| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reza Nejat | -- | 2674 | 2023-02-06 20:39:44 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -10 word(s) | 2664 | 2023-02-07 01:54:02 | | | | |

| 3 | Reza Nejat | + 10 word(s) | 2674 | 2023-02-07 17:26:44 | | | | |

| 4 | Reza Nejat | + 7 word(s) | 2681 | 2023-02-07 17:32:23 | | | | |

| 5 | Reza Nejat | + 101 word(s) | 2782 | 2023-02-11 16:32:36 | | | | |

| 6 | Reza Nejat | + 83 word(s) | 2865 | 2023-02-12 17:18:25 | | | | |

| 7 | Reza Nejat | + 7 word(s) | 2872 | 2023-02-12 21:29:37 | | | | |

| 8 | Reza Nejat | + 32 word(s) | 2904 | 2023-02-13 21:28:01 | | | | |

| 9 | Reza Nejat | + 1 word(s) | 2905 | 2023-02-13 21:29:05 | | | | |

| 10 | Reza Nejat | + 87 word(s) | 2992 | 2023-02-14 17:53:49 | | | | |

| 11 | Reza Nejat | Meta information modification | 2992 | 2023-02-14 17:54:55 | | | | |

| 12 | Reza Nejat | + 1 word(s) | 2993 | 2023-02-14 17:59:42 | | | | |

| 13 | Reza Nejat | Meta information modification | 2993 | 2023-02-14 18:22:31 | | | | |

| 14 | Reza Nejat | + 120 word(s) | 3113 | 2023-04-26 10:13:03 | | | | |

| 15 | Reza Nejat | + 87 word(s) | 3200 | 2023-04-26 14:05:05 | | | | |

| 16 | Reza Nejat | + 1 word(s) | 3201 | 2023-04-26 14:07:18 | | | | |

| 17 | Reza Nejat | -2 word(s) | 3199 | 2023-04-26 14:57:29 | | | | |

| 18 | Reza Nejat | + 19 word(s) | 3218 | 2023-04-26 16:58:49 | | | | |

| 19 | Reza Nejat | -8 word(s) | 3210 | 2023-04-27 06:41:52 | | | | |

| 20 | Reza Nejat | + 15 word(s) | 3225 | 2023-04-27 06:56:07 | | | | |

| 21 | Reza Nejat | Meta information modification | 3225 | 2023-05-15 23:16:18 | | | | |

| 22 | Reza Nejat | + 28 word(s) | 3253 | 2023-05-16 10:18:38 | | | | |

| 23 | Reza Nejat | Meta information modification | 3253 | 2023-05-16 10:20:32 | | | | |

| 24 | Reza Nejat | + 21 word(s) | 3274 | 2023-05-16 23:40:31 | | |

Video Upload Options

Angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE2), a type I transmembrane mono-carboxypeptidase of renin angiotensin system (RAS), in involved in conversion of angiotensin I (Ang I) and angiotensin II (Ang II) to angiotensin (1-9) and angiotensin (1-7), respectively. This enzyme, as the receptor of SARS-CoV-2, plays a crucial role in the virus entrance into the host cells. The docking of the S protein to this receptor, eventually leads to the fusion of the virus membrane with the host cell plasma membrane to release the viral genome into the cell cytoplasm.

