You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rachel Occhiogrosso Abelman | -- | 1402 | 2023-02-27 18:58:32 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1402 | 2023-02-28 02:38:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Abelman, R.O.; Wu, B.; Spring, L.M.; Ellisen, L.W.; Bardia, A. Antibody–Drug Conjugates Approved in Breast Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41715 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

Abelman RO, Wu B, Spring LM, Ellisen LW, Bardia A. Antibody–Drug Conjugates Approved in Breast Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41715. Accessed December 22, 2025.

Abelman, Rachel Occhiogrosso, Bogang Wu, Laura M. Spring, Leif W. Ellisen, Aditya Bardia. "Antibody–Drug Conjugates Approved in Breast Cancer" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41715 (accessed December 22, 2025).

Abelman, R.O., Wu, B., Spring, L.M., Ellisen, L.W., & Bardia, A. (2023, February 27). Antibody–Drug Conjugates Approved in Breast Cancer. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41715

Abelman, Rachel Occhiogrosso, et al. "Antibody–Drug Conjugates Approved in Breast Cancer." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 February, 2023.

Copy Citation

Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), with antibodies targeted against specific antigens linked to cytotoxic payloads, offer the opportunity for a more specific delivery of chemotherapy and other bioactive payloads to minimize side effects. First approved in the setting of HER2+ breast cancer, more recent ADCs have been developed for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancer.

antibody–drug conjugates

breast cancer

targeted therapies

1. Introduction

Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), novel agents that use selective targeting by monoclonal antibodies to deliver cytotoxic chemotherapies and other bioactive payloads to cells expressing a particular antigen, seek to deliver highly potent agents while minimizing off-target toxicity. In recent years, successful trials of ADCs in breast cancer and other malignancies have demonstrated that ADCs can be effective and limit toxicity, in some cases supplanting traditional chemotherapy. While these agents have had marked success, particularly in the metastatic setting, almost all advance-stage patients treated with ADCs develop resistance. Efforts to characterize and define the mechanisms to explain resistance have incorporated both pre-clinical models and clinical investigation, spanning genomics to proteomics and even direct visualization of resistant cell lines. Altogether, recent discoveries of the processes mediating resistance provide hope for new innovations that expand the therapeutic window of these highly active therapies.

2. Mechanism of Action

ADCs are composed of an antibody targeting an antigen associated with malignancy, combined through a linker with a cytotoxic moiety, allowing for a more specific delivery of chemotherapy. The ADC binds a receptor on the target cell and is then internalized into the cell through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Once inside the cell, the antibody and cytotoxic agent are separated in the lysosome, where the linker is cleaved, releasing the payload. Targeting cells via antibodies aims at specifically delivering the payload while minimizing toxicity, enabling the use of chemotherapy as much as 100 to 1000 times more concentrated than standard cytotoxic chemotherapy [1].

The antibody selected for use in ADCs is often immunoglobulin G (IgG), most often the IgG1 subclass. Antigen targets are ideally ubiquitous in malignant cells but are rarely found in normal cells, to limit off-target toxicity [2]. Antibodies are connected to payloads through novel linkers that vary in properties, in ways that can be manipulated for therapeutic use. Linkers can be non-cleavable, requiring additional processing to release their payload, or cleavable, in the event of tumor-specific factors such as a change in pH or enzyme. Cleavable linkers provide the advantage of a more efficient delivery of the chemotherapy payload and may be more likely to impact neighboring antigen-negative cells, which may or may not be desirable. In contrast, non-cleavable linkers may deliver their payload with more specificity but may also need additional processing such as lysosomal degradation, which can impact the payload [3]. The chemotherapy agents used are typically more potent than can be tolerated in a conventional delivery. Agents of choice include auristatins, calicheamicins, maytansinoids, and camptothecin analogues [2].

