Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carla Lucia Esposito | -- | 4098 | 2023-04-06 05:33:53 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -3 word(s) | 4095 | 2023-04-06 05:38:47 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ciccone, G.; Ibba, M.L.; Coppola, G.; Catuogno, S.; Esposito, C.L. Small RNA Landscape in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42830 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Ciccone G, Ibba ML, Coppola G, Catuogno S, Esposito CL. Small RNA Landscape in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42830. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Ciccone, Giuseppe, Maria Luigia Ibba, Gabriele Coppola, Silvia Catuogno, Carla Lucia Esposito. "Small RNA Landscape in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42830 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Ciccone, G., Ibba, M.L., Coppola, G., Catuogno, S., & Esposito, C.L. (2023, April 06). Small RNA Landscape in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42830

Ciccone, Giuseppe, et al. "Small RNA Landscape in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer." Encyclopedia. Web. 06 April, 2023.

Copy Citation

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the second most diagnosed type of malignancy and the first cause of cancer death worldwide. The treatment of choice for NSCLC patients remains to be chemotherapy, often showing very limited effectiveness with the frequent occurrence of drug-resistant phenotype and the lack of selectivity for tumor cells. Therefore, new effective and targeted therapeutics are needed. Short RNA-based therapeutics, including Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs), microRNAs (miRNAs), short interfering (siRNA) and aptamers, represent a promising class of molecules.

NSCLC

aptamer

ASO

RNAi

1. Introduction

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents the majority of LC covering about 80–85% of all cases. It includes adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and large-cell carcinoma subtypes. NSCLC is the most common cancer worldwide and a leading cause of cancer death, with more than 1.6 million deaths each year, according to the World Health Organization [1].

The main therapeutic approaches for NSCLC treatment include surgery, chemotherapy with platinum-based compounds and/or radiotherapy. In addition, for some subgroups of patients with advanced NSCLC, targeted therapies with Tyrosine Kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immunotherapies with anti-Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD–L1) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are frequently used. Despite advances, the 5-year relative survival rate for NSCLC patients is about 26%, and the resistance to therapies and relapses are very recurrent [2]. Therefore, the development of new targeted therapies and strategies for restoring patients’ responsiveness to common drugs is essential.

There is a growing interest in small RNA-based therapeutics including Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs), microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs), short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and aptamers. ASOs, miRNAs and siRNAs act by targeting and inhibiting specific target mRNAs, whereas aptamers are 3D-structured oligonucleotides serving as high-affinity ligands and potential antagonists of disease-associated proteins (Figure 1).

Figure 1. RNA-based therapeutics general mechanism of action. Scheme of the main mechanism of action of small RNA-based therapeutics: ASOs, miRNAs, and siRNAs bind to mRNA preventing proteins translation; aptamers bind their target protein by folding into complex tridimensional shapes.

In addition, more recently, small double-strand RNAs (dsRNAs), able to activate endogenous genes by a mechanism of a gene promoter targeting involving epigenetic modifications, have been described and termed small activating RNAs (saRNAs). This new class of small RNAs shows great potential; however, their application to NSCLC has been very limited so far [3].

Small RNA-based therapeutics offer exquisite advantages for therapeutic purposes in terms of flexibility, low toxicity and target-specificity, and permit researchers to reach non-druggable targets. Further, the introduction of several chemical modifications has been permitted to highly increase the RNA stability and improve their lack of immunogenicity [4][5][6]. Nevertheless, the efficacy is limited by: (1) the reduced RNA permeability limiting the crossing through the human body barriers; (2) the necessity to develop tissue-specific delivery strategies to allow drug accumulation in diseased sites avoiding the occurrence of off-target effects. Therefore, several delivery tools have been developed to improve barrier penetrance and intracellular uptake, including nanoparticles (NPs). NPs offer interesting and versatile carriers [7], but they generally show a preferential accumulation into the liver and require decoration with targeting ligands for a cell-specific delivery. To address cell-specific targeting, natural or artificial ligands have been explored. Among natural carriers, widely used is the N-acetyl-galactosamine (GalNAc) ligand recognized by the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGP) that is present on the hepatocyte surface and allows liver targeting [8]. Other natural ligands used as cell-specific carriers comprise transferrin [9] and small molecules, such as folate [10][11], employed for the targeting of the brain and other cancers (including NSCLC), respectively. In addition, artificial ligands, such as antibodies, proteins, peptides and aptamers, able to recognize cell surface receptors and permit cell-specific internalization, have been used for the targeted delivery. Among them, aptamers hold many useful features including good tumor penetration, cost-effectiveness, no toxicity, no immunogenicity and easy modification to improve their pharmacokinetic profile [12].

2. Therapeutic RNA Stability and Immunogenicity

A major hurdle for the therapeutic use of RNAs is represented by their instability due to the susceptibility to enzymatic degradation. To overcome this limitation, different chemical modifications to enhance RNA resistance to nucleases have been proposed. Substitutions at the 2′-position of the ribose have been frequently employed to address this issue. These include the introduction of 2′-fluoro, 2′-amino or 2′-O-metyl groups or the use of locked nucleic acids (LNAs) that contain a methylene bridge between the 2′-O to the 4′-C of the sugar. Modifications of the phosphate group, as the inclusion of phosphorothioates, or the capping at the 3′-terminus have been applied to improve RNA resistance to degradation, as well [13]. In addition to the improvement of the resistance, the use of alternative bases (e.g., pseu-douridines) has been found to ameliorate the stability of the duplex structures, enhanc-ing the functional activity of dsRNA molecules [14].

Importantly, chemical modifications of RNAs also improve their immunogenic profile. Different pathways, including Toll-like receptor (TLR) 3, 7 and 8, dsR-NA-dependent protein kinase (PKR), retinoid-acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and/or melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA-5) pathways, physiologically recognize RNA molecules inducing innate immune response with the production of interferon (IFN) and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Small synthetic RNAs can be recognized by these systems and activate innate immunity [15], but this can be easily prevented through the design of non-immunogenic molecules avoiding the presence of immune-stimulatory motifs [16][17] and introducing modified nucleotides [18]. Concerning NSCLC, toxicology studies in rodents and primates have been performed for different small RNAs that are in clinical trials, revealing no controllable immune response activation [19][20][21]. However, the majority of therapeutically relevant RNA molecules proposed for NSCLC are still at an early preclinical phase of investigation and there are currently data on their effects on the host immune system in immunocompetent models available. Regarding the immunostimulatory properties of some small RNAs (mainly siRNAs and miRNAs), it should be considered that in some specific circumstances, the activation of the immune system represents a remedy for therapy, and the design of new RNA-based agents stimulating the host immune system has been explored for cancer and viral infection treatment [22].

