Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flavia Trionfetti | -- | 3776 | 2023-03-27 12:17:19 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -4 word(s) | 3772 | 2023-03-28 03:24:38 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Trionfetti, F.; Marchant, V.; González-Mateo, G.T.; Kawka, E.; Márquez-Expósito, L.; Ortiz, A.; López-Cabrera, M.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Strippoli, R. Peritoneal Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42557 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Trionfetti F, Marchant V, González-Mateo GT, Kawka E, Márquez-Expósito L, Ortiz A, et al. Peritoneal Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42557. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Trionfetti, Flavia, Vanessa Marchant, Guadalupe T. González-Mateo, Edyta Kawka, Laura Márquez-Expósito, Alberto Ortiz, Manuel López-Cabrera, Marta Ruiz-Ortega, Raffaele Strippoli. "Peritoneal Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42557 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Trionfetti, F., Marchant, V., González-Mateo, G.T., Kawka, E., Márquez-Expósito, L., Ortiz, A., López-Cabrera, M., Ruiz-Ortega, M., & Strippoli, R. (2023, March 27). Peritoneal Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42557

Trionfetti, Flavia, et al. "Peritoneal Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 March, 2023.

Copy Citation

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) incidence is growing worldwide, with a significant percentage of CKD patients reaching end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and requiring kidney replacement therapies (KRT). Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a convenient KRT presenting benefices as home therapy. In PD patients, the peritoneum is chronically exposed to PD fluids containing supraphysiologic concentrations of glucose or other osmotic agents, leading to the activation of cellular and molecular processes of damage, including inflammation and fibrosis.

peritoneal dialysis

inflammation

peritoneal fibrosis

immune system

COVID-19

kidney

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) will become the fifth greatest global cause of death by 2040 and the second cause of death before the end of the century in those countries with longer life expectancy, as predicted by the Global Burden of Disease study and the Spanish Society of Nephrology [1][2][3]. Current therapies only retards CKD progression and many people present an increased risk of requiring kidney replacement therapy (KRT), of cardiovascular complications, and of all death causes [2][3]. KRT includes peritoneal dialysis (PD), hemodialysis, or renal transplantation. CKD increases the risk of death in COVID-19 patients, but also SARS-CoV-2 viral infection can complicate kidney damage by different mechanisms [4][5][6][7][8]. Renal complications in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic studies pointed out an active role of viral infection in the worsening prognosis of patients suffering acute kidney injury (AKI). Remarkably, the fatality rate of AKI patients with SARS viral infection is more than 90% [9].

Current PD therapy is focused on solute (toxin) removal and fluid balance. The repeated infusion of peritoneal dialysis fluids (PDFs) into the peritoneal cavity not only partially replaces renal function, but also induces an array of local and systemic untoward effects. During PD therapy, the peritoneal membrane (PM) is continuously exposed to supraphysiologic concentrations of glucose. In addition, the formation of glucose degradation products (GDPs) during heat sterilization of PDFs is believed to be key factors in the limited biocompatibility of PDFs. This chronic exposure to PDFs can induce several cellular and molecular responses in the PM, including sterile inflammation, loss of the mesothelial cell (MC) monolayer, submesothelial fibrosis, vasculopathy, and angiogenesis [10][11]. Moreover, peritoneal infections, mainly by episodes of acute bacterial peritonitis, can also occur during PD treatment and catheter maintenance [11]. All these events contribute to morphologic and functional PM transformation and ultimately technique failure often found in long-term PD patients [12]. On the other hand, the systemic effects of PDFs chronic exposure comprise a metabolic, inflammatory, and immune-modulatory burden. The impact of this to patient outcome has, however, not yet been properly delineated. Importantly, the newer PDFs, including biocompatible glucose-based solutions, icodextrin, taurine, and other recently proposed solutions based in alternative osmotic agents (stevia, xylitol, and L-carnitine), as well as the addition of potentially protective compounds, such as alanyl-glutamine supplementation, exert lower deleterious effects in the PM [13][14][15][16][17]. Despite PD therapy, CKD patients remain at high risk of poor outcomes. Most notably, cardiovascular events and markers of systemic inflammation are strongly associated with CKD patients [14][18]. The life expectancy of patients requiring KRT overall is inferior to that for most common cancers, including those originating in the breast, lung, and colon [19].

2. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Implicated in the Damage of the Peritoneum

Peritoneal damage depends on complex interactions between external stimuli, intrinsic properties of the PM, and subsequent activities of the local innate-adaptive immune system [20]. In PD patients, repeated exposure of the PM to PDFs can induce a local inflammatory response, that is mediated by the activation of different inflammatory pathways, such as the NLRP3 inflammasome and the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathways [21][22]. Several cell types are involved in this sterile inflammatory response, including the MCs themselves, neutrophils, mast cells, monocytes/macrophages (MØs), T lymphocytes, dendritic cells (DCs) and resident fibroblasts [20][23]. Furthermore, toll-like receptors (TLRs) mediate sterile inflammation by recognizing damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released by cellular stress [24]. In infectious conditions, there is an overproduction of cytokines that is mainly regulated by a complex network involving various immune cells [25]. PM is also potentially exposed to microorganisms’ infections due to its proximity to the intestine from where in pathological conditions microorganisms may reach the peritoneal cavity. Moreover, external factors may contribute to the entry of microorganisms into peritoneum space, such as medical actions of catheter positioning and maintenance, the practice of peritoneal dialysis, and abdominal surgery [26]. Postoperative peritonitis accounts up to 65% of abdominal infection observed in intensive care unit patients [27], so it is considered the most frequent form of intra-abdominal infection [28]. In PD patients, emergency treatment of this clinical complication by acute infections employs standardized protocols and has a high success rate, but patients experiencing peritonitis have increased technique failure and cardiovascular complication rates through ill-defined mechanisms [18][28].

2.1. Microorganisms Involved in Peritonitis Episodes during PD

Gram-positive bacteria of the skin play a major role in causing peritonitis episodes, with a minor role of Gram-negative bacteria, presumably originating from the enteric flora [29]. Viral infections of PM are scarcely reported in peritonitis cases due to the lack of standard diagnosis tests. Despite this, the suspect of viral infection occurs when peritonitis microbial culture results negative, an event occurring around 20% of the cases [30]. Literature reports cases of viral infection in peritonitis, such as coxackievirus B1 infection characterized by the presence of monocytosis in PD effluent [31]. It has also been demonstrated that viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus (VHSV) can infect the peritoneal cavity, activating the expansion and differentiation of a particular class of resident IgM+ B cells [32]. Also, less studied are peritonitis caused by fungal infections. They account for between 1 and 15% of all PD-associated peritonitis episodes, constituting a serious complication for PD patients. Most of these episodes are caused by Candida species such as Candida albicans [33][34].

