Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tasneem Rangwala* | -- | 2311 | 2023-04-19 10:53:28 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -1 word(s) | 2310 | 2023-04-20 03:07:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Rangwala, T.; Mukheibir, P.; Fane, S. IWCM in Australia. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43229 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Rangwala T, Mukheibir P, Fane S. IWCM in Australia. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43229. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Rangwala, Tasneem, Pierre Mukheibir, Simon Fane. "IWCM in Australia" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43229 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Rangwala, T., Mukheibir, P., & Fane, S. (2023, April 19). IWCM in Australia. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43229

Rangwala, Tasneem, et al. "IWCM in Australia." Encyclopedia. Web. 19 April, 2023.

Copy Citation

Interpretations of integrated water cycle management (IWCM) differ across jurisdictions. IWCM has been explored at global, national, state and regional levels. The concept of IWCM has many interpretations.

integrated water cycle management

integrated water resource management

urban water planning

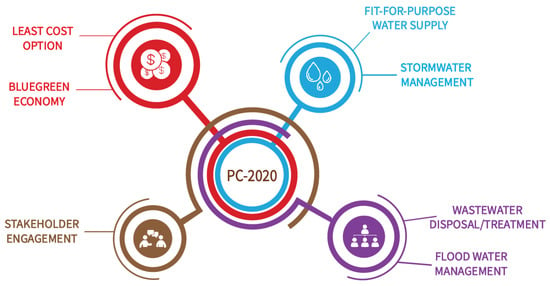

1. IWCM: PC-2020—Productivity Commission, Australia

The Productivity Commission in Australia is a strong promoter of the IWCM concept in the context of water pricing and charges. In 2020, an independent report was commissioned to investigate the implementation of IWCM in Australia. In this report [1], IWCM is defined as a tool to achieve water security via addressing the key functions of urban water management: supplying fit-for-purpose water; wastewater management (appropriate disposal/treatment); stakeholder engagement and involvement; storm and flood water management; and the least-cost option for the provision of services for a blue–green economy.

The PC’s emphasis is on community-based outcomes that include urban amenities, water supply, wastewater management and the consideration of stormwater management as an integral part of water management. Commissioner Doolan has raised the question of why a ‘good idea’ such as an IWCM concept is difficult to implement [2]. The Environment Commissioner for Greater Sydney, Rod Simpson, refers to IWCM as a key driver for urban water planning. The PC’s IWCM concept per the six STEEPI categories focuses mainly on four of the six categories: Water CI, governance, social inclusion and finance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. IWCM by PC, Australia.

Technology and natural resources management are assumed to be fundamental considerations of sustainable management practices and outcomes, without specific reference to their management. It is important to note that the organisational aims and objectives are to achieve a competitive pricing structure, which is well covered in the four STEEPI categories of IWCM.

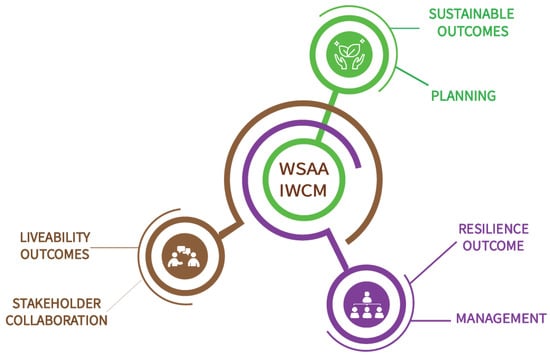

2. WSAA-IWCM—Water Services Association Australia, Australia

WSAA is an industry body providing urban water services in Australia. The organisational context here concerns influencing, promoting, improving and fostering within and between urban water and sustainability in water services. The aims and objectives of WSAA are collaboration and support, which removes the need for the organisation to become involved in its member organisations’ procurement and management of funds and infrastructure and technological needs. Resulting from this, WSAA recently published a document specifically defining the role of IWCM. It categorises IWCM into three major components: (1) management targeting sustainability outcomes, (2) planning targeting liveability outcomes and (3) stakeholder collaboration targeting resilience outcomes [3]. These categories are aligned with three of the six STEEPI categories: (1) NRM, (2) governance and (3) social inclusion, as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. IWCM by WSAA, Australia.

According to this report, the ‘foundational premise of IWCM is that the successful achievement of on-the-ground delivery outcomes is critically dependent on ensuring all the enabling outcomes are in place before the problem-solving phase commences’.

WSAA’s two main proactive campaigns are as follows:

All options on the table campaigns promote innovation and raise awareness about alternative solutions to a problem. The circular economy management systems are a step closer to closed-loop solutions and a move away from the current linear approaches to water supply–demand management systems.

