Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Victor Fuentes-Barrera | -- | 2093 | 2023-03-20 02:50:17 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | + 3 word(s) | 2096 | 2023-03-20 02:52:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Valdebenito-Navarrete, H.; Fuentes-Barrera, V.; Smith, C.T.; Salas-Burgos, A.; Zuniga, F.A.; Gomez, L.A.; García-Cancino, A. SARS-CoV-2 and Probiotics. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42329 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Valdebenito-Navarrete H, Fuentes-Barrera V, Smith CT, Salas-Burgos A, Zuniga FA, Gomez LA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and Probiotics. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42329. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Valdebenito-Navarrete, Héctor, Victor Fuentes-Barrera, Carlos T. Smith, Alexis Salas-Burgos, Felipe A. Zuniga, Leonardo A. Gomez, Apolinaria García-Cancino. "SARS-CoV-2 and Probiotics" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42329 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Valdebenito-Navarrete, H., Fuentes-Barrera, V., Smith, C.T., Salas-Burgos, A., Zuniga, F.A., Gomez, L.A., & García-Cancino, A. (2023, March 20). SARS-CoV-2 and Probiotics. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42329

Valdebenito-Navarrete, Héctor, et al. "SARS-CoV-2 and Probiotics." Encyclopedia. Web. 20 March, 2023.

Copy Citation

SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Coronaviridae, subfamily Orthocoronaviridae, characterized by spike (S) proteins, which allow it to bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor present on epithelial cells. Probiotics are defined as “live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host”. More specifically, immunobiotics are probiotics capable of beneficially regulating the mucosal immune system. The use of probiotics could reduce the economic costs associated with the control of respiratory diseases.

probiotic

SARS-CoV-2

immunomodulation

1. Introduction

The viral infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 rapidly spread throughout the world, prompting the WHO to classify it as a pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the Orthocoronaviridae subfamily, a member of the Coronaviridae family. SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded RNA virus whose genome corresponds to approximately 27–32 kb. It uses the spike protein to infect lung and intestinal epithelial cells. These cells possess a membrane receptor protein, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), used as an entry point by some coronaviruses. The viral RNA is released into the cytoplasm of host cells, where the required viral proteins, either structural ones or those for the replication of its genetic material, are transcribed [1]. Since ACE2 is highly expressed by the lungs and the intestine, they are the most affected organs. SARS-CoV-2 infection causes dysbiosis and an uncontrolled immune response, which may even cause the death of an individual [2].

Currently, infection by SARS-CoV-2 is treated using hydroxychloroquine, tocilizumab, antivirals, antibiotics, and treatments to handle the symptomatology associated with the infection, either alone or in combinations, sometimes without success [3]. This fact has encouraged a number of companies and researchers to collaboratively develop vaccines that are administered in different doses and that have shown different percentages of effectiveness against new variants of the virus. Among the variants, Alpha (known as 501Y.V1 according to the GISAID nomenclature or variant B.1.1.7 according to the Pango nomenclature), Beta (501Y.V2 or B.1.351), Gamma (501Y. V3 or P1), and Delta (G/478K.V1 or B.1.617.2) can be mentioned [3].

Taking into consideration the ineffectiveness of anti-COVID-19 drugs and differences in the doses as well as the effectiveness of the vaccines, resulting from the advent of new variants, new therapeutic alternatives have been sought. One of these proposed therapeutic alternatives is the administration of probiotics [4]; even more specifically, immunobiotics. Immunobiotics are probiotic strains capable of beneficially regulating the mucosal immune system [5]. Considering the fact that the intestinal microbiota may beneficially modulate intestinal immunity, as well as pulmonary immunity by means of the intestine–lung axis [6], there emerges the possibility of taking advantage of the immunomodulating properties of immunobiotic bacteria. Immunobiotic bacteria, when colonizing the gastrointestinal tract of an individual, could induce a beneficial effect on the immune system of a host at both the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems. This result is due to the fact that the local immunological regulation by the specific microbiota of the gut has a long-range immunological impact that reaches the lung [7]. Therefore, probiotics may provide a wide scope of benefits to consumers, including the prevention and treatment of infections of the upper respiratory tract [8].

