Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shahid Ahmed | -- | 1272 | 2023-02-02 01:51:05 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 1272 | 2023-02-02 02:57:27 | | | | |

| 3 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 1272 | 2023-02-07 01:37:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Pati, S.; Irfan, W.; Jameel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K. Management of Obesity in Cancer Survivors. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40746 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Pati S, Irfan W, Jameel A, Ahmed S, Shahid RK. Management of Obesity in Cancer Survivors. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40746. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Pati, Sukanya, Wadeed Irfan, Ahmad Jameel, Shahid Ahmed, Rabia K. Shahid. "Management of Obesity in Cancer Survivors" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40746 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Pati, S., Irfan, W., Jameel, A., Ahmed, S., & Shahid, R.K. (2023, February 02). Management of Obesity in Cancer Survivors. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40746

Pati, Sukanya, et al. "Management of Obesity in Cancer Survivors." Encyclopedia. Web. 02 February, 2023.

Copy Citation

Many cancer survivors experience weight gain following the diagnosis of cancer and its treatment. As described above, obesity not only increases the risk of recurrence in some cancers but also increases the risk of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and poor quality of life.

obesity

cancer

malignancy

overweight

1. Introduction

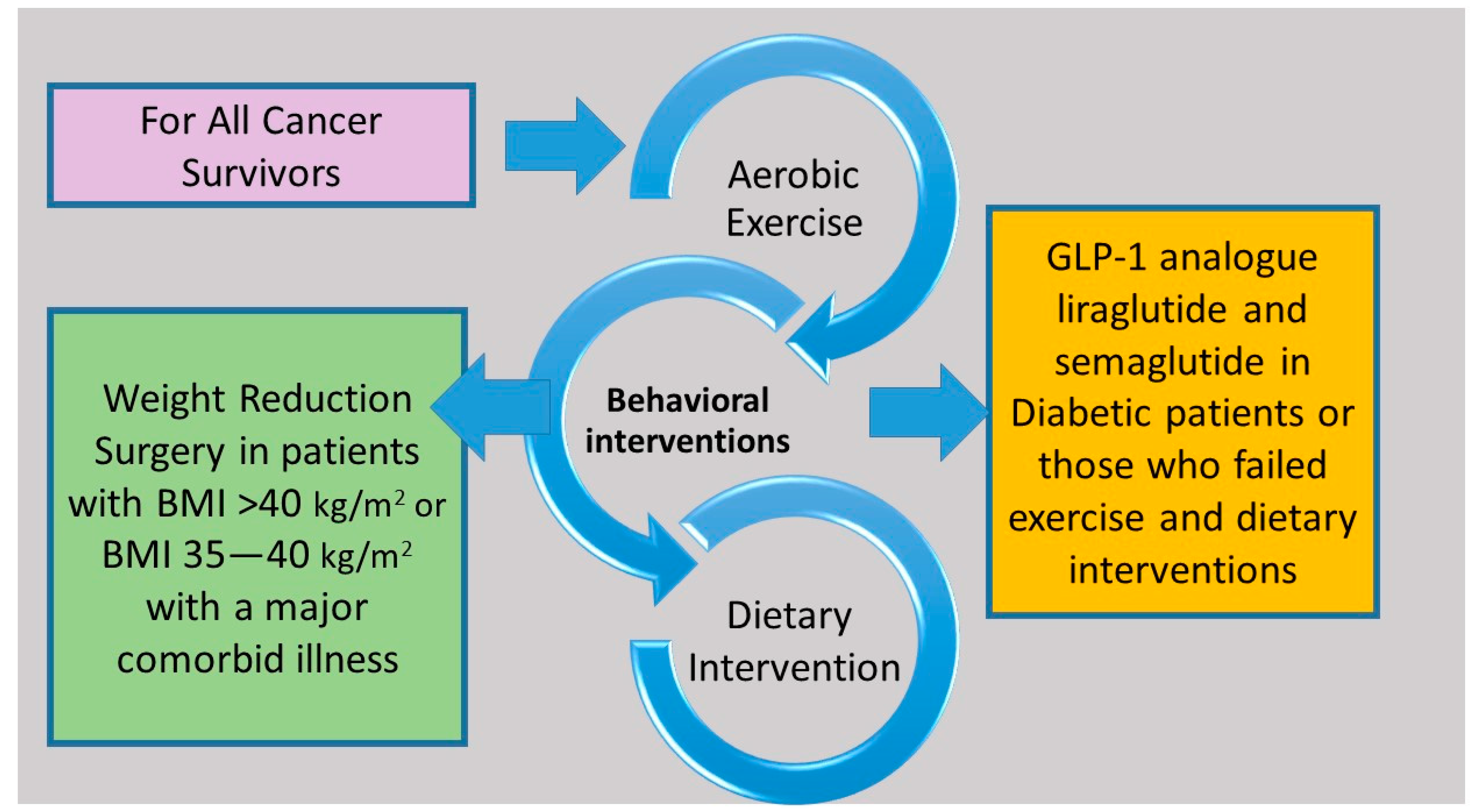

Evidence demonstrates that structured exercise combined with dietary support for weight loss results in greater weight loss than exercise or diet alone and has the greatest impact on blood-borne biomarkers linked to common cancers, such as insulin resistance and circulating levels of sex hormones, leptin, and inflammatory markers [1][2][3][4][5]. Many cancer guidelines recommend that survivors maintain a healthy weight, but there is a lack of evidence regarding which weight loss method to recommend [6][7][8]. Lifestyle interventions that include diet, exercise, and behavior therapy are the mainstay of interventions related to lifestyle modification (Figure 1). Pharmacological and surgical interventions are not well studied in cancer survivors. A Cochrane meta-analysis of 20 studies involving 2028 breast cancer survivors evaluated the effect of different body weight loss approaches in overweight or obese breast cancer survivors and found that weight loss interventions, especially multimodal interventions that include diet, exercise, and psychosocial interventions resulted in a reduction in body weight, body mass index, waist circumference, and better overall quality of life [9].

