Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gah-Hyun Lim | -- | 1994 | 2023-03-08 12:41:15 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1994 | 2023-03-09 02:29:52 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Kim, T.; Lim, G. Salicylic Acid and Systemic Immunity in Plants. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41982 (accessed on 10 March 2026).

Kim T, Lim G. Salicylic Acid and Systemic Immunity in Plants. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41982. Accessed March 10, 2026.

Kim, Tae-Jin, Gah-Hyun Lim. "Salicylic Acid and Systemic Immunity in Plants" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41982 (accessed March 10, 2026).

Kim, T., & Lim, G. (2023, March 08). Salicylic Acid and Systemic Immunity in Plants. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41982

Kim, Tae-Jin and Gah-Hyun Lim. "Salicylic Acid and Systemic Immunity in Plants." Encyclopedia. Web. 08 March, 2023.

Copy Citation

Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) occurs when primary infected leaves produce several SAR-inducing chemical or mobile signals that are transported to uninfected distal parts via apoplastic or symplastic compartments and activate systemic immunity. The transport route of many chemicals associated with SAR is unknown.

glycerol-3-phosphate

SA transport

salicylic acid

1. Introduction

Salicylic acid (SA, 2-hydroxybenzoic acid) is an essential defense hormone in plants that accumulates upon a pathogen attack to induce local defense and systemic acquired resistance (SAR) [1][2]. Genetic analyses have revealed that genes related to SA biosynthesis, conjugation, accumulation, signaling, and crosstalk with other hormones have been characterized, providing insights into how the immune response is finely coordinated [3][4][5][6][7][8][9]. The effects of SA can change enzyme activity, increase defense genes, enhance several defense responses, and/or generate free radicals [10]. Moreover, the evidence that SA plays a role in signaling resistance has been corroborated by analyses of Arabidopsis and tobacco plants, which accumulate little or no SA due to the expression of the bacterial nahG gene, which encodes salicylate hydroxylase [11]. SA biosynthesis and its complex role in plant defense are not yet fully understood, despite extensive research over the past 30 years.

SAR provides long-lasting protection against secondary pathogen attacks by priming the plant’s defense response. SAR is triggered by an initial infection, and results in the activation of the plant’s defense response throughout the entire plant, even in tissues that are not yet infected. As a result of SAR, the plant is able to coordinate its defense response and respond appropriately to pathogen attacks, even in distant tissues. Although the identity of a specific mobile signal is unknown, numerous SAR-inducing chemicals have been identified, some of which are physically mobile, and some of which are volatile in nature. These include salicylic acid (SA) [12] and its derivative methyl SA (MeSA) [13], pipecolic acid (Pip) [14] and its derivative N-hydroxy Pip (NHP) [15], dehydroabietinal (DA) [16], free radicals, nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS) [17], azelaic acid (AzA) [18], glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) [19], pinene volatiles [20], and extracellular (e)NAD(P) [21]. Several proteins also play crucial roles in SAR, including cuticle formation proteins such as acyl carrier protein 4 (ACP4) and mosaic death 1 (MOD1) [22]; two plasmodesmata (PD)-located proteins, such as plasmodesmata localizing protein 1/5 (PDLP1/5) [23][24]; and lipid transfer proteins (LTPs), such as defective induced resistance 1 (DIR1) and AzA insensitive 1 (AZI1) [25][26].

