Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Md. Shimul Bhuia | -- | 1392 | 2023-04-25 13:56:18 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 1392 | 2023-04-26 10:27:12 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Bhuia, M.S.; Wilairatana, P.; Chowdhury, R.; Rakib, A.I.; Kamli, H.; Shaikh, A.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Islam, M.T. Anticancer Potentials of the Lignan Magnolin. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43458 (accessed on 13 January 2026).

Bhuia MS, Wilairatana P, Chowdhury R, Rakib AI, Kamli H, Shaikh A, et al. Anticancer Potentials of the Lignan Magnolin. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43458. Accessed January 13, 2026.

Bhuia, Md. Shimul, Polrat Wilairatana, Raihan Chowdhury, Asraful Islam Rakib, Hossam Kamli, Ahmad Shaikh, Henrique D. M. Coutinho, Muhammad Torequl Islam. "Anticancer Potentials of the Lignan Magnolin" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43458 (accessed January 13, 2026).

Bhuia, M.S., Wilairatana, P., Chowdhury, R., Rakib, A.I., Kamli, H., Shaikh, A., Coutinho, H.D.M., & Islam, M.T. (2023, April 25). Anticancer Potentials of the Lignan Magnolin. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43458

Bhuia, Md. Shimul, et al. "Anticancer Potentials of the Lignan Magnolin." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 April, 2023.

Copy Citation

Magnolin is a compound found in many different plants. It has been demonstrated to have anticancer activity in numerous experimental models by inhibiting the cell cycle (G1 and G2/M phase); inducing apoptosis; and causing antiinvasion, antimetastasis, and antiproliferative effects via the modulation of several pathways.

lignan

magnolin

biological sources

pharmacokinetic profile

cancer cell lines

1. Introduction

Natural remedies are becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide as conventional or supplementary treatments for curable and incurable diseases and for encouraging health and disease prevention [1]. Due to their negligible side effects and good safety records, they are widely used in various diseases as effective therapeutic routes [2]. Lead compounds are abundant in plants and are used in drug discovery. Most (60–70%) of the antibacterial and anticancer medications used in clinical settings are natural compounds or their derivatives [3][4].

Naturally occurring lignans are a group of secondary metabolites that are found in a variety of sources, such as seeds, nuts, cereals, vegetables, and fruits. Lignans serve a range of purposes in plants, and their multifaceted functions are significant for various organisms, including humans [5][6][7]. They are mainly liable for the defense mechanism and are distinguished by the presence of two terminal phenyl groups in their chemical structure [8]. Phytochemicals that belong to the lignan class exhibit diverse biological features, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiestrogenic, anticarcinogenic, and antitumor activities [9][10]. Several epidemiological studies have suggested that lignans may lower the risk of cardiovascular disease. However, the impact of lignans on other chronic ailments, such as breast cancer, is still debated [11]. Additionally, the dietary intake of lignans has been linked with a diminished risk of other types of cancer, including colon cancer, gastric adenocarcinoma, and esophageal carcinoma. However, there have been very few human studies conducted on this topic [12]. The scientific community has previously mentioned the discovery and development of lignan derivatives for the creation of anticancer therapeutics. Examples of such drugs include etoposide, teniposide, and etopophos [13].

