Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ahmed Esmael | -- | 2927 | 2023-03-23 17:33:20 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2927 | 2023-03-24 02:32:41 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Esmael, A.; Al-Hindi, R.R.; Albiheyri, R.S.; Alharbi, M.G.; Filimban, A.A.R.; Alseghayer, M.S.; Almaneea, A.M.; Alhadlaq, M.A.; Ayubu, J.; Teklemariam, A.D. Pathogenic Bacteria and Fresh Produce. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42489 (accessed on 01 March 2026).

Esmael A, Al-Hindi RR, Albiheyri RS, Alharbi MG, Filimban AAR, Alseghayer MS, et al. Pathogenic Bacteria and Fresh Produce. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42489. Accessed March 01, 2026.

Esmael, Ahmed, Rashad R. Al-Hindi, Raed S. Albiheyri, Mona G. Alharbi, Amani A. R. Filimban, Mazen S. Alseghayer, Abdulaziz M. Almaneea, Meshari Ahmed Alhadlaq, Jumaa Ayubu, Addisu D. Teklemariam. "Pathogenic Bacteria and Fresh Produce" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42489 (accessed March 01, 2026).

Esmael, A., Al-Hindi, R.R., Albiheyri, R.S., Alharbi, M.G., Filimban, A.A.R., Alseghayer, M.S., Almaneea, A.M., Alhadlaq, M.A., Ayubu, J., & Teklemariam, A.D. (2023, March 23). Pathogenic Bacteria and Fresh Produce. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42489

Esmael, Ahmed, et al. "Pathogenic Bacteria and Fresh Produce." Encyclopedia. Web. 23 March, 2023.

Copy Citation

The consumer demand for fresh produce (vegetables and fruits) has considerably increased since the 1980s for more nutritious foods and healthier life practices, particularly in developed countries. Several foodborne outbreaks have been linked to fresh produce. The global rise in fresh produce associated with human infections may be due to the use of wastewater or any contaminated water for the cultivation of fruits and vegetables, the firm attachment of the foodborne pathogens on the plant surface, and the internalization of these agents deep inside the tissue of the plant, poor disinfection practices and human consumption of raw fresh produce.

fresh produce

foodborne bacteria

stomata

1. Introduction

Fresh produce (vegetables and fruits) consumption has increased considerably since the 1980s because of the increasing consumer demand for a healthy life, particularly in developed countries. Following FAO guidelines, 400 g of fresh fruits and vegetables should be consumed daily [1]. Fresh produce diets have been shown to protect humans from some chronic ailments including cancer, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases [1].

Fresh produce is one of the crucial constituents of healthy food; nevertheless, they have been linked with several seasonal or global foodborne outbreaks, causing illnesses and serious economic losses. It has been estimated that nearly 76 million cases of foodborne diseases occur yearly in the United States [2]. Salmonella enterica (e.g., S. enterica serovar Typhimurium) and Escherichia coli (e.g., E. coli O157:H7) appear to be the most prevalent causative agents of foodborne infection linked to the ingestion of fresh produce [2]. These human pathogens are not known to be plant pathogens. Human microbial pathogens (HMPs) colonize and firmly attach to the plant surface or internalize into the plant tissues and sustain their population in the mesophyll without causing infection in the plant. Several laboratories’ microscopic-based investigations have shown the association of HMPs, particularly E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella spp., with plant stomata, wounds, and lesions found on the leaf of the plant [3]. These HMPs are not easily removed or decontaminated with standard disinfection procedures [4].

During the last few years, the prevalence, incidence, severity, and spreading of human diseases associated with the ingestion of fresh green products have drawn the focus of farmers, food industry, consumers, researchers, and politicians [5]. According to the CDC report during the period between 1998 to 2013, 972 green raw products-associated outbreaks were reported causing 34,674 diseases, 2315 hospitalizations, and 72 mortalities in the U.S. [6]. Most of these diseases were caused by E. coli (10%), Salmonella enterica (21%), and norovirus (54% of outbreaks) [6]. This is attributed to the increased promotion and trend of consuming fresh green products. Lettuce (salad leaves) consumption has considerably increased (12.0 kg/person/year) in the U.S. during the past decade [7]. Additionally, in the U.S. the annual demand for packed salads has increased over the last two decades [8], which implies there was a real change in the consumers’ attitude towards buying slightly treated salads and/or ready-to-eat foods.

Fresh green products are vulnerable to pathogenic contamination during storage, production, packaging, processing, and transportation [9][10]. During the production of vegetables, the main vehicles for bacterial contamination are farm and municipal waste, manure soil amendments, irrigation water, and intrusion of wild animals [11][12][13]. For effective leafy green colonization, bacteria entail the capacity to adhere, internalize, and/or create biofilms to withstand exterior or interior disturbance and survive epiphytically. Both E. coli and Salmonella can modulate their cellular function upon the contact of leaf greens towards the generation of biomolecules that participated in attachment and biofilm formation [14]. Phylloplane settlement progressions are mostly accompanied by the internalization of the bacterial agent through the stomatal openings. Studies have displayed that the two most common leafy green contaminants, E. coli and Salmonella, can reach the intercellular regions of the leaf via the stomatal aperture [15][16][17][18]. Human bacteria could recognize plant cells through Microbe-Associated Molecular Patterns (MAMPs) to initiate defense responses associated with Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI) [19], including a diminution of the width of stomatal openings [18][20]. In contrast, bacteria could destabilize the stomatal closure defense to deal with such responses [18] or activate the expression of genes linked to antimicrobial resistance and oxidative stress tolerance [21].

