Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alessia Ruggiero | -- | 2555 | 2023-02-06 14:17:10 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | + 1 word(s) | 2556 | 2023-02-07 06:31:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Romano, M.; Squeglia, F.; Kramarska, E.; Barra, G.; Choi, H.; Kim, H.; Ruggiero, A.; Berisio, R. Immune Response to Tuberculosis Infection: A Structural Overview. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40886 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Romano M, Squeglia F, Kramarska E, Barra G, Choi H, Kim H, et al. Immune Response to Tuberculosis Infection: A Structural Overview. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40886. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Romano, Maria, Flavia Squeglia, Eliza Kramarska, Giovanni Barra, Han-Gyu Choi, Hwa-Jung Kim, Alessia Ruggiero, Rita Berisio. "Immune Response to Tuberculosis Infection: A Structural Overview" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40886 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Romano, M., Squeglia, F., Kramarska, E., Barra, G., Choi, H., Kim, H., Ruggiero, A., & Berisio, R. (2023, February 06). Immune Response to Tuberculosis Infection: A Structural Overview. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40886

Romano, Maria, et al. "Immune Response to Tuberculosis Infection: A Structural Overview." Encyclopedia. Web. 06 February, 2023.

Copy Citation

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading global cause of death from an infectious bacterial agent. Limiting tuberculosis epidemic spread is an urgent global public health priority. The larger availability of antigen structural information as well as a better understanding of the complex host immune response to TB infection is a strong premise for a further acceleration of TB vaccine development. The contribution of Structural Vaccinology (SV) to the development of safer and effective antigens is discussed herein.

tuberculosis

vaccine

protein

structure

immune response

1. Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the etiological agent of Tuberculosis, is still one of the most life-threatening pathogens. In 2021, Mtb infected 10.6 million people and killed 1.6 million, with cases of multidrug-resistant TB having risen to 450,000 globally [1]. Tuberculosis (TB) is airborne-transmitted and mainly affects the lungs, although it can also affect other districts. Following the exposure to Mtb, 5–10% of infected individuals develop active TB disease within the first five years. In the remaining 90%, the infection remains latent retaining a persistent risk of developing active TB disease throughout their lifetime [2]. Furthermore, co-infections with other pathogens, such as HIV, promote the progression to the active disease, with a 20-fold increase of the risk of latent TB reactivation [3].

The success of Mtb fully relies on its ability to survive and persist within the hostile environment of macrophages, establishing a dynamic equilibrium with host immune system [4]. This pathogen’s remarkable resilience and infectivity is largely due to its unique cell envelope, comprising of four main layers: (i) the plasma membrane or inner membrane (IM), (ii) the peptidoglycan–arabinogalactan complex (AGP), (iii) an asymmetrical outer membrane (OM) or ‘mycomembrane’, that is covalently linked to AGP via the mycolic acids, and (iv) the outermost capsule [5][6]. Modifications of this complex cell envelope have been associated to the remarkable ability of Mtb to resuscitate from its state of dormancy even after 10 years [7][8].

Despite intensive research efforts, Mtb pathogenicity mechanism is still poorly understood, and thus diagnosis and therapy for TB remain a challenge. The standard TB treatment consists of a combination of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide, followed by a combination of isoniazid and rifampicin only [9]. Therefore, preventing TB disease rather than curing the infection has been the primary target for vaccine development.

In the case of TB, the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, which was developed in 1921 with this approach, offers only a partial and variable protection in infants and has a little impact in controlling the pulmonary infection in all other age groups, as adolescents and adults [10]. In the last three decades, several strategies and a broad range of vaccine technologies have been tested to improve or replace BCG- vaccine [11].

Actually, several vaccines against TB are in the pipeline, including live attenuated whole-cell vaccines, inactivated whole-cell vaccine, adjuvanted protein subunit vaccine, and viral-vectored vaccines [12]. Among these, subunit vaccines are extremely promising candidates, as they overcome safety concerns and optimise antigen targeting. However, a comprehensive knowledge of TB-induced innate and adaptive immune responses is key to the design of effective antigens able to stimulate more types of immune mechanisms. Also, strong efforts must be dedicated to antigen re-engineering to enhance their immune-stimulating effects. Here, researchers report the current knowledge of TB induced immune responses and provide a panoramic of the current stage of TB vaccine development,

2. Immune Response to TB Infection

Mtb spreads from one person to another through tiny droplets released into the air with coughs and sneezes. The bacilli reach the pulmonary alveoli through the bronchial tree and start to infect the alveolar macrophages. Typically, within a few weeks the immune system is able to stem the infection, confining the infected macrophages to a kind of bulwark made up of aggregates of immune cells, called granuloma [13]. This peculiar formation in the lung, with infected macrophages in the center and lymphocytes, stem cells, and epithelial cells in the marginal zone, is a typical sign of primary response to Mtb infection. The natural granuloma can be killed or survive in a quiescent state for several months. While the majority of individuals exposed to Mtb are able to control infection in the form of Latent TB (LTBI), an arsenal against Mtb and other pathogens is the host immune system, which acts through the concerted actions of the innate and adaptive immunity.