ADCs can also be categorized by their drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR), a measure of the number of chemotherapy moieties conjugated to each antibody. In theory, ADCs with a higher DAR would be expected to be more potent, although in some situations drugs with higher DARs were found to have an increased hepatic clearance that may limit their efficacy [4][5]. ADCs were first demonstrated to have efficacy in settings where cancer was relapsed or refractory to standard chemotherapy treatments. The success in ADCs vs. standard therapy in these cases may be related to the increased heterogeneity in pretreated tumors. This efficacy may be mediated by the “bystander effect”, where tissues adjacent to those expressing the target antigen are also targeted by the cytotoxic payload [6][7]. This effect was observed in early studies of the ADC trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd), where HER2- cells’ neighboring cells that were expressing HER2 were also targeted by the agent [1][6]. While this mechanism provides impact in heterogeneous tumors, given decreased specificity there is an increased risk of toxicity [2].

3. ADCs Approved in Breast Cancer

Trastuzumab emtansine, known as T-DM1, was the first antibody–drug conjugate approved for use in breast cancer. In the TH3RESA trial, T-DM1 demonstrated an improved PFS (6.2 months vs. 3.3 months, HR 0.528) and later overall survival compared to the treatment of physician’s choice for patients with HER2+ breast cancer who had already previously received two prior lines of chemotherapy including a taxane in any setting and trastuzumab/lapatinib for an advanced disease [8]. Notably, T-DM1 retained activity against tumors that had progressed on prior HER2-directed therapy, an early indication that antibody–drug conjugates may have renewed efficacy against previously exploited targets. In the EMILIA study, HER2+ metastatic breast cancer previously treated with trastuzumab and a taxane demonstrated an improved PFS (9.6 vs. 6.4 months, HR 0.68) compared to lapatinib/capecitabine and also demonstrated an improved overall survival (30.9 months vs. 25.1 months, HR 0.68, p < 0.001). This result elevated T-DM1 to a second-line therapy for metastatic HER2+ disease [9]. While early studies demonstrated promise, there were some limitations to the success of the agent, as seen in the MARIANNE study, where T-DM1 with and without pertuzumab was not superior to the combination of trastuzumab and a taxane as the first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer [10]. In the KRISTINE trial, T-DM1 and pertuzumab (P) were less effective in leading to a pathologic complete response (pCR) than TCHP for neoadjuvant use in early-stage/local HER2+ breast cancer [11]. Notably, 44% in the T-DM1+P arm still achieved pCR without the use of cytotoxic chemotherapy, suggesting some role for this type of de-escalation in the future. Patients who had a progression prior to surgery were more likely to have heterogeneous HER2 expression, suggesting that patients with a high/more homogenous HER2 staining could be selected for targeted de-escalation in a different setting [12]. Finally, the KATHERINE trial demonstrated the effective use of T-DM1 for patients with residual HER2+ disease after neoadjuvant use of trastuzumab and a taxane, with invasive disease found in 12.2% of the cohort that had received 14 cycles of T-DM1 after surgery, compared to 22.2% of the group that received trastuzumab after surgery [13].

