| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kohei Okuyama | -- | 2798 | 2023-02-20 17:55:12 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 2798 | 2023-02-21 01:58:44 | | |

Video Upload Options

Tumor budding (TB), a microscopic finding in the stroma ahead of the invasive fronts of tumors, has been well investigated and reported as a prognostic marker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a crucial step in tumor progression and metastasis, and its status cannot be distinguished from TB. The current understanding of partial EMT (p-EMT), the so-called halfway step of EMT, focuses on the tumor microenvironment (TME). Although this evidence has been investigated, the clinicopathological and biological relationship between TB and p-EMT remains debatable. At the invasion front, previous research suggested that cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are important for tumor progression, metastasis, p-EMT, and TB formation in the TME.

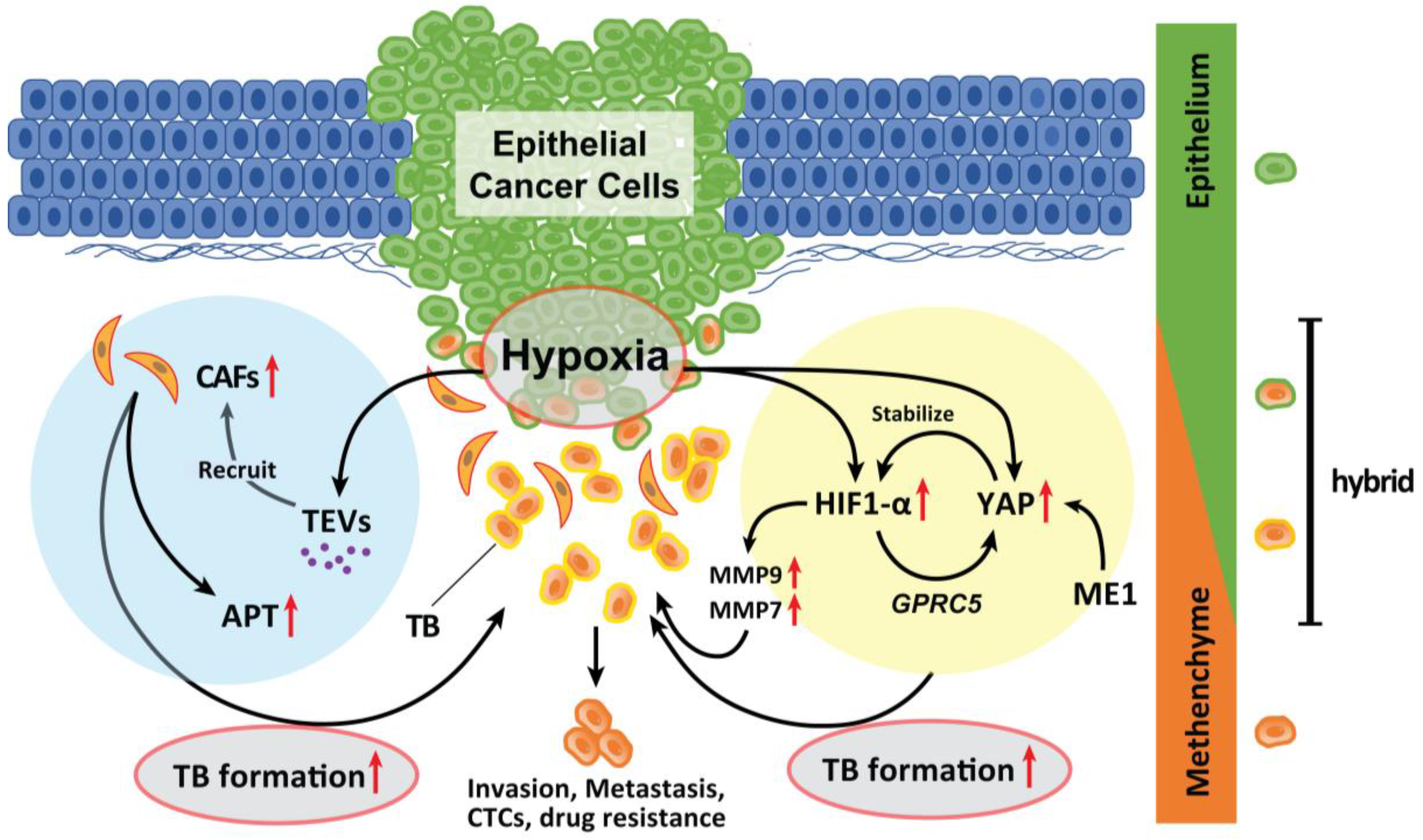

1. Hypoxia

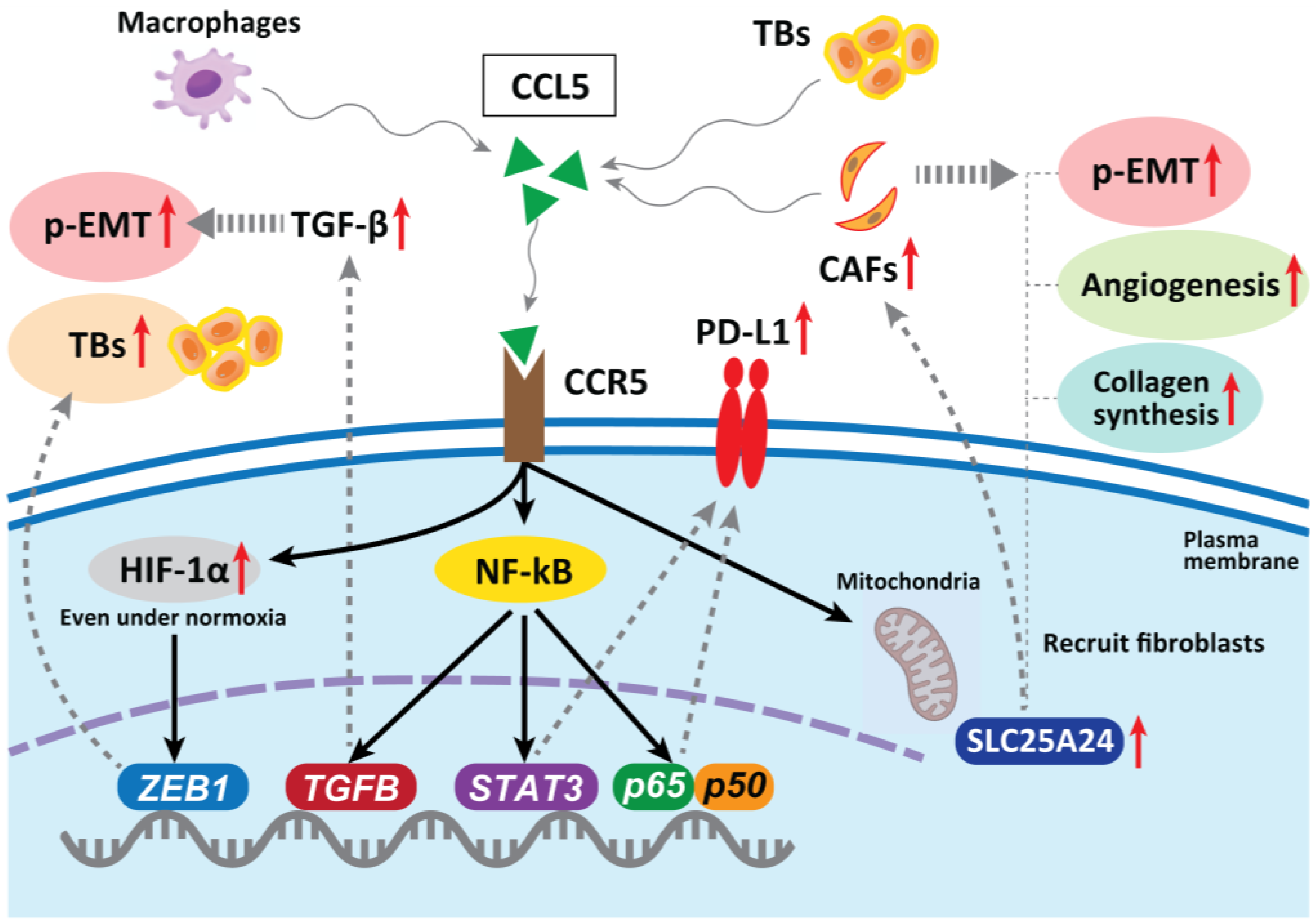

2. CAFs

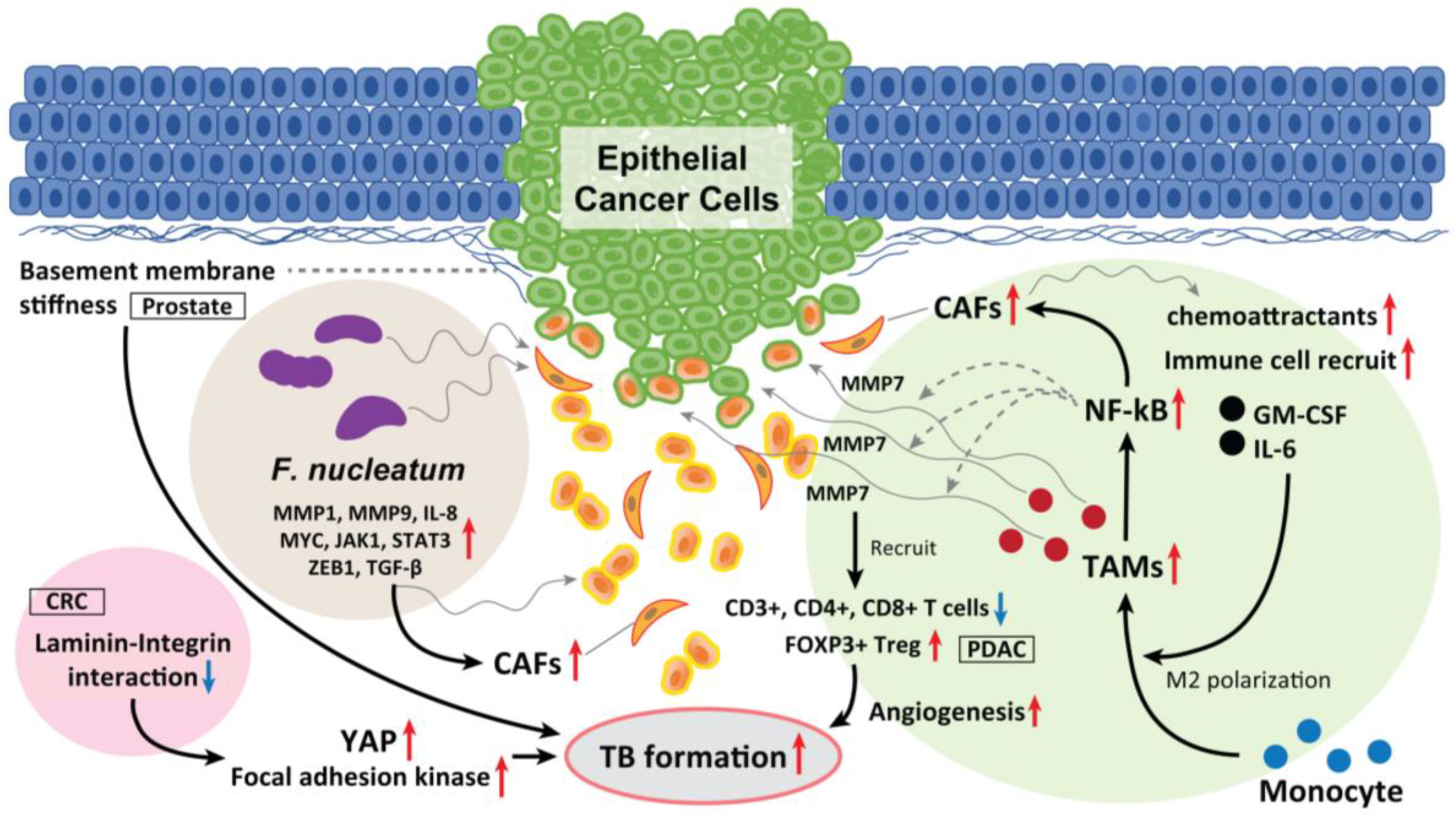

3. Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs)