The impact of plants and human bacterial pathogen interactions on the leaf is profoundly affected by agents’ persistence time in/on leafy greens [22][23]. The viability of bacterial pathogens in the phyllosphere is mostly reliant on the species of the plant and their genotypes [24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31]. Intra- and inter-specific variations of certain leafy traits have resulted in a variation in bacterial colonization. Research findings indicated that varying E. coli O157:H7 persistence on spinach leaves has been affected by the roughness of the leaf blade and the density of the stomata. Other factors associated with the surface of the leaf, including hydrophobicity, level of epicuticular wax, and vein density, were linked to cultivar-specific differences in S. enterica ser. Senftenberg attachment on Batavia type lettuces and iceberg [28]. In tomatoes, the genotype of the plant influenced S. enterica persistence in the phyllosphere after the dip-inoculation with a cocktail of eight-serovars (Mbandaka, Baildon, Cubana, Enteritidis, Newport, Havana, Schwarzengrund, and Poona) [24]. In addition, the colonization of lettuce and tomato seedlings by S. enterica could be affected by the plant species, cultivar, bacterial strains, and serovar [32]. In general, plant–HMPs interaction is a complex science that involves several factors from different perspectives.

Safe production methods and proper decontamination or disinfection procedures are critical steps in ensuring the food safety of ready-to-eat foods and fresh produces. Most of fresh produce is eaten raw or minimally processed and does not undergo a ‘lethal’ process treatment, such as cooking. In addition, disinfection and cleaning are very important processes during food processing and packaging to ensure hygienic products and food safety [33]. The efficacy of various disinfectants and sanitizing methods for reducing the burden of microbial populations on raw fruits and vegetables varies greatly. Differences in the characteristics of the surface of the fresh produce, type and physiological state of microbial cells, the method and procedure used for disinfection (e.g., temperature, contact time, pH, dosage, residual concentration, etc.), and environmental stress conditions interact to influence the activity of disinfectants and sanitizers [34]. Vigorously washing vegetables and fruits with clean water minimizes the number of microorganisms by 10–100-fold and is often as effective as treatment with 200 ppm chlorine. To date, several types of physical and chemical methods are used for the decontamination of fresh produce to prevent the infection of humans with pathogenic microorganisms [35]. Most of the commercial methods are based on chemical principles, including chlorine dioxide (ClO2), ozone (O3), peracetic acid, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), edible coatings, cold plasma, and so on [33]. Physical non-thermal decontamination methods are effective at sub-lethal temperatures, thus it minimize negative consequences on the nutritional value of food [36]. These include the application of power ultrasound, gamma irradiation, UV treatment, high hydrostatic pressure, beta irradiation, and pulsed light. They are efficient but applicable to certain types of food matrices and use more time and energy. Purely physical procedures, such as high hydrostatic pressure, are chemically secure, but they necessitate complicated and costly equipment [37], and this can affect the quality of food products [38].

2. Factors Affecting the Interaction between Pathogenic Bacteria and Fresh Produce

2.1. Factor Associated with Bacteriological Agents

The interaction between HMPs and fresh produce depends on different factors, and one of these factors are linked with the pathogen by itself. HMPs population size [39], bacteria species or strain involved [40], and the presence of bacterial cell surface appendages like pili/fimbriae, curli, flagella, and cellulose. Bacterial biofilm is also another factor that determines the plant–pathogen interaction [14].

2.1.1. Biofilm

A biofilm is one of the most effective mechanisms used by HMPs to generate evasive fitness against immunologically challenging environments on or inside plants. Microbial biofilms can form on the surfaces of leaves and roots, as well as within plant tissues’ intercellular spaces. Biofilms protect bacteria from desiccation, UV radiation, environmental stress, and defense immunity of plants. They also protect against antimicrobial agents produced by normal flora or by the plant itself. A microbial biofilm also generates a protective coat against disinfectants and antiseptics used during food processing [41]. A biofilm is a mechanism by which HMPs survive in a nutrient-poor microenvironment inside or on the plant surface.