3. ASOs

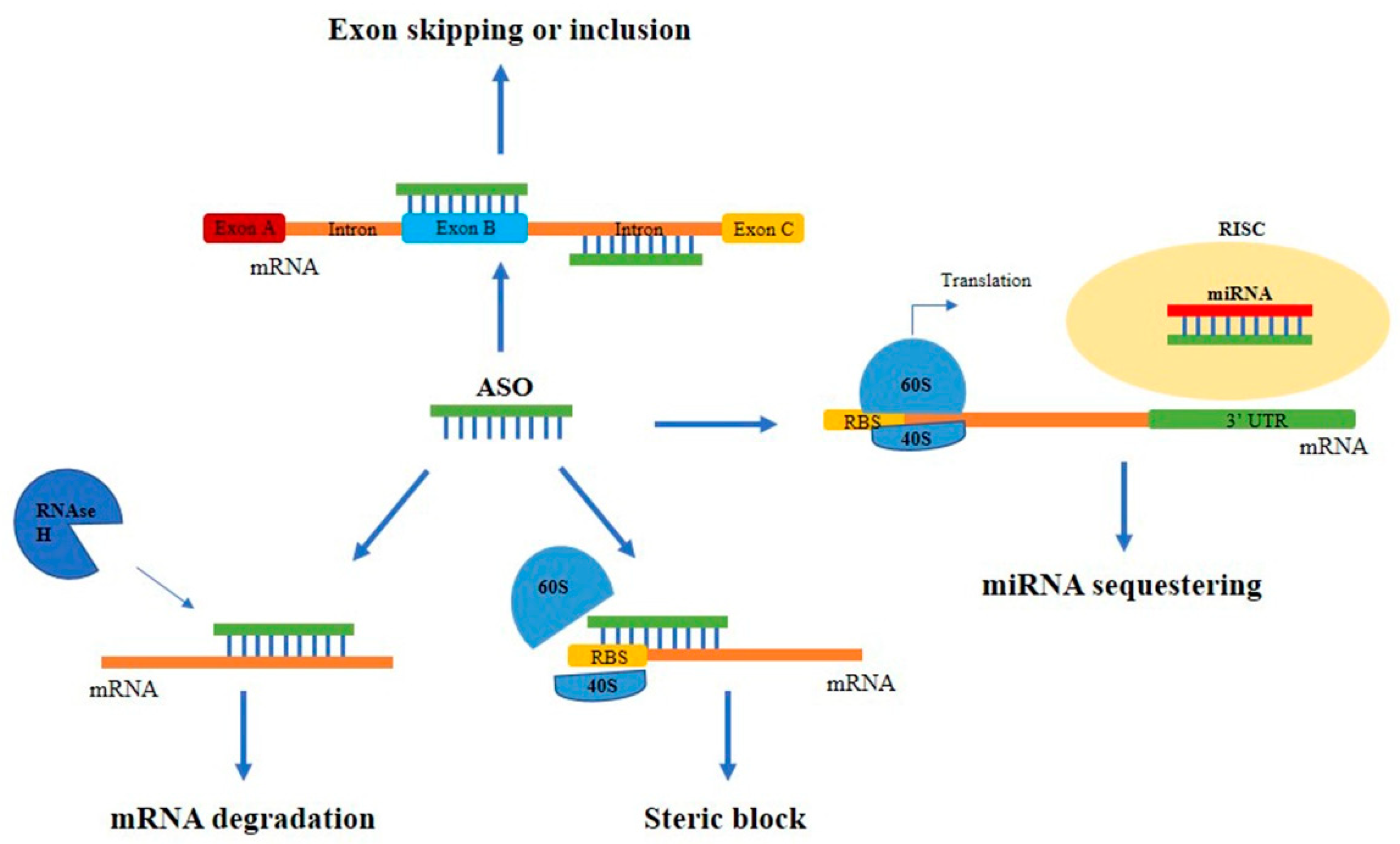

Antisense oligonucleotide-based therapy is a captivating approach to cancer treatment. ASOs are small (18-20 nucleotides) single-stranded modified oligonucleotides capable of hybridizing specific target mRNAs through base pairing recognition. The main mechanism of action of ASOs is the formation of hetero-duplexes with the mRNA in the cytoplasm, leading to the activation of the ubiquitous endonuclease RNase H and the hydrolysis of the complexes or to the alteration of the correct ribosomal assembly. Alternatively, ASOs can act by entering the nucleus and regulating mRNA maturation through the inhibition of the 5′ cap formation, of the normal splicing, or through the activation of the RNase H [23][24][25][26] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Main mechanisms of action of ASOs. Schematic representation of the different mechanisms of action of ASOs. ASOs can block protein expression by binding to the mRNA and leading to: (i) the RNase H-mediated mRNA degradation; (ii) the steric block of the correct ribosomal assembly; (iii) the alteration of the normal splicing causing exon skipping or inclusion. Alternatively, they can sequestrate miRNAs avoiding their binding to target mRNAs.

ASOs activating RNase H have generally a specific composition with a central region of minimum of five DNA nucleotides called ‘gapmer’, flanked by RNA sequences, which increase the binding to the target. Steric block ASOs, instead, do not contain the DNA strand core, but include mixed modified nucleotides, such as LNAs, morpholinos, peptide nucleic acids and thiophosphoroamidates [27].

Antisense strategies have been used for decades with the purpose of downregulating over-expressed genes, but more recently have been employed even in the opposite situation, where the upregulation of therapeutic proteins could lead to a beneficial effect. This new approach is allowed by the development of new ASOs targeting miRNAs (called anti-miRNAs) that avoid miR binding to target mRNAs with a consequent upregulation of the translation. In addition, ASOs could be designed to target the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNAs, which is often responsible for translational repression mainly through the formation of stem-loop structures [28].

Currently, ASOs are among the most advanced small RNA therapeutics in clinical trials, with several molecules approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of different disorders. Among approved ASOs, there are: Fomivirsen for cytomegalovirus retinitis; Mipomersen for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia; Eteplirsen and Golodirsen for Duchenne muscular dystrophy; Nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy; Inotersen and Patisiran for polyneuropathy caused by hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis; Givosiran for acute hepatic porphyria; and Milasen, for neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis 7 [29].

ASOs have been widely applied to NSCLC therapy by targeting key genes regulators of the malignant phenotype, such as B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2), Protein Kinase B (PKB/Akt-1), Kirsten Rat Sarcoma virus (KRAS), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3), clusterin and Protein Kinase C alpha (PKC alpha).