1. S Protein Structure

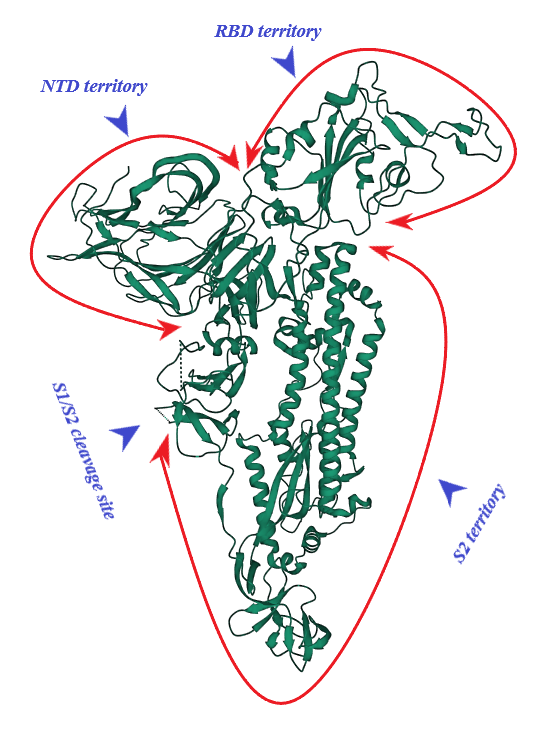

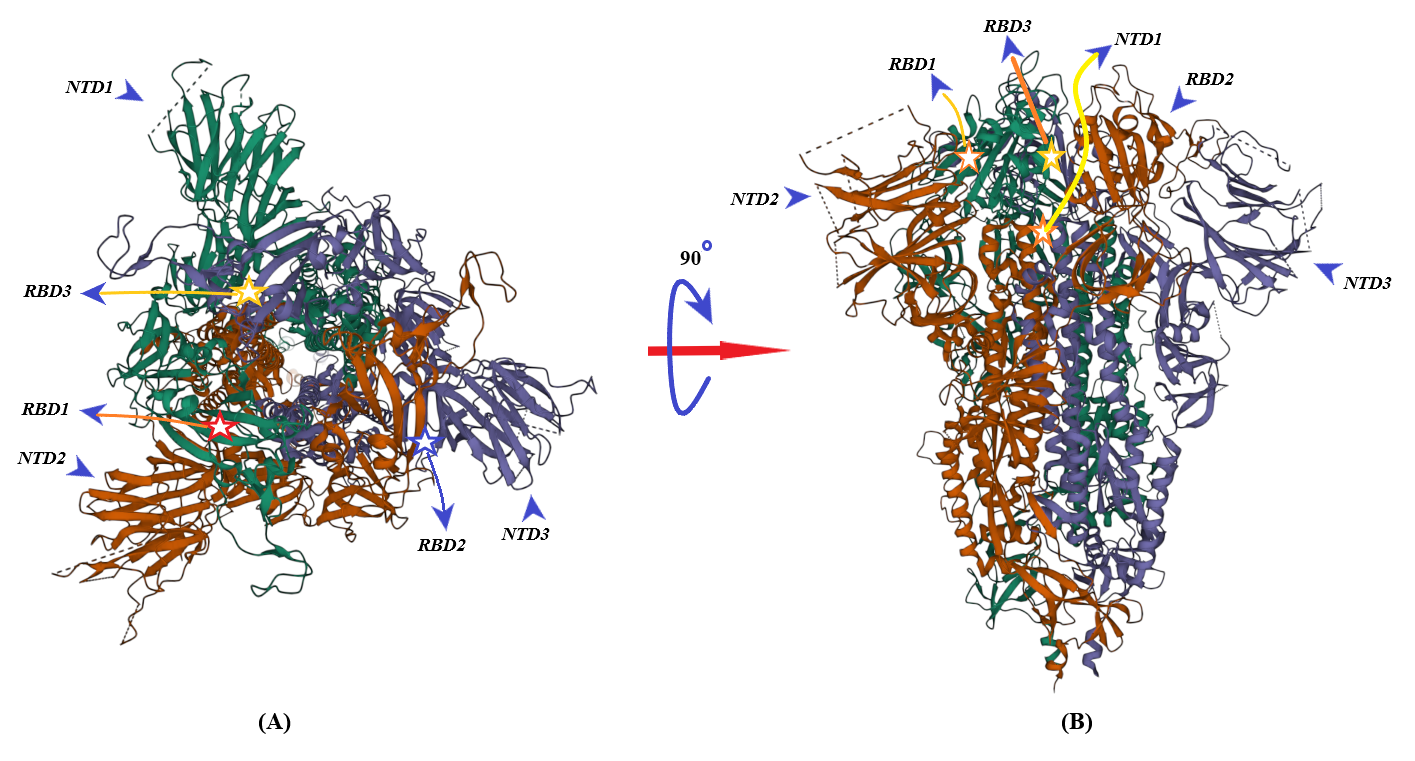

S protein of SARS-CoV-2 (of 1273 amino acid residues), a class I fusion and homo-trimeric glycoprotein, is composed of two subunits, S1 and S2, in each of its monomers. The former is in charge of docking of the virion to ACE2 and the latter promotes fusion of viral and host cell lipid outer membranes through a fusogenic process [1]. From N- toward C-terminal ends, S1 comprises a signaling sequence, an N-terminal domain (NTD), a receptor binding domain (RBD) including its receptor binding motif (RBM) and two subdomains (SD1 and SD2) [2][3]. S2, a rather conserved molecule in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, consists of a fusion peptide (FP), the heptad repeat 1 (HR1), the heptad repeat 2 (HR2), a transmembrane domain (TM) and a cytoplasmic tail (CT) [1][4]. Absent in SARS-CoV, a polybasic amino acid sequence, RRAR (Arg-Arg-Ala-Arg), called the furin-cleavage site is located at the S1/S2 boundary, the deletion of which attenuates SARS-CoV-2 replication in the respiratory cells [5] (Figure 1). It has been shown that the presence of the RRAR motif enables SARS-CoV-2 to evade endosomal interferon-induced transmembrane (IFITM) proteins [6].

Figure 1. S protein (monomer). PDB (RCSB.org) ID: 7QUS [7]. NTD: N-terminal Domain, RBD: Receptor Binding Domain

2. Binding of ACE2 with RBD Increases the Chance of Further Complexification of ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2

3. Membrane-Bound and Soluble ACE2

ACE2 contributes to infectivity and the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the host cells while physiologically plays a crucial role in protection of the lungs, heart and other tissues against a variety of inflammatory or hypoxia-induced insults [20][21][22][23]. The non-homogenous distribution of ACE2, yet in a limited scale compared to ACE, was shown in a wide variety of tissues with the highest expression in the small intestine, heart, testis, thyroid glands and adipose tissue; intermediate expression in the lungs, colon, liver, bladder and adrenal glands; and the lowest content in the blood, spleen, bone marrow, brain, blood vessels and muscles [24]. Beyond the genetic traits determined by loci near immune related genes such as IFNAR2 and CXCR6 [25], the distinct genetic variants of highly polymorphic Ace2 (gene located on chromosome Xp22.2 encoding for ACE2 protein [26]) in different populations have also been shown to affect the susceptibility to and severity of COVID-19 in some cohorts of patients [27][28][29][30].

