Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Danial Khayatan | -- | 2302 | 2023-03-17 22:03:52 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2302 | 2023-03-20 03:20:38 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Khayatan, D.; Razavi, S.M.; Arab, Z.N.; Khanahmadi, M.; Momtaz, S.; Butler, A.E.; Montecucco, F.; Markina, Y.V.; Abdolghaffari, A.H.; Sahebkar, A. Sirtuins in Cardiovascular Diseases. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42314 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Khayatan D, Razavi SM, Arab ZN, Khanahmadi M, Momtaz S, Butler AE, et al. Sirtuins in Cardiovascular Diseases. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42314. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Khayatan, Danial, Seyed Mehrad Razavi, Zahra Najafi Arab, Maryam Khanahmadi, Saeideh Momtaz, Alexandra E. Butler, Fabrizio Montecucco, Yuliya V. Markina, Amir Hossein Abdolghaffari, Amirhossein Sahebkar. "Sirtuins in Cardiovascular Diseases" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42314 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Khayatan, D., Razavi, S.M., Arab, Z.N., Khanahmadi, M., Momtaz, S., Butler, A.E., Montecucco, F., Markina, Y.V., Abdolghaffari, A.H., & Sahebkar, A. (2023, March 17). Sirtuins in Cardiovascular Diseases. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/42314

Khayatan, Danial, et al. "Sirtuins in Cardiovascular Diseases." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 March, 2023.

Copy Citation

Adverse cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes, such as sudden cardiac death, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke, are often catastrophic. Statins are frequently used to attenuate the risk of CVD-associated morbidity and mortality through their impact on lipids and they may also have anti-inflammatory and other plaque-stabilization effects via different signaling pathways. Different statins, including atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, pravastatin, pitavastatin, and simvastatin, are administered to manage circulatory lipid levels. In addition, statins are potent inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMGCoA) reductase via modulating sirtuins (SIRTs).

sirtuins

statins

cardiovascular diseases

HMGCoA reductase inhibitors

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the most common cause of death globally. Several factors, such as coronary atherosclerosis, lead to progression of CVDs. Complex interactions between inflammatory and metabolic processes lead to initiation and progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Genetic and mechanistic analyses have shown that lipoproteins, including apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and, in particular, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), play a crucial role in atherogenesis. Improvement in CVD treatment, and especially acute myocardial infarction, has significantly increased average life expectancy. Given that about 20% of the world’s population will be aged 65 or older by 2030, an exponential increase in CVD prevalence is predicted, as many more people will have coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and hypertension. In parallel, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and diabetes is predicted to increase markedly in elderly individuals, further promoting CVD morbidity and mortality [1]. It is believed that beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and diuretics, which are currently used for the prevention of CVDs, prevent the onset and/or progression of CVDs as well as attenuate symptoms. Statins act to prevent CVDs and modulate circulating lipid concentration through a reduction in the biosynthesis of cholesterol, thereby leading to hepatic upregulation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors and enhanced LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) removal from the bloodstream. Clinical trials have shown the efficacy of statins for both primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. The effect of statins may be dependent or independent of LDL-C. In addition, clinical studies have demonstrated the advantages of statins in diseases that are not explicitly aligned with LDL-C, though some of these findings can be directly related to a reduction in cholesterol [2]. Statins are mainly administered as HMGCoA reductase inhibitors due to their strong efficacy in reduction of LDL through suppression of cholesterol synthesis. Statins are further utilized to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease due to their pleiotropic properties, such as elevating eNOS activity, restoring or improving endothelial function, suppressing platelet aggregation, decreasing oxidative stress damage and inflammation, and increasing the stability of atherosclerotic plaque through various signaling pathways [3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]. A drug’s pleiotropic effects may or may not be associated with its primary mechanism of action. These and other emerging features might work in concert with statins’ LDL-C-lowering actions [2][13][14]. A more recently recognized pharmacological action of statins relates to its correlation with normalization of endothelial function, thus acting in the prevention of atherosclerosis at an early phase. Moreover, statins prevent dysfunction of smooth muscle cells and suppress the migration and activation of macrophages [15]. This suppression impacts the endothelium by preventing macrophage influx and may represent the mechanism by which signaling cascades lead to atherosclerosis and block the normal activity of endothelial cells, which statins restored. Given the pleiotropic effects of statins and their anti-inflammatory properties [16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24], statins are widely used in the treatment of atherosclerotic CVD. Further understanding of the mechanisms involved in the development of atherosclerosis may further guide the design of anti-dyslipidemia therapies. Much, however, is already known about the complex interactions that contribute to inflammation, which involve mRNA activity; the NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome; Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF-2); peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ); Wnt inhibitor Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1); extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 5/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (ERK5/Nrf2); and sirtuin (SIRTs) pathways [25]. SIRTs, silent mating information-regulating analogs, are involved in many pivotal regulatory signaling pathways in cells that are associated with metabolism, stress response, aging, and the development of cancer and chronic disease. All members of the SIRT family exert actions that can be reduced or induced upon deacetylation [26]. SIRTs preserve the stability of DNA and cells against oxidative stress by targeting cellular proteins, such as PPAR-γ and its coactivator (PGC-1α), AMPK, forkhead transcriptional factors, NF-κB, p53, eNOS, and protein tyrosine phosphatase [27].