2.2. Receptors and Ligands Implicated in the Infection of the Peritoneum

Innate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are the sensors implicated in PM damage by infectious and endogenous causes. These include TLRs, a retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors, NOD-like receptors, and C-type lectin receptors. The intracellular signaling cascade activated by PRRs determines the expression of inflammatory mediators acting in the elimination of pathogens and infected cells [35]. PRRs are able to recognize molecules conserved among microbial species called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) as well as DAMPs [24][36]. Among PRRs, TLRs play a critical role in the innate immune response by specifically recognizing molecular patterns from a wide range of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses. TLRs are responsible for sensing invading pathogens outside of the cell and in intracellular endosomes and lysosomes [35]. Ten different TLRs in humans and twelve in mice have been identified so far. Each of them recognizes different molecular patterns of microorganisms and self-components. TLR2 and TLR5 recognize Gram-positive bacteria [37], both more singularly than cross-talking to better counteract bacterial infections [38]. TLR2 can recognize a large number of microbial molecules in part by hetero-dimerization with other TLRs, such as TLR1 and TLR6, or unrelated receptors, such as Dectin-1, CD36, and CD14. TLR5 recognizes flagellin, a flagellum component in many motile bacteria [39]. TLR4 was initially identified as the detector for lipopolysaccharide (LPS), inducing response against Gram-negative bacteria. A set of TLRs, comprising TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9, act in the intracellular space to recognize nucleic acids derived from viruses and bacteria, as well as endogenous nucleic acids in pathogenic contexts [35]. TLR3 mediates the recognition of viral stimuli and is functionally expressed in peritoneal MCs [40]. TLR3 was demonstrated acting on fibrosis onset, in particular on matrix-remodeling proteins as it is correlated in time- and dose-dependent upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 and metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 (TIMP1) [41]. Several studies have demonstrated the active role of TLRs in modulating peritoneal fibrosis, particularly focusing on TLR2, critical for the recognition of an S. epidermidis-derived cell-free supernatant, which has been extensively utilized to model acute peritoneal inflammation [42][43]. Treatment with soluble Toll-like receptor 2, a TLR2 inhibitor, has also been shown to substantially reduce inflammation in an experimental in vivo model of S. epidermidis infection [24].

2.3. Role of Polymorphonucleate Neutrophils in Acute Infection and Early Innate Response

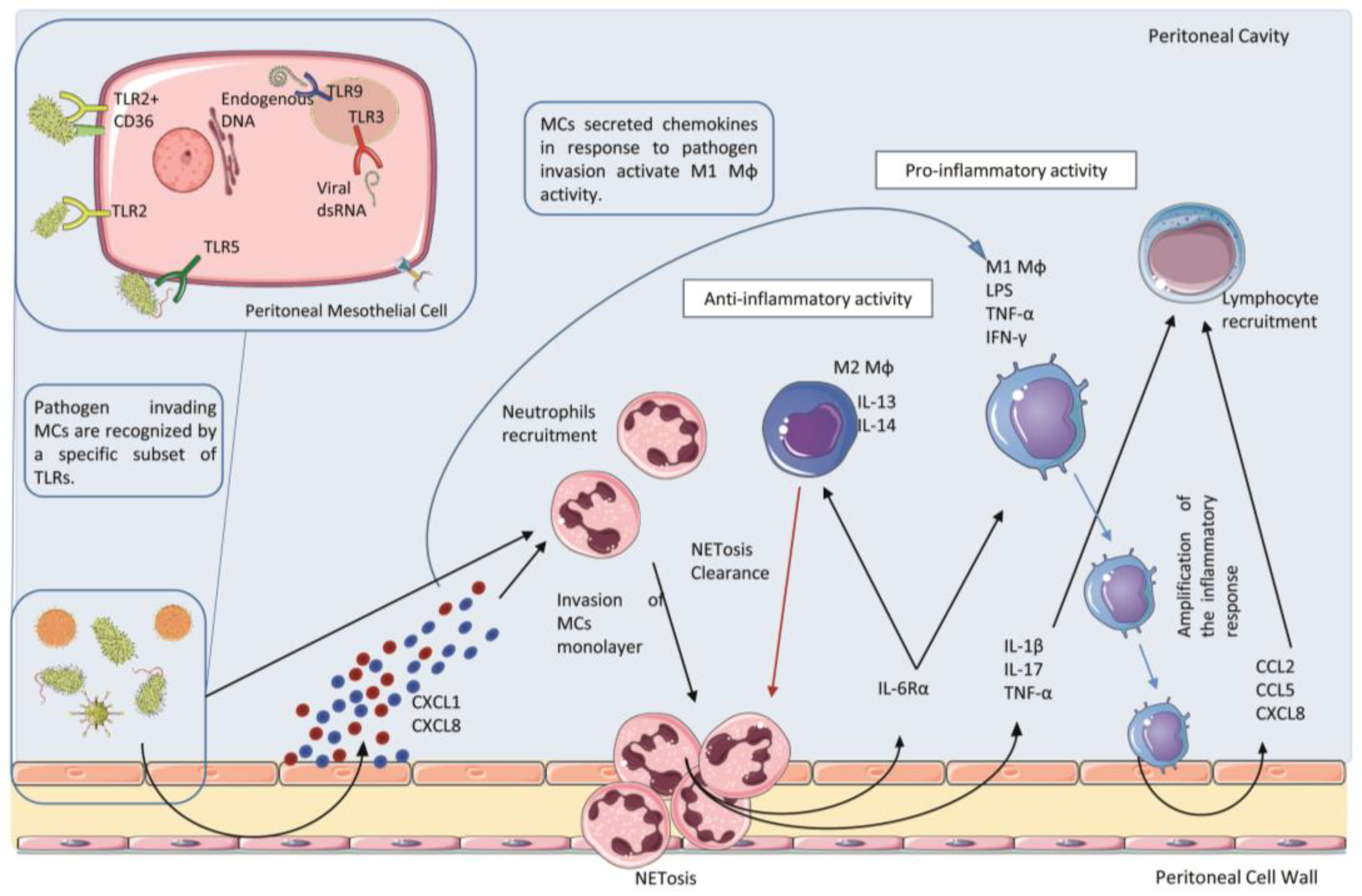

Pathogen-associated infection in the peritoneum first promotes a wave of polymorphonuclear neutrophils recruited by chemoattractants of bacterial origin or by chemokines, such as the C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 1 and CXCL8, produced mainly by MCs and omental fibroblasts. Neutrophils can use high endothelial venules present in anatomic structures called milky spots or fat-associated lymphoid clusters (FALCs) to enter the peritoneal cavity under the guidance of CXCL1 [44] (Figure 1). Neutrophil influx in the peritoneal cavity causes an initial inflammatory response driven by neutrophil-secreted proteases and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Secondly, once entered in peritoneum neutrophils undergo NETosis, which consists of the release of necrotic cell DNA forming a net of aggregated neutrophils able to trap and sequester microorganisms in FALCs, thus limiting their spreading [45]. Neutrophils also participated in the recruitment of mononuclear infiltrates through secreting IL6Rα, a shed form of interleukin (IL)-6 receptor. The local increase of IL-6Rα promotes an IL-6-mediated neutrophil clearance after mononuclear cell recruitment through a mechanism called trans-signaling [46][47]. Apoptotic neutrophils are phagocytized by MØs and to a lesser extent by the same MCs [48]. Necrotic neutrophils and NETs promote the infiltration of mature MØs recruited also by locally produced chemokines, such as CXCL8 and CCL2 [49]. Two other cytokines, IL-17A and interferon (IFN)-γ, also regulate neutrophil functions, including their influx in the peritoneum and clearance process [50].