2.1.2. Bacterial Curli

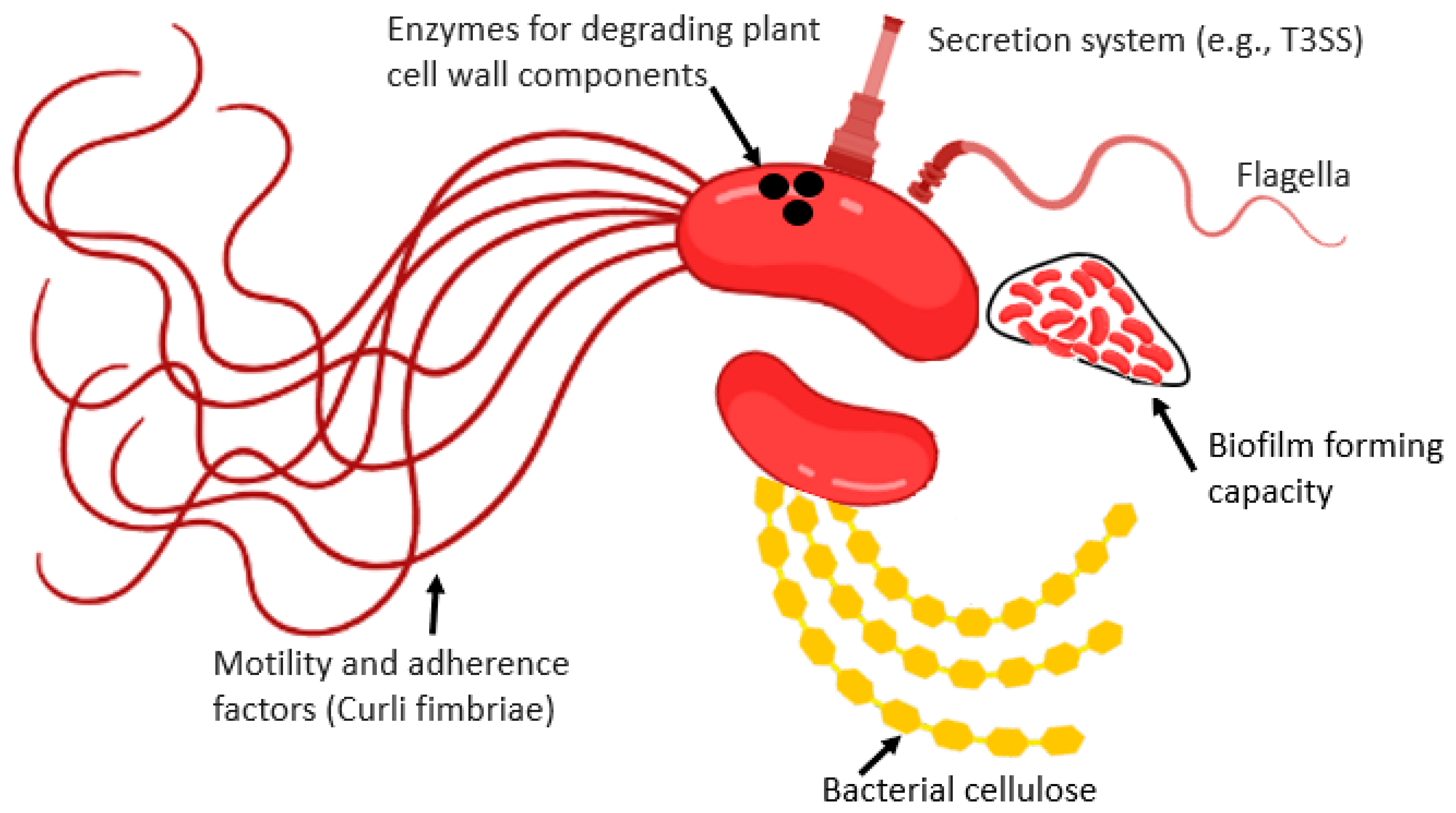

Curli are the main proteinaceous constituent of extra-cellular matrix synthesized by many enterobacterial pathogens. Curli fibers participate in cell aggregation, attachment to the plant surfaces, and biofilm formation. Curli are also involved in host cell attachment and invasion, and they are crucial inducers of the plant immune response (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Some of the bacteriological factors which determine the internalization of HMPs inside the plant tissue.

2.1.3. Flagella

Flagella are motility organelles, which facilitate reaching favorable habitats and serve as adhesive material to enhance their capability to attach to plant surfaces (Figure 1). The bacteriological agents adhere and irreversibly attach to the plant surface to develop microcolonies. They secrete EPS for the interactions between cells and plant surfaces. They also develop complex biofilm structures by interacting with alternative matrix components.

2.1.4. Cellulose and Pili/Fimbriae

The extracellular matrix, cellulose is crucial for the attachment of Salmonella. A lower level of colonization was noted in bcsA (cellulose synthase) lacking S. enterica Enteritidis mutant in alfalfa sprouts as compared to wild type. However, normal colonization capability was achieved after the plasmid-based bcsA expression [42].

Adhesins containing hair-like Pili/fimbriae (P, 1, F1C, and S in E. coli) are present on the bacterial cell surface that exhibit affinity to various carbohydrates. The interaction of adhesins with mammal components is either non-specific (electrostatic or hydrophobic) or specific (binding with specific host cell receptor moieties), which carries out tropism for the adhesion with specific tissue or host [43]. Salmonella and E. coli adhesins and fimbriae (amyloid curli fimbriae) have been studied concerning their plant adhesions. Curli is known to facilitate the Salmonella and E. coli attachments to leaves and sprouts, but their inactivation effect is low.

2.2. Plant Factors

The colonization and interaction of foodborne pathogens (e.g., Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli) with the plant immune system have been documented in various studies [19]. Plant factors include attachment sites [44], properties of plant surfaces [45], plant nutritive constituents and growing conditions [46][47], development stage [16][48], plant’s cultivar [24][26], and contamination site [49]. In some situations, like the case of STEC, the rate of internalization is dependent on multiple factors, including the plant species and tissue [50] and how plants are propagated [51].