2. SARS-CoV-2: A High-Prevalence Threat to Global Public Health

The emergence of new viruses capable of causing human respiratory diseases has turned these pathologies into global challenges. Respiratory viral infections are among the most prevalent ones, contributing significantly to the morbidity and mortality rates in all age groups. Furthermore, they can rapidly evolve and cross species barriers into other host populations. Moreover, they are associated with severe clinical diseases and mortality [9]. Since there are no means with which to control emerging infectious diseases, they are problematic in terms of being treated and efficiently prevented. Among these emergent respiratory pathologies, it is possible to include severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which emerged in 2002, infected 8098 persons in 26 countries, and caused 774 deaths, its causative agent being the SARS-CoV-1 virus. Later on, in 2012, coronavirus reappeared in the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East (MERS-CoV virus), and most recently, in 2019, in China (SARS-CoV-2 virus). SARS-CoV-2 is the causative agent of COVID-19 [10], becoming a worldwide public health emergency [11].

By October 2022, SARS-CoV-2 had caused nearly 61,577 deaths as a consequence of approximately 4,722,184 cases in Chile, while Cuba suffered a total of 8530 deaths as the result of 1,111,290 cases, Argentina recorded 129,991 deaths caused by 9,718,875 cases, and Uruguay reported a total of 7518 deaths due to 990,560 cases. These countries are reaching the higher percentages of complete immunization schemes in Latin America, led by Chile, with 91.46% of its total population being vaccinated. At the worldwide level, it is estimated that the numbers of cases and deaths reach figures of approximately 629,000,000 and 6,590,000, respectively [12][13].

By the end of February 2021, 1755 cases requiring treatment at an intensive care unit were reported in Chile, 1513 of which required invasive mechanical ventilation, the highest figures recorded in the country during the whole pandemic [13].

Considering its known epidemiological background, SARS-CoV-2 is an excellent model with which to develop strategies to control emerging severe viral infections, centering efforts to prevent disease.

3. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Generates an Uncontrolled Immune Response

SARS-CoV-2 is a pneumotropic virus transmitted from person to person through respiratory secretions, including droplets produced while coughing, sneezing, or even speaking. Contact with contaminated surfaces or fomites also contributes to its transmission [14][15]. In closed environments with inadequate ventilation SARS-CoV-2 is a highly infectious pathogen, being in potentially infectious aerosols for hours and possessing the ability to travel for tens of meters before landing on surfaces where the virus can survive for days [16][17].

SARS-CoV-2 infection occurs due to the binding of its spike protein with the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor present on epithelial cells. This infection can be divided into three phases: (1) asymptomatic—the virus being detectable or not; (2) symptomatic—non-severe, presence of detectable virus, including infection, fever, dry cough, myalgia, fatigue, and breathing difficulties, occasionally diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting [18], patients showing gastrointestinal symptoms being the ones with the worse prognosis [19]; and (3) symptomatic—severe respiratory symptoms due to a high viral load [20] cause a storm of cytokines in the immune system. The infection is characterized by high serum levels of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-17, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, TNFα, IP10, MCP1, MIP1A, and MIP1B, but, in particular, it influences a sustained increase in IL-6 and IL-1β [21][22][23], which may result in the death of a patient. This immune response generates uncertainty with regard to the evolution of a patient’s diagnosis; for this reason, the Dublin–Boston scoring parameter was developed. It allows us to predict the probability that a patient will require hospitalization, intensive care, or mechanical ventilation, for which the blood IL-6 and IL-10 quotients during infection are calculated [24].

