| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andreea Ioana Inceu | -- | 7896 | 2023-02-21 14:16:54 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 7896 | 2023-02-22 01:58:00 | | |

Video Upload Options

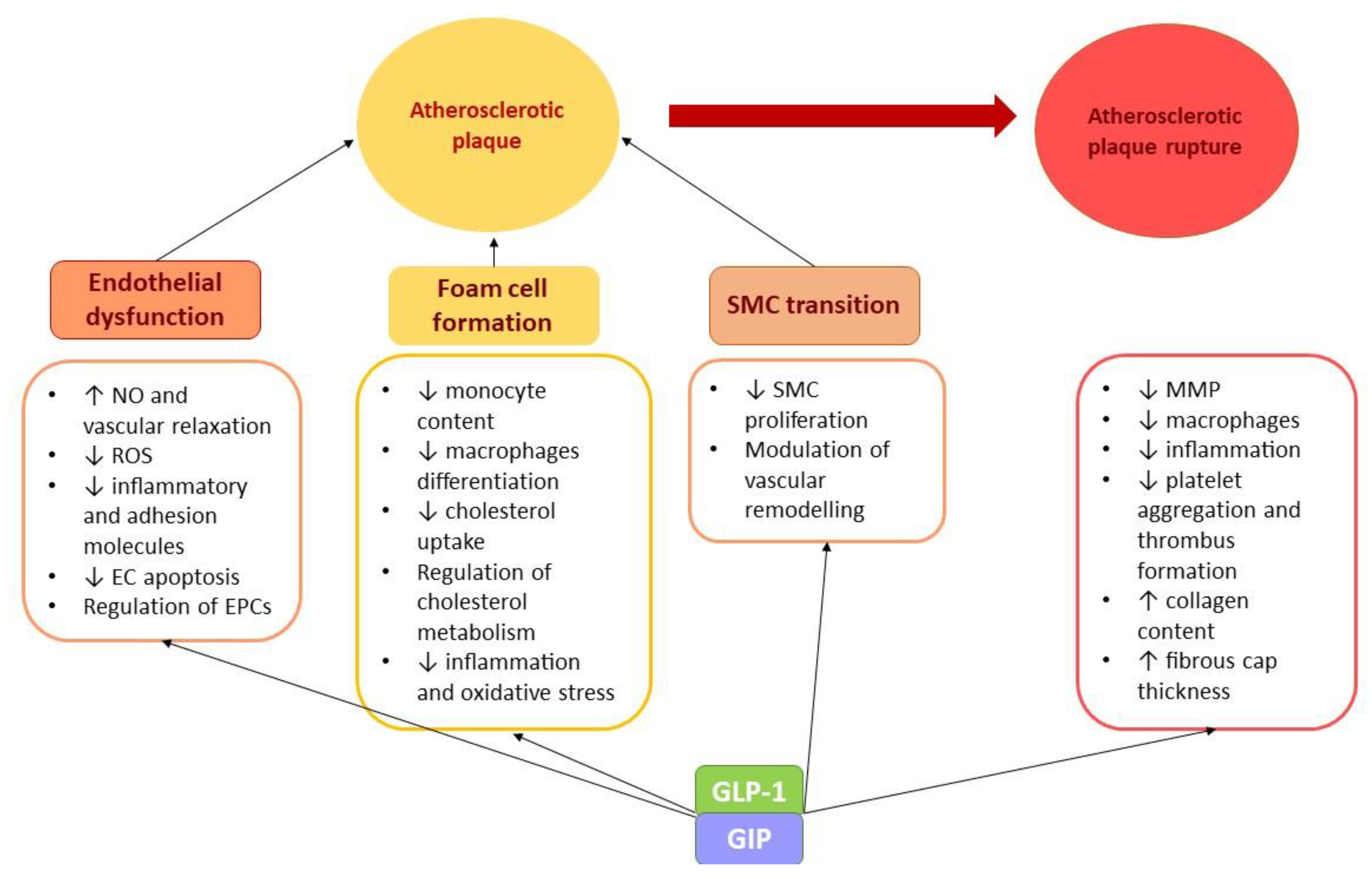

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Diabetes mellitus increases cardiovascular risk. Heart failure and atrial fibrillation are associated comorbidities that share the main cardiovascular risk factors. The use of incretin-based therapies promoted the idea that activation of alternative signaling pathways is effective in reducing the risk of atherosclerosis and heart failure. Gut-derived molecules, gut hormones, and gut microbiota metabolites showed both positive and detrimental effects in cardiometabolic disorders. Although inflammation plays a key role in cardiometabolic disorders, additional intracellular signaling pathways are involved and could explain the observed effects.

1. Atherosclerosis

1.1. Gut Peptides

-

GLP-1. GIP

-

Ghrelin

1.2. Gut Microbiota

-

TMAO

-

LPS

2. Heart Failure

2.1. Gut Peptides

-

GLP-1. GIP

-

Ghrelin

-

CCK

2.2. Gut Microbiota-Derived Products

-

TMAO

-

LPS

3. Atrial Fibrillation

References

- Björkegren, J.L.M.; Lusis, A.J. Atherosclerosis: Recent developments. Cell 2022, 185, 1630–1645.

- Jonik, S.; Marchel, M.; Grabowski, M.; Opolski, G.; Mazurek, T. Gastrointestinal Incretins—Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) and Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) beyond Pleiotropic Physiological Effects Are Involved in Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis and Coronary Artery Disease—State of the Art. Biology 2022, 11, 288.

- Oyama, J.-i.; Higashi, Y.; Node, K. Do incretins improve endothelial function? Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 1–8.

- Lim, D.M.; Park, K.Y.; Hwang, W.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, B.J. Difference in protective effects of GIP and GLP-1 on endothelial cells according to cyclic adenosine monophosphate response. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 2558–2564.

- Cai, X.; She, M.; Xu, M.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Zheng, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; et al. GLP-1 treatment protects endothelial cells from oxidative stress-induced autophagy and endothelial dysfunction. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1696–1708.

- Wang, D.; Luo, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Sun, D.; Zhang, R.; Su, T.; Ma, X.; Zeng, C.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 protects against cardiac microvascular injury in diabetes via a cAMP/PKA/Rho-dependent mechanism. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1697–1708.

- Xie, X.Y.; Mo, Z.H.; Chen, K.; He, H.H.; Xie, Y.H. Glucagon-like peptide-1 improves proliferation and differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells via upregulating VEGF generation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011, 17, 35–41.

- Garczorz, W.; Gallego-Colon, E.; Kosowska, A.; Kłych-Ratuszny, A.; Woźniak, M.; Marcol, W.; Niesner, K.; Francuz, T. Exenatide exhibits anti-inflammatory properties and modulates endothelial response to Tumor Necrosis Factor α-mediated activation. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2017, 36, e12317.