WSAA’s recent report by Skinner [3] summarises the best practice requirements for water utilities and recommends the following:

-

Embracing collaboration;

-

Focusing on customer and community;

-

Being outcome driven;

-

Having a system design that is owned by all stakeholders involved in the water cycle management;

-

Operating from planning to management;

-

Taking a whole-of-water cycle approach to planning, with all supply and demand options on the table;

-

Taking into account all options related to water, wastewater and drainage services;

-

Taking into account the environmental, cultural, social and economic dimensions of the area;

-

Closely integrating strategic and statutory land-use planning and water planning;

-

Supporting a circular economy by maximising efficiency and working towards regenerative outcomes;

-

Being fit-for-purpose—can be suited to different scales (e.g., catchment, region and precinct) and context (places and communities);

-

Being ambitious and transformative in striving for the broader outcomes of the sustainable development goals.

3. IWMF—Victoria, Australia

IWCM is referred to by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria (DELWP-Vic) as IWMF [6] for urban water planning and shared decision making throughout Victoria. IWMF has its roots in stakeholder engagement. The IWCM interpretation framework outlines how greater community value can be delivered by consistent and strategic collaboration within the water sector, including water corporations, local governments and catchment management authorities, and by links with organisations involved in land-use planning.

In Victoria, IWMF emphasises the importance of stakeholder awareness and governance. The IWM planning process details the structure and criteria for developing an IWM plan. Shared outcomes, integrated servicing options and cost allocations all refer to Water CI, with an overarching value proposition and collaboration.

The IWMF interpretation (see Figure 3) has six subcomponents and falls within the two main categories of the STEEPI framework: (1) social inclusion and (2) governance. The social aspect of the IWMF incorporates (a) communicating the value of IWM, (b) communicating the rationale for collaboration and (c) community values reflected in IWMF plans. The governance aspect of the IWMF incorporates (d) the contribution of IWM planning to water management activities, (e) IWM opportunities in plans and (f) consistency in the governance approach to provide support and guidance for collaborative planning [6][7][8].

Figure 3. IWMF in Victoria, Australia.

Implementing IWMF requires stakeholders to commit, while accountabilities clearly define the roles and responsibilities of the organisation and collaborating organisations. Purpose-designed IWM forums have been formed in Victoria, 5 Metropolitan Melbourne Forums and 11 Regional Victoria Forums, with some overlap in boundaries towards the outer edge of the Metropolitan Melbourne boundaries (information extracted from the interactive Hydra Map). These forums are formed under the governance category of IWMF, consistent with a governance approach.

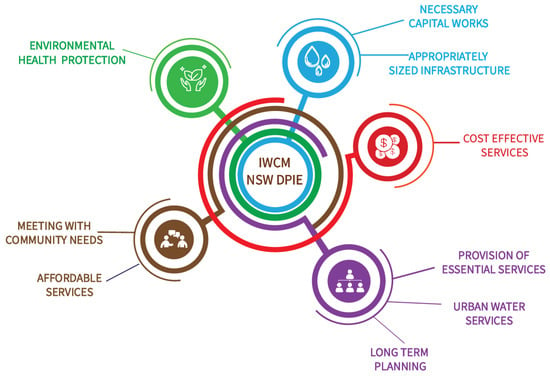

4. IWCM in NSW, Australia

The NSW Department of Planning and Environment defines IWCM as a long-term planning tool (30-year strategy) to identify and plan for an appropriately sized infrastructure. IWCM in NSW is rolled out as a policy and is funded by the Department of Planning and Environment (DPE). The funding requires IWCM plans to address all criteria in the checklist document. An extended version of the ‘IWCM Strategy Checklist’ updated in October 2019 provides exact details of what an IWCM strategy should comprise and why. The IWCM strategy development guidelines document was published to ensure that the strategies align with the NSW State Plan 2021 goals and objectives and that they are consistent state-wide and measurable [9].

The nine subtopics ensure that the necessary capital works are appropriately sized; the water infrastructure and services provided are appropriate, affordable and cost-effective urban water services that meet the water community needs and protect public health and the environment. The IWCM in NSW is represented in Figure 4, per the six STEEPI categories. The STEEPI categories addressed by IWCM in NSW are (1) social inclusion, (2) economy, (3) environment, (4) politics and (5) infrastructure.

Figure 4. IWCM in New South Wales, Australia.