KRAS is one of the most mutated genes in different human cancers, including NSCLC [30]. It is considered a good target for anti-cancer therapies and many KRAS inhibitors are currently under evaluation in clinical trials [31]. AZD4785 is an ASO containing 2′-4′ constrained ethyl residues (cEt). It targets mutated KRAS mRNA with high affinity and is able to induce its degradation. This ASO blocks pathways activated by KRAS hampering the proliferation of KRAS-mutated cancer cells [32]. Ross SJ et al. tested the efficacy of AZD4785 in multiple xenograft mouse models of NSCLC, demonstrating a good anti-tumor effect upon its systemic injection. In addition, they demonstrated ASO safety in primates, paving the way for the experimentation of its efficacy in a phase 1 clinical trial [32]. More recently, Wang et al. [33] reported a novel anti-KRAS ASO with improved antisense activity and pharmacokinetics. They designed a bottlebrush-like complex consisting of a DNA backbone, poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) side chains and ASO overhanging. In this construct, PEG protects the ASO from enzymatic degradation, while ASO overhangs increase the chance of hybridization with the target. By using NSCLC cell models, authors showed that this molecule allows a higher antisense efficacy than unassembled hairpins and displays an improved retention time in vivo [33].

The over-expression of Bcl2 and its activator Akt-1 is responsible for the increased cancer cell viability, growth and apoptotic evasion in NSCLC [34][35]. Specific gapmer-based ASOs, called G3139 and RX-020, have been devised against Bcl2 and Akt-1 mRNAs, respectively, and tested in pre-clinical and clinical studies for NSCLC therapy. However, they did not reach success in clinical trials due to improper delivery. In order to improve ASO effectiveness, G3139 and RX-020 have been modified at the 5′ and the 3′ ends with 2′-O-methyl groups, and loaded in lipid NPs [36]. ASO-NP complexes demonstrated excellent cellular uptake and colloidal stability that let them gain a better anti-tumor effect in xenograft mouse models. Moreover, G3139 has been also incorporated in DOTAP/egg PC/cholesterol/Tween 80 lipid NPs and tested both in vitro and in vivo in NSCLC models. This complex gives an effective reduction in Bcl2 protein level and cell growth inhibition [37].

In order to target STAT3, a key transcription factor over-expressed in NSCLC, an ethyl-modified ASO, called AZD9150, has been designed by Hong D et al. and tested in vitro in multiple cell lines [19]. The ASO was 10–20 times more potent than the earlier generation (Gen 2.0) STAT3 ASOs, showing half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for the most sensitive cells in the nanomolar range. Next, AZD9150 gave a strong inhibition of STAT3 in human primary patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of NSCLC, colorectal cancer and lymphoma. Most importantly, the authors described a phase I dose-escalation study where AZD9150 antitumor activity as a single agent was observed in patients with highly treatment-refractory lymphomas and NSCLC. Currently, AZD9150 is being studied in a phase I/II trial alone or in combination with other anti-cancer drugs in patients with NSCLC, lymphoma and different advanced solid tumors [38][39]. In addition, again with the aim of targeting STAT3 in lung cancer, Njatcha and colleagues employed a cyclic 15 nucleotide length decoy called CS3D [40]. The circular oligonucleotide was obtained through the inclusion of two hexaethyleneglycol spacers that provide flexibility and thermal stability. Effects obtained upon decoy ASO transfection in 201T and H1975 lung cancer cells include the reduction in cell growth and proliferation and the increase in apoptosis.

Another key protein regulating important pro-oncogenic pathways in cancer, which can be therefore considered an interesting therapeutic target, is PKC. A 20-mer phosphorothioate ASO (ISIS 3521) has been synthesized to bind the 3′ UTR region of PKC alpha mRNA. ISIS 3521 has been tested alone or in combination with chemotherapeutics for the treatment of NSCLC and different refractory cancers [41]. The ASO entered phase III clinical trials in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel, or with gemcitabine and cisplatin [42].

Combined therapeutic regimens in clinical trials for NSCLC include the use of an anti-clusterin ASO. Clusterin is a chaperone heterodimeric glycoprotein upregulated in many cancers, including NSCLC, and involved in the clearance of cellular debris and apoptosis. A 2′-methoxyethyl-modified phosphorothioate ASO (OGX-011) inhibiting the clusterin gene has been used in different kinds of tumors and is currently in phase I/II trial in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine, and in phase III in combination with docetaxel for the treatment of advanced NSCLC [43][44].

An additional interesting application of ASOs in NSCLC was described to counteract angiogenesis. Recent studies have shown that VEGFA is up-regulated in squamous cell carcinoma, due to the overexpression of the long non-coding (lnc) RNA LINC00173.v1, a RNA sponge sequestering miR-511-5p [45]. Importantly, ASOs inhibiting LINC00173.v1 were developed and tested in mice, alone or in combination with cisplatin. Lung cancer cells were inoculated in mice and one week later, the ASOs were injected intraperitoneally once weekly for 4 weeks. Results showed the ASO ability to effectively inhibit tumor growth, increase mice survival and improve the therapeutic sensitivity to cisplatin [45].

Self-renewing tumor-initiating cells (TICs) represent a small population within the tumor mass that strongly contribute to tumor progression, recurrence and drug resistance. In order to target this population, Lin J et al. designed innovative splicing-modulating steric hindrance antisense oligonucleotides (shAONs) targeting the glycine decarboxylase (GLDC) gene, whose protein is a metabolic enzyme overexpressed in TICs of NSCLC, and necessary for their maintenance [46]. The developed ASOs efficiently induced exon skipping with an IC50 of 3.5–7 nM, disrupting the GLDC open reading frame and resulting in the inhibition of cell proliferation and colony formation in A549 cells and NSCLC tumor spheres (TS32). Most importantly, the best shAON strongly inhibited tumor growth in mice xenografts of TS32.

Recently, the GTP-binding protein ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF)-like (ARL) 4C (ARL4C) has been explored as a potential therapeutic target for NSCLC treatment. An ASO targeting ARL4C, called ASO-1316, was synthesized and tested in NSCLC evaluating cell proliferation, migration and tumor sphere formation [47]. Obtained results demonstrated the ASO-1316 ability to suppress lung cancer cell proliferation and migration in vitro, regardless of KRAS or EGFR mutation.

4. MicroRNAs

MiRNAs are a group of endogenous short ncRNAs (18-25 nucleotides in length) that negatively regulate gene expression at a post-transcriptional level. They have attracted great attention as anticancer therapeutics given to their pivotal role in tumorigenesis [48]. Indeed, miRNAs are involved in the regulation of numerous metabolic and cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, migration and survival, and can act as oncosuppressors or oncogenes (oncomiRs) [49]. One main feature of miRNA function is their ability to target multiple pathways simultaneously, thus offering the possibility to improve the therapeutic efficacy of the treatment, decreasing the occurrence of drug resistance, a frequent event when only one pathway is targeted.

