| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mohamad Hesam Shahrajabian | -- | 2014 | 2023-02-20 15:56:22 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 2014 | 2023-02-21 04:26:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

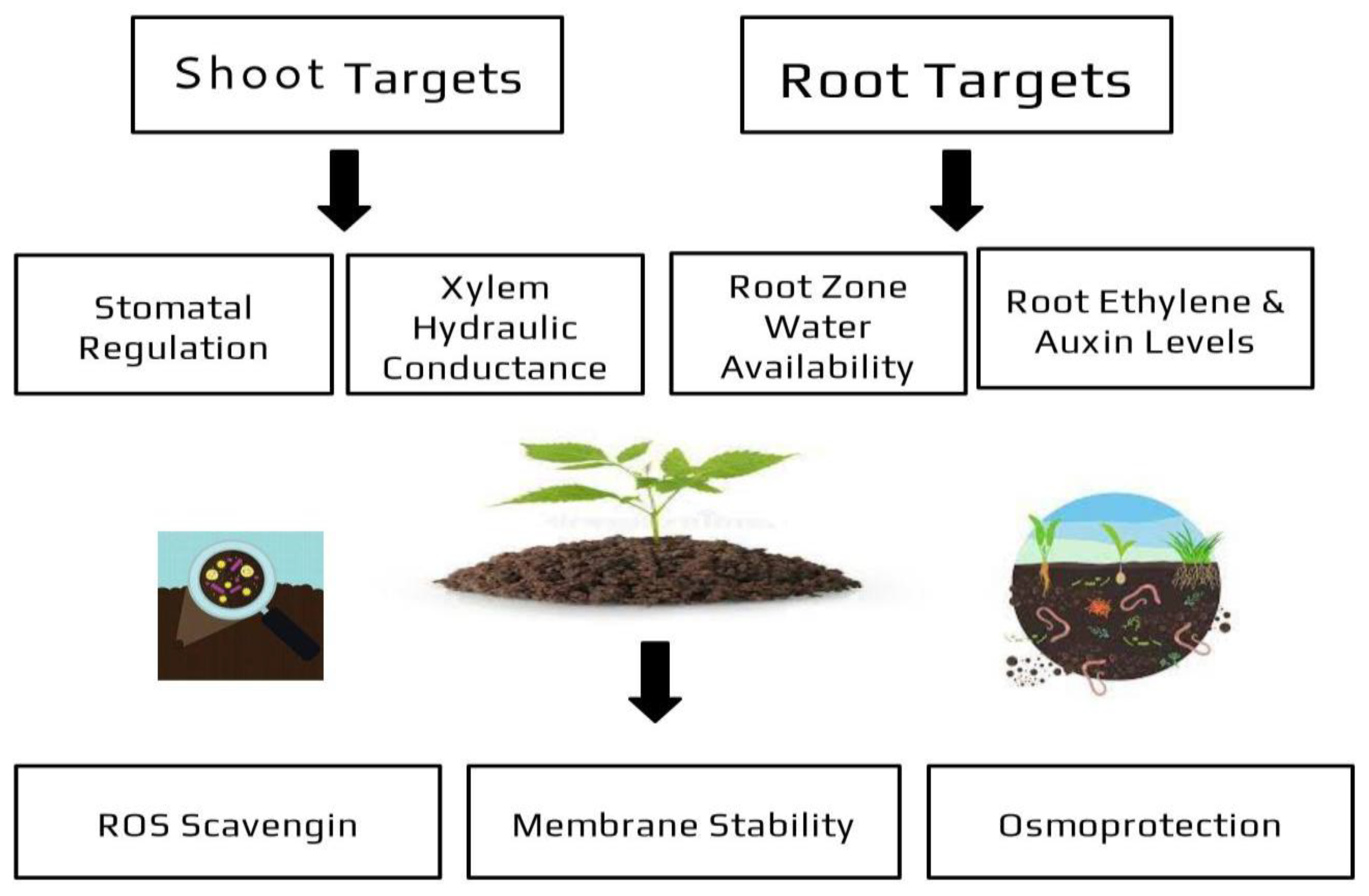

Sustainable farming of horticultural plants has been the focus of research during the last decade, paying significant attention to alarming weather extremities and climate change, as well as the pressure of biotic stressors on crops. Microbial biostimulants, including plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), have been proven to increase plant growth via both direct and indirect processes, as well as to increase the availability and uptake of nutrients, boosting soil quality, increasing plants’ tolerance to abiotic stress and increasing the overall quality attributes of various horticultural crops (e.g., vegetables, fruit, herbs). The positive effects of microbial biostimulants have been confirmed so far, mostly through symbiotic interactions in the plant–soil–microbes ecosystem, which are considered a biological tool to increase quality parameters of various horticultural crops as well as to decrease soil degradation.

