Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ilker Uçkay | -- | 1129 | 2023-02-02 01:52:06 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -6 word(s) | 1123 | 2023-02-02 03:00:42 | | | | |

| 3 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 1123 | 2023-02-06 02:00:15 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Soldevila-Boixader, L.; Fernández, A.P.; Laguna, J.M.; Uçkay, I. Local Antibiotics in Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40747 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Soldevila-Boixader L, Fernández AP, Laguna JM, Uçkay I. Local Antibiotics in Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40747. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Soldevila-Boixader, Laura, Alberto Pérez Fernández, Javier Muñoz Laguna, Ilker Uçkay. "Local Antibiotics in Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40747 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Soldevila-Boixader, L., Fernández, A.P., Laguna, J.M., & Uçkay, I. (2023, February 02). Local Antibiotics in Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40747

Soldevila-Boixader, Laura, et al. "Local Antibiotics in Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections." Encyclopedia. Web. 02 February, 2023.

Copy Citation

Along with the increasing global burden of diabetes, diabetic foot infections (DFI) and diabetic foot osteomyelitis (DFO) remain major challenges for patients and society. Despite progress in the development of prominent international guidelines, the optimal medical treatment for DFI and DFO remains unclear as to whether local antibiotics, that is, topical agents and local delivery systems, should be used alone or concomitant to conventional systemic antibiotics.

diabetic foot infection

osteomyelitis

local antibiotics

1. Introduction

Diabetic foot infections (DFI), including diabetic foot osteomyelitis (DFO), represent a societal challenge associated with substantial morbidity, prolonged hospitalizations, prospective amputations, and higher overall healthcare costs [1]. Diabetes prevalence varies between countries of different economic levels, being generally higher in low-income countries (12.3%) than in high-income countries (6.6%), although these differences are not easily explained by the distribution of conventional risk factors [2]. In general, systemic antibiotics are recommended as a reference treatment for infected diabetic feet [3][4], while local antimicrobial agents and surgically implanted delivery systems have been overlooked. Thus far, local antibiotic therapies have been studied within the context of non-diabetic orthopedic infections and orthopedic trauma, mainly as antibiotic-containing beads and antibiotic-containing cement. These interventions have targeted the treatment of osteomyelitis, and the prevention and therapy of implant infections [5][6]. In the management of an infected diabetic foot, clinicians often encounter three scenarios in which local antibiotic use could be advantageous: (1) infected diabetic foot ulcers (DFU), (2) soft tissue infections without DFO, and (3) DFO. The emergence and attractiveness of local antibiotics for DFI and DFO rely on the opportunity they offer to reduce the extent of antimicrobials needed, their ability to achieve high antibiotic concentrations in the localized infected area, their limited systemic absorption and reduced adverse events, and their evident safety in relation to multidrug resistance [7][8]. The disadvantages are few and may include local skin hypersensitivity or contact dermatitis, prolonged wound discharge, the relative burden associated with frequent reapplications over time, and the possible unintended contamination of opened multidose containers [8].

It is worth mentioning that in the local treatment of DFI and DFO, aminoglycosides and vancomycin are the most studied antibiotics, having both broad-spectrum activity and being able to be incorporated into any delivery vehicle. The biological properties of these two antibiotics also allow them to remain thermostable during the exothermic reaction that occurs during the polymerization of the cement in local applications, ultimately delivering a significantly higher concentration locally than via the blood system [9].