2.1. Innate Immunity against Mtb

The major players of innate immunity against Mtb include airway epithelial cells (AECs), macrophages, neutrophils, natural killer cells (NKs), dendritic cells (DCs), mast cells and the complement .

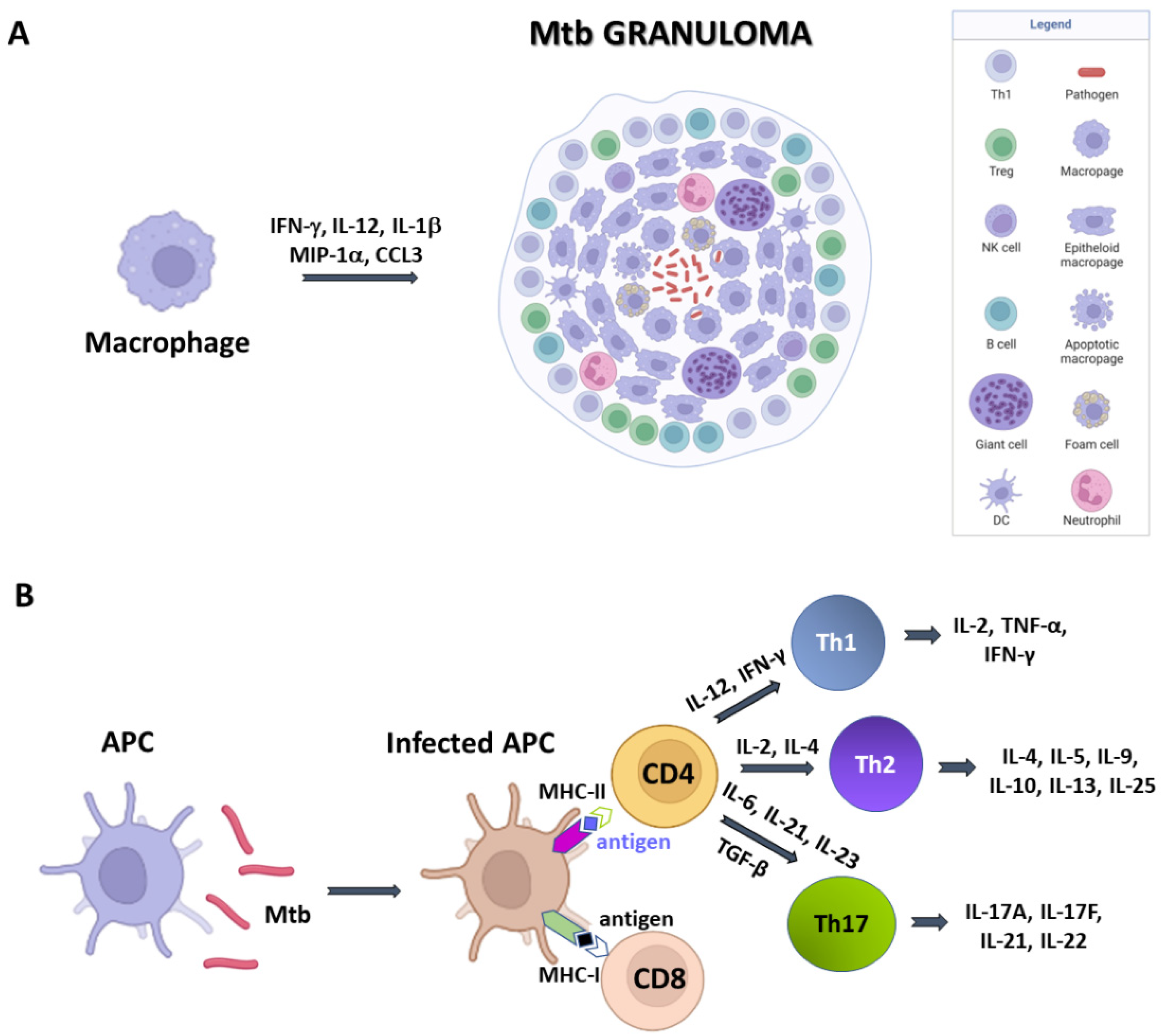

Structurally, granulomas are compact and organised aggregates, with macrophages surrounding the site of infection and other immune cells, including neutrophils, DCs, NK cells, located at their periphery (Figure 1A). Neutrophils are recruited in situ by pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines and alarmins (S100A8/A9 proteins) and play a complex role in the immunopathology due to Mtb infection [14]. Indeed, factors released by neutrophils during respiratory bursts, such as elastase, collagenase, and myeloperoxidase, indiscriminately damage both bacilli and host cells. Also, lymphocyte apoptosis can be induced by the programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expressed on the neutrophil cell membrane [15][16]. NK cells are large granular lymphocytes which recognise the target nonspecifically and without the aid of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. They cause lysis or apoptosis of target cells and, when stimulated with cytokines of the interferon class (such as IFN types α, β, and γ, IL-2 or IL-12), can increase their cytotoxic power. Activated NK cells are able to bind different components of the bacterial cell wall of Mtb, through their NKp44 receptor [17]. In addition, NK cells can recognise stress molecules overexpressed on the surface of host cells after Mtb infection. Following the recognition event, NK cells can act on Mtb through canonical cytotoxic mechanisms, such as the production of cytoplasmic granules containing perforin, granulysin and granzyme, or indirectly, stimulating and activating macrophages.