Figure 1. Acute infection and early innate response in the peritoneum. Mesothelial cells (MCs) can sense invading microorganisms through a specific subset of Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs). Pathogen infection stimulates MCs to produce chemokines, such as CXCL1 and CLXL8, which promote the recruitment of a first wave of neutrophils entering the peritoneal cavity and undergo to the process of NETosis. Cytokines and chemokines released both by MCs and Neutrophils during this first wave of the inflammatory process induce the recruitment of mononuclear phagocyte. Macrophages (MØs) recruited in this area display different phenotype subtypes. M1 subtype shows pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic properties, whereas the M2 subtype presents an anti-inflammatory activity. Moreover, M2 MØs play a key role in the clearance of neutrophils debris due to scavenger activity. To activate the adaptative immune response, M1 MØs secrete CCL2, CCL5 and CXCL8 which acts as a chemoattractant for lymphocyte recruitment in the peritoneal cavity.

2.4. Role of Polymorphonucleate Macrophages and Dendritic Cells in Acute Infection and Chronic Inflammation

Peritoneal tissue-resident cells include MØs and DCs, as components of the peritoneal immune system. They participate in the induction of inflammatory response, pathogen clearance, tissue repair, and antigen presentation [51][52].

MØs are plastic cells involved in different diseases, playing both essential protective and pathological roles [51][52]. MØs can present two different phenotypes, named M1 and M2, which exert different properties and functions. Briefly, M1 MØs are involved in amplifying the first phase of the inflammatory process creating a gradient of chemotactic cytokines, such as CXCL8, C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)-2, and CCL5, necessary for the recruitment of other leukocytes. This process is concomitant to cytokine-driven up-regulation of adhesion molecules expression (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) on the surface of MCs, which facilitates leukocyte adhesion to MCs. Instead, M2 MØs actively counteract the inflammatory process through the production of soluble anti-inflammatory mediators, and the clearance of debris such as apoptotic or necrotic products, due to their scavenger activity [53].

MØs can be considered the major resident immune population in the PM where they play an essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis [54], being the predominant cell type found in dialysis effluent [55][56]. Under inflammatory or infection conditions, a depletion of resident peritoneal MØs populations has been reported [57], a phenomenon known as Macrophage Disappearance Reaction (MDR) [58]). In contrast, reducing the influx of monocytes derived MØs or depleting all MØs populations usually prevents injury in experimental models of peritoneal damage [59]. Primary peritoneal M2 MØs exhibited superior anti-inflammatory potential than immobilized cell lines. Interestingly, a high number of MØs, neutrophils, or a higher ratio of MØs/DCs can be associated with severe and recurrent episodes of peritonitis [55]. Moreover, peritoneal resident M2 MØs have been demonstrated to have an active role in attenuating the cytokine storm in severe acute infections [60].

A recent study showed that chronic exposure to PDFs alters resident MØs homeostatic phenotype, including the lost expression of anti-inflammatory and efferocytosis markers and enhanced inflammatory response [61]. Another study demonstrated the role of M1 instead of M2 MØs in peritoneal damage by depleting and transplanting different MØs populations into PDF-exposed mice [62]. In contrast, another study reported increased expression of the M2 MØs markers CD206, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), Ym-1, and Arginase-1 in experimental PDF exposure, together with fibrosis markers, which were recovered by clodronate-liposome-mediated MØs depletion [63]. In a peritoneal damage model induced by sodium hypochlorite, inflammatory M2 MØs switch to CCL-17-expressing profibrotic phenotype to promote fibroblasts activation [64].

In patients on continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD), a decrease in peritoneal MØs function has been observed [65], together with alterations in MØs heterogeneity (i.e., different maturation and activation states), which have been associated with different PD outcomes [55]. Moreover, peritoneal MØs isolated from patients under CAPD during peritonitis episodes exhibit increased proinflammatory cytokines expressions, such as IL-1β and tumoral necrosis factor (TNF)-α, compared to macrophages from CAPD patients without peritonitis [66]. Additional studies showed that peritoneal CD206+CD163+ M2 MØs are present in PD effluents of PD patients with peritonitis and that these MØs contribute to peritoneal fibrosis by stimulating fibroblast cell growth and increasing the production of the soluble factor CCL-18 [67]. Thus, the role of MØs during PDF-induced peritoneal damage depends on the pathological context and MØs subtype. Therefore, therapeutic approaches targeting the overall MØs population must be evaluated as resident peritoneal MØs play a key role in peritoneal immunity.

2.5. Role of Th17 Lymphocytes and Its Effector Cytokine IL-17A in Acute Infection and Chronic Inflammation

Th17 cells are a type of differentiated T helper lymphocytes characterized by a specific secretome including cytokines of the IL-17 family, mainly IL-17A, its effector cytokine, and other Th17-specific cytokines, such as IL-22, IL-26, and CCL20 [68]. Th17 plays a key role in the response against pathogens but is also implicated in the pathogenesis of many inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis [69]. Besides Th17 cells, IL-17A can be secreted by various leukocyte subpopulations, including neutrophils, Th1, and γδ-T lymphocytes and its expression correlated with the duration of the PD treatment and with the extent of peritoneal inflammation and fibrosis [50][70]. In peritoneal biopsies of PD patients, IL17-positive cells were identified as Th17 cells, γδ lymphocytes, mast cells, and neutrophils, and were positively correlated with peritoneal fibrosis [70].

Several experimental evidence shows the involvement of Th17/IL17A in acute peritoneal damage. In a murine model of intraperitoneal sepsis with abscess formation, an increase in the number of Th17 cells in the peritoneal cavity was observed, whereas the treatment with a neutralizing antibody against IL-17A prevented the abscesses formation [71]. Curiously, in peritonitis induced by S. aureus delivery and caecal ligation and puncture (CLP) in mice, γδ T lymphocytes, instead of Th17 cells, were found as the main source of IL-17A [72]. In the CLP model, intraperitoneal IL-17A and other cytokine levels were increased and IL-17A neutralization reduced proinflammatory cytokine levels and improved mice survival [73]. As commented before, IL-17A regulates several neutrophil functions [50]. In cultured human MCs, IL-17A has been shown to activate different inflammatory pathways, mainly the canonical NF-κB pathway and its downstream cytokines, such as granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and growth-regulated alpha protein (GROα, also known as CXCL1), the latter involved in neutrophil infiltration into the peritoneum [74][75].

Besides its role in acute infections, Th17/IL-17A axis is also involved in chronic inflammation of the PM. In mice models of PDF exposure, a predominance of Th17 cells over Treg cells has been observed in the peritoneum [76], as well as activation of the transcription factors involved in Th17 differentiation retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (RORγt) and Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) [70]. Moreover, exposure to PDF induces local production of Th17-related cytokines (IL-17A and IL-6), together with a correlation between peritoneal IL-17A protein levels and membrane thickness [70]. In addition, studies conducted in gene mice deficient for CD69, a leucocyte protein that modulates Th17 cell differentiation, the chronic exposure to PDFs highly increased the Th17 response and IL-17A production leading to exacerbation of the inflammatory and fibroproliferative response [77][78]. In these PDF-exposure models, the treatment with neutralizing anti-IL-17A antibodies improved peritoneal damage [70][78]. Other study of PDF-exposure in uremic mice showed that conventional PDF treatment increased CD4+/IL-17+ cells in the peritoneal cavity [79], while a biocompatible low-GDP bicarbonate/lactate-based PDF increased peritoneal recruitment of M1 macrophages and decreased number of CD4+/IL-17+ cells, which were associated with better preservation of PM integrity [79]. These experimental studies support the detrimental effect of an enhanced Th17 response and IL-17A expression in the PDF-exposed peritoneum, whereas Th17 modulation and IL-17 targeting could be an effective therapeutic approach for peritoneal damage.