Figure 1. Structured exercise in combination with dietary support and behavior therapy are effective interventions for all cancer survivors. Treatment with glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues and bariatric surgery can be considered in selected cancer survivors.

2. Diet

A consistent caloric deficit regardless of the type of diet results in weight loss [10][11]. The 2-year POUNDS LOST (Preventing Overweight Using Novel Dietary Strategies) trial randomized study participants into four diets groups with a deficit of 750 kcal per day and showed that there was no difference in the short- and long-term weight loss among the four groups [10]. However, macronutrient components of a low caloric diet can contribute to cardiometabolic outcomes [12]. The Diet and Androgen-5 (DIANA-5) trial examined whether a dietary adjustment based on macrobiotic and Mediterranean diet principles can lower the incidence of events associated with breast cancer. The early results showed that the DIANA-5 dietary intervention is effective in reducing body weight and metabolic syndrome parameters [13]. According to the Obesity Guidelines, an energy deficit of 500–750 kcal per day can result an average weight loss of 0.5–0.75 kg per week, which is 1200–1500 kcal per day for women and 1500–1800 kcal per day for men [14].

3. Exercise

Aerobic exercise on a regular basis improves physical fitness and endurance and in conjunction with diet not only has a positive effect on weight reduction but also reduces the risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular complications by reducing visceral fat, blood pressure, and lipid levels and improving glycemic control [15][16]. As most of the published literature on weight reduction programs lacks long-term follow-ups, it is not known whether weight changes are sustained beyond the intervention periods.

The SUCCESS C (Docetaxel Based Anthracycline Free Adjuvant Treatment Evaluation, as Well as Lifestyle Intervention) phase 3 randomized trial assessed whether physical activity and healthy diets following adjuvant chemotherapy in 3643 women with early-stage breast cancer reduce disease-free survival [17]. Women in the intervention arm had a significant reduction in baseline weight compared with the non-intervention arm. Overall, 1477 women completed the 2-year lifestyle intervention program. An interim analysis showed that women who completed the 2-year lifestyle intervention program had a significantly better disease-free survival than those who did not complete (hazard ratio 0.35) [18]. Several trials are examining whether exercise with or without dietary intervention in obese or healthy weight cancer survivors could improve oncology outcomes (Table 1).

4. Behavior Therapy

Behavior therapy involves the use of various techniques and strategies to replace existing eating and activity behavior with a healthy eating and active lifestyle. It includes tracking eating, calorie intake, and physical activity, modifications of the environment to avoid overeating, the creation of exercise plans, and setting realistic goals, among others [19][20].