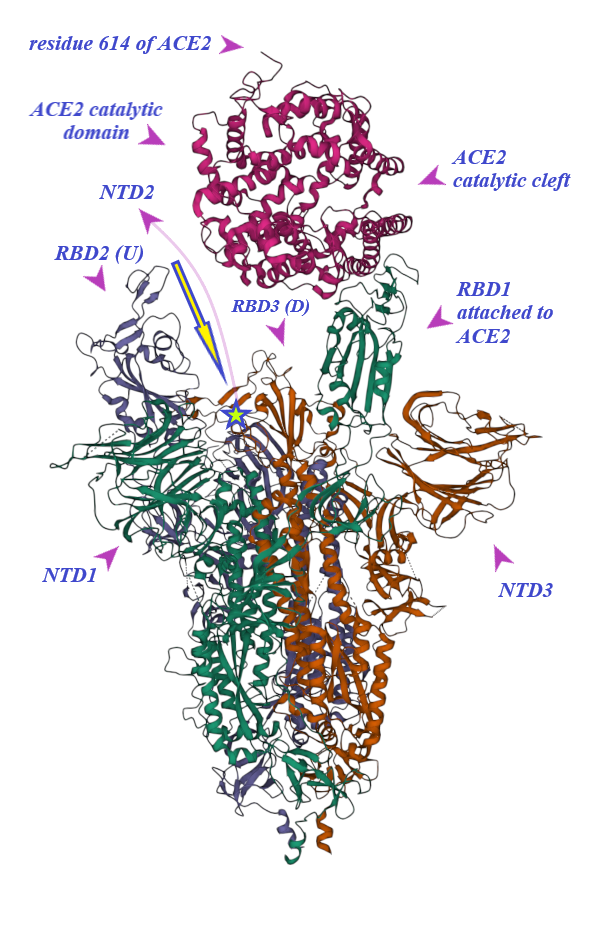

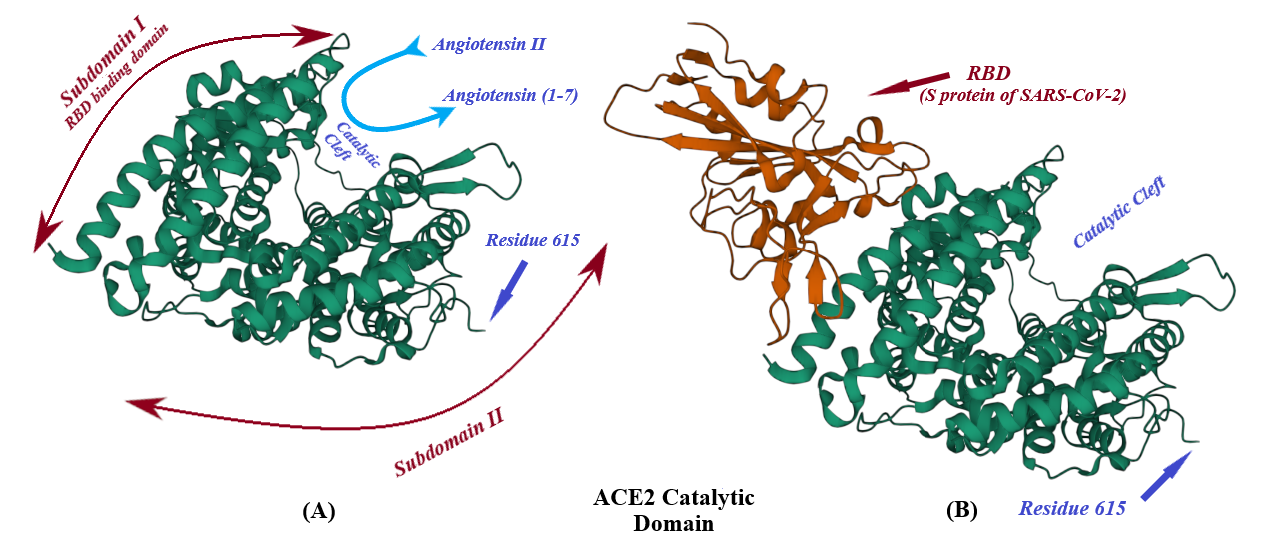

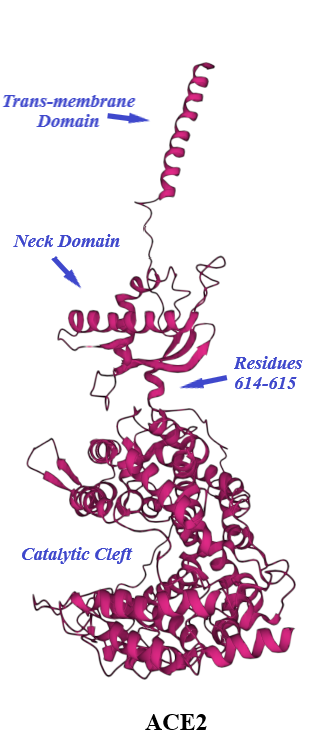

ACE2, a type I transmembrane protein of 805 residues, comprises an extracellular segment (residues 19–740) including a signal peptide of 18 amino acids, an N-terminal claw-like protease domain (PDACE2, residues 19–615) and a collectrin-like domain (residues 616–740) including ferredoxin-like fold “Neck” domain (residues 616–726) attached to a long transmembrane domain (residues 741–763) ending with a cytosolic C-terminal tail [31][32][33][34][35] (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The cytosolic tail containing a conserved endocytosis short linear motif had been demonstrated to play a role in SARS-CoV-S protein-induced shedding of ACE2, TNF-α production and SARS-CoV infection [36][37] although a combined in silico and in vitro study strengthened by confocal imaging denied any role for C-terminal tail of ACE2 in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 cell entry [38]. The collectrin-like domain contributes to dimerization of two ACE2 molecules (assuming ACE2-A and ACE2-B) through interacting with Arg652, Glu653, Ser709, Arg710 and Asp713 in ACE2-A with Tyr641, Tyr633, Asn638, Glu639, Asn636 and Arg716 in ACE2-B [31].

4. ADAM17, the Sheddase of ACE2

Regulated selective cleavage and release of the extracellular segment of many of transmembrane proteins into the extracellular space called “ectodomain shedding” modifies a diverse array of trans- and cis-signaling pathways [53]. ADAM17, the first identified shedding protease, is a Zn2+-dependent metalloproteinase and a member of the family of membrane-anchored ADAMs, which plays a role in both innate and humoral adaptive immunity, among the others [54]. This sheddase promotes proinflammatory effects through dissociating a variety of ligand proteins as its substrates including ACE2, TNF-α and transmembrane CX3CL as well as transmembrane receptors including IL6Ra and TNF receptors I and II [48][55][56][57][58]. Additionally, an animal study has revealed that ADAM17-induced degradation of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) inhibits the latter’s anti-tumorigenic and anti-osteoclastogenic properties [59].

This metalloprotease exists in two forms: the full length pro-ADAM17 of 100KDa and the mature form of 80KDa lacking the inhibitory prodomain: the latter comprises almost two thirds of its total cell content which resides predominantly in perinuclear space along with TNF-α [60][61]. ADAM17 as a type I transmembrane multidomain proteinase comprises an N-terminal signal sequence, an inhibitory prodomain, a metalloproteinase catalytic domain, a disintegrin-like domain, a cysteine-rich and membrane proximal domains (MPD, involved in substrate recognition) attached to a single transmembrane domain (TMD) ending into a cytoplasmic tail [58][62]. The TMD, but not the cytoplasmic domain, contributes to the rapid activation of this metalloprotease by different signaling pathways [63]. However, phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain of ADAM17 by mitogen activating protein kinase (MAPK) network including p38MAPK and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) as well as Polo-like kinase2 (PLK2) keep this metalloprotease proteolytically functional through prevention of its dimerization and dampening of its binding to tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase3 (TIMP3) at the cell surface [64][65]; TIMP3 plays an inhibitory role for the dimerized ADAM17 on the cell surface [66].

Given that ADAM17 small interfering RNA (siRNA) is capable of attenuating Ang II-mediated inflammation in vascular smooth muscle cells [73] it is implied that along with other downstream mediators, ADAM17 is also involved in Ang II-induced inflammatory responses. Additionally, Ang II-mediated stimulation of AT1R, a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR), provokes oxidative stress, induces phospholipase C (PLC)-mediated protein kinase C (PKC) activation and increases calcium influx [74][75][76][77]. Oxidative stress in tumor cells and platelets could previously be found to activate ADAM17 with pro-inflammatory effects (see previous paragraph) [78][79]. Reciprocally, ADAM17 in a mouse model could also increase NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) activity resulting in oxidative stress [80] which by inducing pro-inflammatory genes is intertwined with inflammation [81][82]. It is, however, noticeable that ADAM17 positively regulates Thioredoxin-1 (Trx-1) activity as the key effector of intracellular reducing system and downregulates ADAM17 as a negative feedback effect [83][84].

