Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Huawei Zhang | -- | 2792 | 2023-04-18 11:33:54 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | Meta information modification | 2792 | 2023-04-19 04:20:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Xu, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Liu, Y.; Bai, X.; Zhang, H. Fusarium-Derived Secondary Metabolites with Antimicrobial Effects. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43170 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Xu M, Huang Z, Zhu W, Liu Y, Bai X, Zhang H. Fusarium-Derived Secondary Metabolites with Antimicrobial Effects. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43170. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Xu, Meijie, Ziwei Huang, Wangjie Zhu, Yuanyuan Liu, Xuelian Bai, Huawei Zhang. "Fusarium-Derived Secondary Metabolites with Antimicrobial Effects" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43170 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Xu, M., Huang, Z., Zhu, W., Liu, Y., Bai, X., & Zhang, H. (2023, April 18). Fusarium-Derived Secondary Metabolites with Antimicrobial Effects. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43170

Xu, Meijie, et al. "Fusarium-Derived Secondary Metabolites with Antimicrobial Effects." Encyclopedia. Web. 18 April, 2023.

Copy Citation

Fungal microbes are important in the creation of new drugs, given their unique genetic and metabolic diversity. As one of the most commonly found fungi in nature, Fusarium spp. has been well regarded as a prolific source of secondary metabolites (SMs) with diverse chemical structures and a broad spectrum of biological properties. However, little information is available concerning their derived SMs with antimicrobial effects. By extensive literature search and data analysis, as many as 185 antimicrobial natural products as SMs had been discovered from Fusarium strains by the end of 2022.

Fusarium

secondary metabolite

antimicrobial effect

antibacterial

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial agents play a significant role in the treatment of infectious diseases caused by pathogenic microorganisms with various modes of action. Since the fortuitous discovery of penicillin in 1928, hundreds of antibiotics have been approved for clinical use. However, some of these drugs have become less efficacy or unavailability simultaneously owing to the development of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), in which a pathogenic microbe evolves a survival mechanism that protects the drug target by modification or replacement, or degradation or modification of the antibiotic to render it harmless, such as MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), multidrug-resistant S. aureus (MDRS), VREF (vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium), CRKP (cephalosporin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae) [1]. Antimicrobial resistance has become an increasing threat to human health and is widely considered to be the next global pandemic [2]. Therefore, it is an urgent need for the discovery of new antimicrobial drugs with novel structural scaffolds and new modes of action.

2. Antibacterial Secondary Metabolites

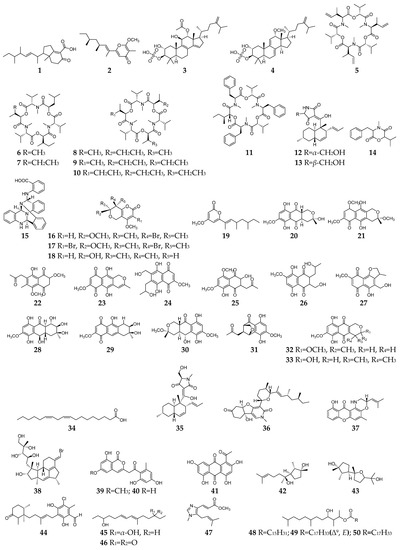

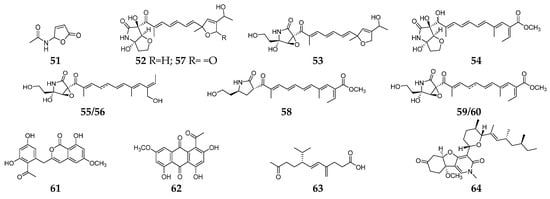

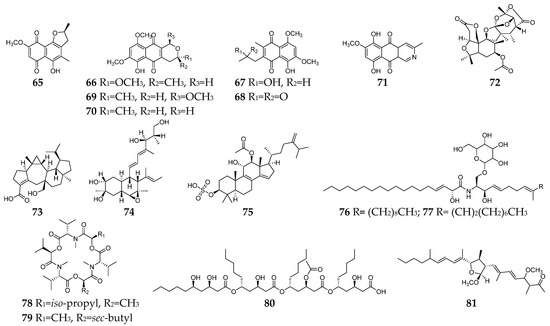

Bacterial infection is a common clinical disease that can affect a variety of organs and tissues. Fusarium-derived antibacterial SMs have a wide array of structural motifs, most of which are polyketides, followed by alkaloids, terpenoids, and cyclopeptides. According to antibacterial properties, these chemicals are divided into three groups, including anti-Gram-positive bacterial SMs (1–50, Figure 1), anti-Gram-negative bacterial SMs (51–64, Figure 2) and both anti-Gram-positive and anti-Gram-negative bacterial SMs (65–81, Figure 3).

Figure 1. Fusarium-derived anti-Gram-positive bacterial SMs (1–50).

Figure 2. Fusarium-derived anti-Gram-negative bacterial SMs (51–64).

Figure 3. Fusarium-derived anti-Gram-positive and anti-Gram-negative bacterial SMs (65–81).

2.1. Anti-Gram-Positive Bacterial SMs

Fifty Fusarium-derived SMs (1–50, Figure 1) had been characterized and displayed various bactericidal effects on Gram-positive strains, such as Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, multidrug-resistant S. aureus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bacillus subtilis, etc. Fusariumins C (1) and D (2) are two new polyketides produced by an endophytic strain F. oxysporum ZZP-R1 from coastal plant Rumex midair Makino displayed medium effect on S. aureus with MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) values of 6.25 and 25.0 μM, respectively [3]. Two triterpene sulfates (3 and 4) isolated from F. compactum exhibited weak activity toward S. aureus and Streptococcus strains in the range of 6–50 µg/mL [4]. Enniatins (5–10), a group of antibiotics commonly synthesized by various Fusarium strains, are six-membered cyclic depsipeptides formed by the union of three molecules of D-α-hydroxyisovaleric acid and three N-methyl-L-amino acids [5]. Three enniatins (8–10), beauvericin A (11) and trichosetin (12) were obtained from an endophytic fungus, Fusarium sp. TP-G1 and showed moderate anti-S. aureus and anti-methicillin-resistant S. aureus effects with MIC values in the range of 2–16 µg/mL [6]. Two enantiomers (12 and 13) were separated from the culture broth of F. oxysporum FKI-4553 and found to have an inhibitory effect on the undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase activity of S. aureus with IC50 values of 83 and 30 µM, respectively [7].

