| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rosa María Funes Moñux | -- | 1932 | 2023-04-13 07:26:31 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1932 | 2023-04-13 08:14:55 | | |

Video Upload Options

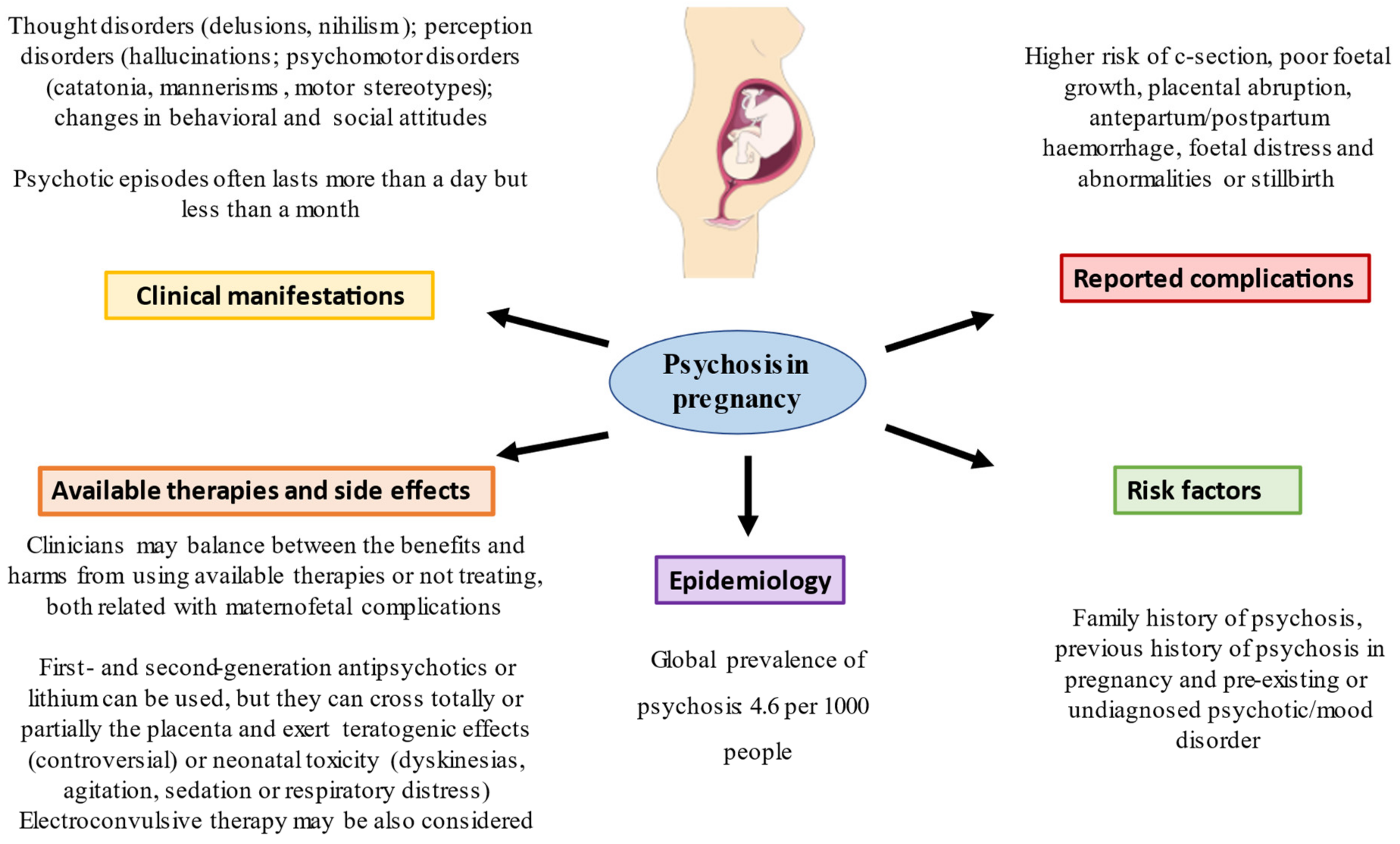

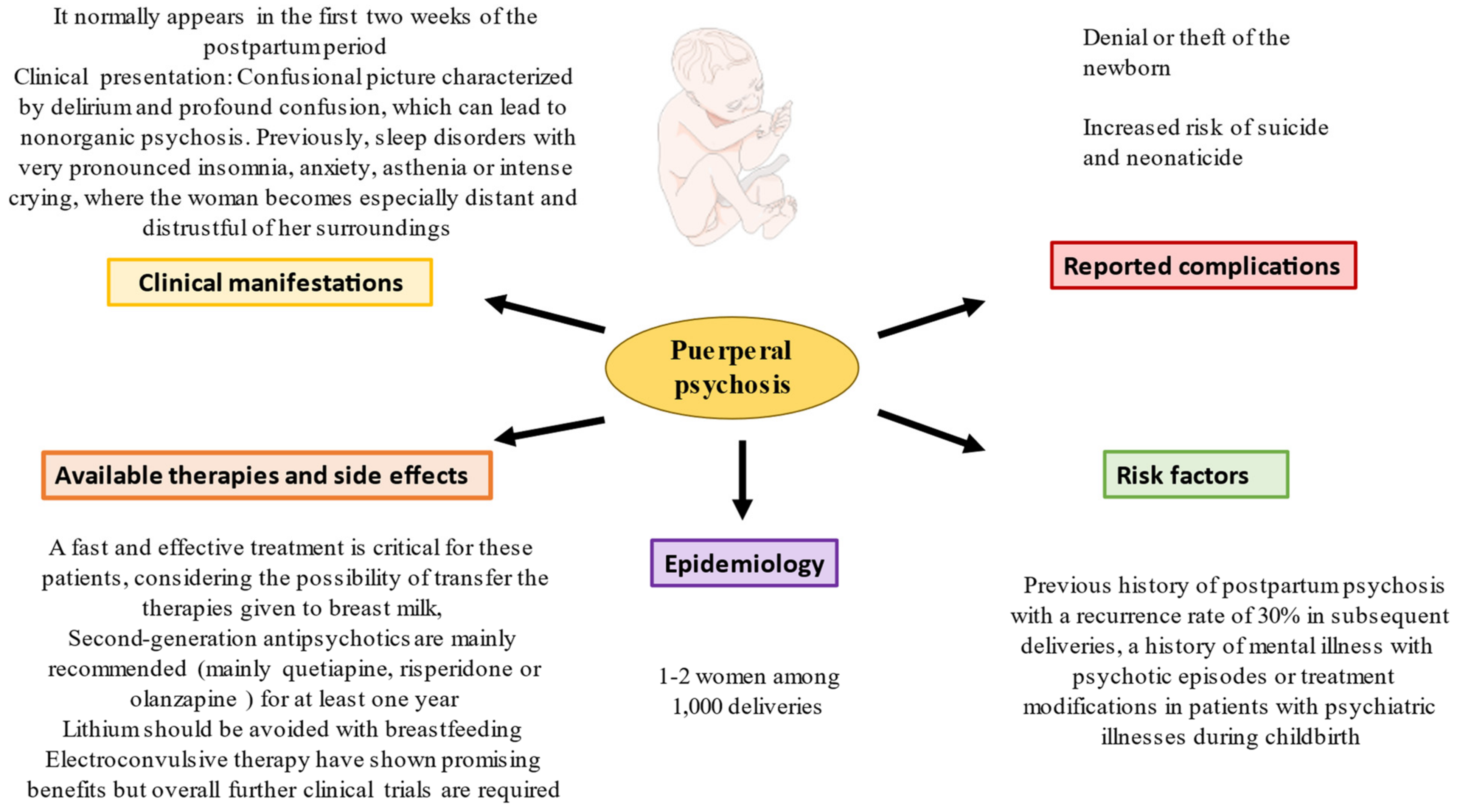

Psychotic episodes represent one of the most complex manifestations of various mental illnesses, and these encompass a wide variety of clinical manifestations that together lead to high morbidity in the general population. Various mental illnesses are associated with psychotic episodes; in addition, their incidence and prevalence rates have been widely described in the general population, their correct identification and treatment is a challenge for health professionals in relation to pregnancy. In pregnant women, psychotic episodes can be the consequence of the manifestation of a previous psychiatric illness or may begin during the pregnancy itself, placing not only the mother, but also the fetus at risk during the psychotic episode.

1. Introduction and Psychosis during Pregnancy

2. Treatment of Psychotic Episodes during Pregnancy

3. Puerperal Psychosis Treatment

References

- Heckers, S.; Barch, D.M.; Bustillo, J.; Gaebel, W.; Gur, R.; Malaspina, D.; Owen, M.J.; Schultz, S.; Tandon, R.; Tsuang, M.; et al. Structure of the psychotic disorders classification in DSM-5. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 150, 11–14.