5. Drug Therapy

Currently, few drugs are approved for weight loss [21]. The most important of these are glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue liraglutide and semaglutide. In a randomized phase 3 trial, when liraglutide was injected subcutaneously at a dose of 3.0 mg once-daily to 3731 patients as an adjunct to diet and exercise, it was associated with significant weight reduction. For example, after 56 weeks of treatment, 63.2% of treated patients vs. 27.1% with placebo lost at least 5% of their body weight and 33.1% of treated patients vs. 10.6% of the control group lost more than 10% of their body weight [22]. Semaglutide is available as a weekly injection [23]. A handful of preclinical studies suggest their association with thyroid and pancreatic cancer [24][25]. Other suggest that GLP-1 may have a protective effect on a reduction in the growth of certain cancers such as prostate and breast cancer [26][27][28]. Although there is paucity of research of the long-term safety of GLP-1 analogues in cancer survivors, it is a reasonable option in diabetic cancer survivors with excess body weight or those who are normoglycemic but failed other weight reduction measures. Other drugs that have shown efficacy in weight reduction include orlistat, the phentermine–topiramine combination, the bupropion–naltrexone combination, benzphetamine, phendimetrazine, and diethylpropion [21] (Table 1). However, unlike GLP-q analogues, they have more side effects, drug interactions, and several contraindications [21][29].

Table 1. Drugs with US Food Drug Administration (FDA) approved indication for obesity.

| Drug [21][29] | Mechanism of Action | Dose | Weight Change Relative to Placebo | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide | glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP1R) agonists, decreases appetite and delays gastric emptying and gut motility | 2.4 mg once per week subcutaneous injection | 2.4% to 14.9% | abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and pancreatitis (rare) |

| Liraglutide | GLP1R agonists, decreases appetite and delays gastric emptying and gut motility | 3.0 mg per day subcutaneous injection | 2.6% to 8% | diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, constipation, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, pancreatitis, and gallstones |

| Naltrexone SR/bupropion SR | Opioid receptor antagonist/dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor causing appetite suppression | 32 mg/360 mg oral twice daily | dose dependent 1.3% to 6.1% |

headaches, hypertension, sleep disorders, nausea, constipation, vomiting, diarrhea, palpitation, dizziness, tremor, and others |

| Orlistat | Pancreatic lipase inhibitor causing excretion of 30% of ingested trigylcerides in stool | 120 mg 3 times daily | 6.1% to 10.2% | nausea, diarrhea, steatorrhea, abdominal bloating, and hepatitis |

| Phentermine/ topiramate |

Sympathomimetics/anticonvulsant causing appetite suppression | 15 mg/92 mg once daily oral | dose depending 1.2% to 7.8% |

tachycardia, xerostomia, constipation, headache, sleep disorder, anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and cardiovascular event |

| Phendimetrazine | Sympathomimetics causing appetite suppression | Short-term (≤12 weeks) 17.5 to 35 mg 2 or 3 times daily | Not available | hypertension, ischemic events, palpitations, tachycardia, headache, insomnia, overstimulation, psychosis, and others |

6. Weight Reduction Surgery

Weight reduction surgery or bariatric surgery, such as sleeve gastrectomy or adjustable gastric banding, is typically considered in patients with a BMI > 40 kg/m2 or with a BMI of 35–40 kg/m2 with associated comorbid conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea [30]. Ongoing research has deemed that bariatric and related surgeries continue to be safe and will likely be used in the future [31]. The most common and considered to be highly effective forms of surgery used are the sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) [32]. Scant evidence suggests that the benefit of bariatric surgery as a weight reduction intervention is similar in cancer survivors compared with those with no history of cancer [33][34]. A systemic review and meta-analysis of six observational studies involving 51,740 patients demonstrated that bariatric surgery was associated with a 55% reduction in cancer risk. Patients who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity have a 27–59% lower risk of developing cancer than weight- and age-matched controls [35]. The advantages of bariatric surgery might only apply to malignancies linked to obesity, such as those of the breast and endometrium, where the average risk reduction is 38% (p = 0.0001). In contrast, the benefits of bariatric surgery are significantly more moderate (9%) among malignancies unrelated to obesity, such as those of the lung and bladder; this level of risk reduction is comparable to that of individuals who do not undergo bariatric surgery (p = 0.37) [36].

References

- van Gemert, W.A.; Schuit, A.J.; van der Palen, J.; May, A.M.; Iestra, J.A.; Wittink, H.; Peeters, P.H.; Monninkhof, E.M. Effect of weight loss, with or without exercise, on body composition and sex hormones in postmenopausal women: The SHAPE-2 trial. Breast Cancer Res. 2015, 17, 120.