Figure 1. A simplified sketch of Mtb-induced immune reaction. (A) Macrophages produce cytokines which recruit other immune cells to form the Mtb granuloma. In these structures, macrophages can differentiate in other cell types, like epithelioid cells, giant cells, and foamy macrophages. (B) Antigen presenting cells (APCs) expose antigens on their MHC molecules, thus bringing them to T cells CD4 and CD8. Cytokine production by APCs induce T cell differentiation.

DCs are the most interesting cellular elements of the immune system because their function straddles the line between innate and adaptive immunities. Indeed, since T lymphocytes are not able to recognise directly complex protein antigens, DCs are required to process the protein antigens into smaller fragments and conjugate these antigenic peptides to MHC I or MHC II complexes. During Mtb infection, DCs bind and internalise the bacilli through the receptor DC-SIGN, (Dendritic Cell-Specific Intercellular adhesion molecule-3-Grabbing Non-integrin) also known as CD209 (Cluster of Differentiation 209) [15]. This is a C-type lectin receptor present on the surface of the DCs [18]. Once the MHC has bound the protein antigens, it is recognised by CD8 and CD4 T cells and activate an adaptive immune response. Dendritic cells also have a great capacity for cytokine production and stimulate T-cell differentiation.

2.2. Adaptive Immunity against Mtb

Mtb-infected APCs (macrophages and DCs) secrete cytokines that include IL-12, IL-23, IL-7, IL-15 and TNF-α, and present antigens to several T-cell populations, including CD4+ T cells (MHC class II pathway) and CD8+ T cells (MHC class I pathway) (Figure 1B) [19]. Activated APCs stimulate the T cell receptor (TCR) resulting in T cell proliferation. Following TCR activation by APCs, CD4+ T cells differentiate into either T helper cells (Th), which secrete diverse effector molecules contributing to cell-mediated or humoral immune responses, inflammation or immune-regulation. The importance of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is principally related to their IFN-γ production, which is particularly relevant in the early stages of Mtb infection [20].

The adaptive response mediated by T lymphocytes plays a key role in eliminating Mtb whereas a minor role is attributed to humoral or antibody-based immunity in preventing the infection. Humoral immunity, one of the two arms of the adaptive immune response, typically results in the generation of antigen-specific antibodies that target invading microbial pathogens or vaccine antigens. In the case of TB, there is emerging evidence that B cells and humoral immunity can modulate the immune response [21]. Different than humoral immunity, cell-mediated immunity involved in protective immune response to Mtb is well understood, due to the availability of animal models. In addition, within the lymph nodes, T lymphocytes undergo a process of activation and production of populations which are specific for Mtb antigens. Well-known immuno-dominant antigens recognised by T cells include Early Secretory Antigenic Target-6 (ESAT-6), Culture Filtrate Protein antigen 10-kDa (CFP-10), antigens 85A and 85B (Ag85A, Ag85B) and TB10.4. However, the identification and study of new antigens recognised by these T cells is critical for a better understanding of the immuno-biological characteristics of TB and for the development of new vaccines.

