Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Joseph El Dahdah | -- | 1702 | 2023-03-02 17:18:49 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1702 | 2023-03-03 02:15:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Arockiam, A.D.; Agrawal, A.; El Dahdah, J.; Honnekeri, B.; Kafil, T.S.; Halablab, S.; Griffin, B.P.; Wang, T.K.M. Echocardiography of Infective Endocarditis. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41826 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Arockiam AD, Agrawal A, El Dahdah J, Honnekeri B, Kafil TS, Halablab S, et al. Echocardiography of Infective Endocarditis. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41826. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Arockiam, Aro Daniela, Ankit Agrawal, Joseph El Dahdah, Bianca Honnekeri, Tahir S. Kafil, Saleem Halablab, Brian P. Griffin, Tom Kai Ming Wang. "Echocardiography of Infective Endocarditis" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41826 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Arockiam, A.D., Agrawal, A., El Dahdah, J., Honnekeri, B., Kafil, T.S., Halablab, S., Griffin, B.P., & Wang, T.K.M. (2023, March 02). Echocardiography of Infective Endocarditis. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41826

Arockiam, Aro Daniela, et al. "Echocardiography of Infective Endocarditis." Encyclopedia. Web. 02 March, 2023.

Copy Citation

Infective endocarditis (IE) refers to an infection of the endocardial surface structures of the heart. It is a complex heterogeneous condition often with systemic complications and carries a high rate of mortality and morbidities.

infective endocarditis

multi-modality imaging

echocardiography

1. Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) refers to an infection of the endocardial surface structures of the heart [1][2]. It is a complex heterogeneous condition often with systemic complications and carries a high rate of mortality and morbidities. The diagnosis of IE is traditionally based on the modified Duke criteria, but remains challenging in many clinical scenarios, and delayed diagnosis may lead to irreversible harm to patients [3]. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the first-line imaging modality for assessing IE, and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is required in the vast majority. Computed tomography (CT), nuclear imaging such as 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG-PET/CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) are increasingly utilized as complimentary cardiovascular imaging techniques for identifying IE and its complications, with several niche indications. Together, multi-modality cardiac imaging plays a critical role in the evaluation and treatment guidance of IE towards medical and surgical therapies.

2. Echocardiography

2.1. Transthoracic Echocardiography

Echocardiography is the cornerstone of imaging modalities used for IE assessment [4]. The modified Duke criteria, which indicate whether definitive infection or probable infection is present according to major and minor criteria, have major echocardiographic criteria for IE diagnosis that include vegetations, abscesses, new valvular regurgitation, and prosthesis dehiscence, while other supporting features include valve perforation or aneurysm [1]. TTE is the first-line imaging test for IE and should be promptly performed as soon as IE is suspected [1][5][6][7]. A complete examination should be performed, involving all standard parasternal, apical, subcostal, and suprasternal views, and employing two-dimensional, Doppler, and three-dimensional techniques with careful interrogation on all four heart valves, including prosthetic heart valves and cardiac devices, as well as the aorta for signs of IE [8]. TTE can also assess the cardiac chamber’s size and function, as well as evaluating for congenital heart disease, pericardial conditions, adjacent vascular structures, and estimating pulmonary pressures. All echocardiography techniques excel with high temporal resolution, so they are generally better at identifying mobile vegetations, especially if they are small or thin compared to other modalities. TTE has many strengths, such as it being a first-line imaging modality, but with notable limitations, such as suboptimal sensitivity due to lower spatial resolution and prosthetic valve artifacts warranting further evaluation [6][9], as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1. Strengths and limitations of multi-modality imaging for evaluating infective endocarditis.

