Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Christian Quintus Scheckhuber | -- | 3137 | 2023-04-26 20:56:15 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 3137 | 2023-04-27 03:38:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Tienda-Vázquez, M.A.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Elizondo-Luévano, J.H.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Lara-Ortiz, J.S.; Luna-Sosa, B.; Scheckhuber, C.Q. Treatment of Bacterial Infections in T2DM Patients. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43540 (accessed on 14 March 2026).

Tienda-Vázquez MA, Melchor-Martínez EM, Elizondo-Luévano JH, Parra-Saldívar R, Lara-Ortiz JS, Luna-Sosa B, et al. Treatment of Bacterial Infections in T2DM Patients. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43540. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Tienda-Vázquez, Mario Adrián, Elda M. Melchor-Martínez, Joel H. Elizondo-Luévano, Roberto Parra-Saldívar, Javier Santiago Lara-Ortiz, Brenda Luna-Sosa, Christian Quintus Scheckhuber. "Treatment of Bacterial Infections in T2DM Patients" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43540 (accessed March 14, 2026).

Tienda-Vázquez, M.A., Melchor-Martínez, E.M., Elizondo-Luévano, J.H., Parra-Saldívar, R., Lara-Ortiz, J.S., Luna-Sosa, B., & Scheckhuber, C.Q. (2023, April 26). Treatment of Bacterial Infections in T2DM Patients. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43540

Tienda-Vázquez, Mario Adrián, et al. "Treatment of Bacterial Infections in T2DM Patients." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 April, 2023.

Copy Citation

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the metabolic disease with the highest morbidity rates worldwide. The condition is characterized by hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and chronic inflammation, among other detrimental conditions. These decrease the efficiency of the immune system, leading to an increase in the susceptibility to bacterial infections. Maintaining an optimal blood glucose level is crucial in relation to the treatment of T2DM, because if the level of this carbohydrate is lowered, the risk of infections can be reduced.

type 2 diabetes mellitus

bacterial infection

hyperglycemia

antidiabetic plants

1. Brief Overview of Strategies to Combat T2DM

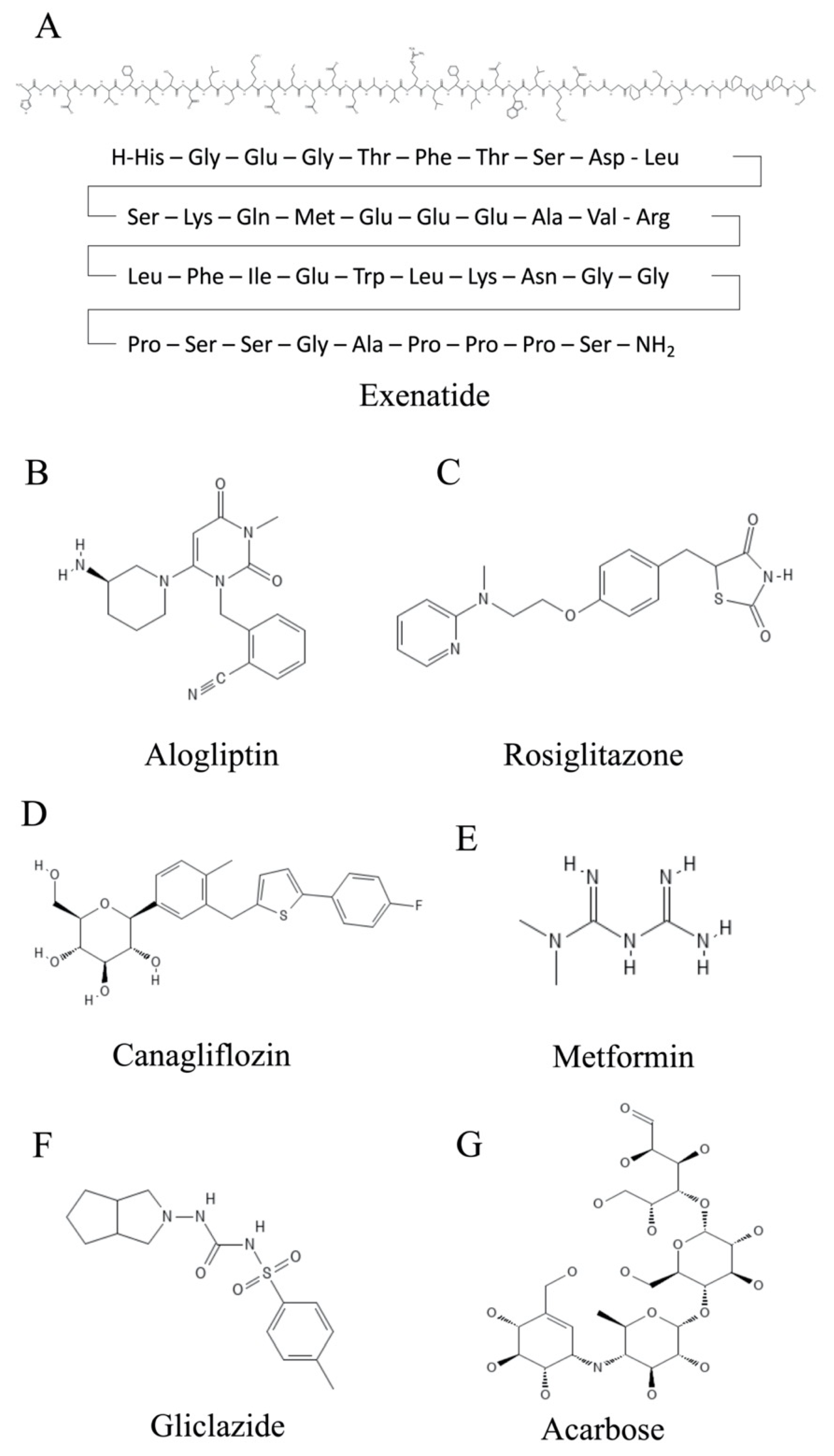

This section gives a short overview of established and commonly prescribed pharmaceuticals for the treatment of T2DM (Figure 1 and Table 1). For a detailed description of compounds for the treatment of T2DM and their modes of action, the reader is referred to several excellent reviews on this topic [1][2][3].