In peritoneal effluents from patients on PD using different conventional PDF, IL-17A has been found to increase, together with other cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) [80][81][82]. In peritoneal biopsies from PD patients, IL-17A-positive cells were found in the submesothelial zone overlapping with inflammatory and fibrosis areas. Interestingly, IL-17A levels in the effluents were significantly higher in long-term PD patients after 3 years of dialysis [70]. On the other hand, during peritonitis episodes IL-17A peritoneal effluents levels may reach a huge increase [83], showing the involvement of IL-17A in chronic and acute peritoneal damage.

Altogether, these pieces of evidence support the contribution of Th17 cells and IL-17A-producing cells to peritoneal inflammation associated with dialysis.

2.6. Other Cells Implicated in the Peritoneal Response to Infections: Mastocytes and Natural Killer Cells

The role of mastocytes, another resident leukocyte population, in peritoneal damage is controversial. A study performed in a mast cell-deficient rat model demonstrated that mast cells increase omental thickness and adhesion formation favoring leukocyte recruitment [84]. Studies performed in PD patients showed an increased number of mastocytes in samples from different inflammatory and fibrotic peritoneal diseases, including PD and encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) [85]. Studies in peritonitis demonstrated that natural killer (NK) cells have a role in neutrophil apoptosis and subsequent inflammation resolution [86][87]. For example, kidney dysfunction with induction of fibrosis and CKD progression correlates with activation of tubulointerstitial human CD56bright NK [88]. However, studies on humans are limited. NK cells in combination with IL-2 can cause peritoneal fibrosis in patients with malignancies [89].

3. Resident Peritoneal Cells: Activation of Proinflammatory and Immunomodulatory Signals

Peritoneum is composed of a monolayer of MCs with an epithelial-like cobblestone shape covering a continuum of the peritoneal cavity. Respect to its huge extension and its unique localization in the abdominal cavity, the peritoneum is a favorable site for the encounter of antigens and for the subsequent generation of the immune response. Resident MCs have a mesodermal origin, and their differentiation is controlled by the transcription factor Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1) [90][91]. MCs can undergo a process called mesothelial to mesenchymal Transition (MMT) in which they acquire mesenchymal features such as mobility and tissue invasion. The intrinsic plasticity of these cells is linked to their ability to acquire mesenchymal-like features in response to a variety of proinflammatory and profibrotic stimuli. Almost all the pro-inflammatory factors described in the previous section may promote the induction of MMT in MCs. This dedifferentiation process permits MCs to acquire morphological and functional features making these cells indistinguishable from myofibroblasts of other origin. High throughput experiments have correlated the expression of profibrotic and proinflammatory cytokines, such as TGFβ1, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), and IL-6 to the induction of MMT [24][92][93][94]. In fact, activated MCs are major producers of those cytokines, whose concentrations are elevated especially during peritonitis, and have been associated with ultrafiltration decline and protein loss [29][95]. The secretion of these cytokines impacts fibrosis, angiogenesis, and the inflammatory response.

The first phases of the peritoneal immune response not only involve resident peritoneal leucocytes [96][97]. MCs composing parietal and visceral peritoneum play an active role in the response to infections first directly responding to extracellular mediators released by microorganisms [98]. Human peritoneal MCs (HPMCs) express a specific subset of TLRs composed of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR3, with a moderate or scarce level of TLR4 and TLR10 [37]. A comparison of peritoneal MCs from murine and human origin responsiveness revealed important differences between the two species. The major difference consists of the unresponsiveness of HPMCs to TLR4 ligands, unlike murine peritoneal MCs (MPMCs). However, TLR4 is expressed by human MØ stably residing in the PM, and their response may contribute to inflammation leading to fibrosis [99][100]. Instead, HPMCs and MPMCs showed similarities in TLR1/2, TLR2/6 and TLR5 ligand responsiveness [99][100].

MCs are the main constituent of FALCs, whose frequency and size increase in the peritoneum of patients undergoing PD [101][102]. Besides MCs, FALCs are composed of MØs, and B1 cells. B1 cells have the potential to produce natural antibodies that provide a first protection against bacterial infections [103]. The chemokine CCL19 produced by structural components of FALCs is extremely relevant for monocyte recruitment during inflammation, activating a crosstalk that promotes T cell dependent-B cell immune response [104]. Thus, FALCs play a main role both in the regulation of polymorphonuclear (PMN) and mononuclear cell recruitment in the first phase of inflammation, as well as in the subsequent induction of the adaptive immunity.

Neutrophils, for example, use high endothelial venules present in FALCs to enter the peritoneal cavity, guided by the chemotactic signal of CXCL1 [44]. The production of CXCL1 as well as other chemoattractant CXCL8 by the peritoneal stroma is enhanced by inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and to a lesser extent, TNFα [105]. Stimulation of MCs with IL-1β or LPS, for example, also induces the production of a number of cytokines and chemokines including IL-6, TNFα, CCL2, CCL3, favoring mononuclear cell recruitment and activation [106].

Peritoneal mesothelium-derived chemokines have been recently proposed as potential therapeutic targets. In this sense, CXCL1 induced in MCs in response to IL-17 exposure displays angiogenic activity and can subsequently control the vascular remodeling in dialyzed peritoneum [107]. The observation of PD patients exhibiting high CXCL1 expression and subsequent density of microvessels opens to new intervening prospective acting to preserve long-term PM integrity and function.

Another important source of extracellular mediators engaged in peritoneal immunity are resident fibroblasts, embedded in the submesothelial stroma. Their role is mainly associated with the development of peritoneal fibrosis induced by chronic inflammation [108]. However, human peritoneal fibroblasts (HPFBs) upon stimulation with macrophage or T lymphocyte-derived proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNFα and IFN-γ, secrete large quantities of interleukins and chemokines (CCL2, IL-8/CXCL8, IL-6, CXCL1, CCL5) [105][109][110][111][112]. Therefore, HBFBs control trans-peritoneal chemotactic gradients during peritonitis, crucial when MCs are damaged and exfoliated.

References

- Ortiz, A.; Asociacion Informacion Enfermedades Renales Geneticas (AIRG-E); European Kidney Patients’ Federation (EKPF); Federación Nacional de Asociaciones para la Lucha Contra las Enfermedades del Riñón (ALCER); Fundación Renal Íñigo Álvarez de Toledo (FRIAT); Red de Investigación Renal (REDINREN); Resultados en Salud 2040 (RICORS2040); Sociedad Española de Nefrología (SENEFRO) Council; Sociedad Española de Trasplante (SET) Council; Organización Nacional de Trasplantes (ONT). RICORS2040: The need for collaborative research in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 372–387.

- Stevens, P.E.; Levin, A.; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group, M. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: Synopsis of the kidney disease: Improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 825–830.

- Ortiz, A.; Covic, A.; Fliser, D.; Fouque, D.; Goldsmith, D.; Kanbay, M.; Mallamaci, F.; Massy, Z.A.; Rossignol, P.; Vanholder, R.; et al. Epidemiology, contributors to, and clinical trials of mortality risk in chronic kidney failure. Lancet 2014, 383, 1831–1843.

- Council, E.-E.; Group, E.W. Chronic kidney disease is a key risk factor for severe COVID-19: A call to action by the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 87–94.

- Cheng, Y.; Luo, R.; Wang, K.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Dong, L.; Li, J.; Yao, Y.; Ge, S.; Xu, G. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 829–838.

