| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kenneth Nugent | -- | 4752 | 2023-04-28 03:33:26 |

Video Upload Options

The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated vaccine have highlighted vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers (HCWs). Vaccine hesitancy among this group existed prior to the pandemic and particularly centered around influenza vaccination. Being a physician, having more advanced education, and previous vaccination habits are frequently associated with vaccine acceptance. Reasons for hesitancy include concerns about safety and efficacy, mistrust of government and institutions, waiting for more data, and feeling that personal rights are being infringed upon.

1. Introduction

2. Pre-COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers

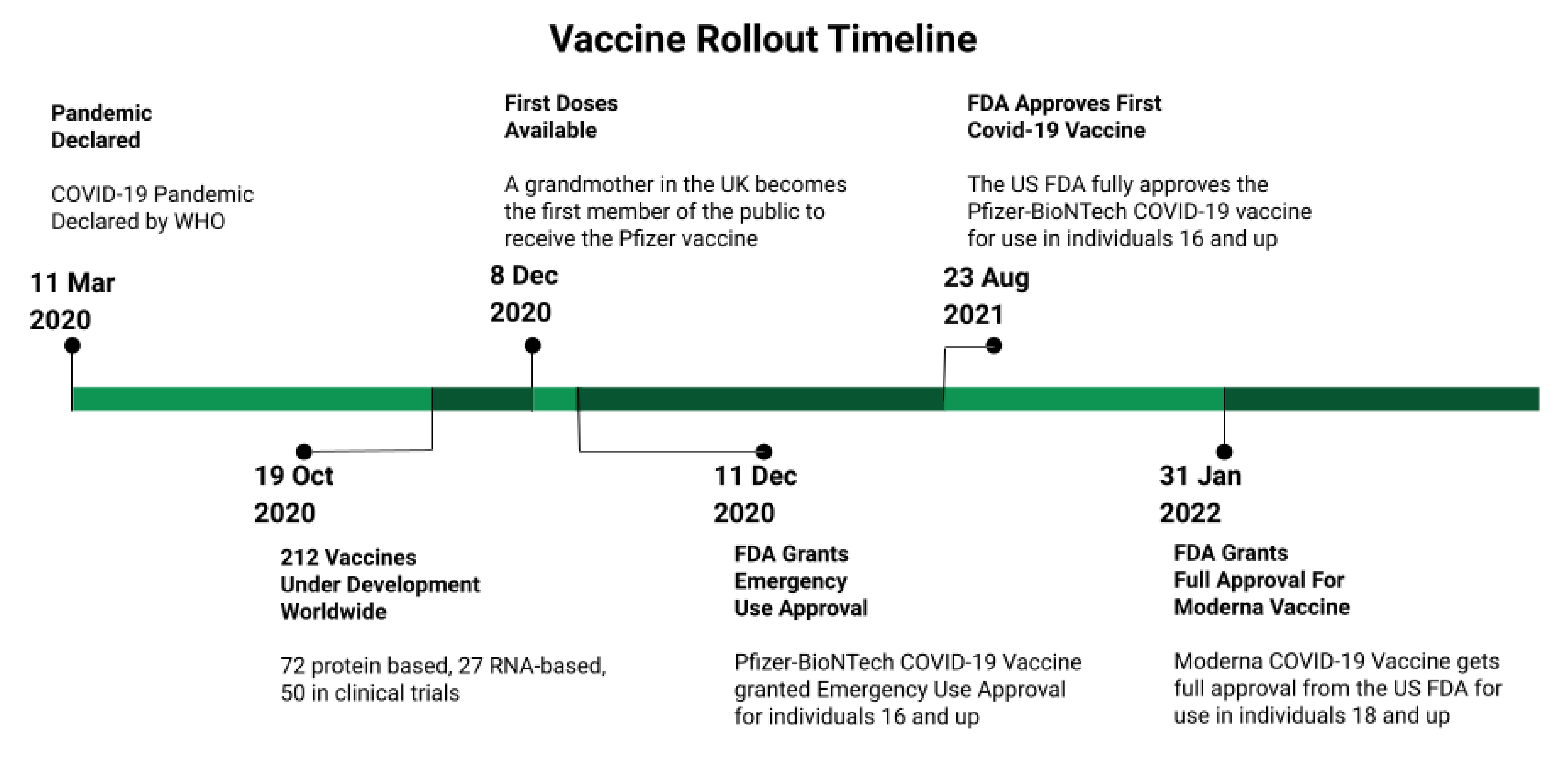

3. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Vaccine Development

4. Demographics of Vaccine Hesitant HCWs

5. Reasons for Hesitancy

|

Author |

Survey Date |

Country |

Participants Number |

Response |

Author’s Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Verger [53] |

October–November 2020 |

France, Belgium, Canada |

2678 (Physicians and Nurses) |

48.6%—high acceptance 23.0%—moderate acceptance 28.4%—hesitancy or reluctance Main concern- safety |

Must build trust about efficacy and safety |

|

Biswas [99] |

February 2020–January 2021 35 different studies |

Worldwide |

HCW 76,741 |

22.51% hesitant Range 4.3–72.0% Main concerns: side effects, safety, efficacy |

Education and policy-based interventions are needed to ensure vaccination |

|

Meyer [139] |

December 2020 |

United States |

HCW 16,292 |

55.3% will receive 16.3% will not 28.4 % unsure Intentions to receive increased after EUA recommendation |