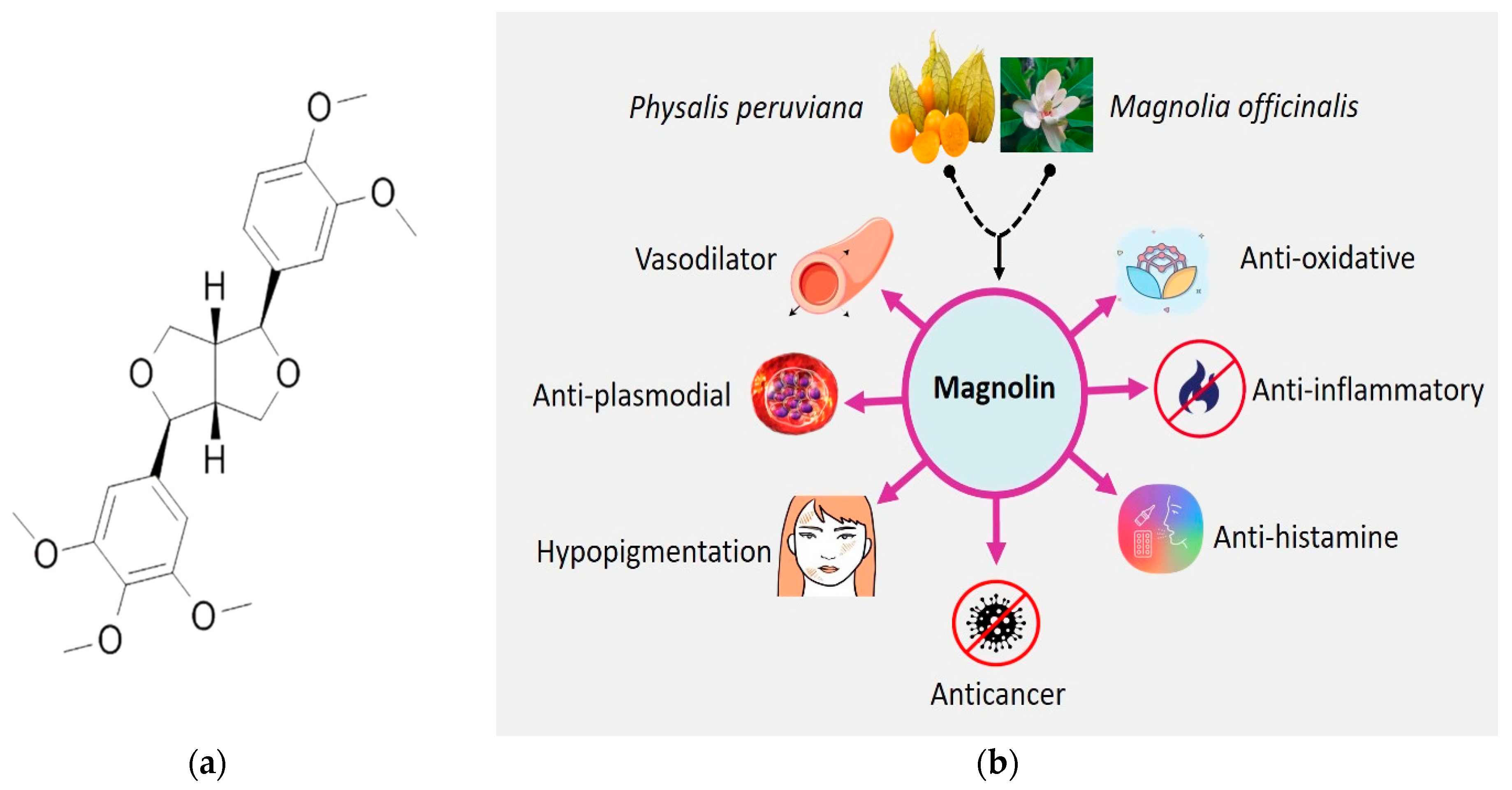

Magnolin is a lignan (C23H28O7, Figure 1), chemically known as (3S,3aR,6S,6aR)-3-(3,4-dimethoxy phenyl)-6-(3,4,5-tri methoxyphenyl)-1,3,3a,4,6,6a-hexahydrofuro[3,4-c] furan, that has been isolated from the Magnolia genus [14][15], which is a large genus of about 210 flowering species in the family Magnoliaceae [16], and has been shown to have health-enhancing properties in in vivo and in vitro test systems [17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. Magnolin exhibits various pharmacological activities, including anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, and vasodilatory effects. It has also been found to have protective effects against contrast-induced nephropathy and has been shown to inhibit the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells [21][23]. Additionally, magnolin has been found to be capable of suppressing cell proliferation and transformation by suppressing the ERKs/RSK2 signaling pathways and impairing the G1/S cell-cycle transition [25].

Figure 1. (a) Two-dimensional chemical structure of magnolin and (b) different pharmacological activities of magnolin based on literature.