Figure 1. Chemical structures of compounds used for the treatment of T2DM. (A) Exenatide. (B) Alogliptin. (C) Rosiglitazone. (D) Canagliflozin. (E) Metformin. (F) Gliclazide. (G) Acarbose.

One strategy to treat T2DM is to enhance both the production and release of insulin from pancreatic β cells by modulating signaling via the GLP1 (glucagon-like-peptide 1) system [4][5]. GLP1 is a peptide hormone that is formed in the intestine. GLP1 interacts with its receptor, GLPR1 (glucagon-like-peptide receptor 1), which is located on the β cells of the pancreas and on the neurons of the brain. In addition, by increasing insulin levels, the amount of the insulin antagonist glucagon circulating in the blood is decreased. A further effect mediated by GLP1 signaling is reduced food intake [6]. Consequently, agonists of GLP1R are attractive compounds for treating T2DM-associated complications. Among these are drugs such as dulaglutide, exenatide (Figure 1A and Table 1) and liraglutide. Dulaglutide is a recombinant DNA-produced analog of GLP1 (7-37) that is covalently connected to each Fc arm of human IgG [7]. Exenatide has a natural origin, as it was first identified in the saliva of the North American Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), a venomous lizard, although it is now manufactured biotechnologically [8]. A new strategy is the use of dual GIP (glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide)/GLP-1 receptor agonists such as tirzepatide, which has recently been approved by the European Medicines Agency [9]. This approach seems to be promising, as the treatments demonstrate improved efficacy, i.e., better reduction of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and body weight than the exclusive use of GLP-1 analogues such as dulaglutide and semaglutide [10].

GLP1 is subject to degradation by the enzyme dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 (DPP4) [11]. In addition to several other complications, T2DM patients present elevated DPP4 levels. In addition to maintaining higher levels of detrimental glucose, disease phenotypes of hepatocytes are manifested, e.g., fibrosis or even apoptosis [5]. The gliptins are competitive inhibitors of DPP4 and can, therefore, counteract the detrimental action of this proteolytic enzyme. Among these are compounds such as alogliptin (Figure 1B and Table 1) and linagliptin, in addition to a few others [12].

Another way to combat T2DM is to enhance the sensitivity of the body to respond to insulin. Here, thiazolidinedione insulin sensitizers play an important role [13]. Two established members of this family are pioglitazone and rosiglitazone (Figure 1C and Table 1), which are both capable of strongly activating the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) [14]. This receptor has various important roles in the differentiation and function of adipocytes. Ligand binding to PPARγ leads to the stimulation of adipokine production and processing and increases the sensitivity of target cells to insulin, among other functions [15][16]. This process is accompanied by a decrease in free fatty acids in the blood plasma. Both pioglitazone and rosiglitazone have additional mechanisms of action [17]. Pioglitazone has been shown to decrease gluconeogenesis in the liver and reduce the quantity of glucose and glycated hemoglobin in the bloodstream [18]. In addition to its insulin-sensitizing function, rosiglitazone shows anti-inflammatory effects [19]. This is due to an increase in the NF-κB inhibitor (IκB), which targets the molecular signal nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), thereby reducing the inflammatory response.

The Na-dependent glucose transporter SGLT2 is necessary for the reabsorption of glucose in the kidney’s proximal tubule epithelium [20]. As such, it is also an attractive target for pharmacological intervention for the treatment of T2DM. The inhibition of SGLT2 by gliflozins (e.g., canagliflozin (Figure 1D and Table 1) and dapagliflozin) results in the elevated excretion of excess glucose, in addition to reducing both body weight and risks of complications in the cardiovascular system [21][22].

Metformin is one of the oldest pharmacological substances for lowering glucose levels in plasma. It was already described in 1922 [23][24]. The biguanide metformin (Figure 1E and Table 1) has several modes of action that help patients suffering from T2DM and obesity. For example, it inhibits the metabolic pathway of gluconeogenesis in the liver, mostly by inhibiting mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [25][26]. Furthermore, it is proposed to down-regulate the mitochondrial respiratory chain via binding to complex I and to activate the metabolic regulator kinase AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [27]. Although it is the first line of treatment against T2DM and obesity, its exact molecular mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

There are also ways to increase the secretion of insulin by the β cells of the pancreas. The sulfonylureas (e.g., gliclazide (Figure 1F and Table 1)) offer relevant treatment options in this regard [28][29]. They block the potassium channels of the β cells. The subsequent cell depolarization leads to an influx of calcium ions, which elicits exocytosis of insulin-containing vesicles from the β cells. This helps to lower the glucose levels in the blood.

In 1996, the Bayer group introduced acarbose as an intestinal drug. This compound originates from soil bacteria (Actinoplanes utahensis) [30]. Acarbose (C25H43NO18) is a tetrasaccharide-derived metabolite that is constituted by valienamine bonded via nitrogen to isomaltotriose (Figure 1G) [31]. This is a drug used in the treatment of T2DM, and it plays a fundamental role as a mixed non-competitive inhibitor of α-amylase and competitive inhibitor of α-glucosidase in delaying the complete release of glucose for absorption into the bloodstream, meaning glucose will not appear in the digestive system but will appear completely in the distal parts of the intestine [32][33]. Said enzymes participate in the decomposition of carbohydrates or the hydrolysis of oligosaccharides (sucrose and glucose), that is, the inhibitor slows down the metabolism with the aim that the foods consumed with a high sugar content are more slowly assimilated for people with diabetes [34]. In other words, acarbose blocks the ability of the previously mentioned digestive enzymes to break down starch and carbohydrates in the gastrointestinal tract.

Acarbose is one of the most widely used drugs because it is an affordable compound. However, acarbose is not currently the most widely used inhibitor by the medical community due to its gastrointestinal side effects (i.e., flatulence and abdominal discomfort). The doses of its application range from 25 mg to 200 mg, with 100 mg being the average dose of its oral administration three times a day after food ingestion [35].

Lastly, there are further options to pharmacologically target α-glycoside hydrolases in the intestine using iminosugars such as the drug miglitol [36]. Mechanistically, the conjugate acid mimics the positive charge characteristic of the transition state for the enzymatic hydrolysis of the glucoside bond [37]. One route to synthesize iminosugars is via chemical conversion of 1,2-azidoacetates [38]. This approach allows the production of potential antidiabetic drugs such as novel piperidine derivatives [39].