- Corman, V.M.; Landt, O.; Kaiser, M.; Molenkamp, R.; Meijer, A.; Chu, D.K.; Bleicker, T.; Brunink, S.; Schneider, J.; Schmidt, M.L.; et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020, 25, 2000045.

- Thompson, R. Pandemic potential of 2019-nCoV. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 280.

- Bai, Y.; Yao, L.; Wei, T.; Tian, F.; Jin, D.Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, M. Presumed Asymptomatic Carrier Transmission of COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 323, 1406–1407.

- Chu, K.H.; Tsang, W.K.; Tang, C.S.; Lam, M.F.; Lai, F.M.; To, K.F.; Fung, K.S.; Tang, H.L.; Yan, W.W.; Chan, H.W.; et al. Acute renal impairment in coronavirus-associated severe acute respiratory syndrome. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 698–705.

- del Peso, G.; Jimenez-Heffernan, J.A.; Selgas, R.; Remon, C.; Ossorio, M.; Fernandez-Perpen, A.; Sanchez-Tomero, J.A.; Cirugeda, A.; de Sousa, E.; Sandoval, P.; et al. Biocompatible Dialysis Solutions Preserve Peritoneal Mesothelial Cell and Vessel Wall Integrity. A Case-Control Study on Human Biopsies. Perit. Dial. Int. 2016, 36, 129–134.

- Zhou, Q.; Bajo, M.A.; Del Peso, G.; Yu, X.; Selgas, R. Preventing peritoneal membrane fibrosis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 515–524.

- Devuyst, O.; Margetts, P.J.; Topley, N. The pathophysiology of the peritoneal membrane. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1077–1085.

- Bonomini, M.; Masola, V.; Procino, G.; Zammit, V.; Divino-Filho, J.C.; Arduini, A.; Gambaro, G. How to Improve the Biocompatibility of Peritoneal Dialysis Solutions (without Jeopardizing the Patient’s Health). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7955.

- Grantham, C.E.; Hull, K.L.; Graham-Brown, M.P.M.; March, D.S.; Burton, J.O. The Potential Cardiovascular Benefits of Low-Glucose Degradation Product, Biocompatible Peritoneal Dialysis Fluids: A Review of the Literature. Perit. Dial. Int. 2017, 37, 375–383.

- Kopytina, V.; Pascual-Antón, L.; Toggweiler, N.; Arriero-País, E.M.; Strahl, L.; Albar-Vizcaíno, P.; Sucunza, D.; Vaquero, J.J.; Steppan, S.; Piecha, D.; et al. Steviol glycosides as an alternative osmotic agent for peritoneal dialysis fluid. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 868374.

- Bazzato, G.; Coli, U.; Landini, S.; Fracasso, A.; Morachiello, P.; Righetto, F.; Scanferla, F.; Onesti, G. Xylitol as osmotic agent in CAPD: An alternative to glucose for uremic diabetic patients? Trans.–Am. Soc. Artif. Intern. Organs 1982, 28, 280–286.

- Rago, C.; Lombardi, T.; Di Fulvio, G.; Di Liberato, L.; Arduini, A.; Divino-Filho, J.C.; Bonomini, M. A New Peritoneal Dialysis Solution Containing L-Carnitine and Xylitol for Patients on Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis: First Clinical Experience. Toxins 2021, 13, 174.

- Wang, A.Y.; Brimble, K.S.; Brunier, G.; Holt, S.G.; Jha, V.; Johnson, D.W.; Kang, S.W.; Kooman, J.P.; Lambie, M.; McIntyre, C.; et al. ISPD Cardiovascular and Metabolic Guidelines in Adult Peritoneal Dialysis Patients Part II–Management of Various Cardiovascular Complications. Perit. Dial. Int. 2015, 35, 388–396.

- De Angelis, R.; Sant, M.; Coleman, M.P.; Francisci, S.; Baili, P.; Pierannunzio, D.; Trama, A.; Visser, O.; Brenner, H.; Ardanaz, E.; et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007 by country and age: Results of EUROCARE--5-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 23–34.

- Terri, M.; Trionfetti, F.; Montaldo, C.; Cordani, M.; Tripodi, M.; Lopez-Cabrera, M.; Strippoli, R. Mechanisms of Peritoneal Fibrosis: Focus on Immune Cells-Peritoneal Stroma Interactions. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 607204.

- Luo, Q.; Hu, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Gong, L.; Su, L.; Ren, B.; Ju, Y.; Jia, Z.; Dou, X. Enhanced mPGES-1 Contributes to PD-Related Peritoneal Fibrosis via Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 675363.

- Ludemann, W.M.; Heide, D.; Kihm, L.; Zeier, M.; Scheurich, P.; Schwenger, V.; Ranzinger, J. TNF Signaling in Peritoneal Mesothelial Cells: Pivotal Role of cFLIP(L). Perit. Dial. Int. 2017, 37, 250–258.

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Birnie, K.; Lansley, S.; Herrick, S.E.; Lim, C.B.; Prele, C.M. Mesothelial cells in tissue repair and fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 113.

- Raby, A.C.; Gonzalez-Mateo, G.T.; Williams, A.; Topley, N.; Fraser, D.; Lopez-Cabrera, M.; Labeta, M.O. Targeting Toll-like receptors with soluble Toll-like receptor 2 prevents peritoneal dialysis solution-induced fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2018, 94, 346–362.

- Karki, R.; Kanneganti, T.D. The ’cytokine storm’: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Trends Immunol. 2021, 42, 681–705.

- Thodis, E.; Passadakis, P.; Lyrantzopooulos, N.; Panagoutsos, S.; Vargemezis, V.; Oreopoulos, D. Peritoneal catheters and related infections. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2005, 37, 379–393.

- De Waele, J.; Lipman, J.; Sakr, Y.; Marshall, J.C.; Vanhems, P.; Barrera Groba, C.; Leone, M.; Vincent, J.L.; Investigators, E.I. Abdominal infections in the intensive care unit: Characteristics, treatment and determinants of outcome. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 420.

- Sartelli, M.; Catena, F.; Ansaloni, L.; Coccolini, F.; Corbella, D.; Moore, E.E.; Malangoni, M.; Velmahos, G.; Coimbra, R.; Koike, K.; et al. Complicated intra-abdominal infections worldwide: The definitive data of the CIAOW Study. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2014, 9, 37.

- Goodlad, C.; George, S.; Sandoval, S.; Mepham, S.; Parekh, G.; Eberl, M.; Topley, N.; Davenport, A. Measurement of innate immune response biomarkers in peritoneal dialysis effluent using a rapid diagnostic point-of-care device as a diagnostic indicator of peritonitis. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 1253–1259.

- Aufricht, C.; Beelen, R.; Eberl, M.; Fischbach, M.; Fraser, D.; Jorres, A.; Kratochwill, K.; LopezCabrera, M.; Rutherford, P.; Schmitt, C.P.; et al. Biomarker research to improve clinical outcomes of peritoneal dialysis: Consensus of the European Training and Research in Peritoneal Dialysis (EuTRiPD) network. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 824–835.

- Pauwels, S.; De Moor, B.; Stas, K.; Magerman, K.; Gyssens, I.C.; Van Ranst, M.; Cartuyvels, R. Coxsackievirus B1 peritonitis in a patient treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: A case report and brief review of the literature. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, E431–E434.

- Castro, R.; Abos, B.; Gonzalez, L.; Granja, A.G.; Tafalla, C. Expansion and differentiation of IgM(+) B cells in the rainbow trout peritoneal cavity in response to different antigens. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 70, 119–127.