Lateritin (14) derived from Fusarium sp. 2TnP1–2 showed anti-S. aureus activity at 2 µg per disc with 7 mm of inhibition zone [8]. A new polycyclic quinazoline alkaloid (15) displayed moderate antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus and multidrug-resistant S. aureus, with the same MIC value of 6.25 µg/mL [9]. Three pyranopyranones (16–18) showed weak inhibitory activities against S. aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, and multidrug-resistant S. aureus [10]. Compound 19 was a new pyran-2-one with weak activity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus and was shown to be the inhibitor of the quorum-sensing mechanism of S. aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [11]. Trans-dihydrofusarubin (20) and seven analogs (21–27) had significant antibiotic activity against S. aureus (MIC values < 4 µg/mL), and compounds 26 and 27 exhibited potent activity against S. pyogenes [12]. Five naphthoquinones 28–32 showed anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis activity with MICs ranging from 25 to 50 µg/mL [13]. Compounds 32 and 33 displayed moderate antibacterial activity against S. aureus and potent activities against B. cereus and S. pyogenes with MIC values of <1 µg/mL as compared to ciprofloxacin, whose MIC value was 0.15 and 10 µg/mL, respectively [14].

Linoleic acid (34) and epi-equisetin (35) had certain inhibitory activity against S. aureus and multidrug-resistant S. aureus [15]. (−)-4,6′-anhydrooxysporidinone (36) was obtained from F. oxysporum and showed weak anti-multidrug-resistant S. aureus and moderate anti-B. subtilis effects [16]. Fusaroxazin (37), a novel antimicrobial xanthone derivative from F. oxysporum, possessed significant antibacterial activity towards S. aureus and B. cereus, with MIC values of 5.3 and 3.7 µg/mL, respectively [17]. Neomangicol B (38) isolated from the mycelial extract of a marine Fusarium strain was found to inhibit B. subtilis growth with a potency similar to that of the antibiotic gentamycin [18]. Three aromatic polyketides (39–41) were produced by strain F. proliferatum ZS07 and possessed potent antibacterial activity against B. subtilis with the same MIC values of 6.25 µg/mL [19]. Two sesterterpenes (42 and 43) produced by F. avenaceum SF-1502 displayed stronger antibacterial activity against B. megaterium than positive controls (ampicillin, erythromycin, and streptomycin) [20]. 4,5-Dihydroascochlorin (44) had strong antibacterial activity towards Bacillus megaterium [21]. Fusariumnols A (45) and B (46) were two novel anti-S. epidermidis aliphatic unsaturated alcohols isolated from F. proliferatum 13,294 [22]. Fungerin (47) displayed weak antibacterial activity against S. aureus and S. pneumoniae [23]. Compounds 48–50 were purified from F. oxysporum YP9B and showed a potent inhibitory effect on S. aureus, E.faecalis, S. mutans, B. cereus, and M. smegmatis with MICs of less than 4.5 µg/mL [24].

2.2. Anti-Gram-Negative Bacterial SMs

Butenolide (51) was a fusarium mycotoxin from unknown origin strain Fusaium sp. and showed selective inhibitory activity against E. coli [25]. Extensive chemical investigation of the endophytic fungus F. solani JK10 afforded nine 2-pyrrolidone derivatives (52–60), which displayed antibacterial activity against E. coli with MIC values of 5–10 µg/mL. Particularly, three lucilactaene analogs (52–54) had strong inhibitory effects on Acinetobacter sp., comparable to the positive control streptomycin [26]. One new aromatic polyketide, karimunones B (61), together with compounds 62 and 63, was obtained from sponge-associated Fusarium sp. KJMT.FP.4.3 and exhibited anti-multidrug resistant Salmonella enterica ser. Typhi activity with a MIC of 125 µg/mL [27]. Fusapyridon A (64) is produced by an endophytic strain, Fusarium sp. YG-45 demonstrated moderate antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa with a MIC value of 6.25 µg/mL [28].

2.3. Both Anti-Gram-Positive and Anti-Gram-Negative Bacterial SMs

Seventeen Fusarium-derived SMs (65–81, Figure 3) were shown to have both anti-Gram-positive and anti-Gram-negative activity. Seven naphthoquinones (65–71) demonstrated moderate activities against an array of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as B. megaterium, B. subtilis, C. perfringens, E. coli, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and S. pyogenes [12][20][29][30]. The mechanism of action (MoA) study indicated that compounds 66 and 71 could stimulate the oxygen consumption of bacterial cells and induce cyanide-insensitive oxygen consumption, which results in the generation of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide [31]. Compounds 72–75 were polycyclic terpenoids, respectively, produced by three Fusarium strains [32][33][34]. Compound 72 had significant activity against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa with a MIC value of 6.3 µg/mL, and 73 showed moderate activities against Salmonella enteritidis and Micrococcus luteus with MIC values of 6.3 and 25.2 µg/mL, respectively, while 74 showed a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity and 75 exhibited moderate antibacterial activities against S. aureus and E. coli with the same MIC value of 16 µg/mL. Two xanthine oxidase inhibitory cerebrosides (76 and 77) were identified and purified from the culture broth of Fusarium sp. IFB-121 and showed strong antibacterial activities against B. subtilis, E. coli, and P. fluorescens with MICs of less than 7.8 µg/mL [35]. Enniatins J1 (78) and J3 (79) were two hexadepsipeptides with an array of antibacterial activity toward C. perfringens, E. faecium, E. coli, S. dysenteriae, S. aureus, Y. enterocolitica, and lactic acid bacteria except for B. adolescentis [36]. Halymecin A (80) was produced by a marine-derived Fusarium sp. FE-71-1 and exhibited a moderate inhibitory effect on E. faecium, K. pneumoniae, and P. vulgaris with the MIC value of 10 µg/mL [37]. Fusaequisin A (81) was isolated from rice cultures of F. equiseti SF-3-17 and found to have moderate antimicrobial activity against S. aureus NBRC 13,276 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 15,442 [38].

