You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shizuka Uchida | -- | 1316 | 2023-01-30 17:48:03 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1316 | 2023-01-31 07:50:54 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | + 2 word(s) | 1318 | 2023-02-01 01:46:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ilieva, M.; Uchida, S. Obesity-Associated Long Non-Coding RNAs. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40609 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

Ilieva M, Uchida S. Obesity-Associated Long Non-Coding RNAs. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40609. Accessed December 22, 2025.

Ilieva, Mirolyuba, Shizuka Uchida. "Obesity-Associated Long Non-Coding RNAs" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40609 (accessed December 22, 2025).

Ilieva, M., & Uchida, S. (2023, January 30). Obesity-Associated Long Non-Coding RNAs. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40609

Ilieva, Mirolyuba and Shizuka Uchida. "Obesity-Associated Long Non-Coding RNAs." Encyclopedia. Web. 30 January, 2023.

Copy Citation

Due to the increased consumption of high energy and calorie food (e.g., fat, oil, and sugar) coupled with physical inactivity, the number of obese people has increased dramatically worldwide. Because obesity is an underlying cause and risk factor for many diseases (e.g., type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD)), the interest to study obesity-associated lnRNAs has increased.

cardiovascular

genetics

lncRNA

1. Introduction

Cardiometabolic diseases (CMD) account for 31% of all global deaths [1]. These life-long and life-threatening diseases are associated with an unhealthy lifestyle (e.g., obesity, physical inactivity, smoking), leading to diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [2], and more than 56,000 Danes are diagnosed with CVD annually [3]. In CMD (e.g., arrhythmic disorders, cardiomyopathies, Fabry disease, familial hypercholesterolemia, thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections [4]), the genetic inheritance is unavoidable. For example, siblings of patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) have a 40% increase of risk for CVD [5]. Thus, significant efforts have been spent to understand the genetic causes of CMD by genome sequencing the patients suffering from CMD. Through the usages of linkage disequilibrium (LD) and genome-wide association studies (GWAS), a number of loci are found to be associated with CMD [6][7][8][9][10]. Yet, only few are directly in the exons of protein-coding genes, leaving behind the large number of CMD-suspected loci to be unexplained.

The term junk DNA is long gone, and people now know that most of the mammalian genome are transcribed as RNA. Yet only few percent of them correspond to the exons of protein-coding genes, leaving behind the large number of RNAs as non-protein-coding (ncRNAs). These ncRNAs include ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), transfer RNAs (tRNAs), short ncRNAs (e.g., small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs)), microRNAs (miRNAs), and other longer ncRNAs [11]. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are any ncRNAs longer than 200 nucleotides (nt). Because the protein-centered research has not been able to fully elucidate the pathogeneses of CMD nor offer an ultimate cure for CMD, there are growing interests to study lncRNAs in the context of cardiovascular metabolism and CMD. Because lncRNAs occupy a large part of the human genome in comparison to protein-coding genes, increasing evidence suggests that disease-suspected loci based on LD and GWAS are in the loci with lncRNAs [12][13], including the well-known example of the lncRNA, ANRIL [official gene symbol: CDKN2B-AS1 (CDKN2B antisense RNA 1)], which corresponds to the Chr9p21 risk locus for coronary artery disease based on GWAS studies [14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]. Due to the decreased costs of performing both whole genome and transcriptome sequencing (i.e., DNA sequencing (DNA-seq) and RNA-seq, respectively), many lncRNAs have been identified in the disease-suspected loci, which calls for further investigation on how the mutations in lncRNAs themselves affect the susceptibility of each individual to a particular genetic disorder.