2. Cholesterol, Inflammation and Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs)

There are several factors associated with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), including arterial hypertension, obesity, age, serum uric acid levels [28], and cholesterol. Although cholesterol is known to be associated with the development of CVDs, other factors (i.e., hypertension, obesity) have been implicated in promoting CVD [29]. For instance, it has been reported that uric acid is associated with kidney disease and cardiovascular conditions, such as hypertension and coronary artery disease [30]. Observational studies have shown that blood pressure levels are strongly correlated with the relative risk of stroke and heart disease. In line with the results of these studies, a systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg is considered to be optimal for preventing the adverse consequences of elevated blood pressure [31][32]. In addition, obesity has been recently demonstrated to be associated with cardiac structural changes independently of atherosclerotic diseases [29]. Nearly a century ago, a positive correlation between CVD and serum cholesterol was reported. Subsequently, several epidemiological and clinical investigations have established the association between increased circulating cholesterol and CVDs, especially atherosclerosis. In fact, the correlation between the level of cholesterol and death from coronary heart disease (CHD) is linear, with each 0.5 mmol/L (20 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol leading to a 12% rise in mortality from CHD. Reduction in cholesterol levels leads to reduction in CVD mortality [33]. Statins reduce cholesterol biosynthesis in the mevalonate (MVA) pathway and modulate inflammation, as a pleiotropic effect, which helps to reduce the incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), including cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality [34]. HMG-CoA is a biosynthetic intermediate for cholesterol and other isoprenoids, such as farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. Isoprenoids are important in cell proliferation and migration, as well as atherogenesis and vasculopathy-related inflammatory processes. A growing body of evidence suggests that statins have pleiotropic effects by inhibiting the generation of isoprenoid intermediates during cholesterol biosynthesis [2]. In general, lowering blood cholesterol levels, mainly LDL-C, attenuates vascular deposition and retention of cholesterol and apoB-containing lipoproteins, which are atherogenic [34]. Patients suffering from hyperlipidemia are almost twice as likely to develop CVD as those with normal concentrations of total cholesterol. Hence, early detection and management of hyperlipidemia is imperative for decreasing CVDs and preventing premature death [33]. Abnormal blood flow and plaque aggregations in the ventricle of the heart can provoke myocardial infarction, leading to congestive heart failure. Atherosclerosis is the most common coronary artery disorder, in which proliferation of fibrous tissue in the arterial wall occurs. Moreover, multiple factors, such as inflammation, with the related action of leukocytes, endothelium, and smooth muscle cells, along with low density lipoprotein (LDL) uptake, are critical factors in atherosclerosis progression and myocardial infarction. LDL does not infiltrate the endothelium of blood vessels in normal healthy conditions. However, LDL can pass through the endothelium to the sub-endothelium with subsequent formation of plaques, and abnormal endothelial cells are associated with LDL infiltration in this process. Furthermore, several signaling pathways have been associated with inflammation, including the NF-κB-, NLRP3-, PPAR-, and sirtuin-related pathways, all of which can be restored by appropriate therapies, such as statins [35].

