoult, N.; Karlseder, J. Complex interactions between the DNA-damage response and mammalian telomeres. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 859–866.

- Denchi, E.L.; de Lange, T. Protection of telomeres through independent control of ATM and ATR by TRF2 and POT1. Nature 2007, 448, 1068–1071.

- Harley, C.B.; Futcher, A.B.; Greider, C.W. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 1990, 345, 458–460.

- Doksani, Y.; Wu, J.Y.; de Lange, T.; Zhuang, X. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging of telomeres reveals TRF2-dependent T-loop formation. Cell 2013, 155, 345–356.

- Rai, R.; Zheng, H.; He, H.; Luo, Y.; Multani, A.; Carpenter, P.B.; Chang, S. The function of classical and alternative non-homologous end-joining pathways in the fusion of dysfunctional telomeres. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 2598–2610.

- Okamoto, K.; Bartocci, C.; Ouzounov, I.; Diedrich, J.K.; Yates, J.R.; Denchi, E.L. A two-step mechanism for TRF2- mediated chromosome-end protection. Nature 2013, 494, 502–505.

- Maciejowski, J.; de Lange, T. Telomeres in Cancer: Tumour suppression and genome instability. Nat. Rev. 2017, 18, 175–186.

- Shay, J.W. Role of telomeres and telomerase in aging and cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 584–593.

- Cohen, S.B.; Graham, M.E.; Lovrecz, G.O.; Bache, N.; Robinson, P.J.; Reddel, R.R. Protein composition of catalytically active human telomerase from immortal cells. Science 2007, 315, 1850–1853.

- Blackburn, E.H. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell 2001, 106, 661–673.

- Greider, C.W.; Blackburn, E.H. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell 1985, 43, 405–413.

- De Vitis, M.; Berardinelli, F.; Sgura, A. Telomere lenght maintenence in Cancer: AT the Crossroad between Telomerase and Alternative Lenthening of Telomeres (ALT). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 606.

- Harrington, L. Does the reservoir for self-renewal stem from the ends? Oncogene 2004, 23, 7283–7289.

- Gunes, C.; Lenhard, R.K. The role of the telomeres in stem cells and cancer. Cell 2013, 152, 390–393.

- Sperka, T.; Wang, J.; Rudolph, K.L. DNA damage checkpoints in stem cells, ageing and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 579–590.

- Okamoto, K.; Seimiya, H. Revisiting telomeres shortening in Cancer. Cells 2019, 8, 107.

- Begus-Nahrmann, Y.; Hartmman, D.; Kraus, J.; Eshragi, P.; Scheffold, A.; Grieb, M.; Rasche, V.; Schirmacher, P.; Lee, H.W.; Kestler, H.A.; et al. Transient telomere dysfunction induces chromosomal instability and promotes carcinogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2283–2288.

- Barthel, F.P.; Wei, W.; Tang, M.; Martinez-Ledesma, E.; Hu, X.; Amin, S.B.; Akdemir, K.C.; Seth, S.; Song, X.; Wang, Q.; et al. Systematic analysis of telomere length and somatic alterations in 31 cancer types. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 349–357.

- Bell, R.J.; Rube, H.T.; Kreig, A.; Mancini, A.; Fouse, S.D.; Nagarajan, R.P.; Choi, S.; Hong, C.; He, D.; Pekmezci, M.; et al. Cancer. The transcription factor GABP selectively binds and activates the mutant TERT promoter in cancer. Science 2015, 348, 1036–1039.

- Stern, J.L.; Theodorescu, D.; Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Cech, T.R. Mutation of the TERT promoter, switch to active chromatin and monoallelic TERT expression in multiple cancers. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 2219–2224.

- Weinhold, N.; Jacobsen, A.; Schultz, N.; Sander, C.; Lee, W. Genome-wide analysis of noncoding regulatory mutations in cancer. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 1160–1165.

- Hayward, N.K.; Wilmott, J.S.; Waddell, N.; Johansson, P.A.; Field, M.A.; Nones, K.; Patch, A.M.; Kakavand, H.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Burke, H.; et al. Whole-genome landscapes of major melanoma subtypes. Nature 2017, 545, 175–180.

- Labussière, M.; Boisselier, B.; Mokhtari, K.; DiStefano, A.L.; Rahimian, A.; Rossetto, M.; Ciccarino, P.; Saulnier, O.; Paterra, R.; Marie, Y.; et al. Combined analysis of TERT, EGFR, and IDH status defines distinct prognostic glioblastoma classes. Neurology 2014, 83, 1200–1206.

- Spiegl-Kreinecker, S.; Lötsch, D.; Neumayer, K.; Kastler, L.; Gojo, J.; Pirker, C.; Pichler, J.; Weis, S.; Kumar, R.; Webersinke, G.; et al. TERT promoter mutations are associated with poor prognosis and cell immortalization in meningioma. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 1584–1593.