| Imaging Modality | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) | Widely available, first-line modality, safe with no radiation exposure, portable, high temporal resolution, assesses hemodynamics, valve function, endocarditis features, and chamber function. | Operator and patient dependent on imaging windows, creates artifacts, lower sensitivity than more advanced modalities in identifying most endocarditis features including small vegetations, periannular complications, prosthetic valve, and device-related endocarditis. |

| Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) | Portable, higher sensitivity than TTE for most endocarditis features, preferred modality for vegetations, valve perforation, prosthetic valve dehiscence and paravalvular leak, identifies fistula, high spatial and temporal resolution. | Invasive imaging modality, may still have artifact and lower sensitivity for some prosthetic valves and cardiac devices, avoid in contraindications such as prior gastroesophageal disease and surgery, active bleeding, patient intolerance. |

| Cardiac CT | Short study, excellent for detection of perivalvular complications (pseudoaneurysm, abscess, and fistula) in all types of endocarditis, can also identify other endocarditis features, detect extracardiac complications, high spatial resolution, use for pre-operative workup, and assesses coronaries and major vessels. | Non-portable, lower sensitivity than echocardiography for smaller vegetations, perforations, and paravalvular leaks. Inferior temporal resolution to echocardiography, radiation exposure, iodinated contrast administration (avoid in chronic renal impairment, especially when creatinine clearance below 30). |

| Cardiac Magnetic Resonance | Can identify endocarditis complications in some scenarios, such as using its high sensitivity for cerebral lesions. Reference standard for chamber quantification and can also quantify valve disease and shunts (such as for fistula). | Long study, non-portable, can cause claustrophobia, cost, non-compatible devices, lower temporal resolution than echocardiography, only for stable patients who can lie flat and follow instructions. |

| 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) | Improved sensitivity for prosthetic valve and device-related endocarditis in some scenarios. | Non-portable, low sensitivity for native valve endocarditis, no functional cine imaging, radiation exposure, special pre-test preparation, cost, false-positive results within 3 months after cardiac surgery, false-negative results in patients treated with antimicrobials. |