- Moreno-Küstner, B.; Martín, C.; Pastor, L. Prevalence of psychotic disorders and its association with methodological issues. A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195687.

- Salud_Mental_Datos. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/SIAP/Salud_mental_datos.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Sharma, I.; Rai, S.; Pathak, A. Postpartum psychiatric disorders: Early diagnosis and management. Indian J. Psychiatry 2015, 57, S216.

- Zhong, Q.-Y.; Gelaye, B.; Fricchione, G.L.; Avillach, P.; Karlson, E.W.; Williams, M.A. Adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes complicated by psychosis among pregnant women in the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 120.

- Watkins, M.E.; Newport, D.J. Psychosis in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 113, 1349–1353.

- MacCabe, J.H.; Martinsson, L.; Lichtenstein, P.; Nilsson, E.; Cnattingius, S.; Murray, R.; Hultman, C.M. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in mothers with affective psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2007, 9, 305–309.

- Calabrese, J.; Al Khalili, Y. Psychosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546579/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Grace, A.A. Pathophysiology of psychosis and novel approaches to treatment. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 28, e12.

- Toh, S.; Li, Q.; Cheetham, T.C.; Cooper, W.O.; Davis, R.L.; Dublin, S.; Hammad, T.A.; Li, D.-K.; Pawloski, P.; Pinheiro, S.P.; et al. Prevalence and trends in the use of antipsychotic medications during pregnancy in the U.S.; 2001–2007: A population-based study of 585,615 deliveries. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2013, 16, 149–157.

- Altshuler, L.L.; Cohen, L.; Szuba, M.P.; Burt, V.K.; Gitlin, M.; Mintz, J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: Dilemmas and guidelines. Am. J. Psychiatry 1996, 153, 592–606.

- McKenna, K.; Koren, G.; Tetelbaum, M.; Wilton, L.; Shakir, S.; Diav-Citrin, O.; Levinson, A.; Zipursky, R.B.; Einarson, A. Pregnancy Outcome of Women Using Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2005, 66, 444–449.

- Huybrechts, K.F.; Hernández-Díaz, S.; Patorno, E.; Desai, R.J.; Mogun, H.; Dejene, S.Z.; Cohen, J.; Panchaud, A.; Cohen, L.; Bateman, B.T. Antipsychotic Use in Pregnancy and the Risk for Congenital Malformations. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 938–946.

- Newport, D.J.; Calamaras, M.R.; DeVane, C.L.; Donovan, J.; Beach, A.J.; Winn, S.; Knight, B.T.; Gibson, B.B.; Viguera, A.C.; Owens, M.J.; et al. Atypical Antipsychotic Administration During Late Pregnancy: Placental Passage and Obstetrical Outcomes. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 1214–1220.

- Weinstein, M.R.; Goldfield, M. Cardiovascular malformations with lithium use during pregnancy. Am. J. Psychiatry 1975, 132, 529–531.