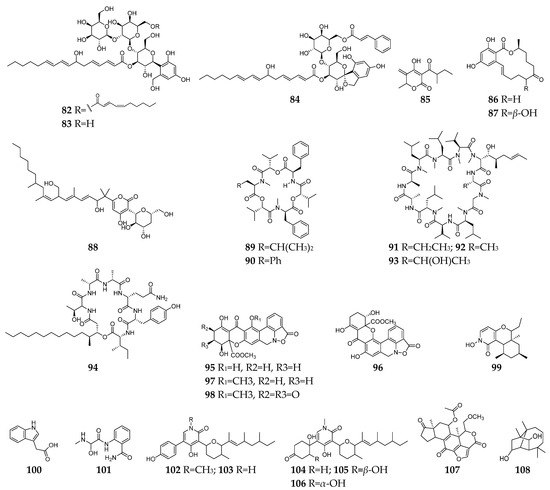

3. Antifungal Secondary Metabolites

Invasive fungal infections are very common in immunocompromised patients (such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome and organ transplantation) and have become a global problem resulting in 1.7 million deaths every year [39][40][41]. Furthermore, the overuse of antifungal agents increases opportunistic pathogen resistance, which had been listed as one of the dominant threats by the World Health Organization in 2019. Therefore, the urgent need for new antimycotics with novel targets is undeniable. Till the end of 2022, twenty-seven antifungal SMs (82–108, Figure 4) had been discovered from Fusarium strains. Compounds 82–84 are three anti-C. albicans glycosides belong to the papulacandin class [42][43]. The MoA study suggested that compound 82 is an inhibitor of glutamine synthetase (GS) enzyme for (l,3)-β-glucan biosynthesis [42]. CR377 (85) was a new α-furanone derivative from an endophytic Fusarium sp. CR377 and showed a similar antifungal effect on C. albicans with nystatin [44]. Compounds 86 and 87 were two zearalenone analogs and exhibited weak activity against Cryptococcus neoformans [45]. Neofusapyrone (88) produced by a marine-derived Fusarium sp. FH-146 displayed moderate activity against A. clavatus F318a with a MIC value of 6.25 µg/mL [46]. Six cyclic depsipeptides 89–94 had been isolated from several Fusarium strains and found to have significant inhibitory activities against pathogenic fungi, such as C. albicans [47], C. glabrata, C. krusei, V. ceratosperma, and A. fumigates [48]. Cyclosporin A (91) has long been recognized as an immunosuppressant agent and could inhibit the growth of sensitive fungi after their germination [49][50]. Parnafungins A-D (95–98) were isoxazolidinone-containing natural products and demonstrated broad-spectrum antifungal activity with no observed activity against bacteria. The targeted pathway of these alkaloids was determined to be the mRNA 3`-cleavage and polyadenylation process [51][52]. One N-hydroxypyridine derivative (99) showed antifungal activity against C. albicans and Penicillium chrysogenum with MICs of 16 and 8 µg/mL, respectively [53]. Indole acetic acid (100) exhibited activity against the fluconazole-resistant C. albicans (MIC = 125 µg/mL) [54].

Figure 4. Fusarium-derived antifungal SMs (82–108).

Fusaribenzamide A (101) possessed a significant anti-C. albicans activity with MIC of 11.9 µg/disc compared to nystatin (MIC = 4.9 µg/disc) [55]. Three pyridone derivatives (102–104) displayed significant activities against multidrug-sensitive S. cerevisiae 12geneΔ0HSR-iERG6, and the MoA study indicated that these substances have a potent inhibitory effect on NADH-cytochrome C oxidoreductase [56]. Compounds 105–107 were derived from strain F. oxysporum N17B, and the former (105 and 106) showed selective fungistatic activity against Aspergillus fumigatus, and the latter (107) had selective potent activity against C. albicans through inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [57]. Culmorin (108) displayed remarkable antifungal activity against both marine (S. marina, M. pelagica) and medically relevant fungi (A. fumigatus, A. niger, C. albicans, T. mentagrophytes) [58][59].

4. Both Antibacterial and Antifungal Secondary Metabolites

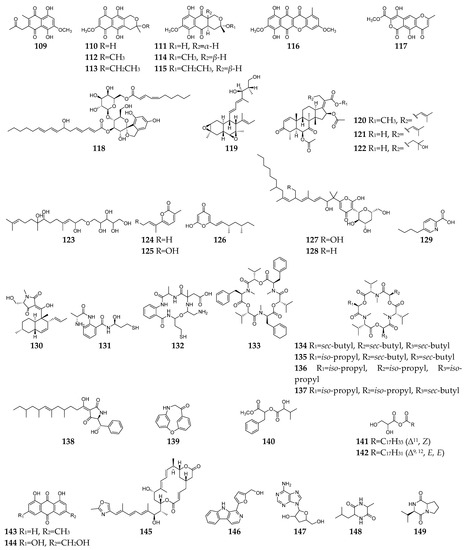

Till the end of 2022, forty-one SMs (109–149, Figure 5) with both antibacterial and antifungal effects had been discovered from Fusarium spp. Among these Fusarium-derived 1,4-naphthoquinone analogs (109–115), compound 109 showed potent anti-Gram-positive bacteria activity against B. cereus and S. pyogenes with MIC of <1 µg/mL and anti-C. albicans activity with IC50 (the half maximal inhibitory concentration) of 6.16 µg/mL [13], and 110–115 demonstrated moderate inhibitory effects on S. aureus, C. albicans, and B. subtilis [60]. Bikaverin (116) was found to have anti-E. coli and antifungal (P. notatum, Alternaria humicola, and A. flavus) activity [47][61][62]. Lateropyrone (117) was the same SM as F. acuminatum, F. lateritium, and F. tricinctum and displayed good antibacterial activity against B. subtilis, S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and vancomycin-resistant of E. faecalis and significant inhibitory activity towards the growth of C. albicans [63][64][65][66]. BE-29,602 (118) was a novel antibiotic of the papulacandin family, showing good activity against C. albicans, S. cerevisiae, S. pombe with MIC values < 1 µg/mL and moderate activity against B. subtilis and P. chrysogenum with the MIC values < 8 µg/mL [43][67]. Fusarielin A (119) was a meroterpenoid with moderate antifungal activities against A. fumigatus and F. nivale and weak antibacterial effect on S. aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, and multidrug-resistant S. aureus [10][68]. Three helvolic acid derivatives (120–122) displayed potent antifungal and antibacterial activities against B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli, B. cinerea, F. Graminearum, and P. capsica [69]. Fusartricin (123) had moderate antimicrobial activity against E. aerogenes, M. tetragenu, and C. albicans with the same MIC value of 19 µM [33].

Figure 5. Fusarium-derived antibacterial and antifungal SMs (109–149).

Compounds 124–128 are pyrone family members and showed antimicrobial activity against bacteria (such as B. subtilis, S. aureus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, C. kefyr, and P. aeruginosa) and fungi (such as A. clavatus, Geotrichum candidum, C. albicans, M. albican, and S. cerevisiae) [46][70][71][72][73]. Fusaric acid (129), one of the most significant mycotoxins from Fusarium strains, displayed a broad spectrum of moderate antimicrobial activity against Bacillus species, Acinetobacter baumannii, Phytophthora infestans, etc. [74][75][76]. Equisetin (130) was shown to be active against several strains of Gram-positive bacteria (B. subtilis, Mycobacterium phlei, S. aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, and S. erythraea) and the Gram-negative bacteria Neisseria perflava at concentrations of 0.5–4.0 µg/mL, as well as antifungal activity toward P. syringae and R. cerealis [77][78]. Fusarithioamides A (131) and B (132) demonstrated antibacterial potential towards B. cereus, S. aureus, and E. coli compared to ciprofloxacin and selective antifungal activity towards C. albicans compared to clotrimazole [79][80]. Beauvericin (133) and enniatins A, A1, B and B1 (134–137) are cyclic hexadepsipeptides with a wide array of highly antimicrobial activities against bacteria (such as B. subtilis, S. aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, etc.) and fungi (such as C. albicans, B. bassiana, T. harzianum, etc.) [81][82][83][84][85]. Unlike most antibiotics, cell organelles or enzyme systems are the targets of the antibiotic 133 [86]. As a drug efflux pump modulator, furthermore, compound 133 had the capability to reverse the multi-drug resistant phenotype of C. albicans by blocking the ATP-binding cassette transporters and to repress the expression of many filament-specific genes, including the transcription factor BRG1, global regulator TORC1 kinase [87]. Fusaramin (138) displayed anti-Gram-positive and anti-Gram-negative bacterial activity and could inhibit the growth of S. cerevisiae 12geneΔ0HSR-iERG6 [56]. Compounds 139–142 were isolated from F. oxysporum YP9B and exhibited a significant antimicrobial effect against bacterial and fungi at concentrations of 0.8–6.3 µg/mL [24]. Seven SMs (143–149) were separated from an endophytic fungus F. equiseti, and showed antibacterial (such as B. subtilis, S. aureus, B. megaterium) and anti-C. albicans activities [88].