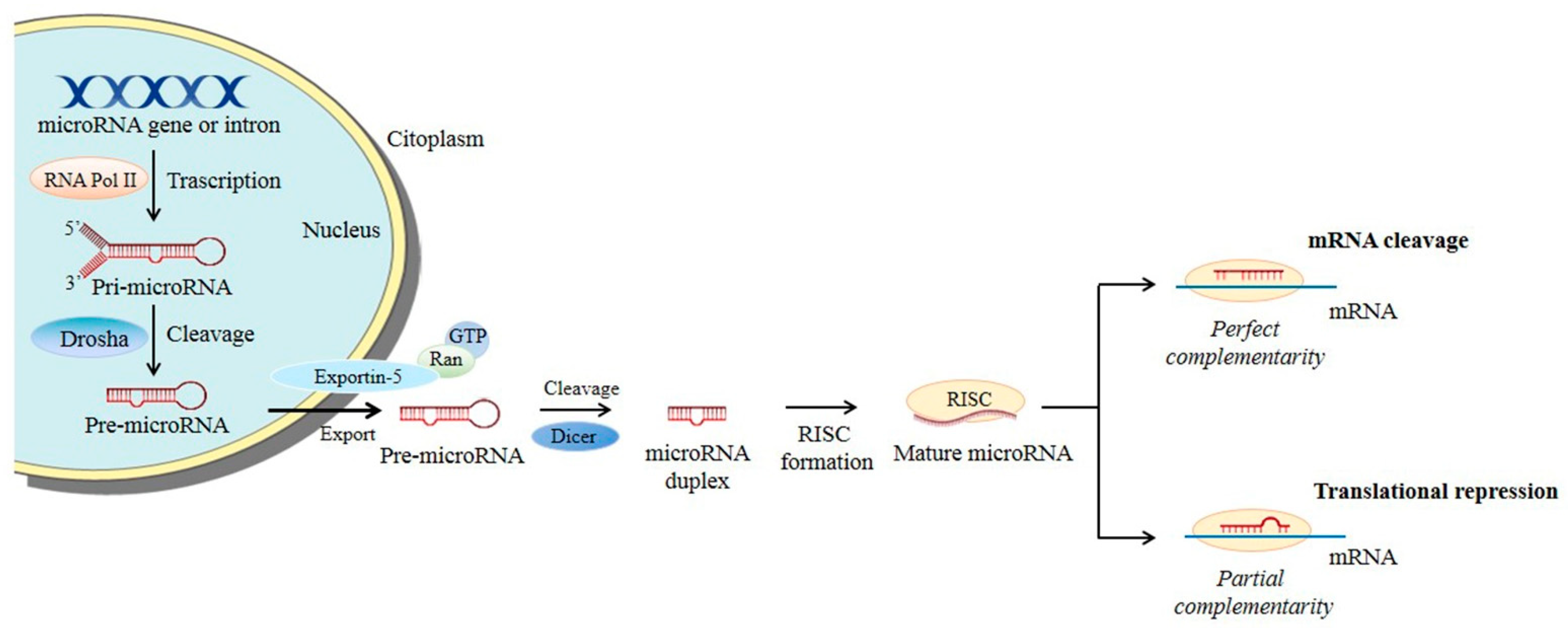

MiRNA biogenesis (Figure 3) starts in the nucleus where the RNA polymerase II transcribes a pri-miRNA molecule, a double-stranded precursor with a polyadenylated stem-loop structure at the 3’ and a cap at the 5’. Two RNases III sequentially process this pri-miRNA: Drosha, which forms the pre-miRNA, that is then translocated into the cytoplasm, and Dicer, which processes the pre-miRNA into a mature miRNA. At this point, the non-functional strand (passenger) in the mature miRNA is degraded, while the functional one (guide strand) is loaded into a complex called RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex) and, based on its complementarity with the target mRNA, mediates mRNA degradation or translation inhibition.

Figure 3. microRNA biogenesis. Main steps of microRNA processing. Briefly, miRNA transcripts (pri-miRNAs) are produced and cleaved by Drosha into pre-miRNAs. The pre-miRNAs are then exported into the cytoplasm by exportin-5–Ran-GTP and further processed into mature miRNA duplexes. The functional strand of the mature miRNA is thus guided by the RISC complex to the target mRNA permitting translational repression or mRNA cleavage.

Depending on the extent of miRNA expression in the tumor, different therapeutic approaches can be considered. When miRNAs are downregulated, they can be replaced by oligonucleotides that mimic their action or by viral vectors that allow miRNA expression to be restored. On the contrary, when miRNAs are over-expressed, they can be inhibited by: (i) synthetic anti-miRNAs, also known as antagomirs, that are ASOs complementary to the miRNA of interest able to induce the duplex formation and miRNA degradation; (ii) miRNA sponges that are competitive inhibitors containing multiple miRNA binding sites, allowing the simultaneous sequestering of multiple miRNAs [50]. The involvement of miRNAs in lung carcinogenesis has been widely documented by several studies focused on the differential expression pattern of miRNAs between lung tumor tissues and normal tissues [51].

Of note, despite different clinical trials for miRNA therapeutics are currently ongoing for a variety of cancers, including liver cancer, T-cell lymphoma, mesothelioma and lymphoma, only a few molecules are under clinical evaluation for lung cancer therapy, and only one for NSCLC [52].

The clinical study performed by van Zandwijk and colleagues involves the use of a miR-16 mimic enclosed in enveloped delivery vehicles (EDV), whose surface was functionalized with antibodies specifically targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), over-expressed in different cancer types, including NSCLC [53]. These complexes, called “TargomiR” showed encouraging results in a Phase I clinical trial in patients with recurrent malignant pleural mesothelioma and NSCLC.

MiR-21 is commonly over-expressed in solid tumors and targets oncosuppressor genes, such as Phosphatase and TENsin homolog (PTEN), Programmed Cell Death 4 (PDCD4) and Tropomyosin 1 (TPM1), promoting cell growth, metastasis and escape from the apoptosis. The involvement of miR-21 in NSCLC tumorigenesis and drug resistance has been widely studied [54]. Therefore, its modulation by anti-miRNAs encapsulated in various delivery systems has been investigated and showed promising results. In this regard, an interesting study comes from Wang et al. [55], who employed a PEG-functionalized nanographene oxide (NGO-PEG) dendrimer to deliver the anti-miR-21 to NSCLC. In order to monitor the delivery efficacy, authors included an activatable luciferase reporter gene, containing three miR-21 complementary sequences in the 3′ UTR, so that miR-21 inhibition results in an increase in the luciferase activity. The complexes effectively delivered the anti-miR-21 into the cytoplasm upregulating luciferase intensity, restoring PTEN expression and inhibiting cell migration and invasion. Moreover, the intravenous administration of the complex in NSCLC mouse xenografts allowed efficient delivery of the anti-miRNA.

MiR-150 has been proposed as a therapeutic target in different cancers, including NSCLC [56]. In particular, it has been reported to directly regulate the expression of Forkhead-box O 4 (FOXO4) and enhance tumor cell metastasis in NSCLC, both in vitro and in vivo in mouse xenograft models [57].

MiR-221/222 has been found to be upregulated in TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-resistant NSCLC cells. Its inhibition has been demonstrated to improve TRAIL sensitivity by targeting cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27Kip1) [58]. In addition to its therapeutic potential, miR-221 has been also proposed as a marker for early diagnosis and NSCLC screening [59].

