| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | El Hadji M Dioum | -- | 2521 | 2023-02-02 02:43:03 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 2521 | 2023-02-02 10:15:52 | | |

Video Upload Options

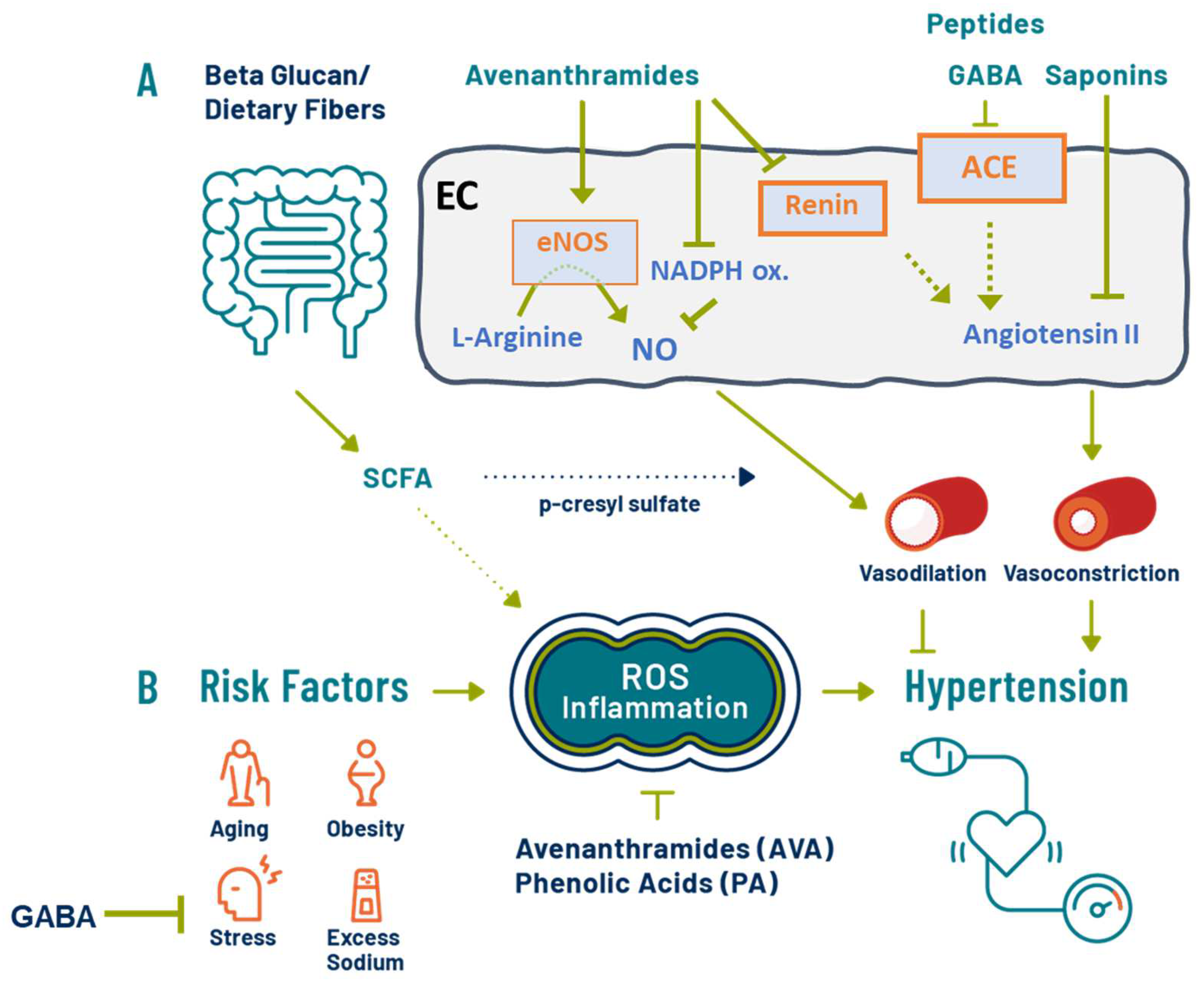

Hypertension (HTN) is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cognitive decline. Elevations in blood pressure (BP) leading to HTN can be found in young adults with increased prevalence as people age. Oats can decrease CVD risk via an established effect of β-glucan on the attenuation of blood cholesterol. Oats deliver several beneficial dietary components with putative beneficial effects on BP or endothelial function, such as β-glucan, γ-amino butyric acid (GABA), and phytochemicals such as avenanthramides.