- Miles, R.; Hawley, C.M.; McDonald, S.P.; Brown, F.G.; Rosman, J.B.; Wiggins, K.J.; Bannister, K.M.; Johnson, D.W. Predictors and outcomes of fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2009, 76, 622–628.

- Tomita, T.; Arai, S.; Kitada, K.; Mizuno, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Sakata, F.; Nakano, D.; Hiramoto, E.; Takei, Y.; Maruyama, S.; et al. Apoptosis inhibitor of macrophage ameliorates fungus-induced peritoneal injury model in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6450.

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 805–820.

- Roh, J.S.; Sohn, D.H. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Inflammatory Diseases. Immune. Netw. 2018, 18, e27.

- Colmont, C.S.; Raby, A.C.; Dioszeghy, V.; Lebouder, E.; Foster, T.L.; Jones, S.A.; Labeta, M.O.; Fielding, C.A.; Topley, N. Human peritoneal mesothelial cells respond to bacterial ligands through a specific subset of Toll-like receptors. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 4079–4090.

- van Aubel, R.A.; Keestra, A.M.; Krooshoop, D.J.; van Eden, W.; van Putten, J.P. Ligand-induced differential cross-regulation of Toll-like receptors 2, 4 and 5 in intestinal epithelial cells. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 44, 3702–3714.

- Gewirtz, A.T.; Navas, T.A.; Lyons, S.; Godowski, P.J.; Madara, J.L. Cutting edge: Bacterial flagellin activates basolaterally expressed TLR5 to induce epithelial proinflammatory gene expression. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 1882–1885.

- Wornle, M.; Sauter, M.; Kastenmuller, K.; Ribeiro, A.; Roeder, M.; Schmid, H.; Krotz, F.; Mussack, T.; Ladurner, R.; Sitter, T. Novel role of toll-like receptor 3, RIG-I and MDA5 in poly (I:C) RNA-induced mesothelial inflammation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2009, 322, 193–206.

- Merkle, M.; Ribeiro, A.; Sauter, M.; Ladurner, R.; Mussack, T.; Sitter, T.; Wornle, M. Effect of activation of viral receptors on the gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 in human mesothelial cells. Matrix. Biol. 2010, 29, 202–208.

- Zarember, K.A.; Godowski, P.J. Tissue expression of human Toll-like receptors and differential regulation of Toll-like receptor mRNAs in leukocytes in response to microbes, their products, and cytokines. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 554–561.

- Hurst, S.M.; Wilkinson, T.S.; McLoughlin, R.M.; Jones, S.; Horiuchi, S.; Yamamoto, N.; Rose-John, S.; Fuller, G.M.; Topley, N.; Jones, S.A. Il-6 and its soluble receptor orchestrate a temporal switch in the pattern of leukocyte recruitment seen during acute inflammation. Immunity 2001, 14, 705–714.

- Jackson-Jones, L.H.; Smith, P.; Portman, J.R.; Magalhaes, M.S.; Mylonas, K.J.; Vermeren, M.M.; Nixon, M.; Henderson, B.E.P.; Dobie, R.; Vermeren, S.; et al. Stromal Cells Covering Omental Fat-Associated Lymphoid Clusters Trigger Formation of Neutrophil Aggregates to Capture Peritoneal Contaminants. Immunity 2020, 52, 700–715.e6.

- Buechler, M.B.; Turley, S.J. Neutrophils Follow Stromal Omens to Limit Peritoneal Inflammation. Immunity 2020, 52, 578–580.

- Fielding, C.A.; McLoughlin, R.M.; McLeod, L.; Colmont, C.S.; Najdovska, M.; Grail, D.; Ernst, M.; Jones, S.A.; Topley, N.; Jenkins, B.J. IL-6 regulates neutrophil trafficking during acute inflammation via STAT3. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 2189–2195.

- Jones, S.A. Directing transition from innate to acquired immunity: Defining a role for IL-6. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 3463–3468.

- Tirado, M.; Koss, W. Differentiation of mesothelial cells into macrophage phagocytic cells in a patient with clinical sepsis. Blood 2018, 132, 1460.

- Wang, J.; Kubes, P. A Reservoir of Mature Cavity Macrophages that Can Rapidly Invade Visceral Organs to Affect Tissue Repair. Cell 2016, 165, 668–678.

- Catar, R.A.; Chen, L.; Cuff, S.M.; Kift-Morgan, A.; Eberl, M.; Kettritz, R.; Kamhieh-Milz, J.; Moll, G.; Li, Q.; Zhao, H.; et al. Control of neutrophil influx during peritonitis by transcriptional cross-regulation of chemokine CXCL1 by IL-17 and IFN-gamma. J. Pathol. 2020, 251, 175–186.

- Sica, A.; Erreni, M.; Allavena, P.; Porta, C. Macrophage polarization in pathology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 4111–4126.

- Wynn, T.A.; Vannella, K.M. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity 2016, 44, 450–462.

- Murray, P.J. Macrophage Polarization. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 541–566.

- Cassado Ados, A.; D’Imperio Lima, M.R.; Bortoluci, K.R. Revisiting mouse peritoneal macrophages: Heterogeneity, development, and function. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 225.

- Liao, C.T.; Andrews, R.; Wallace, L.E.; Khan, M.W.; Kift-Morgan, A.; Topley, N.; Fraser, D.J.; Taylor, P.R. Peritoneal macrophage heterogeneity is associated with different peritoneal dialysis outcomes. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1088–1103.

- Kubicka, U.; Olszewski, W.L.; Tarnowski, W.; Bielecki, K.; Ziolkowska, A.; Wierzbicki, Z. Normal human immune peritoneal cells: Subpopulations and functional characteristics. Scand. J. Immunol. 1996, 44, 157–163.

- Accarias, S.; Genthon, C.; Rengel, D.; Boullier, S.; Foucras, G.; Tabouret, G. Single-cell analysis reveals new subset markers of murine peritoneal macrophages and highlights macrophage dynamics upon Staphylococcus aureus peritonitis. Innate Immun. 2016, 22, 382–392.

- Barth, M.W.; Hendrzak, J.A.; Melnicoff, M.J.; Morahan, P.S. Review of the macrophage disappearance reaction. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1995, 57, 361–367.

- Hopkins, G.J.; Barter, P.J. Apolipoprotein A-I inhibits transformation of high density lipoprotein subpopulations during incubation of human plasma. Atherosclerosis 1989, 75, 73–82.

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Zhou, X.; Wan, M.; Lou, P.; Zhao, M.; Lv, K.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Peritoneal M2 macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles as natural multitarget nanotherapeutics to attenuate cytokine storms after severe infections. J. Control. Release 2022, 349, 118–132.

- Sutherland, T.E.; Shaw, T.N.; Lennon, R.; Herrick, S.E.; Ruckerl, D. Ongoing Exposure to Peritoneal Dialysis Fluid Alters Resident Peritoneal Macrophage Phenotype and Activation Propensity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 715209.

- Li, Q.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Shi, J.; Ni, J.; Wang, Q. A pathogenetic role for M1 macrophages in peritoneal dialysis-associated fibrosis. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 94, 131–139.

- Wang, J.; Jiang, Z.P.; Su, N.; Fan, J.J.; Ruan, Y.P.; Peng, W.X.; Li, Y.F.; Yu, X.Q. The role of peritoneal alternatively activated macrophages in the process of peritoneal fibrosis related to peritoneal dialysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 10369–10382.