Furthermore, the PKC pathway, depending on the nature of its activator, affects ADAM17-dependent ectodomain shedding. Short-term (minutes) activation of protein kinase C (PKC) by phorbol ester (the strongest non-physiologic stimulator of PKC) increases ADAM17 content on the cell plasma membrane and the sheddase activity while prolonged (hours) exposure to phorbol ester downregulates mature form of ADAM17 on the cell surface abolishing the ectodomain shedding without reducing the total cell content of ADAM17 (mature plus pro-ADAM17)[85]. Conversely, ligand-activated GPCRs, such as thrombin-mediated protease activated receptor1 (PAR1), with the potential to activating of PKC signaling [86][87], induces sheddase function without any change in the content of ADAM17 on the plasma membrane [85]. Moreover, Ang II, via AT1R, was found to upregulate PAR1 and PAR2 in rat aorta which lead to pro-inflammatory responses accompanied by raising IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), the substrates of ADAM17 [61][88][89]. Along with the natural homo- and hetero-merization of GPCRs [75], an in vitro study revealed synergistic interaction between AT1R and PAR1 [90], implicating a positive influence of these receptors in activating ADAM17. Moreover, AT1R stimulation alone is associated with a rise in IL-1β which by itself promotes ectodomain shedding by ADAM17 [91][92]. Considering that Ang II via AT1R could induce PKCδ/p38MAPK [93] which also activates ADAM17 [94][95], it is logically implied that AT1R also potentiates ADAM17-induced ectodomain shedding through p38MAPK pathway. Ca2+ influx and calmodulin inhibition stimulate ADAM10 [96]. Given that ADAM17 is involved in processing of pro-α2δ-1 and α2δ-3 subunits of voltage gated calcium channels which enhances calcium influx [97] it is implied that ADAM17 also indirectly contributes to activating ADAM10 in ectodomain shedding.

5. Shedding of ACE2 Ectodomain and sACE2 in SARS-CoV-2

As was mentioned previously, ADAM10 and ADAM17, the predominant sheddases, contribute to cleaving mACE2 off the cell surface which lead to a vast array of physiological and pathological cis- and trans-signaling [55]. Cleavage of the ectodomain of mACE2 occurs through a basal low level constitutive or a metalloproteinase-dependent fashion [98]. A cell culture study showed that inhibition of both ADAM17 and ADAM10, widely found on pneumocyte type I and II, results in ACE2 increment on the surface of these cells [99]. Consistently, an animal model of diabetes proved that ADAM17 gene knockdown and overexpression could reduce and raise mACE2 shedding off the cardiomyocytes, respectively [100].

Oxidative stress, MAPK network, PKC and Ca2+ signaling activation in various viral infections including SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 has already been described [101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108]. Ang II-mediated AT1R stimulation activates these signaling pathways, as well [109][110]. All these signaling pathways directly promote ADAM17-dependent ACE2 shedding which by itself decreases angiotensin(1–7)/Ang II concentration ratio and promotes Ang II/AT1R pathway which also induces ADAM17 sheddase function (see previous section). Additionally, COVID-19 has been shown to promote ADAM17 expression both at the protein and transcriptional level [111].

In this context, neither should it be forgotten that the downregulation of mACE2 in COVID19 can be due to internalization of the virus-ACE2 complex [112][113][114][115] nor should the cleaving effects of TMPRSS2 along with ADAM17 be ignored. These two proteases compete in shedding, yet at different sites, of ACE2: ADAM17 and TMPRSS2 cleave Arginine and Lysine amino acids in residues 652–659 and 697–716, respectively [116]. However, TMPRSS2-mediated dissociation of mACE2 does not result in the release of sACE2 [117].

References

- Wang M-Y, Zhao R, Gao L-J, Gao X-F, Wang D-P, Cao J-M SARS-CoV-2: structure, biology, and structure-based therapeutics development.. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2020, 10, 587269.

- Berger I, Schaffitzel C The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: balancing stability and infectivity. Cell research 2020, 30 (12), 1059-1060.

- Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, Shan S, Zhou H, Fan S, Zhang Q, Shi X, Wang Q, Zhang L: Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581(7807), 215-220.

- Shah P, Canziani GA, Carter EP, Chaiken I The case for S2: the potential benefits of the S2 subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein as an immunogen in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 637651.

- Wu Y, Zhao S Furin cleavage sites naturally occur in coronaviruse. Stem cell research 2021, 50, 102115.

- Peacock TP, Goldhill DH, Zhou J, Baillon L, Frise R, Swann OC, Kugathasan R, Penn R, Brown JC, Sanchez-David RY: The furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is required for transmission in ferrets.. Nature microbiology 2021, 6(7), 899-909.

- Buchanan CJ, Gaunt B, Harrison PJ, Yang Y, Liu, J.; Khan, A.; Giltrap, A.M.; Le Bas, A.; Ward, P.N.; Gupta, K. Pathogen-sugar interactions revealed by universal saturation transfer analysis. Science 2022, 377, eabm3125.

- Mehdipour AR, Hummer G: Dual nature of human ACE2 glycosylation in binding to SARS-CoV-2 spike. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118(19), e2100425118.

- Zhu C, He G, Yin Q, Zeng L, Ye X, Shi Y, Xu W: Molecular biology of the SARs‐CoV‐2 spike protein: A review of current knowledge. Journal of Medical Virology 2021, 93(10), 5729-5741.

- Khare S, Azevedo M, Parajuli P, Gokulan K: Conformational changes of the receptor binding domain of sars-cov-2 spike protein and prediction of a b-cell antigenic epitope using structural data. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2021, 4, 31.

- Stalls V, Lindenberger J, Gobeil SM-C, Henderson R, Parks R, Barr M, Deyton M, Martin M, Janowska K, Huang X: Cryo-EM structures of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA. 2 spike. Cell Reports 2022, 39(13), 111009.

- Wang Y, Xu C, Wang Y, Hong Q, Zhang C, Li Z, Xu S, Zuo Q, Liu C, Huang Z: Conformational dynamics of the Beta and Kappa SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins and their complexes with ACE2 receptor revealed by cryo-EM. Nature communications 2021, 12(1), 7345.

- Yurkovetskiy L, Wang X, Pascal KE, Tomkins-Tinch C, Nyalile TP, Wang Y, Baum A, Diehl WE, Dauphin A, Carbone C: Structural and functional analysis of the D614G SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variant. Cell 2020, 183(3), 739-751. e738.

- Giron CC, Laaksonen A, Barroso da Silva FL: Up state of the SARS-COV-2 spike homotrimer favors an increased virulence for new variants. Frontiers in medical technology 2021, 3, 694347.

- Benton DJ, Wrobel AG, Xu P, Roustan C, Martin SR, Rosenthal PB, Skehel JJ, Gamblin SJ: Receptor binding and priming of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 for membrane fusion. Nature 2020, 588(7837), 327-330.

- Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, Hengartner N, Giorgi EE, Bhattacharya T, Foley B: Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell 2020, 182(4), 812-827. e819.

- Jordan M: The meaning of affinity and the importance of identity in the designed world. Interactions 2010, 17(5), 6-11.

- Delgado JM, Duro N, Rogers DM, Tkatchenko A, Pandit SA, Varma S: Molecular basis for higher affinity of SARS‐CoV‐2 spike RBD for human ACE2 receptor. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2021, 89(9), 1134-1144.

- Wu L, Zhou L, Mo M, Liu T, Wu C, Gong C, Lu K, Gong L, Zhu W, Xu Z: SARS-CoV-2 Omicron RBD shows weaker binding affinity than the currently dominant Delta variant to human ACE2. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2022, 7(1), 1-3.