1. Introduction

2. Modes of Action of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria

3. Modes of Action of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi

4. Indirect Effects of Microbial Biostimulants

| Stresses | Type of Stresses | Protective Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abiotic stress | |||

| Water stress | *Drought *Flooding |

*Osmolite production *Increase in antioxidant activity *Phytohormone level modulation *Secretion of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) |

[46][47][48] |

| Thermal stress | *Extreme heat *Freezing |

*Emission of volatile organic compounds *Photohormone level modulation *Ice-nucleatin activity antagonism *Osmo and thermal protection *Delay of senescence |

[37][38][39][40] |

| Nutrient stress | *Increased soil exploration *Mineral nutrients solubilization |

[35][36] | |

| Biotic stress | *Induced system resistance *Phytohormone level modulation *Direct antagonism with pathogens |

[8][14][15][16][17] |

References

- Kumar, M.; Poonam; Ahmad, S.; Singh, R. Plant Growth Promoting Microbes: Diverse Roles for Sustainable and Ecofriendly Agriculture. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100133.

- Kumari, M.; Swarupa, P.; Kesari, K.K.; Kumar, A. Microbial inoculants as plant biostimulants: A review on risk status. Life 2023, 13, 12.

- Joshi, M.; Parewa, H.P.; Joshi, S.; Sharma, J.K.; Shukla, U.N.; Paliwal, A.; Gupta, V. Chapter 5- Use of Microbial Biostimulants in Organic Farming. In Advances in Organic Farming; Meena, V.S., Meena, S.K., Srinivasarao, C., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2021; pp. 59–73.

- Ganugi, P.; Martinelli, E.; Lucini, L. Microbial biostimulants as a sustainable approach to improve the functional quality in plant-based foods: A review. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 41, 217–223.

- Mansoor, S.; Sharma, V.; Mir, M.A.; Mir, J.I.; Nabi, S.U.; Ahmed, N.; Alkahtani, J.; Alwahibi, M.S.; Masoodi, K.Z. Quantification of polyphenolic compounds and relative gene expression studies of phenylpropanoid pathway in apple (Malus domestica Borkh) in response to Venturia inaequalis infection. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 3397–3404.

- Heil, M.; Bostock, R. Induced systemic resistance (ISR) against pathogens in the contect of induced plant defences. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 503–512.

- Hamid, B.; Zaman, M.; Farooq, S.; Fatima, S.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Baba, Z.A.; Sheikh, T.A.; Reddy, M.S.; El Enshasy, H.; Gafur, A.; et al. Bacterial plant biostimulants: A sustainable way towards improving growth, productivity, and health of crops. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2856.

- Tanveer, Y.; Jahangir, S.; Shah, Z.A.; Yasmin, H.; Nosheen, A.; Hassan, M.N.; Illyas, N.; Bajguz, A.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Ahmad, P. Zinc oxide nanoparticles mediated biostimulant impact on cadmium detoxification and in silico analysis of zinc oxide-cadmium networks in Zea mays L. regulome. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 316, 120641.

- Vurukonda, S.S.K.P.; Vardharajula, S.; Shrivastava, M.; Skz, A. Enhancement of drought stress tolerance in crops by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 184, 13–24.

- Glick, B.R. Bacteria with ACC deaminase can promote plant growth and help to feed the world. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 30–39.

- Ayuso-Calles, M.; Garcia-Estevez, I.; Jimenez-Gomez, A.; Flores-Felix, J.D.; Escribano-Bailon, M.T.; Rivas, R. Rhizobium laguerreae improves productivity and phenolic content of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) under saline stress conditions. Foods 2020, 9, 1166.

- Rouphael, Y.; Lucini, L.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Colla, G.; Bonini, P.; Cardarelli, M. Metabolomic responses of maize shoots and roots elicited by combinatorial seed treatments with microbial and non-microbial biostimulants. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 664.

- Hashem, A.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Al-Arjani, A.-B.F.; Aldehaish, H.A.; Egamberdieva, D.; Allah, E.F.A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi regulate the oxidative system, hormones and ionic equilibrium to trigger salt stress tolerance in Cucumis sativus L. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1102–1114.

- Pellegrini, M.; Spera, D.; Ercole, C.; del Gallo, M. Allium cepa L. seed inoculation with a consortium of plant growth-promoting bacteria: Effects on plant growth and development and soil fertility status and microbial community. Proceedings 2020, 6, 20.