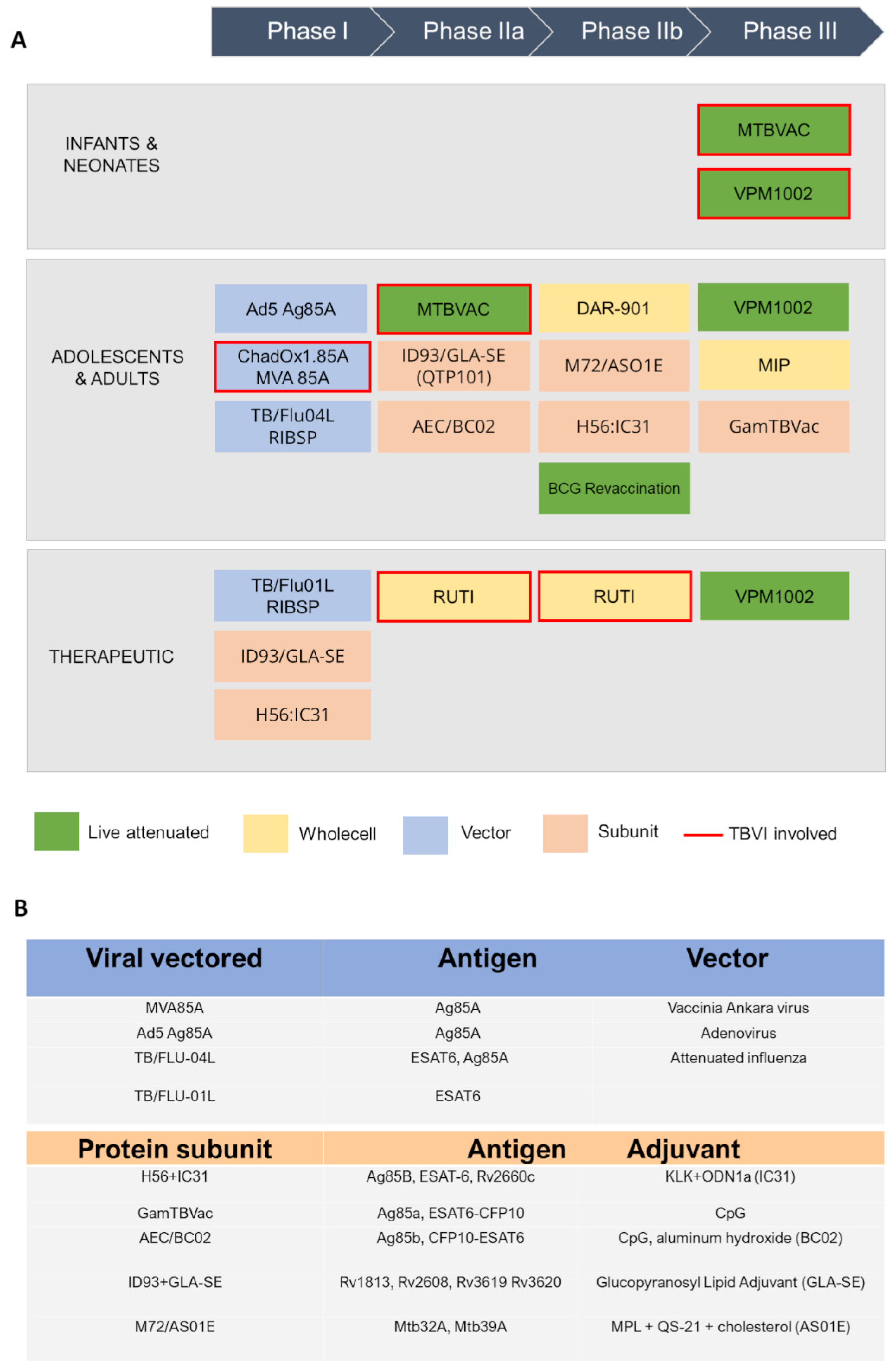

3. Vaccine Approaches against TB

Currently, the global TB vaccine portfolio includes over 16 distinct vaccine candidates at different stages of clinical development (Figure 2). These candidates fall into several categories: (i) live attenuated mycobacterial vaccine, which target either BCG- replacement at birth and/or prevention of TB in adolescents and adults, (ii) whole killed and fragmented-cell vaccines for therapeutic purposes, (iii) adjuvanted protein subunit vaccines based on one or more recombinant Mtb fusion proteins for preventive pre- and post-exposure, and (iv) viral-vectored vaccines, whose goal is to boost BCG-immunity.

Figure 2. A schematic view of TB antigens in clinical trials. (A) Summary of TB vaccine candidates currently in clinical trials, updated to October 2022 (https://www.tbvi.eu/what-we-do/pipeline-of-vaccines/, accessed on 20 October 2022). (B) specific antigens encoded in viral vectored vaccines (top) and contained in protein subunit vaccines, along with their adjuvants (bottom).