1. Introduction

2. Effects of Oat on Blood Pressure

2.1. Oats and Blood Pressure

Subgroup analysis for β-glucan sources showed reductions in SBP and DBP [8][24]. In a meta-analysis of normotensive adults, sensitivity analysis suggested that neither age nor body mass index (BMI) had a marked impact on the effect of fiber interventions and BP [8]. A separate meta-analysis including adults with HTN found no effects from fiber amounts, study design, and type of administration; although higher reductions were seen in interventions lasting more than 7 weeks, the reductions in BP were also influenced by the HTN status in subjects [24]. Taken together, these data support that responses are more robust in HTN than in normotensive subjects and that the amount of fiber/intervention product is essential. However, although the oat findings were attributed to β-glucan, the interventions utilized in the meta-analyses included studies primarily using oatmeal/porridge, oat cereal, and foods made with oat bran, not isolated β-glucan fiber. Therefore, although some conclusions were attributed to β-glucan effects, the other components in oats may also be contributing to the effect of lowering BP.

2.2. Oat Composition and Bioactives

Oat is unlike many other cereal grains based on its composition; it is primarily consumed as a whole grain, although oat bran is often used in many food applications [7]. Several oat varieties are grown across the globe and include husked oats (Avena sativa L.), large naked oats (Avena nuda I.), small naked oats (Avena nudibrevis), wild red oats (Avena steriles), and wild oats (Avena fatua) among others [7][21].

Oat Sprouts as a Source of Bioactives

Antihypertensive Effects of Oats

Dietary Fiber and SCFA

Diets high in fiber, particularly soluble fibers (e.g., β-glucan), are recommended to decrease elevated BP [8][11][24][39][40][41][42], and some evidence suggests they function by decreasing glucose uptake and therefore decreasing insulin release [43]. Emerging evidence suggests a healthy microbiome is also important in BP management [7][15][44][45]. For example, SCFAs produced by the microbiota have been shown to have vasodilating effects and anti-inflammatory properties, which can attenuate hypertensive tissue damage [7]. In a clinical pilot study, increases in fecal SCFA decreases serum p-cresyl sulfate, and improvements in endothelial function via flow-mediated dilation (FMD) have been observed after consumption of a pasta enriched with barley β-glucans [46][47]. However, in another study with 210 mildly hypercholesterolemic Chinese adults, 80 g oats delivering 3 g β-glucans and 56.8 g polyphenols did not significantly change plasma SCFA but did result in putative beneficial changes in gut microbiota after 45 days [48].

Oat Phenolics and Avenanthramides

Avenanthramides have established physiological properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-thrombotic benefits, with reportedly higher antioxidant activity compared to that of other phenolic compounds in vitro [22][23]. Cell culture studies have found that avenanthramides can increase NO levels and endothelial NO synthase expression in vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells, thus potentially affecting NO-dependent vasodilation [17][36]. In vitro data suggest the effect on NO may occur via reducing cellular superoxide levels, or acting as NADPH oxidase inhibitors, thereby reducing NO degradation [49]. Avenanthramides have also been shown to inhibit the adhesion of monocytes to vascular endothelial cells and release inflammatory activators from macrophages, and exert anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic activities in transformed cells [26][50]. Increasingly, inflammation is being linked to HTN and, particularly hypertensive tissue damage [51]. Further, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells of the immune system can promote elevations in BP [51]. Therefore, the potential beneficial impact of oat polyphenols on inflammation and immune function could also contribute to the attenuation of elevated BP.

Oat Bioactive Peptides and γ-Aminobutyric Acids (GABA)

References

- Centers for Disease Control. High Blood Pressure Symptoms and Causes. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/about.htm (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive Summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2018, 138, e426–e483.

- Ferrario, C.M.; Groban, L.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; VonCannon, J.L.; Wright, K.N.; Ahmad, S. The renin–angiotensin system biomolecular cascade: A 2022 update of newer insights and concepts. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 36–47.

- Neter, J.E.; Stam, B.E.; Kok, F.J.; Grobbee, D.E.; Geleijnse, J.M. Influence of Weight Reduction on Blood Pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension 2003, 42, 878–884.

- Mahinrad, S.; Sorond, F.A.; Gorelick, P.B. Hypertension and cognitive dysfunction: A review of mechanisms, life-course observational studies and clinical trial results. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 22, 1429–1449.

- Verdecchia, P.; Cavallini, C.; Angeli, F. Advances in the Treatment Strategies in Hypertension: Present and Future. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 72.

- Bouchard, J.; Valookaran, A.F.; Aloud, B.M.; Raj, P.; Malunga, L.N.; Thandapilly, S.J.; Netticadan, T. Impact of oats in the prevention/management of hypertension. Food Chem. 2022, 381, 132198.