MiR-96 is a potent oncomiR, which increases NSCLC chemoresistance by reducing the expression of Sterile Alpha Motif Domain Containing 9 (SAMD9) [60]. It has been demonstrated that anti-miR-96, in combination with cisplatin, is able to upregulate SAMD9 expression dramatically enhancing cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Although only in vitro data were provided, the study suggests a new approach to improve response to chemotherapy in NSCLC.

MiR-17/92 cluster includes six family members: miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-19b-1, miR-20a and miR-92a. Among them, miR-19 is the leading oncogenic player. The miR-17/92 cluster is typically amplified in lung cancer and targets different genes, such as Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α), PTEN, BCL2-like 11 (BCL2L11), cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) and Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), which are involved in cancer cell death and proliferation [61]. Matsubara et al. found that ASO-inhibiting miR-17-5p and miR-20a induced apoptosis in cancer cells overexpressing miR-17-92 [62].

Furthermore, several studies described the deregulation of miR-19a in various cancer types, and demonstrated that its upregulation strongly correlates with increased metastasis, invasiveness, and a poor prognosis in NSCLC [63]. The study conducted by Jing Li and colleagues showed that the upregulation of miR-19 (miR-19a and miR-19b-1) in A549 and HCC827 lung cancer cells triggered EMT transition, which led to mesenchymal-like morphological changes and increased cell migration and invasion. The authors also demonstrated that the miR-19 target, PTEN, had an important role in these processes, which were reverted when the miRNA was silenced [64].

In addition to over-expressed miRNAs, many others are downregulated, acting as tumor-suppressor genes. Below, researchers discuss some of the most interesting tumor-suppressor miRNAs in NSCLC.

MiR-Let-7 family includes 11 members, among which let-7a, let-7c, and let-7g are frequently downregulated in lung cancer patients. MiR-let-7 regulates the expression of several genes involved in cell proliferation and cell cycle, including cMyc, high-mobility group A (HMGA), STAT3, Janus-activated kinase 2 (JAK2), KRAS, Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 6 (CDK6), Homeobox A9 (HOXA9), transforming growth factor beta receptor 1 (TGFBR1), B-cell lymphoma-extra-large (BCL-XL) and Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 (MAP4K3) [65][66][67][68]. It has been widely demonstrated that transfection of miR-Let-7 family members significantly decreased the proliferation rate of NSCLC cells and improved the sensitivity to chemo and radiotherapy [69][70][71]. Further, it has been reported that Let-7 reduces tumor formation in vivo, in NSCLC orthotopic models following intranasal administration, modulating KRAS expression. Notably, an aptamer-based strategy for the targeted delivery of miR-Let-7g has been developed by Esposito CL and colleagues and successfully applied to NSCLC both in vitro and in vivo (see the paragraph on Aptamers for more details) [72].

MiR-29 family, including miR-29a, 29b and 29c, has been widely studied in NSCLC. A first report showed its ability to revert aberrant DNA methylation in lung cancer, by targeting the de novo DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) 3A and 3B. This leads to the re-expression of methylation-silenced tumor-suppressor genes, such as fragile histidine triad protein (FHIT), CDKN2A, cadherin-13 (CDH13), cadherin-1 (CDH1) and Ras Association Domain Family Member (RASSF1A) both in vitro and in vivo [73]. Next, Wu et al. demonstrated that miR-29 transfection by cationic lipoplexes significantly reduced the expression of cell division protein kinase 6 (CDK-6), DNMT3B and myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein 1 (MCL1) and inhibited tumor growth in subcutaneous xenograft models of A549 NSCLC cells [74]. More recently, Xing et al. confirmed the therapeutic potential of miR-29, by employing an N-isopropylacrylamide-modified PEI (namely PEN) as a carrier for miR-29a. The authors demonstrated the complex efficacy in allowing miR-29a delivery and processing with a consequent anti-proliferative and anti-migratory effect on A549 NSCLC cells [75].

MiR-200 family is known as a negative regulator of the EMT due to its ability to target Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox (ZEB) family members, acting as translational repressors that promote EMT [76]. MiR-200 decreases tumor survival by reducing the expression of VEGF and VEGF-R1 [77]. In a mouse model of lung adenocarcinoma (KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53flox/flox), metastasis was significantly increased by the deletion of miR-200c/141, resulting in a desmoplastic tumor stroma [78]. Within the stroma, the NOTCH signaling pathway is promoted by the downregulation of miR-200 in cancer-associated fibroblasts, improving the ability of cancer cells to metastasize [78]. In a group of NSCLC patients with adenocarcinoma, Tejero and colleagues recently showed that high levels of miR-141 and miR-200c are associated with shorter overall survival [79]. In addition, Cortez and co-workers have shown that miR-200c promotes radiosensitivity of lung cancer cells by controlling the oxidative stress response through the direct regulation of Peroxiredoxin 2 (PRDX2), GA-binding protein (GAPB/Nrf2) and Sestrin 1 (SESN1), and by preventing the repair of radiation-induced double-strand breaks [80]. The therapeutic potential of miR-200c in combination with other treatments, such as radiation, was also demonstrated in vivo.

MiR-34 family has been found to be deregulated in several human malignancies, and is considered a tumor-suppressive miRNA group due to its synergistic effect with the tumor suppressor gene p53 [81][82]. The miR-34 family has been shown to inhibit the translation of genes involved in cell growth, proliferation, cell cycle control and anti-apoptotic signaling [83]. In addition, several preclinical studies have shown the big potential of miR-34a in cancer treatment [84]. Kasinski et al. showed that miR-34a is a valuable therapeutic option for NSCLC treatment. They concluded that the administration of miR-34a to lung cancer patients with KRAS -positive and p53-negative tumors, slows tumor growth and potentially increases survival [85]. Notably, miR-34a was the first miRNA restoration therapy investigated in a clinical trial. Although the trial was ultimately unsuccessful [86], miR-34a is expected to be included in further miRNA mimic studies due to its potent tumor-suppressive effect in a variety of tumor subtypes.

References

- Cancer Facts & Figures 2022. American Cancer Society. 2022. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2022.html (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Economopoulou, P.; Mountzios, G. The emerging treatment landscape of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 138.

- Park, K.H.; Yang, J.-W.; Kwon, J.-H.; Lee, H.; Yoon, Y.D.; Choi, B.J.; Lee, M.Y.; Lee, C.W.; Han, S.-B.; Kang, J.S. Targeted Induction of Endogenous VDUP1 by Small Activating RNA Inhibits the Growth of Lung Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7743.

- Chernikov, I.V.; Ponomareva, U.A.; Chernolovskaya, E.L. Structural Modifications of siRNA Improve Its Performance In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 956.

- Khan, P.; Siddiqui, J.A.; Lakshmanan, I.; Ganti, A.K.; Salgia, R.; Jain, M.; Batra, S.K.; Nasser, M.W. RNA-based therapies: A cog in the wheel of lung cancer defense. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 54.