On the other hand, the humoral immune response is mediated by antibodies, which are detectable approximately between four and six days after RT-PCR, confirming an infection. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies show neutralizing capacity, can contribute to eliminating the virus, and, subsequently, to preventing the disease. Nevertheless, it is yet uncertain if they provide long-lasting immunity and protection against reinfection [25], because, in mild COVID-19 patients, the IgG antibodies’ response against the virus decreases rapidly (2 to 4 months), suggesting that, in these patients, this may be a short time response [26]. This short time response may be the consequence of the loss of Bcl-6-expressing T follicular helper cells and germinal centers in patients suffering mild COVID-19 infection [27].

4. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Causes Intestinal Dysbiosis Associated with a Loss in Intestinal Mucosa

The main symptoms associated with the SARS-CoV-2 infection include fever, dry cough, myalgia, fatigue, respiratory distress, and, less frequently, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting [19]. Besides elderly patients, patients with underlying pathologies, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, or cardiovascular diseases, may develop clinical presentations that are much more severe. These include acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock, which might lead to a patient’s death [20]. In the intestine an infection causes nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting; moreover, recent studies suggest that SARS-CoV-2 alters the intestinal microbiota [21]. This alteration is possibly due to the reduced availability of ACE2 during an infection by this virus, which could be sufficient to alter the composition of the intestinal microbiota [22]. Some evidence also supports the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 may induce alterations in the blood barrier of the intestine, promoting the abnormal absorption of microbial molecules or the dissemination of bacteria. This stimulates the systemic inflammatory response, which, in turn, contributes to multiorgan dysfunction, septic shock, or gastrointestinal and fecal dysbiosis [28].

