Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | George Sourvinos | -- | 3056 | 2023-01-13 22:15:12 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 3056 | 2023-01-16 02:53:21 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Dimitraki, M.G.; Sourvinos, G. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Cancers. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40170 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Dimitraki MG, Sourvinos G. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Cancers. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40170. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Dimitraki, Maria Georgia, George Sourvinos. "Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Cancers" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40170 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Dimitraki, M.G., & Sourvinos, G. (2023, January 13). Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Cancers. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40170

Dimitraki, Maria Georgia and George Sourvinos. "Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Cancers." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 January, 2023.

Copy Citation

Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV), the sole member of Polyomavirus associated with oncogenesis in humans, is the major causative factor of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), a rare, neuroendocrine neoplasia of the skin. Many aspects of MCPyV biology and oncogenic mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Merkel cell polyomavirus

MCPyV

Merkel cell carcinoma

1. Introduction

Cancer is a group of diseases with a major global health impact, estimated to become the leading cause of premature death in this century, according to GLOBOCAN 2020 [1]. The emergence of cancer is primarily linked to both genetic predisposition and environmental factors [2]. Nevertheless, recent studies have identified some infectious agents as risk factors of cancer development in humans [3]. According to data from 2018, infection-attributable cancers represented the third leading cause of cancer development (2.2 million cases) [4], following smoking and diet [5]. Additionally, infection-related cancer cases have mostly been reported in the developing parts of the world [4]. Most of those oncogenic agents are characterized as Group I human carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and they include viruses, bacteria, and parasites [6][7][8]. Recent advances in the fields of molecular biology have shed light on the correlation between fluke infections and cancer formation and, therefore, have provided valuable insights into the molecular basis of oncogenesis [9]. Generally, infectious agents seem to be able to cause malignant transformation via direct and indirect mechanisms: persistent infection that eventually leads to inflammation, DNA alternations and cell damage, irregular oncogene expression, and immunologic recognition disruption [7][8][9]. Amongst the infectious agents, studies targeting the precise oncogenic mechanisms of the viruses are the most abundant.

Human oncogenic viruses have been the in the centre of scientific attention for over 50 years. They represent a variety of viruses with a range in morphology, genetic material and, overall, viral life cycle and reproduction [4][10]. According to The World Health Organization, approximately 10% of infection-attributed cancers have viral aetiology [11]. The carcinogenic mechanisms of oncoviruses also vary widely [12] but they generally involve continued expression of specific viral oncogenes that regulate proliferative and antiapoptotic activities, dysregulation of cellular genomic instability through integration of the viral DNA into the host genome, viral promotion of DNA damage and immune evasion strategies [10][12]. However, it is significant to note that oncogenesis is an uncommon consequence of the viral infection, and it is developed mainly after a long-lasting chronic infection [10]. Moreover, the detection of a virus in a cancerous tissue does not necessarily establish causality [10].

2. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Merkel Cell Carcinoma

2.1. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus (MCPyV)