- Roberts, T.C.; Langer, R.; Wood, M.J.A. Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 673–694.

- Jin, J.-O.; Kim, G.; Hwang, J.; Han, K.H.; Kwak, M.; Lee, P.C. Nucleic acid nanotechnology for cancer treatment. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2020, 1874, 188377.

- Cui, H.; Zhu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, P.; Fang, J. Liver-Targeted Delivery of Oligonucleotides with N-Acetylgalactosamine Conjugation. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 16259–16265.

- Qian, Z.M. Targeted Drug Delivery via the Transferrin Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis Pathway. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002, 54, 561–587.

- Karpuz, M.; Silindir-Gunay, M.; Ozer, A.Y.; Ozturk, S.C.; Yanik, H.; Tuncel, M.; Aydin, C.; Esendagli, G. Diagnostic and therapeutic evaluation of folate-targeted paclitaxel and vinorelbine encapsulating theranostic liposomes for non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 156, 105576.

- Ledermann, J.; Canevari, S.; Thigpen, T. Targeting the folate receptor: Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to personalize cancer treatments. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2034–2043.

- Paunovska, K.; Loughrey, D.; Dahlman, J.E. Drug delivery systems for RNA therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 265–280.

- Dar, S.A.; Thakur, A.; Qureshi, A.; Kumar, M. siRNAmod: A database of experimentally validated chemically modified siRNAs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20031.

- Sipa, K.; Sochacka, E.; Kazmierczak-Baranska, J.; Maszewska, M.; Janicka, M.; Nowak, G.; Nawrot, B. Effect of base modifications on structure, thermodynamic stability, and gene silencing activity of short interfering RNA. Rna 2007, 13, 1301–1316.

- Meng, Z.; Lu, M. RNA Interference-Induced Innate Immunity, Off-Target Effect, or Immune Adjuvant? Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 331.

- Hornung, V.; Guenthner-Biller, M.; Bourquin, C.; Ablasser, A.; Schlee, M.; Uematsu, S.; Noronha, A.; Manoharan, M.; Akira, S.; De Fougerolles, A.; et al. Sequence-specific potent induction of IFN-α by short interfering RNA in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 263–270.

- Judge, A.D.; Sood, V.; Shaw, J.R.; Fang, D.; McClintock, K.; MacLachlan, I. Sequence-dependent stimulation of the mammalian innate immune response by synthetic siRNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 457–462.

- Broering, R.; Real, C.I.; John, M.J.; Jahn-Hofmann, K.; Ickenstein, L.M.; Kleinehr, K.; Paul, A.; Gibbert, K.; Dittmer, U.; Gerken, G.; et al. Chemical modifications on siRNAs avoid Toll-like-receptor-mediated activation of the hepatic immune system in vivo and in vitro. Int. Immunol. 2013, 26, 35–46.

- Hong, D.; Kurzrock, R.; Kim, Y.; Woessner, R.; Younes, A.; Nemunaitis, J.; Fowler, N.; Zhou, T.; Schmidt, J.; Jo, M.; et al. AZD9150, a next-generation antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of STAT3 with early evidence of clinical activity in lymphoma and lung cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 314ra185.

- Vansteenkiste, J.; Canon, J.-L.; Riska, H.; Pirker, R.; Peterson, P.; John, W.; Mali, P.; Lahn, M. Randomized phase II evaluation of aprinocarsen in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin for patients with advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Investig. New Drugs 2005, 23, 263–269.

- Zielinski, R.; Chi, K.N. Custirsen (OGX-011): A second-generation antisense inhibitor of clusterin in development for the treatment of prostate cancer. Futur. Oncol. 2012, 8, 1239–1251.

- Pastor, F.; Berraondo, P.; Etxeberria, I.; Frederick, J.; Sahin, U.; Gilboa, E.; Melero, I. An RNA toolbox for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 751–767.

- Bennett, C.F.; Swayze, E.E. RNA Targeting Therapeutics: Molecular Mechanisms of Antisense Oligonucleotides as a Therapeutic Platform. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 50, 259–293.

- Disterer, P.; Kryczka, A.; Liu, Y.; Badi, Y.E.; Wong, J.J.; Owen, J.S.; Khoo, B. Development of Therapeutic Splice-Switching Oligonucleotides. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014, 25, 587–598.

- Lima, W.F.; De Hoyos, C.L.; Liang, X.-H.; Crooke, S.T. RNA cleavage products generated by antisense oligonucleotides and siRNAs are processed by the RNA surveillance machinery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 3351–3363.

- Wu, H.; Lima, W.F.; Zhang, H.; Fan, A.; Sun, H.; Crooke, S.T. Determination of the Role of the Human RNase H1 in the Pharmacology of DNA-like Antisense Drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 17181–17189.

- Dhuri, K.; Bechtold, C.; Quijano, E.; Pham, H.; Gupta, A.; Vikram, A.; Bahal, R. Antisense Oligonucleotides: An Emerging Area in Drug Discovery and Development. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2004.

- Ramasamy, T.; Ruttala, H.B.; Munusamy, S.; Chakraborty, N.; Kim, J.O. Nano drug delivery systems for antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) therapeutics. J. Control. Release 2022, 352, 861–878.

- Curreri, A.; Sankholkar, D.; Mitragotri, S.; Zhao, Z. RNA therapeutics in the clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022, 8, e10374.

- Kim, H.S.; Mendiratta, S.; Kim, J.; Pecot, C.V.; Larsen, J.; Zubovych, I.; Seo, B.Y.; Kim, J.; Eskiocak, B.; Chung, H.; et al. Systematic Identification of Molecular Subtype-Selective Vulnerabilities in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cell 2013, 155, 552–566.

- Matikas, A.; Mistriotis, D.; Georgoulias, V.; Kotsakis, A. Targeting KRAS mutated non-small cell lung cancer: A history of failures and a future of hope for a diverse entity. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 110, 1–12.

- Ross, S.J.; Revenko, A.S.; Hanson, L.L.; Ellston, R.; Staniszewska, A.; Whalley, N.; Pandey, S.K.; Revill, M.; Rooney, C.; Buckett, L.K.; et al. Targeting KRAS-dependent tumors with AZD4785, a high-affinity therapeutic antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of KRAS. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal5253.

- Wang, D.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P.; Lu, X.; Jia, F.; Sun, Y.; Sun, T.; Zhang, L.; Che, F.; et al. Targeting oncogenic KRAS with molecular brush-conjugated antisense oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113180119.

- Han, B.; Park, D.; Li, R.; Xie, M.; Owonikoko, T.K.; Zhang, G.; Sica, G.L.; Ding, C.; Zhou, J.; Magis, A.T.; et al. Small-Molecule Bcl2 BH4 Antagonist for Lung Cancer Therapy. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 852–863.

