Video Upload Options

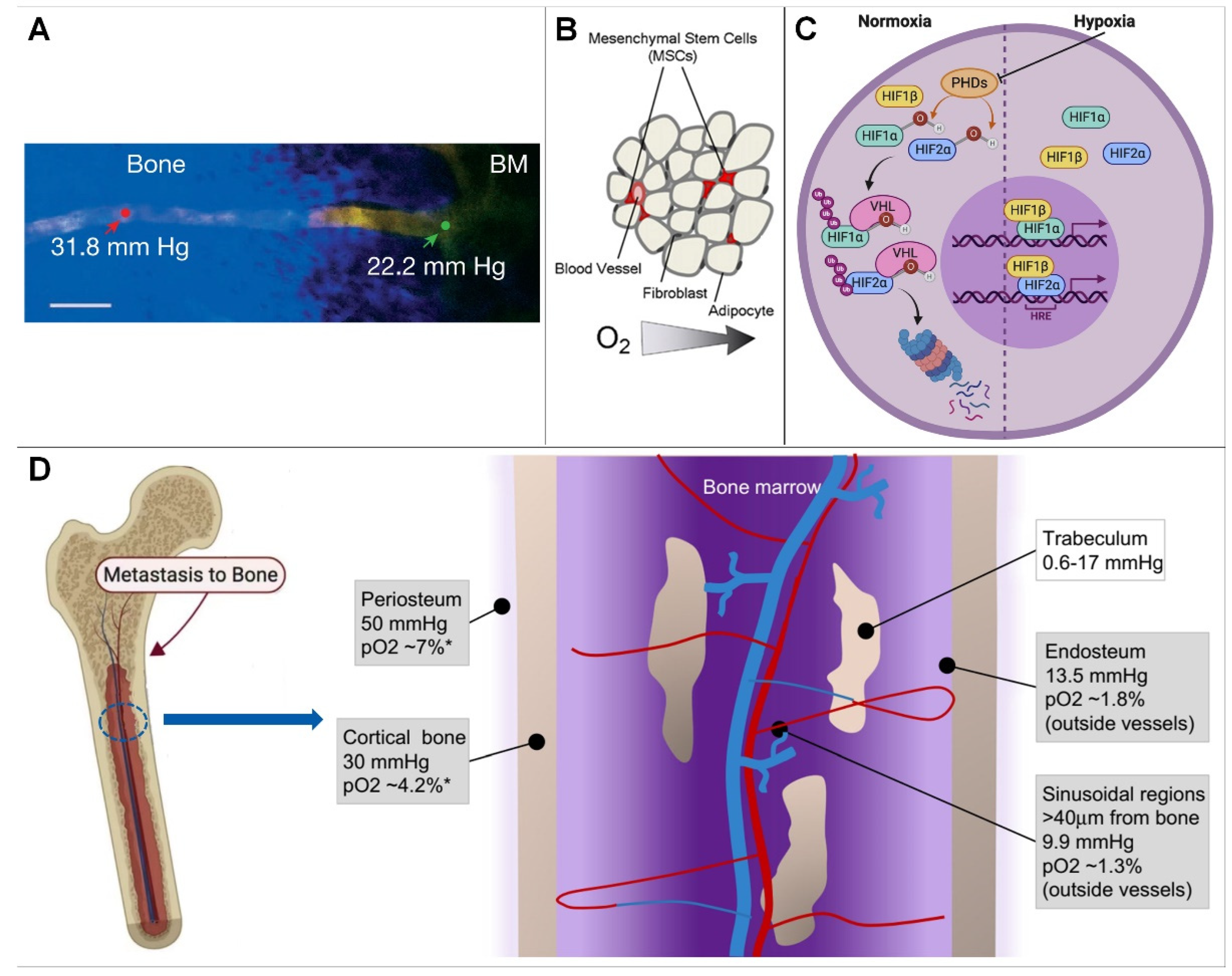

The normal physiological activities and functions of bone cells cannot be separated from the balance of the oxygenation level, and the physiological activities of bone cells are different under different oxygenation levels. At present, in vitro cell cultures are generally performed in a normoxic environment, and the partial pressure of oxygen of a conventional incubator is generally set at 141 mmHg (18.6%, close to the 20.1% oxygen in ambient air). This value is higher than the mean value of the oxygen partial pressure in human bone tissue. Additionally, the further away from the endosteal sinusoids, the lower the oxygen content. It follows that the construction of a hypoxic microenvironment is the key point of in vitro experimental investigation.