Highly visible information from experts may increase intent |

|

Pal [140] |

February–March 2021 |

United States |

HCW 1374 |

7.9% hesitant Mistrust important factor 83.6% would accept an annual booster |

Concerns about safety and efficacy and lack of trust underlie hesitancy |

|

Bell [103] |

January 2021 |

United Kingdom |

HCW SCW 1917 |

6.6% declined vaccine offer Complex analysis of characteristics of participants |

Authors offer detailed policy recommendations |

|

Woolf [141] |

April–June 2021 |

United Kingdom |

HCW 5633 total 3235 answered free text question |

18% favored mandatory vaccination |

Building trust with education and support may be effective with hesitant HCW |

|

Janssen [81] |

December 2020–March 2021 |

France |

4349 HCWs |

Online survey presenting hypothetical scenarios for efficacy, longevity, and adverse events. Quantified the effect of each on willingness. |

Fear of adverse events was main concern, hesitancy decreased with time. Reassurance about adverse events is important. |

|

Choi [142] |

March–May 2021 |

United States |

2948 HCWs surveyed, with semi-structured interviews |

Nurses less likely than physicians to see vaccine as safe or effective. Many claiming vaccines unnecessary or unsafe. |

Stressed education and mandates |

HCW—health care workers, SCW—social care workers, EUA—emergency use authorization.

References

- Haeder, S.F. Joining the herd? U.S. public opinion and vaccination requirements across educational settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2375–2385.

- Smith, T.C. Vaccine Rejection and Hesitancy: A Review and Call to Action. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017, 4, ofx146.

- Klompas, M.; Pearson, M.; Morris, C. The Case for Mandating COVID-19 Vaccines for Health Care Workers. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 1305–1307.

- Dubé, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J.A. Vaccine hesitancy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773.

- Hakim, M.S. SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, and the debunking of conspiracy theories. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, e2222.

- Ullah, I.; Khan, K.S.; Tahir, M.J.; Ahmed, A.; Harapan, H. Myths and conspiracy theories on vaccines and COVID-19: Potential effect on global vaccine refusals. Vacunas 2021, 22, 93–97.

- Giubilini, A. Vaccination ethics. Br. Med. Bull. 2020, 137, 4–12.

- Paterson, P.; Meurice, F.; Stanberry, L.R.; Glismann, S.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Larson, H.J. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine 2016, 34, 6700–6706.

- Schmid, P.; Rauber, D.; Betsch, C.; Lidolt, G.; Denker, M.-L. Barriers of Influenza Vaccination Intention and Behavior—A Systematic Review of Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy, 2005–2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170550.

- Hollmeyer, H.; Hayden, F.; Mounts, A.; Buchholz, U. Review: Interventions to increase influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in hospitals. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2013, 7, 604–621.

- Da Costa, V.G.; Saivish, M.V.; Santos, D.E.R.; de Lima Silva, R.F.; Moreli, M.L. Comparative epidemiology between the 2009 H1N1 influenza and COVID-19 pandemics. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1797–1804.

- Fabry, P.; Gagneur, A.; Pasquier, J.-C. Determinants of A (H1N1) vaccination: Cross-sectional study in a population of pregnant women in Quebec. Vaccine 2011, 29, 1824–1829.

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A. Willingness of health care workers of various nationalities to accept H1N1 (2009) pandemic influenza A vaccination. Ann. Saudi Med. 2012, 32, 64–67.

- Blasi, F.; Aliberti, S.; Mantero, M.; Centanni, S. Compliance with anti-H1N1 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 37–41.

- Grohskopf, L.A.; Alyanak, E.; Broder, K.R.; Blanton, L.H.; Fry, A.M.; Jernigan, D.B.; Atmar, R.L. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020–2021 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2020, 69, 1–24.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD). Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Health Care Personnel—United States, 2020–2021 Influenza Season; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- Wilde, J.A.; McMillan, J.A.; Serwint, J.; Butta, J.; O’Riordan, M.A.; Steinhoff, M.C. Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccine in Health Care ProfessionalsA Randomized Trial. JAMA 1999, 281, 908–913.

- Potter, J.; Stott, D.J.; Roberts, M.A.; Elder, A.G.; O’Donnell, B.; Knight, P.V.; Carman, W.F. Influenza Vaccination of Health Care Workers in Long-Term-Care Hospitals Reduces the Mortality of Elderly Patients. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 175, 1–6.

- Carman, W.F.; Elder, A.G.; Wallace, L.A.; McAulay, K.; Walker, A.; Murray, G.D.; Stott, D.J. Effects of influenza vaccination of health-care workers on mortality of elderly people in long-term care: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000, 355, 93–97.

- Ahmed, F.; Lindley, M.C.; Allred, N.; Weinbaum, C.M.; Grohskopf, L. Effect of Influenza Vaccination of Healthcare Personnel on Morbidity and Mortality Among Patients: Systematic Review and Grading of Evidence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 58, 50–57.