2. Salicylic Acid and Systemic Acquired Resistance

2.1. SA Biosynthesis

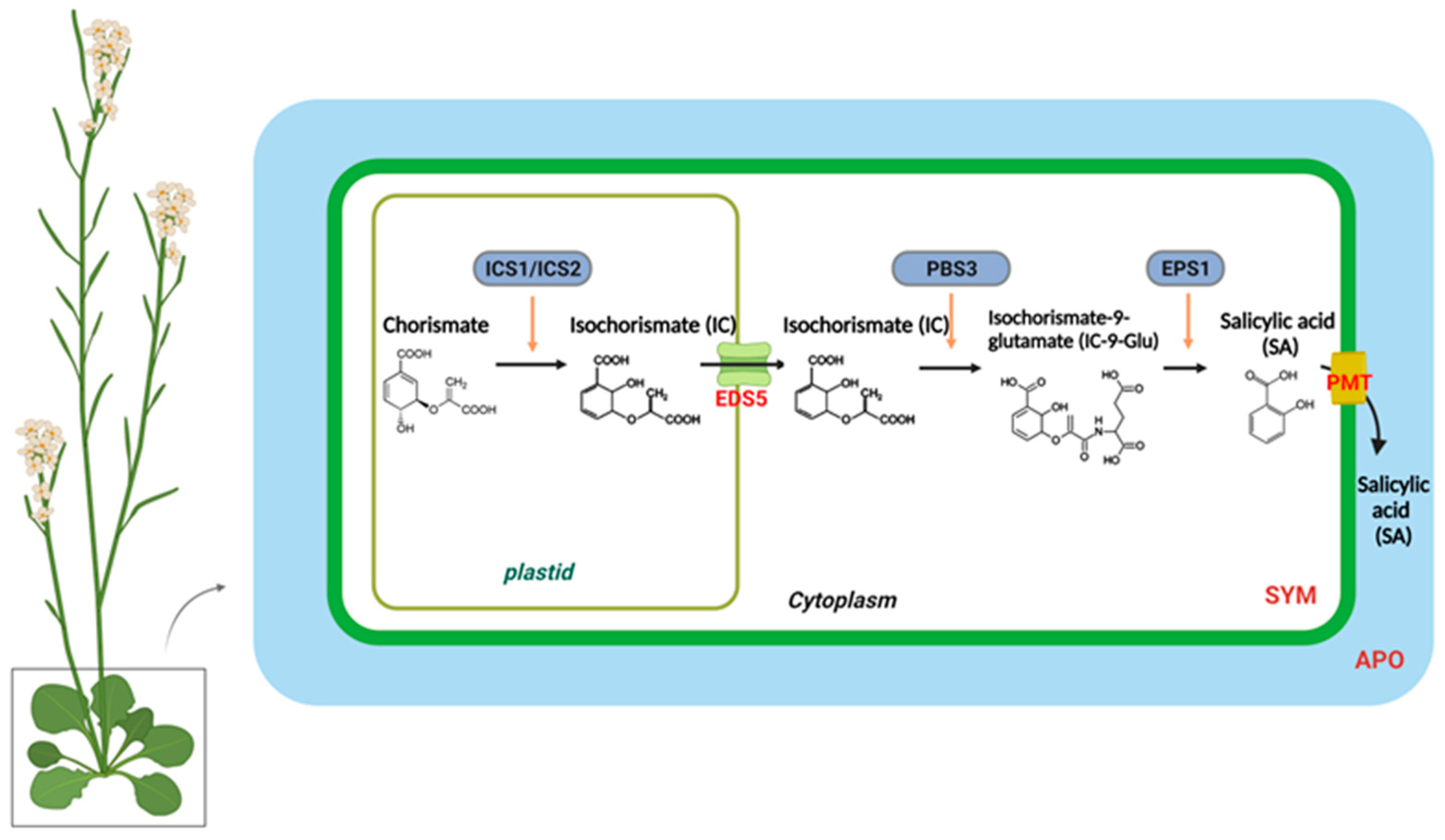

In higher plants, SA is synthesized from chorismate through two distinct metabolic pathways, each with multiple steps: the isochorismate synthase (ICS)- and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL)-derived pathways [27][28][29]. Different plant species have different branches toward SA biosynthesis. Pathogen infections in soybeans lead to equal contributions from the ICS and PAL pathways to the total pool of synthesized SA [29]. In Arabidopsis, the majority of pathogen-induced SA is derived from the ICS branch by plastid-localized ICS1 (also known as SA deficient 2 (SID2)) [30]. In Arabidopsis, there are two isochorismate synthase genes, ICS1 and ICS2; however, only ICS1 is induced by pathogens. The ics1 mutants showed 90–95% less SA accumulation after pathogen infection than wild-type plants [30]. Only the ics1/ics2 double mutant strongly affected SA accumulation, indicating that ICS1 generates most of the SA via isochorismate during pathogen defense. [8][31]. Several Arabidopsis mutants with altered SA accumulation are known to result from mutations in three genes encoding ICS pathway components. According to recent studies, bacteria have the Isochorismate Pyruvate Lyase (IPL) enzyme, which directly converts isochorismate to SA, whereas Arabidopsis requires both AvrPphB-susceptible 3 (PBS3) and Enhanced Pseudomonas Susceptibility 1 (EPS1) [29][32][33][34][35][36]. The amidotransferase PBS3 catalyzes the conjugation of isochorismate to glutamate, resulting in the formation of isochorismate-9-glutamate (IC-9-Glu). Subsequently, either IC-9-Glu can spontaneously decay into SA or convert into SA by EPS1. PBS3 and EPS1 are located in the cytosol, whereas ICS is localized in the chloroplasts [29]. Accordingly, the transport of isochorismate from plastids to the cytosol is essential for SA production. EDS5 (Enhanced Disease Susceptibility 5) was originally believed to act as a transporter of SA on the chloroplast envelope when pathogen-induced SA accumulation occurred [37][38]. However, in the eds5-3 mutants, co-expression of ICS1 and engineered chloroplast-targeted PBS3 can restore SA biosynthesis, suggesting that EDS5 could participate in isochorismate transport to the cytosol during SA biosynthesis [29].