3. Sirtuins and Related Signaling Pathways

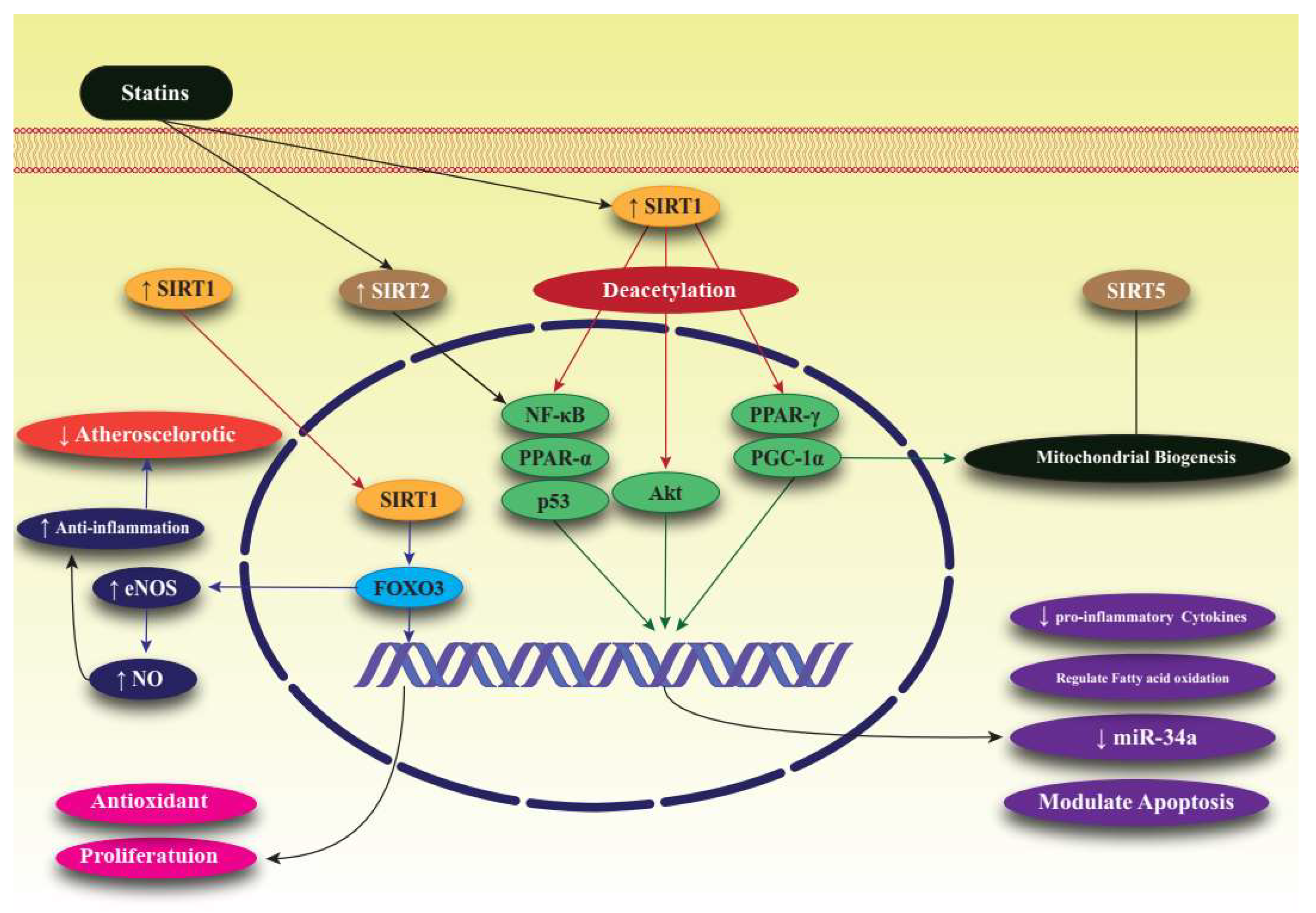

SIRTs are members of a large family of protein-modifying enzymes and NAD+-dependent deacetylators found in almost all organisms. The discovery of SIRTs as transcriptional silencing regulators of mating sites in yeasts attracted a great deal of attention [36]. The chemical structure of SIRTs is such that their enzymatic activities are regulated by various metabolites. Enzymatic reactions of SIRTs require NAD+ as a substrate, the concentration of which is determined by the nutritional status of the cell. SIRTs are completely dependent on NAD+, and the frequency of NAD+ and its breakdown in cells is closely related to the enzymatic activity of SIRTs. SIRTs convert NAD+ to nicotinamide which, in higher concentrations, can bind non-competitively and inhibit the activity of SIRTs [37][38]. SIRTs act in different parts of the cell as, for example, the acetylation of transcriptional regulators occurs in the nucleus and for other proteins occurs in the cytoplasm and mitochondria. These specific enzymes have important regulatory roles, such as regulating longevity in cells and organisms, fat motility in human cells, insulin secretion, cellular response to stress, enzyme activity, and basal transcription factor activity [39][40]. In mammals, the SIRT family consists of seven proteins that differ from each other in terms of enzymatic activity, tissue properties, and functions. Sirtuin has been studied in the context of prevention of diseases associated with aging and the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. SIRT1, present in the nucleus and cytosol, appears to be the only intervention that promotes increasing life expectancy [41]. SIRT2 is a NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase that acts as an energy sensor and transcription effector by controlling histone acetylation. These enzymes not only acetylate histones, but also destroy a wide range of transcriptional regulators, thereby controlling their activities. SIRT2 is mainly considered to be a cytosolic enzyme, but is also present in the nucleus [42]. SIRT3, SIRT4 and SIRT5 have a mitochondrial targeting sequence, and SIRT6 and SIRT7 are nuclear enzymes. Further studies are underway to determine SIRT7′s exact site of activity [43]. SIRTs can play a key role in various pathologies because they stimulate the activity of mitochondria and mitochondrial proteins. SIRTs regulate fat and glucose metabolism in response to physiological changes and, therefore, act as vital network regulators that control energy homeostasis and determine life expectancy in cells and organisms. SIRT activation occurs not only in metabolic diseases, such as diabetes and obesity, but also in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other neurodegenerative diseases and heart disease [44][45]. Though SIRTs are recognized as crucial targets for many diseases due to their wide and important physiological effects, the types of SIRTs and the pathways through which they exert their effects differ in different diseases. In mice, SIRT1 prevented diabetes, particularly in aged mice. The mediator NAD+ improved age-related type 2 diabetes in high-fat-fed mice through activation of SIRT1 [36][37][46][47]. SIRT1 was shown to increase insulin sensitivity by suppressing PTP1B tyrosine phosphatase and by increasing SIRT1 secretion through suppressing uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2). In addition to its positive effects in diabetes, SIRT1 in the hypothalamus positively affects the liver, muscle, and fat cells by, for example, stimulating adipogenesis, increasing insulin secretion, and by regulation of glucose homeostasis [48]. In relation to heart disease, increasing SIRT1 together with calorie restriction caused deacetylation and activation of eNOS, which ultimately increased NO, thereby dilating and protecting blood vessels [49]. SIRT2 