Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Péter Mauchart | -- | 1658 | 2023-04-21 11:37:05 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1658 | 2023-04-23 09:38:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Mauchart, P.; Vass, R.A.; Nagy, B.; Sulyok, E.; Bódis, J.; Kovács, K. Oxidative Stress on the Reproductive Tract of Males. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43315 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Mauchart P, Vass RA, Nagy B, Sulyok E, Bódis J, Kovács K. Oxidative Stress on the Reproductive Tract of Males. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43315. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Mauchart, Péter, Réka Anna Vass, Bernadett Nagy, Endre Sulyok, József Bódis, Kálmán Kovács. "Oxidative Stress on the Reproductive Tract of Males" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43315 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Mauchart, P., Vass, R.A., Nagy, B., Sulyok, E., Bódis, J., & Kovács, K. (2023, April 21). Oxidative Stress on the Reproductive Tract of Males. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43315

Mauchart, Péter, et al. "Oxidative Stress on the Reproductive Tract of Males." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 April, 2023.

Copy Citation

The reduction of molecular oxygen (O2) yields superoxide (•O2−), which is the precursor of most other reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS originate from the mitochondria along with other superoxides, and have a complex role in numerous cell signaling pathways that control cell proliferation rates and other cellular activities, such as molecular responses to hypoxia.

IVF

antioxidants

light protection

embryo

1. Introduction

In the past few decades, the study of the role of oxidative stress (OS) in reproductive health has become more and more popular. Oxygen is a key element of aerobic life, and oxidative metabolism represents an essential supply of energy. All multicellular aerobic organisms require molecular oxygen for their survival. The electron configuration of oxygen is special, as it has two unpaired electrons in different orbits in its outer shell, which makes it prone to forming radicals. The reduction of molecular oxygen (O2) yields superoxide (•O2−), which is the precursor of most other reactive oxygen species (ROS) [1][2]. ROS originate from the mitochondria along with other superoxides, and have a complex role in numerous cell signaling pathways that control cell proliferation rates and other cellular activities, such as molecular responses to hypoxia [3][4][5].

Moreover, ROS have a significant effect on the oxidative modification of many macromolecules such as proteins, receptors, ion channels, or transcription factors [6][7]. Consequently, a small amount of ROS are essential for the natural cell functions [8]. There are two types of oxidants that can produce free radicals: endogenous and exogenous oxidants. ROS are highly reactive and thus unstable, but they can be stabilized by acquiring electrons from nearby molecules (e.g., lipids, proteins, nucleic acids), resulting in cell damage and pathology [9][10][11]. Therefore, OS can cause lipid peroxidation and DNA and protein damage. In a healthy environment, every aerobic cell has a defense system against ROS, there is a precisely adjusted balance (homeostasis) between prooxidants and antioxidants (AOX). Superoxide anions (O2−), hydroxyl radicals (OH−), peroxyls (ROO), alkoxyls (RO), and hydroperoxyls (HO2) have the biggest biological importance among ROS. Enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants are the two types of antioxidants that can be found in the body under normal conditions. The most prominent enzymatic antioxidants are catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), glutathione reductase (GSH-R), and superoxide dismutase (SOD), which can cause the reduction of hydrogen-peroxide (H2O2) to alcohol and water.

2. Effect of Oxidative Stress on the Reproductive Tract of Males

2.1. Sources of ROS in Sperm

Spermatozoa obtain energy from two major metabolic pathways: glycolysis, which occurs in the main part of the flagellum, and oxidative phosphorylation, which occurs in mitochondria located in the flagellum’s midpiece [12]. There is no evidence that the process of the tricarboxylic acid cycle plays a role in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. By obtaining approximately 30 molecules of ATP by oxidizing one molecule of glucose, oxidative phosphorylation is the more efficient pathway. During glycolysis only two molecules of ATP are gained from each molecule of glucose.