- Campbell, K.L.; Foster-Schubert, K.E.; Alfano, C.M.; Wang, C.C.; Wang, C.Y.; Duggan, C.R.; Mason, C.; Imayama, I.; Kong, A.; Xiao, L.; et al. Reduced-calorie dietary weight loss, exercise, and sex hormones in postmenopausal women: Randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2314–2326.

- Foster-Schubert, K.E.; Alfano, C.M.; Duggan, C.R.; Xiao, L.; Campbell, K.L.; Kong, A.; Bain, C.E.; Wang, C.Y.; Blackburn, G.L.; McTiernan, A. Effect of diet and exercise, alone or combined, on weight and body composition in overweight-to-obese postmenopausal women. Obesity 2012, 20, 1628–1638.

- Imayama, I.; Ulrich, C.M.; Alfano, C.M.; Wang, C.; Xiao, L.; Wener, M.H.; Campbell, K.L.; Duggan, C.; Foster-Schubert, K.E.; Kong, A.; et al. Effects of a caloric restriction weight loss diet and exercise on inflammatory biomarkers in overweight/obese postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 2314–2326.

- Mason, C.; Foster-Schubert, K.E.; Imayama, I.; Kong, A.; Xiao, L.; Bain, C.; Campbell, K.L.; Wang, C.Y.; Duggan, C.R.; Ulrich, C.M.; et al. Dietary weight loss and exercise effects on insulin resistance in postmenopausal women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 366–375.

- Gennari, A.; Amadori, D.; Scarpi, E.; Farolfi, A.; Paradiso, A.; Mangia, A.; Biglia, N.; Gianni, L.; Tienghi, A.; Rocca, A.; et al. Impact of body mass index (BMI) on the prognosis of high-risk early breast cancer (EBC) patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 159, 79–86.

- Ligibel, J.A.; Bohlke, K.; May, A.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Gilchrist, S.C.; Irwin, M.L.; Late, M.; Mansfield, S.; Marshall, T.F.; et al. Exercise, Diet, and Weight Management During Cancer Treatment: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2491–2507.

- Denlinger, C.S.; Ligibel, J.A.; Are, M.; Baker, K.S.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Dizon, D.; Friedman, D.L.; Goldman, M.; Jones, L.; National Comprehensive Cancer Network; et al. Survivorship: Nutrition and weight management, Version 2.2014. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2014, 12, 1396–1406.

- Shaikh, H.; Bradhurst, P.; Ma, L.X.; Tan, S.Y.C.; Egger, S.J.; Vardy, J.L. Body weight management in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 12, CD012110.

- Sacks, F.M.; Bray, G.A.; Carey, V.J.; Smith, S.R.; Ryan, D.H.; Anton, S.D.; McManus, K.; Champagne, C.M.; Bishop, L.M.; Laranjo, N.; et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 859–873.

- Foster, G.D.; Wyatt, H.R.; Hill, J.O.; Makris, A.P.; Rosenbaum, D.L.; Brill, C.; Stein, R.I.; Mohammed, B.S.; Miller, B.; Rader, D.J.; et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 153, 147–157.

- Shai, I.; Schwarzfuchs, D.; Henkin, Y.; Shahar, D.R.; Witkow, S.; Greenberg, I.; Golan, R.; Fraser, D.; Bolotin, A.; Vardi, H.; et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 229–241.

- Bruno, E.; Krogh, V.; Gargano, G.; Grioni, S.; Bellegotti, M.; Venturelli, E.; Panico, S.; Santucci de Magistris, M.; Bonanni, B.; Zagallo, E.; et al. Adherence to Dietary Recommendations after One Year of Intervention in Breast Cancer Women: The DIANA-5 Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2990.

- Jensen, M.D.; Ryan, D.H.; Apovian, C.M.; Ard, J.D.; Comuzzie, A.G.; Donato, K.A.; Hu, F.B.; Hubbard, V.S.; Jakicic, J.M.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 2014, 129 (Suppl. S25), S102–S138.

- Barry, V.W.; Baruth, M.; Beets, M.W.; Durstine, J.L.; Liu, J.; Blair, S.N. Fitness vs. fatness on all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 56, 382–390.

- Gaesser, G.A.; Angadi, S.S.; Sawyer, B.J. Exercise and diet, independent of weight loss, improve cardiometabolic risk profile in overweight and obese individuals. Phys. Sportsmed. 2011, 39, 87–97.