2. Botanical Sources

Medicinal plants are considered significant resources for discovering novel drugs worldwide [26][27]. They hold cultural and economic importance to local communities and have been utilized in traditional and popular medicine as well as in the development of pharmaceuticals [28][29]. The commercial and scientific interest in medicinal plants as a source of primary materials for the herbal pharmaceutical industries is increasing rapidly due to the growing global demand [30]. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that a significant proportion of individuals in developing countries (70–95%) rely on medicinal plants for their primary healthcare needs. However, despite their widespread use, only a small fraction (15%) of medicinal plants worldwide has been analyzed to measure their potential therapeutic benefits based on their phytochemical and phytopharmacological properties [31]. Magnolin, a biologically active compound, has been extracted from plants of the Magnolia genus [15]. Three species of magnolia, including Magnolia denudata, Magnolia sprengeri, and Magnolia biondii, have been recognized in the pharmacopoeia and are known for their therapeutic benefits [22]. The compound source is a component of the flowers, leaves, seeds, roots, and aerial portions of numerous species, according to accounts in the literature. The botanical origins of this lignan are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Biological sources of magnolin.

| Plant Name | Plant Part | References |

|---|---|---|

| Magnolia fargesii | Flower buds | [17][32] |

| Zanthoxylum simulans | Bark | [33] |

| M. biondii | Flower buds | [34][35][36] |

| Pseuderanthemum carruthersii | Root | [37] |

| M. officinalis | Flower buds | [38] |

| M. sargentiana and M. sprengeri | - | [22] |

| Castilleja tenuiflora | Aerial part of roots | [39] |

| Astrantia major | Fruits | [40] |

| Artemisia gorgonum Webb | Leaves and flowers | [24] |

| Acorus calamus | - | [41] |

| Rollinia mucosa | Seeds | [42] |

| M. denudata | Flowers | [43][44] |

| M. kobus | Flower buds, bark | [45][46] |

| M. salicifolia | Flower buds | [45] |

| Licaria armeniaca | Trunk wood, fruits | [47][48] |

| Achillea holosericea. | Aerial parts | [49] |

| Annona pickelii | Leaves | [50] |

| M. liliflora | Leaves | [51] |

| A. gypsicola | Aerial parts and roots | [52][53] |

| Z. alatum | Seeds | [54] |

| Hernandia ovigera | Leaves | [55] |

| Physalis peruviana | Fruits | [56] |

3. Cellular and Molecular Anticancer Mechanisms of Magnolin

New precision medicine treatments for cancer are developed by utilizing information obtained from changes that occur at the molecular level in cancer genes and their associated signaling pathways. These days, it is widely acknowledged that signaling pathways and molecular networks play crucial roles in carrying out and regulating vital cellular processes that promote cell survival and growth and are hence largely responsible for the development of cancer as well as its potential treatment [57]. In cancer, two pathways, namely, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signal transduction pathway and the Ras/MEK pathway, are commonly activated or mutated [58]. These pathways are closely interlinked in transmitting signals from receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) to intracellular effector proteins and cell cycle regulators, thus regulating upstream cellular signals [59]. Some other important signaling pathways that develop cancer and can be the target of therapeutic development include cell cycle, Hippo signaling [60], Notch signaling [61], Myc signaling [62][63], oxidative stress response/Nrf2 [64][65], TGFb signaling [66], β-catenin/Wnt signaling [67], and p53 signaling pathways [68]. CDK4/6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) have made significant advancements in cancer treatment among all the signaling pathways targeting CDK4/6 activation [69].

Due to the growing number of deaths caused by cancer, it is essential to develop therapeutic strategies that have fewer cytotoxic side effects and are less prone to resistance. Natural compounds have been found to possess multiple beneficial activities, such as promoting overall health and providing cancer treatment [70]. Natural products have demonstrated preferential advantages against cancer cells when compared to normal cells. Additionally, their chemical structures can serve as models for the development of innovative drugs [70][71]. Using these models, drugs can be formulated that offer comparable or superior benefits to those provided by natural products. Moreover, these drugs may have fewer side effects and lower chances of resistance compared to the original natural products [72][73].

According to various studies in the documented literature on magnolin’s anticancer action, this therapeutic substance may prevent cancer by inhibiting the cell cycle, preventing metastasis, inducing apoptosis, and suppressing cell proliferation and migration [74] (Figure 2). The effective dose and the mechanism of action may differ depending on the kind of cancer (Table 2). Furthermore, the following provides comprehensive information on magnolin’s anticancer mechanism (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Anticancer mechanisms of magnolin.