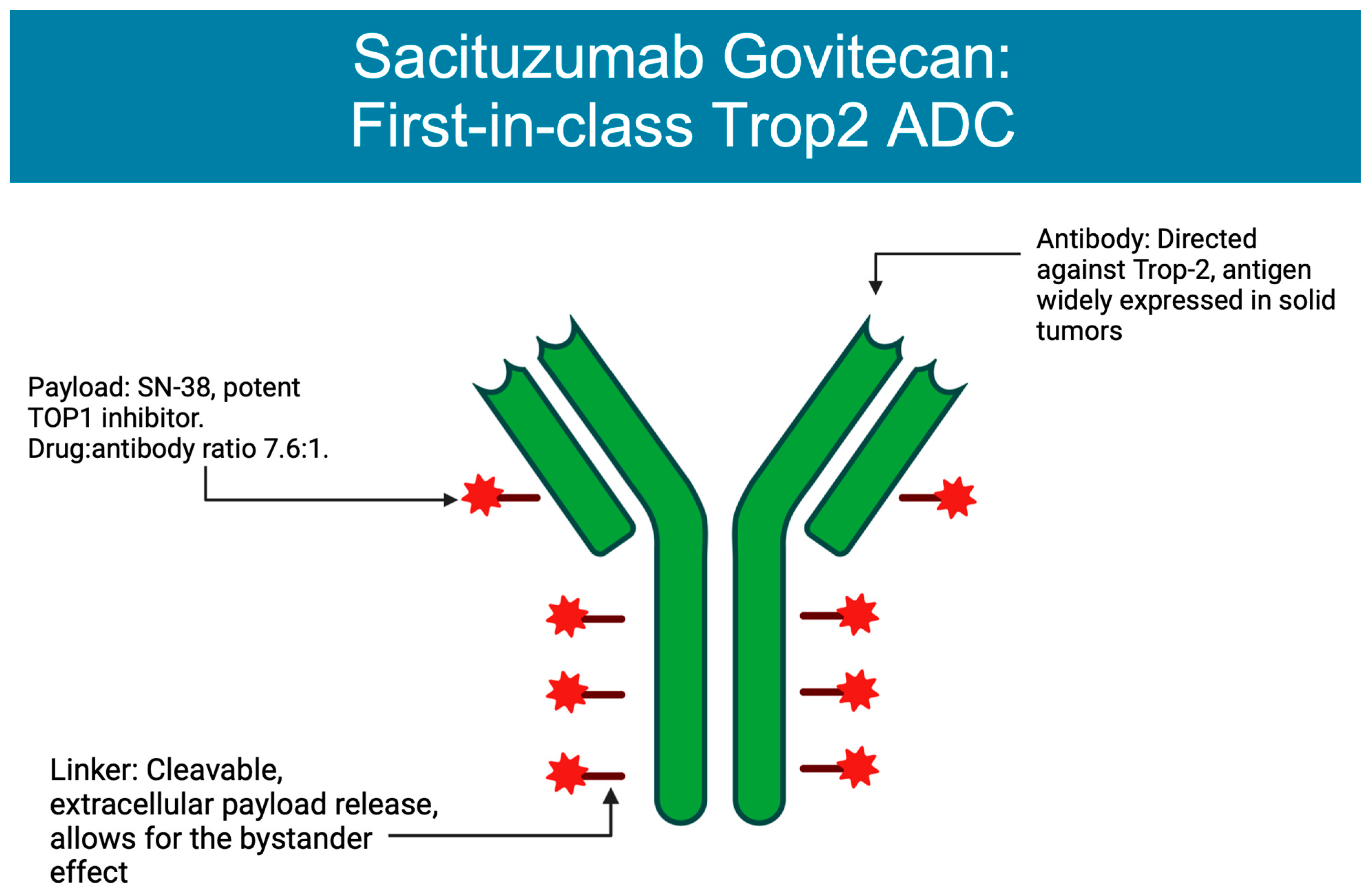

The next antibody–drug conjugate approved for use in breast cancer was sacituzumab govitecan (SG), composed of a monoclonal antibody targeting TROP-2 that is connected via a cleavable linker to SN-38, an irinotecan metabolite [14] (Figure 1). SG obtained approval based on the ASCENT trial, a phase III trial comparing SG vs. single agent chemotherapy in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who had received two prior lines of chemotherapy. Patients treated with SG were found to have an improved PFS of 5.6 months compared to 1.7 months for those receiving the treatment of physician’s choice, along with an improved median overall survival of 12.1 months vs. 6.7 months in the TPC (treatment of physician’s choice) group [15]. As a result of these data, SG received full FDA approval for treatment of mTNBC as a second-line treatment, the first approved ADC for metastatic mTNBC [16], and in 2023 also received approval for patients with metastatic Hormone Receptor Breast cancer.