- Chen, Y.T.; Hsu, H.; Lin, C.C.; Pan, S.Y.; Liu, S.Y.; Wu, C.F.; Tsai, P.Z.; Liao, C.T.; Cheng, H.T.; Chiang, W.C.; et al. Inflammatory macrophages switch to CCL17-expressing phenotype and promote peritoneal fibrosis. J. Pathol. 2020, 250, 55–66.

- de Fijter, C.W.; Verbrugh, H.A.; Peters, E.D.; Oe, P.L.; van der Meulen, J.; Verhoef, J.; Donker, A.J. In vivo exposure to the currently available peritoneal dialysis fluids decreases the function of peritoneal macrophages in CAPD. Clin. Nephrol. 1993, 39, 75–80.

- Fieren, M.W. Mechanisms regulating cytokine release from peritoneal macrophages during continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Blood Purif. 1996, 14, 179–187.

- Bellon, T.; Martinez, V.; Lucendo, B.; del Peso, G.; Castro, M.J.; Aroeira, L.S.; Rodriguez-Sanz, A.; Ossorio, M.; Sanchez-Villanueva, R.; Selgas, R.; et al. Alternative activation of macrophages in human peritoneum: Implications for peritoneal fibrosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 2995–3005.

- Kono, M. New insights into the metabolism of Th17 cells. Immunol. Med. 2023, 46, 15–24.

- Yasuda, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Hirota, K. The pathogenicity of Th17 cells in autoimmune diseases. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 283–297.

- Rodrigues-Diez, R.; Aroeira, L.S.; Orejudo, M.; Bajo, M.A.; Heffernan, J.J.; Rodrigues-Diez, R.R.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Ortiz, A.; Gonzalez-Mateo, G.; Lopez-Cabrera, M.; et al. IL-17A is a novel player in dialysis-induced peritoneal damage. Kidney Int. 2014, 86, 303–315.

- Chung, D.R.; Kasper, D.L.; Panzo, R.J.; Chitnis, T.; Grusby, M.J.; Sayegh, M.H.; Tzianabos, A.O. CD4+ T cells mediate abscess formation in intra-abdominal sepsis by an IL-17-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 1958–1963.

- Murphy, A.G.; O’Keeffe, K.M.; Lalor, S.J.; Maher, B.M.; Mills, K.H.; McLoughlin, R.M. Staphylococcus aureus infection of mice expands a population of memory gammadelta T cells that are protective against subsequent infection. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 3697–3708.

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lou, J.; Zhu, J.; He, M.; Deng, X.; Cai, Z. Neutralisation of peritoneal IL-17A markedly improves the prognosis of severe septic mice by decreasing neutrophil infiltration and proinflammatory cytokines. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46506.

- Witowski, J.; Ksiazek, K.; Warnecke, C.; Kuzlan, M.; Korybalska, K.; Tayama, H.; Wisniewska-Elnur, J.; Pawlaczyk, K.; Trominska, J.; Breborowicz, A.; et al. Role of mesothelial cell-derived granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in interleukin-17-induced neutrophil accumulation in the peritoneum. Kidney Int. 2007, 71, 514–525.

- Witowski, J.; Pawlaczyk, K.; Breborowicz, A.; Scheuren, A.; Kuzlan-Pawlaczyk, M.; Wisniewska, J.; Polubinska, A.; Friess, H.; Gahl, G.M.; Frei, U.; et al. IL-17 stimulates intraperitoneal neutrophil infiltration through the release of GRO alpha chemokine from mesothelial cells. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 5814–5821.

- Liappas, G.; Gonzalez-Mateo, G.T.; Majano, P.; Sanchez-Tomero, J.A.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Rodrigues Diez, R.; Martin, P.; Sanchez-Diaz, R.; Selgas, R.; Lopez-Cabrera, M.; et al. T Helper 17/Regulatory T Cell Balance and Experimental Models of Peritoneal Dialysis-Induced Damage. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 416480.

- Martin, P.; Gomez, M.; Lamana, A.; Cruz-Adalia, A.; Ramirez-Huesca, M.; Ursa, M.A.; Yanez-Mo, M.; Sanchez-Madrid, F. CD69 association with Jak3/Stat5 proteins regulates Th17 cell differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 4877–4889.

- Liappas, G.; Gonzalez-Mateo, G.T.; Sanchez-Diaz, R.; Lazcano, J.J.; Lasarte, S.; Matesanz-Marin, A.; Zur, R.; Ferrantelli, E.; Ramirez, L.G.; Aguilera, A.; et al. Immune-Regulatory Molecule CD69 Controls Peritoneal Fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 3561–3576.

- Vila Cuenca, M.; Keuning, E.D.; Talhout, W.; Paauw, N.J.; van Ittersum, F.J.; Ter Wee, P.M.; Beelen, R.H.J.; Vervloet, M.G.; Ferrantelli, E. Differences in peritoneal response after exposure to low-GDP bicarbonate/lactate-buffered dialysis solution compared to conventional dialysis solution in a uremic mouse model. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2018, 50, 1151–1161.

- Lee, C.T.; Ng, H.Y.; Hsu, C.Y.; Tsai, Y.C.; Yang, Y.K.; Chen, T.C.; Chiou, T.T.; Kuo, C.C.; Lee, W.C.; Hsu, K.T. Proinflammatory cytokines, hepatocyte growth factor and adipokines in peritoneal dialysis patients. Artif. Organs. 2010, 34, E222–E229.

- Parikova, A.; Zweers, M.M.; Struijk, D.G.; Krediet, R.T. Peritoneal effluent markers of inflammation in patients treated with icodextrin-based and glucose-based dialysis solutions. Adv. Perit. Dial. 2003, 19, 186–190.

- Sanz, A.B.; Aroeira, L.S.; Bellon, T.; del Peso, G.; Jimenez-Heffernan, J.; Santamaria, B.; Sanchez-Nino, M.D.; Blanco-Colio, L.M.; Lopez-Cabrera, M.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; et al. TWEAK promotes peritoneal inflammation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90399.

- Lin, C.Y.; Roberts, G.W.; Kift-Morgan, A.; Donovan, K.L.; Topley, N.; Eberl, M. Pathogen-specific local immune fingerprints diagnose bacterial infection in peritoneal dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013, 24, 2002–2009.

- Zareie, M.; Fabbrini, P.; Hekking, L.H.; Keuning, E.D.; Ter Wee, P.M.; Beelen, R.H.; van den Born, J. Novel role for mast cells in omental tissue remodeling and cell recruitment in experimental peritoneal dialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 3447–3457.

- Alscher, D.M.; Braun, N.; Biegger, D.; Fritz, P. Peritoneal mast cells in peritoneal dialysis patients, particularly in encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2007, 49, 452–461.

- Anuforo, O.U.U.; Bjarnarson, S.P.; Jonasdottir, H.S.; Giera, M.; Hardardottir, I.; Freysdottir, J. Natural killer cells play an essential role in resolution of antigen-induced inflammation in mice. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 93, 1–8.

- Thoren, F.B.; Riise, R.E.; Ousback, J.; Della Chiesa, M.; Alsterholm, M.; Marcenaro, E.; Pesce, S.; Prato, C.; Cantoni, C.; Bylund, J.; et al. Human NK Cells induce neutrophil apoptosis via an NKp46- and Fas-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 1668–1674.