1. Introduction

2. The Hypoxic Microenvironment of Bone

2.1. Overview of the Bone Hypoxic Microenvironment

2.1.1. Hypoxic Microenvironment Characteristics of Bone

2.1.2. Causes of Bone Hypoxic Microenvironment Generation

2.2. Effect of Hypoxia on Bone Function

2.2.1. How Do Cells Sense Hypoxia?

- (1)

-

In a hypoxic environment, HIF-α levels are elevated, resulting in the nuclear β dimerization of subunits. HIF-1 is an HIF-1 β and HIF-1 α of a heterodimeric protein complex that, upon binding to RNA polymerase II and interaction with major transcriptional coactivators such as P300, promotes the transcription of target genes. At the same time, it affects the expression levels of erythropoietin, glucose transporters, glycolytic enzymes, vascular endothelial growth factor, and other proteins, which ultimately help to increase oxygen delivery or promote metabolic adaptation to hypoxia, thereby regulating many important physiological behaviors, such as cell metabolism, erythropoiesis, and local angiogenesis [21][27].

- (2)

-

Under normoxic conditions, inhibition of the asparagine hydroxylase factor hypoxia-1 transactivates the HIF-α of the conserved asparagine residues hydroxylated and interacts with P300 to ultimately repress HIF-induced transcription. HIF-3 α is thought to work by interacting with HIF-1 α competitive binding to inhibit HIF-1 α and HIF-2 β function [28]. Among these enzymes, PHD2 exerts major physiological functions. HIF-α is ubiquitinated and degraded by the ubiquitin protease tumor suppressor protein, resulting in reduced intracellular HIF levels, and, at the same time, a hypoxic environment can cause HIF-α levels to become elevated and associated with those in the nucleus β subunits undergoing dimerization [29][30][31]. Thereby, researchers can explore therapies for related diseases, such as ischemia, cancer, diabetes, stroke, infection, wound healing, and heart failure, by targeting the oxygen-sensing pathway.

2.2.2. Effect of Hypoxia on Bone Function

-

Hypoxia on cell differentiation

-

Hypoxia on skeleton development

-

Bone remodeling

-

Osteoimmunology

2.2.3. Hypoxia and Bone-Related Diseases

-

Tumor bone metastasis

-

Repair of bone defect

-

Osteoporosis

References

- Mohyeldin, A.; Garzon-Muvdi, T.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: A critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem. Cell 2010, 7, 150–161.

- Spencer, J.A.; Ferraro, F.; Roussakis, E.; Klein, A.; Wu, J.; Runnels, J.M.; Zaher, W.; Mortensen, L.J.; Alt, C.; Turcotte, R.; et al. Direct measurement of local oxygen concentration in the bone marrow of live animals. Nature 2014, 508, 269–273.

- Chow, D.C.; Wenning, L.A.; Miller, W.M.; Papoutsakis, E.T. Modeling pO2 distributions in the bone marrow hematopoietic compartment. I. Krogh’s model. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 675–684.

- Harrison, J.S.; Rameshwar, P.; Chang, V.; Bandari, P. Oxygen saturation in the bone marrow of healthy volunteers. Blood 2002, 99, 394.

- Johnson, R.W.; Sowder, M.E.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxia and Bone Metastatic Disease. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2017, 15, 231–238.

- Bhaskar, A.; Tiwary, B.N. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha and multiple myeloma. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 706–715.

- Toth, R.K.; Tran, J.D.; Muldong, M.T.; Nollet, E.A.; Schulz, V.V.; Jensen, C.C.; Hazlehurst, L.A.; Corey, E.; Durden, D.; Jamieson, C.; et al. Hypoxia-induced PIM kinase and laminin-activated integrin α6 mediate resistance to PI3K inhibitors in bone-metastatic CRPC. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2019, 7, 297–312.