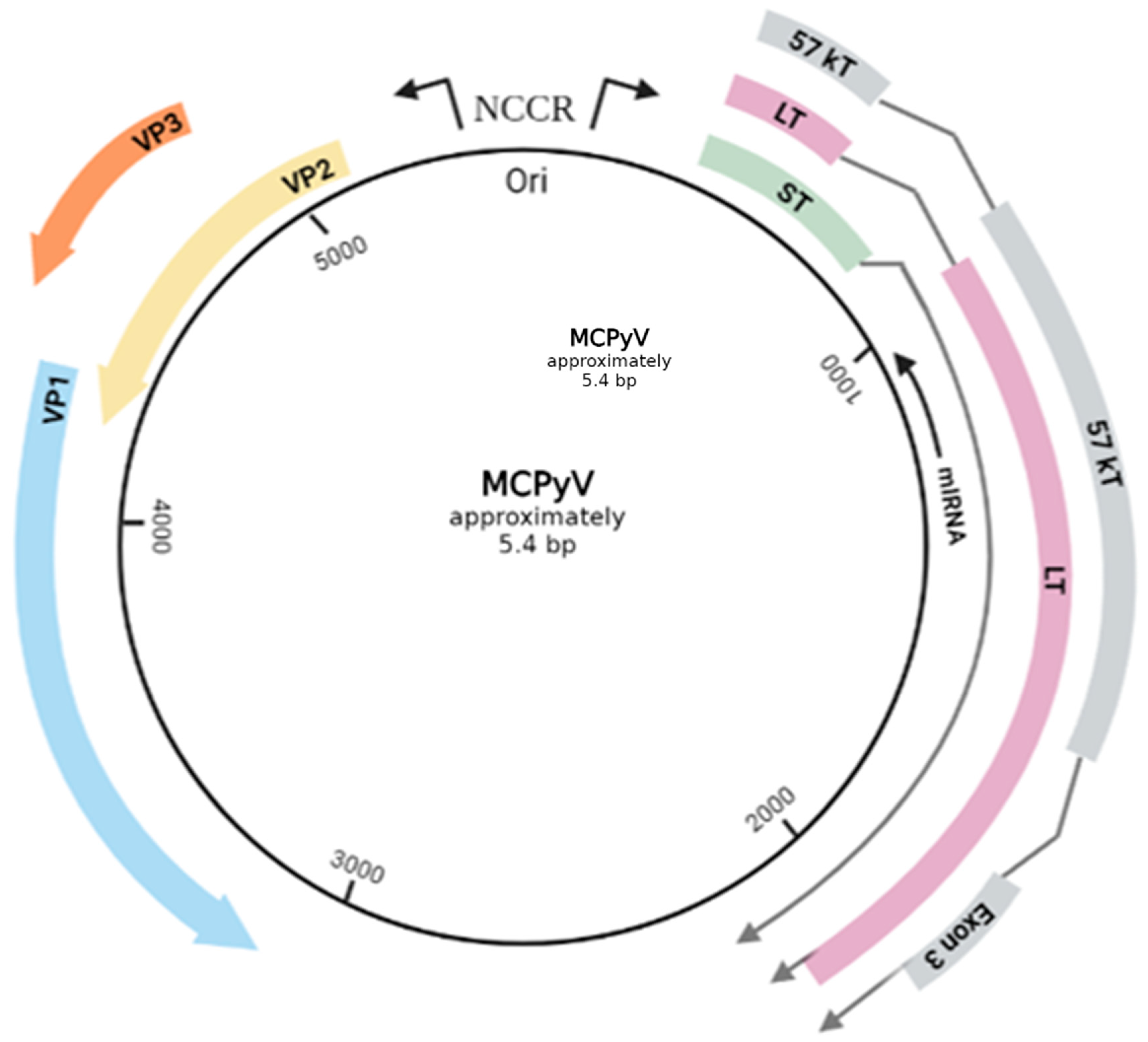

Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is the only member of the Polyomaviridae family with scientifically proven ability to cause oncogenesis in humans [13]. MCPyV exhibits the characteristic genomic and structural organization of the family (Figure 1). It is a small, non-enveloped virus, approximately 45 nm in diameter, with icosahedral capsids [14]. The genome is represented by a short (approximately 5.4 kb) double-stranded circular DNA [15], packed together with host-derived histones [16]. It is comprised of three main regions, classified based on the sequential priority in which they are expressed during infection: the early-coding region, the late-coding region, as well as a noncoding, regulatory region (NCRR) [17]. NCRR is located in-between the other two and does not encode any functional protein or RNA. It possesses an essential role in the viral life cycle regulation, since it contains both the viral origin of replication (Ori) and, also, various transcription promoters [18][19]. Immediately upon viral infection, the expression of the early region is initiated, encoding multiple, alternatively spliced RNA transcripts, leading to distinctive gene products that are generally involved in the replication of the viral genome [15]. Those are the large tumor antigen (LT), the small tumor antigen (sT), as well as a 57 kT antigens, along with the alternate LT ORF (ALTO) product [18][19]. The LT, sT and 57 kT antigens all share an identical sequence of 78 amino acids at their N-terminal [20]. Lastly, the viral genome also contains a gene, located on the late strand of the T antigen genes, with an opposite transcription orientation to the T antigens. The transcriptional product of this gene is a non-coding miRNA [18][19]. The most important viral antigens proven to play a vital part in the lytic infection are the MCPyV LT and sT antigens [21]. More specifically, the LT antigen is a multifunctional, pleiotropic protein of 700 amino acids that impacts several cellular proteins involved in both the host cell and the viral life cycles [16][20]. It is mainly nuclear located, though phosphorylation modifications may lead to different localization within the cell [16]. Structurally, it is composed of a highly conserved N-terminal region (CR1) and a C-terminal region with an origin-binding domain (OBD) and a helicase domain, both critical for viral DNA replication. In-between the two terminal regions there can be found sequences responsible for the protein–protein interactions of LT with host proteins that end up alternating the normal cell cycle (RB,p53) [20]. Regarding the sT protein, it shares the LT N-terminal region, but has a unique C-region made of a protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) binding site [20][22]. Following the expression of the early-coding locus and the replication of the viral DNA, the late region is transcriptionally activated to produce the structural components of the viral capsid, major capsid protein viral protein 1 (VP1) and the minor capsid protein 2 and 3 (VP2 and VP3) [18]. The presence of VP1 and VP2 is crucial for the viral entry into the cell, whereas VP3 cannot be detected in MCPyV-infected cells or in MCPyV virions, indicating a possible conditional expression pattern [16].

Figure 1. The genomic map of MCPyV circular, double stranded DNA. The early genes encode oncogenic proteins (LT, sT, 57 kT) and the late genes structural proteins (VP1. VP2, VP3). The NCCR (non-coding control region) includes Ori and regulates the viral gene expression. A gene, located on the late strand of the T antigen genes, with an opposite transcription orientation (reversed complementarity) to the T antigens produces a non-coding miRNA. The total length of the viral genome is approximately 5.4 bp. Created with BioRender.com (visited on 1 July 2022).