2.2. Transesophageal Echocardiography

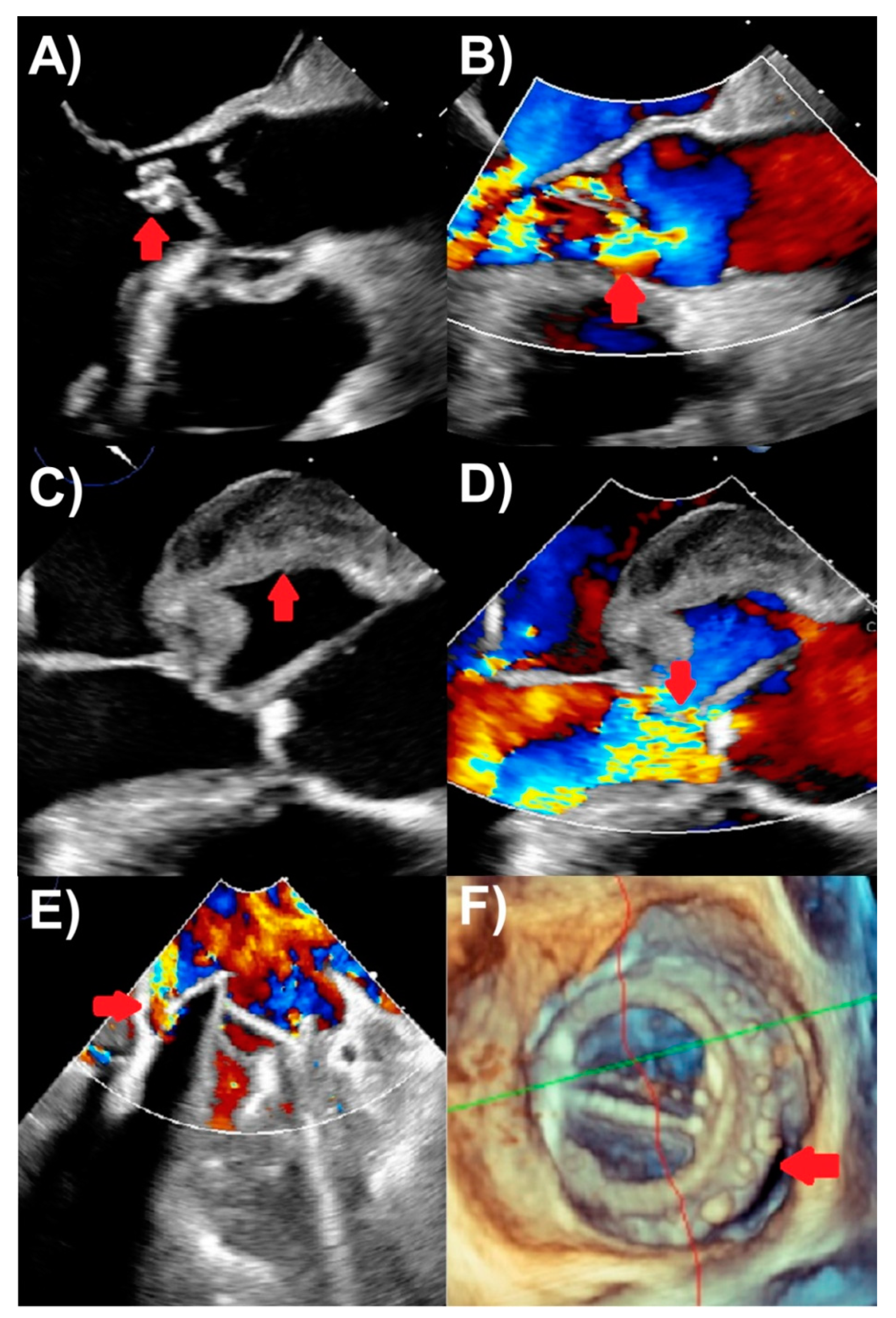

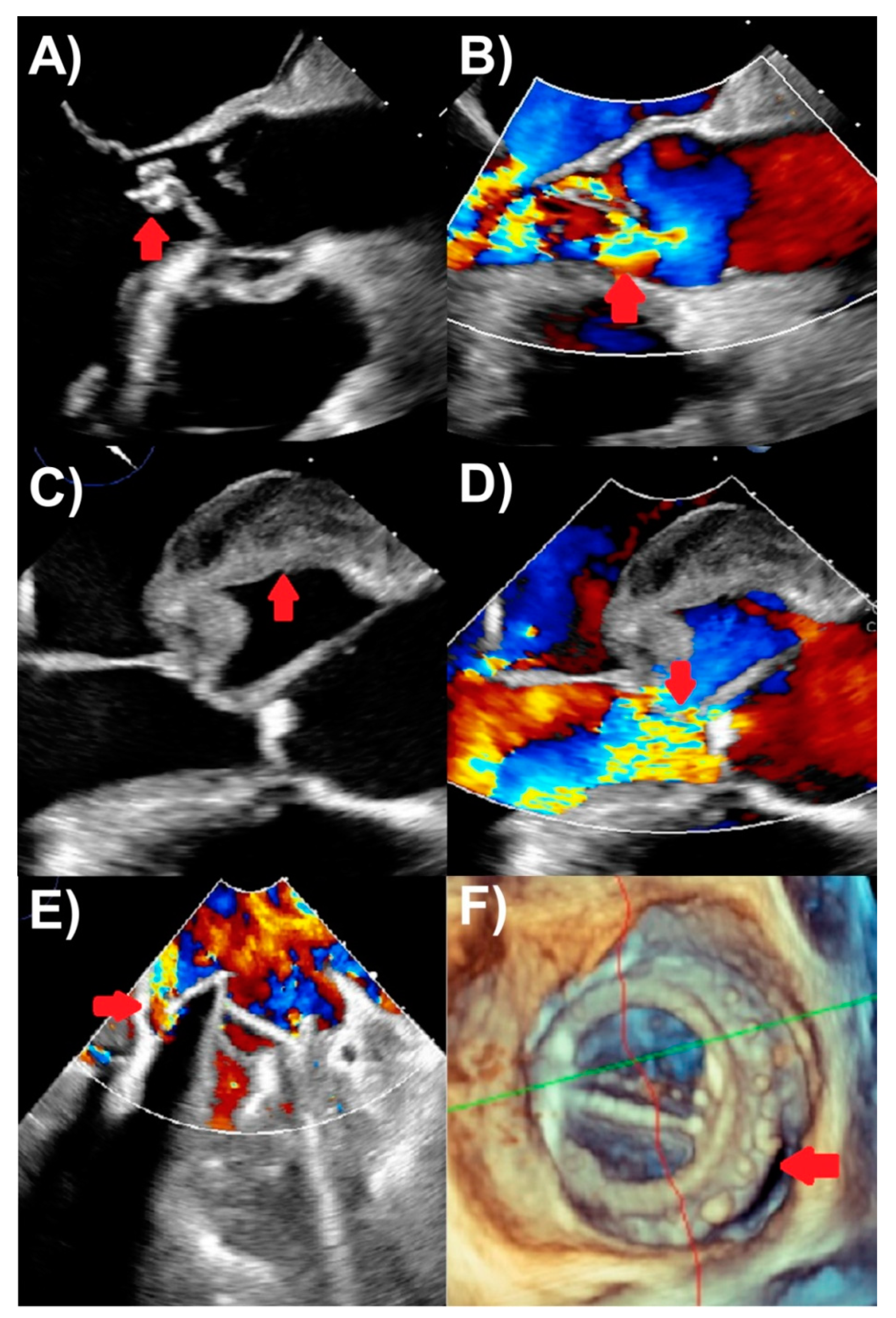

TEE is recommended for the vast majority of IE patients in absence of contraindications, because of its superior sensitivity and specificity to TTE from high spatial and comparable high temporal resolutions [10][11]. TEE is the best modality for evaluating vegetations, valve perforation, and prosthetic valve dehiscence, also performing well to identify pseudoaneurysm, abscesses, and fistulas (Figure 1). A comprehensive TEE examination should also be performed when assessing for IE, focusing on all four heart valves in esophageal and transgastric views [8]. In particular, contemporary three-dimensional echocardiography, including multi-planar reconstruction, is critical for the accurate depiction of the presence of IE, for its etiology and features, and usually more accurate for TEE than TTE. Clinical scenarios to use TEE include when TTE is inconclusive for IE, but there is a moderate-to-high clinical suspicion for IE; TTE is negative, but there is ongoing high clinical suspicion for IE; and TTE showing features of IE, but further evaluation for complications (such as new heart murmur, high-grade heart block, suspected abscess, embolic events, and heart failure) is required [1][2]. The last of these indications makes an argument for routinely performing TEE in all patients with IE, as TTE may miss important IE complications. TEE also plays an important role in assessing patients with prosthetic valves or intracardiac devices where TTE is less accurate and more prone to artifacts. TEE is not usually required if IE suspicion is low and TTE is negative [2]. Finally, intraoperative TEE is used for patients undergoing IE surgery to assess the extent of IE complications and the surgery needed, as well as for assessing the surgical result [1]. TTE and TEE are the cornerstones of first-line imaging modalities to assess endocarditis in all IE guidelines [1][2][12].

Figure 1. Transesophageal echocardiography findings of endocarditis. (A) Aortic valve vegetation (arrow), with (B) severe aortic regurgitation (arrow) on color Doppler. (C) Aortic with echolucent space consistent with pseudoaneurysm and abscess (arrow), with (D) severe aortic regurgitation (arrow) on color Doppler. (E) Mechanical mitral valve replacement paravalvular regurgitation (arrow) associated with (F) prosthetic valve dehiscence (arrow) seen on three-dimensional assessment.

