Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brij Pal Singh | -- | 1978 | 2023-01-30 07:49:01 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | + 2 word(s) | 1980 | 2023-01-30 08:49:34 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Singh, B.P.; Rohit, R.; Manju, K.M.; Sharma, R.; Bhushan, B.; Ghosh, S.; Goel, G. Antimicrobial Actions of Food-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40551 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Singh BP, Rohit R, Manju KM, Sharma R, Bhushan B, Ghosh S, et al. Antimicrobial Actions of Food-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40551. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Singh, Brij Pal, Rohit Rohit, K. M. Manju, Rohit Sharma, Bharat Bhushan, Sougata Ghosh, Gunjan Goel. "Antimicrobial Actions of Food-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40551 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Singh, B.P., Rohit, R., Manju, K.M., Sharma, R., Bhushan, B., Ghosh, S., & Goel, G. (2023, January 30). Antimicrobial Actions of Food-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40551

Singh, Brij Pal, et al. "Antimicrobial Actions of Food-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides." Encyclopedia. Web. 30 January, 2023.

Copy Citation

Microbial food safety has garnered a lot of attention due to worldwide expansion of the food industry and processed food products. This has driven the development of novel preservation methods over traditional ones. Food-derived antimicrobial peptides (F-AMPs), produced by the proteolytic degradation of food proteins, are emerging as pragmatic alternatives for extension of the shelf-life of food products. The main benefits of F-AMPs are their wide spectrum antimicrobial efficacy and low propensity for the development of antibiotic resistance.

antimicrobial peptides

food safety

nano-conjugation

1. Introduction

Maintaining life and nurturing good health depends on the availability of safe and nutritious food. Microbial food safety is therefore, the most crucial and challenging issue, along with balanced nutrition due to increased export of processed foods globally. The main factor contributing to food deterioration in both processed and unprocessed foods is microbial contamination. Unsafe food carrying bacteria, viruses, parasites, or chemicals causes more than 200 ailments, from cancer to diarrhea. According to the estimates, 600 million people worldwide (i.e., nearly one in ten) get sick after eating contaminated food, and more than 400,000 people die each year [1]. Additionally, it is anticipated that the annual cost of treating food-borne illnesses will be US$ 15 billion and that the overall cost is US$ 95.2 billion in productivity losses caused by foodborne illnesses, particularly in low- and middle-income nations [2][3]. Foods can become contaminated by microbes at many points during production, processing, and packaging. Due to this damage and spoilage, around 15 to 25 % of perishable food items remain unsafe for human consumption in the retail setting [4][5][6]. Moreover, increasing trends of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in food-borne pathogens are one of the major factors limiting the safety and quality of processed foods. A number of these pathogenic bacteria are continuously acquiring AMR traits, posing a serious threat to human health and wellbeing [7][8]. Therefore, efforts are now being made to increase shelf life of processed food items while maintaining their safety, nutritional value, and sensory attributes through natural methods of preservation.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are presently being tested to enhance the quality and safety of food products. AMPs are low-molecular-weight proteins with antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal activities. However, it is important to understand the difference between AMPs and food-derived antimicrobial peptides (F-AMPs) before looking into further details. While AMPs are host-defense peptides produced by many unicellular or multicellular organisms as a first line of defense against invading pathogens, the F-AMPs are peptides produced from food proteins in-vivo by gastrointestinal enzymes, or in-vitro through enzymatic hydrolysis, or during fermentation of food. The F-AMPs are essentially encoded into various food proteins and when released they primarily exert their antibacterial effects by disrupting bacterial cell membranes [9][10][11]. The basic structure of AMPs are abundant hydrophilic amino acids at the N-terminus, while non-polar hydrophobic amino acids are abundant at the C-terminus, which are crucial for AMPs to bind to bacterial cell membranes and alter their permeability to elicit antibacterial action [12]. AMPs have a number of benefits over conventional antibiotics, including the ability to positively influence the human immune response, a limited establishment of resistance, and broad-spectrum antibiofilm activity [13].