- Minegishi, K.; Dobashi, Y.; Tsubochi, H.; Tokuda, R.; Okudela, K.; Ooi, A. Screening of the copy number increase of AKT in lung carcinoma by custom-designed MLPA. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 3344–3356.

- Cheng, X.; Yu, D.; Cheng, G.; Yung, B.C.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Kang, C.; Fang, X.; Tian, S.; Zhou, X.; et al. T7 Peptide-Conjugated Lipid Nanoparticles for Dual Modulation of Bcl-2 and Akt-1 in Lung and Cervical Carcinomas. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 4722–4732.

- Cheng, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Kang, C.; Liu, Y.; Guo, T.; Shang, K.; Yan, C.; Cheng, G.; Lee, R.J. Lipid Nanoparticles Loaded with an Antisense Oligonucleotide Gapmer Against Bcl-2 for Treatment of Lung Cancer. Pharm. Res. 2016, 34, 310–320.

- Nishina, T.; Fujita, T.; Yoshizuka, N.; Sugibayashi, K.; Murayama, K.; Kuboki, Y. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and preliminary antitumour activity of an antisense oligonucleotide targeting STAT3 (danvatirsen) as monotherapy and in combination with durvalumab in Japanese patients with advanced solid malignancies: A phase 1 study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055718.

- Ribrag, V.; Lee, S.T.; Rizzieri, D.; Dyer, M.J.; Fayad, L.; Kurzrock, R.; Andritsos, L.; Bouabdallah, R.; Hayat, A.; Bacon, L.; et al. A Phase 1b Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Durvalumab in Combination With Tremelimumab or Danvatirsen in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020, 21, 309–317.e3.

- Njatcha, C.; Farooqui, M.; Kornberg, A.; Johnson, D.E.; Grandis, J.R.; Siegfried, J.M. STAT3 Cyclic Decoy Demonstrates Robust Antitumor Effects in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 1917–1926.

- Li, K.; Zhang, J. ISIS-3521. Isis Pharmaceuticals. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2001, 2, 1454–1461.

- Kurtz, D.T. Affinitak. In xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference; Enna, S.J., Bylund, D.B., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1–5.

- Laskin, J.J.; Chi, K.N.; Melosky, B.; Sill, K.; Hao, D.; Canil, C.M.; Gleave, M.; Murray, N. Phase I study of OGX-011, a second generation antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) to clusterin, combined with cisplatin and gemcitabine as first-line treatment for patients with stage IIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 17078.

- Laskin, J.J.; Hao, D.; Canil, C.; Lee, C.W.; Stephenson, J.; Vincent, M.; Gitlitz, B.; Cheng, S.; Murray, N.R. A phase I/II study of OGX-011 and a gemcitabine (GEM)/platinum regimen as first-line therapy in 85 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 7596.

- Chen, J.; Liu, A.; Wang, Z.; Wang, B.; Chai, X.; Lu, W.; Cao, T.; Li, R.; Wu, M.; Lu, Z.; et al. LINC00173.v1 promotes angiogenesis and progression of lung squamous cell carcinoma by sponging miR-511-5p to regulate VEGFA expression. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 98.

- Lin, J.; Lee, J.H.J.; Paramasivam, K.; Pathak, E.; Wang, Z.; Pramono, Z.A.D.; Lim, B.; Wee, K.B.; Surana, U. Induced-Decay of Glycine Decarboxylase Transcripts as an Anticancer Therapeutic Strategy for Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2017, 9, 263–273.

- Kimura, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Harada, T.; Morii, E.; Nagatomo, I.; Shintani, Y.; Kikuchi, A. ARL4C is associated with initiation and progression of lung adenocarcinoma and represents a therapeutic target. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 951–961.

- Guz, M.; Rivero-Müller, A.; Okoń, E.; Stenzel-Bembenek, A.; Polberg, K.; Słomka, M.; Stepulak, A. MicroRNAs-Role in Lung Cancer. Dis. Markers 2014, 2014, 218169.

- Annese, T.; Tamma, R.; De Giorgis, M.; Ribatti, D. microRNAs Biogenesis, Functions and Role in Tumor Angiogenesis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 581007.

- Abd-Aziz, N.; Kamaruzman, N.I.; Poh, C.L. Development of MicroRNAs as Potential Therapeutics against Cancer. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 8029721.

- Zhu, X.; Kudo, M.; Huang, X.; Sui, H.; Tian, H.; Croce, C.M.; Cui, R. Frontiers of MicroRNA Signature in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 643942.

- Reda El Sayed, S.; Cristante, J.; Guyon, L.; Denis, J.; Chabre, O.; Cherradi, N. MicroRNA Therapeutics in Cancer: Current Advances and Challenges. Cancers 2021, 13, 2680.

- Reid, G.; Kao, S.C.; Pavlakis, N.; Brahmbhatt, H.; MacDiarmid, J.; Clarke, S.; Boyer, M.; van Zandwijk, N. Clinical development of TargomiRs, a miRNA mimic-based treatment for patients with recurrent thoracic cancer. Epigenomics 2016, 8, 1079–1085.

- Bica-Pop, C.; Cojocneanu-Petric, R.; Magdo, L.; Raduly, L.; Gulei, D.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. Overview upon miR-21 in lung cancer: Focus on NSCLC. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3539–3551.

- Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, L.; Shi, Y.; Li, Z.; Xia, Y.; Tian, J. Imaging Dendrimer-Grafted Graphene Oxide Mediated Anti-miR-21 Delivery With an Activatable Luciferase Reporter. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 9014–9021.

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, D.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Microvesicle-delivery miR-150 promotes tumorigenesis by up-regulating VEGF, and the neutralization of miR-150 attenuate tumor development. Protein Cell 2013, 4, 932–941.

- Li, H.; Ouyang, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Chen, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, M.; Wang, W.; et al. MiR-150 promotes cellular metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer by targeting FOXO4. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39001.

- Garofalo, M.; Quintavalle, C.; Di Leva, G.; Zanca, C.; Romano, G.; Taccioli, C.; Liu, C.G.; Croce, C.M.; Condorelli, G. MicroRNA signatures of TRAIL resistance in human non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2008, 27, 3845–3855.

- Ghany, S.M.A.; Ali, E.M.; Ahmed, A.; Hozayen, W.G.; Mohamed-Hussein, A.A.; Elnaggar, M.S.; Hetta, H.F. Circulating miRNA-30a and miRNA-221 as Novel Biomarkers for the Early Detection of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Middle East J. Cancer 2020, 11, 50–58.

- Wu, L.; Pu, X.; Wang, Q.; Cao, J.; Xu, F.; Xu, L.; Li, K. miR-96 induces cisplatin chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells by downregulating SAMD9. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 11, 945–952.

- Hayashita, Y.; Osada, H.; Tatematsu, Y.; Yamada, H.; Yanagisawa, K.; Tomida, S.; Yatabe, Y.; Kawahara, K.; Sekido, Y.; Takahashi, T. A Polycistronic MicroRNA Cluster, miR-17-92, Is Overexpressed in Human Lung Cancers and Enhances Cell Proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 9628–9632.