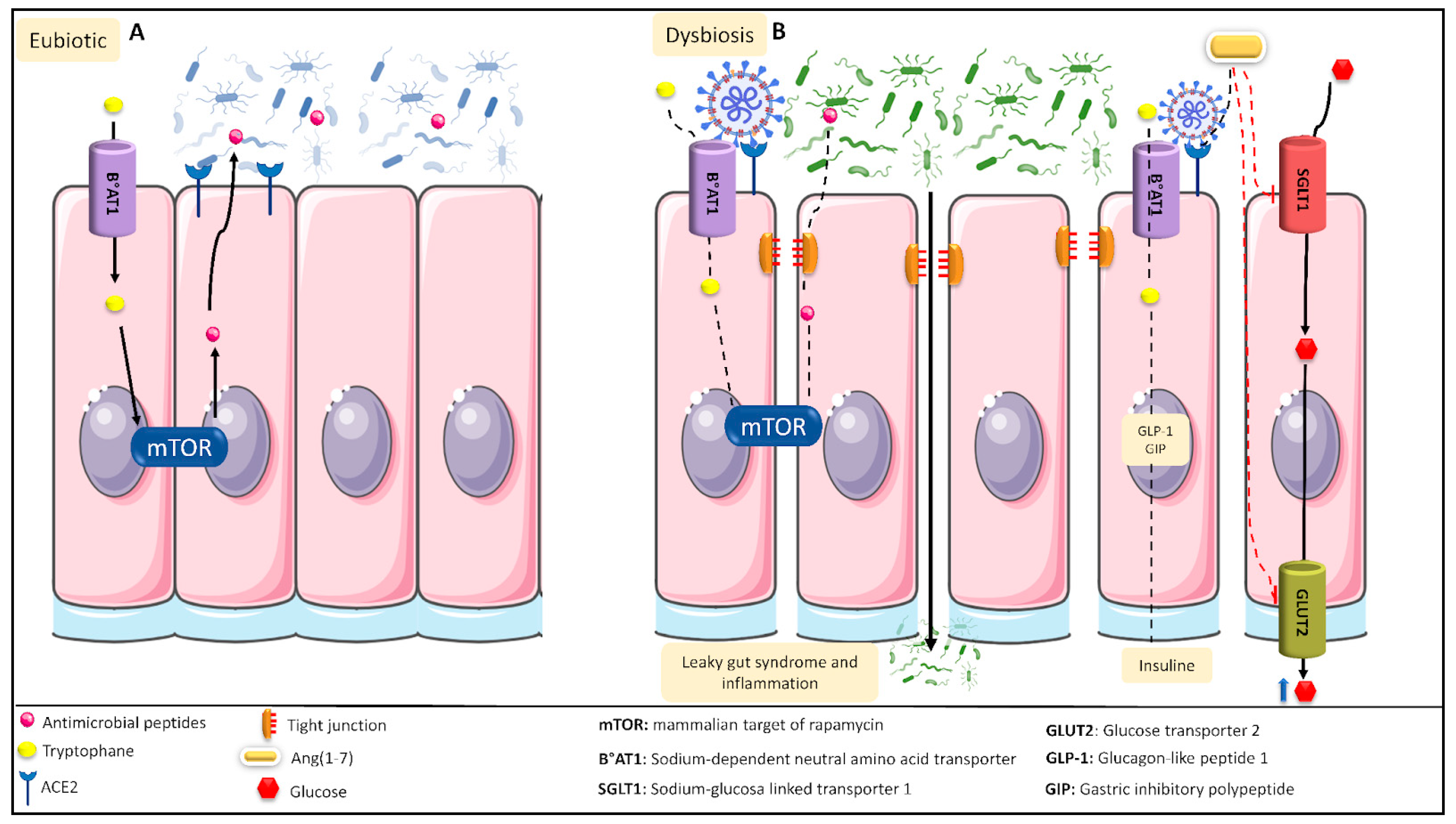

A consequence of dysbiosis is the colonization of the intestine by opportunistic microorganisms, such as members of the genera Parabacteroides, Faecalibacterium, and Clostridium, to the detriment of beneficial commensal genera, such as those belonging to the phylum Firmicutes. Under normal circumstances, ACE2 participates in the renin–angiotensin system (RAS), hydrolyzing Ang II into Ang (1-7) [29], which is involved in the inhibition of glucose transport to the intestine and in the production as well as release of insulin in the presence of high glucose levels [30]. During SARS-CoV-2 dysbiosis, due to the blocking of ACE2 by the virus, there occurs a decrease in the concentration of Ang (1-7), which reduces the availability of insulin and increases intestinal glucose, contributing to leaky gut syndrome and causing an increase in intestinal glucose. Figure 1 shows a diagram of the intestinal dysbiosis process.

Figure 1. Intestinal eubiotic and SARS-CoV-2-induced intestinal dysbiosis. (A) In a general intestinal environment in eubiotic conditions, tryptophan can enter into the intestinal tract’s epithelial cells, generating the production of antimicrobial peptides that will regulate the intestinal microbiota. In addition, ACE2 can convert Ang II into Ang (1-7), which, after binding to its receptor, Mas, blocks intestinal glucose transport. (B) The various proinflammatory mechanisms caused during SARS-CoV-2 infection generate an intestinal dysbiosis condition. Under this condition, SARS-CoV-2 can block the B°AT1 receptor, preventing both the passage of tryptophan into the epithelial cells and the production of antimicrobial peptides. SARS-CoV-2 can also disrupt the tight junctions of the cells, producing leaky gut syndrome and inflammation. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 receptor, preventing the formation of Ang (1-7) and favoring the activity of the SGLT1 as well as GLUT2 transporters, increasing the intestinal glucose levels.