- Torres, G.; Morales, P.E.; García-Miguel, M.; Norambuena-Soto, I.; Cartes-Saavedra, B.; Vidal-Peña, G.; Moncada-Ruff, D.; Sanhueza-Olivares, F.; San Martín, A.; Chiong, M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell dedifferentiation through mitochondrial dynamics regulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 104, 52–61.

- Gallego-Colon, E.; Klych-Ratuszny, A.; Kosowska, A.; Garczorz, W.; Mohammad, M.R.; Wozniak, M.; Francuz, T. Exenatide modulates metalloproteinase expression in human cardiac smooth muscle cells via the inhibition of Akt signaling pathway. Pharmacol. Rep. 2018, 70, 178–183.

- Nogi, Y.; Nagashima, M.; Terasaki, M.; Nohtomi, K.; Watanabe, T.; Hirano, T. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide prevents the progression of macrophage-driven atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-null mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 1–8.

- Terasaki, M.; Yashima, H.; Mori, Y.; Saito, T.; Shiraga, Y.; Kawakami, R.; Ohara, M.; Fukui, T.; Hirano, T.; Yamada, Y.; et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide suppresses foam cell formation of macrophages through inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase 5-cd36 pathway. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 832.

- Kahles, F.; Liberman, A.; Halim, C.; Rau, M.; Möllmann, J.; Mertens, R.W.; Rückbeil, M.; Diepolder, I.; Walla, B.; Diebold, S.; et al. The incretin hormone GIP is upregulated in patients with atherosclerosis and stabilizes plaques in ApoE−/− mice by blocking monocyte/macrophage activation. Mol. Metab. 2018, 14, 150–157.

- Terasaki, M.; Nagashima, M.; Nohtomi, K.; Kohashi, K.; Tomoyasu, M.; Sinmura, K.; Nogi, Y.; Katayama, Y.; Sato, K.; Itoh, F.; et al. Preventive Effect of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor on Atherosclerosis Is Mainly Attributable to Incretin’s Actions in Nondiabetic and Diabetic Apolipoprotein E-Null Mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 1–12.

- Wiciński, M.; Górski, K.; Wódkiewicz, E.; Walczak, M.; Nowaczewska, M.; Malinowski, B. Vasculoprotective effects of vildagliptin. Focus on atherogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2275.

- Ceriello, A.; Esposito, K.; Testa, R.; Bonfigli, A.R.; Marra, M.; Giugliano, D. The possible protective role of glucagon-like peptide1 on endothelium during the meal and evidence for an “endothelial resistance” to glucagon-like peptide 1 in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 697–702.

- Bunck, M.C.; Cornér, A.; Eliasson, B.; Heine, R.J.; Shaginian, R.M.; Wu, Y.; Yan, P.; Smith, U.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Diamant, M.; et al. One-year treatment with exenatide vs. Insulin Glargine: Effects on postprandial glycemia, lipid profiles, and oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis 2010, 212, 223–229.

- Zhang, J.; Xian, T.Z.; Wu, M.X.; Li, C.; Pan, Q.; Guo, L.X. Comparison of the effects of twice-daily exenatide and insulin on carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A 52-week randomized, open-label, controlled trial. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 1–9.

- Marsico, F.; Paolillo, S.; Gargiulo, P.; Bruzzese, D.; Dell’Aversana, S.; Esposito, I.; Renga, F.; Esposito, L.; Marciano, C.; Dellegrottaglie, S.; et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on major cardiovascular events in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus with or without established cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3346–3358.

- Cameron-Vendrig, A.; Reheman, A.; Siraj, M.A.; Xu, X.R.; Wang, Y.; Lei, X.; Afroze, T.; Shikatani, E.; El-Mounayri, O.; Noyan, H.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor activation attenuates platelet aggregation and thrombosis. Diabetes 2016, 65, 1714–1723.

- Sternkopf, M.; Nagy, M.; Baaten, C.C.F.M.J.; Kuijpers, M.J.E.; Tullemans, B.M.E.; Wirth, J.; Theelen, W.; Mastenbroek, T.G.; Lehrke, M.; Winnerling, B.; et al. Native, intact glucagon-like peptide 1 is a natural suppressor of thrombus growth under physiological flow conditions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, E65–E77.

- Laurila, M.; Santaniemi, M.; Kesäniemi, Y.A.; Ukkola, O. High plasma ghrelin protects from coronary heart disease and Leu72Leu polymorphism of ghrelin gene from cancer in healthy adults during the 19 years follow-up study. Peptides 2014, 61, 122–129.

- Zanetti, M.; Gortan Cappellari, G.; Semolic, A.; Burekovic, I.; Fonda, M.; Cattin, L.; Barazzoni, R. Gender-Specific Association of Desacylated Ghrelin with Subclinical Atherosclerosis in the Metabolic Syndrome. Arch. Med. Res. 2017, 48, 441–448.

- Ai, W.; Wu, M.; Chen, L.; Jiang, B.; Mu, M.; Liu, L.; Yuan, Z. Ghrelin ameliorates atherosclerosis by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 31, 147–154.

- Iantorno, M.; Chen, H.; Kim, J.A.; Tesauro, M.; Lauro, D.; Cardillo, C.; Quon, M.J. Ghrelin has novel vascular actions that mimic PI 3-kinase-dependent actions of insulin to stimulate production of NO from endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 292, 756–764.

- Tesauro, M.; Schinzari, F.; Iantorno, M.; Rizza, S.; Melina, D.; Lauro, D.; Cardillo, C. Ghrelin improves endothelial function in patients with metabolic syndrome. Circulation 2005, 112, 2986–2992.

- Ruolan, Z. Ghrelin suppresses inflammation in HUVECs by inhibiting ubiquitin-mediated uncoupling protein 2 degradation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 39, 1421–1427.

- Xu, M.; Liu, L.; Song, C.; Chen, W.; Gui, S. Ghrelin improves vascular autophagy in rats with vascular calcification. Life Sci. 2017, 179, 23–29.

- Togliatto, G.; Trombetta, A.; Dentelli, P.; Gallo, S.; Rosso, A.; Cotogni, P.; Granata, R.; Falcioni, R.; Delale, T.; Ghigo, E.; et al. Unacylated ghrelin induces oxidative stress resistance in a glucose intolerance and peripheral artery disease mouse model by restoring endothelial cell MIR-126 expression. Diabetes 2015, 64, 1370–1382.

- Zanetti, M.; Cappellari, G.G.; Graziani, A.; Barazzoni, R. Unacylated ghrelin improves vascular dysfunction and attenuates atherosclerosis during high-fat diet consumption in rodents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 499.

- Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Ke, D.; Li, G. Ghrelin inhibits atherosclerotic plaque angiogenesis and promotes plaque stability in a rabbit atherosclerotic model. Peptides 2017, 90, 17–26.

- Zhang, M.; Qu, X.; Yuan, F.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Dai, J.; Wang, W.; Fei, J.; Hou, X.; Fang, W. Ghrelin receptor deficiency aggravates atherosclerotic plaque instability. Front. Biosci. -Landmark 2015, 20, 604–613.