4. Structural Vaccinology as a Tool to Enhance Antigenicity of TB Subunit Vaccines

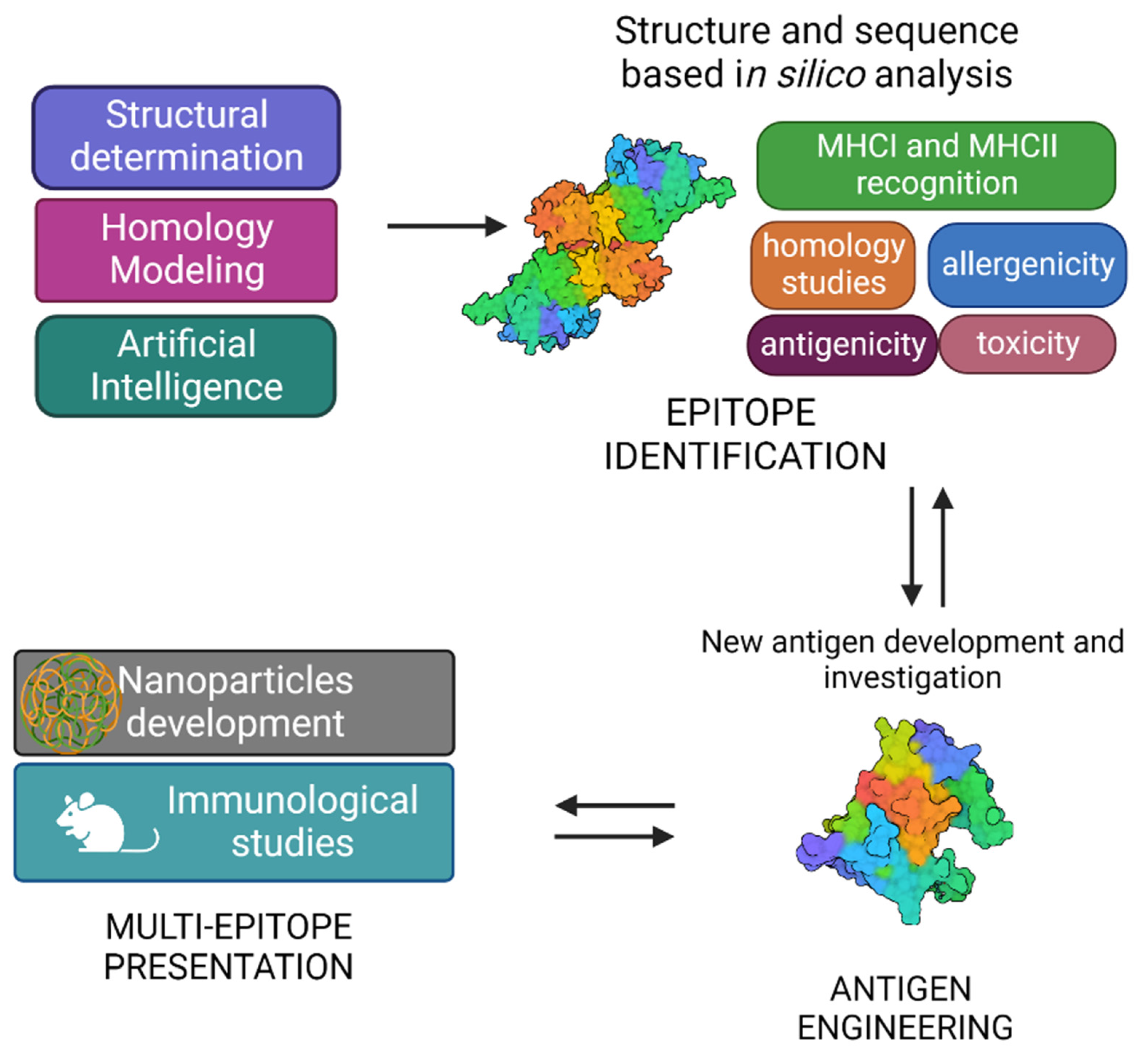

Structural vaccinology (SV) or structure-based antigen design is a rational approach that uses three-dimensional structural information to design novel and enhanced vaccine antigens. As previously mentioned, this strategy is crucial to the development of effective subunit antigens.

The typical SV approach, reported in Figure 3, involves the determination of the three-dimensional structure of the antigen or antigen–antibody complex using structural biology tools. This is achieved by combining the benefits of RV, with advancements in X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy and single particle Cryo-Electron Microscopy, and novel computational approaches, including Artificial Intelligence (AI). Experimental data on protein structures and AI predictions can be exploited and used to improve the reliability of predictions of immunogenicity, toxicity, allergenicity, using a variety of available software.

Figure 3. Graphical representation of structural vaccinology approach.

A vast number of bioinformatic tools have become available to assist the scientists in identifying the immunogenic properties of potential antigens and reducing the time of research [22]. Indeed, immunological and bioinformatic knowledge are synergistically combined with the structural insights allowing the re-design of vaccine antigens through protein engineering strategies. Finally, re-engineered antigens or epitopes are tested for their safety and efficacy in cell-based assays and in vivo. Based on the preclinical findings, the candidate vaccines can be redesigned to improve their immunogenicity and efficacy.

Structural vaccinology represents a powerful tool for the rational design or modification of vaccine antigens allowing (i) to selectively enhance antigen specific immunogenic properties, (ii) to combine more immune stimulation strategies by conjugating more antigens and (iii) to develop antigens with multi-epitope presentation [23][24][25]. The SV approach has also shown to be a useful tool to design multi-epitope vaccines against TB.

5. Novel Promising Subunit Vaccines against TB

Apart from the subunit vaccines in clinical trials, more subunit antigens are being proposed in preclinical studies, like H107 and CysVac2. Both vaccines are fusion proteins and are strongly immunogenic when are adjuvanted [26][27]. Also, several proteins have been shown to possess immunomodulatory properties and constitute a reservoir of optimum candidates for TB vaccine development. In this framework, researchers have investigated a panel of vaccine antigens exploiting diverse typologies of immune stimulations. These proteins play different roles in Mtb biology and different cell localisations. Indeed, some of them are periplasmic and involved in its complex cell wall processing, through the degradation of its peptidoglycan. Others play important role in cytosolic functions, such as ribosome recycling factors, Universal Stress Proteins (USP) etc. However, independent of their roles and cell localisation, they can stimulate Mtb innate and, in some cases, adaptive response. Researchers believe that a successful vaccine strategy must, beside using structural information for antigen improvement, combine different immune stimulation mechanisms.