- Hayward, A.C.; Harling, R.; Wetten, S.; Johnson, A.M.; Munro, S.; Smedley, J.; Murad, S.; Watson, J.M. Effectiveness of an influenza vaccine programme for care home staff to prevent death, morbidity, and health service use among residents: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2006, 333, 1241.

- Van den Dool, C.; Bonten, M.J.M.; Hak, E.; Heijne, J.C.M.; Wallinga, J. The Effects of Influenza Vaccination of Health Care Workers in Nursing Homes: Insights from a Mathematical Model. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e200.

- De Serres, G.; Skowronski, D.M.; Ward, B.J.; Gardam, M.; Lemieux, C.; Yassi, A.; Patrick, D.M.; Krajden, M.; Loeb, M.; Collignon, P.; et al. Influenza Vaccination of Healthcare Workers: Critical Analysis of the Evidence for Patient Benefit Underpinning Policies of Enforcement. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0163586.

- Hayward, A.C. Influenza Vaccination of Healthcare Workers Is an Important Approach for Reducing Transmission of Influenza from Staff to Vulnerable Patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169023.

- Haviari, S.; Bénet, T.; Saadatian-Elahi, M.; André, P.; Loulergue, P.; Vanhems, P. Vaccination of healthcare workers: A review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2015, 11, 2522–2537.

- Committee On Infectious, D.; Byington, C.L.; Maldonado, Y.A.; Barnett, E.D.; Davies, H.D.; Edwards, K.M.; Lynfield, R.; Munoz, F.M.; Nolt, D.L.; Nyquist, A.-C.; et al. Influenza Immunization for All Health Care Personnel: Keep It Mandatory. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 809–818.

- Desilver, D. States Have Mandated Vaccinations since Long before COVID-19. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/10/08/states-have-mandated-vaccinations-since-long-before-covid-19/ (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Poland, G.A.; Tosh, P.; Jacobson, R.M. Requiring influenza vaccination for health care workers: Seven truths we must accept. Vaccine 2005, 23, 2251–2255.

- Gesser-Edelsburg, A.; Badarna Keywan, H. Physicians’ Perspective on Vaccine-Hesitancy at the Beginning of Israel’s COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign and Public’s Perceptions of Physicians’ Knowledge When Recommending the Vaccine to Their Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 855468.

- Rodger, D.; Blackshaw, B.P. COVID-19 Vaccination Should not be Mandatory for Health and Social Care Workers. New Bioeth 2022, 28, 27–39.

- Song, Y.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L.; Yi, B.; Hao, X.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, R.; Greene, C. Increasing seasonal influenza vaccination among high risk groups in China: Do community healthcare workers have a role to play? Vaccine 2017, 35, 4060–4063.

- Lorenc, T.; Marshall, D.; Wright, K.; Sutcliffe, K.; Sowden, A. Seasonal influenza vaccination of healthcare workers: Systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 732.

- Pereira, M.; Williams, S.; Restrick, L.; Cullinan, P.; Hopkinson, N.S. Barriers to influenza vaccination in healthcare workers. BMJ 2018, 360, k1141.

- Stewart, A.M. Mandatory Vaccination of Health Care Workers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 2015–2017.

- Bechini, A.; Lorini, C.; Zanobini, P.; Mandò Tacconi, F.; Boccalini, S.; Grazzini, M.; Bonanni, P.; Bonaccorsi, G. Utility of Healthcare System-Based Interventions in Improving the Uptake of Influenza Vaccination in Healthcare Workers at Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2020, 8, 165.

- Stevenson, C.G.; McArthur, M.A.; Naus, M.; Abraham, E.; McGeer, A.J. Prevention of influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia in Canadian long-term care facilities: How are we doing? Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2001, 164, 1413–1419.

- Thomas, R.E.; Jefferson, T.; Lasserson, T.J. Influenza vaccination for healthcare workers who care for people aged 60 or older living in long-term care institutions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD005187.

- Talbot, T.R.; Schimmel, R.; Swift, M.D.; Rolando, L.A.; Johnson, R.T.; Muscato, J.; Sternberg, P.; Dubree, M.; McGown, P.W.; Yarbrough, M.I.; et al. Expanding mandatory healthcare personnel immunization beyond influenza: Impact of a broad immunization program with enhanced accountability. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021, 42, 513–518.

- Karlsson, L.C.; Lewandowsky, S.; Antfolk, J.; Salo, P.; Lindfelt, M.; Oksanen, T.; Kivimäki, M.; Soveri, A. The association between vaccination confidence, vaccination behavior, and willingness to recommend vaccines among Finnish healthcare workers. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224330.

- Petek, D.; Kamnik-Jug, K. Motivators and barriers to vaccination of health professionals against seasonal influenza in primary healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 853.

- Hollmeyer, H.G.; Hayden, F.; Poland, G.; Buchholz, U. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospitals--a review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine 2009, 27, 3935–3944.

- Rhudy, L.M.; Tucker, S.J.; Ofstead, C.L.; Poland, G.A. Personal Choice or Evidence-Based Nursing Intervention: Nurses’ Decision-Making about Influenza Vaccination. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2010, 7, 111–120.

- Carvalho, T.; Krammer, F.; Iwasaki, A. The first 12 months of COVID-19: A timeline of immunological insights. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 245–256.