- Evans, C.E.L.; Greenwood, D.C.; Threapleton, D.E.; Cleghorn, C.L.; Nykjaer, C.; Woodhead, C.E.; Gale, C.P.; Burley, V.J. Effects of dietary fibre type on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of healthy individuals. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 897–911.

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Veronesi, M.; Fogacci, F. Dietary Intervention to Improve Blood Pressure Control: Beyond Salt Restriction. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2021, 28, 547–553.

- Borghi, C.; Cicero, A.F.G. Nutraceuticals with a clinically detectable blood pressure-lowering effect: A review of available randomized clinical trials and their meta-analyses. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 163–171.

- Aleixandre, A.; Miguel, M. Dietary fiber and blood pressure control. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 1864–1871.

- Chang, H.-C.; Huang, C.-N.; Yeh, D.-M.; Wang, S.-J.; Peng, C.-H.; Wang, C.-J. Oat Prevents Obesity and Abdominal Fat Distribution, and Improves Liver Function in Humans. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2013, 68, 18–23.

- Rebello, C.J.; Johnson, W.D.; Martin, C.K.; Han, H.; Chu, Y.-F.; Bordenave, N.; Van Klinken, B.J.W.; O’Shea, M.; Greenway, F.L. Instant Oatmeal Increases Satiety and Reduces Energy Intake Compared to a Ready-to-Eat Oat-Based Breakfast Cereal: A Randomized Crossover Trial. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016, 35, 41–49.

- Saltzman, E.; Das, S.K.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Dallal, G.E.; Corrales, A.; Schaefer, E.J.; Greenberg, A.S.; Roberts, S.B. An Oat-Containing Hypocaloric Diet Reduces Systolic Blood Pressure and Improves Lipid Profile beyond Effects of Weight Loss in Men and Women. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1465–1470.

- Wouk, J.; Dekker, R.F.; Queiroz, E.A.; Barbosa-Dekker, A.M. β-Glucans as a panacea for a healthy heart? Their roles in preventing and treating cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 177, 176–203.

- El Khoury, D.; Cuda, C.; Luhovyy, B.L.; Anderson, G.H. Beta glucan: Health benefits in obesity and metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 851362.

- Meydani, M. Potential health benefits of avenanthramides of oats. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 731–735.

- Mathews, R.; Kamil, A.; Chu, Y. Global review of heart health claims for oat beta-glucan products. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 78–97.

- Dioum, E.H.M.; Schneider, K.L.; Vigerust, D.J.; Cox, B.D.; Chu, Y.; Zachwieja, J.J.; Furman, D. Oats Lower Age-Related Systemic Chronic Inflammation (iAge) in Adults at Risk for Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4471.

- Wolever, T.M.S.; Rahn, M.; Dioum, E.; Spruill, S.E.; Ezatagha, A.; Campbell, J.E.; Jenkins, A.L.; Chu, Y. An Oat β-Glucan Beverage Reduces LDL Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Men and Women with Borderline High Cholesterol: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2655–2666.

- Singh, R.; De, S.; Belkheir, A. Avena sativa (Oat), A Potential Neutraceutical and Therapeutic Agent: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 126–144.

- Perrelli, A.; Goitre, L.; Salzano, A.M.; Moglia, A.; Scaloni, A.; Retta, S.F. Biological Activities, Health Benefits, and Therapeutic Properties of Avenanthramides: From Skin Protection to Prevention and Treatment of Cerebrovascular Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 6015351.

- Kim, I.-S.; Hwang, C.-W.; Yang, W.-S.; Kim, C.-H. Multiple Antioxidative and Bioactive Molecules of Oats (Avena sativa L.) in Human Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1454.

- Khan, K.; Jovanovski, E.; Ho, H.V.T.; Marques, A.C.R.; Zurbau, A.; Mejia, S.B.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Vuksan, V. The effect of viscous soluble fiber on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 3–13.

- Raguindin, P.F.; Itodo, O.A.; Stoyanov, J.; Dejanovic, G.M.; Gamba, M.; Asllanaj, E.; Minder, B.; Bussler, W.; Metzger, B.; Muka, T.; et al. A systematic review of phytochemicals in oat and buckwheat. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 127982.

- Chen, O.; Mah, E.; Dioum, E.; Marwaha, A.; Shanmugam, S.; Malleshi, N.; Sudha, V.; Gayathri, R.; Unnikrishnan, R.; Anjana, R.M.; et al. The Role of Oat Nutrients in the Immune System: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1048.