- Shu, Z.W.; Yu, M.; Chen, X.J.; Tan, X.R. Ghrelin could be a candidate for the prevention of in-stent restenosis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2013, 27, 309–314.

- Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Li, G.; Ke, D. Ghrelin ameliorates impaired angiogenesis of ischemic myocardium through GHSR1a-mediated AMPK/eNOS signal pathway in diabetic rats. Peptides 2015, 73, 77–87.

- Katare, R.; Rawal, S.; Munasinghe, P.E.; Tsuchimochi, H.; Inagaki, T.; Fujii, Y.; Dixit, P.; Umetani, K.; Kangawa, K.; Shirai, M.; et al. Ghrelin promotes functional angiogenesis in a mouse model of critical limb ischemia through activation of proangiogenic MicroRNAs. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 432–445.

- Wang, B.; Qiu, J.; Lian, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, J. Gut Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide in Atherosclerosis: From Mechanism to Therapy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 1560.

- Tang, W.H.W.; Li, X.S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Khaw, T.; Wareham, N.J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Boekholdt, M.; Hazen, S.L. Plasma trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) levels predict future risk of coronary artery disease in apparently healthy individuals in the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. Am. Heart J. 2021, 236, 80–86.

- Randrianarisoa, E.; Lehn-Stefan, A.; Wang, X.; Hoene, M.; Peter, A.; Heinzmann, S.S.; Zhao, X.; Königsrainer, I.; Königsrainer, A.; Balletshofer, B.; et al. Relationship of serum trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) levels with early atherosclerosis in humans. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–9.

- Bogiatzi, C.; Gloor, G.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Reid, G.; Wong, R.G.; Urquhart, B.L.; Dinculescu, V.; Ruetz, K.N.; Velenosi, T.J.; Pignanelli, M.; et al. Metabolic products of the intestinal microbiome and extremes of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2018, 273, 91–97.

- Roncal, C.; Martínez-Aguilar, E.; Orbe, J.; Ravassa, S.; Fernandez-Montero, A.; Saenz-Pipaon, G.; Ugarte, A.; Estella-Hermoso de Mendoza, A.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Fernández-Alonso, S.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO) Predicts Cardiovascular Mortality in Peripheral Artery Disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–8.

- Heianza, Y.; Ma, W.; Manson, J.A.E.; Rexrode, K.M.; Qi, L. Gut microbiota metabolites and risk of major adverse cardiovascular disease events and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004947.

- Koeth, R.A.; Levison, B.S.; Culley, M.K.; Buffa, J.A.; Wang, Z.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Smith, J.D.; et al. γ-butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L-carnitine to TMAO. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 799–812.

- Skagen, K.; Trøseid, M.; Ueland, T.; Holm, S.; Abbas, A.; Gregersen, I.; Kummen, M.; Bjerkeli, V.; Reier-Nilsen, F.; Russell, D.; et al. The Carnitine-butyrobetaine-trimethylamine-N-oxide pathway and its association with cardiovascular mortality in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2016, 247, 64–69.

- Bir Singh, G.; Zhang, Y.; Boini, K.M.; Koka, S. High Mobility Group Box 1 Mediates TMAO-Induced endothelial dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3570.

- Wu, P.; Chen, J.N.; Chen, J.J.; Tao, J.; Wu, S.Y.; Xu, G.S.; Wang, Z.; Wei, D.H.; Yin, W.D. Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes apoE−/− mice atherosclerosis by inducing vascular endothelial cell pyroptosis via the SDHB/ROS pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 6582–6591.

- Ma, G.H.; Pan, B.; Chen, Y.; Guo, C.X.; Zhao, M.M.; Zheng, L.M.; Chen, B.X. Trimethylamine N-oxide in atherogenesis: Impairing endothelial self-repair capacity and enhancing monocyte adhesion. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37, 1–12.

- Sun, X.; Jiao, X.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Chen, Y. Trimethylamine N-oxide induces inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in human umbilical vein endothelial cells via activating ROS-TXNIP-NLRP3 inflammasome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 481, 63–70.

- Chou, R.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, I.C.; Huang, H.L.; Lu, Y.W.; Kuo, C.S.; Chang, C.C.; Huang, P.H.; Chen, J.W.; Lin, S.J. Trimethylamine N-Oxide, Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells, and Endothelial Function in Patients with Stable Angina. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10.

- Zhou, S.; Xue, J.; Shan, J.; Hong, Y.; Zhu, W.; Nie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, N.; Luo, X.; Zhang, T.; et al. Gut-Flora-Dependent Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Promotes Atherosclerosis-Associated Inflammation Responses by Indirect ROS Stimulation and Signaling Involving AMPK and SIRT1. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3338.

- Liu, H.; Jia, K.; Ren, Z.; Sun, J.; Pan, L.L. PRMT5 critically mediates TMAO-induced inflammatory response in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1–11.

- Seldin, M.M.; Meng, Y.; Qi, H.; Zhu, W.F.; Wang, Z.; Hazen, S.L.; Lusis, A.J.; Shih, D.M. Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes vascular inflammation through signaling of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κb. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002767.

- Chen, M.L.; Zhu, X.H.; Ran, L.; Lang, H.D.; Yi, L.; Mi, M.T. Trimethylamine-N-oxide induces vascular inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through the SIRT3-SOD2-mtROS signaling pathway. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006347.

- Ding, L.; Chang, M.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xue, C.; Yanagita, T.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y. Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)-induced atherosclerosis is associated with bile acid metabolism. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 1–8.

- Geng, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Hu, T.; Gu, Y.; Li, J. Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes atherosclerosis via CD36-dependent MAPK/JNK pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 941–947.

- Mohammadi, A.; Najar, A.G.; Yaghoobi, M.M.; Jahani, Y.; Vahabzadeh, Z. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Treatment Induces Changes in the ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter A1 and Scavenger Receptor A1 in Murine Macrophage J774A.1 cells. Inflammation 2016, 39, 393–404.

- Mondal, J.A. Effect of Trimethylamine N-Oxide on Interfacial Electrostatics at Phospholipid Monolayer-Water Interfaces and Its Relevance to Cardiovascular Disease. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 1704–1708.

- Luo, T.; Liu, D.; Guo, Z.; Chen, P.; Guo, Z.; Ou, C.; Chen, M. Deficiency of proline/serine-rich coiled-coil protein 1 (PSRC1) accelerates trimethylamine N-oxide-induced atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2022, 170, 60–74.

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, P.; Liu, X.; Lu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Ou, C.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide promotes vascular calcification through activation of NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, pyrin domain-containing-3) inflammasome and NF-κB (nuclear factor κb) signals. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 3, 751–765.

- Koay, Y.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Wali, J.A.; Luk, A.W.S.; Li, M.; Doma, H.; Reimark, R.; Zaldivia, M.T.K.; Habtom, H.T.; Franks, A.E.; et al. Plasma levels of trimethylamine-N-oxide can be increased with “healthy” and “unhealthy” diets and do not correlate with the extent of atherosclerosis but with plaque instability. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 435–449.