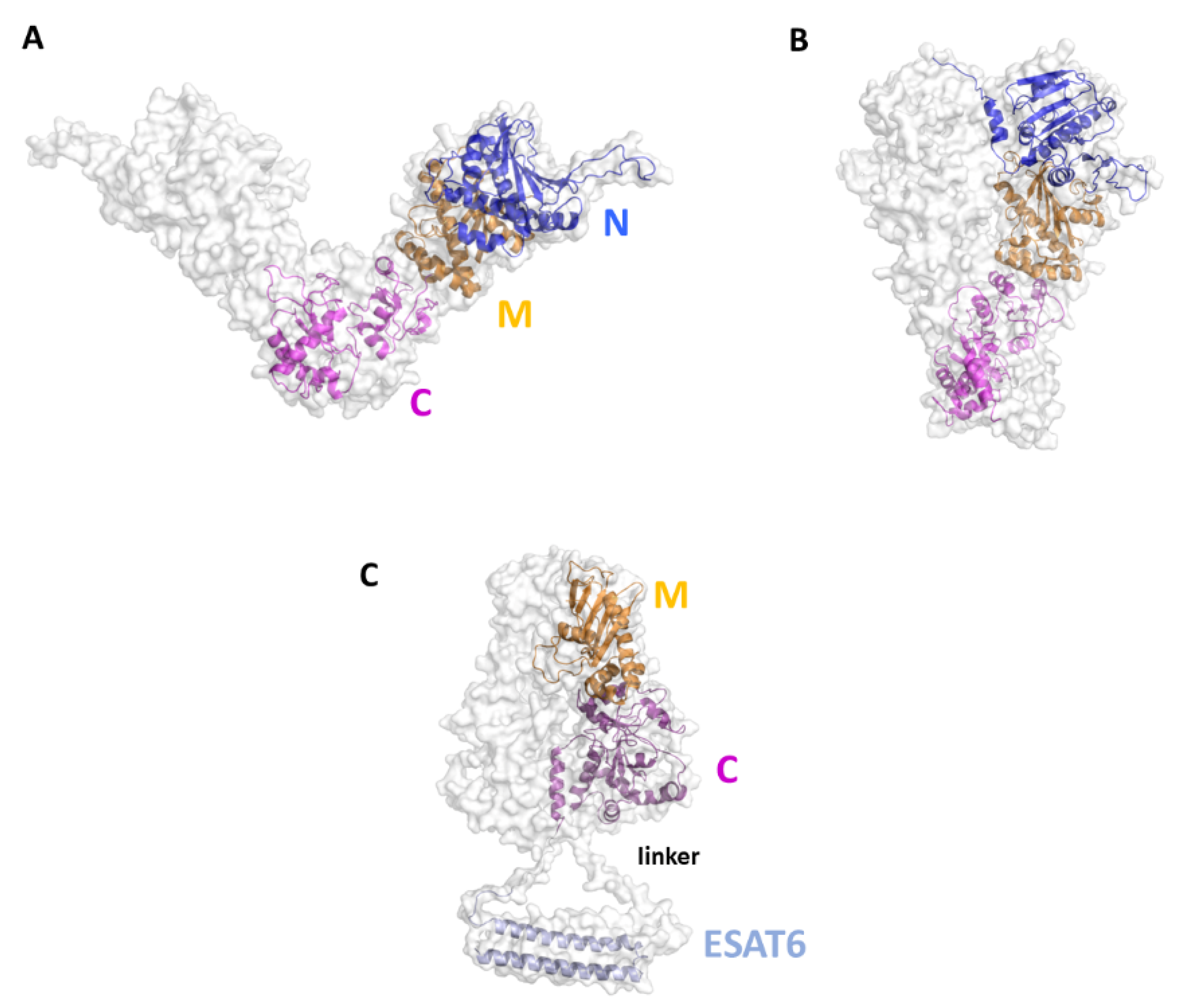

Rv2299c and ESAT6: Combining Dendritic and T Cell Stimulation

Rv2299c, also denoted also as HtpGMtb, belongs to the heat-shock protein 90 (HSP90) family and was identified as a potent DC-maturation agent [28][29]. The protein is highly conserved among Mtb strains [30], a finding that makes HtpGMtb an exceptional candidate for vaccines which target Th1 immunity. This type of response is essential in TB infection and highly depends on the early activation of DCs and their migration to the lymph nodes, where they can efficiently present antigens and stimulate proliferation of T cells [29]. Interestingly, better effects were obtained using HtpGMtb fused to ESAT-6, a well-known T cell activator. This conjugated antigen was also able of boosting effect in mice previously vaccinated with BCG [29].