In general, MCPyV is a widespread and mostly asymptomatic resident of the skin in the human population [23][24][25]. Serological surveys for antibodies against viral antigens demonstrate that 20–40% of children 0–5 years old test positive [26], meaning that the first contact with this infectious agent occurs early in life [27], whereas positivity reaches 80% in individuals of age of 50 years and above [26][28][29]. Therefore, it is highly suggested that MCPyV is a member of the skin microbiome (virome) of the human body [30]. Moreover, the precise host cell tropism of MCPyV remains unclear. Interestingly, MCPyV seems to require both salicylic acid heparan sulphate upon its entrance [27][30][31], molecules ubiquitous in several cell types, though the replication of MCPyV has so far shown to be limited to keratinocytes [27] and fibroblasts from the dermis, and the lung [32]. Furthermore, among fibroblasts isolated from common model animals, only chimpanzee and human ones can support a vital level of MCPyV replication [33]. This lack of an eligible cell culture system for MCPyV infection [19], as well as the inability to establish an in vivo infection system [33], has limited the ability to understand the fundamentals of the viral behavior. Consequently, there is much to be elucidated with respect to MCPyV host potential reservoir cells and the complete MCPyV infectious cycle during infection. Despite the limitation regarding the target-cell preferences, MCPyV is not solely detectable within the skin, but also in respiratory samples, urine, and blood [18][34], as well as in samples extracted from numerous non-malignant tissues (e.g., spleen, bone marrow, stomach, heart), although with a comparatively low viral load [35]. Lastly, the route of MCPyV transmission has yet to be established, but suggested routes include primarily direct contact with the skin or saliva, and recently proposed ones, i.e., airborne and fecal–oral [16][27].

Nevertheless, MCPyV is not harmless in the minority of individuals and, on the contrary, it is considered the first, and, to date, the only polyomavirus directly implicated in the emergence of an aggressive, lethal human cancer, Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

2.2. Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC)

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, aggressive, neuroendocrine neoplasia of the human skin [36], originally described in 1972 by Cyril Taker [37]. With a nearly 50% mortality rate [38] and a high case-fatality [19], it is considered one of the most lethal skin malignancies, surpassing melanoma [39]. The low survival rates are a direct consequence of the rapid metastatic ability (distant, regional metastases or lymph node metastases) of MCC [27][38][40][41], combined with its intrinsic ability to resist immunological eradication [27][41], as well as a relatively poorly response to chemotherapeutic agents and constant recurrence [42][43][44]. Furthermore, MCC is characterized by several established risk factors, including advanced age (50 years and older), population features (fair skin), exposure to intense solar radiation (skin displayed mainly to UV rays) and immune deficiencies [40][41][45]. In the last few years, even though MCC is still considered uncommon, both the incidence as well as the mortality rate of MCC have sharply tripled [19] and are anticipated to rise further [46]. Once emerged, MCC appears as a fast growing red or purple nodule of trabecular, nodular, or diffuse shape [45]. Despite the given name, attributed to the phenotypical similarities of the tumour with the Merkel cells of the skin, the true cell origin of MCC is rigorously debated [41][47]. The initial favoured theory, that MCC arises from unrestrained growth of differentiated Merkel cells, is debated due to the post-mitotic nature of the Merkel cells, which makes them terminally differentiated, unable to undergo further cell division, and consequently, making their oncogenic potential limited [18][48]. In addition, Merkel cell have epidermal origin, in contrast to the dermis or subcutis layer origin of the MCCs [18]. Therefore, plenty of other suggestions have been made, such as that MCCs could potentially occur from Merkel cell precursor cells present at the hair follicles of the skin, or other epithelial, fibroblastic, or even B-cells, primarily in accordance with morphological similarities shared by MCC and these potential pedigrees [18][49][50].

The two major causative factors of MCC are Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) and ultraviolet radiation [39][51]. Hence, Merkel cell carcinomas can be subdivided into two major groups: the virus-associated MCCs (VP-MCCs) and the virus-negative MCCs (VN-MCCs or UV-MCCs). Despite evidently different aetiologies, both groups share mutations in vital cell-cycle related genes (meaning they regulate similar molecular paths in different means) [27][52][53][54], as well as similar disease phenotype [55] and same emergence location (on sun-exposed regions of the body, such as the head, neck, and limbs [56][57]). On the contrary, VP-MCCs seem to have an insignificant mutational burden and a lower number of somatic mutations compared to VN-MCCs [58][59][60][61]. Initially, the MCCs caused by UV-light overexposure have been attributed to approximately 20% of the total cases and are characterized by high accumulation of UV-derived DNA mutations, specifically on genes that encode tumour-specific UV-neoantigens, such as the retinoblastoma (pRb) pathway, RB1, TP53, and PIK3CA, along with mutations in host DDR and chromatin modulation pathways [41][51][58][59]. Such aberrations are crucial for MCC emergence, since the dysregulation results in both interruption of the cell cycle and induction of SOX2 expression, leading to neuroendocrine transformation [62]. MCPyV-negative MCCs also have increased levels of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) which could potentially enhance carcinogenesis [15].