4. Laminin-5γ2 (LN-5γ2) and Integrin β1

5. Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum)

6. Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Status

7. Methylthioadenosine Phosphorylase (MTAP)

| TB Driver | Mechanism | Cancer Type | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL4A1/COL13A1 | Activation of intracellular AKT pathway leads to an E/N-cadherin switch | Urothelial carcinoma of bladder | 2017 | [57] |

| SerpinE1 (known as plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1) | Regulation of the plasminogen activator system | HNSCC | 2019 | [58] |

| c-MET | Upregulation of MET transcription | CRC | 2016 | [52] |

| Tenascin-C | Tenascin-C induces cancer cell EMT-like change | CRC | 2018 | [53] |

| SREBP1 | Upregulation of MMP7expression and NF-κB pathway activation | CRC | 2019 | [54] |

| Increased tumor stroma Percentage and LDH-5 |

Decrease CD3+ lymphocyte stromal density | CRC | 2019 | [55] |

| Thymosin β4/β10 | Modulation of cytoskeleton organization | CRC | 2021 | [56] |

References

- Wong, C.C.; Kai, A.K.; Ng, I.O. The impact of hypoxia in hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Front. Med. 2014, 8, 33–41.

- Nakashima, C.; Kirita, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Mori, S.; Luo, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Fujii, K.; Ohmori, H.; Kawahara, I.; Mori, T.; et al. Malic Enzyme 1 Is Associated with Tumor Budding in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7149.

- Nakashima, C.; Yamamoto, K.; Kishi, S.; Sasaki, T.; Ohmori, H.; Fujiwara-Tani, R.; Mori, S.; Kawahara, I.; Nishiguchi, Y.; Mori, T.; et al. Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin induces claudin-4 to activate YAP in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 309–321.

- Greenhough, A.; Bagley, C.; Heesom, K.J.; Gurevich, D.B.; Gay, D.; Bond, M.; Collard, T.J.; Paraskeva, C.; Martin, P.; Sansom, O.J.; et al. Cancer cell adaptation to hypoxia involves a HIF-GPRC5A-YAP axis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, e8699.

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, T.; Meng, X.; Zong, Z.; Sun, X.; Hua, X.; Li, H. Yes-associated protein (YAP) binds to HIF-1α and sustains HIF-1α protein stability to promote hepatocellular carcinoma cell glycolysis under hypoxic stress. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 216.

- Guzińska-Ustymowicz, K. MMP-9 and cathepsin B expression in tumor budding as an indicator of a more aggressive phenotype of colorectal cancer (CRC). Anticancer Res. 2006, 26, 1589–1594.

- Masaki, T.; Matsuoka, H.; Sugiyama, M.; Abe, N.; Goto, A.; Sakamoto, A.; Atomi, Y. Matrilysin (MMP-7) as a significant determinant of malignant potential of early invasive colorectal carcinomas. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 84, 1317–1321.

- Nascimento, G.J.F.D.; Silva, L.P.D.; Matos, F.R.; Silva, T.A.D.; Medeiros, S.R.B.; Souza, L.B.; Freitas, R.A. Polymorphisms of matrix metalloproteinase-7 and -9 are associated with oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Braz. Oral Res. 2020, 35, e019.

- King, H.W.; Michael, M.Z.; Gleadle, J.M. Hypoxic enhancement of exosome release by breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 421.

- Montecalvo, A.; Larregina, A.T.; Shufesky, W.J.; Beer Stolz, D.; Sullivan, M.L.; Karlsson, J.M.; Baty, C.J.; Gibson, G.A.; Erdos, G.; Wang, Z.; et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood 2012, 119, 756–766.

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dai, X.; Li, W.; Cai, X.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xue, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Microvesicle-mediated transfer of microRNA-150 from monocytes to endothelial cells promotes angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 23586–23596.