A small amount of SA accumulation is induced by pathogens in the ics1/ics2 double mutant, which is blocked by the ICS pathway [32]. Arabidopsis contains four PAL genes, and studies with mutants or PAL-specific inhibitors suggest that the PAL pathway is also involved in SA biosynthesis [6][39]. Nevertheless, the PAL quadruple mutants still have approximately 25% of the wild-type basal SA levels and approximately 50% of the induced SA levels following pathogen infection [39]. The PAL pathway involves trans-cinnamic acid synthesized from phenylalanine, which is then converted to SA via benzoic acid [40] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The biosynthesis and transport of salicylic acid in a plant cell. In plastids, chorismite is converted to isochorismate (IC) through the action of an IsoChorismate Synthase (ICS1/2). A MATE transporter called Enhanced Disease Susceptibility 5 (EDS5) transports IC from the plastid to the cytosol. The AvrPphB susceptible 3 (PBS3) catalyzes the conjugation of IC to glutamate (Glu), which results in IsoChorismate-9-Glutamate (IC-9-Glu). IC-9-Glu is then converted to salicylic acid (SA) by Enhanced Pseudomonas Susceptibility 1 (EPS1). SA moves preferentially to the apoplastic compartment (APO) through the plasma membrane transporter (PMT).

2.2. Regulation of SA Biosynthesis

The expression of ICS1 is rapidly induced upon pathogen infection, which dramatically increases the SA levels. In recent reviews [2][41], a large number of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulators were identified that affect ICS1. Furthermore, EDS5 and PBS3 were strongly induced during infection. These three SA biosynthesis genes, as well as a number of immune regulator genes, are controlled by the transcription factors SAR-Deficient 1 (SARD1) and Calmodulin-Binding Protein 60-Like.g (CBP60g) [42]. The transcription of SARD1 and CBP60g is stimulated by TGACG-Binding Factors1 (TGA1) and TGA4, respectively, whereas the negative immune regulators Calmodulin-Binding Transcription Factor 1 (CAMTA1), CAMTA2, and CAMT3 inhibit their transcription by inhibiting expression [43]. In addition, a pathogen induces the expression of ICS1, EDS5, and PBS3 by binding to its promoter with CBP60g, and is homologous to SARD1 [44]. The cbp60g sard1 double mutant impairs ICS1, EDS5, and PBS3 induction and, subsequently, SA biosynthesis by bacterial elicitor flg22 or the avirulent bacterial strain Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicola (Psm) ES4326 avrB, resulting in compromised pattern-triggered immunity (PTI)- and effector-triggered immunity (ETI)-induced resistance as well as SAR [45][46]. Mutants defective in EDS5 show impaired SA accumulation and resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) DC3000 [8]. Likewise, pbs3 mutants display reduced SA accumulation in response to pathogens, such as plants with defects in ICS1 and EDS5. Additionally, several proteins contribute to SA accumulation and SAR in response to pathogens. These include Enhanced Disease Susceptibility 1 (EDS1), Phytoalexin Deficient 4 (PAD4), and Non-race-specific Disease Resistance 1 (NDR1), which show partial reductions in SA levels, unlike ICS1 and EDS5 [47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58].