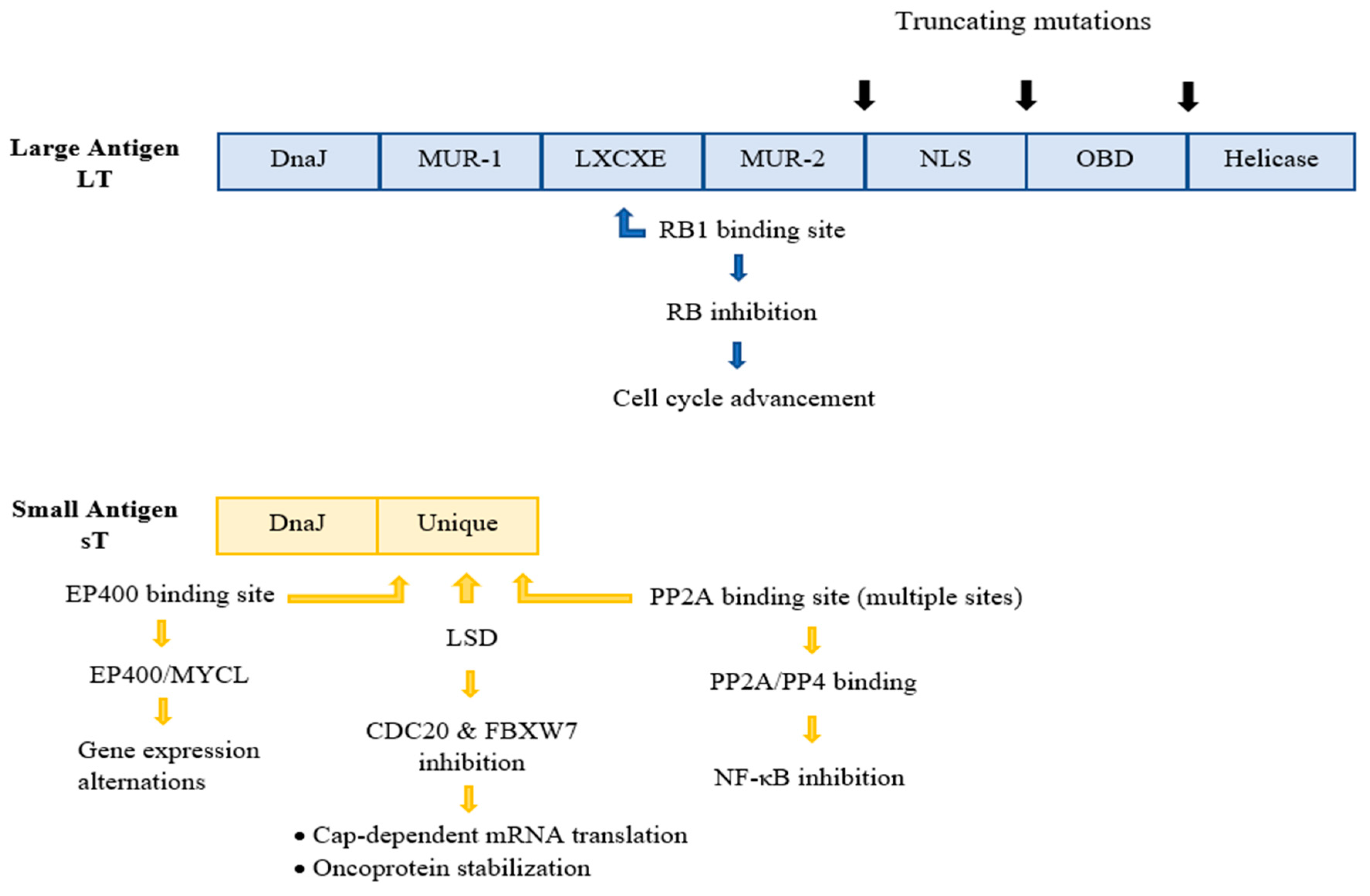

Whilst UV radiation is considered a strong risk factor and leads to MCC-related mutagenesis in VN tumours, the major causative factor of MCC is MCPyV, evident in the vast majority of MCC cases [38]. More specifically, MCPyV was first detected and isolated in 2008 by Feng and colleagues at the Pittsburgh Cancer Institute within the cells of the primary MCC tumour and a metastatic lymph node, using digital transcriptome subtraction assays. The viral genome, which was detected in 80% of the MCC samples, also exhibited a clonal integration pattern within several different chromosomal sites [13][27][38]. This identification of MCPyV was a significant leap in the comprehension of the pathogenesis of MCC in virus-associated MCC, but the exact role of MCPyV in MCC pathogenesis requires further investigation [19]. In the last few years, significant progress in decoding the mechanism of MCC-VP tumorigenesis has been observed. Thus, oncogenic transformation by MCPyV is hypothesized to be the outcome of two consecutive events [27]: (1) the incorporation of the viral DNA into the host genome, (2) the subsequent expression of the viral oncogenic proteins. Initially, the clonal incorporation of MCPyV DNA into the host genome transpires at generally random genomic sites, most commonly on chromosome 5. This event has been evident in up to 80% of all studied MCCs [63][64]. The integration takes place as either a single copy or as a concatemer of multiple copies, always in a manner that results in loss of replicative abilities of the virus before MCC development, but, simultaneously, in a way that preserves the expression of the so-called viral tumour (T) antigens [18][65]. The MCPyV-encoded antigens, sT and LT, are highly immunogenic and are required for the MCC development as well as the oncogenic phenotype maintenance [21][48]. They contribute to oncogenesis by targeting various host cell proteins involved in cell cycle control and proliferation [18]. The significance of the T antigens in MCC tumorigenesis is highlighted by the fact that their expression is required for optimal MCC cell growth and proliferation [9][66]. Depletion of these tumour antigens from VP-MCC cell lines, on the other hand, leads to cancer cell death [18]. Starting with the LT antigen, sequencing assays have indicated several truncating mutations within the C-terminus of LT, most probably caused by and during the viral genome integration process. These mutated LT antigens seem to lack the DNA binding domain–helicase activity, thus interrupting the viral DNA replication in MCC tumours [15]. However, the truncated LT proteins retain several other structural domains and motifs within the N-terminus region, resulting in interaction with the tumour-repressor retinoblastoma protein (pRb) [66], thus inactivating it and promoting cell cycle deregulation and cellular proliferation (Figure 2). MCPyV LT is also associated with Vam6/Vps39-like protein, which is potentially significant for the viral cell cycle [52]. The oncogenic significance of the LT antigen is further indicated by the observation that the silence of this antigen in VP-positive MCC-derived cells intervenes with the cell growth and promotes cell death [15][67]. All in all, the accumulation of mutations in the LT antigen plays a vital role in the