- Turner, A.: . The Protective Arm of the Renin Angiotensin System (RAS): Functional Aspects and Therapeutic Implications; Unger, T., Steckelings, U.M., Eds.; Academic Press:: London, UK, 2015; pp. 185-189.

- Scialo F, Daniele A, Amato F, Pastore L, Matera MG, Cazzola M, Castaldo G, Bianco A: ACE2: the major cell entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung 2020, 198(6), 867-877.

- Kuba K, Imai Y, Ohto-Nakanishi T, Penninger JM: Trilogy of ACE2: A peptidase in the renin–angiotensin system, a SARS receptor, and a partner for amino acid transporters. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2010, 128(1), 119-128.

- Hu H, Zhang R, Dong L, Chen E, Ying K: Overexpression of ACE2 prevents hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats by inhibiting proliferation and immigration of PASMCs. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020, 24(7), 3968-3980.

- Li M-Y, Li L, Zhang Y, Wang X-S: Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. nfectious diseases of poverty 2020, 9, 23-29.

- Neimi, M.E.K.; Karjalainen, J.; Liao, R.G.; Neale, B.M.; Daly, M.; Ganna, A.; Pathak, G.A.; Andrews, S.J.; Kanai, M.; Veerapen, K.; et al.et al. Mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 600, 472-477.

- Luo Y, Liu C, Guan T, Li Y, Lai Y, Li F, Zhao H, Maimaiti T, Zeyaweiding A: Association of ACE2 genetic polymorphisms with hypertension-related target organ damages in south Xinjiang. Hypertension Research 2019, 42(5), 681-689.

- Cao Y, Li L, Feng Z, Wan S, Huang P, Sun X, Wen F, Huang X, Ning G, Wang W: in different populations. Cell discovery 2020, 6(1):1-4 Comparative genetic analysis of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2) receptor ACE2 in different populations. Cell discovery 2020, 6(1), 1-4.

- Lanjanian H, Moazzam-Jazi M, Hedayati M, Akbarzadeh M, Guity K, Sedaghati-Khayat B, Azizi F, Daneshpour MS: SARS-CoV-2 infection susceptibility influenced by ACE2 genetic polymorphisms: insights from Tehran Cardio-Metabolic Genetic Study. Scientific reports 2021, 11(1), 1-13.

- Li J, Wang Y, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Zhai Y, Dai Y, Wu Z, Nie X, Du L: Polymorphisms and mutations of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 genes are associated with COVID-19: a systematic review. European Journal of Medical Research 2022, 27(1), 1-10.

- Singh H, Choudhari R, Nema V, Khan AA: ACE2 and TMPRSS2 polymorphisms in various diseases with special reference to its impact on COVID-19 disease. Microbial pathogenesis 2021, 150, 104621.

- Senapati S, Banerjee P, Bhagavatula S, Kushwaha PP, Kumar S: Contributions of human ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in determining host–pathogen interaction of COVID-19. Journal of Genetics 2021, 100(1), 1-16.

- Devaux CA, Rolain J-M, Raoult D: ACE2 receptor polymorphism: Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2, hypertension, multi-organ failure, and COVID-19 disease outcome. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 2020, 53(3), 425-435.

- Badawi S, Ali BR: ACE2 Nascence, trafficking, and SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis: the saga continues. Badawi S, Ali BR: ACE2 Nascence, trafficking, and SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis: the saga continues. Human genomics 2021, 15(1), 1-14.

- Gheblawi M, Wang K, Viveiros A, Nguyen Q, Zhong J-C, Turner AJ, Raizada MK, Grant MB, Oudit GY: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system: celebrating the 20th anniversary of the discovery of ACE2. Circulation research 2020, 126(10), 1456-1474.

- Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, Donovan M, Woolf B, Robison K, Jeyaseelan R: A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme–related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circulation research 2000, 87(5), e1-e9.

- Haga S, Yamamoto N, Nakai-Murakami C, Osawa Y, Tokunaga K, Sata T, Yamamoto N, Sasazuki T, Ishizaka Y: Modulation of TNF-α-converting enzyme by the spike protein of SARS-CoV and ACE2 induces TNF-α production and facilitates viral entry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105(22), 7809-7814.

- Kliche J, Kuss H, Ali M, Ivarsson Y: Cytoplasmic short linear motifs in ACE2 and integrin β3 link SARS-CoV-2 host cell receptors to mediators of endocytosis and autophagy. Science signaling 2021, 14(665), eabf1117.

- Karthika T, Joseph J, Das V, Nair N, Charulekha P, Roji MD, Raj VS: SARS-CoV-2 Cellular Entry Is Independent of the ACE2 Cytoplasmic Domain Signaling. Cells 2021, 10(7), 1814.

- Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q: Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020, 367(6485), 1444-1448.

- Vickers C, Hales P, Kaushik V, Dick L, Gavin J, Tang J, Godbout K, Parsons T, Baronas E, Hsieh F: Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277(17), 14838-14843.

- Towler P, Staker B, Prasad SG, Menon S, Tang J, Parsons T, Ryan D, Fisher M, Williams D, Dales NA: ACE2 X-ray structures reveal a large hinge-bending motion important for inhibitor binding and catalysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279(17), 17996-18007.

- Villalobos LA, Hipólito-Luengo S, Ramos-González M, Cercas E, Vallejo S, Romero A, Romacho T, Carraro R, Sánchez-Ferrer CF, Peiró C: The angiotensin-(1-7)/mas axis counteracts angiotensin II-dependent and-independent pro-inflammatory signaling in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2016, 7, 482.

- Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, da Costa J, Zhang L, Pei Y: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature 2002, 417(6891), 822-828..

- Zhang J, Ney PA: Role of BNIP3 and NIX in cell death, autophagy, and mitophagy. Cell Death & Differentiation 2009, 16(7), 939-946.

- Koka V, Huang XR, Chung AC, Wang W, Truong LD, Lan HY: Angiotensin II up-regulates angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE), but down-regulates ACE2 via the AT1-ERK/p38 MAP kinase pathway. The American journal of pathology 2008, 172(5), 1174-1183.

- Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA: MAP kinase/phosphatase pathway mediates the regulation of ACE2 by angiotensin peptides. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2008, 295(5), C1169-C1174.

- Kumar SA, Wei H: Comparative docking studies to understand the binding affinity of nicotine with soluble ACE2 (sACE2)-SARS-CoV-2 complex over sACE2. Toxicology reports 2020, 7, 1366-1372.

- Eguchi S, Kawai T, Scalia R, Rizzo V: Understanding angiotensin II type 1 receptor signaling in vascular pathophysiology. Hypertension 2018, 71(5), 804-810.

- Patel VB, Clarke N, Wang Z, Fan D, Parajuli N, Basu R, Putko B, Kassiri Z, Turner AJ, Oudit GY: Angiotensin II induced proteolytic cleavage of myocardial ACE2 is mediated by TACE/ADAM-17: a positive feedback mechanism in the RAS. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 2014, 66, 167-176.