2.2.1. Properties of Plant Surfaces

Most of the aerial surfaces of the plants are covered with a hydrophobic cuticle that is mainly composed of polysaccharides, waxes, and fatty acids. It favors the attachment of hydrophobic molecules, whereas hydrophilic structures become exposed at the breaking points in the cuticle [45]. This situation helps the bacteria on the root surface to enter the plant cells generally covered with polysaccharides (pectin and cellulose) and glycoproteins. Such molecules are hydrophilic and can be negatively charged in some cases [52]. The attachment strength is correlated with the charge on the plant surface [53]. However, the exact binding sites or receptors remain unknown. The study of S. Typhimurium’s attachment to potato slices has revealed bacterial attachment to cell wall junctions. Bacteria were particularly noted to attach with the pectin layer at the cell wall junctions that could be the bacterial binding site [54]. Contrarily, another study has demonstrated a reduced Salmonella attachment to the components of the cell wall mainly containing pectin. Therefore, it could be deduced that pectin is less favorable for bacterial attachment than cellulose [55].

Plant surface architecture and topography are crucial for microbial adhesion. Similarly, roughness is also important for bacterial survival and adherence to plant tissues. E. coli O157:H7 adhesion to the leaves of various spinach cultivars has been investigated [27]. Plant leaves’ surface roughness depends on the leaf age and plant nature. During a study, high Salmonella affinity was noted for the old artificially contaminated leaves as compared to young lettuce leaves. A higher S. Typhimurium localization near the petiole has been noted. Similarly, a high bacterial affinity to the abaxial leaf side was observed as compared to the adaxial side [25]. Cantaloupe netting fissures are favorable Salmonella attachment sites, which help in their survival against sanitizers [56].

2.2.2. Nutrient Content and Its Location in the Plant Tissue

Microflora distribution on the leaf surface is not homogenous and bacterial cells prefer to colonize at specific sites on the leaf surface, such as stomata, trichomes base, junctions of the epidermal cell wall, grooves or depressions near veins, and beneath the cuticle [57]. These points are rich in nutrients and water and protect bacteria from stress. Plant appendages (secretory ducts or cavities) could release metabolites. Glandular trichomes outgrow from the epidermis and act as an accumulation and secretion site for various compounds including defensive proteins, Pb ions, Ca, Mn, Na, and secondary metabolites (phenylpropanoids, monoterpenoids, and essential oils). Bacterial presence on the lower leaf surface is generally higher than on the upper surface. This might be due to low radiation, a thin layer of cuticle, and high trichomes and stomata density [44]. Therefore, the conditions are much better for the growth and survival of bacteria at the lower surface of the leaf as compared to other leaf parts.

Most human pathogenic bacterial strains, including STEC, preferentially colonize the roots and rhizosphere of fresh produce plants over leafy tissue and are internalized by plant tissue, where they can persist in the apoplastic space as an endophyte [49]. The apoplast contains metabolites, such as solutes, sugars, proteins, and cell wall components [49], and as such, it provides a rich environment for many bacterial species, including both commensal bacteria and human pathogens [49].

Similar behavior of human enteric pathogens has been documented on leaves with minor differences. Salmonella enterica serovar Thompson could attach in the cell margins and around the stomata of spinach leaves where the presence of native bacteria is detected [58]. The confocal microscopy of E. coli attachment at trichomes and stomata of cut lettuce plants revealed its attachment similarity with plant pathogens [15]. The stomata serve as protective bacterial niches and nutrient sources. Golberg and colleagues [25] confirmed the preference of this niche by Salmonella cells by demonstrating their high localization within and near lettuce leaves stomata. However, Salmonella colonization around stomata is limited to only a few serovars on specific plants. Contrarily, E. coli could better attach to cut lettuce surfaces, whereas Pseudomonas fluorescens prefers to attach on intact surfaces. However, S. Typhimurium could attach to both intact and cut surfaces [59]. The localization capability of enteric pathogens at similar leaf adhesion sites with plant pathogens and natural microflora helps in their long-term survival.

Enteric bacteria penetrate the soil through fertilizers, water, or directly through roots during hydroponic growth to attach to the host plant rhizosphere. Then, they invade and move to upper plant parts [60]. In contrast to fruits and leaves, the location of these bacterial attachments was significantly different than natural microflora. Natural plant pathogens and microflora generally attach to the trichome root hairs and epidermis. Plant pathogens could rapidly bind at the wound sites and cut ends of roots, whereas their binding at root tips is poor [61]. Contrarily, E. coli strains preferably attached at alfalfa sprouts root tip, but their attachment to the roots was quite slow. However, not all the studied E. coli strains bind to root hairs [62].