2.3. Three-Dimensional Echocardiography

Three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography is now a cornerstone technique routinely performed in both TTE and TEE, including for the assessment of IE. The three-dimensional aspect has added value for many reasons in IE assessment, including when two-dimension echocardiography findings remain uncertain, since they enable more accurate anatomical delineation, localization of pathology, and measurement via multi-planar reconstruction. Real time 3D TEE permits the assessment of the 3D volumes of cardiac anatomy in infinite planes [13]. It is able to analyze vegetation size, morphological appearance, and embolic risk, and evaluate perivalvular extensions, valve perforations, and prosthetic valve dehiscence [14][15]. Furthermore, it has a valuable role especially with TEE in the intraprocedural guidance of surgical and transcatheter interventions. Limitations of 3D include dependence on the imaging quality of the 2D data and a lower spatial and temporal resolution restricting its application for small or highly mobile vegetations [16].

2.4. Comparisons of Echocardiography Modalities

Table 2 lists sensitivities and specificities of TTE, TEE, and other cardiac imaging modalities in identifying IE features, while stress echocardiography do not have a routine role in IE assessment. Overall, the TTE and TEE sensitivities for native valve IE were 40–60% and 90–100% respectively, and for prosthetic valve IE were 17–36% and 82–96%, respectively [4][8][10]. In particular, TTE and TEE sensitivities for vegetations were 44–69% and 87–100%, respectively, and for intracardiac abscesses 28–50% vs. 80–90%, respectively [17][18][19][20]. In patients with prosthetic valve IE, TEE is of particular interest for subaortic complications detection as they are frequently underestimated with TTE [21]. Detection of abscesses or pseudoaneurysms in patients via TEE is also independently associated with increased in-hospital mortality and morbidity [22]. TEE also is the preferred modality to assess paravalvular leaks and has a higher accuracy than TTE for identifying leaflet perforation, prosthetic valve dehiscence, and fistulas. For perforation, the sensitivity and specificity of TEE was reported to be 79% and 93%, respectively [23]. Additionally, the sensitivities and specificities for abscess, fistulas, and dehiscence were 70.3% vs. 95.5%, 85.7% vs. 98.6%, and 66.6% vs. 99.2%, respectively [23]. Furthermore, echocardiography can also predict the embolic risk associated with IE lesions. Although embolic risk is multifactorial, two of the strongest predictors are the size and mobility of the vegetations [24][25][26][27][28]. Neurological emboli are seen most in large vegetations (>3 cm in greatest dimension) [29].

Table 2. Sensitivities and specificities for multi-modality imaging for evaluating various infective endocarditis findings.

| All Cases | PVIE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||

| Vegetations | TTE | 61% [30] | 94% [30] | 29% [31] | 100% [31] |

| TEE [23] | 96% | 83% | 89% | 74% | |

| CCT [23] | 85% | 84% | 78% | 94% | |

| Perivalvular complications | TTE | 28% [20] | 98.6% [20] | 36% [31] | 93% [31] |

| TEE | 70% [23] | 96% [23] | 86% [31] | 98% [31] | |

| CCT [23] | 88% | 93% | |||

| Perforation | TTE | ||||

| TEE [23] | 79% | 93% | |||

| CCT [23] | 48% | 93% | |||

| Dehiscence | TTE | 11% [31] | 100% [31] | ||

| TEE | 67% [23] | 99% [23] | 94% [31] | 97% [31] | |

| CCT [23] | 46% | 97% | |||

| All cases of endocarditis | TTE | 71% [32] | 80% [32] | 33% [31] | 100% [31] |

| TEE | 90% [22] | 96% [22] | 86% [31] | 95% [31] | |

| CCT | ~93% [33] | 95% [33] | |||

| PET [34] | 74% | 88% | 86% | 84% | |

| PET-NVIE | 31% | 98% | |||

| PET-CDRIE | 72% | 83% | |||

Abbreviations: TTE: transthoracic echocardiography, TEE: transesophageal echocardiography, CCT: cardiac computed tomography, PET: 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, NVIE: native valve infective endocarditis, PVIE: prosthetic valve infective valve endocarditis, CDRIE: cardiac device-related infective endocarditis. There are limited data on cardiac magnetic resonance.