2.2. Physiological Role of ROS in Sperm

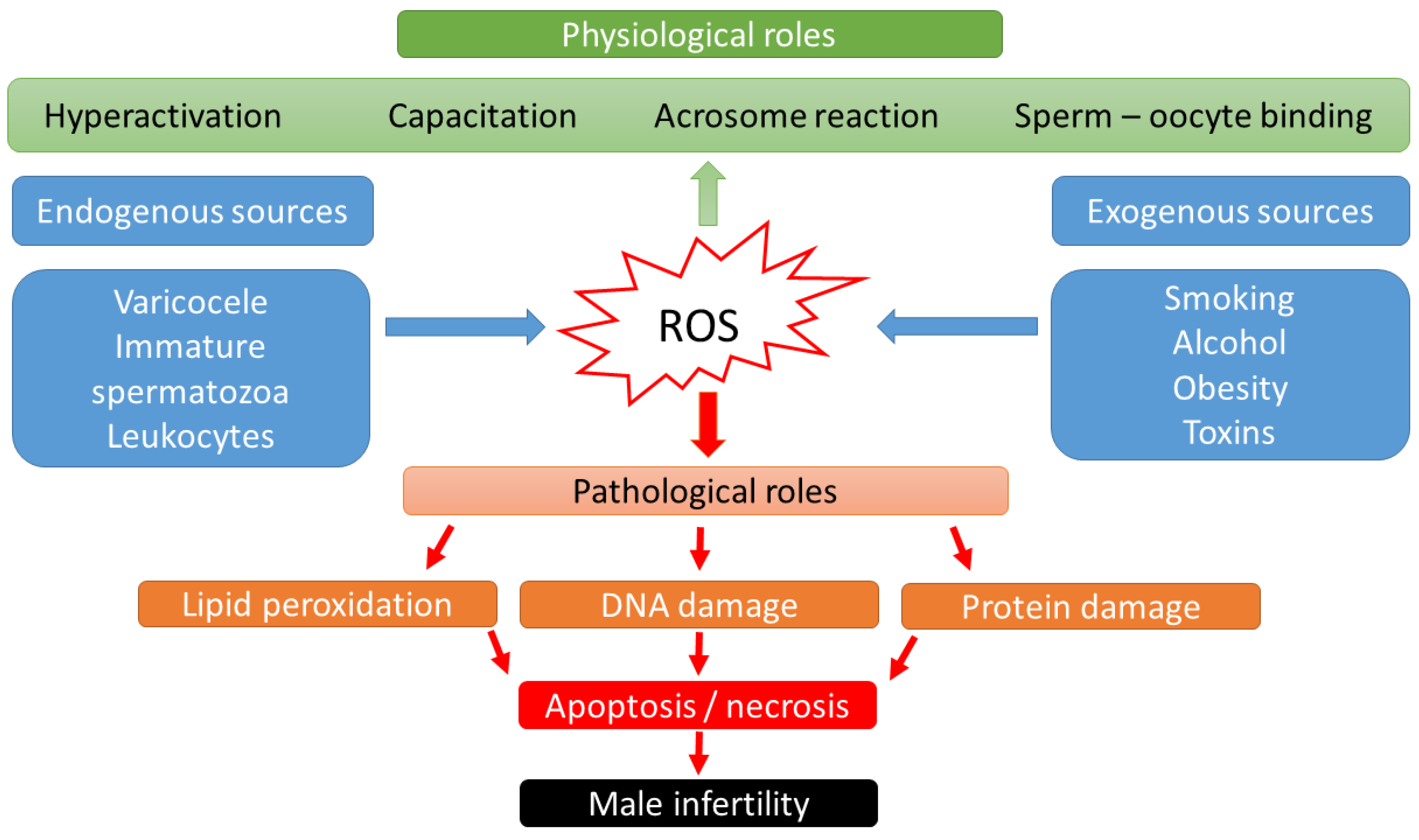

Over the last two decades, it has become known that ROS may have a dual role in sperm function [13]: low ROS levels promote numerous intracellular processes leading to oocyte fertilization, whereas higher ROS levels may lead to DNA damage and embryo loss [14][15] (Figure 1). Physiological levels of ROS have an impact on diverse signaling pathways that regulate physiological redox-sensitive activities, since ROS generally mediates cell proliferation, apoptotic pathways that regulate the cell cycle and programmed cell death [16]. In order to fertilize the oocyte, spermatozoa must undergo various processes in the epididymis, such as sperm maturation, and in the female reproductive tract after ejaculation, such as hyperactivation, capacitation, and the acrosome reaction. During sperm maturation, ROS levels in seminal fluid have been shown to be critical for membrane protein rearrangements, enzymatic modulations, and nuclear remodeling [17]. In the case of nuclear remodeling, in addition to the inevitable replacement of histone proteins with smaller protamines [18], ROS also play a non-negligible role in stabilizing disulfide bonds to maintain chromatin stability [17]. During the ROS-mediated process of hyperactivation, the motility pattern of sperm changes significantly [19]. The hyperactivated sperm is characterized by a high-amplitude, asymmetric beating pattern of the sperm tail (flagellum). The biochemical background was recently described by Dutta et al., 2020 [20]: Calcium ions (Ca2+) and ROS (superoxide, O2−) mediate activation of adenylate cyclase (AC) and increased production of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which activates protein kinase A (PKA) [21]. Increased levels of PKA lead to activation of protein tyrosine kinase (PTK), resulting in phosphorylation of serine (Ser) and tyrosine (Tyr) residues. These steps lead to the essential changes in the cytoskeleton of the flagellum and the fibrous sheath of the axoneme. In parallel with hyperactivation, the increased level of phosphorylated tyrosine residues (P-Tyr) also leads to the process of capacitation, when the sperm cell prepares for the acrosome reaction. The biochemical features of the acrosome reaction overlap with those of capacitation. Both processes involve the influx of Ca2+ and increased levels of cAMP, PKA, and PKC. However, molecules such as phospholipase A2 (PLA2) are also involved in the acrosome reaction. PLA2 is activated in spermatozoa by progesterone secreted from the cumulus cell and cleaves intact phosphoglycerolipids into free fatty acids and lysophospholipids, increasing the fluidity of the sperm plasma membrane in preparation for sperm–oocyte fusion [22]. Then, the capacitated sperm binds to a glycoprotein of the zona pellucida, the process of which leads to oocyte penetration, and sperm head decondensation [22][23]. ROS have a low-level role as a second messenger in these fertilization processes.