- Rankin, E.B.; Giaccia, A.J.; Schipani, E. A central role for hypoxic signaling in cartilage, bone, and hematopoiesis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2011, 9, 46–52.

- Alvarez-Martins, I.; Remedio, L.; Matias, I.; Diogo, L.N.; Monteiro, E.C.; Dias, S. The impact of chronic intermittent hypoxia on hematopoiesis and the bone marrow microenvironment. Pflug. Arch. 2016, 468, 919–932.

- Bendinelli, P.; Maroni, P.; Matteucci, E.; Desiderio, M.A. Cell and Signal Components of the Microenvironment of Bone Metastasis Are Affected by Hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 706.

- Gruneboom, A.; Hawwari, I.; Weidner, D.; Culemann, S.; Muller, S.; Henneberg, S.; Brenzel, A.; Merz, S.; Bornemann, L.; Zec, K.; et al. A network of trans-cortical capillaries as mainstay for blood circulation in long bones. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 236–250.

- Falank, C.; Fairfield, H.; Reagan, M.R. Signaling Interplay between Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue and Multiple Myeloma cells. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 67.

- Hiraga, T. Hypoxic Microenvironment and Metastatic Bone Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3523.

- Hiraga, T. Bone metastasis: Interaction between cancer cells and bone microenvironment. J. Oral. Biosci. 2019, 61, 95–98.

- Chow, D.C.; Wenning, L.A.; Miller, W.M.; Papoutsakis, E.T. Modeling pO2 distributions in the bone marrow hematopoietic compartment. II. Modified Kroghian models. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 685–696.

- Semenza, G.L. The hypoxic tumor microenvironment: A driving force for breast cancer progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 382–391.

- Zahm, A.M.; Bucaro, M.A.; Ayyaswamy, P.S.; Srinivas, V.; Shapiro, I.M.; Adams, C.S.; Mukundakrishnan, K. Numerical modeling of oxygen distributions in cortical and cancellous bone: Oxygen availability governs osteonal and trabecular dimensions. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010, 299, C922–C929.

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, S.K.; Jung, B.J.; Choi, S.B.; Choi, E.Y.; Kim, C.S. Enhancing proliferation and optimizing the culture condition for human bone marrow stromal cells using hypoxia and fibroblast growth factor-2. Stem. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 87–95.

- Ohyashiki, J.H.; Umezu, T.; Ohyashiki, K. Exosomes promote bone marrow angiogenesis in hematologic neoplasia: The role of hypoxia. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2016, 23, 268–273.

- Peck, S.H.; Bendigo, J.R.; Tobias, J.W.; Dodge, G.R.; Malhotra, N.R.; Mauck, R.L.; Smith, L.J. Hypoxic Preconditioning Enhances Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Survival in a Low Oxygen and Nutrient-Limited 3D Microenvironment. Cartilage 2021, 12, 512–525.

- De Bels, D.; Corazza, F.; Balestra, C. Oxygen sensing, homeostasis, and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1845.

- Eliasson, P.; Jonsson, J.I. The hematopoietic stem cell niche: Low in oxygen but a nice place to be. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010, 222, 17–22.

- Taheem, D.K.; Jell, G.; Gentleman, E. Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1alpha in Osteochondral Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Part B. Rev. 2020, 26, 105–115.

- Stegen, S.; Carmeliet, G. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible transcription factors and oxygen-sensing prolyl hydroxylases in bone development and homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2019, 28, 328–335.

- Todd, V.M.; Johnson, R.W. Hypoxia in bone metastasis and osteolysis. Cancer Lett. 2020, 489, 144–154.

- Teh, S.W.; Koh, A.E.; Tong, J.B.; Wu, X.; Samrot, A.V.; Rampal, S.; Mok, P.L.; Subbiah, S.K. Hypoxia in Bone and Oxygen Releasing Biomaterials in Fracture Treatments Using Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy: A Review. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 634131.

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 2012, 148, 399–408.

- Kim, E.J.; Yoo, Y.G.; Yang, W.K.; Lim, Y.S.; Na, T.Y.; Lee, I.K.; Lee, M.O. Transcriptional activation of HIF-1 by RORalpha and its role in hypoxia signaling. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 1796–1802.