The NSW Office of Water (NOW) developed the IWCM’s Best Practice Management (BPM) framework to ensure sound long-term planning, asset management, operation and maintenance; appropriate levels of service and community involvement; and the fair pricing of services, with strong pricing signals, full-cost recovery and affordable water and sewerage services, without wasteful ‘gold plating’ [10].

Further, each utility must closely involve its community in its implementation as required by the NSW BPM Framework: the IWCM Strategy and Financial Plan. A required outcome for each water supply and sewerage infrastructure is to have a strategic business plan, water conservation measures, a drought management plan and performance monitoring. Pricing outcomes must include full-cost recovery, appropriate residential charges, appropriate non-residential charges, a development servicing plan with commercial developer charges, strong pricing signals (with at least 75 percent of residential revenue from usage charges), an appropriate trade waste regulation policy and approvals and appropriate trade waste fees and charges. A particular emphasis is placed on consultation and stakeholder engagement throughout the IWCM policy-making process and implementation process.

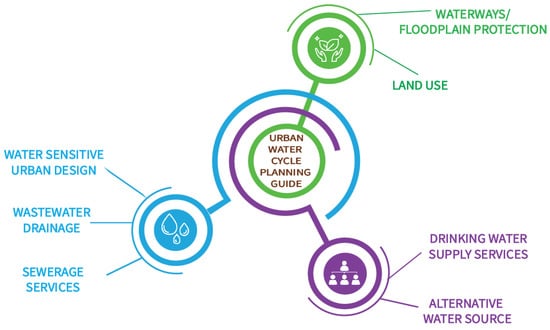

5. Urban Water Cycle Planning Guide

The Urban Water Cycle Planning Guide (UWCPG), an online resource, was developed collaboratively by the Barwon Region IWCM group, funded by Water Research Australia and Water Smart Fund. The diagram in Figure 5 illustrates the influence of the legal frameworks that guide the development of water management planning. The guide provides direction to enhance liveability outcomes through the whole-of-water cycle management approach by considering water-sensitive urban design criteria.

Figure 5. IWCM components in a UWCG process.

The UWCPG defines the IWCM strategy as developing the progressive conceptual model to detailed planning, where each aspect is considered in a specific sequence. The process also provides guidance on identifying factors influencing the planning process of IWCM policies, strategies, objectives, masterplan designs and delivery.

The UWCPG covers seven subcomponents of an IWCM plan, addressing waterways and floodplains; major drainage; land-use planning; water-sensitive urban design; drinking water supply servicing—LoS; sewerage services; and alternative (fit-for-purpose) water sources. These seven components are categorised in Figure 5 in three of the six STEEPI categories: (1) environment, (2) politics and (3) infrastructure. UWCPG particularly focuses on providing a higher LoS by managing the water supply–demand infrastructure due to changes in land-use planning and climate variations.

6. Comparative Analysis

Researchers compared the IWCM interpretations discussed above and looks through the STEEPI framework’s lens. A comparison of IWCM interpretations in Table 1 reveals the importance of the six STEEPI categories adapted for IWCM practices to address local challenges.

Table 1. Comparison of IWCM interpretations in the STEEPI framework.

| IWCM | IWRM-GWP | Waterwise Cities | One Water | TWM | WFD | PC | WSAA | IWCM | IWMF | UWCPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S—Social Inclusion | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| T—Technology | √ | √ | ||||||||

| E—Water Economics | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| E—NRM | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| P—Governance | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| I—Water CI | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Social inclusion is addressed by 9 of the 10 interpretations. Although social inclusion is not addressed directly in the UWCMG, forming partnerships and collaborating externally and internally within the organisation captures the essence of stakeholder engagement practices and inclusiveness. All nine interpretations capture social inclusion as stakeholder engagement or involvement. Additionally, IWRM includes capacity building, WSAA and One Water’s pathway via the design of liveable cities. IWCM in NSW is concerned with meeting community needs and providing affordable services, and IWMF in Victoria entails communicating the values and rationale of an IWCM for greater adoption.

Technology has time and again proved to be a major disruptor and one that impacts all other categories. For example, it did not win a spot for itself as a major challenge until the drawn-out COVID-19 pandemic, forcing researchers to rethink how researchers work and address challenges. Exponential technological growth and the increasing dependence on technology are changing how researchers perceive the term ‘technology’. Two of the ten IWCM interpretations consider technology challenges strong enough to merit their own category. They are Water-Wise Cities by IWA and TWM in the US. TWM addresses technology as data collection requirements to identify climate variability and climate change impacts. In contrast, the Water-Wise Cities framework examines technology from a WSUD perspective to address design challenges in order to enable regenerative services, enable liveability and modify and adapt materials to reduce environmental impacts. The Water-Wise Cities framework notes services and materials as technology and drives the much-needed shift of expanding the definition of technology.