can also redistribute endothelial cells in response to angiotensin II and mechanical traction by acetylating microtubules, and effects vascular regeneration in the setting of hypertension. SIRT3 can prevent cardiac hypertrophy by modulating mitochondrial homeostasis, and overexpression of SIRT6 suppressed angiotensin II-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [50][51][52]. SIRT1 improves learning and memory in mice, and its expression in the hippocampus caused effects on ERK1/2 phosphorylation and changes in the expression of genes involved in synaptic function [53]. In Alzheimer’s disease, SIRT1 prevented axonal degeneration and neurodegeneration, and also reduced tau proteins by deacetylating tau and reducing the production of beta-amyloids [54]. In animal models of Huntington’s disease, high expression of SIRT1 improved the neuropathology and increased BDNF expression, as well as extending lifespan [55]. In Parkinson’s disease, expression of SIRT1 increased life expectancy and protected neurons against neurotoxicity [30]. Unlike SIRT1, which has protective effects in neurodegenerative diseases, SIRT2 is toxic to neurons and causes increased accumulation of beta-amyloids and other proteins, making cells more vulnerable to apoptosis [56][57]. SIRT1 has been shown to modulate cellular stress and survival via promoting tumorigenesis in various cancers, including breast, prostate, colon, and pancreas. However, SIRT1 could be a tumor suppressor. For instance, an in vivo study on SIRT1 mutant mice has shown genomic instability, impairment of DNA repair response, and elevated incidence of tumorigenesis. In addition, SIRT1 concentrations are lower in hepatic cell carcinoma and breast cancer. SIRT3 has also been suggested as a mitochondrial tumor suppressor, but overall, the main role of SIRT1 and SIRT3 in tumor suppression is controversial [58][59]. The protective role of SIRT2 against cancer has been observed in various studies [60][61]. SIRT2 can prevent the formation of colonies and suppress the growth of tumor cells in glioma cell lines [62]. SIRT6, a tumor suppressor, can also acetylate the H3K9 and H3K56 histones and plays a considerable role in DNA repair in two-strand breaks, but its overexpression in a variety of cancer cells leads to increased apoptosis [63]. Lipid metabolism involves the synthesis, uptake, storage, and utilization of lipids and requires careful control. SIRTs affect various aspects of fat homeostasis. When the body’s total energy storage is maximized, glucose, fatty acids, and excess amino acids are utilized in the liver to synthesize fatty acids, which are sent into the white adipose tissue and stored as TGs. Fatty acid synthesis occurs in the cytosol, and a key transcription factor, LXR, controls the expression of genes involved in lipid synthesis [64][65]. SIRT1 can degrade LXR and increase its transcriptional activity, ultimately enhancing fatty acid synthesis. SIRT1 can also inhibit the fluctuation (decrease or increase) of fat movement through lipolysis by suppressing PPAR-γ activity, which is the main regulator of fat cell differentiation [66][67]. SIRT2 may also inhibit lipid production and promote lipolysis by deacetylation. SIRT6 is also involved in controlling the synthesis of fatty acids [68][69]. Figure 1 summarizes the effect of statins on sirtuins, as well as their signaling pathways (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of statins on SIRTs, particularly SIRT1, and related signaling pathways associated with lipid regulation. Forkhead box, class O3: FoxO3; nitric oxide: NO; endothelial nitric oxide: eNOS; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α: PPAR-α; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ: PPAR-γ; nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells: NF-κB; sirtuin: SIRT; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha: PGC-1α; protein kinase B: Akt; microRNA-34: miR-34.