- Ortiz-Pérez JT, Riera M, Bosch X, De Caralt TM, Perea RJ, Pascual J, Soler MJ: Role of circulating angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction: a prospective controlled study. PLoS One 2013, 8(4), e61695.

- Ferder L, Inserra F, Martínez-Maldonado M: Inflammation and the metabolic syndrome: role of angiotensin II and oxidative stress. Current hypertension reports 2006, 8(3), 191-198.

- Chu KY, Leung PS: Angiotensin II in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Current Protein and Peptide Science 2009, 10(1), 75-84.

- Hayashida K, Bartlett AH, Chen Y, Park PW: Molecular and cellular mechanisms of ectodomain shedding. The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology 2010, 293(6), 925-937.

- Marczynska J, Ozga A, Wlodarczyk A, Majchrzak-Gorecka M, Kulig P, Banas M, Michalczyk-Wetula D, Majewski P, Hutloff A, Schwarz J: The role of metalloproteinase ADAM17 in regulating ICOS Ligand–mediated humoral immune responses. The Journal of Immunology 2014, 193(6), 2753-2763.

- Dreymueller D, Pruessmeyer J, Groth E, Ludwig A: The role of ADAM-mediated shedding in vascular biology. European journal of cell biology 2012, 91(6-7), 472-485.

- Grötzinger J, Lorenzen I, Düsterhöft S: Molecular insights into the multilayered regulation of ADAM17: The role of the extracellular region. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research 2017, 1864(11), 2088-2095.

- Scheller J, Chalaris A, Garbers C, Rose-John S: ADAM17: a molecular switch to control inflammation and tissue regeneration. Trends in immunology 2011, 32(8), 380-387.

- Zunke F, Rose-John S The shedding protease ADAM17: Physiology and pathophysiology. BBA - Molecular Cell Research 2017, 1864, 2059-2070.

- Kanzaki H, Shinohara F, Suzuki M, Wada S, Miyamoto Y, Yamaguchi Y, Katsumata Y, Makihira S, Kawai T, Taubman MA . A-Disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) 17 enzymatically degrades interferon-gamma. Scientific reports 2016, 6(1), 32259.

- SCHLÖNDORFF J, BECHERER JD, BLOBEL CP: Intracellular maturation and localization of the tumour necrosis factor α convertase (TACE). Biochemical Journal 2000, 347(1), 131-138.

- De Queiroz TM, Lakkappa N, Lazartigues E: ADAM17-mediated shedding of inflammatory cytokines in hypertension. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11, 1154.

- Lorenzen I, Lokau J, Düsterhöft S, Trad A, Garbers C, Scheller J, Rose-John S, Grötzinger J: The membrane-proximal domain of A Disintegrin and Metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17) is responsible for recognition of the interleukin-6 receptor and interleukin-1 receptor II. FEBS letters 2012, 586(8), 1093-1100.

- Weskamp G, Tüshaus J, Li D, Feederle R, Maretzky T, Swendemann S, Falck-Pedersen E, McIlwain DR, Mak TW, Salmon JE: ADAM17 stabilizes its interacting partner inactive Rhomboid 2 (iRhom2) but not inactive Rhomboid 1 (iRhom1). Journal of Biological Chemistry 2020, 295(13), 4350-4358.

- Al-Salihi MA, Lang PA: iRhom2: an emerging adaptor regulating immunity and disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21(18), 6570.

- Saad MI, Alhayyani S, McLeod L, Yu L, Alanazi M, Deswaerte V, Tang K, Jarde T, Smith JA, Prodanovic Z: ADAM 17 selectively activates the IL‐6 trans‐signaling/ERK MAPK axis in KRAS‐addicted lung cancer. EMBO molecular medicine 2019, 11(4), e9976.

- Fan D, Kassiri Z: Biology of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3), and its therapeutic implications in cardiovascular pathology. Frontiers in Physiology 2020, 11, 661.

- Luo W-W, Li S, Li C, Zheng Z-Q, Cao P, Tong Z, Lian H, Wang S-Y, Shu H-B, Wang Y-Y: iRhom2 is essential for innate immunity to RNA virus by antagonizing ER-and mitochondria-associated degradation of VISA. PLoS pathogens 2017, 13(11), e1006693.

- Adrain C, Zettl M, Christova Y, Taylor N, Freeman M: Tumor necrosis factor signaling requires iRhom2 to promote trafficking and activation of TACE. Science 2012, 335(6065), 225-228.

- Chao-Chu J, Murtough S, Zaman N, Pennington DJ, Blaydon DC, Kelsell DP: iRHOM2: A Regulator of Palmoplantar Biology, Inflammation, and Viral Susceptibility. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2021, 141(4), 722-726.

- Substrate-selective protein ectodomain shedding by ADAM17 and iRhom2 depends on their juxtamembrane and transmembrane domains. FASEB journal: Tang B, Li X, Maretzky T, Perez-Aguilar JM, McIlwain D, Xie Y, Zheng Y, Mak TW, Weinstein H, Blobel CP. Faseb Journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 202o, 34(4), 4956.

- Yoda M, Kimura T, Tohmonda T, Morioka H, Matsumoto M, Okada Y, Toyama Y, Horiuchi K: Systemic overexpression of TNFα-converting enzyme does not lead to enhanced shedding activity in vivo. PloS one 2013, 8(1), e54412.

- Le Gall SM, Maretzky T, Issuree PD, Niu X-D, Reiss K, Saftig P, Khokha R, Lundell D, Blobel CP: ADAM17 is regulated by a rapid and reversible mechanism that controls access to its catalytic site. Journal of cell science 2010, 123(22), 3913-3922.

- Zeng S-y, Yang L, Hong C-l, Lu H-q, Yan Q-j, Chen Y, Qin X-p: Evidence That ADAM17 Mediates the Protective Action of CGRP against Angiotensin II-Induced Inflammation in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Mediators of Inflammation 2018, 2018, 2109352.

- Guo DF, Sun YL, Hamet P, Inagami T: The angiotensin II type 1 receptor and receptor-associated proteins. Cell research 2001, 11(3), 165-180.

- Nejat R, Sadr AS, Torshizi MF, Najafi DJ: GPCRs of Diverse Physiologic and Pathologic Effects with Fingerprints in COVID-19. Biology and Life Sciences Forum 2021, 7(1), 19.

- Fuller AJ, Hauschild BC, Gonzalez-Villalobos R, Awayda MS, Imig JD, Inscho EW, Navar LG: Calcium and chloride channel activation by angiotensin II-AT1 receptors in preglomerular vascular smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2005, 289(4), F760-F767.