Table 2. Pharmacological mechanisms of magnolin involved in its anticancer activities.

| Type of Cancer | Experimental Model/ Cell Line |

Tested Concentrations |

Efficacy, IC50 (Exposure Time) |

Anticancer Effects and Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | MDA-MB-231 | 20 and 50 µM | 30.34 µM (24 h) | ↓MEK1/2, ↓ERK1/2, ↓CDK1, ↓BCL2, ↓MMP 2 and 9, ↑CASPASES3 and 9 ↓proliferation, ↓invasion, ↑apoptosis |

[75] |

| MDA-MB-231 | 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µM | - | ↓mRNA expression, ↓PTHrP, ↓MMP9, ↓cathepsin K, ↑RANKL/OPG ratio ↓bone loss and bone-resorbing activity |

[76] | |

| - | MCF-7 | 100 µg/mL | - | ↑cytotoxicity | [37] |

| Lung cancer | JB6CL41, NCI-H1975 and A549 | 15, 30, and 60 µM | - | ↓ERK1/2, ↓MMP2, ↓MMP9, ↓RSK2, ↓migration, ↓invasion | [77] |

| NIH3T3, A549 | 15, 30, and 60 µM | - | ↓ERK1, ↓ERK2, ↓RSK2, ↓ATF1, ↓AP1, ↓proliferation, ↓migration | [78] | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | BEL-7402 and SK-HEP1 | 25, 50, 75 100, and 125 μM | - | ↓MEK, ↓PI3K, ↓AKT, ↓proliferation |

[79] |

| Ovarian cancer | TOV-112D | 15, 30, and 60 µM | - | ↓ERK1, ↓ERK2, ↑P16Ink4a, ↑P27Kip1, ↓G1 and G2/M phase, ↓proliferation | [25] |

| TOV-112D | - | 16 nM 68 nM | ↓ERK1, ↓ERK2, ↓ATF1, ↓RSK2 ↓proliferation |

[80] | |

| Prostate cancer | PANC-1 | - | 0.51 µM | ↓MMP3, ↓proliferation, ↓migration | [56] |

| PC3 and DU145 | 50 and 100 µM | - | ↓AKT, ↓BCL2, ↑BAX, ↑CASPASE3, ↑P53, ↑P21 ↓G1, G2 phase, ↑apoptosis |

[23] | |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | MIA-PaCa | - | - | ↑cytotoxicity | [81] |

| Colon cancer | HCT116 and HT29 | - | - | ↓G2/M-phases, ↓proliferation | [82] |

| Colorectal cancer | HCT116 and SW480 | 10, 20, 30, and 40 µM | - | ↓LIF, ↓STAT3, ↓MCL1 ↑ autophagy ↓cell cycle |

[83] |

Arrows (↑ and ↓) show an increase or decrease in the obtained variables. MEK1/2: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 and 2; ERK1/2: extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2; CDK1: cyclin-dependent kinase 1; BCL2: B-cell lymphoma 2; MMP 2 and 9: matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9; RSK2: ribosomal S6 kinase 2; ATF1: activating transcription factor 1; AP1: activator protein 1; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; AKT: protein kinase B; BAX: Bcl-2-associated X protein; LIF: leukemia inhibitory factor; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; MCL1: myeloid leukemia 1; P53: tumor protein P53; P21: tumor protein P21.

References

- Zhang, A.; Sun, H.; Wang, X. Recent advances in natural products from plants for treatment of liver diseases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 63, 570–577.

- Sasidharan, S.; Chen, Y.; Saravanan, D.; Sundram, K.; Latha, L.Y. Extraction, isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds from plants’ extracts. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 8, 1–10.

- Ebob, O.T.; Babiaka, S.B.; Ntie-Kang, F. Natural products as potential lead compounds for drug discovery against SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2021, 11, 611–628.

- Sikder, L.; Khan, M.R.; Smrity, S.Z.; Islam, M.T.; Khan, S.A. Phytochemical and pharmacological investigation of the ethanol extract of Byttneria pilosa Roxb. Clin. Phytosci. 2022, 8, 1–8.

- Teponno, R.B.; Kusari, S.; Spiteller, M. Recent advances in research on lignans and neolignans. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 1044–1092.

- Ražná, K.; Nôžková, J.; Vargaová, A.; Harenčár, Ľ.; Bjelková, M. Biological functions of lignans in plants. Agriculture 2021, 67, 155–165.