References

- Costantino, S.; Paneni, F.; Cosentino, F. Ageing, metabolism and cardiovascular disease. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 2061–2073.

- Oesterle, A.; Laufs, U.; Liao, J.K. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins on the Cardiovascular System. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 229–243.

- Kilic, U.; Gok, O.; Elibol-Can, B.; Uysal, O.; Bacaksiz, A. Efficacy of statins on sirtuin 1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression: The role of sirtuin 1 gene variants in human coronary atherosclerosis. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2015, 42, 321–330.

- Bahrami, A.; Bo, S.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors on ageing: Molecular mechanisms. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 58, 101024.

- Gorabi, A.M.; Kiaie, N.; Pirro, M.; Bianconi, V.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of statins on the biological features of mesenchymal stem cells and therapeutic implications. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 26, 1259–1272.

- Reiner, Ž.; Hatamipour, M.; Banach, M.; Pirro, M.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Radenkovic, D.; Montecucco, F.; Sahebkar, A. Statins and the COVID-19 main protease: In silico evidence on direct interaction. Arch. Med. Sci. 2020, 16, 490–496.

- Sahebkar, A.; Serban, C.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Undas, A.; Lip, G.Y.; Muntner, P.; Bittner, V.; Ray, K.K.; Watts, G.F.; Hovingh, G.K.; et al. Association between statin use and plasma D-dimer levels. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 114, 546–557.

- Sohrevardi, S.M.; Nasab, F.S.; Mirjalili, M.R.; Bagherniya, M.; Tafti, A.D.; Jarrahzadeh, M.H.; Azarpazhooh, M.R.; Saeidmanesh, M.; Banach, M.; Jamialahmadi, T.; et al. Effect of atorvastatin on delirium status of patients in the intensive care unit: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 1423–1428.

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Mohammadi, S.M.; Heidari Beni, F.; Banach, M.; Guest, P.C.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Improved COVID-19 ICU admission and mortality outcomes following treatment with statins: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 579–595.

- Sahebkar, A.; Kotani, K.; Serban, C.; Ursoniu, S.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Jones, S.R.; Ray, K.K.; Blaha, M.J.; Rysz, J.; Toth, P.P.; et al. Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group. Statin therapy reduces plasma endothelin-1 concentrations: A meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, 433–442.

- Chamani, S.; Liberale, L.; Mobasheri, L.; Montecucco, F.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. The role of statins in the differentiation and function of bone cells. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 51, e13534.

- Dehnavi, S.; Kiani, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Biregani, A.F.; Banach, M.; Atkin, S.L.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Targeting AMPK by Statins: A Potential Therapeutic Approach. Drugs 2021, 81, 923–933.

- Davignon, J. Beneficial cardiovascular pleiotropic effects of statins. Circulation 2004, 109, III39–III43.