5. Current Strategies to Deal with COVID-19

5.1. Vaccines, the Only Preventive Therapy to Deal with COVID-19

Up to 15 February 2021, more than 200 vaccines were in the process of being developed and 50 of them were being subjected to clinical phases; only 11 had progressed to phase 3 and become authorized to be used in the population [31]. Reports from 3 March 2021 indicate that only twelve have been approved by at least one country to immunize their population. In Chile, vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 started on 24 December 2020, and, so far, in this country only five vaccines have received emergency approval: BNT162b2 (developed by Pfizer, Pearl River, NY, USA, EE.UU. and BioNTech, Mainz, Germany), CoronaVac (produced by Sinovac Biotech, Pekin, China), ChAdOx1-S (produced by AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK and Oxford, Oxford, UK) [32], CanSino (produced by CanSino Biologics Inc., Tianjin, China), and mRNA-1273 (produced by Moderna, Cambridge, MA, USA, EE.UU.). Vaccines are the only prevention strategy being developed against COVID-19. It is noteworthy that these vaccines possess certain negative aspects; for example, a few individuals will not be able to receive the vaccine, such as those with severe allergies to any of the vaccine components [33][34][35]. The probability of the occurrence of mutations of the virus does exist, and vaccines may lose effectiveness against these new variants [36]. Finally, it is still unknown as to how long-lasting immunity is against the virus after vaccination, nor when the required fraction of the population will be vaccinated with adequate doses to have the virus and its variants under control [37].

5.2. Current Treatments to Control SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The redeployment of drugs has been proposed; that is to say, to analyze the possibility of using drugs already in the market as antivirals or for other purposes, to validate their efficacy against SARS-CoV-2, and, if appropriate, to accelerate their application against COVID-19 [38]. Among these drugs, the researchers can find remdesivir (GS-5734; Gilead Sciences Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) and favipiravir (Avigan, Toyama Chemical. Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), which, as part of their primary functions, inhibit the replication of the virus and control the storm of cytokines caused by the infection [39][40].

5.3. Co-Adjuvant Treatments against COVID-19

The use of co-adjuvants, such as high doses of vitamin D [41], intravenous vitamin C [42], zinc supplements [43], or medicinal plants and their active components, has been proposed as a supplementary treatment [44]. They are under investigation, but none have been accepted as being a definitive treatment. Reasons to preclude their use so far include only a short period of study, insufficient evidence to correctly justify their action mechanisms against the virus, and a lack of knowledge regarding possible adverse effects that they could cause in the population, mainly in the risk groups.

References

- Forchette, L.; Sebastian, W.; Liu, T. A Comprehensive Review of COVID-19 Virology, Vaccines, Variants, and Therapeutics. Curr. Med. Sci. 2021, 41, 1037–1051.

- Dhar, D.; Mohanty, A. Gut microbiota and Covid-19-possible link and implications. Virus Res. 2020, 285, 198018.

- Fiolet, T.; Kherabi, Y.; MacDonald, C.J.; Ghosn, J.; Peiffer-Smadja, N. Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: A narrative review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 202–221.

- Todorov, S.D.; Tagg, J.R.; Ivanova, I.V. Could Probiotics and Postbiotics Function as “Silver Bullet” in the Post-COVID-19 Era? Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 1499–1507.

- Sundararaman, A.; Ray, M.; Ravindra, P.V.; Halami, P.M. Role of probiotics to combat viral infections with emphasis on COVID-19. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8089–8104.

- Fanos, V.; Pintus, M.C.; Pintus, R.; Marcialis, M.A. Lung microbiota in the acute respiratory disease: From coronavirus to metabolomics. J. Pediatr. Neonatal Individ. Med. (JPNIM) 2020, 9, e090139.

- Bingula, R.; Filaire, M.; Radosevic-Robin, N.; Bey, M.; Berthon, J.Y.; Bernalier-Donadille, A.; Vasson, M.P.; Filaire, E. Desired Turbulence? Gut-Lung Axis, Immunity, and Lung Cancer. J. Oncol. 2017, 2017, 5035371.

- Altadill, T.; Espadaler-Mazo, J.; Liong, M.T. Effects of a Lactobacilli Probiotic on Reducing Duration of URTI and Fever, and Use of URTI-Associated Medicine: A Re-Analysis of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 528.

- Gutiérrez, V.; Cerda, J.; Le Corre, N.; Medina, R.; Ferrés, M. Caracterización clínica y epidemiológica de infección asociada a atención en salud por virus influenza en pacientes críticos. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2019, 36, 274–282.