2. Obesity-Associated lncRNAs

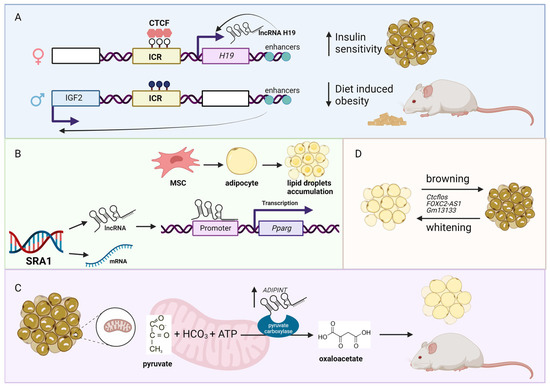

Due to the increased consumption of high energy and calorie food (e.g., fat, oil, and sugar) coupled with physical inactivity, the number of obese people has increased dramatically worldwide in recent years [22][23][24]. Because obesity is an underlying cause and risk factor for many diseases (e.g., type II diabetes, CVD), the interest to study obesity-associated lnRNAs has increased recently. For example, the expression of one of the most well-studied lncRNA, H19 imprinted maternally expressed transcript (H19), is reduced in adipocytes of obese individuals [25]. The functional role of H19 in CMD is well described, which includes negatively regulating hypertrophy [26][27][28] and pyroptosis (a form of cell death initiated by inflammation) [29] in cardiomyocytes. The reduced expression of H19 inversely correlates with body mass index (BMI) in humans. Interestingly, H19 overexpressing mice showed a protective effect against diet-induced obesity and improved insulin sensitivity in brown but not in white adipocytes (Figure 1A). Because BMI is a measure of body fat based on the height and weight of a person, it is used as an indicator of obesity. As such, GWAS and LD studies have been performed to identify BMI-associated loci [30][31]. Not surprisingly, several lncRNAs are shown to be in the BMI-associated loci, such as LncOb rs10487505 variant between BMI and leptin level in pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [32], lncRNA transcript of the transcription factor 7 like 2 (lncRNA-TCF7L2) between BMI and biopolar disorder [33], MCHR2 antisense RNA 1 (MCHR2-AS1) between BMI and psychiatric patients [34], and the hypermethylation of the promoter of the lncRNA, TSPOAP1, SUPT4H1and RNF43 antisense RNA 1 (TSPOAP1-AS1), associated with obesity in overweight and obese Korean individuals [35]. These are just a few examples of BMI-associated lncRNAs reported to date, which most likely increase as more previously published GWAS data are re-analyzed from the standpoint of lncRNAs.

Figure 1. LncRNAs associated with obesity. (A) The H19–IGF2 locus consists of a maternal unmethylated (white lollipops in the image above) imprinting control region (ICR; yellow box). ICR is bound by the insulator protein CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF), which prevents access of the IGF2 promoter (blue box represents the exon from the paternal chromosome) to downstream enhancers. The overexpression of the lncRNA H19 (pink box represents the exon from the maternal chromosome) in mice has a protective effect against diet-induced obesity and increased insulin sensitivity. In the image above, white boxes represent the repressed genes, while black lollipops represent the methylated CpG sites. (B) The SRA1 gene encodes for protein-coding mRNA and lncRNA Sra1. The lncRNA Sra1 functions as a transcription co-activator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparg), which is a regulator of adipocytes differentiation and lipid accumulation. (C) The lncRNA ADIPINT is upregulated in obesity. This lncRNA is responsible for adipocyte size, insulin resistance, and pyruvate carboxylase activity. (D) Several lncRNAs have been identified to be involved in the process of browning and whitening in the adipose tissue, which could serve as potential therapeutic targets. Figure created with BioRender.com (accessed on 10 January 2022).