- Mangman, J.S.; Deaker, R.; Rogers, G. Optimal plant growth-promoting concentration of Azospirillum brasilense inoculated to cucumber, lettuce, and tomato seeds varies between bacterial strains. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2015, 62, 145–152.

- He, Y.; Pantigoso, H.A.; Wu, Z.; Vivanco, J.M. Co-inoculation of Bacillus sp. and Pseudomonas putida at different development stages acts as a biostimultant to promote growth, yield, and nutrient uptake of tomato. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 196–207.

- Kumar, P.; Erturk, V.S.; Almusawa, H. Mathematical structure of mosaic disease using microbial biostimulants via Caputo and Atangana-Baleanu derivatives. Results Phys. 2021, 24, 104186.

- Ruiu, L. Insect Pathogenic bacterial in integrated pest management. Insects 2015, 6, 352–367.

- Niu, D.D.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, L.; Jiang, C.H.; Zhou, D.M.; Guo, J.H. Application of PSX biocontrol preparation confers root-knot nematode management and increased fruit quality in tomato under field conditions. Biocont. Sci. Technol. 2016, 26, 174–180.

- Munhoz, L.D.; Fonteque, J.P.; Santos, I.M.O.; Navarro, M.O.P.; Simionato, A.S.; Goya, E.T.; Rezende, M.I.; Balbi-Pena, M.L.; de Oliveira, A.G.; Andrade, G. Control of bacterial stem rot on tomato by extracellular bioactive compounds produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa LV strain. Cogent Food Agric. 2017, 31, 1282592.

- Goutam, J.; Singh, R.; Vijayaraman, R.S.; Meena, M. Endophytic Fungi: Carrier of Potential Antioxidants. In Fungi and Their Role in Sustainable Development: Current Perspectives; Gehlot, P., Singh, J., Eds.; Springer: Sinagpore, 2018; pp. 539–551.

- Liu, K.; Garrett, C.; Fadamiro, H.; Kloepper, J.W. Induction of systemic resistance in Chinese cabbage against black rot by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Biol. Control. 2016, 99, 8–13.

- Shekoofeh, E.; Sepideh, H.; Roya, R. Role of mycorrhizal fungi and salicylic acid in salinity tolerance of Ocimum basilicum resistance to salinity. J. Biotech. 2012, 11, 2223–2235.

- Balliu, A.; Sallaku, G.; Rewald, B. AMF inoculation enhances growth and improves the nutrient uptake rates of transplanted, salt-stressed tomato seedlings. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15967–15981.

- Yuan, Z.L.; Zhang, C.L.; Lin, F.C. Role of diverse non-systemic fungal endophytes in plant performance and response to stress: Progress and approaches. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2010, 29, 116–126.

- Yang, H.; Han, X.; Liang, Y.; Ghosh, A.; Chen, J.; Tang, M. The combined effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and lead (Pb) stress on Pb accumulation, plant growth parameters, photosynthesis, and antioxidant enzymes in Robinia pseudoacacia L. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145726.

- Qun, H.Z.; Zing, H.C.; Bin, Z.Z.; Rong, Z.Z.; Song, W.H. Changes of antioxidative enzymes and cell membrane osmosis in tomato colonized by arbuscular mycorrhizae under NaCL stress. Coll. Surf. B Bioint. 2007, 59, 128–133.

- Iqbal, N.; Umar, S.; Khan, N.A. Nitrogen availability regulates proline and ethylene production and alleviates salinity stress in mustard (Brassica juncea). J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 178, 84–91.

- Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Zheng, J.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, C.; Zhang, X. Regulation of plant growth, photosynthesis, antioxidation and osmosis by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in watermelon seedlings under well-watered and drought conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 644.

- Parre, E.; Ghars, M.A.; Leprince, A.S.; Thiery, L.; Lefebvre, D.; Bordenave, M.; Richard, L.; Mazars, C.; Abdelly, C.; Savoure, A. Calcium signaling via phospholipase C is essential for proline accumulation upon ionic but not nonionic hyperosmotic stresses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 503–512.

- Yousuf, P.Y.; Ahmad, A.; Hemant Ganie, A.H.; Aref, I.M.; Iqbal, M. Potassium and calcium application ameliorates growth and oxidative homeostasis in salt-stressed Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) plants. Pak. J. Bot. 2015, 47, 1629–1639.

- Estrada, B.; Aroca, R.; Maathuis, F.J.M.; Barea, J.M.; Ruiz-Lozano, J.M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi native from a Mediterranean saline area enhance maize tolerance to salinity through improved ion homeostasis. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 1771–1782.

- Nephali, L.; Moodley, V.; Piater, L.; Steenkamp, P.; Buthelezi, N.; Dubery, I.; Burgess, K.; Huyser, J.; Tugizimana, F. A metabolomic landscape of mize plants treated with a microbial biostimulant under well-watered and drought conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 676632.