- Shi, W.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yu, B. Reduction of TMAO level enhances the stability of carotid atherosclerotic plaque through promoting macrophage M2 polarization and efferocytosis. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, 1–13.

- Tan, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Zhou, P.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Song, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Plasma trimethylamine N-oxide as a novel biomarker for plaque rupture in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, 1–8.

- Kong, W.; Ma, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, W. Positive Association of Plasma Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Atherosclerosis in Patient with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 2022, 1–9.

- Zhu, W.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Buffa, J.A.; Gupta, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Mehrabian, M.; et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 2016, 165, 111–124.

- Xie, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yang, M.; Huang, D.; Zhao, P.; Tian, J.; Wang, X.; Hou, J. Remodelling of gut microbiota by Berberine attenuates trimethylamine N-oxide-induced platelet hyperreaction and thrombus formation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 911, 174526.

- Almesned, M.A.; Prins, F.M.; Lipšic, E.; Connelly, M.A.; Garcia, E.; Dullaart, R.P.F.; Groot, H.E.; van der Harst, P. Temporal course of plasma trimethylamine n-oxide (Tmao) levels in st-elevation myocardial infarction. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5677.

- Díez-Ricote, L.; Ruiz-Valderrey, P.; Micó, V.; Blanco, R.; Tomé-Carneiro, J.; Dávalos, A.; Ordovás, J.M.; Daimiel, L. TMAO Upregulates Members of the miR-17/92 Cluster and Impacts Targets Associated with Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12107.

- Díez-ricote, L.; Ruiz-Valderrey, P.; Micó, V.; Blanco-Rojo, R.; Carneiro, J.T.; Dávalos, A.; Ordovás, J.M.; Daimiel, L. Trimethylamine n-oxide (TMAO) modulates the expression of cardiovascular disease-related microRNAs and their targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11145.

- Coffey, A.R.; Kanke, M.; Smallwood, T.L.; Albright, J.; Pitman, W.; Gharaibeh, R.Z.; Hua, K.; Gertz, E.; Biddinger, S.B.; Temel, R.E.; et al. microRNA-146a-5p association with the cardiometabolic disease risk factor TMAO. Physiol. Genom. 2019, 51, 59–71.

- Liu, X.; Shao, Y.; Tu, J.; Sun, J.; Dong, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Chen, L.; Tao, J.; Chen, J. TMAO-Activated Hepatocyte-Derived Exosomes Impair Angiogenesis via Repressing CXCR4. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 1–13.

- Liu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Xun, S.; Sun, M. Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes atherosclerosis via regulating the enriched abundant transcript 1/miR-370-3p/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3/flavin-containing monooxygenase-3 axis. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 1541–1553.

- Shi, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Zhou, M.; Dai, M. Inhibiting vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation mediated by osteopontin via regulating gut microbial lipopolysaccharide: A novel mechanism for paeonol in atherosclerosis treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1–16.

- Loffredo, L.; Ivanov, V.; Ciobanu, N.; Deseatnicova, E.; Gutu, E.; Mudrea, L.; Ivanov, M.; Nocella, C.; Cammisotto, V.; Orlando, F.; et al. Is There an Association between Atherosclerotic Burden, Oxidative Stress, and Gut-Derived Lipopolysaccharides? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 33, 761–766.

- Rehues, P.; Rodríguez, M.; Álvarez, J.; Jiménez, M.; Melià, A.; Sempere, M.; Balsells, C.; Castillejo, G.; Guardiola, M.; Castro, A.; et al. Characterization of the lps and 3ohfa contents in the lipoprotein fractions and lipoprotein particles of healthy men. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 47.

- Xiao, Q.; Zhu, X.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Yin, R.; Song, J.; Ma, A.; Pan, X. LPS induces CXCL16 expression in HUVECs through the miR-146a-mediated TLR4 pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 69, 143–149.

- Suzuki, K.; Ohkuma, M.; Nagaoka, I. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide and antimicrobial LL-37 enhance ICAM-1 expression and NF-κB p65 phosphorylation in senescent endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 1187–1196.

- Yu, S.; Chen, X.; Xiu, M.; He, F.; Xing, J.; Min, D.; Guo, F. The regulation of Jmjd3 upon the expression of NF-κB downstream inflammatory genes in LPS activated vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 485, 62–68.

- Hashimoto, R.; Kakigi, R.; Miyamoto, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Itoh, S.; Daida, H.; Okada, T.; Katoh, Y. JAK-STAT-dependent regulation of scavenger receptors in LPS-activated murine macrophages. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 871, 172940.

- Hashimoto, R.; Kakigi, R.; Nakamura, K.; Itoh, S.; Daida, H.; Okada, T.; Katoh, Y. LPS enhances expression of CD204 through the MAPK/ERK pathway in murine bone marrow macrophages. Atherosclerosis 2017, 266, 167–175.

- Hossain, E.; Ota, A.; Karnan, S.; Takahashi, M.; Mannan, S.B.; Konishi, H.; Hosokawa, Y. Lipopolysaccharide augments the uptake of oxidized LDL by up-regulating lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 in macrophages. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 400, 29–40.

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, D.; Wang, J.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, Z. Adipophilin involved in lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in RAW264.7 cell via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma pathway. DNA Cell Biol. 2017, 36, 1159–1167.

- Lin, L.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, H.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Y. Myocardin-Related Transcription Factor A Mediates LPS-Induced iNOS Transactivation. Inflammation 2020, 43, 1351–1361.

- Zhu, C.; Zhou, J.; Li, T.; Mu, J.; Jin, L.; Li, S. Urocortin participates in LPS-induced apoptosis of THP-1 macrophages via S1P-cPLA2 signaling pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 887, 173559.

- Yaker, L.; Tebani, A.; Lesueur, C.; Dias, C.; Jung, V.; Bekri, S.; Guerrera, I.C.; Kamel, S.; Ausseil, J.; Boullier, A. Extracellular Vesicles From LPS-Treated Macrophages Aggravate Smooth Muscle Cell Calcification by Propagating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1–18.

- Feng, J.; Li, A.; Deng, J.; Yang, Y.; Dang, L.; Ye, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. MiR-21 attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced lipid accumulation and inflammatory response: Potential role in cerebrovascular disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2014, 13, 1–9.

- Yu, M.H.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Mo, S.J.; Ni, Y.; Han, F.; Wang, Y.-B.; Tu, Y.X. SAA1 increases NOX4/ROS production to promote LPS-induced inflammation in vascular smooth muscle cells through activating p38MAPK/NF-κB pathway. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 1–11.

- Quellec, A.L.E.; Kervran, A.; Blache, P.; Ciurana, A.; Bataille, D. Oxyntomodulin-Like Immunoreactivity: Diurnal Profile of a New Potential Enterogastrone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1992, 74, 1405–1409.