Despite being investigated as potential bio-preservatives, the effectiveness of F-AMPs has always been a concern due to their instability during food processing and storage, which may result in lower antimicrobial activity. Therefore, nano-conjugated F-AMPs have emerged as potential candidates against these constraints, along with an enhancement of their delivery through foods [14]. Moreover, the recent applications of these nano-conjugated AMPs in active packaging are also being explored, whereby the controlled release of AMPs enhances their efficacy and increases shelf life of coated, packaged food products. Antimicrobial packaging is a cutting-edge approach against proliferation of specific spoilage or pathogenic microorganisms.

2. Antimicrobial Actions of F-AMPs

Most of the food borne pathogens exist in two phases of growth, the planktonic phase and as biofilms. AMPs have been tested for their efficacy against both types of growth behavior. The mechanisms of action of AMPs differ in these stages of growth.

2.1. AMPs Action against Planktonic Cells

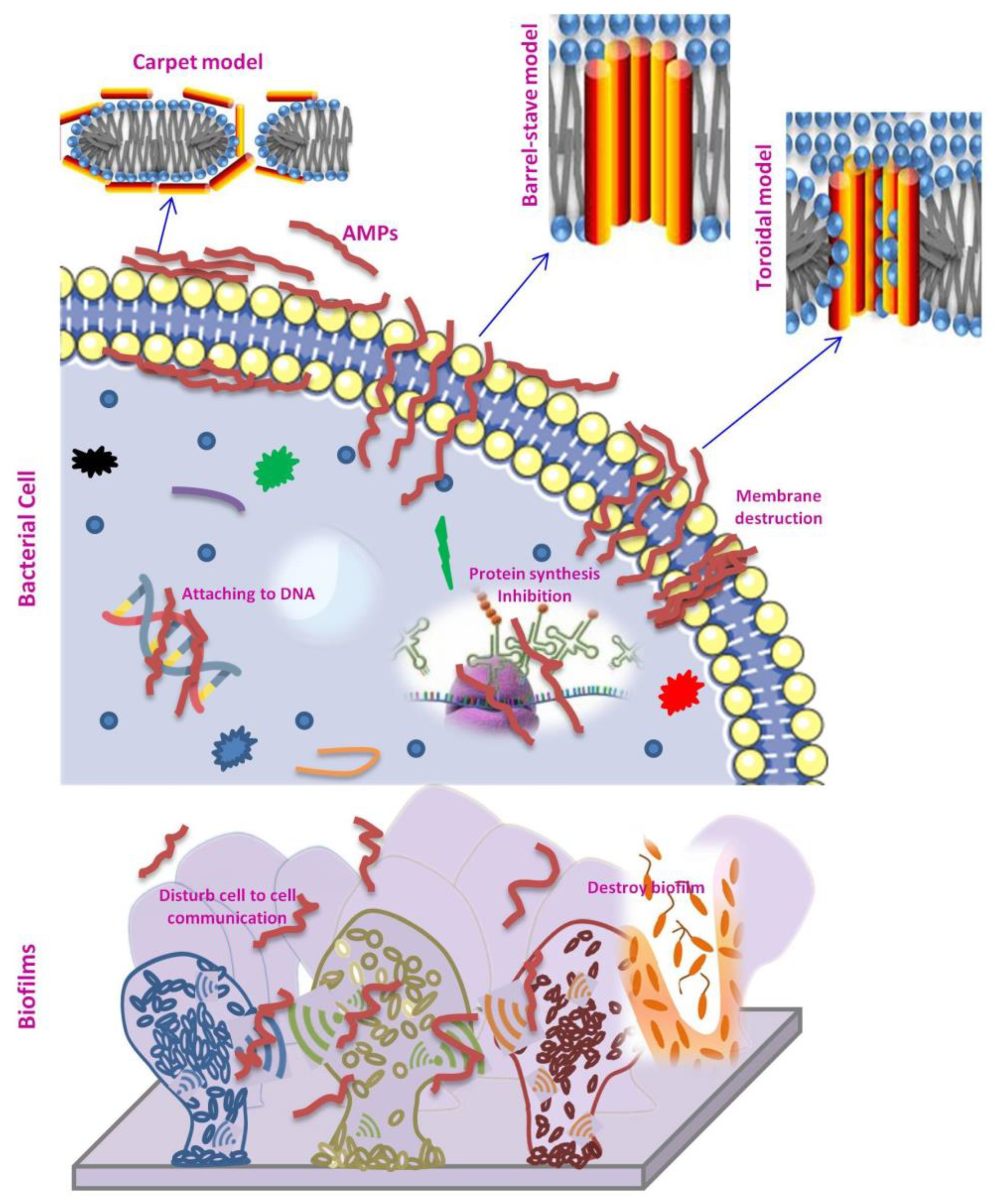

Although the exact mechanism of action of AMPs is still unknown, it has been suggested that these peptides interact on microbial cell membranes to cause pore formation and cell disintegration. Recent studies have however, identified additional potential mechanisms of action, such as interaction with particular intracellular targets, interference with bacterial metabolism, inhibition of protein and nucleic acid synthesis, disruption of the synthesis of cellular components, and inhibition of enzyme activity (Figure 1) [15]. Unlike antibiotics, these broad-spectrum activities of AMPs, therefore, prevent bacteria from developing resistance. In general, the AMPs share two physical characteristics: a cationic charge and a large number of hydrophobic residues. The majority of AMPs have secondary cationic amphipathic structures like α-helices and β-sheets, that enable them to interact with anionic bacterial membranes only through electrostatic interactions [16]. Moreover, the antibacterial activity of some specific amino acid residues in AMPs is largely correlated; for instance, AMPs with Arg and Val invariably have a significant antimicrobial impact because of their greater electrostatic film adsorption. Similarly, AMPs enriched with Pro are crucial for fungicidal activity as they regulate the mode of action of AMPs by crossing the cell membrane and interacting with intracellular macromolecules [12].