- Quante, M.; Tu, S.P.; Tomita, H.; Gonda, T.; Wang, S.S.; Takashi, S.; Baik, G.H.; Shibata, W.; DiPrete, B.; Betz, K.S.; et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 257–272.

- Wang, H.X.; Gires, O. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles in breast cancer: From bench to bedside. Cancer Lett. 2019, 460, 54–64.

- Zhou, J.; Schwenk-Zieger, S.; Kranz, G.; Walz, C.; Klauschen, F.; Dhawan, S.; Canis, M.; Gires, O.; Haubner, F.; Baumeister, P.; et al. Isolation and characterization of head and neck cancer-derived peritumoral and cancer-associated fibroblasts. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 984138.

- Wang, J.; Min, A.; Gao, S.; Tang, Z. Genetic regulation and potentially therapeutic application of cancer-associated fibroblasts in oral cancer. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2014, 43, 323–334.

- Xu, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, Z.; Liu, R.; Lu, R.; Yao, Z.; Xu, Q. Cancer associated fibroblast-derived CCL5 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through activating HIF1α/ZEB1 axis. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 478.

- Chang, L.Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Mahalingam, J.; Huang, C.T.; Chen, T.W.; Kang, C.W.; Peng, H.M.; Chu, Y.Y.; Chiang, J.M.; Dutta, A.; et al. Tumor-derived chemokine CCL5 enhances TGF-β-mediated killing of CD8(+) T cells in colon cancer by T-regulatory cells. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 1092–1102.

- Aldinucci, D.; Borghese, C.; Casagrande, N. The CCL5/CCR5 Axis in Cancer Progression. Cancers 2020, 12, 1765.

- Aldinucci, D.; Colombatti, A. The inflammatory chemokine CCL5 and cancer progression. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 292376.

- Mielcarska, S.; Kula, A.; Dawidowicz, M.; Kiczmer, P.; Chrabańska, M.; Rynkiewicz, M.; Wziątek-Kuczmik, D.; Świętochowska, E.; Waniczek, D. Assessment of the RANTES Level Correlation and Selected Inflammatory and Pro-Angiogenic Molecules Evaluation of Their Influence on CRC Clinical Features: A Preliminary Observational Study. Medicina 2022, 58, 203.

- Okuyama, K.; Yanamoto, S. TMEM16A as a potential treatment target for head and neck cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 196.

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, C.; Fu, Y.; Luo, Y. High expression of CCR5 in melanoma enhances epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis via TGFβ1. J. Pathol. 2019, 247, 481–493.

- Bronsert, P.; Enderle-Ammour, K.; Bader, M.; Timme, S.; Kuehs, M.; Csanadi, A.; Kayser, G.; Kohler, I.; Bausch, D.; Hoeppner, J.; et al. Cancer cell invasion and EMT marker expression: A three-dimensional study of the human cancer-host interface. J. Pathol. 2014, 234, 410–422.

- Gao, L.F.; Zhong, Y.; Long, T.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.X.; Wang, X.Y.; Hu, Z.Y.; Li, Z.G. Tumor bud-derived CCL5 recruits fibroblasts and promotes colorectal cancer progression via CCR5-SLC25A24 signaling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 81.

- Chuang, J.Y.; Yang, W.H.; Chen, H.T. CCL5/CCR5 axis promotes the motility of human oral cancer cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2009, 220, 418–426.

- Lang, S.; Lauffer, L.; Clausen, C.; Löhr, I.; Schmitt, B.; Hölzel, D.; Wollenberg, B.; Gires, O.; Kastenbauer, E.; Zeidler, R. Impaired monocyte function in cancer patients: Restoration with a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 286–288.

- Li, C.; Chen, S.; Liu, C.; Mo, C.; Gong, W.; Hu, J.; He, M.; Xie, L.; Hou, X.; Tang, J.; et al. CCR5 as a prognostic biomarker correlated with immune infiltrates in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by bioinformatic study. Hereditas 2022, 159, 37.

- González-Arriagada, W.A.; Lozano-Burgos, C.; Zúñiga-Moreta, R.; González-Díaz, P.; Coletta, R.D. Clinicopathological significance of chemokine receptor (CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, CCR5, CCR7 and CXCR4) expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 755–763.