- Magoulas, G.E.; Papaioannou, D. Bioinspired syntheses of dimeric hydroxycinnamic acids (lignans) and hybrids, using phenol oxidative coupling as key reaction, and medicinal significance thereof. Molecules 2014, 19, 19769–19835.

- Kalinová, J.P.; Marešová, I.; Tříska, J.; Vrchotová, N. Distribution of lignans in Panicum miliaceum, Fagopyrum esculentum, Fagopyrum tataricum, and Amaranthus hypochondriacus. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 106, 104283.

- Ionkova, I. Anticancer lignans-from discovery to biotechnology. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 843–856.

- Durazzo, A.; Zaccaria, M.; Polito, A.; Maiani, G.; Carcea, M. Lignan content in cereals, buckwheat and derived foods. Foods 2013, 2, 53–63.

- Peterson, J.; Dwyer, J.; Adlercreutz, H.; Scalbert, A.; Jacques, P.; McCullough, M.L. Dietary lignans: Physiology and potential for cardiovascular disease risk reduction. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 571–603.

- Rodríguez-García, C.; Sánchez-Quesada, C.; Toledo, E.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Gaforio, J.J. Naturally lignan-rich foods: A dietary tool for health promotion? Molecules 2019, 24, 917.

- Su, G.-Y.; Wang, K.-W.; Wang, X.-Y.; Wu, B. Bioactive lignans from Zanthoxylum planispinum with cytotoxic potential. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 11, 120–126.

- Miyazawa, M.; Kasahara, H.; Kameoka, H. Phenolic lignans from flower buds of Magnolia fargesii. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 3666–3668.

- Pan, J.-X.; Hensens, O.D.; Zink, D.L.; Chang, M.N.; Hwang, S.-B. Lignans with platelet activating factor antagonist activity from Magnolia biondii. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 1377–1379.

- Lee, Y.D. Use of Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) Seeds in Medicine, and Possible Mechanisms of Action. In Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 727–732.

- Kim, J.Y.; Lim, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.D.; Jeon, R.; Ryu, J.-H. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of lignans isolated from Magnolia fargesii. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 937–940.

- Ibarra-Alvarado, C.; Rojas, A.; Mendoza, S.; Bah, M.; Gutiérrez, D.; Hernández-Sandoval, L.; Martínez, M. Vasoactive and antioxidant activities of plants used in Mexican traditional medicine for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Pharm. Biol. 2010, 48, 732–739.

- Wang, F.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Gui, D.; Li, J.; Xing, T.; Wang, N. Magnolin protects against contrast-induced nephropathy in rats via antioxidation and antiapoptosis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 203458.

- Uto, T.; Tung, N.H.; Ohta, T.; Shoyama, Y. (+)-Magnolin enhances melanogenesis in melanoma cells and three-dimensional human skin equivalent; involvement of PKA and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Planta Med. 2022, 88, 1199–1208.

- Ma, P.; Che, D.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; An, H.; Zhang, T.; He, H. Magnolin inhibits IgE/Ag-induced allergy in vivo and in vitro. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 76, 105867.

- Shen, Y.; Pang, E.C.; Xue, C.C.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, J.; Li, C.G. Inhibitions of mast cell-derived histamine release by different Flos Magnoliae species in rat peritoneal mast cells. Phytomedicine 2008, 15, 808–814.

- Huang, Y.; Zou, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, J.; Chen, M. Magnolin inhibits prostate cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 87, 714–720.

- Ortet, R.; Prado, S.; Regalado, E.L.; Valeriote, F.A.; Media, J.; Mendiola, J.; Thomas, O.P. Furfuran lignans and a flavone from Artemisia gorgonum Webb and their in vitro activity against Plasmodium falciparum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 138, 637–640.

- Song, J.H.; Lee, C.J.; An, H.J.; Yoo, S.M.; Kang, H.C.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, K.D.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, H.S.; Cho, Y.Y. Magnolin targeting of ERK1/2 inhibits cell proliferation and colony growth by induction of cellular senescence in ovarian cancer cells. Mol. Carcinog. 2019, 58, 88–101.