Obesity is characterized by the increased number of white adipocytes and adipocyte gene expression [36][37]. For example, the whole-body knockout mice of the lncRNA steroid receptor RNA activator 1 (Sra1) are resistant to high fat diet-induced obesity, with decreased epididymal and subcutaneous white adipose tissue (WAT) mass, and increased lean content (i.e., decreased percent of body fat) [38]. Mechanistically, it was shown previously that Sra1 functions as a transcriptional coactivator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparg), which is a master regulator of adipogenesis [39] (Figure 1B). It should be noted that SRA1 encodes for both lncRNA and protein-coding transcripts (https://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Gene/Summary?db=core;g=ENSG00000213523;r=5:140537340-140557677; accessed on 11 January 2023). Another example is adipocyte associated pyruvate carboxylase interacting lncRNA (ADIPINT), whose expression is increased in obesity and linked to fat cell size, adipose insulin resistance, and pyruvate carboxylase activity [40]. Mechanistically, ADIPINT binds to pyruvate carboxylase, which is a mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the ATP-dependent carboxylation of pyruvate to oxaloacetate in order to regulate lipid metabolism (Figure 1C). As adipocytes can be easily isolated and cultured, there are several screening studies to find lncRNAs associated with adipogenesis identifying hundreds of differentially expressed lncRNAs [41][42][43][44][45][46]. Thus, further functional and mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate the functional importance of these adipose-related lncRNAs.

As mentioned above, there are two types of adipocytes: brown and white adipocytes. While white adipocytes store excessive energy as trigycerides, brown adipocytes have significantly more mitochondria than white adipocytes and burn energy to generate heat [47]. Because of the benefits of having more brown adipocytes over white ones for reducing obesity, the interest to study brown adipose tissue (BAT) has increased in recent years [48]. For example, another well-studied lncRNA, X inactive specific transcript (XIST), regulates brown preadipocytes differentiation by directly binding to CCAAT enhancer binding protein alpha (CEBPA, also known as C/EBPα) [49]. Besides BAT, browning of WAT (also called as adipose tissue browning) is gaining attention as a potential therapeutic target to induce thermogenically active adipocytes in WAT to increase energy expenditure and counteract weight gain [50]. During adipose tissue browning, several lncRNAs have been identified and functionally studied, including CCCTC-binding factor (zinc finger protein)-like, opposite strand (Ctcflos) [51], FOXC2 antisense RNA 1 (FOXC2-AS1) [52], and predicted gene 13133 (Gm13133) [53] (Figure 1D). Thus, lncRNAs might hold keys to reduce obesity, thereby reducing CMD.

References

- Yang, T.; Yi, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Ke, S.; Xia, L.; Liu, L. Associations of Dietary Fats with All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality among Patients with Cardiometabolic Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3608.

- Schmidt, H.; Menche, J. The regulatory network architecture of cardiometabolic diseases. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 2–3.

- Association, T.H. HjerteTal.dk. Available online: www.hjertetal.dk (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Musunuru, K.; Hershberger, R.E.; Day, S.M.; Klinedinst, N.J.; Landstrom, A.P.; Parikh, V.N.; Prakash, S.; Semsarian, C.; Sturm, A.C.; American Heart Association Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; et al. Genetic Testing for Inherited Cardiovascular Diseases: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, e000067.

- Kolber, M.R.; Scrimshaw, C. Family history of cardiovascular disease. Can. Fam. Physician 2014, 60, 1016.

- Arvanitis, M.; Tampakakis, E.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Auton, A.; 23andMe Research Team; Dutta, D.; Glavaris, S.; Keramati, A.; Chatterjee, N.; et al. Genome-wide association and multi-omic analyses reveal ACTN2 as a gene linked to heart failure. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1122.

- Benn, M.; Nordestgaard, B.G. From genome-wide association studies to Mendelian randomization: Novel opportunities for understanding cardiovascular disease causality, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1192–1208.

- Kessler, T.; Vilne, B.; Schunkert, H. The impact of genome-wide association studies on the pathophysiology and therapy of cardiovascular disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 688–701.

- Cheng, S.; Grow, M.A.; Pallaud, C.; Klitz, W.; Erlich, H.A.; Visvikis, S.; Chen, J.J.; Pullinger, C.R.; Malloy, M.J.; Siest, G.; et al. A multilocus genotyping assay for candidate markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Genome Res. 1999, 9, 936–949.