- Correale, M.; Lamacchia, O.; Ciccarelli, M.; Dattilo, G.; Tricarico, L.; Brunetti, N.D. Vascular and metabolic effects of SGLT2i and GLP-1 in heart failure patients. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 1–12.

- Yaribeygi, H.; Maleki, M.; Sathyapalan, T.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Incretin-based therapies and renin-angiotensin system: Looking for new therapeutic potentials in the diabetic milieu. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117916.

- Hiromura, M.; Mori, Y.; Kohashi, K.; Terasaki, M.; Shinmura, K.; Negoro, T.; Kawashima, H.; Kogure, M.; Wachi, T.; Watanabe, R.; et al. Suppressive effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide on cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in angiotensin II-infused mouse models. Circ. J. 2016, 80, 1988–1997.

- Li, R.; Shan, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, F. The GLP-1 analog liraglutide protects against angiotensin II and pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy via PI3K/AKT1 and AMPKa signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1–15.

- Aoyama, M.; Kawase, H.; Bando, Y.K.; Monji, A.; Murohara, T. Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibition Alleviates Shortage of Circulating Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 in Heart Failure and Mitigates Myocardial Remodeling and Apoptosis via the Exchange Protein Directly Activated by Cyclic AMP 1/Ras-Related Protein 1 Axis. Circ. Heart Fail. 2016, 9, 1–10.

- Packer, M. Do DPP-4 Inhibitors Cause Heart Failure Events by Promoting Adrenergically Mediated Cardiotoxicity? Clues from Laboratory Models and Clinical Trials. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 928–932.

- Poornima, I.; Brown, S.B.; Bhashyam, S.; Parikh, P.; Bolukoglu, H.; Shannon, R.P. Chronic glucagon-like peptide-1 infusion sustains left ventricular systolic function and prolongs survival in the spontaneously hypertensive, heart failure-prone rat. Circ. Heart Fail. 2008, 1, 153–160.

- Naruse, G.; Kanamori, H.; Yoshida, A.; Minatoguchi, S.; Kawaguchi, T.; Iwasa, M.; Yamada, Y.; Mikami, A.; Kawasaki, M.; Nishigaki, K.; et al. The intestine responds to heart failure by enhanced mitochondrial fusion through glucagon-like peptide-1 signalling. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1873–1885.

- Siraj, M.A.; Mundil, D.; Beca, S.; Momen, A.; Shikatani, E.A.; Afroze, T.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Ghaffari, S.; Lee, W.; et al. Cardioprotective GLP-1 metabolite prevents ischemic cardiac injury by inhibiting mitochondrial trifunctional protein-α. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1392–1404.

- Ussher, J.R.; Campbell, J.E.; Mulvihill, E.E.; Baggio, L.L.; Bates, H.E.; McLean, B.A.; Gopal, K.; Capozzi, M.; Yusta, B.; Cao, X.; et al. Inactivation of the Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Receptor Improves Outcomes following Experimental Myocardial Infarction. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 450–460.e6.

- Timmers, L.; Henriques, J.P.S.; de Kleijn, D.P.V.; DeVries, J.H.; Kemperman, H.; Steendijk, P.; Verlaan, C.W.J.; Kerver, M.; Piek, J.J.; Doevendans, P.A.; et al. Exenatide Reduces Infarct Size and Improves Cardiac Function in a Porcine Model of Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 501–510.

- Lee, T.M.; Chen, W.T.; Chang, N.C. Sitagliptin decreases ventricular arrhythmias by attenuated glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)-dependent resistin signalling in infarcted rats. Biosci. Rep. 2016, 36, 1–10.

- McCormick, L.M.; Hoole, S.P.; White, P.A.; Read, P.A.; Axell, R.G.; Clarke, S.J.; O’Sullivan, M.; West, N.E.J.; Dutka, D.P. Pre-treatment with glucagon-like peptide-1 protects against ischemic left ventricular dysfunction and stunning without a detected difference in myocardial substrate utilization. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, 292–301.

- Read, P.A.; Khan, F.Z.; Dutka, D.P. Cardioprotection against ischaemia induced by dobutamine stress using glucagon-like peptide-1 in patients with coronary artery disease. Heart 2012, 98, 408–413.

- Nuamnaichati, N.; Mangmool, S.; Chattipakorn, N.; Parichatikanond, W. Stimulation of GLP-1 Receptor Inhibits Methylglyoxal-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunctions in H9c2 Cardiomyoblasts: Potential Role of Epac/PI3K/Akt Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1–16.

- Chen, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, F.; Shi, S.; Chen, Y.; Yang, B.; Tang, Y.; Huang, C. Exendin-4 inhibits structural remodeling and improves Ca2+ homeostasis in rats with heart failure via the GLP-1 receptor through the eNOS/cGMP/PKG pathway. Peptides 2017, 90, 69–77.

- Robinson, E.; Cassidy, R.S.; Tate, M.; Zhao, Y.; Lockhart, S.; Calderwood, D.; Church, R.; McGahon, M.K.; Brazil, D.P.; McDermott, B.J.; et al. Exendin-4 protects against post-myocardial infarction remodelling via specific actions on inflammation and the extracellular matrix. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2015, 110, 1–15.

- Robinson, E.; Tate, M.; Lockhart, S.; McPeake, C.; O’Neill, K.M.; Edgar, K.S.; Calderwood, D.; Green, B.D.; McDermott, B.J.; Grieve, D.J. Metabolically-inactive glucagon-like peptide-1(9-36)amide confers selective protective actions against post-myocardial infarction remodelling. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2016, 15, 1–11.

- Nguyen, T.D.; Shingu, Y.; Amorim, P.A.; Schenkl, C.; Schwarzer, M.; Doenst, T. GLP-1 Improves Diastolic Function and Survival in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2018, 11, 259–267.

- Bostick, B.; Habibi, J.; Ma, L.; Aroor, A.; Rehmer, N.; Hayden, M.R.; Sowers, J.R. Dipeptidyl peptidase inhibition prevents diastolic dysfunction and reduces myocardial fibrosis in a mouse model of Western diet induced obesity. Metabolism 2014, 63, 1000–1011.

- Warbrick, I.; Rabkin, S.W. Effect of the peptides Relaxin, Neuregulin, Ghrelin and Glucagon-like peptide-1, on cardiomyocyte factors involved in the molecular mechanisms leading to diastolic dysfunction and/or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Peptides 2019, 111, 33–41.

- Gupta, S.; Mitra, A. Heal the heart through gut (hormone) ghrelin: A potential player to combat heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 26, 417–435.

- Chen, Y.; Ji, X.-w.; Zhang, A.-y.; Lv, J.-c.; Zhang, J.-g.; Zhao, C.-h. Prognostic Value of Plasma Ghrelin in Predicting the Outcome of Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Arch. Med. Res. 2014, 45, 263–269.