3. Mobile Inducers of SAR

3.1. Biosynthesis of G3P and AzA in SAR

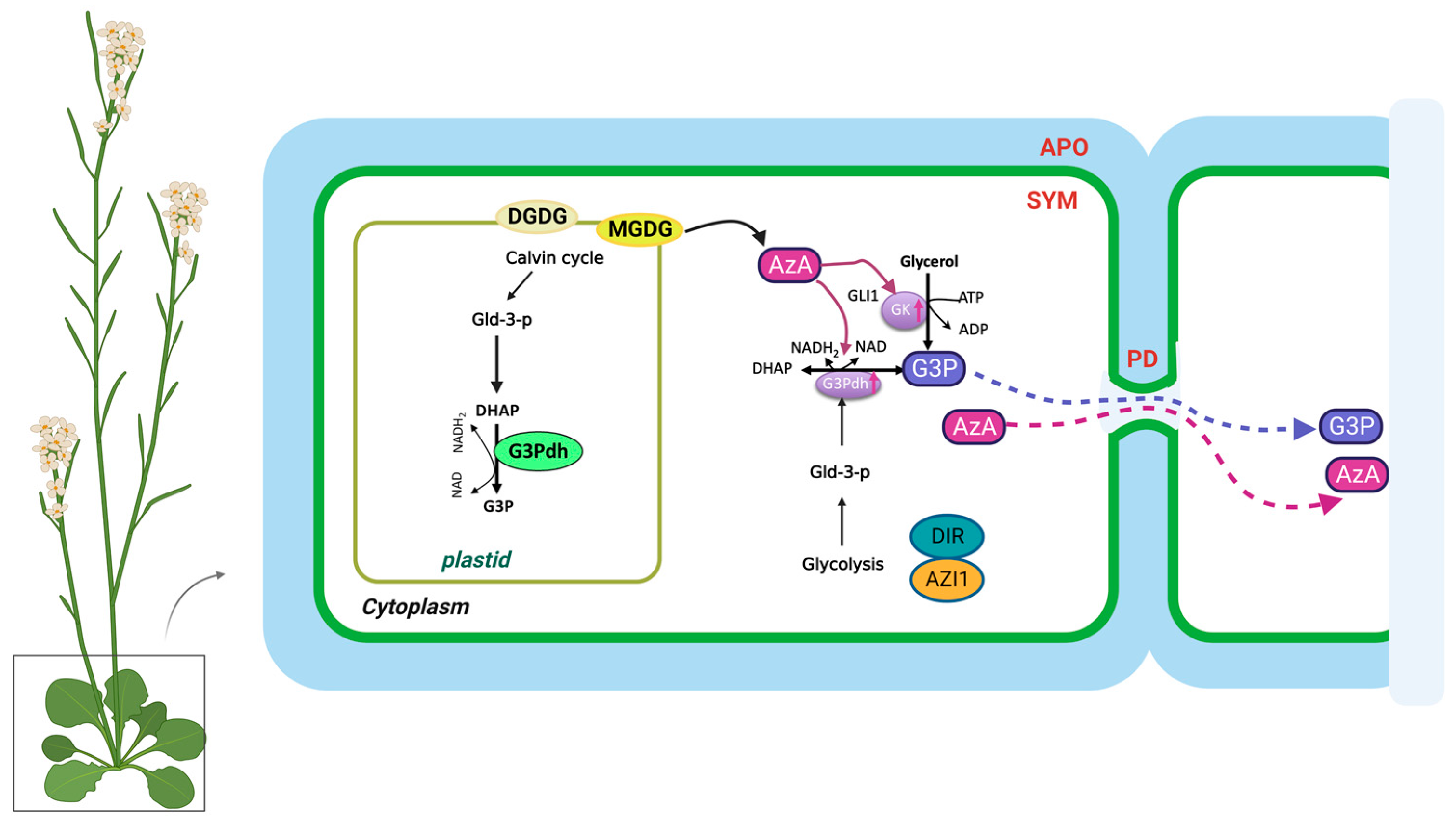

Pathogen infections result in rapid NO accumulation during SAR via unknown mechanisms. NO application did not confer SAR to Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homologs (RBOH) mutants rbohD and rbohF, indicating that ROS radicals function downstream of NO in SAR [21]. As a result of pathogen infection, these mutants do not accumulate superoxide radicals. There is no redundancy between rbohD and rbohF, and mutation in either of them compromises SAR. Nevertheless, exogenous ROS application restored SAR in NO associated protein 1 (noa1)/nitrate reductases 1 (nia1) or the noa1/nia2 double mutants, which were deficient in NO [59]. Plants infected with pathogens accumulate AzA up to six-fold more in petiole exudates, and at least some of this AzA translocates to the distal tissues (up to 7%) [18][26]. A pathogen infection releases free FAs from membrane lipids that are hydrolyzed by ROS to generate AzA. Plant lipids digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) and monogalatosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) contain C18 FAs that are catalyzed by different ROS species [60]. In particular, AzA is formed by cleaving the double bonds between carbons 9 and 10 of C18 unsaturated FAs, including oleic (18:1), linoleic (18:2), and linolenic acids (18:3) [24]. G3P is a phosphorylated metabolite of glycerol that plays a crucial role in lipid metabolism. The biosynthesis of G3P in plants takes place mainly during photosynthesis. Some of the glucose produced is then converted into G3P through a series of metabolic reactions. G3P is synthesized from dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) by triose phosphate isomerase (TPI) [19]. Exogenous AzA increased the expression of the G3P biosynthesis genes GLY1 (G3P dehydrogenase, G3PDH) and GLI1 (glycerol kinase, GK), resulting in G3P accumulation [19]. Exogenous G3P causes resistance to Colletotrichum higginsianum and induces SAR in Arabidopsis and monocots [19][61]. Interestingly, plants do not accumulate SA following exogenous G3P and AzA administration, which induce SAR in wild-type plants. Despite this, neither G3P nor AzA is able to confer SAR in ics1(sid2) mutant plants, which have significantly reduced either basal or pathogen-induced SA levels [19]. As a result, SA is essential for establishing SAR, but the accumulation of SA alone is not sufficient. A defect in G3P synthesis in gly1 and gli1 mutant plants resulted in a compromised SAR phenotype, which could be restored by exogenous G3P application [19][26]. Intriguingly, gly1 and gli1 mutants exhibited levels of SA and AzA similar to those in the wild-type plants. Additionally, exogenous application of G3P alone was not sufficient to induce SA biosynthesis or SAR. These results suggest that, similarly to SA, AzA and G3P may not be sufficient to induce SAR.