- Chen, S.-L.; Yu, H.; Luo, H.-M.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.-F.; Steinmetz, A. Conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants: Problems, progress, and prospects. Chin. Med. 2016, 11, 37.

- Nalawade, S.M.; Sagare, A.P.; Lee, C.-Y.; Kao, C.-L.; Tsay, H.-S. Studies on tissue culture of Chinese medicinal plant resources in Taiwan and their sustainable utilization. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 2003, 44, 79–98.

- Kaky, E.; Gilbert, F. Using species distribution models to assess the importance of Egypt’s protected areas for the conservation of medicinal plants. J. Arid Environ. 2016, 135, 140–146.

- Jamshidi-Kia, F.; Lorigooini, Z.; Amini-Khoei, H. Medicinal plants: Past history and future perspective. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 2017, 7, 1–7.

- Bieski, I.G.C.; Leonti, M.; Arnason, J.T.; Ferrier, J.; Rapinski, M.; Violante, I.M.P.; Balogun, S.O.; Pereira, J.F.C.A.; Figueiredo, R.d.C.F.; Lopes, C.R.A.S. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants by population of valley of Juruena region, legal Amazon, Mato Grosso, Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 383–423.

- De Luca, V.; Salim, V.; Atsumi, S.M.; Yu, F. Mining the biodiversity of plants: A revolution in the making. Science 2012, 336, 1658–1661.

- Chen, C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Hsu, H. On the Ca++-Antagonistic Principles of the Flower Buds of Magnolia fargesii1. Planta Med. 1988, 54, 438–440.

- Peng, C.-Y.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Deng, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.-H.; Zhou, X.-J. Lignans from the bark of Zanthoxylum simulans. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 17, 232–238.

- Feng, T.; Zheng, L.; Liu, F.; Xu, X.; Mao, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yu, X. Growth factor progranulin promotes tumorigenesis of cervical cancer via PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 58381.

- Zhao, W.; Zhou, T.; Fan, G.; Chai, Y.; Wu, Y. Isolation and purification of lignans from Magnolia biondii Pamp by isocratic reversed-phase two-dimensional liquid chromatography following microwave-assisted extraction. J. Sep. Sci. 2007, 30, 2370–2381.

- Ma, Y.; Han, G. Biologically active lignins from Magnolia biondii Pamp. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 1995, 20, 102–104.

- Vo, T.N.; Nguyen, P.L.; Tuong, L.T.; Pratt, L.M.; Vo, P.N.; Nguyen, K.P.P.; Nguyen, N.S. Lignans and triterpenes from the root of Pseuderanthemum carruthersii var. atropurpureum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 60, 1125–1133.

- Hong, P.T.L.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, W.K.; Nam, J.H. Flos magnoliae constituent fargesin has an anti-allergic effect via ORAI1 channel inhibition. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Off. J. Korean Physiol. Soc. Korean Soc. Pharmacol. 2021, 25, 251–258.

- Arango-De la Pava, L.D.; Zamilpa, A.; Trejo-Espino, J.L.; Domínguez-Mendoza, B.E.; Jiménez-Ferrer, E.; Pérez-Martínez, L.; Trejo-Tapia, G. Synergism and subadditivity of verbascoside-lignans and-iridoids binary mixtures isolated from castilleja tenuiflora benth. on NF-κB/AP-1 inhibition activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 547.

- Radulović, N.S.; Mladenović, M.Z.; Ðorđević, N.D. Chemotypification of Astrantia major L. (Apiaceae): Essential-Oil and Lignan Profiles of Fruits. Chem. Biodivers. 2012, 9, 1320–1337.

- Qiao, D.; Gan, L.-S.; Mo, J.-X.; Zhou, C.-X. Chemical constituents of Acorus calamus. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2012, 37, 3430–3433.

- Chávez, D.; Acevedo, L.A.; Mata, R. Tryptamine derived amides and acetogenins from the seeds of Rollinia mucosa. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1119–1122.

- Jo, Y.-H.; Seo, G.-U.; Yuk, H.-G.; Lee, S.-C. Antioxidant and tyrosinase inhibitory activities of methanol extracts from Magnolia denudata and Magnolia denudata var. purpurascens flowers. Food Res. Int. 2012, 47, 197–200.

- Seo, Y. Antioxidant activity of the chemical constituents from the flower buds of Magnolia denudata. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2010, 15, 400–406.