- Pastrián-Soto, G. Bases Genéticas y Moleculares del COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2). Mecanismos de Patogénesis y de Respuesta Inmune. Int. J. Odontostomat. 2020, 14, 331–337.

- Mahooti, M.; Miri, S.M.; Abdolalipour, E.; Ghaemi, A. The immunomodulatory effects of probiotics on respiratory viral infections: A hint for COVID-19 treatment? Microb. Pathog. 2020, 148, 104452.

- Dong, E.; Du, H.; Gardner, L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Inf. Dis. 2020, 20, 533–534.

- Cifras: Situación Nacional de COVID-19 en Chile. Available online: https://www.gob.cl/coronavirus/cifrasoficiales (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Leclerc, Q.J.; Fuller, N.M.; Knight, L.E.; CMMID COVID-19 Working Group; Funk, S.; Knight, G.M. What settings have been linked to SARS-CoV-2 transmission clusters? Wellcome Open Res. 2020, 5, 83.

- Liu, M.; Caputi, T.L.; Dredze, M.; Kesselheim, A.S.; Ayers, J.W. Internet searches for unproven COVID-19 therapies in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1116–1118.

- van Doremalen, N.; Bushmaker, T.; Morris, D.H.; Holbrook, M.G.; Gamble, A.; Williamson, B.N.; Tamin, A.; Harcourt, J.L.; Thornburg, N.J.; Gerber, S.I.; et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1564–1567.

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Wang, Y.; Molina, M.J. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14857–14863.

- Ozma, M.A.; Maroufi, P.; Khodadadi, E.; Köse, Ş.; Esposito, I.; Ganbarov, K.; Dao, S.; Esposito, S.; Dal, T.; Zeinalzadeh, E.; et al. Clinical manifestation, diagnosis, prevention and control of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) during the outbreak period. Infez. Med. 2020, 28, 153–165.

- Maguiña Vargas, C.; Gastelo Acosta, R.; Tequen Bernilla, A. El nuevo Coronavirus y la pandemia del Covid-19. Rev. Med. Herediana 2020, 31, 125–131.

- Pan, L.; Mu, M.; Yang, P.; Sun, Y.; Wang, R.; Yan, J.; Li, P.; Hu, B.; Wang, J.; Hu, C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 Patients With Digestive Symptoms in Hubei, China: A Descriptive, Cross-Sectional, Multicenter Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 766–773.

- Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shao, C.; Huang, J.; Gan, J.; Huang, X.; Bucci, E.; Piacentini, M.; Ippolito, G.; Melino, G. COVID-19 infection: The perspectives on immune responses. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 1451–1454.

- Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M.; Sanchez, E.; Tattersall, R.S.; Manson, J.J.; HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020, 395, 1033–1034.

- Sanz, J.M.; Gómez Lahoz, A.M.; . Martín, R.O. Papel del sistema inmune en la infección por el SARS-CoV-2: Inmunopatología de la COVID-19 . Medicine 2021, 13, 1917–1931.

- McElvaney, O.J.; Hobbs, B.D.; Qiao, D.; McElvaney, O.F.; Moll, M.; McEvoy, N.L.; Clarke, J.; O’Connor, E.; Walsh, S.; Cho, M.H.; et al. A linear prognostic score based on the ratio of interleukin-6 to interleukin-10 predicts outcomes in COVID-19. eBioMedicine 2020, 61, 103026.

- Kindler, E.; Thiel, V. SARS-CoV and IFN: Too little, too late. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 139–141.

- Villena, J.; Kitazawa, H. The Modulation of Mucosal Antiviral Immunity by Immunobiotics: Could They Offer Any Benefit in the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic? Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 699.

- Kaneko, N.; Kuo, H.H.; Boucau, J.; Farmer, J.R.; Allard-Chamard, H.; Mahajan, V.S.; Piechocka-Trocha, A.; Lefteri, K.; Osborn, M.; Bals, J.; et al. Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness Specimen Working Group. Loss of Bcl-6-Expressing T Follicular Helper Cells and Germinal Centers in COVID-19. Cell 2020, 183, 143–157.e13.