3.2. Regulation of G3P and AzA Transport in SAR

In the presence of DIR1, G3P is systemically mobile, but its direct binding has not yet been identified [26]. DIR1 is likely to be directly associated with this bioactive G3P-derivative, and upon translocation to distal tissues, induces SAR in response to pathogen infection. SAR does not seem to be associated with AzA transport, which may be explained by its independence from DIR1, AZI1, GLY1, GLI1, or exogenous G3P [26]. In contrast to SA, G3P and AzA are preferentially transported from local to distal leaves through the PD, and defects in PD permeability affect their transport (Figure 2). Thus, PD-localizing proteins (PDLPs) not only regulate PD permeability, thereby controlling AzA and G3P transport, but also signal through the SAR [23]. Plants overexpressing PDLP5 have impaired AzA and G3P transport, as well as compromised SAR. In addition, 35S-PDLP5-expressing plants show reduced transport of DIR1, a lipid-transfer protein involved in SAR [23][24]. The lipid transfer-like protein AZI1, an important component of the SAR pathway, is also regulated by PDLP1 and PDLP5 [23]. Thus, SAR was impaired in both pdlp1 and pdlp5 mutant plants, but only pdlp5 plants showed an increase in PD permeability. As AZI1 interacts with both PDLP1 and PDLP5, it is likely to form complexes with both proteins. Loss of PDLP1 or PDLP5 increases the chloroplastic localization of AZI1, although the biological significance of the chloroplastic localization of AZI1 or its intracellular partitioning during SAR is not known [23][62]. Therefore, understanding how AzA functions in subcellular compartments is crucial to understanding SAR. G3P and AzA, which induce SAR in wild-type plants, do not induce SA accumulation in plants. In spite of this, neither G3P nor AzA can confer SAR in ics1(sid2) mutant plants, which have significantly reduced either basal or pathogen-induced SA levels.

Figure 2. The biosynthesis and transport of azelaic acid and glycerol-3-phosphate in the plant cell. AzA and G3P are transported via the symplast through plasmodesmata (PD). AZA induces G3P biosynthesis through its effects on genes involved in SAR. DIR1 and AZI1, both of which depend on G3P for stability, are required for G3P-mediated SAR signaling. G3P is either converted to glycerol by G3P phosphatase or used to synthesize membrane lipids (glycerolipids) and triacylglycerol (TAG). The source of DHAP is glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (Gld-3-P), which originates from glycolysis and the Calvin cycle. DGDG, galactolipid digalactosyldiacylglycerol; MGDG, monogalatosyldiacylglycerol; AzA, azelaic acid; G3P, glycerol-3-phosphate; Gld-3-P, Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate; DHAP, DHA phosphate; GK, glycerol kinase; G3Pdh, G3P dehydrogenase; DIR1, Defective Induced Resistance 1; AZI1, AzA Insensitive 1 (AZI1).

References

- Vlot, A.C.; Dempsey, D.M.A.; Klessig, D.F. Salicylic acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2009, 47, 177–206.

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Salicylic acid: Biosynthesis, perception, and contributions to plant immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 50, 29–36.

- Dempsey, D.M.A.; Vlot, A.C.; Wildermuth, M.C.; Klessig, D.F. Salicylic acid biosynthesis and metabolism. Arab. Book/Am. Soc. Plant Biol. 2011, 9, e0156.

- Gaffney, T.; Friedrich, L.; Vernooij, B.; Negrotto, D.; Nye, G.; Uknes, S.; Ward, E.; Kessmann, H.; Ryals, J. Requirement of salicylic acid for the induction of systemic acquired resistance. Science 1993, 261, 754–756.