- Li, J.; Tanaka, M.; Kurasawa, K.; Ikeda, T.; Nohara, T. Studies of the chemical constituents of the flower buds of Magnolia kobus and M. salicifolia. J. Nat. Med. 2007, 61, 222–223.

- Lee, H.J.; Seo, S.M.; Lee, O.K.; Jo, H.J.; Kang, H.Y.; Choi, D.H.; Paik, K.H.; Khan, M. Lignans from the bark of Magnolia kobus. Helv. Chim. Acta 2008, 91, 2361–2366.

- Alegrio, L.V.; Fo, R.B.; Gottlieb, O.R.; Maia, J.G.S. Lignans and neolignans from Licaria armeniaca. Phytochemistry 1981, 20, 1963–1965.

- Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Yoshida, M.; Gottlieb, O.R. Neolignans from the fruits of Licaria armeniaca. Phytochemistry 1986, 26, 319–321.

- Ahmed, A.A.; Mahmoud, A.A.; Ali, E.T.; Tzakou, O.; Couladis, M.; Mabry, T.J.; Gáti, T.; Tóth, G. Two highly oxygenated eudesmanes and 10 lignans from Achillea holosericea. Phytochemistry 2002, 59, 851–856.

- Dutra, L.M.; Costa, E.V.; de Souza Moraes, V.R.; de Lima Nogueira, P.C.; Vendramin, M.E.; Barison, A.; do Nascimento Prata, A.P. Chemical constituents from the leaves of Annona pickelii (Annonaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2012, 41, 115–118.

- Wu, H.-B.; Liu, T.-T.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Wang, W.-S.; Zhu, W.-W.; Li, L.-F.; Li, Y.-R.; Chen, X. Leaves of Magnolia liliflora Desr. as a high-potential by-product: Lignans composition, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-phytopathogenic fungal and phytotoxic activities. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 125, 416–424.

- Trifunović, S.; Vajs, V.; Tešević, V.; Djoković, D.; Milosavljević, S. Lignans from the plant species Achillea lingulata. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2003, 68, 277–280.

- Öksüz, S.; Ulubelen, A.; Tuzlaci, E. Constituents of Achillea teretifolia. Fitoterapia 1990, 61, 283.

- Jain, N.; Srivastava, S.; Aggarwal, K.; Ramesh, S.; Kumar, S. Essential oil composition of Zanthoxylum alatum seeds from northern India. Flavour Fragr. J. 2001, 16, 408–410.

- Nishino, C.; Mitsui, T. Lignans from Hernandia Ovigera linn. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973, 14, 335–338.

- Sayed, A.M.; El-Hawary, S.S.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Ghareeb, M.A. Antiproliferative potential of Physalis peruviana-derived magnolin against pancreatic cancer: A comprehensive in vitro and in silico study. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 11733–11743.

- Yip, H.Y.K.; Papa, A. Signaling pathways in cancer: Therapeutic targets, combinatorial treatments, and new developments. Cells 2021, 10, 659.

- Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 789–799.

- Pons-Tostivint, E.; Thibault, B.; Guillermet-Guibert, J. Targeting PI3K signaling in combination cancer therapy. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 454–469.

- Pan, D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 491–505.

- Callahan, R.; Egan, S.E. Notch signaling in mammary development and oncogenesis. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2004, 9, 145–163.

- Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Olopade, O.I. MYC and breast cancer. Genes Cancer 2010, 1, 629–640.

- Zaytseva, O.; Kim, N.-H.; Quinn, L.M. MYC in brain development and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7742.

- Schmidlin, C.J.; Shakya, A.; Dodson, M.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. The intricacies of NRF2 regulation in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 76, 110–119.

- LeBoeuf, S.E.; Wu, W.L.; Karakousi, T.R.; Karadal, B.; Jackson, S.R.; Davidson, S.M.; Wong, K.-K.; Koralov, S.B.; Sayin, V.I.; Papagiannakopoulos, T. Activation of oxidative stress response in cancer generates a druggable dependency on exogenous non-essential amino acids. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 339–350.e4.

- Fabregat, I.; Fernando, J.; Mainez, J.; Sancho, P. TGF-beta signaling in cancer treatment. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 2934–2947.