Table 1. Several pharmacological compounds for the treatment of T2DM.

| Compound | Molecular Weight | Description of Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alogliptin | 339.39 g/mol | A highly selective DPP4 inhibitor, it results in the prolonged effect of incretin GLP1 and, thus, increases insulin secretion and inhibits glucagon secretion, helping to lower blood glucose and to achieve improved glycemic control in T2DM patients. | [40] |

| Rosiglitazone | 357.43 g/mol | Through activation of PPARγ, it has primary effects on adipose tissue and decreases insulin resistance by reducing hepatic triglycerides, decreasing visceral fat mass, and increasing subcutaneous fat mass. | [17] |

| Canagliflozin | 444.52 g/mol | As a competitive, reversible, and highly selective SGLT2 inhibitor, it leads to a reduction in glucose reabsorption from primary urine. The induced glucosuria results in optimized glycemic control as well as an energy deficit, which translates into a body weight reduction. | [41] |

| Metformin | 129.16 g/mol | Exact mechanisms remain elusive. It acts as an antihyperglycemic agent, possibly through a decrease in hepatic glucose production partially caused by an interaction with the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I. | [42] |

| Gliclazide | 323.41 g/mol | Belongs to the group of sulfonylureas that stimulate basal and meal-stimulated insulin secretion through binding to the B cell receptor SUR1, a subunit of an ATP sensitive potassium channel, which, when blocked, leads to an increase in insulin secretion. | [43][44] |

| Exenatide | 4186.63 g/mol | A GLP1R agonist, it acts to increase glucose-dependent insulin secretion from B cells, suppress glucagon secretion, and delay gastric emptying, and it leads to a reduction in calorie intake and body weight. | [45][46] |

2. The Treatment of Bacterial Infections in T2DM Patients

Individuals with T2DM are at a higher risk of developing infectious diseases. The main reasons for this are an impaired immune system, a hyperglycemic environment, and other associated factors [47]. In addition, there is a relationship between diabetes and bacterial infections, since bacterial infections such as malignant otitis externa, periodontitis, emphysematous pyelonephritis, and emphysematous cholecystitis are much more frequent in diabetic patients. These can be more serious in diabetics than in non-diabetics [48]. These infections are usually the first manifestation of unrecognized long-standing diabetes [49]. The most common bacteria are streptococci, pneumococci, and enterobacteria, and several reasons can explain this correlation [50][51][52]. In T2DM patients, more glucose is available that can be used by invading bacteria as a source of metabolic energy, which boosts the proliferation rate. Perhaps even more pronounced is the link between a strongly activated and compromised immune system and bacterial infections in T2DM patients [47]. The end products of choline degradation by Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria have been associated with the development of cardiovascular disease and diabetes as products that favor the development of harmful oxidative stress [53].