2.2.3. Decontamination Methods Employed

E. coli and Salmonella attachment is considered an active step; however, this assumption is not supported by all the studies. In one study, for instance, only Salmonella viable cells could attach to potato slices [54]. Contrarily, the attachment levels of killed E. coli O157:H7, live E. coli O157:H7, and fluorescent polystyrene microspheres remained similar [63]. The differential results could be associated with the varying methods of bacterial inactivation. Glutaraldehyde was used to inactivate the E. coli cells, which could potentially change the bacterial adhesive features whereas various methods (thermal, ethanol, formalin, and kanamycin) were adopted to inactivate Salmonella cells [54]. Fresh produce-related pathogens are difficult to wash with antimicrobial and chlorine solutions [64]. Several studies have reported that chemicals-based washing of production-associated pathogens could be achieved from 1 (minimum) to 3 logs (maximum) [12][65]. Recently, less susceptibility to enteric pathogens has been reported against common sanitizers (chlorine) as compared to indigenous microorganisms. It suggests that the pathogens remaining after sanitizing could survive and grow on wet products with comparatively less competition [65].

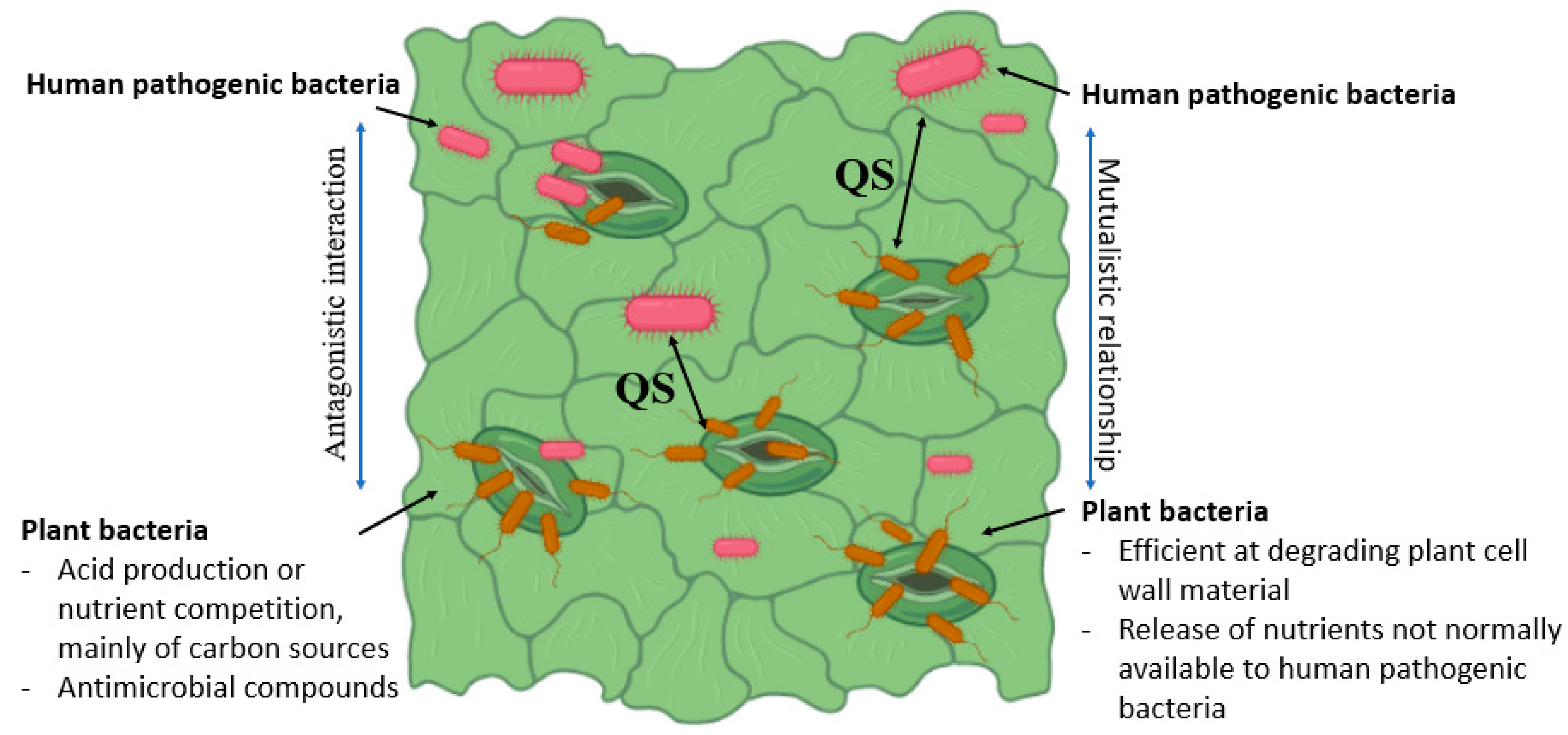

2.2.4. Plant Microbial Flora and Bacteria-to-Bacteria Interactions

Plant microbiota could inhibit or promote enteric pathogens’ establishment in plants (Figure 2). Plant diseases affect the phyllosphere atmosphere to promote the growth of the enteric pathogen. Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. Carotovorum co-inoculation with E. coli O157:H7 or S. enterica increased their levels by more than 10-fold in comparison to individual inoculations [66]. Resident bacteria (Erwinia herbicola and P. syringae) and plant pathogens could enhance the S. enterica survival on leaves. An S. enterica viable population on plants pre-inoculated with one of two E. herbicola strains and P. syringae was increased by 10-fold compared to controls [67]. Salmonella protection from desiccation by plant epiphytic bacteria on leaf surfaces has been reported. Recently, Potnis et al. have revealed pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity suppression by a virulent strain X. perforans. X. perforans generate an S. enterica-friendly environment by inducing effector-triggered susceptibility in tomato phyllosphere. However, the S. enterica population was reduced by an avirulent strain of X. perforans, which activated the effector-triggered immunity [68]. Several investigations have reported that the presence of other microbes helps in enteric pathogen colonization in leaf environment. However, a reduction in soft rot progression and P. carotovorum subsp. carotovorum population was noted in the presence of S. enterica (enteric pathogen), which moderated the pH of the local environment [69].