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, S.; Ou, J.; Zhang, J.; Lan, W.; Guan, W.; Wu, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wu, J.; et al. COVID-19: Coronavirus Vaccine Development Updates. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 602256.

- COVID-19 Vaccine R&D Investments. Available online: https://www.knowledgeportalia.org/covid19-r-d-funding (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Ball, P. The lightning-fast quest for COVID vaccines—And what it means for other diseases. Nature 2021, 589, 16–18.

- BBC News. COVID-19 Vaccine: First Person Receives Pfizer Jab in UK. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-55227325 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Bok, K.; Sitar, S.; Graham, B.S.; Mascola, J.R. Accelerated COVID-19 vaccine development: Milestones, lessons, and prospects. Immunity 2021, 54, 1636–1651.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- FDA. Spikevax and Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/spikevax-and-moderna-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Koontalay, A.; Suksatan, W.; Prabsangob, K.; Sadang, J.M. Healthcare Workers’ Burdens During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 3015–3025.

- Kwok, K.O.; Li, K.-K.; Wei, W.I.; Tang, A.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Lee, S.S. Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: A survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 114, 103854.

- Verger, P.; Scronias, D.; Dauby, N.; Adedzi, K.A.; Gobert, C.; Bergeat, M.; Gagneur, A.; Dubé, E. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: A survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2002047.

- Gagneux-Brunon, A.; Detoc, M.; Bruel, S.; Tardy, B.; Rozaire, O.; Frappe, P.; Botelho-Nevers, E. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: A cross-sectional survey. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 108, 168–173.

- Ledda, C.; Costantino, C.; Cuccia, M.; Maltezou, H.C.; Rapisarda, V. Attitudes of Healthcare Personnel towards Vaccinations before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 168–173.

- Fakonti, G.; Kyprianidou, M.; Toumbis, G.; Giannakou, K. Attitudes and Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination Among Nurses and Midwives in Cyprus: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 656138.

- Gharpure, R.; Guo, A.; Bishnoi, C.K.; Patel, U.; Gifford, D.; Tippins, A.; Jaffe, A.; Shulman, E.; Stone, N.; Mungai, E.; et al. Early COVID-19 First-Dose Vaccination Coverage Among Residents and Staff Members of Skilled Nursing Facilities Participating in the Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program—United States, December 2020-January 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 178–182.

- Reses, H.E.; Jones, E.S.; Richardson, D.B.; Cate, K.M.; Walker, D.W.; Shapiro, C.N. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among hospital-based healthcare personnel reported through the Department of Health and Human Services Unified Hospital Data Surveillance System, United States, January 20, 2021-September 15, 2021. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 1554–1557.

- Lee, J.T.; Althomsons, S.P.; Wu, H.; Budnitz, D.S.; Kalayil, E.J.; Lindley, M.C.; Pingali, C.; Bridges, C.B.; Geller, A.I.; Fiebelkorn, A.P.; et al. Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Among Health Care Personnel Working in Long-Term Care Facilities, by Job Category, National Healthcare Safety Network—United States, March 2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1036–1039.

- American Medical Association. AMA Survey Shows Over 96% of Doctors Fully Vaccinated against COVID-19. Available online: www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-survey-shows-over-96-doctors-fully-vaccinated-against-covid-19 (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Levy, R. How Many Health Care Workers Are Vaccinated? It’s Anyone’s Guess. Available online: https://www.politico.com/news/2022/01/19/health-care-workers-hospitals-vaccinated-527392 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