2. Topical Antibiotics in Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Postoperative Wounds in a Diabetic Foot

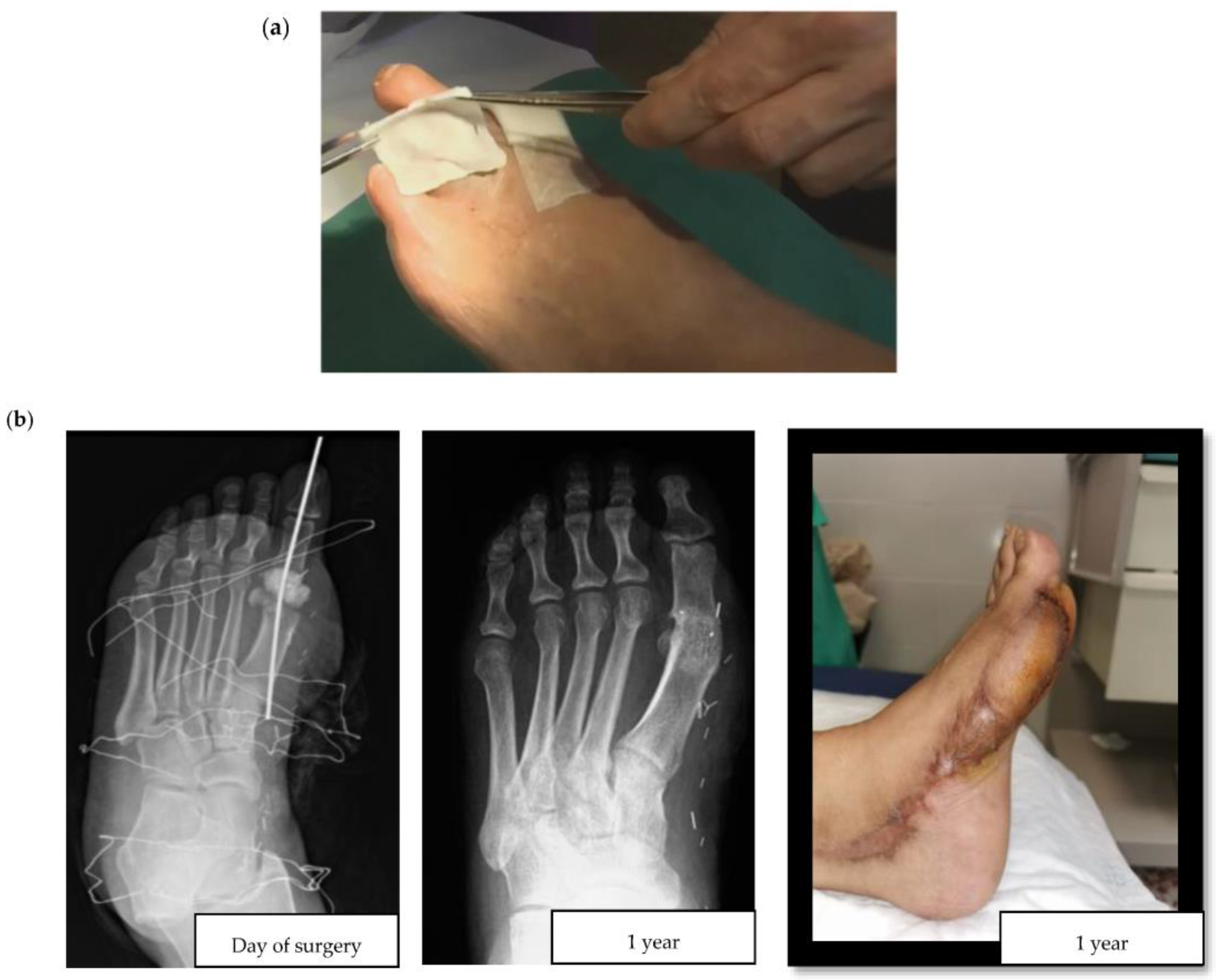

Researchers consistently apply the term topical to refer to the local administration of antibiotics through an infected diabetic foot ulcer (DFU). Topical antibiotic interventions have previously been studied in the assessment of the bioburden and biofilm of diabetic foot wounds [10]. For example, an in vitro experiment compared the efficacy of topical vancomycin and gentamicin to systemic antibiotics for the eradication of polymicrobial biofilms. The authors observed a bioburden reduction of 5 and 8 logarithms (colony forming units per milliliter), a finding with uncertain yet promising clinical relevance, and supportive of further studies to reveal the usefulness of topical antibiotic strategies in the surgical treatment of DFIs [11]. When considering the multiple topical antimicrobials available, it is also worth highlighting that a recent high-quality systematic review failed to show the superiority of any particular topical antimicrobial [12]. This lack of superiority could be partially explained by the local agent choices, encompassing a wide range of antiseptics, antibiotics, and antimicrobial dressings. More consistency in design is seen in clinical studies of local agents in DFIs since the gentamicin collagen sponge and the superficial pexiganan peptide (Figure 1a) tend to be incorporated.

Figure 1. (a) Application of a collagen sponge on a diabetic foot wound (courtesy of Dr. Ilker Uçkay); (b) Clinical case of a hallux valgus osteomyelitis with bone resection, filling with Cerament G® and a flap.