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of plant and HMPs intracellular interaction within the plant tissue. Bacterial communication occurs via small signaling molecules called quorum sensing (QS) factors, which are involved in the activation of virulence genes and the formation of biofilms and related immunological barriers.

References

- The International Year of Fruits and Vegetables. 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fruits-vegetables-2021/en/ (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Carstens, C.K.; Salazar, J.K.; Darkoh, C. Multistate outbreaks of foodborne illness in the United States associated with fresh produce from 2010 to 2017. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2667.

- de Oliveira Elias, S.; Noronha, T.B.; Tondo, E.C. Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli O157: H7 prevalence and levels on lettuce: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Microbiol. 2019, 84, 103217.

- van Dijk, H.F.G.; Verbrugh, H.A.; Ad Hoc Advisory Committee on Disinfectants of the Health Council of the Netherlands. Resisting disinfectants. Commun. Med. 2022, 2, 6.

- Rahman, M.; Alam, M.-U.; Luies, S.K.; Kamal, A.; Ferdous, S.; Lin, A.; Sharior, F.; Khan, R.; Rahman, Z.; Parvez, S.M. Contamination of fresh produce with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and associated risks to human health: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 360.

- Bennett, S.; Sodha, S.; Ayers, T.; Lynch, M.; Gould, L.; Tauxe, R. Produce-associated foodborne disease outbreaks, USA, 1998–2013. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 146, 1397–1406.

- USDA. Vegetables and Pulses Yearbook Tables. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/vegetables-and-pulses-data/vegetables-and-pulses-yearbook-tables/ (accessed on 11 April 2019).

- Available online: https://arefiles.ucdavis.edu/uploads/filer_public/fb/7b/fb7b6380-cdf9-4db5-b5d2-993640bcc1e6/freshcut2016cook20160926final.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2016).

- Barak, J.D.; Schroeder, B.K. Interrelationships of food safety and plant pathology: The life cycle of human pathogens on plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2012, 50, 241–266.

- Sapers, G.M.; Doyle, M.P. Scope of the produce contamination problem. In The Produce Contamination Problem; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3–20.

- Jay-Russell, M.T. What is the risk from wild animals in food-borne pathogen contamination of plants? CABI Rev. 2014, 1–16.

- Allende, A.; Monaghan, J. Irrigation water quality for leafy crops: A perspective of risks and potential solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 7457–7477.

- Jiang, X.; Chen, Z.; Dharmasena, M. The role of animal manure in the contamination of fresh food. In Advances in Microbial Food Safety; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 312–350.

- Yaron, S.; Römling, U. Biofilm formation by enteric pathogens and its role in plant colonization and persistence. Microb. Biotechnol. 2014, 7, 496–516.

- Seo, K.; Frank, J. Attachment of Escherichia coli O157: H7 to lettuce leaf surface and bacterial viability in response to chlorine treatment as demonstrated by using confocal scanning laser microscopy. J. Food Prot. 1999, 62, 3–9.

- Kroupitski, Y.; Golberg, D.; Belausov, E.; Pinto, R.; Swartzberg, D.; Granot, D.; Sela, S. Internalization of Salmonella enterica in leaves is induced by light and involves chemotaxis and penetration through open stomata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 6076–6086.

- Saldaña, Z.; Sánchez, E.; Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Puente, J.L.; Girón, J.A. Surface structures involved in plant stomata and leaf colonization by Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli O157: H7. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 119.

- Roy, D.; Panchal, S.; Rosa, B.A.; Melotto, M. Escherichia coli O157: H7 induces stronger plant immunity than Salmonella enterica Typhimurium SL1344. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 326–332.

- Garcia, A.V.; Charrier, A.; Schikora, A.; Bigeard, J.; Pateyron, S.; de Tauzia-Moreau, M.-L.; Evrard, A.; Mithöfer, A.; Martin-Magniette, M.L.; Virlogeux-Payant, I. Salmonella enterica flagellin is recognized via FLS2 and activates PAMP-triggered immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 2014, 7, 657–674.

- Melotto, M.; Underwood, W.; Koczan, J.; Nomura, K.; He, S.Y. Plant stomata function in innate immunity against bacterial invasion. Cell 2006, 126, 969–980.

- Van der Linden, I.; Cottyn, B.; Uyttendaele, M.; Vlaemynck, G.; Heyndrickx, M.; Maes, M.; Holden, N. Microarray-based screening of differentially expressed genes of E. coli O157: H7 Sakai during preharvest survival on butterhead lettuce. Agriculture 2016, 6, 6.

- Fonseca, J.; Fallon, S.; Sanchez, C.; Nolte, K. Escherichia coli survival in lettuce fields following its introduction through different irrigation systems. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 893–902.