2.5. Repeating Echocardiography

In some clinical scenarios, repeat TTE and/or TEE should be considered. In events where both TTE and TEE assessments are negative but clinical suspicion of IE remains high, another TEE should be scheduled. This is especially true when new IE complications arise after initial echocardiographic assessment, such as embolism, heart failure, abscess, a new murmur, atrio-ventricular block, or when there is persistent evidence of sepsis and bacteremia for at least one week despite appropriate antimicrobial treatments [35]. However, no clear consensus exists on the optimal timing of repetition since it greatly depends on the patient’s pathology and risk status. The ACC/AHA 2020 guidelines recommend a TEE repetition 3–5 days after first TEE evaluation, while the ESC guidelines recommend 7–10 days wait before repetition [1][2]. Some studies suggest less of a waiting time before echocardiography repetition in higher risk patients such as those with suspected prosthetic valve IE or Staphylococcus aureus infection [28][36]. This short-term interval repetition should enhance the sensitivity of the assessment [33], although an alternative approach is pursuing other complimentary imaging modalities. Echocardiography should also be repeated at the end of an antimicrobial course to assess for the improvement and resolution of IE findings, and for routine surveillance after valve surgery.

References

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P., 3rd; Gentile, F.; Jneid, H.; Krieger, E.V.; Mack, E.; McLeod, C.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021, 143, e35–e71.

- Habib, G.; Lancellotti, P.; Antunes, M.J.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Casalta, J.P.; Del Zotti, F.; Dulgheru, R.; El Khoury, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3075–3128.

- Li, J.S.; Sexton, D.J.; Mick, N.; Nettles, R.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Ryan, T.; Thomas, B.; Corey, G.R. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, 633–638.

- Iung, B.; Rouzet, F.; Brochet, E.; Duval, X. Cardiac Imaging of Infective Endocarditis, Echo and Beyond. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2017, 19, 8.

- Chambers, H.F.; Bayer, A.S. Native-Valve Infective Endocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 567–576.

- Ashley, E.A.; Niebauer, J. Infective endocarditis. In Cardiology Explained; Remedica: London, UK, 2004.

- Fournier, P.E.; Thuny, F.; Richet, H.; Lepidi, H.; Casalta, J.P.; Arzouni, J.P.; Maurin, M.; Célard, M.; Mainardi, J.-L.; Caus, T.; et al. Comprehensive diagnostic strategy for blood culture-negative endocarditis: A prospective study of 819 new cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 131–140.

- Mitchell, C.; Rahko, P.S.; Blauwet, L.A.; Canaday, B.; Finstuen, J.A.; Foster, M.C.; Horton, K.; Ogunyankin, K.O.; Palma, R.A.; Velazquez, E.J. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2019, 32, 1–64.

- Raoult, D.; Casalta, J.P.; Richet, H.; Khan, M.; Bernit, E.; Rovery, C.; Branger, S.; Gouriet, F.; Imbert, G.; Bothello, E.; et al. Contribution of systematic serological testing in diagnosis of infective endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5238–5242.

- Habib, G.; Badano, L.; Tribouilloy, C.; Vilacosta, I.; Zamorano, J.L.; Galderisi, M.; Voigt, J.-U.; Sicari, R.; Scientific Committee; Cosyns, B.; et al. Recommendations for the practice of echocardiography in infective endocarditis. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2010, 11, 202–219.

- Reynolds, H.R.; Jagen, M.A.; Tunick, P.A.; Kronzon, I. Sensitivity of transthoracic versus transesophageal echocardiography for the detection of native valve vegetations in the modern era. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2003, 16, 67–70.