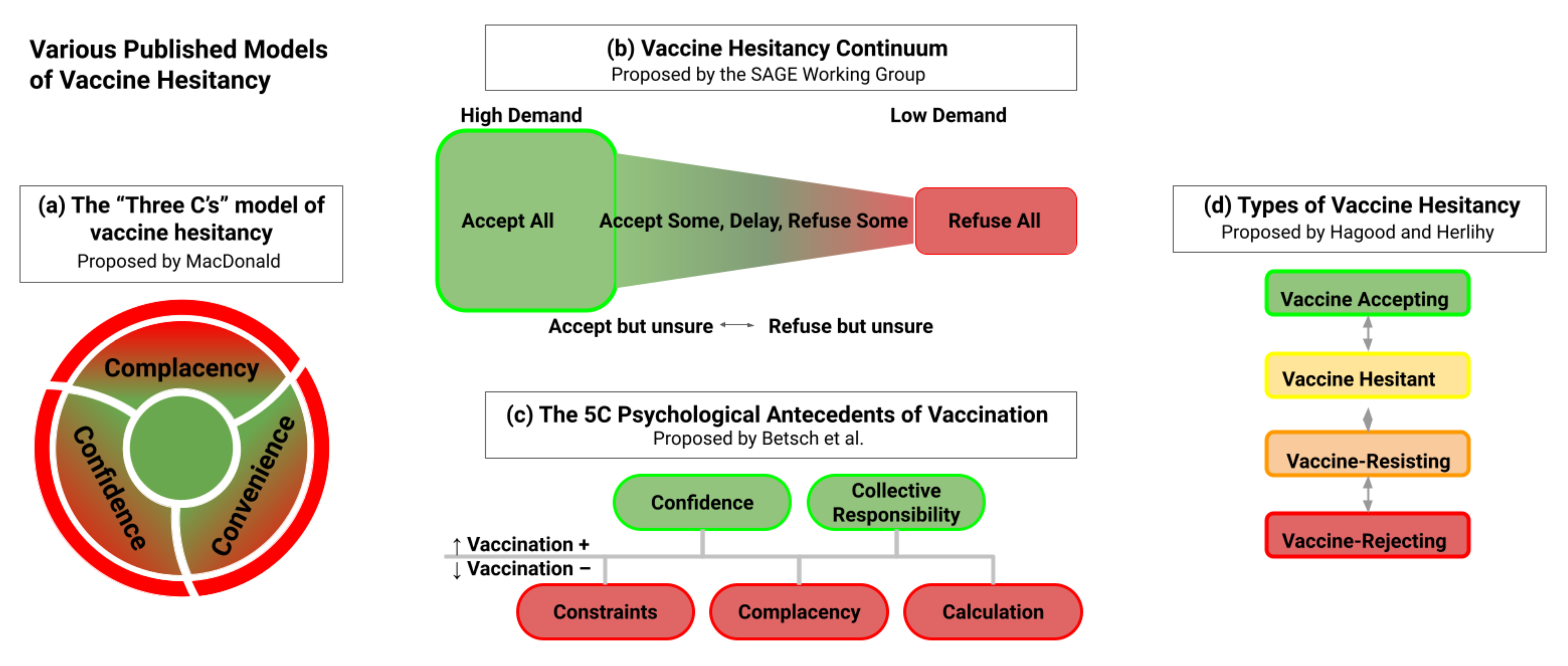

- Hagood, E.A.; Mintzer Herlihy, S. Addressing heterogeneous parental concerns about vaccination with a multiple-source model: A parent and educator perspective. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1790–1794.

- MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164.

- Betsch, C.; Schmid, P.; Heinemeier, D.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C.; Böhm, R. Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208601.

- Sage Working Group. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Ritchie, H.; Mathieu, E.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Beltekian, D.; Roser, M. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/ (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Kingori, P. No Jab, No Job? Ethical Issues in Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination of Healthcare Personnel. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004877.

- Federal Government of the United States. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Omnibus COVID-19 Health Care Staff Vaccination. A Rule by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 0938-AU75; Federal Government of the United States: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Waldman, S.E.; Buehring, T.; Escobar, D.J.; Gohil, S.K.; Gonzales, R.; Huang, S.S.; Olenslager, K.; Prabaker, K.K.; Sandoval, T.; Yim, J.; et al. Secondary Cases of Delta-Variant COVID-19 Among Vaccinated Healthcare Workers with Breakthrough Infections is Rare. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021, ciab916.

- Cabezas, C.; Coma, E.; Mora-Fernandez, N.; Li, X.; Martinez-Marcos, M.; Fina, F.; Fabregas, M.; Hermosilla, E.; Jover, A.; Contel, J.C.; et al. Associations of BNT162b2 vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospital admission and death with COVID-19 in nursing homes and healthcare workers in Catalonia: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2021, 374, n1868.

- Litigation Update for CMS Omnibus COVID-19 Health Care Staff Vaccination Interim Final Rule. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/Emergency/EPRO/Current-Emergencies/Current-Emergencies-page (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Gostin, L.O.; Parmet, W.E.; Rosenbaum, S. The US Supreme Court’s Rulings on Large Business and Health Care Worker Vaccine Mandates: Ramifications for the COVID-19 Response and the Future of Federal Public Health Protection. JAMA 2022, 327, 713–714.

- Center for Clinical Standards and Quality/Quality, S.O.G. Guidance for the Interim Final Rule—Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Omnibus COVID-19 Health Care Staff Vaccination; QSO-22-11-ALL; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Baltimore, MD, USA, 20 January 2022.

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779.

- Pacella-LaBarbara, M.L.; Park, Y.L.; Patterson, P.D.; Doshi, A.; Guyette, M.K.; Wong, A.H.; Chang, B.P.; Suffoletto, B.P. COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake and Intent Among Emergency Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 852–856.

- Qunaibi, E.; Basheti, I.; Soudy, M.; Sultan, I. Hesitancy of Arab Healthcare Workers towards COVID-19 Vaccination: A Large-Scale Multinational Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 446.

- Berry, S.D.; Johnson, K.S.; Myles, L.; Herndon, L.; Montoya, A.; Fashaw, S.; Gifford, D. Lessons learned from frontline skilled nursing facility staff regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 1140–1146.

- Harrison, J.; Berry, S.; Mor, V.; Gifford, D. “Somebody Like Me”: Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Staff in Skilled Nursing Facilities. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1133–1137.

- Shekhar, R.; Sheikh, A.B.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Kottewar, S.; Mir, H.; Barrett, E.; Pal, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Health Care Workers in the United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 119.

- Toth-Manikowski, S.M.; Swirsky, E.S.; Gandhi, R.; Piscitello, G. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among health care workers, communication, and policy-making. Am. J. Infect. Control 2022, 50, 20–25.