- Kisluk, G.; Yaron, S. Presence and persistence of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium in the phyllosphere and rhizosphere of spray-irrigated parsley. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 4030–4036.

- Barak, J.D.; Kramer, L.C.; Hao, L.-Y. Colonization of tomato plants by Salmonella enterica is cultivar dependent, and type 1 trichomes are preferred colonization sites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 498–504.

- Golberg, D.; Kroupitski, Y.; Belausov, E.; Pinto, R.; Sela, S. Salmonella Typhimurium internalization is variable in leafy vegetables and fresh herbs. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 250–257.

- Quilliam, R.S.; Williams, A.P.; Jones, D.L. Lettuce cultivar mediates both phyllosphere and rhizosphere activity of Escherichia coli O157: H7. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33842.

- Macarisin, D.; Patel, J.; Bauchan, G.; Giron, J.A.; Ravishankar, S. Effect of spinach cultivar and bacterial adherence factors on survival of Escherichia coli O157: H7 on spinach leaves. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1829–1837.

- Hunter, P.J.; Shaw, R.K.; Berger, C.N.; Frankel, G.; Pink, D.; Hand, P. Older leaves of lettuce (Lactuca spp.) support higher levels of Salmonella enterica ser. Senftenberg attachment and show greater variation between plant accessions than do younger leaves. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, fnv077.

- Crozier, L.; Hedley, P.E.; Morris, J.; Wagstaff, C.; Andrews, S.C.; Toth, I.; Jackson, R.W.; Holden, N.J. Whole-transcriptome analysis of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli O157: H7 (Sakai) suggests plant-species-specific metabolic responses on exposure to spinach and lettuce extracts. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1088.

- Erickson, M.C.; Liao, J.-Y.; Payton, A.S.; Cook, P.W.; Den Bakker, H.C.; Bautista, J.; Pérez, J.C.D. Fate of enteric pathogens in different spinach cultivars cultivated in growth chamber and field systems. Food Qual. Saf. 2018, 2, 221–228.

- Roy, D.; Melotto, M. Stomatal response and human pathogen persistence in leafy greens under preharvest and postharvest environmental conditions. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 148, 76–82.

- Wong, C.W.; Wang, S.; Levesque, R.C.; Goodridge, L.; Delaquis, P. Fate of 43 Salmonella strains on lettuce and tomato seedlings. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 1045–1051.

- Deng, L.-Z.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Pan, Z.; Vidyarthi, S.K.; Xu, J.; Zielinska, M.; Xiao, H.-W. Emerging chemical and physical disinfection technologies of fruits and vegetables: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2481–2508.

- Gil, M.I.; Selma, M.V.; López-Gálvez, F.; Allende, A. Fresh-cut product sanitation and wash water disinfection: Problems and solutions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 134, 37–45.

- Cui, H.; Ma, C.; Li, C.; Lin, L. Enhancing the antibacterial activity of thyme oil against Salmonella on eggshell by plasma-assisted process. Food Control 2016, 70, 183–190.

- Tiwari, B.K.; O’Donnell, C.P.; Brunton, N.P.; Cullen, P.J. Degradation kinetics of tomato juice quality parameters by ozonation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 1199–1205.

- Rastogi, N.; Raghavarao, K.; Balasubramaniam, V.; Niranjan, K.; Knorr, D. Opportunities and challenges in high pressure processing of foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 47, 69–112.

- Kruk, Z.A.; Yun, H.; Rutley, D.L.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Jo, C. The effect of high pressure on microbial population, meat quality and sensory characteristics of chicken breast fillet. Food Control 2011, 22, 6–12.

- Jacob, C.; Melotto, M. Human pathogen colonization of lettuce dependent upon plant genotype and defense response activation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1769.

- Kljujev, I.; Raicevic, V.; Jovicic-Petrovic, J.; Vujovic, B.; Mirkovic, M.; Rothballer, M. Listeria monocytogenes—Danger for health safety vegetable production. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 120, 23–31.

- Carrascosa, C.; Raheem, D.; Ramos, F.; Saraiva, A.; Raposo, A. Microbial biofilms in the food industry—A comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2014.

- Barak, J.D.; Jahn, C.E.; Gibson, D.L.; Charkowski, A.O. The role of cellulose and O-antigen capsule in the colonization of plants by Salmonella enterica. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 1083–1091.

- Wagner, C.; Hensel, M. Adhesive mechanisms of Salmonella enterica. Bact. Adhes. Chem. Biol. Phys. 2011, 715, 17–34.

- Karamanoli, K.; Thalassinos, G.; Karpouzas, D.; Bosabalidis, A.; Vokou, D.; Constantinidou, H.-I. Are leaf glandular trichomes of oregano hospitable habitats for bacterial growth? J. Chem. Ecol. 2012, 38, 476–485.

- Patel, J.; Sharma, M. Differences in attachment of Salmonella enterica serovars to cabbage and lettuce leaves. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 139, 41–47.

- Ge, C.; Lee, C.; Lee, J. The impact of extreme weather events on Salmonella internalization in lettuce and green onion. Food Res. Int. 2012, 45, 1118–1122.

- López-Gálvez, F.; Gil, M.I.; Allende, A. Impact of relative humidity, inoculum carrier and size, and native microbiota on Salmonella ser. Typhimurium survival in baby lettuce. Food Microbiol. 2018, 70, 155–161.