- Delaney, T.P.; Uknes, S.; Vernooij, B.; Friedrich, L.; Weymann, K.; Negrotto, D.; Gaffney, T.; Gut-Rella, M.; Kessmann, H.; Ward, E.; et al. A central role of salicylic acid in plant disease resistance. Science 1994, 266, 1247–1250.

- Mauch-Mani, B.; Slusarenko, A.J. Production of salicylic acid precursors is a major function of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase in the resistance of Arabidopsis to Peronospora parasitica. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 203–212.

- Pallas, J.A.; Paiva, N.L.; Lamb, C.; Dixon, R.A. Tobacco plants epigenetically suppressed in phenylalanine ammonia-lyase expression do not develop systemic acquired resistance in response to infection by tobacco mosaic virus. Plant J. 1996, 10, 281–293.

- Nawrath, C.; Métraux, J.-P. Salicylic acid induction–deficient mutants of Arabidopsis express PR-2 and PR-5 and accumulate high levels of camalexin after pathogen inoculation. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 1393–1404.

- Dewdney, J.; Reuber, T.L.; Wildermuth, M.C.; Devoto, A.; Cui, J.; Stutius, L.M.; Drummond, E.P.; Ausubel, F.M. Three unique mutants of Arabidopsis identify eds loci required for limiting growth of a biotrophic fungal pathogen. Plant J. 2000, 24, 205–218.

- Dempsey, D.M.A.; Klessig, D.F. SOS–too many signals for systemic acquired resistance? Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 538–545.

- Vernooij, B.; Friedrich, L.; Morse, A.; Reist, R.; Kolditz-Jawhar, R.; Ward, E.; Uknes, S.; Kessmann, H.; Ryals, J. Salicylic acid is not the translocated signal responsible for inducing systemic acquired resistance but is required in signal transduction. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 959–965.

- Shah, J.; Chaturvedi, R.; Chowdhury, Z.; Venables, B.; Petros, R.A. Signaling by small metabolites in systemic acquired resistance. Plant J. 2014, 79, 645–658.

- Park, S.-W.; Kaimoyo, E.; Kumar, D.; Mosher, S.; Klessig, D.F. Methyl salicylate is a critical mobile signal for plant systemic acquired resistance. Science 2007, 318, 113–116.

- Návarová, H.; Bernsdorff, F.; Döring, A.-C.; Zeier, J. Pipecolic acid, an endogenous mediator of defense amplification and priming, is a critical regulator of inducible plant immunity. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 5123–5141.

- Hartmann, M.; Zeier, J. l-lysine metabolism to N-hydroxypipecolic acid: An integral immune-activating pathway in plants. Plant J. 2018, 96, 5–21.

- Chaturvedi, R.; Venables, B.; Petros, R.A.; Nalam, V.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Takemoto, L.J.; Shah, J. An abietane diterpenoid is a potent activator of systemic acquired resistance. Plant J. 2012, 71, 161–172.

- Wang, C.; El-Shetehy, M.; Shine, M.; Yu, K.; Navarre, D.; Wendehenne, D.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Free radicals mediate systemic acquired resistance. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 348–355.

- Jung, H.W.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Wang, L.; Glazebrook, J.; Greenberg, J.T. Priming in systemic plant immunity. Science 2009, 324, 89–91.

- Chanda, B.; Xia, Y.; Mandal, M.K.; Yu, K.; Sekine, K.T.; Gao, Q.-m.; Selote, D.; Hu, Y.; Stromberg, A.; Navarre, D. Glycerol-3-phosphate is a critical mobile inducer of systemic immunity in plants. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 421–427.

- Riedlmeier, M.; Ghirardo, A.; Wenig, M.; Knappe, C.; Koch, K.; Georgii, E.; Dey, S.; Parker, J.E.; Schnitzler, J.-P.; Vlot, A.C. Monoterpenes support systemic acquired resistance within and between plants. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1440–1459.

- Sagi, M.; Fluhr, R. Production of reactive oxygen species by plant NADPH oxidases. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 336–340.

- Xia, Y.; Gao, Q.-M.; Yu, K.; Lapchyk, L.; Navarre, D.; Hildebrand, D.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. An intact cuticle in distal tissues is essential for the induction of systemic acquired resistance in plants. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 151–165.

- Lim, G.-H.; Shine, M.; de Lorenzo, L.; Yu, K.; Cui, W.; Navarre, D.; Hunt, A.G.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Plasmodesmata localizing proteins regulate transport and signaling during systemic acquired immunity in plants. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 541–549.