Although no experimental structures of HtpGMtb are still available, computational approaches showed that HtpGMtb presents a highly stable dimeric structure, where each monomer is composed of three domains [28]. A large conformational flexibility was associated to the proposed clamping mechanism needed for the chaperon function of HtpGMtb [28][30][31] (Figure 4A, B). Using a SV approach, researchers predicted and experimentally confirmed that the most immunoreactive regions are located on the C-terminal and middle domains, whereas the N-terminal catalytic domain plays no role in elicitation of the immune response. These findings led us to design of new vaccine antigen candidates with enhanced biophysical properties and easier to produce, albeit conserved or enhanced antigenic properties [30]. Importantly, the antigen obtained upon conjugation of the C-terminal and Middle domains with ESAT6 (HtpG-MCMtb-ESAT6), Figure 4C, was more immunoreactive than the full-length HtpGMtb-ESAT6. Indeed, T cells activated by DCs matured with HtpG-MCMtb-ESAT6 induced best Mtb growth inhibition in macrophages [30].

Figure 4. Cartoon and surface representations of the HtpGMtb antigen. Homology models of the open (A) and close (B) conformations of HtpGMtb. Each chain is composed of the three domains N (residues 12–246), M (247–416) and C (417–645). (C) Model of the conjugated HtpG-MCMtb-ESAT6. A linker was inserted between the C domain and ESAT6 (sequence PNSSSVDKL, [30]). The conjugation strategy combines the DC activating property of HtpG-MCMtb with the T-cell activating property of ESAT6.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

A huge scientific advance has been made since the discovery of the BCG vaccine against TB, in 1921. Meanwhile, and however, TB has undergone phases when there were reasons to believe that it was a thing of the past. A fair analysis of literature makes it evident that a strong acceleration has characterised the last two decades, as over sixteen vaccine candidates are currently in clinical phases. Of these, five are subunit vaccine antigens. Also, there are strong reasons to believe that this acceleration will further proceed, given the huge impact of bioinformatics and structural biology on vaccine development, e.g., to enhance the immune response to subunit antigens and rationally design conjugation strategies to contemporarily exploit multiple immune responses. Researchers reckon that the combination of SV to identify immunogenic regions and conjugation strategies to induce immune modulating mechanisms are the keys to future acceleration in vaccine development. In this framework, researchers present in the above sections examples of vaccine antigens studied in the labs, which have benefited and will further benefit of SV for their improvement.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2022; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Pai, M.; Behr, M.A.; Dowdy, D.; Dheda, K.; Divangahi, M.; Boehme, C.C.; Ginsberg, A.; Swaminathan, S.; Spigelman, M.; Getahun, H.; et al. Tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16076.

- Pawlowski, A.; Jansson, M.; Sköld, M.; Rottenberg, M.E.; Källenius, G. Tuberculosis and HIV Co-Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002464.

- Gengenbacher, M.; Kaufmann, S.H.E. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Success through Dormancy. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 514–532.

- Kalscheuer, R.; Palacios, A.; Anso, I.; Cifuente, J.; Anguita, J.; Jacobs, W.R.; Guerin, M.E.; Prados-Rosales, R. The Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Capsule: A Cell Structure with Key Implications in Pathogenesis. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 1995–2016.

- Batt, S.M.; Minnikin, D.E.; Besra, G.S. The Thick Waxy Coat of Mycobacteria, a Protective Layer against Antibiotics and the Host’s Immune System. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 1983–2006.

- Squeglia, F.; Moreira, M.; Ruggiero, A.; Berisio, R. The Cell Wall Hydrolytic NlpC/P60 Endopeptidases in Mycobacterial Cytokinesis: A Structural Perspective. Cells 2019, 8, 609.

- Veatch, A.V.; Kaushal, D. Opening Pandora’s Box: Mechanisms of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Resuscitation. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 145–157.

- Suárez, I.; Fünger, S.M.; Kröger, S.; Rademacher, J.; Fätkenheuer, G.; Rybniker, J. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Tuberculosis. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 729–735.

- 100 Years of Mycobacterium Bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34506734/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Scriba, T.J.; Netea, M.G.; Ginsberg, A.M. Key Recent Advances in TB Vaccine Development and Understanding of Protective Immune Responses against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Semin. Immunol. 2020, 50, 101431.

- Kaufmann, S.H.E. The Tuberculosis Vaccine Development Pipeline: Present and Future Priorities and Challenges for Research and Innovation. In Essential Tuberculosis; Migliori, G.B., Raviglione, M.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 395–405. ISBN 978-3-030-66703-0.

- Scriba, T.J.; Coussens, A.K.; Fletcher, H.A. Human Immunology of Tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5.