Figure 1. Scheme of physiological and pathological effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) on male fertility.

2.3. Pathological Role of ROS in Sperm

High levels of ROS biological markers were identified in semen samples from 25–40% of infertile men [24]. Thus, male sub- and infertility are frequently related to OS. The source of the OS could be categorized into endogenous and exogenous factors. Lifestyle habits, such as alcohol intake, smoking, contact with toxic materials (radiation or environmental pollutants), or pathological abnormalities such as obesity, varicocele, stress, and aging have been connected with elevated production of adipokines, cytokines, and high levels of ROS in seminal plasma [25]. Supraphysiologic ROS levels have been correlated with the presence of leukocytes in seminal fluid, as well as a high percentage of morphologically abnormal spermatozoa [26] or immature spermatozoa with cytoplasmatic droplets containing a high number of enzymes [22][27]. In cases of leukocytospermia (no. of leukocytes ≥ 1 × 106/mL), an increase in extracellular ROS generation is particularly evident, as the antioxidant protection of the seminal plasma becomes insufficient. Activated leukocytes can produce 100 times more ROS than non-activated leukocytes during inflammation or infection [28].

In the context of ART, gametes are exposed to in vitro modification, which regularly exposes these cells to OS [29]. However, leukocytes can be removed from sperm suspensions using procedures such as density gradient centrifugation (DGC) or swim-up; however, using these techniques without serum albumin has been related to sperm damage in several studies. In the absence of albumin, free radicals created by mitochondria during centrifugation trigger membrane lipid peroxidation and DNA damage [30][31]. This damage could be caused by peroxide produced by manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) from superoxide radicals in tightly packed sperm pellets. It is released from damaged mitochondria and causes lipid peroxidation of the cell membrane, depolarization of mitochondria, decreased ATP synthesis, and sperm motility [32][33]. Advanced selection approaches such as microelectrophoresis, Zeta potential, and microfluidic technologies could be used to reduce the induction of OS and the resulting increase in DNA damage. However, such technologies are still used infrequently in clinics [34].