5. Antiviral Secondary Metabolites

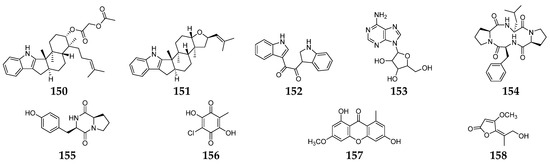

The infections by viruses in humans resulted in millions of deaths globally and are accountable for viral diseases, including HIV/AIDS, hepatitis, influenza, herpes simplex, common cold, etc. [89]. The emergence of new viruses like Ebola and coronaviruses (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2) emphasizes the need for more innovative strategies to develop better antiviral drugs. Twenty-three Fusarium-derived SMs (64, 99, 105, 135–137, 140–142, 144–147, 149–158, Figure 6) had been shown to have antiviral effects. The isolation of fusaricide (99) was guided by the Rev (regulation of virion expression) binding assay [53]. Fusapyridon A (64) and oxysporidinone (105) displayed antiviral activity against the coronavirus (HCoV-OC43) with IC50 values of 13.33 and 6.65 μM, respectively [90]. Their enniatins (135–137) were found to protect human lymphoblastoid cells from HIV-1 infection with an in vitro “therapeutic index” of approximately 200 (IC50 = 1.9, EC50 = 0.01 µg/ mL, respectively) [91]. The antiviral activity against HSV type-1 was determined to be 0.312 µM for compound 140 and 1.25 µM for 141 and 142 [24]. Three indole alkaloids (150–152) were obtained from a marine-derived Fusarium sp. L1 and exhibited inhibitory activity against the Zika virus (ZIKV) with EC50 values of 7.5, 4.2, and 5.0 μM, respectively [92]. A chemical study of an endophytic fungus F. equiseti led to the isolation of compounds 144–147 and 153–157, of which 149 and 157 showed good potency against hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease, while 144 and 155 were the most potent hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitors [88]. Coculnol (158) was a penicillic acid from a coculture of F. solani FKI-6853 and Talaromyces sp. FKA-65 displayed an inhibitory effect on A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) with an IC50 value of 283 µg/mL [93].

Figure 6. Fusarium-derived antiviral SMs (150–158).

6. Antiparasitic Secondary Metabolites

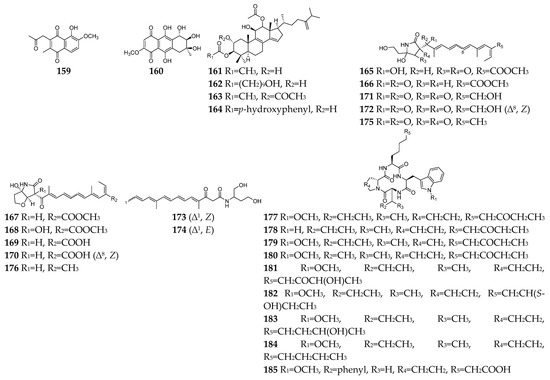

Parasitic diseases caused by protozoa, helminths and ectoparasites affect millions of people each year and result in substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in tropical regions [94]. Therefore, new antiparasitic agents are urgently needed to treat and control these diseases. A total of 39 antiparasitic SMs (23, 28, 29, 59, 108, 93, 116, 133–137, 159–185, Figure 7) had been isolated and characterized from Fusarium strains. Five naphthoquinones (23, 29, 30, 109, and 159) and one anthraquinone (160) showed weak inhibitory activity toward the most deadly malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum K1 with IC50 values in the range 9.8–26.1 µM [95]. However, compound 93 displayed significant antiplasmodial activity toward P. falciparum (D6 clone) with an IC50 value of 0.34 µM [48]. Bikaverin (116) was specifically effective against Leishmania brasiliensis, which is one of the main causes of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Americas [96]. Beauvericin (133) was reported to inhibit Trypanosoma cruzi with an IC50 value of 2.43 μM and L. braziliensis with an EC50 value of 1.86 μM [97][98]. In addition to antibacterial and antifungal effects, enniatins (134–137) exhibited mild anti-leishmanial activity by inhibition of the activity of thioredoxin reductase enzyme of P. falciparum [5]. Integracides F, G, H, and J (161–164) were also shown to have stronger anti-leishmanial activity towards L. donovani than the positive control pentamidine (IC50 = 6.35 µM) [99]. Among twelve lucilactaene derivatives (165–176), compounds 166–168 showed very potent antimalarial activity toward P. falciparum (IC50 = 0.0015, 0.15, and 0.68 μM, respectively) [100][101][102]. Structure−activity relationship study suggested that epoxide is extremely detrimental, and demethylation of the lucilactaene methyl ester and formation of the free carboxylic acid group resulted in a 300-fold decrease in activity. Nine cyclic tetrapeptides (177–185) are apicomplexan histone deacetylase (HDA) inhibitors [103][104][105]. Particularly, compound 177 was an excellent inhibitory agent (IC50 < 2 nM) and showed in vivo high efficacy against P. berghei malaria in mice at less than 10 mg/kg.

Figure 7. Fusarium-derived antiparasitic SMs (159–185).

References

- Denissen, J.; Reyneke, B.; Waso-Reyneke, M.; Havenga, B.; Barnard, T.; Khan, S.; Khan, W. Prevalence of ESKAPE pathogens in the environment: Antibiotic resistance status, community-acquired infection and risk to human health. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 244, 114006.

- Nadimpalli, M.L.; Chan, C.W.; Doron, S. Antibiotic resistance: A call to action to prevent the next epidemic of inequality. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 187–188.

- Chen, J.; Bai, X.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Fusariumins C and D, two novel antimicrobial agents from Fusarium oxysporum ZZP-R1 symbiotic on Rumex madaio Makino. Fitoterapia 2019, 134, 1–4.

- Brill, G.M.; Kati, W.M.; Montgomery, D.; Karwowski, J.P.; Humphrey, P.E.; Jackson, M.; Clement, J.J.; Kadam, S.; Chen, R.H.; McAlpine, J.B. Novel triterpene sulfates from Fusarium compactum using a rhinovirus 3C protease inhibitor screen. J. Antibiot. 1996, 49, 541–546.