- Xu, C.; Liu, X.; Zha, H.; Fan, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Xiao, W. A pathogen-derived effector modulates host glucose metabolism by arginine GlcNAcylation of HIF-1alpha protein. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007259.

- Wan, C.; Shao, J.; Gilbert, S.R.; Riddle, R.C.; Long, F.; Johnson, R.S.; Schipani, E.; Clemens, T.L. Role of HIF-1alpha in skeletal development. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1192, 322–326.

- Camacho-Cardenosa, M.; Camacho-Cardenosa, A.; Timon, R.; Olcina, G.; Tomas-Carus, P.; Brazo-Sayavera, J. Can Hypoxic Conditioning Improve Bone Metabolism? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 1799.

- Parrinello, S.; Samper, E.; Krtolica, A.; Goldstein, J.; Melov, S.; Campisi, J. Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 741–747.

- Lennon, D.P.; Edmison, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Cultivation of rat marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in reduced oxygen tension: Effects on in vitro and in vivo osteochondrogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2001, 187, 345–355.

- D’Ippolito, G.; Diabira, S.; Howard, G.A.; Roos, B.A.; Schiller, P.C. Low oxygen tension inhibits osteogenic differentiation and enhances stemness of human MIAMI cells. Bone 2006, 39, 513–522.

- Fink, T.; Abildtrup, L.; Fogd, K.; Abdallah, B.M.; Kassem, M.; Ebbesen, P.; Zachar, V. Induction of adipocyte-like phenotype in human mesenchymal stem cells by hypoxia. Stem Cells 2004, 22, 1346–1355.

- Ren, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Zhou, C.; Liao, L.; Jia, M.; Zhao, Q.; Cai, H.; Han, Z.C.; et al. Proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells under hypoxic conditions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 347, 12–21.

- Usategui-Martin, R.; Rigual, R.; Ruiz-Mambrilla, M.; Fernandez-Gomez, J.M.; Duenas, A.; Perez-Castrillon, J.L. Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Hypoxia-Induced Alterations in Bone Remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3233.

- Gorissen, B.; de Bruin, A.; Miranda-Bedate, A.; Korthagen, N.; Wolschrijn, C.; de Vries, T.J.; van Weeren, R.; Tryfonidou, M.A. Hypoxia negatively affects senescence in osteoclasts and delays osteoclastogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 414–426.

- Yang, C.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, F.; Chen, Z.; Su, P.; Li, Y.; Qian, A. Bone Microenvironment and Osteosarcoma Metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6985.

- Gala, D.N.; Fabian, Z. To Breathe or Not to Breathe: The Role of Oxygen in Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Senescence. Stem. Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 8899756.

- Ikeda, S.; Tagawa, H. Impact of hypoxia on the pathogenesis and therapy resistance in multiple myeloma. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 3995–4004.

- Li, L.; Li, A.; Zhu, L.; Gan, L.; Zuo, L. Roxadustat promotes osteoblast differentiation and prevents estrogen deficiency-induced bone loss by stabilizing HIF-1alpha and activating the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 286.

- Owen-Woods, C.; Kusumbe, A. Fundamentals of bone vasculature: Specialization, interactions and functions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 123, 36–47.

- Gu, H.; Ru, Y.; Wang, W.; Cai, G.; Gu, L.; Ye, J.; Zhang, W.B.; Wang, L. Orexin-A Reverse Bone Mass Loss Induced by Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia Through OX1R-Nrf2/HIF-1alpha Pathway. Drug. Des. Devel Ther. 2022, 16, 2145–2160.

- Shang, T.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.; Cui, L.; Guo, F.F. Hypoxia promotes differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells into endothelial cells through demethylation of ephrinB2. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 133.

- Sheng, L.; Mao, X.; Yu, Q.; Yu, D. Effect of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway on hypoxia-induced proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 55–62.

- Zhang, Y.; Hao, Z.; Wang, P.; Xia, Y.; Wu, J.; Xia, D.; Fang, S.; Xu, S. Exosomes from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells enhance fracture healing through HIF-1alpha-mediated promotion of angiogenesis in a rat model of stabilized fracture. Cell Prolif. 2019, 52, e12570.