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Sharma, V.; McIntyre, R.S. Teratogenesis associated with antibipolar agents. Adv. Ther. 2009, 26, 281–294.

- Menon, S.J. Psychotropic medication during pregnancy and lactation. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2007, 277, 1–13.

- Cipriani, A.; Barbui, C.; Salanti, G.; Rendell, J.; Brown, R.; Stockton, S.; Purgato, M.; Spineli, L.M.; Goodwin, G.M.; Geddes, J.R. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: A multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2011, 378, 1306–1315.

- Ortega, M.A.; Fraile-Martinez, O.; García-Montero, C.; Rodriguez-Martín, S.; Funes Moñux, R.M.; Bravo, C.; De Leon-Luis, J.A.; Saz, J.V.; Saez, M.A.; Guijarro, L.G.; et al. Evidence of Increased Oxidative Stress in the Placental Tissue of Women Who Suffered an Episode of Psychosis during Pregnancy. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 179.

- Overview|Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: Clinical Management and Service Guidance|Guidance|NICE. NICE|The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Perugi, G.; Medda, P.; Toni, C.; Mariani, M.G.; Socci, C.; Mauri, M. The Role of Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) in Bipolar Disorder: Effectiveness in 522 Patients with Bipolar Depression, Mixed-state, Mania and Catatonic Features. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 359–371.

- Bergink, V.; Burgerhout, K.M.; Koorengevel, K.M.; Kamperman, A.M.; Hoogendijk, W.J.; Berg, M.P.L.-V.D.; Kushner, S.A. Treatment of Psychosis and Mania in the Postpartum Period. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 115–123.

- Leucht, S.; Corves, C.; Arbter, D.; Engel, R.R.; Li, C.; Davis, J.M. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Lancet 2009, 373, 31–41.

- Carbon, M.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Kane, J.M.; Correll, C.U. Tardive Dyskinesia Prevalence in the Period of Second-Generation Antipsychotic Use. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78, e264–e278.

- Eberhard-Gran, M.; Eskild, A.; Opjordsmoen, S. Use of Psychotropic Medications in Treating Mood Disorders during Lactation. CNS Drugs 2006, 20, 187–198.

- Alvarez-Mon, M.A.; Gómez-Lahoz, A.M.; Orozco, A.; Lahera, G.; Diaz, D.; Ortega, M.A.; Albillos, A.; Quintero, J.; Aubá, E.; Monserrat, J.; et al. Expansion of CD4 T Lymphocytes Expressing Interleukin 17 and Tumor Necrosis Factor in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 220.

- Birnbaum, C.S.; Cohen, L.S.; Bailey, J.W.; Grush, L.R.; Robertson, L.M.; Stowe, Z.N. Serum Concentrations of Antidepressants and Benzodiazepines in Nursing Infants: A Case Series. Pediatrics 1999, 104, e11.

- Sani, G.; Perugi, G.; Tondo, L. Treatment of Bipolar Disorder in a Lifetime Perspective: Is Lithium Still the Best Choice? Clin. Drug Investig. 2017, 37, 713–727.

- Bergink, V.; Rasgon, N.; Wisner, K.L. Postpartum Psychosis: Madness, Mania, and Melancholia in Motherhood. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 1179–1188.

- Reed, P.; Sermin, N.; Appleby, L.; Faragher, B. A comparison of clinical response to electroconvulsive therapy in puerperal and non-puerperal psychoses. J. Affect. Disord. 1999, 54, 226–255.

- Rundgren, S.; Brus, O.; Båve, U.; Landén, M.; Lundberg, J.; Nordanskog, P.; Nordenskjöld, A. Improvement of postpartum depression and psychosis after electroconvulsive therapy: A population-based study with a matched comparison group. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 235, 258–264.

- Jones, I.; Smith, S. Puerperal psychosis: Identifying and caring for women at risk. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2009, 15, 411–418.