carcinogenesis process, since these mutations not only downregulate the viral replication and viral load, promoting immune evasion, but also promote unrestrained cell proliferation. Regarding the sT antigen, it is more frequently detected in human MCC tumours than the LT antigen and is considered a more crucial ‘player’ for oncogenesis [16]. Experiments on transgenic mouse models have indicated a transformative ability of sTs in various organ systems, including in the epidermis [52]. Furthermore, the sT antigen is able to transform rat-1 fibroblasts in cell cultures [52]. ST has been found to interact with a variety of host cellular proteins and, therefore, exhibits a range of activities. Initially, sT’s PP2A region interacts and inhibits PP2A and PP4 phosphate complexes. This interaction promotes inhibition of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), as well as alternations in the cellular cytoskeleton, resulting in cell motility. Nevertheless, the PP2A binding domain is not considered crucial for carcinogenesis, since studies have shown that its presence is not required for cellular transformation by MCPyV ST31 [52]. An sT antigen region that is vital for the virus-induced oncogenesis is the LT-stabilizing domain (LSD), which has been suggested to interact with F-box/WD repeat-containing protein 7 (FBXW7) and cell division cycle protein 20 homologue (CDC20), resulting in inhibition of E3 ubiquitin ligases, and subsequent enhancement of the oncoprotein stability and cap-dependent mRNA translation, respectively. Additionally, research on sT has demonstrated its ability to promote changes in gene expression, by regulating both EP400 histone acetyltransferase and chromatin remodelling complex66 [52]. Lastly, studies suggest that sT might also interfere with the cell metabolism [52]. Therefore, sT antigen appears to possess a substantial role in MCPyV-related cancer emergence. Finally, immunocompromised patients display a higher (16-fold) relative risk for MCC development, opposed to the healthy population [16]. Therefore, immuno-suppression is classified as another crucial contributing factor in MCPyV-mediated carcinogenesis [41][68][69]. It is also imperative to mention that in MCPyV-positive MCCs, UV light may simply promote tumour growth through immunosuppressive effects on the tumour microenvironment [9].

Figure 2. The structural domains of the early gene region antigens, LT and sT. The LT and ST are products of alternative splicing of the region. In MCC, a truncated version of LT is expressed, characterized by mutations that eliminate domains of the C-terminus of LT, naming the nuclear localization signal (NLS), origin binding domain (OBD), and helicase domains. The crucial for the oncogenesis LXCXE RB-binding motif is preserved. ST contains several unique motifs with multiple sites that bind and interact with a variety of host cellular proteins. The DnaJ domains, conserved in both antigens, are related to viral replication. NLS, Nuclear localization signal; MUR, MCPyV unique region; OBD, Origin binding domain, PP2A protein phosphatase 2A; EP400, E1A-binding protein p400; MYCL, L-myc-1 proto-oncogene protein; LSD, NF-κΒ, Nuclear factor kappa B; LT-stabilizing domain; FBXW7m F-box/WD repeat-containing protein 7; CDC20, cell division cycle protein 20 homolog; PP4, Protein phosphatase 4.