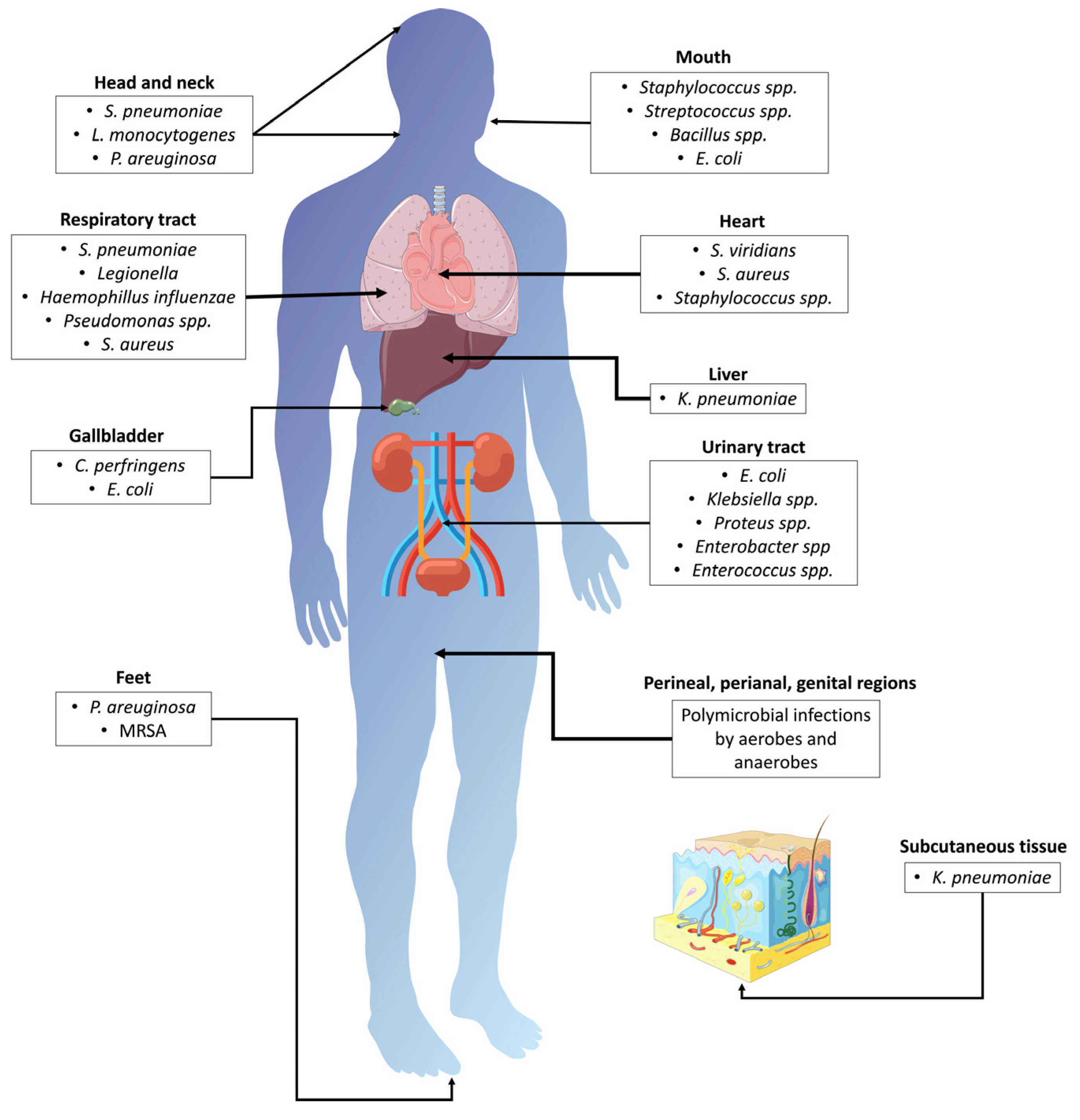

In addition to the medical complications seen in patients suffering from T2DM, an elevated risk of contracting bacterial infections is observed, with Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli being regarded as the most common ones [54]. The most frequent site of infection is the urinary tract (UTIs, urinary tract infections) [55][56][57][58] (Figure 2), leading to acute pyelonephritis and asymptomatic bacteriuria, among other complications. In 2005, Brown et al. identified further risk factors for infections of the urinary tract, such as age and additional conditions (e.g., primarily diabetic cystopathy and nephropathy) [59]. The main risk factors for UTIs in T2DM are inadequate glycemic control, duration of T2DM, diabetic microangiopathy, impaired leukocyte function, recurrent vaginitis, and anatomical and functional abnormalities of the urinary tract [60][61].

Figure 2. Bacterial infections associated with T2DM. MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; S. pneumoniae: Streptococcus pneumoniae; L. monocytogenes: Listeria monocytogenes; E. coli: Escherichia coli; S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus; S. viridians: Streptococcus viridians; K. pneumoniae: Klebsiella pneumoniae; C. perfringens: Clostridium perfringens; P. aeruginosa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Several reasons can explain this correlation. In T2DM patients, there is a clearly documented link between a strongly activated and compromised immune system and bacterial infections in T2DM patients [57][62]. Here, various aspects can be distinguished [63]. First, the rheological attributes of blood cells are significantly altered in many T2DM patients [64]. For example, blood viscosity is increased, leading to a multitude of adverse effects, such as limited oxygen concentrations in the microenvironment of immune cells. Therefore, only a limited defense can be mounted against intruding bacteria, increasing the chance of severe bacterial infections. Another example is the lowered blood pH that is often seen in patients suffering from hyperglycemia [65]. This effect is mainly caused by diabetic ketoacidosis and can result in a decreased blood pH below the physiological value of approximately 7.3. Further biochemical alterations that might favor infections in T2DM patients are an impairment of the pentose phosphate pathway, which is participating in the antioxidant defense by synthesizing the reduction equivalent NADPH [66], and the limited functionality of the Na+/K+ ATPase [67], which regulates a plethora of cellular functions.

Diabetes-associated immunodeficiency is also a predisposing factor for pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae meningitis, which can cause bacterial meningitis, leading to an altered mental status and increased mortality [49]. Cefotaxime/ceftriaxone plus amoxicillin/ampicillin/penicillin G are the standard antibiotics used in these cases [68][69].

Foot infections are a serious and common complication of DM. High blood sugar levels can damage the nerves and blood vessels in the feet, leading to poor circulation and decreased sensation [70]. This can make it difficult to detect injuries, such as cuts or blisters, which can then become infected and potentially lead to more serious complications [70]. In fact, foot infections are one of the most common reasons for hospitalization among people with diabetes [70]. If left untreated, they can lead to serious complications such as osteomyelitis (infection of the bone), gangrene, and even amputation. In severe cases, foot infections can also lead to sepsis (a potentially life-threatening infection that spreads throughout the body) [71]. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis are isolated from around 60% of all infected ulcers. Enterococci, streptococci, and enterobacteria are less frequent, and 15% of infected ulcers contain strictly anaerobic bacteria [71]. Therefore, it is important for people with diabetes to take proper care of their feet, including daily washing and inspection, wearing appropriate footwear, and seeking prompt medical attention for any injuries or signs of infection [70]. This can help prevent foot infections and reduce the risk of serious complications.

The three most serious head and neck infections in diabetic persons are invasive external otitis (IEO), rhinocerebral mucormycosis, and periodontitis [47]. IEO, also known as malignant otitis externa, is a serious infection that can affect the ear canal and skull base. It is most commonly seen in elderly patients with poorly controlled diabetes, although it can also occur in individuals with weakened immune systems or those with chronic ear infections [72]. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis is another serious infection that can affect the head and neck region [73]. It is a rare but life-threatening fungal infection that can affect the sinuses, brain, and other organs. It is a rare, opportunistic and invasive infection caused by fungi of the class Zygomycetes [73]. Periodontitis is more common in persons with T2DM and is considered the sixth most common complication of DM [74]. This condition initiates or disseminates insulin resistance, thus affecting glycemic control. Poor glycemic control has been associated with a greater incidence and progression of gingivitis and periodontitis [75]. This pathogenesis is mainly caused by Porphyromonas gingivalis, which acts as a critical agent by altering host immune homeostasis [76]. Lipopolysaccharides, proteases, fimbriae, and other virulence factors are among the strategies used by P. gingivalis to promote bacterial colonization and facilitate the growth of the surrounding microbial community [76]. These virulence factors modulate various host immune components by evading bacterial clearance or inducing an inflammatory environment [77].

Fournier gangrene is a type of necrotizing fasciitis that affects the male genitalia and surrounding areas. The most common bacteria that cause this condition are E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., and Peptostreptococcus spp. [78]. However, it is not uncommon for the infection to be polymicrobial, involving several different types of bacteria such as Clostridium, aerobic or anaerobic streptococci, and Bacteroides [48]. Approximately 70% of patients with Fournier gangrene have DM, which is a risk factor for developing this condition. The infection typically starts in the scrotum but can extend to involve the penis, perineum, and abdominal wall [56]. It is important to note that despite the severity of the infection, the testicles are usually spared from the disease [48]. Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment are crucial to preventing the spread of the infection and reducing mortality rates. Treatment involves surgical debridement to remove the infected tissue, along with broad-spectrum antibiotics to target the bacterial infection [79]. Patients with Fournier gangrene often require hospitalization and intensive care management [80].

Respiratory tract infections are responsible for many medical appointments by persons with T2DM [60]. The most frequent respiratory infections associated with DM are caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and the influenza virus, and persons with DM also have a high possibility of being infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Table 2 gives an overview of bacterial pathogens that are associated with T2DM.