- Bai, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Xiao, Y.; Bao, C. HIF signaling: A new propellant in bone regeneration. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 138, 212874.

- Chen, K.; Zhao, J.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, L.; Yang, K.; Chang, L.; Jia, P.; Qi, J.; Deng, L.; Li, C. Osteocytic HIF-1alpha Pathway Manipulates Bone Micro-structure and Remodeling via Regulating Osteocyte Terminal Differentiation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 721561.

- Ceradini, D.J.; Kulkarni, A.R.; Callaghan, M.J.; Tepper, O.M.; Bastidas, N.; Kleinman, M.E.; Capla, J.M.; Galiano, R.D.; Levine, J.P.; Gurtner, G.C. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 858–864.

- Ma, Y.; Qiu, S.; Zhou, R. Osteoporosis in Patients With Respiratory Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 939253.

- Merceron, C.; Ranganathan, K.; Wang, E.; Tata, Z.; Makkapati, S.; Khan, M.P.; Mangiavini, L.; Yao, A.Q.; Castellini, L.; Levi, B.; et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha is a negative regulator of osteoblastogenesis and bone mass accrual. Bone Res. 2019, 7, 7.

- Kimura, H.; Ota, H.; Kimura, Y.; Takasawa, S. Effects of Intermittent Hypoxia on Pulmonary Vascular and Systemic Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 3101.

- Mylonis, I.; Simos, G.; Paraskeva, E. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors and the Regulation of Lipid Metabolism. Cells 2019, 8, 214.

- Ehrnrooth, E.; von der Maase, H.; Sørensen, B.S.; Poulsen, J.H.; Horsman, M.R. The ability of hypoxia to modify the gene expression of thymidylate synthase in tumour cells in vivo. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1999, 75, 885–891.

- Shu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Z.; Cai, J.; Tang, C.; Dong, Z. Hypoxia and Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Kidney Injury and Repair. Cells 2019, 8, 207.

- Wu, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Han, Y.; Lu, L.; Yang, K.; Cao, J. Effect of HIF-1alpha/miR-10b-5p/PTEN on Hypoxia-Induced Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e011948.

- Norris, P.C.; Libreros, S.; Serhan, C.N. Resolution metabolomes activated by hypoxic environment. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax4895.

- Chicana, B.; Donham, C.; Millan, A.J.; Manilay, J.O. Wnt Antagonists in Hematopoietic and Immune Cell Fate: Implications for Osteoporosis Therapies. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2019, 17, 49–58.

- Deynoux, M.; Sunter, N.; Herault, O.; Mazurier, F. Hypoxia and Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Leukemias. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 41.

- Reagan, M.R.; Rosen, C.J. Navigating the bone marrow niche: Translational insights and cancer-driven dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 154–168.

- De Spiegelaere, W.; Cornillie, P.; Casteleyn, C.; Burvenich, C.; Van den Broeck, W. Detection of hypoxia inducible factors and angiogenic growth factors during foetal endochondral and intramembranous ossification. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2010, 39, 376–384.

- Robins, J.C.; Akeno, N.; Mukherjee, A.; Dalal, R.R.; Aronow, B.J.; Koopman, P.; Clemens, T.L. Hypoxia induces chondrocyte-specific gene expression in mesenchymal cells in association with transcriptional activation of Sox9. Bone 2005, 37, 313–322.

- Byrne, N.M.; Summers, M.A.; McDonald, M.M. Tumor Cell Dormancy and Reactivation in Bone: Skeletal Biology and Therapeutic Opportunities. JBMR Plus 2019, 3, e10125.

- Zhuang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, M.; Li, M.; Si, J.; Lin, K.; Yu, H. HIF-1alpha Regulates Osteogenesis of Periosteum-Derived Stem Cells Under Hypoxia Conditions via Modulating POSTN Expression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 836285.

- Senel, K.; Baykal, T.; Seferoglu, B.; Altas, E.U.; Baygutalp, F.; Ugur, M.; Kiziltunc, A. Circulating vascular endothelial growth factor concentrations in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Arch. Med. Sci. 2013, 9, 709–712.