According to molecular epidemiological studies, the prevalence of MCPyV in MCC varies widely depending on the region of interest [5][70], ranging between approximately 25% in Australia and 100% in a French study [70]. Subsequent studies demonstrated values of 76.0% in the United States population and 66.6% in Switzerland [5]. Furthermore, MCPyV DNA has been shown to be present in 55–79% of MCCs in Japanese patients [70]. The detection methods used for MCC diagnosis initiate with clinical examination and are followed by tissue biopsy through immunochemistry, a method that demonstrates characteristic histopathologic neuroendocrine features [41]. Immunohistochemistry aims to differentiate MCCs from other, morphologically similar, neuroendocrine tumours through characteristic staining of a variety of MCC epithelial and neuroendocrine markers, such as cytokeratin-20 (CK20), neurofilaments, CAM 5.2, TTF-1 and AE1/3 [71][72]. With the purpose of distinguishing the VP-MCCs from VN-MCCs, a series of identification techniques are performed, including serological anti-oncoprotein antibody detection and molecular techniques of viral DNA amplification and detection (PCR, qPCR) [73]. For the molecular assays, the most common primers used target the LT and sT gene and the VP1 and NCCR regions of the genome [73]. Lastly, for confirmation purposes, a combination of molecular and immunohistochemical analyses can be performed (since viral proteins can be detected in tumour tissues) [73]. On average, the viral genome copy number of MCPyV has been estimated to be 60 times lower in healthy tissues across the body compared to MCC samples [74]. The available treatment options for both UV- and virus-induced MCCs, are, so far, very limited. Surgical extraction followed by rounds of chemotherapy is the recommended route [41]. Due to the immunogenic properties of MCCs, a novel therapy based on immune checkpoint inhibitors has recently shown encouraging survival outcomes [60][75][76], though this approach is considered insufficient for the systemically immunosuppressed patients [77][78]. Lastly, therapeutic vaccines are currently being developed [9][79].

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Khan, N.; Afaq, F.; Mukhtar, H. Lifestyle as risk factor for cancer: Evidence from human studies. Cancer Lett. 2010, 293, 133–143.

- Hatta, M.N.A.; Mohamad Hanif, E.A.; Chin, S.F.; Neoh, H.M. Pathogens and Carcinogenesis: A Review. Biology 2021, 10, 533.

- de Martel, C.; Georges, D.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Clifford, G.M. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e180–e190.

- Chua, T.H.; Punjabi, L.S.; Khor, L.Y. Tissue Pathogens and Cancers: A Review of Commonly Seen Manifestations in Histo- and Cytopathology. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1410.

- De Flora, S.; La Maestra, S. Epidemiology of cancers of infectious origin and prevention strategies. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2015, 56, E15–E20.

- Masrour-Roudsari, J.; Ebrahimpour, S. Causal role of infectious agents in cancer: An overview. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 8, 153–158.

- Zella, D.; Gallo, R.C. Viruses and Bacteria Associated with Cancer: An Overview. Viruses 2021, 13, 1039.

- Cai, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Lan, K. (Eds.) Infectious agents associated cancers: Epidemiology and molecular biology. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 1018.

- Schiller, J.T.; Lowy, D.R. An Introduction to Virus Infections and Human Cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2021, 217, 1–11.

- Plummer, M.; de Martel, C.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Franceschi, S. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: A synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2016, 4, e609–e616.

- Schiller, J.T.; Lowy, D.R. Virus infection and human cancer: An overview. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2014, 193, 1–10.

- Feng, H.; Shuda, M.; Chang, Y.; Moore, P.S. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science 2008, 319, 1096–1100.

- Becker, M.; Dominguez, M.; Greune, L.; Soria-Martinez, L.; Pfleiderer, M.M.; Schowalter, R.; Buck, C.B.; Blaum, B.S.; Schmidt, M.A.; Schelhaas, M. Infectious Entry of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e02004-18.

- Krump, N.A.; You, J. From Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection to Merkel Cell Carcinoma Oncogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 739695.

- Prado, J.C.M.; Monezi, T.A.; Amorim, A.T.; Lino, V.; Paladino, A.; Boccardo, E. Human polyomaviruses and cancer: An overview. Clinics 2018, 73, e558s.

- Spurgeon, M.E.; Lambert, P.F. Merkel cell polyomavirus: A newly discovered human virus with oncogenic potential. Virology 2013, 435, 118–130.

- Yang, J.F.; You, J. Merkel cell polyomavirus and associated Merkel cell carcinoma. Tumour Virus Res. 2022, 13, 200232.

- Liu, W.; Krump, N.A.; Buck, C.B.; You, J. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection and Detection. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 144, e58950.

- Wendzicki, J.A.; Moore, P.S.; Chang, Y. Large T and small T antigens of Merkel cell polyomavirus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015, 11, 38–43.

- Baez, C.F.; Brandão Varella, R.; Villani, S.; Delbue, S. Human Polyomaviruses: The Battle of Large and Small Tumor Antigens. Virology 2017, 8, 1178122X17744785.