- Nagaya, N.; Masaaki, U.; Kojima, M.; Date, Y.; Nakazato, M.; Okumura, H.; Hosoda, H.; Shimizu, W.; Yamagishi, M.; Oya, H.; et al. Elevated Circulating Level of Ghrelin in Cachexia Associated With Chronic Heart Failure Relationships Between Ghrelin and Anabolic/Catabolic Factors. Circulation 2001, 104, 2034–2038.

- Aleksova, A.; Beltrami, A.P.; Bevilacqua, E.; Padoan, L.; Santon, D.; Biondi, F.; Barbati, G.; Stenner, E.; Cappellari, G.G.; Barazzoni, R.; et al. Ghrelin derangements in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: Impact of myocardial disease duration and left ventricular ejection fraction. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1152.

- Beiras-Fernandez, A.; Kreth, S.; Weis, F.; Ledderose, C.; Pöttinger, T.; Dieguez, C.; Beiras, A.; Reichart, B. Altered myocardial expression of ghrelin and its receptor (GHSR-1a) in patients with severe heart failure. Peptides 2010, 31, 2222–2228.

- Sullivan, R.; Randhawa, V.K.; Lalonde, T.; Yu, T.; Kiaii, B.; Luyt, L.; Wisenberg, G.; Dhanvantari, S. Regional Differences in the Ghrelin-Growth Hormone Secretagogue Receptor Signalling System in Human Heart Disease. CJC Open 2021, 3, 182–194.

- Gianfranco, M.; Powers, J.C.; Grifoni, G.; Woitek, F.; Lam, A.; Ly, L.; Settanni, F.; Makarewich, C.A.; McCormick, R.; Trovato, L.; et al. The Gut Hormone Ghrelin Partially Reverses Energy Substrate Metabolic Alterations in the Failing Heart. Circ. Heart Fail. 2014, 7, 643–651.

- Nagaya, N.; Moriya, J.; Yasumura, Y.; Uematsu, M.; Ono, F.; Shimizu, W.; Ueno, K.; Kitakaze, M.; Miyatake, K.; Kangawa, K. Effects of ghrelin administration on left ventricular function, exercise capacity, and muscle wasting in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 2004, 110, 3674–3679.

- Eid, R.A.; Alkhateeb, M.A.; Al-Shraim, M.; Eleawa, S.M.; Shatoor, A.S.; El-Kott, A.F.; Zaki, M.S.A.; Shatoor, K.A.; Bin-Jaliah, I.; Al-Hashem, F.H. Ghrelin prevents cardiac cell apoptosis during cardiac remodelling post experimentally induced myocardial infarction in rats via activation of Raf-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 signalling. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 125, 93–103.

- Eid, R.A.; Alkhateeb, M.A.; Eleawa, S.; Al-Hashem, F.H.; Al-Shraim, M.; El-kott, A.F.; Zaki, M.S.A.; Dallak, M.A.; Aldera, H. Cardioprotective effect of ghrelin against myocardial infarction-induced left ventricular injury via inhibition of SOCS3 and activation of JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2018, 113, 1–16.

- Yang, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Du, B.; Shi, K.; Ding, M.; Li, B.; Yang, P. Ghrelin suppresses cardiac fibrosis of post-myocardial infarction heart failure rats by adjusting the activin A-follistatin imbalance. Peptides 2018, 99, 27–35.

- Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Gui, Q.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, L.; Meng, J.; Qing, J.; Gao, L.; Jackson, A.O.; Feng, J.; et al. Ghrelin attenuates myocardial fibrosis after acute myocardial infarction via inhibiting endothelial-to mesenchymal transition in rat model. Peptides 2019, 111, 118–126.

- Wang, Q.; Liu, A.D.; Li, T.S.; Tang, Q.; Wang, X.C.; Chen, X. bin Ghrelin ameliorates cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction by regulating the Nrf2/NADPH/ROS pathway. Peptides 2021, 144, 170613.

- Eid, R.A.; Zaki, M.S.A.; Al-Shraim, M.; Eleawa, S.M.; El-kott, A.F.; Al-Hashem, F.H.; Eldeen, M.A.; Ibrahim, H.; Aldera, H.; Alkhateeb, M.A. Subacute ghrelin administration inhibits apoptosis and improves ultrastructural abnormalities in remote myocardium post-myocardial infarction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 920–928.

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Launikonis, B.S.; Chen, C. Growth hormone secretagogues preserve the electrophysiological properties of mouse cardiomyocytes isolated from in Vitro ischemia/reperfusion heart. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 5480–5490.

- Soeki, T.; Niki, T.; Uematsu, E.; Bando, S.; Matsuura, T.; Kusunose, K.; Ise, T.; Ueda, Y.; Tomita, N.; Yamaguchi, K.; et al. Ghrelin protects the heart against ischemia-induced arrhythmias by preserving connexin-43 protein. Heart Vessel. 2013, 28, 795–801.

- Mao, Y.; Tokudome, T.; Otani, K.; Kishimoto, I.; Nakanishi, M.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazato, M.; Kangawa, K. Ghrelin prevents incidence of malignant arrhythmia after acute myocardial infarction through vagal afferent nerves. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3426–3434.

- Mao, Y.; Tokudome, T.; Otani, K.; Kishimoto, I.; Miyazato, M.; Kangawa, K. Excessive sympathoactivation and deteriorated heart function after myocardial infarction in male ghrelin knockout mice. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 1854–1863.

- Wang, Q.; Lin, P.; Li, P.; Feng, L.; Ren, Q.; Xie, X.; Xu, J. Ghrelin protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibition of TLR4/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Life Sci. 2017, 186, 50–58.

- Fukunaga, N.; Ribeiro, R.V.P.; Bissoondath, V.; Billia, F.; Rao, V. Ghrelin May Inhibit Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis During Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Transplant. Proc. 2022, 54, 2357–2363.

- Sun, N.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. Protective effects of ghrelin against oxidative stress, inducible nitric oxide synthase and inflammation in a mouse model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via the HMGB1 and TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 2764–2770.

- Huynh, D.N.; Elimam, H.; Bessi, V.L.; Ménard, L.; Burelle, Y.; Granata, R.; Carpentier, A.C.; Ong, H.; Marleau, S. A linear fragment of unacylated ghrelin (UAG6−13) protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice in a growth hormone secretagogue receptor-independent manner. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 1–9.

- Wang, Q.; Sui, X.; Chen, R.; Ma, P.Y.; Teng, Y.L.; Ding, T.; Sui, D.J.; Yang, P. Ghrelin Ameliorates Angiotensin II-Induced Myocardial Fibrosis by Upregulating Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma in Young Male Rats. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9897581.

- Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, P. Ghrelin alleviates angiotensin ii-induced H9c2 apoptosis: Impact of the miR-208 family. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 6707–6716.

- Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, P. The impact of microRNA-122 and its target gene Sestrin-2 on the protective effect of ghrelin in angiotensin II-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 10107–10114.