- Aragam, K.G.; Jiang, T.; Goel, A.; Kanoni, S.; Wolford, B.N.; Atri, D.S.; Weeks, E.M.; Wang, M.; Hindy, G.; Zhou, W.; et al. Discovery and systematic characterization of risk variants and genes for coronary artery disease in over a million participants. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 1803–1815.

- Uchida, S.; Adams, J.C. Physiological roles of non-coding RNAs. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019, 317, C1–C2.

- Nurnberg, S.T.; Zhang, H.; Hand, N.J.; Bauer, R.C.; Saleheen, D.; Reilly, M.P.; Rader, D.J. From Loci to Biology: Functional Genomics of Genome-Wide Association for Coronary Disease. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 586–606.

- Mirza, A.H.; Kaur, S.; Brorsson, C.A.; Pociot, F. Effects of GWAS-associated genetic variants on lncRNAs within IBD and T1D candidate loci. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105723.

- Holdt, L.M.; Teupser, D. Long Noncoding RNA ANRIL: Lnc-ing Genetic Variation at the Chromosome 9p21 Locus to Molecular Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 145.

- Holdt, L.M.; Beutner, F.; Scholz, M.; Gielen, S.; Gabel, G.; Bergert, H.; Schuler, G.; Thiery, J.; Teupser, D. ANRIL expression is associated with atherosclerosis risk at chromosome 9p21. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 620–627.

- Matarin, M.; Brown, W.M.; Singleton, A.; Hardy, J.A.; Meschia, J.F. Whole genome analyses suggest ischemic stroke and heart disease share an association with polymorphisms on chromosome 9p21. Stroke 2008, 39, 1586–1589.

- Larson, M.G.; Atwood, L.D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Cupples, L.A.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Fox, C.S.; Govindaraju, D.R.; Guo, C.Y.; Heard-Costa, N.L.; Hwang, S.J.; et al. Framingham Heart Study 100K project: Genome-wide associations for cardiovascular disease outcomes. BMC Med. Genet. 2007, 8, S5.

- Samani, N.J.; Erdmann, J.; Hall, A.S.; Hengstenberg, C.; Mangino, M.; Mayer, B.; Dixon, R.J.; Meitinger, T.; Braund, P.; Wichmann, H.E.; et al. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 443–453.

- The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3000 shared controls. Nature 2007, 447, 661–678.

- McPherson, R.; Pertsemlidis, A.; Kavaslar, N.; Stewart, A.; Roberts, R.; Cox, D.R.; Hinds, D.A.; Pennacchio, L.A.; Tybjaerg-Hansen, A.; Folsom, A.R.; et al. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science 2007, 316, 1488–1491.

- Helgadottir, A.; Thorleifsson, G.; Manolescu, A.; Gretarsdottir, S.; Blondal, T.; Jonasdottir, A.; Jonasdottir, A.; Sigurdsson, A.; Baker, A.; Palsson, A.; et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science 2007, 316, 1491–1493.

- Fox, A.; Feng, W.; Asal, V. What is driving global obesity trends? Globalization or “modernization”? Glob. Health 2019, 15, 32.

- Romieu, I.; Dossus, L.; Barquera, S.; Blottiere, H.M.; Franks, P.W.; Gunter, M.; Hwalla, N.; Hursting, S.D.; Leitzmann, M.; Margetts, B.; et al. Energy balance and obesity: What are the main drivers? Cancer Causes Control 2017, 28, 247–258.

- Shook, R.P.; Blair, S.N.; Duperly, J.; Hand, G.A.; Matsudo, S.M.; Slavin, J.L. What is Causing the Worldwide Rise in Body Weight? Eur. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 136–144.

- Schmidt, E.; Dhaouadi, I.; Gaziano, I.; Oliverio, M.; Klemm, P.; Awazawa, M.; Mitterer, G.; Fernandez-Rebollo, E.; Pradas-Juni, M.; Wagner, W.; et al. LincRNA H19 protects from dietary obesity by constraining expression of monoallelic genes in brown fat. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3622.