Figure 1. Structure of sacituzumab govitecan. Figure created on BioRender.

Finally, trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) was most recently the second antibody–drug conjugate approved for use in HER2+ advanced breast cancer and has also defined a new class of “HER2-low” disease. T-DXd is composed of trastuzumab combined via a cleavable linker with deruxtecan, a topoisomerase-I inhibitor. This compound has a relatively high drug:antibody ratio of 8:1, a property along with the linker structure that may explain its efficacy in patients with heterogeneous HER2 expression [17][18][19]. T-DXd was studied in a series of trials known as the DESTINY-Breast trials, with many still ongoing. In DESTINY-Breast 01, T-DXd demonstrated a confirmed response of 60.9% in patients with metastatic HER2+ breast cancer previously treated with T-DM1, with a median progression-free survival of 16.4 months [20]. T-DXd was compared directly to T-DM1 in DESTINY-Breast 03, demonstrating an overall response rate of 79.7% in the T-DXd group vs. 34.2% in the T-DM1 group, with a median PFS that was unable to be calculated due to ongoing treatment in the T-DXd group, compared to 6.8 months in the T-DM1 group [21]. As noted above, T-DXd demonstrated efficacy in clinically HER2-negative patients with heterogeneous HER2 expression, effectively creating a new clinical categorization of patients with HER2-low disease (IHC 1+ or IHC 2+ without FISH amplification). In the DESTINY-Breast 04 trial, patients classified as HER2-low who, like above, had metastatic disease and had previously received 1–2 lines of therapy demonstrated an improved response to T-DXd compared to TPC, with a median PFS of 9.9 months vs. 5.1 months in TPC, and OS of 23.4 months in the T-DXd group vs. 16.8 months in the TPC cohort [22].

References

- Nagayama, A.; Ellisen, L.W.; Chabner, B.; Bardia, A. Antibody–Drug Conjugates for the Treatment of Solid Tumors: Clinical Experience and Latest Developments. Target. Oncol. 2017, 12, 719–739.

- Drago, J.Z.; Modi, S.; Chandarlapaty, S. Unlocking the potential of antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 327–344.

- Jain, N.; Smith, S.W.; Ghone, S.; Tomczuk, B. Current ADC Linker Chemistry. Pharm. Res. 2015, 32, 3526–3540.

- Hamblett, K.J.; Senter, P.D.; Chace, D.F.; Sun, M.M.C.; Lenox, J.; Cerveny, C.G.; Kissler, K.M.; Bernhardt, S.X.; Kopcha, A.K.; Zabinski, R.F.; et al. Effects of drug loading on the antitumor activity of a monoclonal antibody drug conjugate. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 7063–7070.

- Sun, X.; Ponte, J.F.; Yoder, N.C.; Laleau, R.; Coccia, J.; Lanieri, L.; Qiu, Q.; Wu, R.; Hong, E.; Bogalhas, M.; et al. Effects of Drug–Antibody Ratio on Pharmacokinetics, Biodistribution, Efficacy, and Tolerability of Antibody–Maytansinoid Conjugates. Bioconjug. Chem. 2017, 28, 1371–1381.

- Ogitani, Y.; Hagihara, K.; Oitate, M.; Naito, H.; Agatsuma, T. Bystander killing effect of DS-8201a, a novel anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 antibody-drug conjugate, in tumors with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterogeneity. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 1039–1046.

- Modi, S.; Park, H.; Murthy, R.K.; Iwata, H.; Tamura, K.; Tsurutani, J.; Moreno-Aspitia, A.; Doi, T.; Sagara, Y.; Redfern, C.; et al. Antitumor Activity and Safety of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients With HER2-Low-Expressing Advanced Breast Cancer: Results From a Phase Ib Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1887–1896.

- Krop, I.E.; Kim, S.B.; González-Martín, A.; LoRusso, P.M.; Ferrero, J.M.; Smitt, M.; Yu, R.; Leung, A.C.; Wildiers, H. Trastuzumab emtansine versus treatment of physician’s choice for pretreated HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (TH3RESA): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 689–699.