2.4. Effects of OS on Sperm Functions

Lipid peroxidation of the sperm membrane is the major mechanism of ROS-induced sperm destruction, which leads to infertility. Because their cell membrane and cytoplasm contain large quantities of polyunsaturated fatty acids, spermatozoa are sensitive to ROS [35]. This lipid peroxidation reduces sperm motility, likely due to a rapid loss of intracellular ATP, leading to a reduction in axonemal protein phosphorylation, which might result in decrease in motility and, subsequently, sperm immobility [36].

Furthermore, ROS may decrease sperm viability and enhance morphological defects in the mid-piece [37]. In case of DNA damage, the production of basis-free sites, deletions, frameshifts, DNA cross-links, chromosomal rearrangements, and DNA strand breaks could occur [38][39][40]. One study revealed that a 25% increase in ROS level in seminal plasma led to a 10% increase in DNA fragmentation [41]. These changes can cause the start or stop of gene transcription, accelerated degradation of telomeric DNA, epigenetic changes, replication mistakes, and GC-to-TA transversions [42]. In the case of the spermatozoa, only one base excision repair (BER) enzyme has been described, which is the 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 (OGG1). Therefore, the DNA repair potential of spermatozoa is strongly limited, and much more exposed to ROS than other gametes [43]. However, cells normally rely on a variety of intrinsic and extrinsic antioxidant systems to neutralize high amounts of ROS. Enzymatic antioxidants such as SOD, catalase, and thiol peroxidases, as well as nonenzymatic antioxidants such as glutathione, are forms of endogenous antioxidants. Extrinsic antioxidants, on the other hand, are micronutrients such as vitamin C, vitamin E, L-carnitine, N-acetyl cysteine, and trace elements such as selenium or zinc [2] that must be provided from external sources in order to maintain a balance between oxidation and reduction (antioxidation) in any living cell of the body [1].

2.5. Methods Used to Counteract OS Effects

Although there are some contradictory reports that oral consumption of antioxidant-rich medication seems to improve sperm functional parameters such as motility and concentration, as well as decrease DNA damage, there is insufficient evidence that antioxidant consumption has a significant effect on the improving of fertility rates and live birth rates [44]. Furthermore, it is dependent on the type of antioxidants, the duration of treatment, and even the diagnosis of the man’s fertility, among further aspects [44]. A recent study discovered a significant effect of three-month lifestyle changes combined with oral antioxidant intake on DNA fragmentation index (DFI), but no effect on sperm concentration or total motile sperm count [45]. ‘Reductive stress’ refers to a change in the redox levels of the body to a more reduced state. According to reports, reductive stress is just as harmful as oxidative stress [46].

References

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84.

- Zarbakhsh, S. Effect of antioxidants on preimplantation embryo development in vitro: A review. Zygote 2021, 29, 179–193.

- Bell, E.L.; Emerling, B.M.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial regulation of oxygen sensing. Mitochondrion 2005, 5, 322–332.

- Bell, E.L.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial oxygen sensing: Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor by mitochondrial generated reactive oxygen species. Essays Biochem. 2007, 43, 17–28.

- Van Blerkom, J. Mitochondria as regulatory forces in oocytes, preimplantation embryos and stem cells. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2008, 16, 553–569.

- De Giusti, V.C.; Caldiz, C.I.; Ennis, I.L.; Pérez, N.G.; Cingolani, H.E.; Aiello, E.A. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) as signaling molecules of intracellular pathways triggered by the cardiac renin-angiotensin II-aldosterone system (RAAS). Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 126.

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, Q.; Sun, J.; Zhiqiang, E.; Gao, Q. Supplementation of kaempferol to in vitro maturation medium regulates oxidative stress and enhances subsequent embryonic development in vitro. Zygote 2020, 28, 59–64.

- Scialò, F.; Fernández-Ayala, D.J.; Sanz, A. Role of Mitochondrial Reverse Electron Transport in ROS Signaling: Potential Roles in Health and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 428.

- Attaran, M.; Pasqualotto, E.; Falcone, T.; Goldberg, J.M.; Miller, K.F.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R. The effect of follicular fluid reactive oxygen species on the outcome of in vitro fertilization. Int. J. Fertil. Women’s Med. 2000, 45, 314–320.