- Sahm, F.; Schrimpf, D.; Olar, A.; Koelsche, C.; Reuss, D.; Bissel, J.; Kratz, A.; Capper, D.; Schefzyk, S.; Hielscher, T.; et al. TERT promoter mutations and risk of recurrence in meningioma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108, djv370.

- Lee, D.D.; Leão, R.; Komosa, M.; Gallo, M.; Zhang, C.H.; Lipman, T.; Remke, M.; Heidari, A.; Nunes, N.M.; Apolónio, J.; et al. DNA hypermethylation within TERT promoter upregulates TERT expression in cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 223–229.

- Dilley, R.L.; Greenberg, R.A. Alternative telomere maintenance and cancer. Trends Cancer 2015, 1, 145–156.

- Henson, J.D.; Hannay, J.A.; McCarthy, S.W.; Royds, J.A.; Yeager, T.R.; Robinson, R.A.; Wharton, S.B.; Jellinek, D.A.; Arbuckle, S.M.; Yoo, J.; et al. A robust assay for alternative lengthening of telomeres in tumors shows the significance of alternative lengthening of telomeres in sarcomas and astrocytomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 217–225.

- Liau, J.Y.; Lee, J.C.; Tsai, J.H.; Yang, C.Y.; Liu, T.L.; Ke, Z.L.; Hsu, H.H.; Jeng, Y.M. Comprehensive screening of alternative lengthening of telomeres phenotype and loss of telomeres phenotype and loss of ATRX expression in sarcomas. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 1545–1554.

- Lee, J.C.; Jeng, Y.M.; Liau, J.Y.; Tsai, J.H.; Hsu, H.H.; Yang, C.Y. Alternative lengthening of telomeres and loss of ATRX are frequent events in pleomorphic and dedifferentiated liposarcomas. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 1064–1073.

- Neumann, A.A.; Watson, C.M.; Noble, J.R.; Pickett, H.A.; Tam, P.P.; Reddel, R.R. Alternative lengthening of telomeres in normal mammalian somatic cells. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 18–23.

- Coluzzi, E.; Buonsante, R.; Leone, S.; Asmar, A.J.; Miller, K.L.; Cimini, D.; Sgura, A. Transient ALT activation protects human primary cells from chromosome instability induced by low chronic oxidative stress. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43309.

- De Vitis, M.; Berardinelli, F.; Coluzzi, E.; Marinaccio, J.; O’Sullivan, R.J.; Sgura, A.A. X-rays activate telomeric homologous recombination mediated repair in primary cells. Cells 2019, 8, 708.

- Pezzolo, A.; Pistorio, A.; Gambini, C.; Haupt, R.; Ferraro, M.; Erminio, G.; De Bernardi, B.; Garaventa, A.; Pistoia, V. Intratumoral diversity of telomere length in individual neuroblastoma tumors. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7493–7503.

- Gocha, A.R.; Nuovo, G.; Iwenofu, O.H.; Groden, J. Human sarcomas are mosaic for telomerase-dependent and telomerase-independent telomere maintenance mechanisms: Implications for telomere-based therapies. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 182, 41–48.

- Huang, Y.; Liang, P.; Liu, D.; Huang, J.; Songyang, Z. Telomere regulation in pluripotent stem cells. Protein Cell 2014, 5, 194–202.

- Liu, L. Linking Telomere Regulation to Stem Cell Pluripotency. Trends Genet. 2017, 33, 16–33.

- Perrem, K.; Colgin, L.M.; Neumann, A.A.; Yeager, T.R.; Reddel, R.R. Coexistence of alternative lengthening of telomeres and telomerase in hTERT- transfected GM847 cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 3862–3875.

- Episkopou, H.; Draskovic, I.; VanBeneden, A.; Tilman, G.; Mattiussi, M.; Gobin, M.; Arnoult, N.; Londoño-Vallejo, A.; Decottignies, A. Decottignies A: Alternative lengthening of telomeres is characterized by reduced compaction of telomeric chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 4391–4405.

- Episkopou, H.; Diman, A.; Claude, E.; Viceconte, N.; Decottignies, A. TSPYL5 depletion induces specific death of ALT cells through USP7-dependent proteasomal degradation of POT1. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 469–482.

- Tilman, G.; Loriot, A.; VanBeneden, A.; Arnoult, N.; Londono-Vallejo, J.A.; DeSmet, C.; Decottignies, A. Subtelomeric DNA hypomethylation is not required for telomeric sister chromatid exchanges in ALT cells. Oncogene 2009, 28, 1682–1693.

- Bechter, O.E.; Zou, Y.; Walker, W.; Wright, W.E.; Shay, J.W. Telomeric recombination in mismatch repair deficient human colon cancer cells after telomerase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 3444–3451.