- Oesterle, A.; Liao, J.K. The Pleiotropic Effects of Statins—From Coronary Artery Disease and Stroke to Atrial Fibrillation and Ventricular Tachyarrhythmia. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2019, 17, 222–232.

- Wang, S.; Xie, X.; Lei, T.; Zhang, K.; Lai, B.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, Y.; Mao, G.; Xiao, L.; Wang, N. Statins Attenuate Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome by Oxidized LDL or TNFα in Vascular Endothelial Cells through a PXR-Dependent Mechanism. Mol. Pharmacol. 2017, 92, 256–264.

- Chruściel, P.; Sahebkar, A.; Rembek-Wieliczko, M.; Serban, M.C.; Ursoniu, S.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Jones, S.R.; Mosteoru, S.; Blaha, M.J.; Martin, S.S.; et al. Impact of statin therapy on plasma adiponectin concentrations: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 randomized controlled trial arms. Atherosclerosis 2016, 253, 194–208.

- Ferretti, G.; Bacchetti, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effect of statin therapy on paraoxonase-1 status: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 25 clinical trials. Prog. Lipid Res. 2015, 60, 50–73.

- Shakour, N.; Ruscica, M.; Hadizadeh, F.; Cirtori, C.; Banach, M.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Statins and C-reactive protein: In silico evidence on direct interaction. Arch. Med. Sci. 2020, 16, 1432–1439.

- Alikiaii, B.; Heidari, Z.; Bagherniya, M.; Askari, G.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. The Effect of Statins on C-Reactive Protein in Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 7104934.

- Bahrami, A.; Parsamanesh, N.; Atkin, S.L.; Banach, M.; Sahebkar, A. Effect of statins on toll-like receptors: A new insight to pleiotropic effects. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 135, 230–238.

- Koushki, K.; Shahbaz, S.K.; Mashayekhi, K.; Sadeghi, M.; Zayeri, Z.D.; Taba, M.Y.; Banach, M.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. Anti-inflammatory Action of Statins in Cardiovascular Disease: The Role of Inflammasome and Toll-Like Receptor Pathways. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 60, 175–199.

- Parsamanesh, N.; Moossavi, M.; Bahrami, A.; Fereidouni, M.; Barreto, G.; Sahebkar, A. NLRP3 inflammasome as a treatment target in atherosclerosis: A focus on statin therapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 73, 146–155.

- Pirro, M.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Bianconi, V.; Watts, G.F.; Banach, M.; Sahebkar, A. Effect of Statin Therapy on Arterial Wall Inflammation Based on 18F-FDG PET/CT: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventional Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 118.

- Khalifeh, M.; Penson, P.E.; Banach, M.; Sahebkar, A. Statins as anti-pyroptotic agents. Arch. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 1414–1417.

- Niedzielski, M.; Broncel, M.; Gorzelak-Pabiś, P.; Woźniak, E. New possible pharmacological targets for statins and ezetimibe. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110388.

- Zelenka, J.; Koncošová, M.; Ruml, T. Targeting of stress response pathways in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 583–602.

- Boutant, M.; Cantó, C. SIRT1 metabolic actions: Integrating recent advances from mouse models. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 5–18.

- Antonini-Canterin, F.; Di Nora, C.; Pellegrinet, M.; Vriz, O.; La Carrubba, S.; Carerj, S.; Zito, C.; Matescu, A.; Ravasel, A.; Cosei, I.; et al. Effect of uric acid serum levels on carotid arterial stiffness and intima-media thickness: A high resolution Echo-Tracking Study. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2019, 89.

- Antonini-Canterin, F.; Di Nora, C.; Poli, S.; Sparacino, L.; Iulian Cosei, I.; Ravasel, A.; Popescu, A.C.; Popescu, B.A. Obesity, Cardiac Remodeling, and Metabolic Profile: Validation of a New Simple Index beyond Body Mass Index. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 2018, 28, 18–25.

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, X.; Sun, C. SIRT1 Protects Dopaminergic Neurons in Parkinson’s Disease Models via PGC-1α-Mediated Mitochondrial Biogenesis. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 1393–1404.

- Di Nora, C.; Cioffi, G.; Iorio, A.; Rivetti, L.; Poli, S.; Zambon, E.; Barbati, G.; Sinagra, G.; Di Lenarda, A. Systolic blood pressure target in systemic arterial hypertension: Is lower ever better? Results from a community-based Caucasian cohort. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 48, 57–63.