- Lephatsi, M.; Nephali, L.; Meyer, V.; Piater, L.A.; Buthelezi, N.; Dubery, I.A.; Opperman, H.; Brand, M.; Huyser, J.; Tugizimana, F. Molecular mechanisms associated with microbial biostimulant-mediated growth enhancement, priming and drought stress tolerance in maize plants. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10450.

- Romano, I.; Ventorino, V.; Pepe, O. Effectiveness of plant beneficial microbes: Overview of the methodological approaches for the assessment of root colonization and persistence. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 6.

- Bhalerao, R.P.; Eklof, J.; Ljung, K.; Marchant, A.; Bennett, M.; Sandberg, G. Shoot-derived auxin is essential for early lateral root emergence in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 2002, 29, 32–332.

- Theocharis, A.; Bordiec, S.; Fernandez, O.; Paquis, S.; Dhondt-Cordelier, S.; Baillieul, F.; Clément, C.; Barka, E.A. Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN Primes Vitis vinifera L. and Confers a Better Tolerance to Low Nonfreezing Temperatures. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2012, 25, 241–249.

- Tiryaki, D.; Aydin, I.; Atici, O. Psychrotolerant bacteria isolated from the lead apoplast of cold-adapted wild plants improve the cold resistance of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under low temperature. Cyrobiology 2019, 86, 111–119.

- Mishra, P.K.; Mishra, S.; Selvakumar, G.; Bisht, S.C.; Bisht, J.K.; Kundu, S.; Gupta, H.S. Characterisation of a psychrotolerant plant growth promotingPseudomonas sp. strain PGERs17 (MTCC 9000) isolated from North Western Indian Himalayas. Ann. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 561–568.

- Ali, S.Z.; Sandhya, V.; Grover, M.; Kishore, N.; Rao, L.V.; Venkateswarlu, B. Pseudomonas sp. strain AKM-P6 enhances tolerance of sorghum seedlings to elevated temperatures. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2009, 46, 45–55.

- Ali, S.Z.; Sandhya, V.; Grover, M.; Linga, V.R.; Bandi, V. Effect of inoculation with a thermotolerant plant growth promoting Pseudomonas putida strain AKMP7 on growth wheat (Triticum spp.) under heat stress. J. Plant Interact. 2011, 6, 239–246.

- Duc, N.H.; Csintalan, Z.; Posta, K. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi mitigate negative effects of combined drought and heat stress on tomato plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 132, 297–307.

- Park, Y.-G.; Mun, B.-G.; Kang, S.-M.; Hussain, A.; Shahzad, R.; Seo, C.-W.; Kim, A.-Y.; Lee, S.-U.; Oh, K.Y.; Lee, D.Y.; et al. Bacillus aryabhattai SRB02 tolerates oxidative and nitrosative stress and promotes the growth of soybean by modulating the production of phytohormones. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173203.

- Abd El-Daim, I.A.; Bejai, S.; Meijer, J. Improved heat stress tolerance of wheat seedlings by bacteria seed treatment. Plant Soil. 2014, 379, 337–350.

- Ruzzi, M.; Aroca, R. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria act as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 124–134.

- Lindow, S.E.; Brandl, M.T. Microbiology of the phyllosphere. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 1875–1883.

- Lim, J.H.; Kim, S.D. Induction of drought stress resistance by multi-functional PGPR Bacillus licheniformis K11 in pepper. Plant Pathology J. 2013, 29, 201–208.

- Saia, S.; Colla, G.; Raimondi, G.; Di Stasio, E.; Cardarelli, M.; Bonini, P.; Vitaglione, P.; De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y. An endophytic fungi-based biostimulant modulated lettuce yield, physiological and functional quality responses to both moderate and severe water limitation. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108595.

- Aroca, R.; Rosa, P.; Ruiz-Lozano, J.M. How does arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis regulate root hydraulic properties and plasma membrane aquaporins in Phaseolus vulgaris under drought, cold or salinity stresses? N. Phytol. 2007, 173, 808–816.

- Khan, A.L.; Hussain, J.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Al-Rawahi, A.; Lee, I.J. Endophytic fungi: Resource for gibberellins and crop abiotic stress resistance. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 62–76.

- Kang, S.M.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Khan, A.L.; Kim, M.J.; Park, J.M.; Kim, B.R.; Shin, D.H.; Lee, I.J. Gibberellin secreting rhizobacterium, Pseudomonas putida H-2-3 modulates the hormonal and stress physiology of soybean to improve the plant growth under saline and drought conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 84, 115–124.