- Law, B.M.P.; Wilkinson, R.; Wang, X.; Kildey, K.; Lindner, M.; Rist, M.J.; Beagley, K.; Healy, H.; Kassianos, A.J. Interferon-gamma production by tubulointerstitial human CD56(bright) natural killer cells contributes to renal fibrosis and chronic kidney disease progression. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 79–88.

- Steis, R.G.; Urba, W.J.; VanderMolen, L.A.; Bookman, M.A.; Smith, J.W., 2nd; Clark, J.W.; Miller, R.L.; Crum, E.D.; Beckner, S.K.; McKnight, J.E.; et al. Intraperitoneal lymphokine-activated killer-cell and interleukin-2 therapy for malignancies limited to the peritoneal cavity. J. Clin. Oncol. 1990, 8, 1618–1629.

- Gulyas, M.; Hjerpe, A. Proteoglycans and WT1 as markers for distinguishing adenocarcinoma, epithelioid mesothelioma, and benign mesothelium. J. Pathol. 2003, 199, 479–487.

- Wilm, B.; Munoz-Chapuli, R. The Role of WT1 in Embryonic Development and Normal Organ Homeostasis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1467, 23–39.

- Strippoli, R.; Sandoval, P.; Moreno-Vicente, R.; Rossi, L.; Battistelli, C.; Terri, M.; Pascual-Anton, L.; Loureiro, M.; Matteini, F.; Calvo, E.; et al. Caveolin1 and YAP drive mechanically induced mesothelial to mesenchymal transition and fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 647.

- Namvar, S.; Woolf, A.S.; Zeef, L.A.; Wilm, T.; Wilm, B.; Herrick, S.E. Functional molecules in mesothelial-to-mesenchymal transition revealed by transcriptome analyses. J. Pathol. 2018, 245, 491–501.

- Ruiz-Carpio, V.; Sandoval, P.; Aguilera, A.; Albar-Vizcaino, P.; Perez-Lozano, M.L.; Gonzalez-Mateo, G.T.; Acuna-Ruiz, A.; Garcia-Cantalejo, J.; Botias, P.; Bajo, M.A.; et al. Genomic reprograming analysis of the Mesothelial to Mesenchymal Transition identifies biomarkers in peritoneal dialysis patients. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44941.

- Lambie, M.; Chess, J.; Donovan, K.L.; Kim, Y.L.; Do, J.Y.; Lee, H.B.; Noh, H.; Williams, P.F.; Williams, A.J.; Davison, S.; et al. Independent effects of systemic and peritoneal inflammation on peritoneal dialysis survival. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 2071–2080.

- Roberts, G.W.; Baird, D.; Gallagher, K.; Jones, R.E.; Pepper, C.J.; Williams, J.D.; Topley, N. Functional effector memory T cells enrich the peritoneal cavity of patients treated with peritoneal dialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1895–1900.

- Cailhier, J.F.; Partolina, M.; Vuthoori, S.; Wu, S.; Ko, K.; Watson, S.; Savill, J.; Hughes, J.; Lang, R.A. Conditional macrophage ablation demonstrates that resident macrophages initiate acute peritoneal inflammation. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 2336–2342.

- Yung, S.; Chan, T.M. Intrinsic cells: Mesothelial cells -- central players in regulating inflammation and resolution. Perit. Dial. Int. 2009, 29, S21–S27.

- Park, J.H.; Kim, Y.G.; Shaw, M.; Kanneganti, T.D.; Fujimoto, Y.; Fukase, K.; Inohara, N.; Nunez, G. Nod1/RICK and TLR signaling regulate chemokine and antimicrobial innate immune responses in mesothelial cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 514–521.

- Kato, S.; Yuzawa, Y.; Tsuboi, N.; Maruyama, S.; Morita, Y.; Matsuguchi, T.; Matsuo, S. Endotoxin-induced chemokine expression in murine peritoneal mesothelial cells: The role of toll-like receptor 4. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 1289–1299.

- Beelen, R.H.; Oosterling, S.J.; van Egmond, M.; van den Born, J.; Zareie, M. Omental milky spots in peritoneal pathophysiology (spots before your eyes). Perit. Dial. Int. 2005, 25, 30–32.

- Rangel-Moreno, J.; Moyron-Quiroz, J.E.; Carragher, D.M.; Kusser, K.; Hartson, L.; Moquin, A.; Randall, T.D. Omental milky spots develop in the absence of lymphoid tissue-inducer cells and support B and T cell responses to peritoneal antigens. Immunity 2009, 30, 731–743.

- Mebius, R.E. Lymphoid organs for peritoneal cavity immune response: Milky spots. Immunity 2009, 30, 670–672.

- Perez-Shibayama, C.; Gil-Cruz, C.; Cheng, H.W.; Onder, L.; Printz, A.; Morbe, U.; Novkovic, M.; Li, C.; Lopez-Macias, C.; Buechler, M.B.; et al. Fibroblastic reticular cells initiate immune responses in visceral adipose tissues and secure peritoneal immunity. Sci. Immunol. 2018, 3, 26.

- Witowski, J.; Tayama, H.; Ksiazek, K.; Wanic-Kossowska, M.; Bender, T.O.; Jorres, A. Human peritoneal fibroblasts are a potent source of neutrophil-targeting cytokines: A key role of IL-1beta stimulation. Lab. Investig. 2009, 89, 414–424.

- Riese, J.; Denzel, C.; Zowe, M.; Mehler, C.; Hohenberger, W.; Haupt, W. Secretion of IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha, and TNFalpha by cultured intact human peritoneum. Eur. Surg. Res. 1999, 31, 281–288.

- Catar, R.A.; Bartosova, M.; Kawka, E.; Chen, L.; Marinovic, I.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, H.; Wu, D.; Zickler, D.; Stadnik, H.; et al. Angiogenic Role of Mesothelium-Derived Chemokine CXCL1 During Unfavorable Peritoneal Tissue Remodeling in Patients Receiving Peritoneal Dialysis as Renal Replacement Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 821681.

- Margetts, P.J.; Bonniaud, P. Basic mechanisms and clinical implications of peritoneal fibrosis. Perit. Dial. Int. 2003, 23, 530–541.

- Jorres, A.; Ludat, K.; Lang, J.; Sander, K.; Gahl, G.M.; Frei, U.; DeJonge, K.; Williams, J.D.; Topley, N. Establishment and functional characterization of human peritoneal fibroblasts in culture: Regulation of interleukin-6 production by proinflammatory cytokines. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1996, 7, 2192–2201.

- Witowski, J.; Thiel, A.; Dechend, R.; Dunkel, K.; Fouquet, N.; Bender, T.O.; Langrehr, J.M.; Gahl, G.M.; Frei, U.; Jorres, A. Synthesis of C-X-C and C-C chemokines by human peritoneal fibroblasts: Induction by macrophage-derived cytokines. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 158, 1441–1450.

- Witowski, J.; Kawka, E.; Rudolf, A.; Jorres, A. New developments in peritoneal fibroblast biology: Implications for inflammation and fibrosis in peritoneal dialysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 134708.

- Kawka, E.; Witowski, J.; Fouqet, N.; Tayama, H.; Bender, T.O.; Catar, R.; Dragun, D.; Jorres, A. Regulation of chemokine CCL5 synthesis in human peritoneal fibroblasts: A key role of IFN-gamma. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 590654.

More

Information

Subjects:

Urology & Nephrology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

765

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

29 Mar 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No