- Matsubara, H.; Takeuchi, T.; Nishikawa, E.; Yanagisawa, K.; Hayashita, Y.; Ebi, H.; Yamada, H.; Suzuki, M.; Nagino, M.; Nimura, Y.; et al. Apoptosis induction by antisense oligonucleotides against miR-17-5p and miR-20a in lung cancers overexpressing miR-17-92. Oncogene 2007, 26, 6099–6105.

- Lin, Q.; Chen, T.; Lin, Q.; Lin, G.; Lin, J.; Chen, G.; Guo, L. Serum miR-19a expression correlates with worse prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 107, 767–771.

- Li, J.; Yang, S.; Yan, W.; Yang, J.; Qin, Y.-J.; Lin, X.-L.; Xie, R.-Y.; Wang, S.-C.; Jin, W.; Gao, F.; et al. MicroRNA-19 triggers epithelial–mesenchymal transition of lung cancer cells accompanied by growth inhibition. Lab. Investig. 2015, 95, 1056–1070.

- Johnson, C.D.; Esquela-Kerscher, A.; Stefani, G.; Byrom, M.; Kelnar, K.; Ovcharenko, D.; Wilson, M.; Wang, X.; Shelton, J.; Shingara, J.; et al. The let-7 MicroRNA Represses Cell Proliferation Pathways in Human Cells. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 7713–7722.

- Johnson, S.M.; Grosshans, H.; Shingara, J.; Byrom, M.; Jarvis, R.; Cheng, A.; Labourier, E.; Reinert, K.L.; Brown, D.; Slack, F.J. RAS Is Regulated by the let-7 MicroRNA Family. Cell 2005, 120, 635–647.

- Kumar, M.S.; Erkeland, S.J.; Pester, R.E.; Chen, C.Y.; Ebert, M.S.; Sharp, P.A.; Jacks, T. Suppression of non-small cell lung tumor development by the let-7 microRNA family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3903–3908.

- Lee, Y.S.; Dutta, A. The tumor suppressor microRNA let-7 represses the HMGA2 oncogene. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 1025–1030.

- Dai, X.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, C. Let-7 Sensitizes KRAS Mutant Tumor Cells to Chemotherapy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126653.

- Liu, J.-K.; Liu, H.-F.; Ding, Y.; Gao, G.-D. Predictive value of microRNA let-7a expression for efficacy and prognosis of radiotherapy in patients with lung cancer brain metastasis: A case-control study. Medicine 2018, 97, e12847.

- Yin, J.; Hu, W.; Pan, L.; Fu, W.; Dai, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, J. let-7 and miR-17 promote self-renewal and drive gefitinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 42, 495–508.

- Esposito, C.; Cerchia, L.; Catuogno, S.; De Vita, G.; Dassie, J.P.; Santamaria, G.; Swiderski, P.; Condorelli, G.; Giangrande, P.H.; de Franciscis, V. Multifunctional Aptamer-miRNA Conjugates for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 1151–1163.

- Fabbri, M.; Garzon, R.; Cimmino, A.; Liu, Z.; Zanesi, N.; Callegari, E.; Liu, S.; Alder, H.; Costinean, S.; Fernandez-Cymering, C.; et al. MicroRNA-29 family reverts aberrant methylation in lung cancer by targeting DNA methyltransferases 3A and 3B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15805–15810.

- Wu, Y.; Crawford, M.; Mao, Y.; Lee, R.J.; Davis, I.C.; Elton, T.S.; Lee, L.J.; Nana-Sinkam, S.P. Therapeutic Delivery of MicroRNA-29b by Cationic Lipoplexes for Lung Cancer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2013, 2, e84.

- Xing, J.; Jia, J.; Cong, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q. N-Isopropylacrylamide-modified polyethylenimine-mediated miR-29a delivery to inhibit the proliferation and migration of lung cancer cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 198, 111463.

- Muto, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Kato, T.; Tsujinaka, S.; Ichida, K.; Takayama, Y.; Fukui, T.; Kakizawa, N.; Watanabe, F.; Saito, M.; et al. Heterogeneous expression of zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 plays a pivotal role in metastasis via regulation of miR-200c in epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 1057–1067.

- Roybal, J.D.; Zang, Y.; Ahn, Y.-H.; Yang, Y.; Gibbons, D.L.; Baird, B.N.; Alvarez, C.; Thilaganathan, N.; Liu, D.D.; Saintigny, P.; et al. miR-200 Inhibits Lung Adenocarcinoma Cell Invasion and Metastasis by Targeting Flt1/VEGFR1. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011, 9, 25–35.

- Xue, B.; Chuang, C.-H.; Prosser, H.M.; Fuziwara, C.S.; Chan, C.; Sahasrabudhe, N.; Kühn, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Biton, A.; et al. miR-200 deficiency promotes lung cancer metastasis by activating Notch signaling in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Genes Dev. 2021, 35, 1109–1122.

- Tejero-Villalba, R.; Navarro, A.; Campayo, M.; Viñolas, N.; Marrades, R.M.; Cordeiro, A.; Ruíz-Martínez, M.; Santasusagna, S.; Molins, L.; Ramirez, J.; et al. miR-141 and miR-200c as Markers of Overall Survival in Early Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Adenocarcinoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101899.

- Cortez, M.A.; Valdecanas, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhan, Y.; Bhardwaj, V.; Calin, G.A.; Komaki, R.; Giri, D.K.; Quini, C.C.; Wolfe, T.; et al. Therapeutic Delivery of miR-200c Enhances Radiosensitivity in Lung Cancer. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2014, 22, 1494–1503.

- He, L.; He, X.; Lim, L.P.; de Stanchina, E.; Xuan, Z.; Liang, Y.; Xue, W.; Zender, L.; Magnus, J.; Ridzon, D.; et al. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature 2007, 447, 1130–1134.

- Zhang, L.; Liao, Y.; Tang, L. MicroRNA-34 family: A potential tumor suppressor and therapeutic candidate in cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 53.

- Hermeking, H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 17, 193–199.

- Wang, C.; Jia, Q.; Guo, X.; Li, K.; Chen, W.; Shen, Q.; Xu, C.; Fu, Y. microRNA-34 family: From mechanism to potential applications. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2022, 144, 106168.

- Kasinski, A.L.; Slack, F.J. miRNA-34 Prevents Cancer Initiation and Progression in a Therapeutically Resistant K-ras and p53-Induced Mouse Model of Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2012, 72, 5576–5587.

- Hong, D.S.; Kang, Y.K.; Borad, M.; Sachdev, J.; Ejadi, S.; Lim, H.Y.; Brenner, A.J.; Park, K.; Lee, J.L.; Kim, T.Y.; et al. Phase 1 study of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 1630–1637.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

808

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 Apr 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No