Figure 1. Mode of action of F-AMPs against bacterial cells and biofilms.

Cell membrane integrity is disrupted by the amphipathic nature of AMPs combined with the cationic nature of peptides. The negatively charged components of the cell membrane interact with the hydrophilic and cationic peptides. On the outer surfaces of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, teichoic acid and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) are present. Each of these compounds imparts a net negative charge to the surface, enabling the first electrostatic interaction with cationic AMPs. The hydrophobic domain of peptides, on the other hand, interact with the lipid bilayer to change its integrity. This causes the cell membrane to disintegrate, resulting in bacterial death [17][18][19][20]. The interaction of AMPs with cell membrane components could be divided into two categories, specific and non-specific interactions, depending on the requirements of cell surface receptors. For instance, Casein201, a human milk peptide, inhibited the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Yersinia enterocolitica by disintegrating cytoplasmic structures and altering bacterial cell envelopes through non-specific electrostatic interactions [21]. These interactions are brought about by electrostatic contacts between the positively charged peptide moieties and the negatively charged components of the bacterial outer membranes; these electrostatic interactions do not need the presence of specific receptors at the bacterial membrane. Furthermore, peptides penetrate gram-negative bacteria’s outer membrane via hydrophobic interactions; the peptide may adopt a spatial conformation that facilitates the formation of a peptide–membrane complex, causing the outer membrane architecture to be disrupted, allowing additional peptide molecules to pass through [15]. Nisin, bacteriocins that preferentially bind to lipid II in the first step of its mode of action, is the first known receptor-mediated AMP which can be categorized as having specific interactions. At even nanomolar concentrations, this connection inhibits cell wall synthesis and causes pore formation, resulting in membrane permeabilization [22].