- Doherty, J.U.; Kort, S.; Mehran, R.; Schoenhagen, P.; Soman, P. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2017 Appropriate Use Criteria for Multimodality Imaging in Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 1647–1672.

- Sordelli, C.; Fele, N.; Mocerino, R.; Weisz, S.H.; Ascione, L.; Caso, P.; Carrozza, A.; Tascini, C.; De Vivo, S.; Severino, S. Infective Endocarditis: Echocardiographic Imaging and New Imaging Modalities. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 2019, 29, 149–155.

- Pérez-García, C.N.; Olmos, C.; Islas, F.; Marcos-Alberca, P.; Pozo, E.; Ferrera, C.; García-Arribas, D.; De Isla, L.P.; Vilacosta, I. Morphological characterization of vegetation by real-time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography in infective endocarditis: Prognostic impact. Echocardiography 2019, 36, 742–751.

- García-Fernández, M.A.; Cortés, M.; García-Robles, J.A.; de Diego, J.J.G.; Perez-David, E.; García, E. Utility of real-time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography in evaluating the success of percutaneous transcatheter closure of mitral paravalvular leaks. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 26–32.

- Berdejo, J.; Shibayama, K.; Harada, K.; Tanaka, J.; Mihara, H.; Gurudevan, S.V.; Siegel, R.J.; Shiota, T. Evaluation of vegetation size and its relationship with embolism in infective endocarditis: A real-time 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 149–154.

- Shapiro, S.M.; Young, E.; De Guzman, S.; Ward, J.; Chiu, C.Y.; Ginzton, L.E.; Bayer, A.S. Transesophageal echocardiography in diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Chest 1994, 105, 377–382.

- Erbel, R.; Rohmann, S.; Drexler, M.; Mohr-Kahaly, S.; Gerharz, C.D.; Iversen, S.; Oelert, H.; Meyer, J. Improved diagnostic value of echocardiography in patients with infective endocarditis by transoesophageal approach. A prospective study. Eur. Heart J. 1988, 9, 43–53.

- Shively, B.K.; Gurule, F.T.; Roldan, C.A.; Leggett, J.H.; Schiller, N.B. Diagnostic value of transesophageal compared with transthoracic echocardiography in infective endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1991, 18, 391–397.

- Daniel, W.G.; Mügge, A.; Martin, R.P.; Lindert, O.; Hausmann, D.; Nonnast-Daniel, B.; Laas, J.; Lichtlen, P.R. Improvement in the diagnosis of abscesses associated with endocarditis by transesophageal echocardiography. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 795–800.

- Karalis, D.G.; Bansal, R.C.; Hauck, A.J.; Ross, J.J., Jr.; Applegate, P.M.; Jutzy, K.R.; Mintz, G.S.; Chandrasekaran, K. Transesophageal echocardiographic recognition of subaortic complications in aortic valve endocarditis. Clinical and surgical implications. Circulation 1992, 86, 353–362.

- Wang, T.K.M.; Bin Saeedan, M.; Chan, N.; Obuchowski, N.A.; Shrestha, N.; Xu, B.; Unai, S.; Cremer, P.; Grimm, R.A.; Griffin, B.P.; et al. Complementary Diagnostic and Prognostic Contributions of Cardiac Computed Tomography for Infective Endocarditis Surgery. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, e011126.

- Jain, V.; Wang, T.K.M.; Bansal, A.; Farwati, M.; Gad, M.; Montane, B.; Kaur, S.; Bolen, M.A.; Grimm, R.; Griffin, B.; et al. Diagnostic performance of cardiac computed tomography versus transesophageal echocardiography in infective endocarditis: A contemporary comparative meta-analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2021, 15, 313–321.

- Vilacosta, I.; Graupner, C.; San Román, J.A.; Sarriá, C.; Ronderos, R.; Fernández, C.; Mancini, L.; Sanz, O.; Sanmartín, L.; Stoermann, W. Risk of embolization after institution of antibiotic therapy for infective endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 1489–1495.