- Vivar R, Soto C, Copaja M, Mateluna F, Aranguiz P, Munoz JP, Chiong M, Garcia L, Letelier A, Thomas WG: Phospholipase C/protein kinase C pathway mediates angiotensin II-dependent apoptosis in neonatal rat cardiac fibroblasts expressing AT1 receptor. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology 2008, 52(2), 184-190.

- Fischer OM, Hart S, Gschwind A, Prenzel N, Ullrich A: Oxidative and osmotic stress signaling in tumor cells is mediated by ADAM proteases and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor. Molecular and cellular biology 2004, 24(12), 5172-5183.

- Brill A, Chauhan AK, Canault M, Walsh MT, Bergmeier W, Wagner DD: Oxidative stress activates ADAM17/TACE and induces its target receptor shedding in platelets in a p38-dependent fashion. Cardiovascular research 2009, 2009, 84(1), 137-144.

- Ford BM, Eid AA, Göőz M, Barnes JL, Gorin YC, Abboud HE: ADAM17 mediates Nox4 expression and NADPH oxidase activity in the kidney cortex of OVE26 mice. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2013, 305(3), F323-F332.

- Chatterjee, S. Oxidative stress and biomaterials; Dziubla, T; Butterfield, D.Allan, Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, 2016; pp. 35-58.

- Forcados GE, Muhammad A, Oladipo OO, Makama S, Meseko CA: Metabolic implications of oxidative stress and inflammatory process in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis: therapeutic potential of natural antioxidants. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2021, 11, 654813.

- e Costa RA, Granato DC, Trino LD, Yokoo S, Carnielli CM, Kawahara R, Domingues RR, Pauletti BA, Neves LX, Santana AG: ADAM17 cytoplasmic domain modulates Thioredoxin-1 conformation and activity. Redox biology 2020, 37, 101735.

- Granato DC, e Costa RA, Kawahara R, Yokoo S, Aragao AZ, Domingues RR, Pauletti BA, Honorato RV, Fattori J, Figueira ACM: Thioredoxin-1 negatively modulates ADAM17 activity through direct binding and indirect reductive activity. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2018, 29(8), 717-734.

- Lorenzen I, Lokau J, Korpys Y, Oldefest M, Flynn CM, Künzel U, Garbers C, Freeman M, Grötzinger J, Düsterhöft S: Control of ADAM17 activity by regulation of its cellular localisation. Scientific reports 2016, 6(1), 1-15.

- Fang Q, Liu X, Abe S, Kobayashi T, Wang X, Kohyama T, Hashimoto M, Wyatt T, Rennard S: Fang, Q; Liu, X; Abe, S; Kobayashi, T; Wang, X; Kohyama, T; Hashimoto, M; Wyatt, T; Rennard, S: Thrombin induces collagen gel contraction partially through PAR1 activation and PKC-ϵ. European Respiratory Journal 2004, 24(6), 918-924.

- Yang C-C, Hsiao L-D, Shih Y-F, Hsu C-K, Hu C-Y, Yang C-M: Thrombin Induces COX-2 and PGE2 Expression via PAR1/PKCalpha/MAPK-Dependent NF-kappaB Activation in Human Tracheal Smooth Muscle Cells. Mediators of Inflammation 2022, 2022, 4600029.

- He R-Q, Tang X-F, Zhang B-L, Li X-D, Hong M-N, Chen Q-Z, Han W-Q, Gao P-J: Protease-activated receptor 1 and 2 contribute to angiotensin II-induced activation of adventitial fibroblasts from rat aorta. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2016, 473(2), 517-523.

- Menghini R, Fiorentino L, Casagrande V, Lauro R, Federici M: The role of ADAM17 in metabolic inflammation. Atherosclerosis 2013, 228(1), 12-17.

- Zamel IA, Palakkott A, Ashraf A, Iratni R, Ayoub MA: Interplay between angiotensin II type 1 receptor and thrombin receptor revealed by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer assay. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11, 1283.

- Hall KC, Blobel CP: Interleukin-1 stimulates ADAM17 through a mechanism independent of its cytoplasmic domain or phosphorylation at threonine 735. PloS one 2012, 7(2), e31600.

- Pearl MH, Grotts J, Rossetti M, Zhang Q, Gjertson DW, Weng P, Elashoff D, Reed EF, Chambers ET: Cytokine profiles associated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor antibodies. Kidney international reports 2019, 4(4), 541-550.

- Cardoso VG, Gonçalves GL, Costa-Pessoa JM, Thieme K, Lins BB, Casare FAM, de Ponte MC, Camara NOS, Oliveira-Souza M: Angiotensin II-induced podocyte apoptosis is mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress/PKC-δ/p38 MAPK pathway activation and trough increased Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 activity. BMC nephrology 2018, 19(1), 1-12.

- Zhu G, Liu J, Wang Y, Jia N, Wang W, Zhang J, Liang Y, Tian H, Zhang J: ADAM17 Mediates Hypoxia-Induced Keratinocyte Migration via the p38/MAPK Pathway. BioMed research international 2021, 2021, 8328216.

- Xu P, Derynck R: Direct activation of TACE-mediated ectodomain shedding by p38 MAP kinase regulates EGF receptor-dependent cell proliferation. Molecular cell 2010, 37(4), 551-566.

- Horiuchi K, Le Gall S, Schulte M, Yamaguchi T, Reiss K, Murphy G, Toyama Y, Hartmann D, Saftig P, Blobel CP: Substrate selectivity of epidermal growth factor-receptor ligand sheddases and their regulation by phorbol esters and calcium influx. Molecular biology of the cell 2007, 18(1), 176-188.

- Kadurin I, Dahimene S, Page KM, Ellaway JI, Chaggar K, Troeberg L, Nagase H, Dolphin AC: ADAM17 mediates proteolytic maturation of voltage-gated calcium channel auxiliary α2δ subunits, and enables calcium current enhancement. Function 2022, 3(3), zqac013.

- Lambert DW, Yarski M, Warner FJ, Thornhill P, Parkin ET, Smith AI, Hooper NM, Turner AJ: Tumor necrosis factor-α convertase (ADAM17) mediates regulated ectodomain shedding of the severe-acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2). Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280(34), 30113-30119.

- Jocher G, Grass V, Tschirner SK, Riepler L, Breimann S, Kaya T, Oelsner M, Hamad MS, Hofmann LI, Blobel CP: ADAM10 and ADAM17 promote SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry and spike protein‐mediated lung cell fusion. EMBO reports 2022, 23(6), e54305.

- Cheng J, Xue F, Cheng C, Sui W, Zhang M, Qiao L, Ma J, Ji X, Chen W, Yu X: ADAM17 knockdown mitigates while ADAM17 overexpression aggravates cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction via regulating ACE2 shedding and myofibroblast transformation. Frontiers in pharmacology 2022, 13, 997916.