- Mancia, G.; Fagard, R.; Narkiewicz, K.; Redón, J.; Zanchetti, A.; Böhm, M.; Christiaens, T.; Cifkova, R.; De Backer, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J. Hypertens. 2013, 31, 1281–1357.

- Sun, H.; Gusdon, A.M.; Qu, S. Effects of melatonin on cardiovascular diseases: Progress in the past year. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2016, 27, 408–413.

- Zhou, R.; Stouffer, G.A.; Smith, S.C., Jr. Targeting the Cholesterol Paradigm in the Risk Reduction for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Does the Mechanism of Action of Pharmacotherapy Matter for Clinical Outcomes? J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 26, 533–549.

- Chae, C.W.; Kwon, Y.W. Cell signaling and biological pathway in cardiovascular diseases. Arch. Pharmacal. Res. 2019, 42, 195–205.

- Haigis, M.C.; Sinclair, D.A. Mammalian sirtuins: Biological insights and disease relevance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010, 5, 253–295.

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Cantó, C.; Wanders, R.J.; Auwerx, J. The secret life of NAD+: An old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr. Rev. 2010, 31, 194–223.

- Bitterman, K.J.; Anderson, R.M.; Cohen, H.Y.; Latorre-Esteves, M.; Sinclair, D.A. Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast sir2 and human SIRT1. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 45099–45107.

- Picard, F.; Kurtev, M.; Chung, N.; Topark-Ngarm, A.; Senawong, T.; Machado De Oliveira, R.; Leid, M.; McBurney, M.W.; Guarente, L. Sirt1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing PPAR-gamma. Nature 2004, 429, 771–776.

- Motta, M.C.; Divecha, N.; Lemieux, M.; Kamel, C.; Chen, D.; Gu, W.; Bultsma, Y.; McBurney, M.; Guarente, L. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell 2004, 116, 551–563.

- Feige, J.N.; Auwerx, J. Transcriptional targets of sirtuins in the coordination of mammalian physiology. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2008, 20, 303–309.

- Imai, S.; Armstrong, C.M.; Kaeberlein, M.; Guarente, L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature 2000, 403, 795–800.

- Haigis, M.C.; Guarente, L.P. Mammalian sirtuins–emerging roles in physiology, aging, and calorie restriction. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 2913–2921.

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Auwerx, J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 225–238.

- Westphal, C.H.; Dipp, M.A.; Guarente, L. A therapeutic role for sirtuins in diseases of aging? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007, 32, 555–560.

- Banks, A.S.; Kon, N.; Knight, C.; Matsumoto, M.; Gutiérrez-Juárez, R.; Rossetti, L.; Gu, W.; Accili, D. SirT1 gain of function increases energy efficiency and prevents diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 333–341.

- Yoshino, J.; Mills, K.F.; Yoon, M.J.; Imai, S. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, a key NAD(+) intermediate, treats the pathophysiology of diet- and age-induced diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 528–536.

- Moynihan, K.A.; Grimm, A.A.; Plueger, M.M.; Bernal-Mizrachi, E.; Ford, E.; Cras-Méneur, C.; Permutt, M.A.; Imai, S. Increased dosage of mammalian Sir2 in pancreatic beta cells enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mice. Cell Metab. 2005, 2, 105–117.

- Nisoli, E.; Tonello, C.; Cardile, A.; Cozzi, V.; Bracale, R.; Tedesco, L.; Falcone, S.; Valerio, A.; Cantoni, O.; Clementi, E.; et al. Calorie restriction promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of eNOS. Science 2005, 310, 314–317.

- Hashimoto-Komatsu, A.; Hirase, T.; Asaka, M.; Node, K. Angiotensin II induces microtubule reorganization mediated by a deacetylase SIRT2 in endothelial cells. Hypertens. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hypertens. 2011, 34, 949–956.

- Sack, M.N. The role of SIRT3 in mitochondrial homeostasis and cardiac adaptation to hypertrophy and aging. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012, 52, 520–525.

- Yu, S.S.; Cai, Y.; Ye, J.T.; Pi, R.B.; Chen, S.R.; Liu, P.Q.; Shen, X.Y.; Ji, Y. Sirtuin 6 protects cardiomyocytes from hypertrophy in vitro via inhibition of NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 168, 117–128.