Generally, after the initial interactions, the AMPs typically build up at the surface and, after reaching a threshold level, they self-assemble on the bacterial membrane. At this stage, membrane active mechanisms of AMPs are demonstrated through three models: barrel-stave, toroidal, and carpet (Figure 1). The interactions of the hydrophilic portions of peptides cause AMP molecules to adsorb through the membrane surface and self-assemble in the barrel-stave model. The peptide bulk rotates perpendicularly to the plasma membrane when the laterally accumulated peptide monomers reach a specific density on the membrane. Finally, the peptide bulks are positioned along the bilayer hydrophobic portion, forming a channel with the hydrophilic surface facing inwards. Peptides are inserted perpendicularly in the bilayer in the toroidal model, similar to the barrel-stave model, but instead of peptide–peptide interactions, they create a peptide–lipid complex. This peptide-lipid conformation causes a local membrane curvature that is partially surrounded by peptides and partly by phospholipid head groups, resulting in the creation of a ‘toroidal pore’. The net arrangement of a bilayer in this model is differing from the barrel-stave in that the hydrophobic and hydrophilic arrangement of the lipids are preserved in the barrel-stave but disturbed in the toroidal model. This gives the lipid tail and lipid head groups different surfaces to interact with. Because the pores disintegrate quickly, some peptides translocate to the inner cytoplasmic leaflet, where they reach the cytoplasm and may target intracellular components. AMPs, on the other hand, are bonded parallel to the membrane surface in the carpet model. The peptides accumulate until a threshold concentration, at which they reorient towards the inside of the membranes and form micelles with a hydrophobic center that results in membrane breakdown. The carpet model does not require precise peptide–peptide interactions between membrane-bound peptide monomers, nor does it require that the peptide be inserted into the hydrophobic core to produce transmembrane channels or unique peptide structures [19][22][23][24][25].

Beside membrane-active mechanisms, various AMPs have recently been identified that target essential cell components and cellular activities, resulting in bacterial death. These AMPs pass through the cell membrane without disturbing it, and then interact with intracellular targets to obstruct vital cellular activities. The proline-rich peptides have intracellular activity through suppression of bacterial protein synthesis. For example, Bac7 from bovines interacts with the ribosome and inhibits translation by impeding the transition from the initiation to the elongation phase [22][26]. The peptide αs165-181, which is derived from αs2-casein of ovine milk, exerts antibacterial effect through destruction of the bacterial cell membrane and attachment to their genomic DNA [27]. AMPs, like conventional antibiotics such as penicillin, are also reported to block cell wall synthesis. However, AMPs are interacting with essential precursor molecules that are essential for cell wall synthesis, rather than binding with particular proteins involved in the synthesis of cell wall components as reported for antibiotics [19].

2.2. AMPs against Bacterial Biofilms

Pathogens contaminate food during processing conditions, whereby the pathogens come into contact with the surface of food itself and the related equipment. After adhering to the surface, most of the pathogens form biofilm on solid or viscous food surfaces and abiotic surfaces of equipment. A biofilm is formed via multiple processes, starting with adherence to biotic or abiotic surfaces, which leads to the establishment of a micro-colony, which then gives rise to three-dimensional structures, and finally, elimination after maturation of biofilms. Microorganisms are embedded in a biofilm by a matrix of exopolymeric substances (EPS) that acts as a barrier and make the cells resistant to a variety of hostile environments such as sanitizers, disinfectants, antibiotics, and other hygienic conditions, posing a challenge to the food industry in maintaining quality and safety of foods [8][28][29].