Some of the drugs described in the previous section have been investigated in terms of whether they have beneficial functions for treating bacterial infections in T2DM patients. Only metformin is reported to have clear effects on reducing the pathophysiology of infectious disease mediated by bacteria [81][82]. In a mouse model, metformin administration reduced infections mediated by bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [83]. Specifically, P. aeruginosa growth is inhibited by metformin in an epithelial cell line of the lungs (Calu-3) [84]. Furthermore, metformin administration also reduces the risk of infections by Mycobacterium tuberculosis [85]. For other commonly used drugs to combat T2DM, either no data are available at the time of writing or they have no effects [63].

Table 2. Associated pathogenesis of bacterial infections in T2DM.

| Disease | Microorganism | Symptoms | Conventional Treatment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck infections | Streptococcus pneumoniae and Listeria monocytogenes Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Bacterial meningitis Malignant otitis externa |

Cefotaxime/ceftriaxone plus amoxicillin/ampicillin/penicillin G. Long-term monotherapy with oral ciprofloxacin. |

[49][86][87] |

| Periodontitis | Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Bacillus spp., E. coli | Inflammation in the periodontal tissues is stimulated by the long-term presence of subgingival biofilm, suppuration from periodontal pockets, and tooth loss | Oral and periodontal health (intensive periodontal treatment) and glycemic control. | [88] |

| Respiratory infections | Streptococcus pneumonia, Legionella spp., Haemophilus influenza, Pseudomonas spp., Staphylococcus aureus |

Community-acquired pneumonia/hospital-acquired pneumonia | Initial outpatient treatment: Combination therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid/cephalosporin and macrolide/doxycycline or monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone. Severe in-patient pneumonia: β lactam + macrolide or β lactam + fluoroquinolone. |

[89][90][91] |

| Infective endocarditis | Streptococcus viridans, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus species | Acute heart failure, stroke, atrioventricular block, septic shock, and cardiogenic shock | Ampicillin with flucloxacillin, oxacillin with gentamicin, or vancomycin with gentamicin and rifampicin. | [92][93] |

| Emphysematous cholecystitis | Clostridium perfringens and E. coli | Biliary tract infection | Surgical removal of the gallbladder and broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy. | [94] |

| Liver | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Pyogenic liver abscess | Combined antibiotic therapy with carbapenems. | [95][96] |

| Urinary tract | E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Enterobacter spp., and Enterococci | Cystitis, pyelonephritis, severe urosepsis, renal abscesses and renal papillary necrosis | Ertapenem, nitrofurantoin, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, cefuroxime, and gentamicin. | [97][98][99] |

| Foot infections in diabetes | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, MRSA | Foot ulcer | β-lactamase inhibitor-amoxicillin/clavulanate; trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; carbapenem; aminoglycoside, colistin, and fluoroquinolone; amputation | [100] |

| Fournier’s gangrene | Polymicrobial infections by aerobes and anaerobes | Necrotizing fasciitis of the perineal, genital, or perianal regions | Broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgical debridement. | [101][102] |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Extensive necrosis of subcutaneous tissue and fascia | Surgery, oxacillin, and a third-generation cephalosporin. | [103] |

MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Compounds from plants can yield valuable results in the treatment of bacterial infections, such as juice extracted from cranberries [104]. It was found that active compounds in this juice are potent inhibitors of bacterial adherence to cells in the urogenital epithelium. The use of plants as a complementary treatment for diabetes and the bacteria that occur in T2DM is supported by several studies. Plants present different bioactive effects, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, bactericidal, and fungicidal activity [105].

References

- Dowarah, J.; Singh, V.P. Anti-Diabetic Drugs Recent Approaches and Advancements. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115263.

- Gloyn, A.L.; Drucker, D.J. Precision Medicine in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Lancet. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 891–900.

- Xie, F.; Chan, J.C.N.; Ma, R.C.W. Precision Medicine in Diabetes Prevention, Classification and Management. J. Diabetes Investig. 2018, 9, 998–1015.

- Gimeno, R.E.; Briere, D.A.; Seeley, R.J. Leveraging the Gut to Treat Metabolic Disease. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 679–698.

- Ferguson, D.; Finck, B.N. Emerging Therapeutic Approaches for the Treatment of NAFLD and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 484–495.

- Chen, X.Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, W.; Xie, A.M. GLP-1 Suppresses Feeding Behaviors and Modulates Neuronal Electrophysiological Properties in Multiple Brain Regions. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 793004.

- Scott, L.J. Dulaglutide: A Review in Type 2 Diabetes. Drugs 2020, 80, 197–208.

- Triplitt, C.; Chiquette, E. Exenatide: From the Gila Monster to the Pharmacy. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2006, 46, 44–55.

- Scheen, A.J. Dual GIP/GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: New Advances for Treating Type-2 Diabetes. Ann. Endocrinol. 2023, 84, 316–321.

- Scheen, A.J.; Radermecker, R.P.; Paquot, N. Focus on tirzepatide, a dual unimolecular GIP-GLP-1 receptor agonist in type 2 diabetes. Rev. Med. Suisse 2022, 18, 1539–1544.

- Ahrén, B. Glucose-Lowering Action through Targeting Islet Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes: Focus on Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibition. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 12, 1128–1135.

- Deacon, C.F. Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 642–653.

- Mastrototaro, L.; Roden, M. Insulin Resistance and Insulin Sensitizing Agents. Metabolism 2021, 125, 154892.

- Wang, S.; Dougherty, E.J.; Danner, R.L. PPARγ Signaling and Emerging Opportunities for Improved Therapeutics. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 111, 76–85.

- Muise, E.S.; Azzolina, B.; Kuo, D.W.; El-Sherbeini, M.; Tan, Y.; Yuan, X.; Mu, J.; Thompson, J.R.; Berger, J.P.; Wong, K.K. Adipose Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Is Up-Regulated by Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma and Altered Metabolic States. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 403–412.

- Astapova, O.; Leff, T. Adiponectin and PPARγ: Cooperative and Interdependent Actions of Two Key Regulators of Metabolism. Vitam. Horm. 2012, 90, 143–162.

- Lebovitz, H.E. Thiazolidinediones: The Forgotten Diabetes Medications. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2019, 19, 151.

- Smith, U. Pioglitazone: Mechanism of Action. Int. J. Clin. Pract. Suppl. 2001, 121, 13–18.

- Siebert, A.; Goren, I.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Frank, S. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Rosiglitazone in Obesity-Impaired Wound Healing Depend on Adipocyte Differentiation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168562.