- Szczepańska, M.; Koźlik, J.; Skrzypczak, J.; Mikołajczyk, M. Oxidative stress may be a piece in the endometriosis puzzle. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 79, 1288–1293.

- Van Langendonckt, A.; Casanas-Roux, F.; Donnez, J. Oxidative stress and peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 77, 861–870.

- Du Plessis, S.S.; Agarwal, A.; Mohanty, G.; van der Linde, M. Oxidative phosphorylation versus glycolysis: What fuel do spermatozoa use? Asian J. Androl. 2015, 17, 230–235.

- Takeshima, T.; Usui, K.; Mori, K.; Asai, T.; Yasuda, K.; Kuroda, S.; Yumura, Y. Oxidative stress and male infertility. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2020, 20, 41–52.

- Carrell, D.T.; Liu, L.; Peterson, C.M.; Jones, K.P.; Hatasaka, H.H.; Erickson, L.; Campbell, B. Sperm DNA fragmentation is increased in couples with unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. Arch. Androl. 2003, 49, 49–55.

- Lewis, S.E.M.; Aitken, R.J. DNA damage to spermatozoa has impacts on fertilization and pregnancy. Cell Tissue Res. 2005, 322, 33–41.

- Khan, A.U.; Wilson, T. Reactive oxygen species as cellular messengers. Chem. Biol. 1995, 2, 437–445.

- Thompson, A.; Agarwal, A.; du Plessis, S.S. Physiological Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Sperm Function: A Review. In Antioxidants in Male Infertility: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers; Parekatil, S.J., Agarwal, A., Eds.; Springer Science+Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 69–89.

- Du Plessis, S.S.; Agarwal, A.; Halabi, J.; Tvrda, E. Contemporary evidence on the physiological role of reactive oxygen species in human sperm function. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2015, 32, 509–520.

- Griveau, J.F.; Le Lannou, D. Reactive oxygen species and human spermatozoa: Physiology and pathology. Int. J. Androl. 1997, 20, 61–69.

- Dutta, S.; Henkel, R.; Sengupta, P.; Agarwal, A. Physiological role of ROS in sperm function. In Male Infertility: Contemporary Clinical Approaches, Andrology, ART and Antioxidants; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 337–345.

- Evans, E.P.P.; Scholten, J.T.M.; Mzyk, A.; Reyes-San-Martin, C.; Llumbet, A.E.; Hamoh, T.; Arts, E.G.J.M.; Schirhagl, R.; Cantineau, A.E. Male subfertility and oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2021, 46, 102071.

- Durairajanayagam, D. Physiological Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Male Reproduction. In Oxidants, Antioxidants and Impact of the Oxidative Status in Male Reproduction; Henkel, R., Samanta, L., Agarwal, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Chapter 1.8; pp. 65–78.

- de Lamirande, E. Reactive oxygen species and sperm physiology. Rev. Reprod. 1997, 2, 48–54.

- Makker, K.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R. Oxidative stress & male infertility. Indian J. Med. Res. 2009, 129, 357–367.

- Kumar, N.; Singh, A.K. Reactive oxygen species in seminal plasma as a cause of male infertility. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 47, 565–572.

- Cooper, T.G. The epididymis, cytoplasmic droplets and male fertility. Asian J. Androl. 2010, 13, 130–138.

- Aziz, N.; Saleh, R.A.; Sharma, R.K.; Lewis-Jones, I.; Esfandiari, N.; Thomas, A.J., Jr.; Agarwal, A. Novel association between sperm reactive oxygen species production, sperm morphological defects, and the sperm deformity index. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 81, 349–354.

- Plante, M.; de Lamirande, E.; Gagnon, C. Reactive oxygen species released by activated neutrophils, but not by deficient spermatozoa, are sufficient to affect normal sperm motility. Fertil. Steril. 1994, 62, 387–393.

- Agarwal, A.; Rosas, I.M.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; Cannarella, R.; Boitrelle, F.; Munoz, L.V.; Finelli, R.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Henkel, R.; Saleh, R. Oxidative Stress and Assisted Reproduction: A Comprehensive Review of Its Pathophysiological Role and Strategies for Optimizing Embryo Culture Environment. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 477.