- Zaher, A.M.; Makboul, M.A.; Moharram, A.M.; Tekwani, B.L.; Calderon, A.I. A new enniatin antibiotic from the endophyte Fusarium tricinctum Corda. J. Antibiot. 2015, 68, 197–200.

- Shi, S.; Li, Y.; Ming, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Luo, M. Biological activity and chemical composition of the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. TP-G1 obtained from the root of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2018, 12, 549–556.

- Inokoshi, J.; Shigeta, N.; Fukuda, T.; Uchida, R.; Nonaka, K.; Masuma, R.; Tomoda, H. Epi-trichosetin, a new undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase inhibitor, produced by Fusarium oxysporum FKI-4553. J. Antibiot. 2013, 66, 549–554.

- Du, Z.; Song, C.; Yu, B.; Luo, X. Secondary metabolites produced by Fusarium sp. 2TnP1-2, an endophytic fungus from Trewia nudiflora. Chin. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 18, 452–456.

- Nenkep, V.; Yun, K.; Son, B.W. Oxysporizoline, an antibacterial polycyclic quinazoline alkaloid from the marine-mudflat-derived fungus Fusarium oxysporum. J. Antibiot. 2016, 69, 709–711.

- Nenkep, V.; Yun, K.; Zhang, D.; Choi, H.D.; Kang, J.S.; Son, B.W. Induced production of bromomethylchlamydosporols A and B from the marine-derived fungus Fusarium tricinctum. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 2061–2063.

- Alfattani, A.; Marcourt, L.; Hofstetter, V.; Queiroz, E.F.; Leoni, S.; Allard, P.M.; Gindro, K.; Stien, D.; Perron, K.; Wolfender, J.L. Combination of pseudo-LC-NMR and HRMS/MS-based molecular networking for the rapid identification of antimicrobial metabolites from Fusarium petroliphilum. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 725691.

- Baker, R.A.; Tatum, J.H.; Nemec, S., Jr. Antimicrobial activity of naphthoquinones from Fusaria. Mycopathologia 1990, 111, 9–15.

- Kornsakulkarn, J.; Dolsophon, K.; Boonyuen, N.; Boonruangprapa, T.; Rachtawee, P.; Prabpai, S.; Kongsaeree, P.; Thongpanchang, C. Dihydronaphthalenones from endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. BCC14842. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 7540–7547.

- Shah, A.; Rather, M.A.; Hassan, Q.P.; Aga, M.A.; Mushtaq, S.; Shah, A.M.; Hussain, A.; Baba, S.A.; Ahmad, Z. Discovery of anti-microbial and anti-tubercular molecules from Fusarium solani: An endophyte of Glycyrrhiza glabra. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 122, 1168–1176.

- Chen, C.; Luo, X.; Li, K.; Guo, C.; Li, J.; Lin, X. Antibacterial secondary metabolites from a marine sponge-derived fungus Fusarium equiseti SCSIO 41019. Chin. J. Antibiot. 2019, 44, 1035–1040.

- Wang, Q.X.; Li, S.F.; Zhao, F.; Dai, H.Q.; Bao, L.; Ding, R.; Gao, H.; Zhang, L.X.; Wen, H.A.; Liu, H.W. Chemical constituents from endophytic fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 777–781.

- Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Alhakamy, N.A.; Aljohani, O.S. Fusaroxazin, a novel cytotoxic and antimicrobial xanthone derivative from Fusarium oxysporum. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 952–960.

- Renner, M.K.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W. Neomangicols: Structures and absolute stereochemistries of unprecedented halogenated sesterterpenes from a marine fungus of the genus Fusarium. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 8346–8354.

- Li, S.; Shao, M.-W.; Lu, Y.-H.; Kong, L.-C.; Jiang, D.-H.; Zhang, Y.-L. Phytotoxic and antibacterial metabolites from Fusarium proliferatum ZS07 Isolated from the gut of long-horned grasshoppers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8997–9001.

- Jiang, C.X.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.M.; Jin, X.J.; Yu, B.; Fang, J.G.; Wu, Q.X. Isolation, identification, and activity evaluation of chemical constituents from soil fungus Fusarium avenaceum SF-1502 and endophytic fungus Fusarium proliferatum AF-04. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 1839–1846.

- Hussain, H.; Drogies, K.-H.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Hassan, Z.; Shah, A.; Rana, U.A.; Green, I.R.; Draeger, S.; Schulz, B.; Krohn, K. Antimicrobial constituents from endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2015, 5, 186–189.

- Lu, W.; Zhu, G.; Yuan, W.; Han, Z.; Dai, H.; Basiony, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Hsiang, T.; Zhang, J. Two novel aliphatic unsaturated alcohols isolated from a pathogenic fungus Fusarium proliferatum. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2021, 6, 446–451.

- Wen, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Ye, W.; Yao, X.; Che, Y. Fusagerins A-F, new alkaloids from the fungus Fusarium sp. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2015, 5, 195–203.

- Kılıç, G.; Tosun, G.; Bozdeveci, A.; Erik, İ.; Öztürk, E.; Reis, R.; Sipahi, H.; Cora, M.; Karaoğlu, Ş.A.; Yaylı, N. Antimicrobial, cytotoxic, antiviral wffects, and apectroscopic characterization of metabolites produced by fusarium oxysporum YP9B. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2021, 15, 547–567.

- Valla, A.; Giraud, M.; Labia, R.; Morand, A. In vitro inhibitory activity against bacteria of a fusarium mycotoxin and new synthetic derivatives. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1997, 6, 601–603.

- Kyekyeku, J.O.; Kusari, S.; Adosraku, R.K.; Bullach, A.; Golz, C.; Strohmann, C.; Spiteller, M. Antibacterial secondary metabolites from an endophytic fungus, Fusarium solani JK10. Fitoterapia 2017, 119, 108–114.

- Sibero, M.T.; Zhou, T.; Fukaya, K.; Urabe, D.; Radjasa, O.K.K.; Sabdono, A.; Trianto, A.; Igarashi, Y. Two new aromatic polyketides from a sponge-derived Fusarium. Beilstein. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 2941–2947.

- Tsuchinari, M.; Shimanuki, K.; Hiramatsu, F.; Murayama, T.; Koseki, T.; Shiono, Y. Fusapyridons A and B, novel pyridone alkaloids from an endophytic fungus, Fusarium sp. YG-45. Z. Naturforsch. B. 2007, 62, 1203–1207.

- Supratman, U.; Hirai, N.; Sato, S.; Watanabe, K.; Malik, A.; Annas, S.; Harneti, D.; Maharani, R.; Koseki, T.; Shiono, Y. New naphthoquinone derivatives from Fusarium napiforme of a mangrove plant. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 1406–1412.