- Gopal, R.; Monin, L.; Torres, D.; Slight, S.; Mehra, S.; McKenna, K.C.; Fallert Junecko, B.A.; Reinhart, T.A.; Kolls, J.; Báez-Saldaña, R.; et al. S100A8/A9 Proteins Mediate Neutrophilic Inflammation and Lung Pathology during Tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 1137–1146.

- De Martino, M.; Lodi, L.; Galli, L.; Chiappini, E. Immune Response to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: A Narrative Review. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 350.

- McNab, F.W.; Berry, M.P.R.; Graham, C.M.; Bloch, S.A.A.; Oni, T.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Kon, O.M.; Banchereau, J.; Chaussabel, D.; et al. Programmed Death Ligand 1 Is Over-Expressed by Neutrophils in the Blood of Patients with Active Tuberculosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 1941–1947.

- Sia, J.K.; Rengarajan, J. Immunology of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7.

- Abrahem, R.; Chiang, E.; Haquang, J.; Nham, A.; Ting, Y.-S.; Venketaraman, V. The Role of Dendritic Cells in TB and HIV Infection. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, E2661.

- Kaufmann, S. Protection against Tuberculosis: Cytokines, T Cells, and Macrophages. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, ii54–ii58.

- Lyadova, I.V.; Panteleev, A.V. Th1 and Th17 Cells in Tuberculosis: Protection, Pathology, and Biomarkers. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 854507.

- Kramarska, E.; Squeglia, F.; De Maio, F.; Delogu, G.; Berisio, R. PE_PGRS33, an Important Virulence Factor of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Potential Target of Host Humoral Immune Response. Cells 2021, 10, 161.

- Soria-Guerra, R.E.; Nieto-Gomez, R.; Govea-Alonso, D.O.; Rosales-Mendoza, S. An Overview of Bioinformatics Tools for Epitope Prediction: Implications on Vaccine Development. J. Biomed. Inform. 2015, 53, 405–414.

- Dormitzer, P.R.; Grandi, G.; Rappuoli, R. Structural Vaccinology Starts to Deliver. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 807–813.

- Negahdaripour, M.; Nezafat, N.; Eslami, M.; Ghoshoon, M.B.; Shoolian, E.; Najafipour, S.; Morowvat, M.H.; Dehshahri, A.; Erfani, N.; Ghasemi, Y. Structural Vaccinology Considerations for in Silico Designing of a Multi-Epitope Vaccine. Infection. Genet. Evol. 2018, 58, 96–109.

- Soltan, M.A.; Magdy, D.; Solyman, S.M.; Hanora, A. Design of Staphylococcus Aureus New Vaccine Candidates with B and T Cell Epitope Mapping, Reverse Vaccinology, and Immunoinformatics. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2020, 24, 195–204.

- Counoupas, C.; Ferrell, K.C.; Ashhurst, A.; Bhattacharyya, N.D.; Nagalingam, G.; Stewart, E.L.; Feng, C.G.; Petrovsky, N.; Britton, W.J.; Triccas, J.A. Mucosal Delivery of a Multistage Subunit Vaccine Promotes Development of Lung-Resident Memory T Cells and Affords Interleukin-17-Dependent Protection against Pulmonary Tuberculosis. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 1–12.

- Woodworth, J.S.; Clemmensen, H.S.; Battey, H.; Dijkman, K.; Lindenstrøm, T.; Laureano, R.S.; Taplitz, R.; Morgan, J.; Aagaard, C.; Rosenkrands, I.; et al. A Mycobacterium Tuberculosis-Specific Subunit Vaccine That Provides Synergistic Immunity upon Co-Administration with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6658.

- Moreira, M.; Ruggiero, A.; Esposito, L.; Choi, H.-G.; Kim, H.-J.; Berisio, R. Structural Features of HtpGMtb and HtpG-ESAT6Mtb Vaccine Antigens against Tuberculosis: Molecular Determinants of Antigenic Synergy and Cytotoxicity Modulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 158, 305–317.

- Choi, H.-G.; Choi, S.; Back, Y.W.; Paik, S.; Park, H.-S.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, H.; Cha, S.B.; Choi, C.H.; Shin, S.J.; et al. Rv2299c, a Novel Dendritic Cell-Activating Antigen of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, Fused-ESAT-6 Subunit Vaccine Confers Improved and Durable Protection against the Hypervirulent Strain HN878 in Mice. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 19947–19967.

- Ruggiero, A.; Choi, H.-G.; Barra, G.; Squeglia, F.; Back, Y.W.; Kim, H.-J.; Berisio, R. Structure Based Design of Effective HtpG-Derived Vaccine Antigens against M. Tuberculosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 964645.

- Mader, S.L.; Lopez, A.; Lawatscheck, J.; Luo, Q.; Rutz, D.A.; Gamiz-Hernandez, A.P.; Sattler, M.; Buchner, J.; Kaila, V.R.I. Conformational Dynamics Modulate the Catalytic Activity of the Molecular Chaperone Hsp90. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1410.

More

Information

Subjects:

Immunology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

697

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

07 Feb 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No