The antibiofilm effects of AMPs have been studied in recent years; Batoni and coworkers proposed two modes of action to explain the antibiofilm activity of AMPs, namely classical and non-classical mechanisms. The classic mode of action relies on known bactericidal effects of AMPs on planktonic bacteria that limit their ability to form biofilms. The non-classical process is linked to an AMP activity that targets the biofilm fundamental characteristics [30]. AMPs may block cell–cell interaction by binding to the bacterial surface, limiting the bacterial adherence to the biomaterial surface, interfering with cell communication signals, or promoting the down regulation of genes required for biofilms development [22]. Biofilms’ cell signaling systems can also be disrupted by AMPs (Figure 1). The peptides reduce biofilm development by inhibiting RNA synthesis and blocking the synthesis of guanosine tetraphosphate and pentaphosphate via the enzymes RelA and SpoT. Additionally, AMPs can function as quorum sensing inhibitors (QSI), which impede cell-to-cell communication and prevent the formation of new biofilms. For instance, Listeria monocytogenes biofilm development was reduced using the bacteriocins, lactocin AL705, which inhibited quorum sensing (QS) by inactivating the signal molecule autoinducer-2 (AI-2) [31]. The QS, a highly organized cell-to-cell signaling communication system, controls bacterial population density by regulating the synthesis of virulence factors in response to variations in bacterial population density [32]. The signal molecules such as autoinducer, N-Acetylated-l-homoserine lactones (AHLs) and peptide-based signal molecules play the key role in QS [33].

References

- WHO. Food Safety. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Gizaw, Z. Public Health Risks Related to Food Safety Issues in the Food Market: A Systematic Literature Review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 68.

- León Madrazo, A.; Segura Campos, M.R. Review of Antimicrobial Peptides as Promoters of Food Safety: Limitations and Possibilities within the Food Industry. J. Food Saf. 2020, 40, e12854.

- FAO. Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO, Ed.; The state of food and agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-92-5-131789-1.

- Agrillo, B.; Balestrieri, M.; Gogliettino, M.; Palmieri, G.; Moretta, R.; Proroga, Y.T.R.; Rea, I.; Cornacchia, A.; Capuano, F.; Smaldone, G.; et al. Functionalized Polymeric Materials with Bio-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides for “Active” Packaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 601.

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Forough, M.; Amjadi, S.; Javan Kouzegaran, V.; Almasi, H.; Garavand, F.; Zargar, M. Plant Protein-Based Nanocomposite Films: A Review on the Used Nanomaterials, Characteristics, and Food Packaging Applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022; in press.

- Sharma, C.; Rokana, N.; Chandra, M.; Singh, B.P.; Gulhane, R.D.; Gill, J.P.S.; Ray, P.; Puniya, A.K.; Panwar, H. Antimicrobial Resistance: Its Surveillance, Impact, and Alternative Management Strategies in Dairy Animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 4, 237.

- Singh, B.P.; Ghosh, S.; Chauhan, A. Development, Dynamics and Control of Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacterial Biofilms: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1983–1993.

- Singh, B.P.; Vij, S.; Hati, S.; Singh, D.; Kumari, P.; Minj, J. Antimicrobial Activity of Bioactive Peptides Derived from Fermentation of Soy Milk by Lactobacillus Plantarum C2 against Common Foodborne Pathogens. Int. J. Ferment. Foods 2015, 4, 91.

- Singh, B.P.; Vij, S.; Hati, S. Functional Significance of Bioactive Peptides Derived from Soybean. Peptides 2014, 54, 171–179.

- Singh, B.P.; Bangar, S.P.; Alblooshi, M.; Ajayi, F.F.; Mudgil, P.; Maqsood, S. Plant-Derived Proteins as a Sustainable Source of Bioactive Peptides: Recent Research Updates on Emerging Production Methods, Bioactivities, and Potential Application. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022; in press.

- Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, Z.; Lin, H.; Yang, K. Overview of the Preparation Method, Structure and Function, and Application of Natural Peptides and Polypeptides. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113493.

- Magana, M.; Pushpanathan, M.; Santos, A.L.; Leanse, L.; Fernandez, M.; Ioannidis, A.; Giulianotti, M.A.; Apidianakis, Y.; Bradfute, S.; Ferguson, A.L.; et al. The Value of Antimicrobial Peptides in the Age of Resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e216–e230.

- Liu, Y.; Sameen, D.E.; Ahmed, S.; Dai, J.; Qin, W. Antimicrobial Peptides and Their Application in Food Packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 471–483.