- Khan, N.; Afroz, F.; Begum, M.N.; Roy Rony, S.; Sharmin, S.; Moni, F.; Mahmood Hasan, C.; Shaha, K.; Sohrab, M.H. Endophytic Fusarium solani: A rich source of cytotoxic and antimicrobial napthaquinone and aza-anthraquinone derivatives. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 970–976.

- Haraguchi, H.; Yokoyama, K.; Oike, S.; Ito, M.; Nozaki, H. Respiratory stimulation and generation of superoxide radicals in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by fungal naphthoquinones. Arch. Microbiol. 1997, 167, 6–10.

- Yan, C.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Deng, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, H. Bioactive terpenoids from Santalum album derived endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. YD-2. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 14823–14828.

- Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Xin, Z. Fusartricin, a sesquiterpenoid ether produced by an endophytic fungus Fusarium tricinctum Salicorn 19. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2014, 240, 805–814.

- Dong, J.W.; Cai, L.; Li, X.J.; Duan, R.T.; Shu, Y.; Chen, F.Y.; Wang, J.P.; Zhou, H.; Ding, Z.T. Production of a new tetracyclic triterpene sulfate metabolite sambacide by solid-state cultivated Fusarium sambucinum B10.2 using potato as substrate. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 218, 1266–1270.

- Shu, R.; Wang, F.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tan, R. Antibacterial and xanthine oxidase inhibitory cerebrosides from Fusarium sp. IFB-121, and endophytic fungus in Quercus variabilis. Lipids 2004, 39, 667–673.

- Sebastià, N.; Meca, G.; Soriano, J.M.; Mañes, J. Antibacterial effects of enniatins J(1) and J(3) on pathogenic and lactic acid bacteria. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 2710–2717.

- Chen, C.; Imamura, N.; Nishijima, M.; Adachi, K.; Sakai, M.; Sano, H. Halymecins, new antimicroalgal substances produced by fungi isolated from marine algae. J. Antibiot. 1996, 49, 998–1005.

- Shiono, Y.; Shibuya, F.; Murayama, T.; Koseki, T.; Poumale, H.M.P.; Ngadjui, B.T. A polyketide metabolite from an endophytic Fusarium equiseti in a medicinal plant. Z. Naturforsch. B. 2013, 68, 289–292.

- Ivanov, M.; Ćirić, A.; Stojković, D. Emerging antifungal targets and strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2756.

- Van Daele, R.; Spriet, I.; Wauters, J.; Maertens, J.; Mercier, T.; Van Hecke, S.; Brüggemann, R. Antifungal drugs: What brings the future? Med. Mycol. 2019, 57, S328–S343.

- Campoy, S.; Adrio, J.L. Antifungals. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 133, 86–96.

- Jackson, M.; Frost, D.J.; Karwowski, J.P.; Humphrey, P.E.; Dahod, S.K.; Choi, W.S.; Brandt, K.; Malmberg, L.-H.; Rasmussen, R.R.; Scherr, M.H. Fusacandins A and B; Novel Antifungal Antibiotics of the Papulacandin Class from Fusarium sambucinum I. Identity of the Producing Organism, Fermentation and Biological Activity. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48, 608–613.

- Chen, R.H.; Tennant, S.; Frost, D.; O’Beirne, M.J.; Karwowski, J.P.; Humphrey, P.E.; Malmberg, L.-H.; Choi, W.; Brandt, K.D.; West, P. Discovery of saricandin, a novel papulacandin, from a Fusarium species. J. Antibiot. 1996, 49, 596–598.

- Brady, S.F.; Clardy, J. CR377, a new pentaketide antifungal agent isolated from an endophytic fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1447–1448.

- Saetang, P.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Phongpaichit, S.; Sakayaroj, J.; Shi, X.; Chen, J.; Shen, X. β-Resorcylic macrolide and octahydronaphthalene derivatives from a seagrass-derived fungus Fusarium sp. PSU-ES123. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 6421–6427.

- Hiramatsu, F.; Miyajima, T.; Murayama, T.; Takahashi, K.; Koseki, T.; Shiono, Y. Isolation and structure elucidation of neofusapyrone from a marine-derived Fusarium species, and structural revision of fusapyrone and deoxyfusapyrone. J. Antibiot. 2006, 59, 704–709.

- Xu, X.; Zhao, S.; Yu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Shen, H.; Zhou, L. Beauvericin K, a new antifungal beauvericin analogue from a marine-derived Fusarium sp. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1825–1826.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Abdallah, H.M.; Elkhayat, E.S.; Al Musayeib, N.M.; Asfour, H.Z.; Zayed, M.F.; Mohamed, G.A. Fusaripeptide A: New antifungal and anti-malarial cyclodepsipeptide from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 20, 75–85.

- Dreyfuss, M.; Härri, E.; Hofmann, H.e.a.; Kobel, H.; Pache, W.; Tscherter, H. Cyclosporin A and C: New metabolites from Trichoderma polysporum (Link ex Pers.) Rifai. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 1976, 3, 125–133.

- Baráth, Z.; Baráthová, H.; Betina, V.; Nemec, P. Ramihyphins—Antifungal and morphogenic antibiotics from Fusarium sp. S-435. Folia. Microbiol. 1974, 19, 507–511.

- Parish, C.A.; Smith, S.K.; Calati, K.; Zink, D.; Wilson, K.; Roemer, T.; Jiang, B.; Xu, D.; Bills, G.; Platas, G. Isolation and structure elucidation of parnafungins, antifungal natural products that inhibit mRNA polyadenylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 7060–7066.

- Overy, D.; Calati, K.; Kahn, J.N.; Hsu, M.J.; Martin, J.; Collado, J.; Roemer, T.; Harris, G.; Parish, C.A. Isolation and structure elucidation of parnafungins C and D, isoxazolidinone-containing antifungal natural products. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 1224–1227.

- McBrien, K.D.; Gao, Q.; Huang, S.; Klohr, S.E.; Wang, R.R.; Pirnik, D.M.; Neddermann, K.M.; Bursuker, I.; Kadow, K.F.; Leet, J.E. Fusaricide, a new cytotoxic N-hydroxypyridone from Fusarium sp. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 1151–1153.

- Hilário, F.; Chapla, V.; Araujo, A.; Sano, P.; Bauab, T.; dos Santos, L. Antimicrobial Screening of Endophytic Fungi Isolated from the Aerial Parts of Paepalanthus chiquitensis (Eriocaulaceae) Led to the Isolation of Secondary Metabolites Produced by Fusarium fujikuroi. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2016, 28, 1389–1395.

- Ibrahim, S.M.; Mohamed, G.; Khayat, M.; Al Haidari, R.; El-Kholy, A.; Zayed, M. A new antifungal aminobenzamide derivative from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2019, 15, 204–207.