- Ghezzi, C.; Loo, D.D.F.; Wright, E.M. Physiology of Renal Glucose Handling via SGLT1, SGLT2 and GLUT2. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 2087–2097.

- Tentolouris, A.; Vlachakis, P.; Tzeravini, E.; Eleftheriadou, I.; Tentolouris, N. SGLT2 Inhibitors: A Review of Their Antidiabetic and Cardioprotective Effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2965.

- Cowie, M.R.; Fisher, M. SGLT2 Inhibitors: Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Benefit beyond Glycaemic Control. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 761–772.

- Lamoia, T.E.; Shulman, G.I. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Metformin Action. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 77–96.

- Pernicova, I.; Korbonits, M. Metformin--Mode of Action and Clinical Implications for Diabetes and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 143–156.

- Madiraju, A.K.; Erion, D.M.; Rahimi, Y.; Zhang, X.M.; Braddock, D.T.; Albright, R.A.; Prigaro, B.J.; Wood, J.L.; Bhanot, S.; MacDonald, M.J.; et al. Metformin Suppresses Gluconeogenesis by Inhibiting Mitochondrial Glycerophosphate Dehydrogenase. Nature 2014, 510, 542–546.

- LaMoia, T.E.; Butrico, G.M.; Kalpage, H.A.; Goedeke, L.; Hubbard, B.T.; Vatner, D.F.; Gaspar, R.C.; Zhang, X.M.; Cline, G.W.; Nakahara, K.; et al. Metformin, Phenformin, and Galegine Inhibit Complex IV Activity and Reduce Glycerol-Derived Gluconeogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2122287119.

- Rena, G.; Pearson, E.R.; Sakamoto, K. Molecular Mechanism of Action of Metformin: Old or New Insights? Diabetologia 2013, 56, 1898–1906.

- Lv, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Lu, W. Mechanisms and Characteristics of Sulfonylureas and Glinides. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 37–56.

- Nichols, C.G. Personalized Therapeutics for KATP-Dependent Pathologies. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2022, 63, 541–563.

- Schwientek, P.; Szczepanowski, R.; Rückert, C.; Kalinowski, J.; Klein, A.; Selber, K.; Wehmeier, U.F.; Stoye, J.; Pühler, A. The Complete Genome Sequence of the Acarbose Producer Actinoplanes Sp. SE50/110. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 112.

- Furman, B.L. Acarbose. Ref. Modul. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 2007, 1–3.

- Van de Laar, F.A.; Lucassen, P.L.B.J.; Akkermans, R.P.; Van de Lisdonk, E.H.; Rutten, G.E.H.M.; Van Weel, C. Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitors for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 2009, CD003639.

- Tanoeyadi, S.; Tsunoda, T.; Ito, T.; Philmus, B.; Mahmud, T. Acarbose May Function as a Competitive Exclusion Agent for the Producing Bacteria. ACS Chem. Biol. 2023, 18, 367–376.

- Artasensi, A.; Pedretti, A.; Vistoli, G.; Fumagalli, L. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of Multi-Target Drugs. Molecules 2020, 25, 1987.

- Harrison, D.E.; Strong, R.; Alavez, S.; Astle, C.M.; DiGiovanni, J.; Fernandez, E.; Flurkey, K.; Garratt, M.; Gelfond, J.A.L.; Javors, M.A.; et al. Acarbose Improves Health and Lifespan in Aging HET3 Mice. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12898.

- Gloster, T.M.; Davies, G.J. Glycosidase Inhibition: Assessing Mimicry of the Transition State. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 305–320.

- Tseng, P.-S.; Ande, C.; Moremen, K.W.; Crich, D. Influence of Side Chain Conformation on the Activity of Glycosidase Inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202217809.

- Chennaiah, A.; Bhowmick, S.; Vankar, Y.D. Conversion of Glycals into Vicinal-1{,}2-Diazides and 1,2-(or 2,1)-Azidoacetates Using Hypervalent Iodine Reagents and Me3SiN3. Application in the Synthesis of N-Glycopeptides, Pseudo-Trisaccharides and an Iminosugar. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 41755–41762.

- Sharma, R.; Soman, S.S. Design and Synthesis of Sulfonamide Derivatives of Pyrrolidine and Piperidine as Anti-Diabetic Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 90, 342–350.

- Kaku, K.; Kisanuki, K.; Shibata, M.; Oohira, T. Benefit-Risk Assessment of Alogliptin for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Drug Saf. 2019, 42, 1311–1327.

- Haas, B.; Eckstein, N.; Pfeifer, V.; Mayer, P.; Hass, M.D.S. Efficacy, Safety and Regulatory Status of SGLT2 Inhibitors: Focus on Canagliflozin. Nutr. Diabetes 2014, 4, e143.

- Foretz, M.; Guigas, B.; Viollet, B. Understanding the Glucoregulatory Mechanisms of Metformin in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 569–589.

- Mikov, M.; Đanić, M.; Pavlović, N.; Stanimirov, B.; Goločorbin-Kon, S.; Stankov, K.; Al-Salami, H. Potential Applications of Gliclazide in Treating Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Formulation with Bile Acids and Probiotics. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 43, 269–280.

- Szeto, V.; Chen, N.; Sun, H.; Feng, Z. The Role of KATP Channels in Cerebral Ischemic Stroke and Diabetes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 683–694.

- Nauck, M.A.; Quast, D.R.; Wefers, J.; Meier, J.J. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes—State-of-the-Art. Mol. Metab. 2021, 46, 101102.

- Bridges, A.; Bistas, K.G.; Jacobs, T.F. Exenatide. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022.

- Casqueiro, J.; Casqueiro, J.; Alves, C. Infections in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of Pathogenesis. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16 (Suppl. S1), S27–S36.

- Calvet, H.M.; Yoshikawa, T.T. Infections in Diabetes. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 15, 407–421.

- van Veen, K.E.B.; Brouwer, M.C.; van der Ende, A.; van de Beek, D. Bacterial Meningitis in Diabetes Patients: A Population-Based Prospective Study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36996.

- Thomsen, R.W.; Hundborg, H.H.; Lervang, H.-H.; Johnsen, S.P.; Schønheyder, H.C.; Sørensen, H.T. Risk of Community-Acquired Pneumococcal Bacteremia in Patients with Diabetes: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1143–1147.