- Kumar R, Khandelwal N, Thachamvally R, Tripathi BN, Barua S, Kashyap SK, Maherchandani S, Kumar N: Role of MAPK/MNK1 signaling in virus replication. Virus research 2018, 253, 48-61.

- Pleschka S: RNA viruses and the mitogenic Raf/MEK/ERK signal transduction cascade. Biological Chemistry 2008, 389(10), 1273-1282.

- Huang C, Feng F, Shi Y, Li W, Wang Z, Zhu Y, Yuan S, Hu D, Dai J, Jiang Q: Protein Kinase C Inhibitors Reduce SARS-CoV-2 Replication in Cultured Cells. Microbiology spectrum 2022, 10(5), e01056-01022.

- Liu M, Yang Y, Gu C, Yue Y, Wu KK, Wu J, Zhu Y: Spike protein of SARS‐CoV stimulates cyclooxygenase‐2 expression via both calcium‐dependent and calcium‐independent protein kinase C pathways. The FASEB Journal 2007, 21(7), 1586-1596.

- Wieczfinska J, Kleniewska P, Pawliczak R: Oxidative stress-related mechanisms in SARS-CoV-2 infections. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2022, 2022, 5589089.

- Suhail S, Zajac J, Fossum C, Lowater H, McCracken C, Severson N, Laatsch B, Narkiewicz-Jodko A, Johnson B, Liebau J: Role of oxidative stress on SARS-CoV (SARS) and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection: a review. The protein journal 2020, 39(6), 644-656.

- Berlansky S, Sallinger M, Grabmayr H, Humer C, Bernhard A, Fahrner M, Frischauf I: Calcium signals during SARS-CoV-2 infection: assessing the potential of emerging therapies. Cells 2022, 11(2):253 2022, 11(2), 253.

- Vollbracht C, Kraft K: Oxidative Stress and Hyper-Inflammation as Major Drivers of Severe COVID-19 and Long COVID: Implications for the Benefit of High-Dose Intravenous Vitamin C. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 899198.

- Aiello E, Cingolani H: Angiotensin II stimulates cardiac L-type Ca2+ current by a Ca2+-and protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2001, 280(4), H1528-H1536.

- Verma K, Pant M, Paliwal S, Dwivedi J, Sharma S: An Insight on Multicentric Signaling of Angiotensin II in Cardiovascular system: A Recent Update. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 734917.

- Palacios Y, Ruiz A, Ramon-Luing LA, Ocaña-Guzman R, Barreto-Rodriguez O, Sanchez-Moncivais A, Tecuatzi-Cadena B, Regalado-García AG, Pineda-Gudiño RD, García-Martínez A: Severe COVID-19 patients show an increase in soluble TNFR1 and ADAM17, with a relationship to mortality. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22(16), 8423.

- Vieira C, Nery L, Martins L, Jabour L, Dias R, Simões e Silva AC: Downregulation of membrane-bound angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor has a pivotal role in COVID-19 immunopathology. Current Drug Targets 2021, 22(3), 254-281.

- Ramos SG, da Cruz Rattis BA, Ottaviani G, Celes MRN, Dias EP: ACE2 down-regulation may act as a transient molecular disease causing RAAS dysregulation and tissue damage in the microcirculatory environment among COVID-19 patients. The American journal of pathology 2021, 191(7), 1154-1164.

- Yalcin HC, Sukumaran V, Al-Ruweidi MKA, Shurbaji S: Do changes in ace-2 expression affect SARS-CoV-2 virulence and related complications: A closer look into membrane-bound and soluble forms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(13), 6703.

- Tseng YH, Yang RC, Lu TS: Two hits to the renin‐angiotensin system may play a key role in severe COVID‐19. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences 2020, 36(6), 389-392.

- Heurich A, Hofmann-Winkler H, Gierer S, Liepold T, Jahn O, Pöhlmann S: TMPRSS2 and ADAM17 cleave ACE2 differentially and only proteolysis by TMPRSS2 augments entry driven by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. Journal of virology 2014, 88(2), 1293-1307.

- Zipeto D, Palmeira JdF, Argañaraz GA, Argañaraz ER: ACE2/ADAM17/TMPRSS2 interplay may be the main risk factor for COVID-19. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 2642.

- Tang Q, Wang Y, Ou L, Li J, Zheng K, Zhan H, Gu J, Zhou G, Xie S, Zhang J: Downregulation of ACE2 expression by SARS-CoV-2 worsens the prognosis of KIRC and KIRP patients via metabolism and immunoregulation. International journal of biological sciences 2021, 17(8), 1925.

- Bourgonje AR, Abdulle AE, Timens W, Hillebrands JL, Navis GJ, Gordijn SJ, Bolling MC, Dijkstra G, Voors AA, Osterhaus AD: Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS‐CoV‐2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). The Journal of pathology 2020, 251(3), 228-248.

- Haga S, Nagata N, Okamura T, Yamamoto N, Sata T, Yamamoto N, Sasazuki T, Ishizaka Y: TACE antagonists blocking ACE2 shedding caused by the spike protein of SARS-CoV are candidate antiviral compounds. Antiviral research 2010, 85(3), 551-555.

- Harte JV, Wakerlin SL, Lindsay AJ, McCarthy JV, Coleman-Vaughan C: Metalloprotease-Dependent S2′-Activation Promotes Cell–Cell Fusion and Syncytiation of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2022, 14(10), 2094.

- Kornilov SA, Lucas I, Jade K, Dai CL, Lovejoy JC, Magis AT: Plasma levels of soluble ACE2are associated with sex, Metabolic Syndrome, and its biomarkers in a large cohort, pointing to a possible mechanism for increased severity in COVID-19. Critical care 2020, 24(1), 1-3.

- Mariappan V, Ranganadin P, Shanmugam L, Rao S, Pillai AB: Early shedding of membrane-bounded ACE2 could be an indicator for disease severity in SARS-CoV-2. Biochimie 2022, 201, 139-147.

- Jia HP, Look DC, Tan P, Shi L, Hickey M, Gakhar L, Chappell MC, Wohlford-Lenane C, McCray Jr PB: Ectodomain shedding of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in human airway epithelia. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2009, 297(1), L84-L96.

- Wang J, Zhao H, An Y: ACE2 Shedding and the Role in COVID-19. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2022, 11, 789180.

- Rodriguez-Perez AI, Labandeira CM, Pedrosa MA, Valenzuela R, Suarez-Quintanilla JA, Cortes-Ayaso M, Mayán-Conesa P, Labandeira-Garcia JL Autoantibodies against ACE2 and angiotensin type-1 receptors increase severity of COVID-19. Journal of Autoimmunity 2021, 122, 102683.

- Arthur JM, Forrest JC, Boehme KW, Kennedy JL, Owens S, Herzog C, Liu J, Harville TO Development of ACE2 autoantibodies after SARS-CoV-2 infection. PloS one 2021, 16(9), e0257016..