- Pu, S.; Beaulieu, J.C.; Prinyawiwatkul, W.; Ge, B. Effects of plant maturity and growth media bacterial inoculum level on the surface contamination and internalization of Escherichia coli O157: H7 in growing spinach leaves. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 2313–2320.

- Hirneisen, K.A.; Sharma, M.; Kniel, K.E. Human enteric pathogen internalization by root uptake into food crops. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2012, 9, 396–405.

- Wright, K.M.; Crozier, L.; Marshall, J.; Merget, B.; Holmes, A.; Holden, N.J. Differences in internalization and growth of Escherichia coli O157: H7 within the apoplast of edible plants, spinach and lettuce, compared with the model species Nicotiana benthamiana. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 555–569.

- Erickson, M.C.; Webb, C.C.; Davey, L.E.; Payton, A.S.; Flitcroft, I.D.; Doyle, M.P. Biotic and abiotic variables affecting internalization and fate of Escherichia coli O157: H7 isolates in leafy green roots. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 872–879.

- Torres, A.G.; Jeter, C.; Langley, W.; Matthysse, A.G. Differential binding of Escherichia coli O157: H7 to alfalfa, human epithelial cells, and plastic is mediated by a variety of surface structures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 8008–8015.

- Ukuku, D.O.; Fett, W.F. Effects of cell surface charge and hydrophobicity on attachment of 16 Salmonella serovars to cantaloupe rind and decontamination with sanitizers. J. Food Prot. 2006, 69, 1835–1843.

- Saggers, E.; Waspe, C.; Parker, M.; Waldron, K.; Brocklehurst, T. Salmonella must be viable in order to attach to the surface of prepared vegetable tissues. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 105, 1239–1245.

- Tan, M.S.; Rahman, S.; Dykes, G.A. Pectin and xyloglucan influence the attachment of Salmonella enterica and Listeria monocytogenes to bacterial cellulose-derived plant cell wall models. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 680–688.

- Annous, B.A.; Solomon, E.B.; Cooke, P.H.; Burke, A. Biofilm formation by Salmonella spp. on cantaloupe melons. J. Food Saf. 2005, 25, 276–287.

- Beattie, G.A.; Lindow, S.E. Bacterial colonization of leaves: A spectrum of strategies. Phytopathology 1999, 89, 353–359.

- Warner, J.; Rothwell, S.; Keevil, C. Use of episcopic differential interference contrast microscopy to identify bacterial biofilms on salad leaves and track colonization by Salmonella Thompson. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 918–925.

- Takeuchi, K.; Matute, C.M.; Hassan, A.N.; Frank, J.F. Comparison of the attachment of Escherichia coli O157: H7, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Pseudomonas fluorescens to lettuce leaves. J. Food Prot. 2000, 63, 1433–1437.

- Lapidot, A.; Yaron, S. Transfer of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium from contaminated irrigation water to parsley is dependent on curli and cellulose, the biofilm matrix components. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 618–623.

- Matthysse, A.G.; Kijne, J.W. Attachment of Rhizobiaceae to plant cells. In The Rhizobiaceae: Molecular Biology of Model Plant-Associated Bacteria; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 235–249.

- Jeter, C.; Matthysse, A.G. Characterization of the binding of diarrheagenic strains of E. coli to plant surfaces and the role of curli in the interaction of the bacteria with alfalfa sprouts. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2005, 18, 1235–1242.

- Solomon, E.; Matthews, K. Interaction of live and dead Escherichia coli O157: H7 and fluorescent microspheres with lettuce tissue suggests bacterial processes do not mediate adherence. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 42, 88–93.

- Kondo, N.; Murata, M.; Isshiki, K. Efficiency of sodium hypochlorite, fumaric acid, and mild heat in killing native microflora and Escherichia coli O157: H7, Salmonella Typhimurium DT104, and Staphylococcus aureus attached to fresh-cut lettuce. J. Food Prot. 2006, 69, 323–329.

- Shirron, N.; Kisluk, G.; Zelikovich, Y.; Eivin, I.; Shimoni, E.; Yaron, S. A comparative study assaying commonly used sanitizers for antimicrobial activity against indicator bacteria and a Salmonella Typhimurium strain on fresh produce. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 2413–2417.

- Wells, J.; Butterfield, J. Salmonella contamination associated with bacterial soft rot of fresh fruits and vegetables in the marketplace. Plant Dis. 1997, 81, 867–872.

- Poza-Carrion, C.; Suslow, T.; Lindow, S. Resident bacteria on leaves enhance survival of immigrant cells of Salmonella enterica. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 341–351.

- Potnis, N.; Soto-Arias, J.P.; Cowles, K.N.; van Bruggen, A.H.; Jones, J.B.; Barak, J.D. Xanthomonas perforans colonization influences Salmonella enterica in the tomato phyllosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3173–3180.

- Kwan, G.; Charkowski, A.O.; Barak, J.D. Salmonella enterica suppresses Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum population and soft rot progression by acidifying the microaerophilic environment. MBio 2013, 4, e00557-12.

More

Information

Subjects:

Microbiology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

756

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

24 Mar 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No