- Viereck, J.; Buhrke, A.; Foinquinos, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Kleeberger, J.A.; Xiao, K.; Janssen-Peters, H.; Batkai, S.; Ramanujam, D.; Kraft, T.; et al. Targeting muscle-enriched long non-coding RNA H19 reverses pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3462–3474.

- Hobuss, L.; Foinquinos, A.; Jung, M.; Kenneweg, F.; Xiao, K.; Wang, Y.; Zimmer, K.; Remke, J.; Just, A.; Nowak, J.; et al. Pleiotropic cardiac functions controlled by ischemia-induced lncRNA H19. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 146, 43–59.

- Liu, L.; An, X.; Li, Z.; Song, Y.; Li, L.; Zuo, S.; Liu, N.; Yang, G.; Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; et al. The H19 long noncoding RNA is a novel negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016, 111, 56–65.

- Han, Y.; Dong, B.; Chen, M.; Yao, C. LncRNA H19 suppresses pyroptosis of cardiomyocytes to attenuate myocardial infarction in a PBX3/CYP1B1-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 1387–1400.

- Yengo, L.; Sidorenko, J.; Kemper, K.E.; Zheng, Z.; Wood, A.R.; Weedon, M.N.; Frayling, T.M.; Hirschhorn, J.; Yang, J.; Visscher, P.M.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in approximately 700,000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 3641–3649.

- Locke, A.E.; Kahali, B.; Berndt, S.I.; Justice, A.E.; Pers, T.H.; Day, F.R.; Powell, C.; Vedantam, S.; Buchkovich, M.L.; Yang, J.; et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015, 518, 197–206.

- Manco, M.; Crudele, A.; Mosca, A.; Caccamo, R.; Braghini, M.R.; De Vito, R.; Alterio, A.; Pizzolante, F.; De Peppo, F.; Alisi, A. LncOb rs10487505 variant is associated with leptin levels in pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 92, 1737–1743.

- Liu, D.; Nguyen, T.T.L.; Gao, H.; Huang, H.; Kim, D.C.; Sharp, B.; Ye, Z.; Lee, J.H.; Coombes, B.J.; Ordog, T.; et al. TCF7L2 lncRNA: A link between bipolar disorder and body mass index through glucocorticoid signaling. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 7454–7464.

- Delacretaz, A.; Preisig, M.; Vandenberghe, F.; Saigi Morgui, N.; Quteineh, L.; Choong, E.; Gholam-Rezaee, M.; Kutalik, Z.; Magistretti, P.; Aubry, J.M.; et al. Influence of MCHR2 and MCHR2-AS1 Genetic Polymorphisms on Body Mass Index in Psychiatric Patients and In Population-Based Subjects with Present or Past Atypical Depression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139155.

- Yim, N.H.; Cha, M.H.; Kim, M.S. Hypermethylation of the TSPOAP1-AS1 Promoter May Be Associated with Obesity in Overweight/Obese Korean Subjects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3307.

- Sam, S.; Mazzone, T. Adipose tissue changes in obesity and the impact on metabolic function. Transl. Res. 2014, 164, 284–292.

- Attie, A.D.; Scherer, P.E. Adipocyte metabolism and obesity. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, S395–S399.

- Liu, S.; Sheng, L.; Miao, H.; Saunders, T.L.; MacDougald, O.A.; Koenig, R.J.; Xu, B. SRA gene knockout protects against diet-induced obesity and improves glucose tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 13000–13009.

- Lanz, R.B.; McKenna, N.J.; Onate, S.A.; Albrecht, U.; Wong, J.; Tsai, S.Y.; Tsai, M.J.; O’Malley, B.W. A steroid receptor coactivator, SRA, functions as an RNA and is present in an SRC-1 complex. Cell 1999, 97, 17–27.