- Michán, S.; Li, Y.; Chou, M.M.; Parrella, E.; Ge, H.; Long, J.M.; Allard, J.S.; Lewis, K.; Miller, M.; Xu, W.; et al. SIRT1 is essential for normal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 9695–9707.

- Min, S.W.; Cho, S.H.; Zhou, Y.; Schroeder, S.; Haroutunian, V.; Seeley, W.W.; Huang, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Masliah, E.; Mukherjee, C.; et al. Acetylation of tau inhibits its degradation and contributes to tauopathy. Neuron 2010, 67, 953–966.

- Jeong, H.; Cohen, D.E.; Cui, L.; Supinski, A.; Savas, J.N.; Mazzulli, J.R.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Bordone, L.; Guarente, L.; Krainc, D. Sirt1 mediates neuroprotection from mutant huntingtin by activation of the TORC1 and CREB transcriptional pathway. Nat. Med. 2011, 18, 159–165.

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.X.; Xie, W.; Le, W.; Fan, Z.; Jankovic, J.; Pan, T. Resveratrol-activated AMPK/SIRT1/autophagy in cellular models of Parkinson’s disease. Neuro-Signals 2011, 19, 163–174.

- Outeiro, T.F.; Kontopoulos, E.; Altmann, S.M.; Kufareva, I.; Strathearn, K.E.; Amore, A.M.; Volk, C.B.; Maxwell, M.M.; Rochet, J.C.; McLean, P.J.; et al. Sirtuin 2 inhibitors rescue alpha-synuclein-mediated toxicity in models of Parkinson’s disease. Science 2007, 317, 516–519.

- Deng, C.X. SIRT1, is it a tumor promoter or tumor suppressor? Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2009, 5, 147–152.

- Alhazzazi, T.Y.; Kamarajan, P.; Verdin, E.; Kapila, Y.L. SIRT3 and cancer: Tumor promoter or suppressor? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1816, 80–88.

- Wang, B.; Ye, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, H.; Mustonen, H.; et al. SIRT2-dependent IDH1 deacetylation inhibits colorectal cancer and liver metastases. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e48183.

- Hu, A.; Yang, L.Y.; Liang, J.; Lu, D.; Zhang, J.L.; Cao, F.F.; Fu, J.Y.; Dai, W.J.; Zhang, J.F. SIRT2 modulates VEGFD-associated lymphangiogenesis by deacetylating EPAS1 in human head and neck cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2020, 59, 1280–1291.

- Hiratsuka, M.; Inoue, T.; Toda, T.; Kimura, N.; Shirayoshi, Y.; Kamitani, H.; Watanabe, T.; Ohama, E.; Tahimic, C.G.; Kurimasa, A.; et al. Proteomics-based identification of differentially expressed genes in human gliomas: Down-regulation of SIRT2 gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 309, 558–566.

- Michishita, E.; McCord, R.A.; Berber, E.; Kioi, M.; Padilla-Nash, H.; Damian, M.; Cheung, P.; Kusumoto, R.; Kawahara, T.L.; Barrett, J.C.; et al. SIRT6 is a histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylase that modulates telomeric chromatin. Nature 2008, 452, 492–496.

- Schug, T.T.; Li, X. Sirtuin 1 in lipid metabolism and obesity. Ann. Med. 2011, 43, 198–211.

- Horton, J.D.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. SREBPs: Activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 1125–1131.

- Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Blander, G.; Tse, J.G.; Krieger, M.; Guarente, L. SIRT1 deacetylates and positively regulates the nuclear receptor LXR. Mol. Cell 2007, 28, 91–106.

- Heikkinen, S.; Auwerx, J.; Argmann, C.A. PPARgamma in human and mouse physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1771, 999–1013.

- Kim, H.S.; Xiao, C.; Wang, R.H.; Lahusen, T.; Xu, X.; Vassilopoulos, A.; Vazquez-Ortiz, G.; Jeong, W.I.; Park, O.; Ki, S.H.; et al. Hepatic-specific disruption of SIRT6 in mice results in fatty liver formation due to enhanced glycolysis and triglyceride synthesis. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 224–236.

- Wang, F.; Tong, Q. SIRT2 suppresses adipocyte differentiation by deacetylating FOXO1 and enhancing FOXO1′s repressive interaction with PPARgamma. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 801–808.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cardiac & Cardiovascular Systems

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

844

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

20 Mar 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No