- Carella, P.; Isaacs, M.; Cameron, R. Plasmodesmata-located protein overexpression negatively impacts the manifestation of systemic acquired resistance and the long-distance movement of Defective in Induced Resistance1 in A rabidopsis. Plant Biol. 2015, 17, 395–401.

- Maldonado, A.M.; Doerner, P.; Dixon, R.A.; Lamb, C.J.; Cameron, R.K. A putative lipid transfer protein involved in systemic resistance signalling in Arabidopsis. Nature 2002, 419, 399–403.

- Yu, K.; Soares, J.M.; Mandal, M.K.; Wang, C.; Chanda, B.; Gifford, A.N.; Fowler, J.S.; Navarre, D.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. A feedback regulatory loop between G3P and lipid transfer proteins DIR1 and AZI1 mediates azelaic-acid-induced systemic immunity. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1266–1278.

- Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Biosynthesis and regulation of salicylic acid and N-hydroxypipecolic acid in plant immunity. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 31–41.

- Wildermuth, M.C.; Dewdney, J.; Wu, G.; Ausubel, F.M. Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature 2001, 414, 562–565.

- Rekhter, D.; Lüdke, D.; Ding, Y.; Feussner, K.; Zienkiewicz, K.; Lipka, V.; Wiermer, M.; Zhang, Y.; Feussner, I. Isochorismate-derived biosynthesis of the plant stress hormone salicylic acid. Science 2019, 365, 498–502.

- Gao, Q.-m.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Chemical inducers of systemic immunity in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1849–1855.

- Garcion, C.; Lohmann, A.; Lamodière, E.; Catinot, J.; Buchala, A.; Doermann, P.; Métraux, J.-P. Characterization and biological function of the ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE2 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1279–1287.

- Mercado-Blanco, J.S.; van der Drift, K.M.; Olsson, P.E.; Thomas-Oates, J.E.; van Loon, L.C.; Bakker, P.A. Analysis of the pmsCEAB gene cluster involved in biosynthesis of salicylic acid and the siderophore pseudomonine in the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS374. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 1909–1920.

- Jagadeeswaran, G.; Raina, S.; Acharya, B.R.; Maqbool, S.B.; Mosher, S.L.; Appel, H.M.; Schultz, J.C.; Klessig, D.F.; Raina, R. Arabidopsis GH3-LIKE DEFENSE GENE 1 is required for accumulation of salicylic acid, activation of defense responses and resistance to Pseudomonas syringae. Plant J. 2007, 51, 234–246.

- Lee, M.W.; Lu, H.; Jung, H.W.; Greenberg, J.T. A key role for the Arabidopsis WIN3 protein in disease resistance triggered by Pseudomonas syringae that secrete AvrRpt2. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 1192–1200.

- Nobuta, K.; Okrent, R.; Stoutemyer, M.; Rodibaugh, N.; Kempema, L.; Wildermuth, M.; Innes, R. The GH3 acyl adenylase family member PBS3 regulates salicylic acid-dependent defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 1144–1156.

- Torrens-Spence, M.P.; Bobokalonova, A.; Carballo, V.; Glinkerman, C.M.; Pluskal, T.; Shen, A.; Weng, J.-K. PBS3 and EPS1 complete salicylic acid biosynthesis from isochorismate in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 1577–1586.

- Nawrath, C.; Heck, S.; Parinthawong, N.; Métraux, J.-P. EDS5, an essential component of salicylic acid–dependent signaling for disease resistance in Arabidopsis, is a member of the MATE transporter family. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 275–286.

- Serrano, M.; Wang, B.; Aryal, B.; Garcion, C.; Abou-Mansour, E.; Heck, S.; Geisler, M.; Mauch, F.; Nawrath, C.; Métraux, J.-P. Export of salicylic acid from the chloroplast requires the multidrug and toxin extrusion-like transporter EDS5. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1815–1821.

- Huang, J.; Gu, M.; Lai, Z.; Fan, B.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Yu, J.-Q.; Chen, Z. Functional analysis of the Arabidopsis PAL gene family in plant growth, development, and response to environmental stress. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1526–1538.

- Yalpani, N.; León, J.; Lawton, M.A.; Raskin, I. Pathway of salicylic acid biosynthesis in healthy and virus-inoculated tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1993, 103, 315–321.

- Peng, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic acid: Biosynthesis and signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 761–791.

- Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y. ChIP-seq reveals broad roles of SARD1 and CBP60g in regulating plant immunity. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10159.