- Kwun, H.J.; Shuda, M.; Camacho, C.J.; Gamper, A.M.; Thant, M.; Chang, Y.; Moore, P.S. Restricted protein phosphatase 2A targeting by Merkel cell polyomavirus small T antigen. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 4191–4200.

- Kamminga, S.; van der Meijden, E.; Feltkamp, M.C.W.; Zaaijer, H.L. Seroprevalence of fourteen human polyomaviruses determined in blood donors. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206273.

- Pastrana, D.V.; Tolstov, Y.L.; Becker, J.C.; Moore, P.S.; Chang, Y.; Buck, C.B. Quantitation of human seroresponsiveness to Merkel cell polyomavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000578.

- Kean, J.M.; Rao, S.; Wang, M.; Garcea, R.L. Seroepidemiology of human polyomaviruses. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000363.

- Chen, T.; Hedman, L.; Mattila, P.S.; Jartti, T.; Ruuskanen, O.; Söderlund-Venermo, M.; Hedman, K. Serological evidence of Merkel cell polyomavirus primary infections in childhood. J. Clin. Virol. 2011, 50, 125–129.

- Stachyra, K.; Dudzisz-Śledź, M.; Bylina, E.; Szumera-Ciećkiewicz, A.; Spałek, M.J.; Bartnik, E.; Rutkowski, P.; Czarnecka, A.M. Merkel Cell Carcinoma from Molecular Pathology to Novel Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6305.

- Tolstov, Y.L.; Pastrana, D.V.; Feng, H.; Becker, J.C.; Jenkins, F.J.; Moschos, S.; Chang, Y.; Buck, C.B.; Moore, P.S. Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection II. MCV is a common human infection that can be detected by conformational capsid epitope immunoassays. Int. J. Cancer. 2009, 125, 1250–1256.

- Viscidi, R.P.; Rollison, D.E.; Sondak, V.K.; Silver, B.; Messina, J.L.; Giuliano, A.R.; Fulp, W.; Ajidahun, A.; Rivanera, D. Age-specific seroprevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus, BK virus, and JC virus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18, 1737–1743.

- Schowalter, R.M.; Pastrana, D.V.; Pumphrey, K.A.; Moyer, A.L.; Buck, C.B. Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2010, 7, 509–515.

- Schowalter, R.M.; Pastrana, D.V.; Buck, C.B. Glycosaminoglycans and sialylated glycans sequentially facilitate Merkel cell polyomavirus infectious entry. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002161.

- Liu, W.; Yang, R.; Payne, A.S.; Schowalter, R.M.; Spurgeon, M.E.; Lambert, P.F.; Xu, X.; Buck, C.B.; You, J. Identifying the Target Cells and Mechanisms of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016, 19, 775–787.

- Liu, W.; Krump, N.A.; MacDonald, M.; You, J. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection of Animal Dermal Fibroblasts. J Virol. 2018, 92, e01610-17.

- Mertz, K.D.; Junt, T.; Schmid, M.; Pfaltz, M.; Kempf, W. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 1146–1151.

- Matsushita, M.; Kuwamoto, S.; Iwasaki, T.; Higaki-Mori, H.; Yashima, S.; Kato, M.; Murakami, I.; Horie, Y.; Kitamura, Y.; Hayashi, K. Detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in the human tissues from 41 Japanese autopsy cases using polymerase chain reaction. Intervirology 2013, 56, 1–5.

- Elder, D.E.; Bastian, B.C.; Cree, I.A.; Massi, D.; Scolyer, R.A. The 2018 World Health Organization Classification of Cutaneous, Mucosal, and Uveal Melanoma: Detailed Analysis of 9 Distinct Subtypes Defined by Their Evolutionary Pathway. Arch. Pathol. Lab Med. 2020, 144, 500–522.

- Toker, C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch. Dermatol. 1972, 105, 107–110.

- Becker, J.C.; Stang, A.; DeCaprio, J.A.; Cerroni, L.; Lebbé, C.; Veness, M.; Nghiem, P. Merkel cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 26, 17077.

- Pietropaolo, V.; Prezioso, C.; Moens, U. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 1774.

- Walsh, N.M.; Cerroni, L. Merkel cell carcinoma: A review. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2021, 48, 411–421.

- Dellambra, E.; Carbone, M.L.; Ricci, F.; Ricci, F.; Di Pietro, F.R.; Moretta, G.; Verkoskaia, S.; Feudi, E.; Failla, C.M.; Abeni, D.; et al. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 718.

- Allen, P.J.; Bowne, W.B.; Jaques, D.P.; Brennan, M.F.; Busam, K.; Coit, D.G. Merkel cell carcinoma: Prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 2300–2309.

- Nghiem, P.; Kaufman, H.L.; Bharmal, M.; Mahnke, L.; Phatak, H.; Becker, J.C. Systematic literature review of efficacy, safety and tolerability outcomes of chemotherapy regimens in patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2017, 13, 1263–1279.