- Thomsen, R.W.; Hundborg, H.H.; Lervang, H.-H.; Johnsen, S.P.; Schønheyder, H.C.; Sørensen, H.T. Diabetes Mellitus as a Risk and Prognostic Factor for Community-Acquired Bacteremia Due to Enterobacteria: A 10-Year, Population-Based Study among Adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2005, 40, 628–631.

- Thomsen, R.W.; Riis, A.H.; Kjeldsen, S.; Schønheyder, H.C. Impact of Diabetes and Poor Glycaemic Control on Risk of Bacteraemia with Haemolytic Streptococci Groups A, B, and G. J. Infect. 2011, 63, 8–16.

- Palau-Rodriguez, M.; Tulipani, S.; Isabel Queipo-Ortuño, M.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Tinahones, F.J.; Andres-Lacueva, C. Metabolomic Insights into the Intricate Gut Microbial-Host Interaction in the Development of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1151.

- Ribera, M.C.; Pascual, R.; Orozco, D.; Pérez Barba, C.; Pedrera, V.; Gil, V. Incidence and Risk Factors Associated with Urinary Tract Infection in Diabetic Patients with and without Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2006, 25, 389–393.

- Patterson, J.E.; Andriole, V.T. Bacterial Urinary Tract Infections in Diabetes. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 1997, 11, 735–750.

- Joshi, N.; Caputo, G.M.; Weitekamp, M.R.; Karchmer, A.W. Infections in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1906–1912.

- Shah, B.R.; Hux, J.E. Quantifying the Risk of Infectious Diseases for People with Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 510–513.

- Boyko, E.J.; Fihn, S.D.; Scholes, D.; Abraham, L.; Monsey, B. Risk of Urinary Tract Infection and Asymptomatic Bacteriuria among Diabetic and Nondiabetic Postmenopausal Women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 161, 503–510.

- Brown, J.S.; Wessells, H.; Chancellor, M.B.; Howards, S.S.; Stamm, W.E.; Stapleton, A.E.; Steers, W.D.; Van Den Eeden, S.K.; McVary, K.T. Urologic Complications of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 177–185.

- Peleg, A.Y.; Weerarathna, T.; McCarthy, J.S.; Davis, T.M.E. Common Infections in Diabetes: Pathogenesis, Management and Relationship to Glycaemic Control. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2007, 23, 3–13.

- Chen, S.L.; Jackson, S.L.; Boyko, E.J. Diabetes Mellitus and Urinary Tract Infection: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Proposed Studies in Animal Models. J. Urol. 2009, 182, S51–S56.

- Muller, L.M.A.J.; Gorter, K.J.; Hak, E.; Goudzwaard, W.L.; Schellevis, F.G.; Hoepelman, A.I.M.; Rutten, G.E.H.M. Increased Risk of Common Infections in Patients with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2005, 41, 281–288.

- Chávez-Reyes, J.; Escárcega-González, C.E.; Chavira-Suárez, E.; León-Buitimea, A.; Vázquez-León, P.; Morones-Ramírez, J.R.; Villalón, C.M.; Quintanar-Stephano, A.; Marichal-Cancino, B.A. Susceptibility for Some Infectious Diseases in Patients with Diabetes: The Key Role of Glycemia. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 559595.

- Melkumyants, A.M.; Balashov, S.A. Effect of Blood Viscocity on Arterial Flow Induced Dilator Response. Cardiovasc. Res. 1990, 24, 165–168.

- Umpierrez, G.E.; Kitabchi, A.E. Diabetic Ketoacidosis: Risk Factors and Management Strategies. Treat. Endocrinol. 2003, 2, 95–108.

- Mehta, A.; Mason, P.J.; Vulliamy, T.J. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Baillieres. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2000, 13, 21–38.

- Zadhoush, F.; Sadeghi, M.; Pourfarzam, M. Biochemical Changes in Blood of Type 2 Diabetes with and without Metabolic Syndrome and Their Association with Metabolic Syndrome Components. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2015, 20, 763–770.

- Pomar, V.; de Benito, N.; Mauri, A.; Coll, P.; Gurguí, M.; Domingo, P. Characteristics and Outcome of Spontaneous Bacterial Meningitis in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 292.

- van de Beek, D.; Cabellos, C.; Dzupova, O.; Esposito, S.; Klein, M.; Kloek, A.T.; Leib, S.L.; Mourvillier, B.; Ostergaard, C.; Pagliano, P.; et al. ESCMID Guideline: Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Bacterial Meningitis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22 (Suppl. S3), S37–S62.

- Joseph, W.S.; Lipsky, B.A. Medical Therapy of Diabetic Foot Infections. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2010, 100, 395–400.

- Nicolau, D.P.; Stein, G.E. Therapeutic Options for Diabetic Foot Infections: A Review with an Emphasis on Tissue Penetration Characteristics. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2010, 100, 52–63.

- Carfrae, M.J.; Kesser, B.W. Malignant Otitis Externa. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 41, 537–549.

- Artal, R.; Agreda, B.; Serrano, E.; Alfonso, J.I.; Vallés, H. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: Report on eight cases. Acta Otorrinolaringol. Esp. 2010, 61, 301–305.

- Alves, C.; Andion, J.; Brandão, M.; Menezes, R. Pathogenic aspects of the periodontal disease associated to diabetes mellitus. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2007, 51, 1050–1057.

- Simpson, T.C.; Needleman, I.; Wild, S.H.; Moles, D.R.; Mills, E.J. Treatment of Periodontal Disease for Glycaemic Control in People with Diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 5, CD004714.

- Pussinen, P.J.; Kopra, E.; Pietiäinen, M.; Lehto, M.; Zaric, S.; Paju, S.; Salminen, A. Periodontitis and Cardiometabolic Disorders: The Role of Lipopolysaccharide and Endotoxemia. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 89, 19–40.

- Janket, S.-J.; Javaheri, H.; Ackerson, L.K.; Ayilavarapu, S.; Meurman, J.H. Oral Infections, Metabolic Inflammation, Genetics, and Cardiometabolic Diseases. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 119S–127S.

- Montoya Chinchilla, R.; Izquierdo Morejon, E.; Nicolae Pietricicâ, B.; Pellicer Franco, E.; Aguayo Albasini, J.L.; Miñana López, B. Fournier’s gangrene. Descriptive analysis of 20 cases and literature review. Actas Urol. Esp. 2009, 33, 873–880.