- Janssen, C.; Maillard, A.; Bodelet, C.; Claudel, A.-L.; Gaillat, J.; Delory, T.; on behalf of the ACV Alpin Study Group. Hesitancy towards COVID-19 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: A Multi-Centric Survey in France. Vaccines 2021, 9, 547.

- Dzieciolowska, S.; Hamel, D.; Gadio, S.; Dionne, M.; Gagnon, D.; Robitaille, L.; Cook, E.; Caron, I.; Talib, A.; Parkes, L.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and refusal among Canadian healthcare workers: A multicenter survey. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 1152–1157.

- Green-McKenzie, J.; Shofer, F.S.; Momplaisir, F.; Kuter, B.J.; Kruse, G.; Bilal, U.; Behta, M.; O’Donnell, J.; Al-Ramahi, N.; Kasbekar, N.; et al. Factors Associated With COVID-19 Vaccine Receipt by Health Care Personnel at a Major Academic Hospital During the First Months of Vaccine Availability. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2136582.

- Mohammed, R.; Nguse, T.M.; Habte, B.M.; Fentie, A.M.; Gebretekle, G.B. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Ethiopian healthcare workers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261125.

- Holzmann-Littig, C.; Braunisch, M.C.; Kranke, P.; Popp, M.; Seeber, C.; Fichtner, F.; Littig, B.; Carbajo-Lozoya, J.; Allwang, C.; Frank, T.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance and Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in Germany. Vaccines 2021, 9, 777.

- Yanez, N.D.; Weiss, N.S.; Romand, J.-A.; Treggiari, M.M. COVID-19 mortality risk for older men and women. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1742.

- Gadoth, A.; Halbrook, M.; Martin-Blais, R.; Gray, A.; Tobin, N.H.; Ferbas, K.G.; Aldrovandi, G.M.; Rimoin, A.W. Cross-sectional Assessment of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Among Health Care Workers in Los Angeles. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 882–885.

- Kara Esen, B.; Can, G.; Pirdal, B.Z.; Aydin, S.N.; Ozdil, A.; Balkan, I.I.; Budak, B.; Keskindemirci, Y.; Karaali, R.; Saltoglu, N. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Healthcare Personnel: A University Hospital Experience. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1343.

- Chew, N.W.S.; Cheong, C.; Kong, G.; Phua, K.; Ngiam, J.N.; Tan, B.Y.Q.; Wang, B.; Hao, F.; Tan, W.; Han, X.; et al. An Asia-Pacific study on healthcare workers’ perceptions of, and willingness to receive, the COVID-19 vaccination. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 106, 52–60.

- Ciardi, F.; Menon, V.; Jensen, J.L.; Shariff, M.A.; Pillai, A.; Venugopal, U.; Kasubhai, M.; Dimitrov, V.; Kanna, B.; Poole, B.D. Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions of COVID-19 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers of an Inner-City Hospital in New York. Vaccines 2021, 9, 516.

- Khubchandani, J.; Macias, Y. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in Hispanics and African-Americans: A review and recommendations for practice. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2021, 15, 100277.

- Momplaisir, F.M.; Kuter, B.J.; Ghadimi, F.; Browne, S.; Nkwihoreze, H.; Feemster, K.A.; Frank, I.; Faig, W.; Shen, A.K.; Offit, P.A.; et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Health Care Workers in 2 Large Academic Hospitals. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2121931.

- Painter, E.M.; Ussery, E.N.; Patel, A.; Hughes, M.M.; Zell, E.R.; Moulia, D.L.; Scharf, L.G.; Lynch, M.; Ritchey, M.D.; Toblin, R.L.; et al. Demographic Characteristics of Persons Vaccinated During the First Month of the COVID-19 Vaccination Program—United States, December 14, 2020–January 14, 2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 174–177.

- Schrading, W.A.; Trent, S.A.; Paxton, J.H.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Swanson, M.B.; Mohr, N.M.; Talan, D.A.; Project, C.E.D.N. Vaccination rates and acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among U.S. emergency department health care personnel. Acad. Emerg. Med. Off. J. Soc. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2021, 28, 455–458.

- Moore, J.X.; Gilbert, K.L.; Lively, K.L.; Laurent, C.; Chawla, R.; Li, C.; Johnson, R.; Petcu, R.; Mehra, M.; Spooner, A.; et al. Correlates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among a Community Sample of African Americans Living in the Southern United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 879.

- Fares, S.; Elmnyer, M.M.; Mohamed, S.S.; Elsayed, R. COVID-19 Vaccination Perception and Attitude among Healthcare Workers in Egypt. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 21501327211013303.

- Manning, M.L.; Gerolamo, A.M.; Marino, M.A.; Hanson-Zalot, M.E.; Pogorzelska-Maziarz, M. COVID-19 vaccination readiness among nurse faculty and student nurses. Nurs. Outlook 2021, 69, 565–573.

- Parente, D.J.; Ojo, A.; Gurley, T.; LeMaster, J.W.; Meyer, M.; Wild, D.M.; Mustafa, R.A. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination Among Health System Personnel. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2021, 34, 498–508.

- Biswas, N.; Mustapha, T.; Khubchandani, J.; Price, J.H. The Nature and Extent of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in Healthcare Workers. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 1244–1251.