- Soycan, G.; Schär, M.Y.; Kristek, A.; Boberska, J.; Alsharif, S.N.; Corona, G.; Shewry, P.R.; Spencer, J.P. Composition and content of phenolic acids and avenanthramides in commercial oat products: Are oats an important polyphenol source for consumers? Food Chem. X 2019, 3, 100047.

- Aparicio-García, N.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Crespo Perez, L.; Fernández, C.F.; Alba, C.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Peñas, E. A Novel Sprouted Oat Fermented Beverage: Evaluation of Safety and Health Benefits for Celiac Individuals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2522.

- Tang, S.; Mao, G.; Yuan, Y.; Weng, Y.; Zhu, R.; Cai, C.; Mao, J. Optimization of oat seed steeping and germination temperatures to maximize nutrient content and antioxidant activity. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14683.

- Aparicio-García, N.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Peñas, E. Changes in protein profile, bioactive potential and enzymatic activities of gluten-free flours obtained from hulled and dehulled oat varieties as affected by germination conditions. LWT 2020, 134, 109955.

- Samia El-Safy, F.; Rabab, H.A.S.; Ensaf Mukhtar, Y.Y. The Impact of Soaking and Germination on Chemical Composition, Carbohydrate Fractions, Digestibility, Antinutritional Factors and Minerals Content of Some Legumes and Cereals Grain Seeds. Alex. Sci. Exch. J. 2013, 34, 499–513.

- Herreman, L.; Nommensen, P.; Pennings, B.; Laus, M.C. Comprehensive overview of the quality of plant- And animal-sourced proteins based on the digestible indispensable amino acid score. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 5379–5391.

- Xu, J.G.; Hu, Q.P.; Duan, J.L.; Tian, C.R. Dynamic Changes in γ-Aminobutyric Acid and Glutamate Decarboxylase Activity in Oats (Avena nuda L.) during Steeping and Germination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 9759–9763.

- Ding, J.; Johnson, J.; Chu, Y.F.; Feng, H. Enhancement of γ-aminobutyric acid, avenanthramides, and other health-promoting metabolites in germinating oats (Avena sativa L.) treated with and without power ultrasound. Food Chem. 2019, 283, 239–247.

- Damazo-Lima, M.; Rosas-Pérez, G.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Pérez-Ramírez, I.F.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E.; de Los Ríos, E.A.; Ramos-Gomez, M. Chemopreventive Effect of the Germinated Oat and Its Phenolic-AVA Extract in Azoxymethane/Dextran Sulfate Sodium (AOM/DSS) Model of Colon Carcinogenesis in Mice. Foods 2020, 9, 169.

- Hu, C.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sang, S. Quantitative Analysis and Anti-inflammatory Activity Evaluation of the A-Type Avenanthramides in Commercial Sprouted Oat Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13068–13075.

- Tain, Y.-L.; Hsu, C.-N. Oxidative Stress-Induced Hypertension of Developmental Origins: Preventive Aspects of Antioxidant Therapy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 511.

- Alexander, S.; Ostfeld, R.J.; Allen, K.; Williams, K.A. A plant-based diet and hypertension. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 327–330.

- Hartley, L.; May, M.D.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Rees, K. Dietary fibre for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 1, CD011472.

- Reynolds, A.N.; Akerman, A.; Kumar, S.; Pham, H.T.D.; Coffey, S.; Mann, J. Dietary fibre in hypertension and cardiovascular disease management: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 139.

- Whelton, S.P.; Hyre, A.D.; Pedersen, B.; Yi, Y.; Whelton, P.K.; He, J. Effect of dietary fiber intake on blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials. J. Hypertens. 2005, 23, 475–481.

- Streppel, M.T.; Arends, L.R.; Veer, P.V.; Grobbee, D.E.; Geleijnse, J.M. Dietary Fiber and Blood Pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 150–156.

- Paudel, D.; Dhungana, B.; Caffe, M.; Krishnan, P. A Review of Health-Beneficial Properties of Oats. Foods 2021, 10, 2591.

- Poll, B.G.; Cheema, M.U.; Pluznick, J.L. Gut Microbial Metabolites and Blood Pressure Regulation: Focus on SCFAs and TMAO. Physiology 2020, 35, 275–284.

- Al Khodor, S.; Reichert, B.; Shatat, I.F. The Microbiome and Blood Pressure: Can Microbes Regulate Our Blood Pressure? Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 138.

- Cosola, C.; De Angelis, M.; Rocchetti, M.T.; Montemurno, E.; Maranzano, V.; Dalfino, G.; Manno, C.; Zito, A.; Gesualdo, M.; Ciccone, M.M.; et al. Beta-Glucans Supplementation Associates with Reduction in P-Cresyl Sulfate Levels and Improved Endothelial Vascular Reactivity in Healthy Individuals. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169635.