- Trumpi, K.; Frenkel, N.; Peters, T.; Korthagen, N.M.; Jongen, J.M.; Raats, D.; van Grevenstein, H.; Backes, Y.; Moons, L.M.; Lacle, M.M.; et al. Macrophages induce “budding” in aggressive human colon cancer subtypes by protease-mediated disruption of tight junctions. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 19490–19507.

- Wang, M.; Su, Z.; Amoah Barnie, P. Crosstalk among colon cancer-derived exosomes, fibroblast-derived exosomes, and macrophage phenotypes in colon cancer metastasis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 81, 106298.

- Xiao, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, W. M1-like tumor-associated macrophages activated by exosome-transferred THBS1 promote malignant migration in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 143.

- You, Y.; Tian, Z.; Du, Z.; Wu, K.; Xu, G.; Dai, M.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, M. M1-like tumor-associated macrophages cascade a mesenchymal/stem-like phenotype of oral squamous cell carcinoma via the IL6/Stat3/THBS1 feedback loop. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 10.

- Peixoto da-Silva, J.; Lourenço, S.; Nico, M.; Silva, F.H.; Martins, M.T.; Costa-Neves, A. Expression of laminin-5 and integrins in actinic cheilitis and superficially invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the lip. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2012, 208, 598–603.

- Marangon Junior, H.; Rocha, V.N.; Leite, C.F.; de Aguiar, M.C.F.; Souza, P.E.A.; Horta, M.C.R. Laminin-5 gamma 2 chain expression is associated with intensity of tumor budding and density of stromal myofibroblasts in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2014, 43, 199–204.

- Zhou, B.; Zong, S.; Zhong, W.; Tian, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Li, L.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J.; et al. Interaction between laminin-5γ2 and integrin β1 promotes the tumor budding of colorectal cancer via the activation of Yes-associated proteins. Oncogene 2020, 39, 1527–1542.

- Fiore, V.F.; Krajnc, M.; Quiroz, F.G.; Levorse, J.; Pasolli, H.A.; Shvartsman, S.Y.; Fuchs, E. Mechanics of a multilayer epithelium instruct tumour architecture and function. Nature 2020, 585, 433–439.

- Wang, M.; Nagle, R.B.; Knudsen, B.S.; Rogers, G.C.; Cress, A.E. A basal cell defect promotes budding of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 104–110.

- Gholizadeh, P.; Eslami, H.; Kafil, H.S. Carcinogenesis mechanisms of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 89, 918–925.

- Al-Hebshi, N.N.; Nasher, A.T.; Maryoud, M.Y.; Homeida, H.E.; Chen, T.; Idris, A.M.; Johnson, N.W. Inflammatory bacteriome featuring Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified in association with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1834.

- Shao, W.; Fujiwara, N.; Mouri, Y.; Kisoda, S.; Yoshida, K.; Yoshida, K.; Yumoto, H.; Ozaki, K.; Ishimaru, N.; Kudo, Y. Conversion from epithelial to partial-EMT phenotype by Fusobacterium nucleatum infection promotes invasion of oral cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14943.

- Kostic, A.D.; Gevers, D.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Michaud, M.; Duke, F.; Earl, A.M.; Ojesina, A.I.; Jung, J.; Bass, A.J.; Tabernero, J.; et al. Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 292–298.

- Okuyama, K.; Yanamoto, S. Oral bacterial contributions to gingival carcinogenesis and progression. Cancer Prev. Res. 2023, in press.

- Harrandah, A.M.; Chukkapalli, S.S.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Progulske-Fox, A.; Chan, E.K.L. Fusobacteria modulate oral carcinogenesis and promote cancer progression. J. Oral Microbiol. 2020, 13, 1849493.

- Niño, J.L.G.; Wu, H.; LaCourse, K.D.; Kempchinsky, A.G.; Baryiames, A.; Barber, B.; Futran, N.; Houlton, J.; Sather, C.; Sicinska, E.; et al. Effect of the intratumoral microbiota on spatial and cellular heterogeneity in cancer. Nature 2022, 611, 810–817.