- Santos, J.C.P.; Sousa, R.C.S.; Otoni, C.G.; Moraes, A.R.F.; Souza, V.G.L.; Medeiros, E.A.A.; Espitia, P.J.P.; Pires, A.C.S.; Coimbra, J.S.R.; Soares, N.F.F. Nisin and Other Antimicrobial Peptides: Production, Mechanisms of Action, and Application in Active Food Packaging. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 48, 179–194.

- Sibel Akalın, A. Dairy-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides: Action Mechanisms, Pharmaceutical Uses and Production Proposals. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 36, 79–95.

- Daliri, E.B.-M.; Lee, B.H.; Oh, D.H. Current Trends and Perspectives of Bioactive Peptides. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2273–2284.

- Ahmed, T.A.E.; Hammami, R. Recent Insights into Structure–Function Relationships of Antimicrobial Peptides. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12546.

- Kumar, P.; Kizhakkedathu, J.N.; Straus, S.K. Antimicrobial Peptides: Diversity, Mechanism of Action and Strategies to Improve the Activity and Biocompatibility In Vivo. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 4.

- Ghosh, C.; Sarkar, P.; Issa, R.; Haldar, J. Alternatives to Conventional Antibiotics in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 323–338.

- Zhang, F.; Cui, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, T. Antimicrobial Activity and Mechanism of the Human Milk-Sourced Peptide Casein201. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 485, 698–704.

- Erdem Büyükkiraz, M.; Kesmen, Z. Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs): A Promising Class of Antimicrobial Compounds. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 1573–1596.

- Singh, A.; Duche, R.T.; Wandhare, A.G.; Sian, J.K.; Singh, B.P.; Sihag, M.K.; Singh, K.S.; Sangwan, V.; Talan, S.; Panwar, H. Milk-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides: Overview, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 15, 44–62.

- López-Meza, J.E.; Aguilar, A.O.-Z.J.A.; Loeza-Lara, P.D. Antimicrobial Peptides: Diversity and Perspectives for Their Biomedical Application; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-953-307-514-3.

- Hazam, P.K.; Goyal, R.; Ramakrishnan, V. Peptide Based Antimicrobials: Design Strategies and Therapeutic Potential. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2019, 142, 10–22.

- Gagnon, M.G.; Roy, R.N.; Lomakin, I.B.; Florin, T.; Mankin, A.S.; Steitz, T.A. Structures of Proline-Rich Peptides Bound to the Ribosome Reveal a Common Mechanism of Protein Synthesis Inhibition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 2439–2450.

- Omidbakhsh Amiri, E.; Farmani, J.; Raftani Amiri, Z.; Dehestani, A.; Mohseni, M. Antimicrobial Activity, Environmental Sensitivity, Mechanism of Action, and Food Application of As165-181 Peptide. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 358, 109403.

- Nahar, S.; Mizan, M.F.R.; Ha, A.J.; Ha, S.-D. Advances and Future Prospects of Enzyme-Based Biofilm Prevention Approaches in the Food Industry. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 1484–1502.

- Abebe, G.M. The Role of Bacterial Biofilm in Antibiotic Resistance and Food Contamination. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, e1705814.

- Batoni, G.; Maisetta, G.; Esin, S. Antimicrobial Peptides and Their Interaction with Biofilms of Medically Relevant Bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 1044–1060.

- Melian, C.; Segli, F.; Gonzalez, R.; Vignolo, G.; Castellano, P. Lactocin AL705 as Quorum Sensing Inhibitor to Control Listeria Monocytogenes Biofilm Formation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 911–920.

- Shang, D.; Han, X.; Du, W.; Kou, Z.; Jiang, F. Trp-Containing Antibacterial Peptides Impair Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Development in Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Exhibit Synergistic Effects With Antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 611009.

- Singh, B.N.; Prateeksha; Upreti, D.K.; Singh, B.R.; Defoirdt, T.; Gupta, V.K.; De Souza, A.O.; Singh, H.B.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; et al. Bactericidal, Quorum Quenching and Anti-Biofilm Nanofactories: A New Niche for Nanotechnologists. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 525–540.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

810

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

30 Jan 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No