- Sakai, K.; Unten, Y.; Iwatsuki, M.; Matsuo, H.; Fukasawa, W.; Hirose, T.; Chinen, T.; Nonaka, K.; Nakashima, T.; Sunazuka, T.; et al. Fusaramin, an antimitochondrial compound produced by Fusarium sp., discovered using multidrug-sensitive Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Antibiot. 2019, 72, 645–652.

- Woscholski, R.; Kodaki, T.; McKinnon, M.; Waterfield, M.D.; Parker, P.J. A comparison of demethoxyviridin and wortmannin as inhibitors of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. FEBS Lett. 1994, 342, 109–114.

- Pedersen, P.B.; Miller, J.D. The fungal metabolite culmorin and related compounds. Nat. Toxins 1999, 7, 305–309.

- Strongman, D.; Miller, J.; Calhoun, L.; Findlay, J.; Whitney, N. The biochemical basis for interference competition among some lignicolous marine fungi. Bot. Mar. 1987, 30, 21–26.

- Kurobane, I.; Zaita, N.; Fukuda, A. New metabolites of Fusarium martii related to dihydrofusarubin. J. Antibiot. 1986, 39, 205–214.

- Limón, M.C.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, R.; Avalos, J. Bikaverin production and applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 21–29.

- Deshmukh, R.; Mathew, A.; Purohit, H.J. Characterization of antibacterial activity of bikaverin from Fusarium sp. HKF15. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2014, 117, 443–448.

- Bushnell, G.W.; Li, Y.-L.; Poulton, G.A. Pyrones. X. Lateropyrone, a new antibiotic from the fungus Fusarium lateritium Nees. Can. J. Chem. 1984, 62, 2101–2106.

- Clark, T.N.; Carroll, M.; Ellsworth, K.; Guerrette, R.; Robichaud, G.A.; Johnson, J.A.; Gray, C.A. Antibiotic mycotoxins from an endophytic Fusarium acuminatum isolated from the medicinal plant Geum macrophyllum. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1934578X1801301017.

- Ariantari, N.P.; Frank, M.; Gao, Y.; Stuhldreier, F.; Kiffe-Delf, A.-L.; Hartmann, R.; Höfert, S.-P.; Janiak, C.; Wesselborg, S.; Müller, W.E.G.; et al. Fusaristatins D–F and (7S,8R)-(−)-chlamydospordiol from Fusarium sp. BZCB-CA, an endophyte of Bothriospermum chinense. Tetrahedron 2021, 85, 132065–132071.

- Ola, A.R.B.; Thomy, D.; Lai, D.; Brötz-Oesterhelt, H.; Proksch, P. Inducing secondary metabolite production by the endophytic fungus Fusarium tricinctum through coculture with Bacillus subtilis. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 2094–2099.

- Okada, H.; Nagashima, M.; Suzuki, H.; Nakajima, S.; Kojiri, K.; Suda, H. BE-29602, a new member of the papulacandin family. J. Antibiot. 1996, 49, 103–106.

- Kobayashi, H.; Sunaga, R.; Furihata, K.; Morisaki, N.; IWasaki, S. Isolation and structures of an antifungal antibiotic, fusarielin A, and related compounds produced by a Fusarium sp. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48, 42–52.

- Liang, X.A.; Ma, Y.M.; Zhang, H.C.; Liu, R. A new helvolic acid derivative from an endophytic Fusarium sp. of Ficus carica. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 2407–2412.

- Janevska, S.; Arndt, B.; Niehaus, E.-M.; Burkhardt, I.; Rösler, S.M.; Brock, N.L.; Humpf, H.-U.; Dickschat, J.S.; Tudzynski, B. Gibepyrone biosynthesis in the rice pathogen Fusarium fujikuroi is facilitated by a small polyketide synthase gene cluster. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 27403–27420.

- Zhou, G.; Qiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, C.; Che, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, T.; Gu, Q.; Li, D. Fusaricates H-K and fusolanones A-B from a mangrove endophytic fungus Fusarium solani HDN15-410. Phytochemistry 2019, 158, 13–19.

- Evidente, A.; Conti, L.; Altomare, C.; Bottalico, A.; Sindona, G.; Segre, A.L.; Logrieco, A. Fusapyrone and deoxyfusapyrone, two antifungal α-pyrones from Fusarium semitectum. Nat. Toxins 1994, 2, 4–13.

- Altomare, C.; Perrone, G.; Zonno, M.C.; Evidente, A.; Pengue, R.; Fanti, F.; Polonelli, L. Biological characterization of fusapyrone and deoxyfusapyrone, two bioactive secondary metabolites of Fusarium semitectum. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1131–1135.

- Son, S.; Kim, H.; Choi, G.; Lim, H.; Jang, K.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Sung, N.; Kim, J.C. Bikaverin and fusaric acid from Fusarium oxysporum show antioomycete activity against Phytophthora infestans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 692–698.

- Bacon, C.W.; Hinton, D.M.; Hinton, A., Jr. Growth-inhibiting effects of concentrations of fusaric acid on the growth of Bacillus mojavensis and other biocontrol Bacillus species. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 100, 185–194.

- Poleto, L.; da Rosa, L.O.; Fontana, R.C.; Rodrigues, E.; Poletto, E.; Baldo, G.; Paesi, S.; Sales-Campos, C.; Camassola, M. Production of antimicrobial metabolites against pathogenic bacteria and yeasts by Fusarium oxysporum in submerged culture processes. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 44, 1321–1332.

- Vesonder, R.F.; Tjarks, L.W.; Rohwedder, W.K.; Burmeister, H.R.; Laugal, J.A. Equisetin, an antibiotic from Fusarium equisetin NRRL 5537, identified as a derivative of N-methyl-2, 4-pyrollidone. J. Antibiot. 1979, 32, 759–761.

- Ratnaweera, P.B.; de Silva, E.D.; Williams, D.E.; Andersen, R.J. Antimicrobial activities of endophytic fungi obtained from the arid zone invasive plant Opuntia dillenii and the isolation of equisetin, from endophytic Fusarium sp. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 220.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Elkhayat, E.S.; Mohamed, G.A.A.; Fat’hi, S.M.; Ross, S.A. Fusarithioamide A, a new antimicrobial and cytotoxic benzamide derivative from the endophytic fungus Fusarium chlamydosporium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 479, 211–216.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Al Haidari, R.A.; Zayed, M.F.; El-Kholy, A.A.; Elkhayat, E.S.; Ross, S.A. Fusarithioamide B, a new benzamide derivative from the endophytic fungus Fusarium chlamydosporium with potent cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 786–790.

- Jiang, Z.; Barret, M.-O.; Boyd, K.G.; Adams, D.R.; Boyd, A.S.; Burgess, J.G. JM47, a cyclic tetrapeptide HC-toxin analogue from a marine Fusarium species. Phytochemistry 2002, 60, 33–38.

- Roig, M.; Meca, G.; Marin, R.; Ferrer, E.; Manes, J. Antibacterial activity of the emerging Fusarium mycotoxins enniatins A, A(1), A(2), B, B(1), and B(4) on probiotic microorganisms. Toxicon 2014, 85, 1–4.