- Steckelberg, J.M.; Murphy, J.G.; Ballard, D.; Bailey, K.; Tajik, A.J.; Taliercio, C.P.; Giuliani, E.R.; Wilson, W.R. Emboli in infective endocarditis: The prognostic value of echocardiography. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991, 114, 635–640.

- Thuny, F.; Di Salvo, G.; Belliard, O.; Avierinos, J.F.; Pergola, V.; Rosenberg, V.; Casalta, J.-P.; Gouvernet, J.; Derumeaux, G.; Iarussi, D.; et al. Risk of embolism and death in infective endocarditis: Prognostic value of echocardiography: A prospective multicenter study. Circulation 2005, 112, 69–75.

- Di Salvo, G.; Habib, G.; Pergola, V.; Avierinos, J.F.; Philip, E.; Casalta, J.P.; Vailloud, J.-M.; Derumeaux, G.; Gouvernet, J.; Ambrosi, P.; et al. Echocardiography predicts embolic events in infective endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 1069–1076.

- Hubert, S.; Thuny, F.; Resseguier, N.; Giorgi, R.; Tribouilloy, C.; Le Dolley, Y.; Casalta, J.-P.; Riberi, A.; Chevalier, F.; Rusinaru, D.; et al. Prediction of symptomatic embolism in infective endocarditis: Construction and validation of a risk calculator in a multicenter cohort. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 1384–1392.

- García-Cabrera, E.; Fernández-Hidalgo, N.; Almirante, B.; Ivanova-Georgieva, R.; Noureddine, M.; Plata, A.; Lomas, J.M.; Gálvez-Acebal, J.; Hidalgo-Tenorio, C.; Ruíz-Morales, J.; et al. Neurological complications of infective endocarditis: Risk factors, outcome, and impact of cardiac surgery: A multicenter observational study. Circulation 2013, 127, 2272–2284.

- Bai, A.D.; Steinberg, M.; Showler, A.; Burry, L.; Bhatia, R.S.; Tomlinson, G.A.; Bell, C.M.; Morris, A.M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Transthoracic Echocardiography for Infective Endocarditis Findings Using Transesophageal Echocardiography as the Reference Standard: A Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 639–646.e8.

- Habets, J.; Tanis, W.; Reitsma, J.B.; van den Brink, R.B.; Mali, W.P.; Chamuleau, S.A.J.; Budde, R.P.J. Are novel non-invasive imaging techniques needed in patients with suspected prosthetic heart valve endocarditis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 2125–2133.

- Bonzi, M.; Cernuschi, G.; Solbiati, M.; Giusti, G.; Montano, N.; Ceriani, E. Diagnostic accuracy of transthoracic echocardiography to identify native valve infective endocarditis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2018, 13, 937–946.

- Lo Presti, S.; Elajami, T.K.; Zmaili, M.; Reyaldeen, R.; Xu, B. Multimodality imaging in the diagnosis and management of prosthetic valve endocarditis: A contemporary narrative review. World J. Cardiol. 2021, 13, 254–270.

- Wang, T.K.M.; Sánchez-Nadales, A.; Igbinomwanhia, E.; Cremer, P.; Griffin, B.; Xu, B. Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis by Subtype Using 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography: A Contemporary Meta-Analysis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, e010600.

- Baddour, L.M.; Wilson, W.R.; Bayer, A.S.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Tleyjeh, I.M.; Rybak, M.J.; Barsic, B.; Lockhart, P.B.; Gewitz, M.H.; Levison, M.E.; et al. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 132, 1435–1486.

- Eudailey, K.; Lewey, J.; Hahn, R.T.; George, I. Aggressive infective endocarditis and the importance of early repeat echocardiographic imaging. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 147, e26–e28.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cardiac & Cardiovascular Systems

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

894

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

03 Mar 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No