- Rack, B.; Andergassen, U.; Neugebauer, J.; Salmen, J.; Hepp, P.; Sommer, H.; Lichtenegger, W.; Friese, K.; Beckmann, M.W.; Hauner, D.; et al. The German SUCCESS C Study—The First European Lifestyle Study on Breast Cancer. Breast Care 2010, 5, 395–400.

- Janni, W.; Rack, B.; Friedl, T.; Müller, V.; Lorenz, R.; Rezai, M.; Tesch, H.; Heinrich, G.; Andergassen, U.; Harbeck, N. Abstract GS5-03. lifestyle intervention and effect on disease-free survival in early breast cancer pts: Interim analysis from the randomized SUCCESS C study. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, GS5-03.

- Renehan, A.G.; Harvie, M.; Cutress, R.I.; Leitzmann, M.; Pischon, T.; Howell, S.; Howell, A. How to Manage the Obese Patient With Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4284–4294.

- Alamuddin, N.; Bakizada, Z.; Wadden, T.A. Management of Obesity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4295–4305.

- Müller, T.D.; Blüher, M.; Tschöp, M.H.; DiMarchi, R.D. Anti-obesity drug discovery: Advances and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 201–223.

- Pi-Sunyer, X.; Astrup, A.; Fujioka, K.; Greenway, F.; Halpern, A.; Krempf, M.; Lau, D.C.; le Roux, C.W.; Violante Ortiz, R.; Jensen, C.B.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of 3.0 mg of Liraglutide in Weight Management. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 11–22.

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Tran, M.T.D.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 989–1002.

- Egan, A.G.; Blind, E.; Dunder, K.; de Graeff, P.A.; Hummer, B.T.; Bourcier, T.; Rosebraugh, C. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs--FDA and EMA assessment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 794–797.

- Bjerre Knudsen, L.; Madsen, L.W.; Andersen, S.; Almholt, K.; de Boer, A.S.; Drucker, D.J.; Gotfredsen, C.; Egerod, F.L.; Hegelund, A.C.; Jacobsen, H.; et al. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 receptor agonists activate rodent thyroid C-cells causing calcitonin release and C-cell proliferation. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 1473–1486.

- Nomiyama, T.; Kawanami, T.; Irie, S.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Terawaki, Y.; Murase, K.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Nagaishi, R.; Tanabe, M.; Morinaga, H.; et al. Exendin-4, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, attenuates prostate cancer growth. Diabetes 2014, 63, 3891–3905.

- Iwaya, C.; Nomiyama, T.; Komatsu, S.; Kawanami, T.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Horikawa, T.; Yoshinaga, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Exendin-4, a glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonist, attenuates breast cancer growth by inhibiting NF-κB activation. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 4218–4232.

- Ligumsky, H.; Wolf, I.; Israeli, S.; Haimsohn, M.; Ferber, S.; Karasik, A.; Kaufman, B.; Rubinek, T. The peptide-hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 activates cAMP and inhibits growth of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 132, 449–461.

- Yanovski, S.Z.; Yanovski, J.A. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: A systematic and clinical review. JAMA 2014, 311, 74–86.

- Wolfe, B.M.; Kvach, E.; Eckel, R.H. Treatment of Obesity: Weight Loss and Bariatric Surgery. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1844–1855.

- Albaugh, V.L.; Abumrad, N.N. Surgical treatment of obesity. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 158, 135–145.

- Nudel, J.; Sanchez, V.M. Surgical management of obesity. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2019, 92, 206–216.

- Philip, E.J.; Torghabeh, M.H.; Strain, G.W. Bariatric surgery in cancer survivorship: Does a history of cancer affect weight loss outcomes? Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015, 11, 1105–1108.

- Carlsson, L.M.S.; Sjöholm, K.; Jacobson, P.; Andersson-Assarsson, J.C.; Svensson, P.A.; Taube, M.; Carlsson, B.; Peltonen, M. Life Expectancy after Bariatric Surgery in the Swedish Obese Subjects Study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1535–1543.

- Tee, M.C.; Cao, Y.; Warnock, G.L.; Hu, F.B.; Chavarro, J.E. Effect of bariatric surgery on oncologic outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Endosc. 2013, 27, 4449–4456.

- Adams, T.D.; Hunt, S.C. Cancer and obesity: Effect of bariatric surgery. World J. Surg. 2009, 33, 2028–2033.

More

Information

Subjects:

Oncology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

831

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

07 Feb 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No