- Ibarrondo, F.J.; Fulcher, J.A.; Goodman-Meza, D.; Elliott, J.; Hofmann, C.; Hausner, M.A.; Ferbas, K.G.; Tobin, N.H.; Aldrovandi, G.M.; Yang, O.O. Rapid decay of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in persons with mild Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1085–1087.

- Härdtner, C.; Mörke, C.; Walther, R.; Wolke, C.; Lendeckel, U. High glucose activates the alternative ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas and APN/Ang IV/IRAP RAS axes in pancreatic β-cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 795–804.

- Ni, W.; Yang, X.; Yang, D.; Bao, J.; Li, R.; Xiao, Y.; Hou, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, D.; et al. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID-19. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 422.

- Instituto de Salud Pública (ISP). Fases de Desarrollo de las Vacunas. Available online: https://www.ispch.cl/anamed/farmacovigilancia/vacunas/fases-de-desarrollo-de-las-vacunas/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Monasterio, F. Cómo Avanzan las Vacunas Contra el Covid-19 en Chile y el Mundo. Pauta. Available online: https://www.pauta.cl/ciencia-y-tecnologia/vacunacion-covid-chile-mundo-desarrollo-fechas (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pfizer—BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/index.html (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-legal-regulatory-and-policy-framework/pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-frequently-asked-questions (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Pfizer-BioNTech. Hoja Informativa para Proveedores de la Salud Que Administren la Vacuna (Proveedores de Vacunación). Available online: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Informaci%C3%B3n-para-prescribir-FDA-para-profesionales_vacuna-Pfizer-BioNTECH-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Singh, P.K.; Kulsum, U.; Rufai, S.B.; Mudliar, S.R.; Singh, S. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Leading to Antigenic Variations in Spike Protein: A Challenge in Vaccine Development. J. Lab. Physicians 2020, 12, 154–160.

- The Lancet Microbe. COVID-19 vaccines: The pandemic will not end overnight. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, E1.

- Serafin, M.B.; Bottega, A.; Foletto, V.S.; da Rosa, T.F.; Hörner, A.; Hörner, R. Drug repositioning is an alternative for the treatment of coronavirus COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105969.

- Jean, S.S.; Lee, P.I.; Hsueh, P.R. Treatment options for COVID-19: The reality and challenges. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 436–443.

- Chugh, H.; Awasthi, A.; Agarwal, Y.; Gaur, R.K.; Dhawan, G.; Chandra, R. A comprehensive review on potential therapeutics interventions for COVID-19. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 890, 173741.

- Mansur, J.L.; Tajer, C.; Mariani, J.; Inserra, F.; Ferder, L.; Manucha, W. Vitamin D high doses supplementation could represent a promising alternative to prevent or treat COVID-19 infection. Clin. Investig. Arterioscler. 2020, 32, 267–277.

- Boretti, A.; Banik, B.K. Intravenous vitamin C for reduction of cytokines storm in acute respiratory distress syndrome. PharmaNutrition 2020, 12, 100190.

- Oyagbemi, A.A.; Ajibade, T.O.; Aboua, Y.G.; Gbadamosi, I.T.; Adedapo, A.D.A.; Aro, A.O.; Adejumobi, O.A.; Thamahane-Katengua, E.; Omobowale, T.O.; Falayi, O.O.; et al. Potential health benefits of zinc supplementation for the management of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13604.

- Manzano-Santana, P.; Peñarreta, J.; Chóez-Guaranda, I.; Barragán, A.; Orellana-Manzano, A.; Rastrelli, L. Potential bioactive compounds of medicinal plants against new Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A review. Bionatura 2021, 6, 1653–1658.

More

Information

Subjects:

Respiratory System

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

771

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

20 Mar 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No