- De Angelis, M.; Montemurno, E.; Vannini, L.; Cosola, C.; Cavallo, N.; Gozzi, G.; Maranzano, V.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Gesualdo, L. Effect of Whole-Grain Barley on the Human Fecal Microbiota and Metabolome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 7945–7956.

- Xu, D.; Feng, M.; Chu, Y.; Wang, S.; Shete, V.; Tuohy, K.M.; Liu, F.; Zhou, X.; Kamil, A.; Pan, D.; et al. The Prebiotic Effects of Oats on Blood Lipids, Gut Microbiota, and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Mildly Hypercholesterolemic Subjects Compared with Rice: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 787797.

- Serreli, G.; Le Sayec, M.; Thou, E.; Lacour, C.; Diotallevi, C.; Dhunna, M.A.; Deiana, M.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Corona, G. Ferulic Acid Derivatives and Avenanthramides Modulate Endothelial Function through Maintenance of Nitric Oxide Balance in HUVEC Cells. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2026.

- Kim, S.J.; Jung, C.W.; Anh, N.H.; Kim, S.W.; Park, S.; Kwon, S.W.; Lee, S.J. Effects of Oats (Avena sativa L.) on Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 722866.

- Wenzel, U.O.; Ehmke, H.; Bode, M. Immune mechanisms in arterial hypertension. Recent advances. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 385, 393–404.

- Yu, G.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Fan, J. In vitro inhibition of platelet aggregation by peptides derived from oat (Avena sativa L.), highland barley (Hordeum vulgare Linn. var. nudum Hook. f.), and buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) proteins. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 577–586.

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; You, H.; Yu, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Ding, L. Identification and Characterization of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-IV Inhibitory Peptides from Oat Proteins. Foods 2022, 11, 1406.

- Esfandi, R.; Willmore, W.G.; Tsopmo, A. Peptidomic analysis of hydrolyzed oat bran proteins, and their in vitro antioxidant and metal chelating properties. Food Chem. 2019, 279, 49–57.

- Esfandi, R.; Seidu, I.; Willmore, W.; Tsopmo, A. Antioxidant, pancreatic lipase, and α-amylase inhibitory properties of oat bran hydrolyzed proteins and peptides. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e13762.

- Sánchez-Velázquez, O.A.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Mondor, M.; Ribéreau, S.; Arcand, Y.; Mackie, A.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J. Impact of in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on peptide profile and bioactivity of cooked and non-cooked oat protein concentrates. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 93–104.

- Bleakley, S.; Hayes, M.; Shea, N.O.; Gallagher, E.; Lafarga, T. Predicted Release and Analysis of Novel ACE-I, Renin, and DPP-IV Inhibitory Peptides from Common Oat (Avena sativa) Protein Hydrolysates Using in Silico Analysis. Foods 2017, 6, 108.

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, P.; Tian, H.; Li, X.; Chen, X. Isolation of novel ACE-inhibitory peptide from naked oat globulin hydrolysates in silico approach: Molecular docking, in vivo antihypertension and effects on renin and intracellular endothelin-1. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 1328–1337.

- Cheung, I.W.Y.; Nakayama, S.; Hsu, M.N.K.; Samaranayaka, A.G.P.; Li-Chan, E.C.Y. Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Hydrolysates from Oat (Avena sativa) Proteins by In Silico and In Vitro Analyses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 9234–9242.

- Oketch-Rabah, H.A.; Madden, E.F.; Roe, A.L.; Betz, J.M. United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Safety Review of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA). Nutrients 2021, 13, 2742.

- Ngo, D.-H.; Vo, T.S. An Updated Review on Pharmaceutical Properties of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid. Molecules 2019, 24, 2678.

- Cai, S.; Gao, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, O.; Wu, W.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, F.; Ji, B. Evaluation of γ- aminobutyric acid, phytate and antioxidant activity of tempeh-like fermented oats (Avena sativa L.) prepared with different filamentous fungi. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 2544–2551.

- Xu, J.G.; Tian, C.R.; Hu, Q.P.; Luo, J.Y.; Wang, X.D.; Tian, X.D. Dynamic Changes in Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Oats (Avena nuda L.) during Steeping and Germination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10392–10398.

- Xie, W.; Ashraf, U.; Zhong, D.; Lin, R.; Xian, P.; Zhao, T.; Feng, H.; Wang, S.; Duan, M.; Tang, X.; et al. Application of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and nitrogen regulates aroma biochemistry in fragrant rice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 3784–3796.