Interestingly, in vitro studies have shown that the kinetics of antibiotic release from gentamicin collagen sponge matrices can reach 95% in as little as 1.5 h [13][14]. A plausible explanation is that collagen may produce scaffolds for fibrin deposition, resulting in the healing of tissue defects and the acceleration of wound healing. It is noteworthy that the success of gentamicin collagen sponges has been documented since 1997 [15]. For its part, pexiganan, an antimicrobial synthetic peptide and analogue of the magainin peptide, has shown similarly promising in vitro results, as judged by the susceptibility of bacteria isolated from the infected diabetic foot to pexiganan in 1999. However, the first therapeutic experience with gentamicin in an infected diabetic foot did not occur until 2008 [16][17].

3. Local Delivery Antibiotic Systems in Operated Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis

There are two major challenges associated with DFO surgeries: postoperative wound healing in the operated, and ischemia triggered by the residual death space of the former bone. In DFO treatment, two main types of antibiotic delivery system materials are currently available: non-absorbable and absorbable. According to the explored literature, the most frequently used non-absorbable material in DFO is polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)—an acrylic used extensively in orthopedic surgery for chronic osteomyelitis and implant-related infections [18][19]. Some of the most common antibiotic-loaded commercial PMMA cements include Cemex®, Simplex®, Eurofix®, Palacos®, Copal®, and Refobacin®. As with all non-absorbable materials, the main disadvantage of PMMA is its surgical removal, resulting in additional intervention following the release of all drugs. Alternatively, there are hybrids of biodegradable carrier systems that take advantage of different properties to improve local antibiotic release. They have different presentations, such as Cerament G/V® (see Figure 1b for a clinical case example) or Stimulan® [20]. The development and use of contemporary absorbable biomaterials is an area of ongoing advancement. These materials have some advantages compared to PMMA, including better osteointegration and the lack of need for surgical removal. In this respect, the importance of considering the composition of these materials should also be highlighted, especially as to whether or not they contain hydroxyapatite, which is highly osteoconductive and promotes bone ingrowth. For example, the unique ratio of hydroxyapatite and calcium sulphate in Cerament® makes it particularly suitable for absorption and stimulation of new bone formation at the same rate. In contrast, Stimulan® only contains hemihydrate calcium sulfate, which retains its absorbable properties, but sacrifices osteoconductivity and bone growth.

Table 1 summarizes the key properties of the three classes of commercial antibiotics, based on their local delivery systems. Other delivery systems are mainly used for long bones, and only exceptionally in the infected diabetic foot.

Table 1. Local delivery antibiotics in diabetic foot osteomyelitis.

| Commercial Antibiotic Mode of Administration |

Composition (%) | Absorbable | Generic Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cemex®, Simplex®, Eurofix®, Palacos®, Copal®, Refobacin® Antibiotic-loaded PMMA cement |

Polymethylmethacrylate (100%) | No | GEN/VAN/TOB or CLIN |

| Cerament® Injectable synthetic bone void filler |

Calcium sulphate (60%) Hydroxyapatite (40%) |

Yes | GEN/VAN |

| Stimulan® Injectable synthetic bone void filler or beads |

Calcium sulphate (100%) | Yes | GEN/VAN/TOB |

Abbreviations: CLIN, clindamycin; GEN, gentamicin; PMMA, polymethylmethacrylate; TOB, tobramycin; VAN, vancomycin.

References

- Lavery, L.A.; Armstrong, D.G.; Wunderlich, R.P.; Mohler, M.J.; Wendel, C.S.; Lipsky, B.A. Risk Factors for Foot Infections in Individuals With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1288–1293.

- Dagenais, G.R.; Gerstein, H.C.; Zhang, X.; McQueen, M.; Lear, S.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Mohan, V.; Mony, P.; Gupta, R.; Kutty, V.R.; et al. Variations in Diabetes Prevalence in Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries: Results From the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 780–787.

- Lipsky, B.A.; Berendt, A.R.; Cornia, P.B.; Pile, J.C.; Peters, E.J.G.; Armstrong, D.G.; Deery, H.G.; Embil, J.M.; Joseph, W.S.; Karchmer, A.W.; et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, e132–e173.