- Meca, G.; Sospedra, I.; Valero, M.A.; Manes, J.; Font, G.; Ruiz, M.J. Antibacterial activity of the enniatin B, produced by Fusarium tricinctum in liquid culture, and cytotoxic effects on Caco-2 cells. Toxicol. Mech. Method. 2011, 21, 503–512.

- Meca, G.; Soriano, J.M.; Gaspari, A.; Ritieni, A.; Moretti, A.; Manes, J. Antifungal effects of the bioactive compounds enniatins A, A(1), B, B(1). Toxicon 2010, 56, 480–485.

- Tsantrizos, Y.S.; Xu, X.-J.; Sauriol, F.; Hynes, R.C. Novel quinazolinones and enniatins from Fusarium lateritium Nees. Can. J. Chem. 1993, 71, 1362–1367.

- Meca, G.; Sospedra, I.; Soriano, J.M.; Ritieni, A.; Moretti, A.; Manes, J. Antibacterial effect of the bioactive compound beauvericin produced by Fusarium proliferatum on solid medium of wheat. Toxicon 2010, 56, 349–354.

- Wu, Q.; Patocka, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K. A Review on the Synthesis and Bioactivity Aspects of Beauvericin, a Fusarium Mycotoxin. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1338.

- Hawas, U.W.; Al-Farawati, R.; Abou El-Kassem, L.T.; Turki, A.J. Different Culture Metabolites of the Red Sea Fungus Fusarium equiseti Optimize the Inhibition of Hepatitis C Virus NS3/4A Protease (HCV PR). Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 190.

- Tompa, D.R.; Immanuel, A.; Srikanth, S.; Kadhirvel, S. Trends and strategies to combat viral infections: A review on FDA approved antiviral drugs. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 172, 524–541.

- Chang, S.; Yan, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, W.; Gao, R.; Li, Y.; Yu, L.; Xie, Y.; Si, S.; Chen, M. Cytotoxic hexadepsipeptides and anti-coronaviral 4-hydroxy-2-pyridones from an endophytic Fusarium sp. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1106869.

- McKee, T.C.; Bokesch, H.R.; McCormick, J.L.; Rashid, M.A.; Spielvogel, D.; Gustafson, K.R.; Alavanja, M.M.; Cardelline, J.H., 2nd; Boyd, M.R. Isolation and characterization of new anti-HIV and cytotoxic leads from plants, marine, and microbial organisms. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 431–438.

- Guo, Y.W.; Liu, X.J.; Yuan, J.; Li, H.J.; Mahmud, T.; Hong, M.J.; Yu, J.C.; Lan, W.J. l-Tryptophan induces a marine-derived Fusarium sp. to produce indole alkaloids with activity against the Zika virus. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 3372–3380.

- Nonaka, K.; Chiba, T.; Suga, T.; Asami, Y.; Iwatsuki, M.; Masuma, R.; Ōmura, S.; Shiomi, K. Coculnol, a new penicillic acid produced by a coculture of Fusarium solani FKI-6853 and Talaromyces sp. FKA-65. J. Antibiot. 2015, 68, 530–532.

- Lee, S.M.; Kim, M.S.; Hayat, F.; Shin, D. Recent Advances in the Discovery of Novel Antiprotozoal Agents. Molecules 2019, 24, 3386.

- Trisuwan, K.; Khamthong, N.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Phongpaichit, S.; Preedanon, S.; Sakayaroj, J. Anthraquinone, cyclopentanone, and naphthoquinone derivatives from the sea fan-derived fungi Fusarium spp. PSU-F14 and PSU-F135. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1507–1511.

- Balan, J.; Fuska, J.; Kuhr, I.; Kuhrová, V. Bikaverin, an antibiotic from Gibberella fujikuroi, effective against Leishmania brasiliensis. Folia Microbiol. 1970, 15, 479–484.

- Nascimento, A.M.d.; Conti, R.; Turatti, I.C.; Cavalcanti, B.C.; Costa-Lotufo, L.V.; Pessoa, C.; Moraes, M.O.d.; Manfrim, V.; Toledo, J.S.; Cruz, A.K. Bioactive extracts and chemical constituents of two endophytic strains of Fusarium oxysporum. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2012, 22, 1276–1281.

- Campos, F.F.; Sales Junior, P.A.; Romanha, A.J.; Araújo, M.S.; Siqueira, E.P.; Resende, J.M.; Alves, T.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Santos, V.L.d.; Rosa, C.A. Bioactive endophytic fungi isolated from Caesalpinia echinata Lam. (Brazilwood) and identification of beauvericin as a trypanocidal metabolite from Fusarium sp. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2015, 110, 65–74.

- Ibrahim, S.R.; Abdallah, H.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ross, S.A. Integracides H-J: New tetracyclic triterpenoids from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. Fitoterapia 2016, 112, 161–167.

- Abdelhakim, I.; Bin Mahmud, F.; Motoyama, T.; Futamura, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Osada, H. Dihydrolucilactaene, a potent antimalarial compound from Fusarium sp. RK97-94. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 85, 63–69.

- Kato, S.; Motoyama, T.; Futamura, Y.; Uramoto, M.; Nogawa, T.; Hayashi, T.; Hirota, H.; Tanaka, A.; Takahashi-Ando, N.; Kamakura, T. Biosynthetic gene cluster identification and biological activity of lucilactaene from Fusarium sp. RK97-94. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 84, 1303–1307.

- Abdelhakim, I.A.; Motoyama, T.; Nogawa, T.; Mahmud, F.B.; Futamura, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Osada, H. Isolation of new lucilactaene derivatives from P450 monooxygenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase knockout Fusarium sp. RK97-94 strains and their biological activities. J. Antibiot. 2022, 75, 361–374.

- Singh, S.B.; Zink, D.L.; Polishook, J.D.; Dombrowski, A.W.; Darkin-Rattray, S.J.; Schmatz, D.M.; Goetz, M.A. Apicidins: Novel cyclic tetrapeptides as coccidiostats and antimalarial agents from Fusarium pallidoroseum. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 8077–8080.

- Singh, S.B.; Zink, D.L.; Liesch, J.M.; Dombrowski, A.W.; Darkin-Rattray, S.J.; Schmatz, D.M.; Goetz, M.A. Structure, histone deacetylase, and antiprotozoal activities of apicidins B and C, congeners of apicidin with proline and valine substitutions. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 2815–2818.

- Von Bargen, K.W.; Niehaus, E.-M.; Bergander, K.; Brun, R.; Tudzynski, B.; Humpf, H.-U. Structure elucidation and antimalarial activity of apicidin F: An apicidin-like compound produced by Fusarium fujikuroi. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 2136–2140.

More

Information

Subjects:

Pharmacology & Pharmacy

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

627

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Apr 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No