- Kerr, A.G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, N.; Kwok, K.H.M.; Jalkanen, J.; Ludzki, A.; Lecoutre, S.; Langin, D.; Bergo, M.O.; Dahlman, I.; et al. The long noncoding RNA ADIPINT regulates human adipocyte metabolism via pyruvate carboxylase. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2958.

- Alvarez-Dominguez, J.R.; Winther, S.; Hansen, J.B.; Lodish, H.F.; Knoll, M. An adipose lncRAP2-Igf2bp2 complex enhances adipogenesis and energy expenditure by stabilizing target mRNAs. iScience 2022, 25, 103680.

- Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Zhou, X.; Hu, S.; Ge, L.; Sun, J.; Li, P.; Long, K.; Jin, L.; Tang, Q.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of mRNA and lncRNA Transcriptomes Reveals the Differentially Hypoxic Response of Preadipocytes During Adipogenesis. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 845.

- Ding, C.; Lim, Y.C.; Chia, S.Y.; Walet, A.C.E.; Xu, S.; Lo, K.A.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, D.; Shan, Z.; Chen, Q.; et al. De novo reconstruction of human adipose transcriptome reveals conserved lncRNAs as regulators of brown adipogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1329.

- Lo, K.A.; Huang, S.; Walet, A.C.E.; Zhang, Z.C.; Leow, M.K.; Liu, M.; Sun, L. Adipocyte Long-Noncoding RNA Transcriptome Analysis of Obese Mice Identified Lnc-Leptin, Which Regulates Leptin. Diabetes 2018, 67, 1045–1056.

- Bai, Z.; Chai, X.R.; Yoon, M.J.; Kim, H.J.; Lo, K.A.; Zhang, Z.C.; Xu, D.; Siang, D.T.C.; Walet, A.C.E.; Xu, S.H.; et al. Dynamic transcriptome changes during adipose tissue energy expenditure reveal critical roles for long noncoding RNA regulators. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2002176.

- Sun, L.; Goff, L.A.; Trapnell, C.; Alexander, R.; Lo, K.A.; Hacisuleyman, E.; Sauvageau, M.; Tazon-Vega, B.; Kelley, D.R.; Hendrickson, D.G.; et al. Long noncoding RNAs regulate adipogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3387–3392.

- Saely, C.H.; Geiger, K.; Drexel, H. Brown versus white adipose tissue: A mini-review. Gerontology 2012, 58, 15–23.

- Samuelson, I.; Vidal-Puig, A. Studying Brown Adipose Tissue in a Human in vitro Context. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 629.

- Wu, C.; Fang, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Ma, X.; Xue, Y.; et al. Long noncoding RNA XIST regulates brown preadipocytes differentiation and combats high-fat diet induced obesity by targeting C/EBPalpha. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 6.

- Herz, C.T.; Kiefer, F.W. Adipose tissue browning in mice and humans. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 241, R97–R109.

- Gupta, A.; Shamsi, F.; Altemose, N.; Dorlhiac, G.F.; Cypess, A.M.; White, A.P.; Yosef, N.; Patti, M.E.; Tseng, Y.H.; Streets, A. Characterization of transcript enrichment and detection bias in single-nucleus RNA-seq for mapping of distinct human adipocyte lineages. Genome Res. 2022, 32, 242–257.

- Wang, Y.; Hua, S.; Cui, X.; Cao, Y.; Wen, J.; Chi, X.; Ji, C.; Pang, L.; You, L. The Effect of FOXC2-AS1 on White Adipocyte Browning and the Possible Regulatory Mechanism. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 565483.

- You, L.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wen, J.; Xie, K.; Tang, R.; et al. GM13133 is a negative regulator in mouse white adipocytes differentiation and drives the characteristics of brown adipocytes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 313–324.

More

Information

Subjects:

Endocrinology & Metabolism

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

849

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 Feb 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No