- Salama, A.M.; Momeni-Boroujeni, A.; Vanderbilt, C.; Ladanyi, M.; Soslow, R. Molecular landscape of vulvovaginal squamous cell carcinoma: New insights into molecular mechanisms of HPV-associated and HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 274–282.

- Cho, Y.A.; Kim, E.K.; Cho, B.C.; Koh, Y.W.; Yoon, S.O. Twist and Snail/Slug Expression in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Correlation with Lymph Node Metastasis. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 6307–6316.

- Prall, F.; Ostwald, C.; Weirich, V.; Nizze, H. p16(INK4a) promoter methylation and 9p21 allelic loss in colorectal carcinomas: Relation with immunohistochemical p16(INK4a) expression and with tumor budding. Hum. Pathol. 2006, 37, 578–585.

- Bertino, J.R.; Waud, W.R.; Parker, W.B.; Lubin, M. Targeting tumors that lack methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) activity: Current strategies. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 11, 627–632.

- Bataille, F.; Rogler, G.; Modes, K.; Poser, I.; Schuierer, M.; Dietmaier, W.; Ruemmele, P.; Mühlbauer, M.; Wallner, S.; Hellerbrand, C.; et al. Strong expression of methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) in human colon carcinoma cells is regulated by TCF1/-catenin. Lab. Investig. 2005, 85, 124–136.

- Zhong, Y.; Lu, K.; Zhu, S.; Li, W.; Sun, S. Characterization of methylthioadenosin phosphorylase (MTAP) expression in colorectal cancer. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 2082–2087.

- Amano, Y.; Matsubara, D.; Kihara, A.; Nishino, H.; Mori, Y.; Niki, T. Expression and localisation of methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) in oral squamous cell carcinoma and their significance in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Pathology 2022, 54, 294–301.

- Bradley, C.A.; Dunne, P.D.; Bingham, V.; McQuaid, S.; Khawaja, H.; Craig, S.; James, J.; Moore, W.L.; McArt, D.G.; Lawler, M.; et al. Transcriptional upregulation of c-MET is associated with invasion and tumor budding in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 78932–78945.

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Qi, W.; Cui, C.; Cui, Y.; Xuan, Y. Tenascin-C as a prognostic determinant of colorectal cancer through induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and proliferation. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2018, 105, 216–222.

- Gao, Y.; Nan, X.; Shi, X.; Mu, X.; Liu, B.; Zhu, H.; Yao, B.; Liu, X.; Yang, T.; Hu, Y.; et al. SREBP1 promotes the invasion of colorectal cancer accompanied upregulation of MMP7 expression and NF-κB pathway activation. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 685.

- Roseweir, A.K.; Clark, J.; McSorley, S.T.; van Wyk, H.C.; Quinn, J.A.; Horgan, P.G.; McMillan, D.C.; Park, J.H.; Edwards, J. The association between markers of tumour cell metabolism, the tumour microenvironment and outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 2320–2329.

- Olianas, A.; Serrao, S.; Piras, V.; Manconi, B.; Contini, C.; Iavarone, F.; Pichiri, G.; Coni, P.; Zorcolo, L.; Orrù, G.; et al. Thymosin β4 and β10 are highly expressed at the deep infiltrative margins of colorectal cancer—A mass spectrometry analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 7285–7296.

- Miyake, M.; Hori, S.; Morizawa, Y.; Tatsumi, Y.; Toritsuka, M.; Ohnishi, S.; Shimada, K.; Furuya, H.; Khadka, V.S.; Deng, Y.; et al. Collagen type IV alpha 1 (COL4A1) and collagen type XIII alpha 1 (COL13A1) produced in cancer cells promote tumor budding at the invasion front in human urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36099–36114.

- Arroyo-Solera, I.; Pavón, M.Á.; Leon, X.; Lopez, M.; Gallardo, A.; Céspedes, M.V.; Casanova, I.; Pallares, V.; López-Pousa, A.; Mangues, M.A.; et al. Effect of serpinE1 overexpression on the primary tumor and lymph node, and lung metastases in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 2019, 41, 429–439.