- Lu, W.; Cai, H.; Chen, Y.; Liao, X.; Zhang, L.; Ma, T.; Sun, H.; Qi, Y. Ghrelin inhibited pressure overload–induced cardiac hypertrophy by promoting autophagy via CaMKK/AMPK signaling pathway. Peptides 2021, 136, 170446.

- Mao, Y.; Tokudome, T.; Kishimoto, I.; Otani, K.; Nishimura, H.; Yamaguchi, O.; Otsu, K.; Miyazato, M.; Kangawa, K. Endogenous Ghrelin Attenuates Pressure Overload-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy via a Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway. Hypertension 2015, 65, 1238–1244.

- Liu, Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Shen, Y.; Ye, C.F.; Hu, N.; Yao, Q.; Lv, X.Z.; Long, S.L.; Ren, C.; Lang, Y.Y.; et al. Ghrelin protects against obesity-induced myocardial injury by regulating the lncRNA H19/miR-29a/IGF-1 signalling axis. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2020, 114, 104405.

- Lang, Y.Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Liu, Y.L.; Ye, C.F.; Hu, N.; Yao, Q.; Cheng, W.S.; Cheng, Z.G.; Liu, Y. Ghrelin Relieves Obesity-Induced Myocardial Injury by Regulating the Epigenetic Suppression of miR-196b Mediated by lncRNA HOTAIR. Obes. Facts 2022, 15, 540–549.

- Pei, X.M.; Yung, B.Y.; Yip, S.P.; Chan, L.W.; Wong, C.S.; Ying, M.; Siu, P.M. Protective effects of desacyl ghrelin on diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Diabetol. 2015, 52, 293–306.

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.L.; Chen, H.L.; Wu, D.; Chen, J.X.; Wang, X.X.; Li, R.L.; He, J.H.; Mo, L.; Cen, X.; et al. Ghrelin inhibits doxorubicin cardiotoxicity by inhibiting excessive autophagy through AMPK and p38-MAPK. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 88, 334–350.

- Goetze, J.P.; Rehfeld, J.F.; Alehagen, U. Cholecystokinin in plasma predicts cardiovascular mortality in elderly females. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 209, 37–41.

- Dong, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Kang, Y.; Tian, S.; Fu, L. Cholecystokinin Expression in the Development of Postinfarction Heart Failure. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 2479–2488.

- Wang, C.; Zhang, C.; Wu, D.; Guo, L.; Zhao, F.; Lv, J.; Fu, L. Cholecystokinin octapeptide reduces myocardial fibrosis and improves cardiac remodeling in post myocardial infarction rats. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 125, 105793.

- Wang, C.; Yu, H.; Wei, L.; Zhang, J.; Hong, M.; Chen, L.; Dong, X.; Fu, L. Protective effect of cholecystokinin octapeptide on angiotensin II-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyoblast cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 121, 3560–3569.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ke, B.; Du, J. TMAO: How gut microbiota contributes to heart failure. Transl. Res. 2021, 228, 109–125.

- Tang, W.H.W.; Wang, Z. Prognostic Value of Elevated Levels of Intestinal Microbe Generated TMAO in patients with heart failure: Refining the gut hypothesis. Am. J. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 1908–1914.

- Trøseid, M.; Ueland, T.; Hov, J.R.; Svardal, A.; Gregersen, I.; Dahl, C.P.; Aakhus, S.; Gude, E.; Bjørndal, B.; Halvorsen, B.; et al. Microbiota-dependent metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide is associated with disease severity and survival of patients with chronic heart failure. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 277, 717–726.

- Zong, X.; Fan, Q.; Yang, Q.; Pan, R.; Zhuang, L.; Xi, R.; Zhang, R.; Tao, R. Trimethyllysine, a trimethylamine N-oxide precursor, predicts the presence, severity, and prognosis of heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1–12.

- Suzuki, T.; Yazaki, Y.; Voors, A.A.; Jones, D.J.L.; Chan, D.C.S.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.; Hillege, H.L.; et al. Association with outcomes and response to treatment of trimethylamine N-oxide in heart failure: Results from BIOSTAT-CHF. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 877–886.

- Yuzefpolskaya, M.; Bohn, B.; Javaid, A.; Mondellini, G.M.; Braghieri, L.; Pinsino, A.; Onat, D.; Kim, A.; Takeda, K.; Naka, Y.; et al. Levels of Trimethylamine N-oxide Remain Elevated Long-Term After LVAD and Heart Transplantation and are Independent from Measures of Inflammation and Gut Dysbiosis. Circ. Heart Fail. 2021, 14, 1–28.

- Salzano, A.; Israr, M.Z.; Yazaki, Y.; Heaney, L.M.; Kanagala, P.; Singh, A.; Arnold, J.R.; Gulsin, G.S.; Squire, I.B.; McCann, G.P.; et al. Combined use of trimethylamine N-oxide with BNP for risk stratification in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Findings from the DIAMONDHFpEF study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 2159–2162.

- Drapala, A.; Szudzik, M.; Chabowski, D.; Mogilnicka, I.; Jaworska, K.; Kraszewska, K.; Samborowska, E.; Ufnal, M. Heart failure disturbs gut–blood barrier and increases plasma trimethylamine, a toxic bacterial metabolite. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6161.

- Organ, C.L.; Otsuka, H.; Bhushan, S.; Wang, Z.; Bradley, J.; Trivedi, R.; Polhemus, D.J.; Wilson Tang, W.H.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L.; et al. Choline Diet and Its Gut Microbe—Derived Metabolite, Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO), Exacerbate Pressure Overload—Induced Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2016, 9, e002314.

- Li, Z.; Wu, Z.; Yan, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Ou, C.; Chen, M. Gut microbe-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide induces cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Lab. Investig. 2019, 99, 346–357.

- Chen, K.; Zheng, X.; Feng, M.; Li, D.; Zhang, H. Gut microbiota-dependent metabolite Trimethylamine N-oxide contributes to cardiac dysfunction in western diet-induced obese mice. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 139.

- Savi, M.; Bocchi, L.; Bresciani, L.; Falco, A.; Quaini, F.; Mena, P.; Brighenti, F.; Crozier, A.; Stilli, D.; Del Rio, D. Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)-induced impairment of cardiomyocyte function and the protective role of urolithin B-glucuronide. Molecules 2018, 23, 549.

- Huc, T.; Drapala, A.; Gawrys, M.; Konop, M.; Bielinska, K.; Zaorska, E.; Samborowska, E.; Wyczalkowska-Tomasik, A.; Pączek, L.; Dadlez, M.; et al. Chronic, low-dose TMAO treatment reduces diastolic dysfunction and heart fibrosis in hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H1805–H1820.

- Videja, M.; Vilskersts, R.; Korzh, S.; Cirule, H.; Sevostjanovs, E.; Dambrova, M.; Makrecka-Kuka, M. Microbiota-Derived Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide Protects Mitochondrial Energy Metabolism and Cardiac Functionality in a Rat Model of Right Ventricle Heart Failure. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 622741.