- Browne, S.K.; Feemster, K.A.; Shen, A.K.; Green-McKenzie, J.; Momplaisir, F.M.; Faig, W.; Offit, P.A.; Kuter, B.J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine hesitancy among physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses in two academic hospitals in Philadelphia. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021, 1–9.

- Galanis, P.; Vraka, I.; Fragkou, D.; Bilali, A.; Kaitelidou, D. Intention of healthcare workers to accept COVID-19 vaccination and related factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2021, 14, 543–554.

- Qattan, A.M.N.; Alshareef, N.; Alsharqi, O.; Al Rahahleh, N.; Chirwa, G.C.; Al-Hanawi, M.K. Acceptability of a COVID-19 Vaccine Among Healthcare Workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 644300.

- Bell, S.; Clarke, R.M.; Ismail, S.A.; Ojo-Aromokudu, O.; Naqvi, H.; Coghill, Y.; Donovan, H.; Letley, L.; Paterson, P.; Mounier-Jack, S. COVID-19 vaccination beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours among health and social care workers in the UK: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0260949.

- Navin, M.C.; Oberleitner, L.M.-S.; Lucia, V.C.; Ozdych, M.; Afonso, N.; Kennedy, R.H.; Keil, H.; Wu, L.; Mathew, T.A. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Healthcare Personnel Who Generally Accept Vaccines. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 519–529.

- Kirzinger, A.; Kearney, A.; Hamel, L.; Brodie, M. KFF/The Washington Post Frontline Health Care Workers Survey; Kaiser Family Foundation: Oakland, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–26.

- Geller, A.I.; Budnitz, D.S.; Dubendris, H.; Gharpure, R.; Soe, M.; Wu, H.; Kalayil, E.J.; Benin, A.L.; Patel, S.A.; Lindley, M.C.; et al. Surveillance of COVID-19 Vaccination in Nursing Homes, United States, December 2020–July 2021. Public Health Rep. 2022, 137, 239–243.

- Unroe, K.T.; Evans, R.; Weaver, L.; Rusyniak, D.; Blackburn, J. Willingness of Long-Term Care Staff to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine: A Single State Survey. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 593–599.

- Lang, M.A.; Stahlman, S.; Wells, N.Y.; Fedgo, A.A.; Patel, D.M.; Chauhan, A.; Mancuso, J.D. Disparities in COVID-19 vaccine initiation and completion among active component service members and health care personnel, 11 December 2020–12 March 2021. MSMR 2021, 28, 2–9.

- The Chairtis Group. Vaccine Hesitancy Among Rural Hospitals: The Arrival of a Challenging “New Normal”. 2021. Available online: https://www.chartis.com/insights/vaccine-hesitancy-among-rural-hospitals-arrival-challenging-new-normal (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Dubov, A.; Distelberg, B.J.; Abdul-Mutakabbir, J.C.; Beeson, W.L.; Loo, L.K.; Montgomery, S.B.; Oyoyo, U.E.; Patel, P.; Peteet, B.; Shoptaw, S.; et al. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in Southern California: Not Just “Anti” vs. “Pro” Vaccine. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1428.

- El-Sokkary, R.H.; El Seifi, O.S.; Hassan, H.M.; Mortada, E.M.; Hashem, M.K.; Gadelrab, M.R.M.A.; Tash, R.M.E. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Egyptian healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 762.

- Lazer, D.; Qu, H.; Ognyanova, K.; Baum, M.; Perlis, R.H.; Druckman, J.; Uslu, A.; Lin, J.; Santillana, M.; Green, J.; et al. The COVID States Project #40: COVID-19 Vaccine Attitudes among Healthcare Workers. 18 February 2021. Available online: https://osf.io/yhk5j (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Shallal, A.; Abada, E.; Musallam, R.; Fehmi, O.; Kaljee, L.; Fehmi, Z.; Alzouhayli, S.; Ujayli, D.; Dankerlui, D.; Kim, S.; et al. Evaluation of COVID-19 Vaccine Attitudes among Arab American Healthcare Professionals Living in the United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 942.

- Paris, C.; Bénézit, F.; Geslin, M.; Polard, E.; Baldeyrou, M.; Turmel, V.; Tadié, É.; Garlantezec, R.; Tattevin, P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 51, 484–487.

- Kim, M.H.; Son, N.-H.; Park, Y.S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.A.; Kim, Y.C. Effect of a hospital-wide campaign on COVID-19 vaccination uptake among healthcare workers in the context of raised concerns for life-threatening side effects. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258236.

- Cowan, S.K.; Mark, N.; Reich, J.A. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Is the New Terrain for Political Division among Americans. Socius 2021, 7, 23780231211023657.

- Kerr, J.; Panagopoulos, C.; van der Linden, S. Political polarization on COVID-19 pandemic response in the United States. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 179, 110892.

- SOBO, E.J. THEORIZING (VACCINE) REFUSAL: Through the Looking Glass. Cult. Anthropol. 2016, 31, 342–350.

- Gabarron, E.; Oyeyemi, S.O.; Wynn, R. COVID-19-related misinformation on social media: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 455–463A.

- Jennings, W.; Stoker, G.; Bunting, H.; Valgarðsson, V.O.; Gaskell, J.; Devine, D.; McKay, L.; Mills, M.C. Lack of Trust, Conspiracy Beliefs, and Social Media Use Predict COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 593.