- Sanchez-Vega, F.; Mina, M.; Armenia, J.; Chatila, W.K.; Luna, A.; La, K.C.; Dimitriadoy, S.; Liu, D.L.; Kantheti, H.S.; Saghafinia, S. Oncogenic signaling pathways in the cancer genome atlas. Cell 2018, 173, 321–337.

- Sui, X.; Jin, L.; Huang, X.; Geng, S.; He, C.; Hu, X. p53 signaling and autophagy in cancer: A revolutionary strategy could be developed for cancer treatment. Autophagy 2011, 7, 565–571.

- Rader, J.; Russell, M.R.; Hart, L.S.; Nakazawa, M.S.; Belcastro, L.T.; Martinez, D.; Li, Y.; Carpenter, E.L.; Attiyeh, E.F.; Diskin, S.J. Dual CDK4/CDK6 Inhibition Induces Cell-Cycle Arrest and Senescence in NeuroblastomaCDK4/6 Inhibition in Neuroblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 6173–6182.

- Hashem, S.; Ali, T.A.; Akhtar, S.; Nisar, S.; Sageena, G.; Ali, S.; Al-Mannai, S.; Therachiyil, L.; Mir, R.; Elfaki, I. Targeting cancer signaling pathways by natural products: Exploring promising anti-cancer agents. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 113054.

- Shah, U.; Shah, R.; Acharya, S.; Acharya, N. Novel anticancer agents from plant sources. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2013, 11, 16–23.

- Darnell, J.E., Jr. STATs and gene regulation. Science 1997, 277, 1630–1635.

- Cragg, G.M.; Grothaus, P.G.; Newman, D.J. Impact of natural products on developing new anti-cancer agents. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3012–3043.

- Patel, D.K. Therapeutic Effectiveness of Magnolin on cancers and other Human complications. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2022, 6, 100203.

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, K.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Q. Magnolin inhibits proliferation and invasion of breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells by targeting the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 421–427.

- Jun, A.Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Park, K.-K.; Son, K.H.; Lee, D.H.; Woo, M.-H.; Chung, W.-Y. Tetrahydrofurofuran-type lignans inhibit breast cancer-mediated bone destruction by blocking the vicious cycle between cancer cells, osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Investig. New Drugs 2014, 32, 1–13.

- Lee, C.-J.; Lee, M.-H.; Yoo, S.-M.; Choi, K.-I.; Song, J.-H.; Jang, J.-H.; Oh, S.-R.; Ryu, H.-W.; Lee, H.-S.; Surh, Y.-J. Magnolin inhibits cell migration and invasion by targeting the ERKs/RSK2 signaling pathway. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 576.

- Lee, C.-J.; Lee, H.S.; Ryu, H.W.; Lee, M.-H.; Lee, J.Y.; Li, Y.; Dong, Z.; Lee, H.-K.; Oh, S.-R.; Cho, Y.-Y. Targeting of magnolin on ERKs inhibits Ras/ERKs/RSK2-signaling-mediated neoplastic cell transformation. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 432–441.

- Wang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, X.; Meng, L.; Song, C.; Yu, C.; Jiang, N.; Liu, Y. Synergistic activity of magnolin combined with B-RAF inhibitor SB590885 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via targeting PI3K-AKT/mTOR and ERK MAPK pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 3816.

- Yoo, S.-M.; Lee, C.-J.; Kim, S.-M.; Cho, S.-Y.; Park, J.; Cho, Y.-Y. Molecular mechanisms of magnolin resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 4028.

- Mukhija, M.; Dhar, K.L.; Kalia, A.N. Bioactive Lignans from Zanthoxylum alatum Roxb. stem bark with cytotoxic potential. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 152, 106–112.

- Park, J.; Lee, G.E.; An, H.J.; Lee, C.J.; Cho, E.S.; Kang, H.C.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, D.J.; et al. Kaempferol sensitizes cell proliferation inhibition in oxaliplatin-resistant colon cancer cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2021, 44, 1091–1108.

- Yu, H.; Yin, S.; Zhou, S.; Shao, Y.; Sun, J.; Pang, X.; Han, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Jin, C.; et al. Magnolin promotes autophagy and cell cycle arrest via blocking LIF/Stat3/Mcl-1 axis in human colorectal cancers. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 702.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

835

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

26 Apr 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No