Five of the ten IWCM interpretations note the economics of water management as a critical requirement of developing an IWCM interpretation. The IWRM interpretations by GWP and Water-Wise Cities focus on water governance measures, leaving water economics to regional IWCM interpretations, the World Bank and political leaders. The WSAA’s focus on liveability leans towards the social and cultural aspects of water management. In contrast, IWMF drives water governance through stakeholder engagement and collaboration, leaving water economics out of the primary equation, but it is considered an expected outcome. UWCPG is a planning tool focused on delivering IWCM interpretations. Water economics is addressed by five IWCM interpretations as cost savings (WFD), achieving technological resilience (One Water), ensuring cost effectiveness throughout the lifecycle of the infrastructure (TWM), a blue–green economic system with the least-cost option (PC) and cost-effective service provision (IWCM in NSW). Water economics does not capture job creation as its integral part, but it primarily focuses on cost savings and cost effectiveness.

Environment (NRM) is addressed by seven of the ten IWCM interpretations. The WFD, PC and IWMF address NRM by following sustainability principles, but they do not specify or clarify where or how these principles are incorporated. Environment is an assumed overarching outcome or secondary outcome. For example, the core categories are addressed to manage an infrastructure project: asset management, finance and governance. Sustainable procurement is a desired outcome but not mandated. Each of the seven interpretations captures the protection of the environment as its component. Only IWRM promotes environment as a legitimate water user, whereas Water-Wise Cities, One Water and UWCPG note flood management/protection and environmental health as their core component. One Water and TWM, the IWCM interpretations in the US, are the only ones that capture climate resilience and address climate variability as their core components. Emissions from ongoing operations are not considered for Water CI.

Governance is acknowledged and addressed by all 10 IWCM interpretations as the most important management criterion, and it is considered vital to implementing an IWCM interpretation. Governance is predominantly used for planning, community engagement/involvement and education. The complex political influences on these components are discounted from the equation.

Water CI is addressed in 5 of the 10 IWCM interpretations, even though the importance of Water CI is significant. The IWRM, Water-Wise Cities, WSAA and IWMF concepts leave it to local and regional IWCM interpretations to identify infrastructure needs. TWM captures infrastructure needs as an inherent requirement to implement the first five categories of the STEEPI framework. One Water, WFD and PC capture Water CI as water supply and demand management infrastructure and related services. IWCM in NSW considers the size of an infrastructure as an essential part of infrastructure development, whereas UWCPG focuses on WSUD and wastewater services.

References

- Productivity Commission. Integrated Urban Water Management—Why a Good Idea Seems Hard to Implement? Productivity Commission Review. 2020. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/water-cycle#panel (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Productivity Commission. Water Cycle Webinar PC—Greening out Cities. 10 August 2020. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/water-cycle/water-cycle-webinar.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Skinner, R.; Satur, P. Integrated Water Management: Principles and Best Practice for Water Utilities; Summary paper, prepared for the Water Services Association of Australia by Monash Sustainable Development Institute; Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2020.

- Water Services Association of Australia. Urban Water Supply Options for Australia—All Options on Table; Water Services Association of Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2020.

- Jazbec, M.; Mukheibir, P.; Turner, A. Transitioning the Water Industry with the Circular Economy; Final 12102020; Water Services Association of Australia, Institute of Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2020.

- DELWP-Vic (2017), DELWP-IWM-Framework-FINAL-FOR-WEB. 2017; Web Publication by Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. Available online: https://www.water.vic.gov.au/liveable/integrated-water-management-program (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Victorian Planning Authority. PSP Guidelines Notes—Integrated Water Management (VIC). 2013. Available online: https://vpa.vic.gov.au/wp-content/Assets/Files/PSP_Guidelines_Notes_Integrated_Water_Management%5B1%5D.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Water Services Association of Australia. WSAA: IWM Case Study 2—Victorian IWM Framework. Available online: https://www.wsaa.asn.au/publication/iwm-case-study-2-victorian-iwm-framework (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Samra, S.; McLean, C. Best Practice Management of Water Supply and Sewerage Guidelines; Department of Water and Energy: Orange, Australia, 2007.

- NOW. NSW—Best Practice Management for Water Supply and Sewerage Framework Summary—Flowchart. 2007. Available online: https://www.industry.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/146997/BPMF.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2023).

More

Information

Subjects:

Water Resources

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

839

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 Apr 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No