- Piltch-Loeb, R.; Savoia, E.; Goldberg, B.; Hughes, B.; Verhey, T.; Kayyem, J.; Miller-Idriss, C.; Testa, M. Examining the effect of information channel on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251095.

- Wilson, S.L.; Wiysonge, C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e004206.

- González Cano-Caballero, M.; Gil García, E.; Garrido Peña, F.; Cano-Caballero Galvez, M.D. Opinions of Andalusian primary health care professionals. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2018, 41, 27–34.

- Pataka, A.; Kotoulas, S.; Stefanidou, E.; Grigoriou, I.; Tzinas, A.; Tsiouprou, I.; Zarogoulidis, P.; Courcoutsakis, N.; Argyropoulou, P. Acceptability of Healthcare Professionals to Get Vaccinated against COVID-19 Two Weeks before Initiation of National Vaccination. Medicina 2021, 57, 611.

- Öncel, S.; Alvur, M.; Çakıcı, Ö. Turkish Healthcare Workers’ Personal and Parental Attitudes to COVID-19 Vaccination From a Role Modeling Perspective. Cureus 2022, 14, e22555.

- Simonson, M.D.; Baum, M.; Lazer, D.; Ognyanova, K.; Gitomer, A.; Perlis, R.H.; Uslu, A.; Druckman, J.; Green, J.; Santillana, M. The COVID States Project# 45: Vaccine Hesitancy And Resistance Among Parents. 2021. Available online: https://osf.io/e95bc/ (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Wileden, L. The Link Betwee Parents’ and Children’s Vaccination in Detroit; The University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2022.

- Ma, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Han, X.; Huang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Feng, L.; Yang, W.; Wang, C. Willingness toward COVID-19 vaccination, coadministration with other vaccines and receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster: A cross-sectional study on the guardians of children in China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1–9.

- Pan, F.; Zhao, H.; Nicholas, S.; Maitland, E.; Liu, R.; Hou, Q. Parents’ Decisions to Vaccinate Children against COVID-19: A Scoping Review. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1476.

- Hudson, A.; Montelpare, W.J. Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy: Implications for COVID-19 Public Health Messaging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8054.

- Raude, J. L’hésitation vaccinale: Une perspective psychosociologique. Bull. L’académie Natl. Médecine 2016, 200, 199–209.

- Khuller, D. Why Are So Many Health-Care Workers Resisting the COVID Vaccine? The New Yorker. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/science/medical-dispatch/why-are-so-many-health-care-workers-resisting-the-covid-vaccine (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Grochowska, M.; Ratajczak, A.; Zdunek, G.; Adamiec, A.; Waszkiewicz, P.; Feleszko, W. A Comparison of the Level of Acceptance and Hesitancy towards the Influenza Vaccine and the Forthcoming COVID-19 Vaccine in the Medical Community. Vaccines 2021, 9, 475.

- Kashif, M.; Fatima, I.; Ahmed, A.M.; Arshad Ali, S.; Memon, R.S.; Afzal, M.; Saeed, U.; Gul, S.; Ahmad, J.; Malik, F.; et al. Perception, Willingness, Barriers, and Hesitancy Towards COVID-19 Vaccine in Pakistan: Comparison Between Healthcare Workers and General Population. Cureus 2021, 13, e19106.

- Wang, M.-W.; Wen, W.; Wang, N.; Zhou, M.-Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; Ni, J.; Jiang, J.-J.; Zhang, X.-W.; Feng, Z.-H.; Cheng, Y.-R. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance Among Healthcare Workers and Non-healthcare Workers in China: A Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 709056.

- Al-Metwali, B.Z.; Al-Jumaili, A.A.; Al-Alag, Z.A.; Sorofman, B. Exploring the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021, 27, 1112–1122.

- Detoc, M.; Bruel, S.; Frappe, P.; Tardy, B.; Botelho-Nevers, E.; Gagneux-Brunon, A. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7002–7006.

- Pan American Health Organization. Policy Brief—Addressing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in the Caribean; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Meyer, M.N.; Gjorgjieva, T.; Rosica, D. Trends in Health Care Worker Intentions to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine and Reasons for Hesitancy. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e215344.

- Pal, S.; Shekhar, R.; Kottewar, S.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Pathak, D.; Kapuria, D.; Barrett, E.; Sheikh, A.B. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Attitude toward Booster Doses among US Healthcare Workers. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1358.

- Woolf, K.; Gogoi, M.; Martin, C.A.; Papineni, P.; Lagrata, S.; Nellums, L.B.; McManus, I.C.; Guyatt, A.L.; Melbourne, C.; Bryant, L.; et al. Healthcare workers’ views on mandatory SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the UK: A cross-sectional, mixed-methods analysis from the UK-REACH study. eClinicalMedicine. 2022, 46, 101346.

- Choi, K.; Chang, J.; Luo, Y.X.; Lewin, B.; Munoz-Plaza, C.; Bronstein, D.; Rondinelli, J.; Bruxvoort, K. “Still on the Fence:” A Mixed Methods Investigation of COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence Among Health Care Providers. Workplace Health Saf. 2022, 70, 21650799211049811.