- Aitken, R.J.; Finnie, J.M.; Muscio, L.; Whiting, S.; Connaughton, H.S.; Kuczera, L.; Rothkirch, T.B.; De Iuliis, G.N. Potential importance of transition metals in the induction of DNA damage by sperm preparation medium. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 2136–2147.

- Muratori, M.; Tarozzi, N.; Carpentiero, F.; Danti, S.; Perrone, F.M.; Cambi, M.; Casini, A.; Azzari, C.; Boni, L.; Maggi, M.; et al. Sperm selection with density gradient centrifugation and swim up: Effect on DNA fragmentation in viable spermatozoa. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7492.

- Barbonetti, A.; Castellini, C.; Di Giammarco, N.; Santilli, G.; Francavilla, S.; Francavilla, F. In vitro exposure of human spermatozoa to bisphenol A induces pro-oxidative/apoptotic mitochondrial dysfunction. Reprod. Toxicol. 2016, 66, 61–67.

- Kotwicka, M.; Skibinska, I.; Jendraszak, M.; Jedrzejczak, P. 17beta-estradiol modifies human spermatozoa mitochondrial function in vitro. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2016, 14, 50.

- Gualtieri, R.; Kalthur, G.; Barbato, V.; Longobardi, S.; Di Rella, F.; Adiga, S.K.; Talevi, R. Sperm Oxidative Stress during In Vitro Manipulation and Its Effects on Sperm Function and Embryo Development. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1025.

- Alvarez, J.G.; Storey, B.T. Differential incorporation of fatty acids into and peroxidative loss of fatty acids from phospholipids of human spermatozoa. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1995, 42, 334–346.

- Agarwal, A.; Saleh, R.A.; Bedaiwy, M.A. Role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of human reproduction. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 79, 829–843.

- De Lamirande, E.; Gagnon, C. Reactive oxygen species and human spermatozoa. I. Effects on the motility of intact spermatozoa and on sperm axonemes. J. Androl. 1992, 13, 368–378.

- Twigg, J.P.; Irvine, D.S.; Aitken, R.J. Oxidative damage to DNA in human spermatozoa does not preclude pronucleus formation at intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 13, 1864–1871.

- Kemal Duru, N.; Morshedi, M.; Oehninger, S. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on DNA and plasma membrane integrity of human spermatozoa. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 74, 1200–1207.

- Aitken, R.; Krausz, C. Oxidative stress, DNA damage and the Y chromosome. Reproduction 2001, 122, 497–506.

- Mahfouz, R.; Sharma, R.; Thiyagarajan, A.; Kale, V.; Gupta, S.; Sabanegh, E.; Agarwal, A. Semen characteristics and sperm DNA fragmentation in infertile men with low and high levels of seminal reactive oxygen species. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 2141–2146.

- Bauer, N.C.; Corbett, A.H.; Doetsch, P.W. The current state of eukaryotic DNA base damage and repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 10083–10101.

- Smith, T.B.; Dun, M.D.; Smith, N.D.; Curry, B.J.; Connaughton, H.S.; Aitken, R.J. The presence of a truncated base excision repair pathway in human spermatozoa, Mediated by OGG1. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 1488–1497.

- Martin-Hidalgo, D.; Bragado, M.J.; Batista, A.R.; Oliveira, P.F.; Alves, M.G. Antioxidants and Male Fertility: From Molecular Studies to Clinical Evidence. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 89.

- Humaidan, P.; Haahr, T.; Povlsen, B.B.; Kofod, L.; Laursen, R.J.; Alsbjerg, B.; Elbaek, H.O.; Esteves, S.C. The combined effect of lifestyle intervention and antioxidant therapy on sperm DNA fragmentation and seminal oxidative stress in IVF patients: A pilot study. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2022, 48, 131–156.

- Panner Selvam, M.K.; Agarwal, A.; Henkel, R.; Finelli, R.; Robert, K.A.; Iovine, C.; Baskaran, S. The effect of oxidative and reductive stress on semen parameters and functions of physiologically normal human spermatozoa. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 152, 375–385.

More

Information

Subjects:

Reproductive Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

951

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

23 Apr 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No