- Makrecka-Kuka, M.; Volska, K.; Antone, U.; Vilskersts, R.; Grinberga, S.; Bandere, D.; Liepinsh, E.; Dambrova, M. Trimethylamine N-oxide impairs pyruvate and fatty acid oxidation in cardiac mitochondria. Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 267, 32–38.

- Ebner, N.; Földes, G.; Schomburg, L.; Renko, K.; Springer, J.; Jankowska, E.A.; Sharma, R.; Genth-Zotz, S.; Doehner, W.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide responsiveness is an independent predictor of death in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 87, 48–53.

- Sandek, A.; Bjarnason, I.; Volk, H.D.; Crane, R.; Meddings, J.B.; Niebauer, J.; Kalra, P.R.; Buhner, S.; Herrmann, R.; Springer, J.; et al. Studies on bacterial endotoxin and intestinal absorption function in patients with chronic heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 157, 80–85.

- Strand, M.E.; Aronsen, J.M.; Braathen, B.; Sjaastad, I.; Kvaløy, H.; Tønnessen, T.; Christensen, G.; Lunde, I.G. Shedding of syndecan-4 promotes immune cell recruitment and mitigates cardiac dysfunction after lipopolysaccharide challenge in mice. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 88, 133–144.

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Du, A.; Zhu, X.; Yu, B. miR-203 accelerates apoptosis and inflammation induced by LPS via targeting NFIL3 in cardiomyocytes. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 6605–6613.

- Zhu, W.; Peng, F.; Cui, X.; Li, J.; Sun, C. LncRNA SOX2OT facilitates LPS-induced inflammatory injury by regulating intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) via sponging miR-215-5p. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 238, 109006.

- Magi, S.; Nasti, A.A.; Gratteri, S.; Castaldo, P.; Bompadre, S.; Amoroso, S.; Lariccia, V. Gram-negative endotoxin lipopolysaccharide induces cardiac hypertrophy: Detrimental role of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 746, 31–40.

- Hobai, I.A.; Buys, E.S.; Morse, J.C.; Edgecomb, J.; Weiss, E.H.; Armoundas, A.A.; Hou, X.; Khandelwal, A.R.; Siwik, D.A.; Brouckaert, P.; et al. SERCA Cys674 sulphonylation and inhibition of L-type Ca2+ influx contribute to cardiac dysfunction in endotoxemic mice, independent of cGMP synthesis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 305, 1189–1200.

- Katare, P.B.; Nizami, H.L.; Paramesha, B.; Dinda, A.K.; Banerjee, S.K. Activation of toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) promotes cardiomyocyte apoptosis through SIRT2 dependent p53 deacetylation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–15.

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Z.Y.; Wang, M.M.; Liu, X.M.; Gao, T.; Hu, Q.K.; Yuan, W.J.; Lin, L. Up-regulated TLR4 in cardiomyocytes exacerbates heart failure after long-term myocardial infarction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 2728–2740.

- Chen, L.C.; Shibu, M.A.; Liu, C.J.; Han, C.K.; Ju, D.T.; Chen, P.Y.; Viswanadha, V.P.; Lai, C.H.; Kuo, W.W.; Huang, C.Y. ERK1/2 mediates the lipopolysaccharide-induced upregulation of FGF-2, uPA, MMP-2, MMP-9 and cellular migration in cardiac fibroblasts. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 306, 62–69.

- Lew, W.Y.W.; Bayna, E.; Dalle Molle, E.; Contu, R.; Condorelli, G.; Tang, T. Myocardial fibrosis induced by exposure to subclinical lipopolysaccharide is associated with decreased miR-29c and enhanced NOX2 expression in mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 3–10.

- Gawałko, M.; Agbaedeng, T.A.; Saljic, A.; Müller, D.N.; Wilck, N.; Schnabel, R.; Penders, J.; Rienstra, M.; van Gelder, I.; Jespersen, T.; et al. Gut microbiota, dysbiosis and atrial fibrillation. Arrhythmogenic mechanisms and potential clinical implications. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2415–2427.

- Svingen, G.F.T.; Zuo, H.; Ueland, P.M.; Seifert, R.; Løland, K.H.; Pedersen, E.R.; Schuster, P.M.; Karlsson, T.; Tell, G.S.; Schartum-Hansen, H.; et al. Increased plasma trimethylamine-N-oxide is associated with incident atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 267, 100–106.

- Zuo, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Jiao, J.; Han, C.; Liu, Z.; Yin, X.; Li, J.; Yang, X. Metagenomic data-mining reveals enrichment of trimethylamine-N-oxide synthesis in gut microbiome in atrial fibrillation patients. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 1–9.

- Papandreou, C.; Bulló, M.; Hernández-Alonso, P.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Li, J.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Toledo, E.; Clish, C.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; et al. Choline Metabolism and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure in the PREDIMED Study. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 288–297.

- Yu, L.; Meng, G.; Huang, B.; Zhou, X.; Stavrakis, S.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. A potential relationship between gut microbes and atrial fibrillation: Trimethylamine N-oxide, a gut microbe-derived metabolite, facilitates the progression of atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 255, 92–98.

- Pastori, D.; Ettorre, E.; Carnevale, R.; Nocella, C.; Bartimoccia, S.; Del Sordo, E.; Cammisotto, V.; Violi, F.; Pignatelli, P.; Saliola, M.; et al. Interaction between serum endotoxemia and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) in patients with atrial fibrillation: A post-hoc analysis from the ATHERO-AF cohort. Atherosclerosis 2019, 289, 195–200.

- Menichelli, D.; Carnevale, R.; Nocella, C.; Cammisotto, V.; Castellani, V.; Bartimoccia, S.; Frati, G.; Pignatelli, P.; Pastori, D. Circulating Lipopolysaccharides and Impaired Antioxidant Status in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Data From the ATHERO-AF Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 1–7.

- Wang, M.; Xiong, H.; Lu, L.; Zhu, T.; Jiang, H. Serum Lipopolysaccharide Is Associated with the Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation after Radiofrequency Ablation by Increasing Systemic Inflammation and Atrial Fibrosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2405972.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, B.; Luo, Y.; Gong, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhuo, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis promotes age-related atrial fibrillation by lipopolysaccharide and glucose-induced activation of NLRP3-inflammasome. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 785–797.

- Sun, Z.; Zhou, D.; Xie, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Xu, H.; Zheng, L. Cross-talk between macrophages and atrial myocytes in atrial fibrillation. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2016, 111, 1–19.

- Chen, Y.Y.; Sun, Z.W.; Jiang, J.P.; Kang, X.D.; Wang, L.L.; Shen, Y.L.; Xie, X.D.; Zheng, L.R. A-Adrenoceptor-Mediated Enhanced Inducibility of Atrial Fibrillation in a Canine System Inflammation Model. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 3767–3774.