- Sun, T.; Huang, J.; Xu, Y.; Verma, V.; Jing, B.; Sun, Y.; Orduna, A.R.; Tian, H.; Huang, X.; Xia, S. Redundant CAMTA transcription factors negatively regulate the biosynthesis of salicylic acid and N-hydroxypipecolic acid by modulating the expression of SARD1 and CBP60g. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 144–156.

- Truman, W.; Glazebrook, J. Co-expression analysis identifies putative targets for CBP60g and SARD1 regulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 216.

- Wang, L.; Tsuda, K.; Truman, W.; Sato, M.; Nguyen, L.V.; Katagiri, F.; Glazebrook, J. CBP60g and SARD1 play partially redundant critical roles in salicylic acid signaling. Plant J. 2011, 67, 1029–1041.

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Ding, P.; Wang, D.; Cheng, Y.T.; He, J.; Gao, M.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Control of salicylic acid synthesis and systemic acquired resistance by two members of a plant-specific family of transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18220–18225.

- Century, K.S.; Holub, E.B.; Staskawicz, B.J. NDR1, a locus of Arabidopsis thaliana that is required for disease resistance to both a bacterial and a fungal pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 6597–6601.

- Falk, A.; Feys, B.J.; Frost, L.N.; Jones, J.D.; Daniels, M.J.; Parker, J.E. EDS1, an essential component of R gene-mediated disease resistance in Arabidopsis has homology to eukaryotic lipases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3292–3297.

- Jirage, D.; Tootle, T.L.; Reuber, T.L.; Frost, L.N.; Feys, B.J.; Parker, J.E.; Ausubel, F.M.; Glazebrook, J. Arabidopsis thaliana PAD4 encodes a lipase-like gene that is important for salicylic acid signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13583–13588.

- McDowell, J.M.; Dangl, J.L. Signal transduction in the plant immune response. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 79–82.

- Feys, B.J.; Moisan, L.J.; Newman, M.-A.; Parker, J.E. Direct interaction between the Arabidopsis disease resistance signaling proteins, EDS1 and PAD4. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 5400–5411.

- Coppinger, P.; Repetti, P.P.; Day, B.; Dahlbeck, D.; Mehlert, A.; Staskawicz, B.J. Overexpression of the plasma membrane-localized NDR1 protein results in enhanced bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2004, 40, 225–237.

- Ishihara, T.; Sekine, K.T.; Hase, S.; Kanayama, Y.; Seo, S.; Ohashi, Y.; Kusano, T.; Shibata, D.; Shah, J.; Takahashi, H. Overexpression of the Arabidopsis thaliana EDS5 gene enhances resistance to viruses. Plant Biol. 2008, 10, 451–461.

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Halane, M.K.; Kim, S.H.; Gassmann, W. Pathogen effectors target Arabidopsis EDS1 and alter its interactions with immune regulators. Science 2011, 334, 1405–1408.

- Cacas, J.-L.; Petitot, A.-S.; Bernier, L.; Estevan, J.; Conejero, G.; Mongrand, S.; Fernandez, D. Identification and characterization of the Non-race specific Disease Resistance 1 (NDR1) orthologous protein in coffee. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 144.

- Heidrich, K.; Wirthmueller, L.; Tasset, C.; Pouzet, C.; Deslandes, L.; Parker, J.E. Arabidopsis EDS1 connects pathogen effector recognition to cell compartment–specific immune responses. Science 2011, 334, 1401–1404.

- Knepper, C.; Savory, E.A.; Day, B. Arabidopsis NDR1 is an integrin-like protein with a role in fluid loss and plasma membrane-cell wall adhesion. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 286–300.

- Zhang, P.-J.; Li, W.-D.; Huang, F.; Zhang, J.-M.; Xu, F.-C.; Lu, Y.-B. Feeding by whiteflies suppresses downstream jasmonic acid signaling by eliciting salicylic acid signaling. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013, 39, 612–619.

- El-Shetehy, M.; Wang, C.; Shine, M.; Yu, K.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species are required for systemic acquired resistance in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e998544.

- Gao, Q.-m.; Yu, K.; Xia, Y.; Shine, M.; Wang, C.; Navarre, D.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Mono-and digalactosyldiacylglycerol lipids function nonredundantly to regulate systemic acquired resistance in plants. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 1681–1691.

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, P.; Xing, H.; Li, C.; Wei, G.; Kang, Z. Glycerol-3-phosphate metabolism in wheat contributes to systemic acquired resistance against Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81756.

- Wendehenne, D.; Gao, Q.-m.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Free radical-mediated systemic immunity in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 20, 127–134.

More

Information

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.7K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

09 Mar 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No