- Tran, H.A.; Hart, A.M. Fournier’s Gangrene. Intern. Med. J. 2006, 36, 200–201.

- Kobayashi, S. Fournier’s Gangrene. Am. J. Surg. 2008, 195, 257–258.

- Mendy, A.; Gopal, R.; Alcorn, J.F.; Forno, E. Reduced Mortality from Lower Respiratory Tract Disease in Adult Diabetic Patients Treated with Metformin. Respirology 2019, 24, 646–651.

- Shih, C.J.; Wu, Y.L.; Chao, P.W.; Kuo, S.C.; Yang, C.Y.; Li, S.Y.; Ou, S.M.; Chen, Y.T. Association between Use of Oral Anti-Diabetic Drugs and the Risk of Sepsis: A Nested Case-Control Study. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15260.

- Garnett, J.P.; Baker, E.H.; Naik, S.; Lindsay, J.A.; Knight, G.M.; Gill, S.; Tregoning, J.S.; Baines, D.L. Metformin Reduces Airway Glucose Permeability and Hyperglycaemia-Induced Staphylococcus Aureus Load Independently of Effects on Blood Glucose. Thorax 2013, 68, 835–845.

- Gill, S.K.; Hui, K.; Farne, H.; Garnett, J.P.; Baines, D.L.; Moore, L.S.P.; Holmes, A.H.; Filloux, A.; Tregoning, J.S. Increased Airway Glucose Increases Airway Bacterial Load in Hyperglycaemia. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27636.

- Pan, S.W.; Yen, Y.F.; Kou, Y.R.; Chuang, P.H.; Su, V.Y.F.; Feng, J.Y.; Chan, Y.J.; Su, W.J. The Risk of TB in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Initiating Metformin vs Sulfonylurea Treatment. Chest 2018, 153, 1347–1357.

- Carlton, D.A.; Perez, E.E.; Smouha, E.E. Malignant External Otitis: The Shifting Treatment Paradigm. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2018, 39, 41–45.

- Yang, T.-H.; Xirasagar, S.; Cheng, Y.-F.; Wu, C.-S.; Kao, Y.-W.; Shia, B.-C.; Lin, H.-C. Malignant Otitis Externa Is Associated with Diabetes: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2020, 129, 585–590.

- Wang, T.-T.; Chen, T.H.-H.; Wang, P.-E.; Lai, H.; Lo, M.-T.; Chen, P.Y.-C.; Chiu, S.Y.-H. A Population-Based Study on the Association between Type 2 Diabetes and Periodontal Disease in 12,123 Middle-Aged Taiwanese (KCIS No. 21). J. Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36, 372–379.

- Akbar, D.H. Bacterial Pneumonia: Comparison between Diabetics and Non-Diabetics. Acta Diabetol. 2001, 38, 77–82.

- Brunetti, V.C.; Ayele, H.T.; Yu, O.H.Y.; Ernst, P.; Filion, K.B. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. CMAJ Open 2021, 9, E62–E70.

- Di Yacovo, S.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Viasus, D.; Adamuz, J.; Oriol, I.; Gili, F.; Vilarrasa, N.; García-Somoza, M.D.; Dorca, J.; Carratalà, J. Clinical Features, Etiology, and Outcomes of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Medicine 2013, 92, 42–50.

- Movahed, M.R.; Hashemzadeh, M.; Jamal, M.M. Increased Prevalence of Infectious Endocarditis in Patients with Type II Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2007, 21, 403–406.

- Abe, T.; Eyituoyo, H.O.; De Allie, G.; Olanipekun, T.; Effoe, V.S.; Olaosebikan, K.; Mather, P. Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Native Valve Infective Endocarditis and Diabetes Mellitus. World J. Cardiol. 2021, 13, 11–20.

- Abengowe, C.U.; McManamon, P.J. Acute Emphysematous Cholecystitis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1974, 111, 1112–1114.

- Thomsen, R.W.; Jepsen, P.; Sørensen, H.T. Diabetes Mellitus and Pyogenic Liver Abscess: Risk and Prognosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2007, 44, 1194–1201.

- Li, W.; Chen, H.; Wu, S.; Peng, J. A Comparison of Pyogenic Liver Abscess in Patients with or without Diabetes: A Retrospective Study of 246 Cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018, 18, 144.

- Mnif, M.F.; Kamoun, M.; Kacem, F.H.; Bouaziz, Z.; Charfi, N.; Mnif, F.; Naceur, B.B.; Rekik, N.; Abid, M. Complicated Urinary Tract Infections Associated with Diabetes Mellitus: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Management. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 17, 442–445.

- Nitzan, O.; Elias, M.; Chazan, B.; Saliba, W. Urinary Tract Infections in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Review of Prevalence, Diagnosis, and Management. Diabetes. Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2015, 8, 129–136.

- Geerlings, S.E.; Meiland, R.; van Lith, E.C.; Brouwer, E.C.; Gaastra, W.; Hoepelman, A.I.M. Adherence of Type 1-Fimbriated Escherichia Coli to Uroepithelial Cells: More in Diabetic Women than in Control Subjects. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1405–1409.

- Nagendra, L.; Boro, H.; Mannar, V. Bacterial Infections in Diabetes. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000.

- Thwaini, A.; Khan, A.; Malik, A.; Cherian, J.; Barua, J.; Shergill, I.; Mammen, K. Fournier’s Gangrene and Its Emergency Management. Postgrad. Med. J. 2006, 82, 516–519.

- Yaghan, R.J.; Al-Jaberi, T.M.; Bani-Hani, I. Fournier’s Gangrene: Changing Face of the Disease. Dis. Colon Rectum 2000, 43, 1300–1308.

- Cheng, N.-C.; Tai, H.-C.; Chang, S.-C.; Chang, C.-H.; Lai, H.-S. Necrotizing Fasciitis in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Mortality. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 417.

- Raz, R.; Chazan, B.; Dan, M. Cranberry Juice and Urinary Tract Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2004, 38, 1413–1419.

- Tienda-Vázquez, M.A.; Morreeuw, Z.P.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Cardador-Martínez, A.; Sabath, E.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Nephroprotective Plants: A Review on the Use in Pre-Renal and Post-Renal Diseases. Plants 2022, 11, 818.

More

Information

Subjects:

Infectious Diseases

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 Apr 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No