- Verma, S.; Miles, D.; Gianni, L.; Krop, I.E.; Welslau, M.; Baselga, J.; Pegram, M.; Oh, D.-Y.; Diéras, V.; Guardino, E.; et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1783–1791.

- Perez, E.A.; Barrios, C.; Eiermann, W.; Toi, M.; Im, Y.H.; Conte, P.; Martin, M.; Pienkowski, T.; Pivot, X.; Burris, H., 3rd; et al. Trastuzumab Emtansine With or Without Pertuzumab Versus Trastuzumab Plus Taxane for Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive, Advanced Breast Cancer: Primary Results From the Phase III MARIANNE Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 141–148.

- Hurvitz, S.A.; Martin, M.; Symmans, W.F.; Jung, K.H.; Huang, C.-S.; Thompson, A.M.; Harbeck, N.; Valero, V.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Wildiers, H.; et al. Neoadjuvant trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and chemotherapy versus trastuzumab emtansine plus pertuzumab in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (KRISTINE): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 115–126.

- Hunter, F.W.; Barker, H.R.; Lipert, B.; Rothé, F.; Gebhart, G.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.J.; Sotiriou, C.; Jamieson, S.M.F. Mechanisms of resistance to trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in HER2-positive breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 603–612.

- von Minckwitz, G.; Huang, C.S.; Mano, M.S.; Loibl, S.; Mamounas, E.P.; Untch, M.; Wolmark, N.; Rastogi, P.; Schneeweiss, A.; Redondo, A.; et al. Trastuzumab Emtansine for Residual Invasive HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 617–628.

- Bardia, A.; Mayer, I.A.; Vahdat, L.T.; Tolaney, S.M.; Isakoff, S.J.; Diamond, J.R.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Moroose, R.L.; Santin, A.D.; Abramson, V.G.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy in Refractory Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 741–751.

- Bardia, A.; Tolaney, S.M.; Loirat, D.; Punie, K.; Oliveira, M.; Rugo, H.S.; Brufsky, A.; Kalinsky, K.; Cortes, J.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; et al. Sacituzumab govitecan (SG) versus treatment of physician’s choice (TPC) in patients (pts) with previously treated, metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC): Final results from the phase 3 ASCENT study. J. Clin. Orthod. 2022, 40, 1071.

- Bardia, A.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Tolaney, S.M.; Loirat, D.; Punie, K.; Oliveira, M.; Brufsky, A.; Sardesai, S.D.; Kalinsky, K.; Zelnak, A.B.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1529–1541.

- García-Alonso, S.; Ocaña, A.; Pandiella, A. Resistance to Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 2159–2165.

- Ocaña, A.; Amir, E.; Pandiella, A. HER2 heterogeneity and resistance to anti-HER2 antibody-drug conjugates. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 15.

- Ferraro, E.; Drago, J.Z.; Modi, S. Implementing antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) in HER2-positive breast cancer: State of the art and future directions. Breast Cancer Res. 2021, 23, 84.

- Modi, S.; Saura, C.; Yamashita, T.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, S.-B.; Tamura, K.; Andre, F.; Iwata, H.; Ito, Y.; Tsurutani, J.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 610–621.

- Cortés, J.; Kim, S.-B.; Chung, W.-P.; Im, S.-A.; Park, Y.H.; Hegg, R.; Kim, M.H.; Tseng, L.-M.; Petry, V.; Chung, C.-F.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan versus Trastuzumab Emtansine for Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1143–1154.

- Modi, S.; Jacot, W.; Yamashita, T.; Sohn, J.; Vidal, M.; Tokunaga, E.; Tsurutani, J.; Ueno, N.T.; Prat, A.; Chae, Y.S.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Low Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 9–20.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.5K

Entry Collection:

Biopharmaceuticals Technology

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Feb 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No