- Lipsky, B.A.; Senneville, É.; Abbas, Z.G.; Aragón-Sánchez, J.; Diggle, M.; Embil, J.M.; Kono, S.; Lavery, L.A.; Malone, M.; Asten, S.A.; et al. Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Foot Infection in Persons with Diabetes (IWGDF 2019 Update). Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3280.

- Haddad, F.S.; Masri, B.A.; Campbell, D.; McGraw, R.W.; Beauchamp, C.P.; Duncan, C.P. The PROSTALAC Functional Spacer in Two-Stage Revision for Infected Knee Replacements. J. Bone. Jt. Surg. 2000, 82, 807–812.

- Hofmann, A.A.; Goldberg, T.D.; Tanner, A.M.; Cook, T.M. Ten-Year Experience Using an Articulating Antibiotic Cement Hip Spacer for the Treatment of Chronically Infected Total Hip. J. Arthroplast. 2005, 20, 874–879.

- Markakis, K.; Faris, A.R.; Sharaf, H.; Faris, B.; Rees, S.; Bowling, F.L. Local Antibiotic Delivery Systems: Current and Future Applications for Diabetic Foot Infections. Int. J. Low Extrem Wounds 2018, 17, 14–21.

- Lipsky, B.A.; Hoey, C. Topical Antimicrobial Therapy for Treating Chronic Wounds. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 1541–1549.

- Wininger, D.A.; Fass, R.J. Antibiotic-Impregnated Cement and Beads for Orthopedic Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 2675–2679.

- Lavigne, J.-P.; Sotto, A.; Dunyach-Remy, C.; Lipsky, B.A. New Molecular Techniques to Study the Skin Microbiota of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2015, 4, 38–49.

- Crowther, G.S.; Callaghan, N.; Bayliss, M.; Noel, A.; Morley, R.; Price, B. Efficacy of Topical Vancomycin- and Gentamicin-Loaded Calcium Sulfate Beads or Systemic Antibiotics in Eradicating Polymicrobial Biofilms Isolated from Diabetic Foot Infections within an In Vitro Wound Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e02012-20.

- Dumville, J.C.; Lipsky, B.A.; Hoey, C.; Cruciani, M.; Fiscon, M.; Xia, J. Topical Antimicrobial Agents for Treating Foot Ulcers in People with Diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 70–76.

- Swieringa, A.J.; Goosen, J.H.M.; Jansman, F.G.A.; Tulp, N.J.A. In Vivo Pharmacokinetics of a Gentamicin-Loaded Collagen Sponge in Acute Periprosthetic Infection: Serum Values in 19 Patients. Acta Orthop. 2008, 79, 637–642.

- Kilian, O.; Hossain, H.; Flesch, I.; Sommer, U.; Nolting, H.; Chakraborty, T.; Schnettler, R. Elution Kinetics, Antimicrobial Efficacy, and Degradation and Microvasculature of a New Gentamicin-Loaded Collagen Fleece. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2008, 90B, 210–222.

- Faludi, S.; Kádár, E.; Kószegi, G.; Jakab, F. Experience Acquired by Applying Gentamicin-Sponge. Acta. Chir. Hung. 1997, 36, 81–82.

- Ge, Y.; MacDonald, D.; Henry, M.M.; Hait, H.I.; Nelson, K.A.; Lipsky, B.A.; Zasloff, M.A.; Holroyd, K.J. In Vitro Susceptibility to Pexiganan of Bacteria Isolated from Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1999, 35, 45–53.

- Lipsky, B.A.; Holroyd, K.J.; Zasloff, M. Topical versus Systemic Antimicrobial Therapy for Treating Mildly Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blinded, Multicenter Trial of Pexiganan Cream. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 1537–1545.

- Roeder, B.; van Gils, C.C.; Maling, S. Antibiotic Beads in the Treatment of Diabetic Pedal Osteomyelitis. J. Foot. Ankle. Surg. 2000, 39, 124–130.

- Schade, V.L.; Roukis, T.S. The Role of Polymethylmethacrylate Antibiotic-Loaded Cement in Addition to Debridement for the Treatment of Soft Tissue and Osseous Infections of the Foot and Ankle. J. Foot. Ankle. Surg. 2010, 49, 55–62.

- En, A.; Sanitarios, P. Cementos Óseos Con Antibiótico. Panor. Actual del Medicam. 2016, 40, 634–638.

More

Information

Subjects:

Others

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

716

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 Feb 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No