- Iyer, J.G.; Blom, A.; Doumani, R.; Lewis, C.; Tarabadkar, E.S.; Anderson, A.; Ma, C.; Bestick, A.; Parvathaneni, U.; Bhatia, S.; et al. Response rates and durability of chemotherapy among 62 patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 2294–2301.

- Patel, P.; Hussain, K. Merkel cell carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 814–819.

- Paulson, K.G.; Park, S.Y.; Vandeven, N.A.; Lachance, K.; Thomas, H.; Chapuis, A.G.; Harms, K.L.; Thompson, J.A.; Bhatia, S.; Stang, A.; et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 457–463.

- Liu, W.; MacDonald, M.; You, J. Merkel cell polyomavirus infection and Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 20, 20–27.

- Becker, J.C.; Stang, A.; Hausen, A.Z.; Fischer, N.; DeCaprio, J.A.; Tothill, R.W.; Lyngaa, R.; Hansen, U.K.; Ritter, C.; Nghiem, P.; et al. Epidemiology, biology and therapy of Merkel cell carcinoma: Conclusions from the EU project IMMOMEC. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 341–351.

- Akaike, T.; Nghiem, P. Scientific and clinical developments in Merkel cell carcinoma: A polyomavirus-driven, often-lethal skin cancer. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2022, 105, 2–10.

- Sauer, C.M.; Haugg, A.M.; Chteinberg, E.; Rennspiess, D.; Winnepenninckx, V.; Speel, E.J.; Becker, J.C.; Kurz, A.K.; Zur Hausen, A. Reviewing the current evidence supporting early B-cells as the cellular origin of Merkel cell carcinoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 116, 99–105.

- Wong, S.Q.; Waldeck, K.; Vergara, I.A.; Schröder, J.; Madore, J.; Wilmott, J.S.; Colebatch, A.J.; De Paoli-Iseppi, R.; Li, J.; Lupat, R.; et al. UV-Associated Mutations Underlie the Etiology of MCV-Negative Merkel Cell Carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 5228–5234.

- Harms, P.W.; Harms, K.L.; Moore, P.S.; DeCaprio, J.A.; Nghiem, P.; Wong, M.K.K.; Brownell, I. International Workshop on Merkel Cell Carcinoma Research (IWMCC) Working Group. The biology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: Current understanding and research priorities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 763–776.

- DeCaprio, J.A. Merkel cell polyomavirus and Merkel cell carcinoma. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 2017, 372, 20160276.

- Gravemeyer, J.; Spassova, I.; Verhaegen, M.E.; Dlugosz, A.A.; Hoffmann, D.; Lange, A.; Becker, J.C. DNA-methylation patterns imply a common cellular origin of virus- and UV-associated Merkel cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2022, 41, 37–45.

- Ahmed, M.M.; Cushman, C.H.; DeCaprio, J.A. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus: Oncogenesis in a Stable Genome. Viruses 2022, 14, 58.

- Schadendorf, D.; Lebbé, C.; Zur Hausen, A.; Avril, M.F.; Hariharan, S.; Bharmal, M.; Becker, J.C. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, prognosis, therapy and unmet medical needs. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 71, 53–69.

- Becker, J.C.; Kauczok, C.S.; Ugurel, S.; Eib, S.; Bröcker, E.B.; Houben, R. Merkel cell carcinoma: Molecular pathogenesis, clinical features and therapy. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2008, 6, 709–719.

- Horny, K.; Gerhardt, P.; Hebel-Cherouny, A.; Wülbeck, C.; Utikal, J.; Becker, J.C. Mutational Landscape of Virus- and UV-Associated Merkel Cell Carcinoma Cell Lines Is Comparable to Tumor Tissue. Cancers 2021, 13, 649.

- DeCaprio, J.A. Molecular Pathogenesis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2021, 16, 69–91.

- Knepper, T.C.; Montesion, M.; Russell, J.S.; Sokol, E.S.; Frampton, G.M.; Miller, V.A.; Albacker, L.A.; McLeod, H.L.; Eroglu, Z.; Khushalani, N.I.; et al. The Genomic Landscape of Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Clinicogenomic Biomarkers of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5961–5971.

- Goh, G.; Walradt, T.; Markarov, V.; Blom, A.; Riaz, N.; Doumani, R.; Stafstrom, K.; Moshiri, A.; Yelistratova, L.; Levinsohn, J.; et al. Mutational landscape of MCPyV-positive and MCPyV-negative Merkel cell carcinomas with implications for immunotherapy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 3403–3415.

- Harold, A.; Amako, Y.; Hachisuka, J.; Bai, Y.; Li, M.Y.; Kubat, L.; Gravemeyer, J.; Franks, J.; Gibbs, J.R.; Park, H.J. Conversion of Sox2-dependent Merkel cell carcinoma to a differentiated neuron-like phenotype by T antigen inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 20104–20114.

- Martel-Jantin, C.; Filippone, C.; Cassar, O.; Peter, M.; Tomasic, G.; Vielh, P.; Brière, J.; Petrella, T.; Aubriot-Lorton, M.H.; Mortier, L.; et al. Genetic variability and integration of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Virology 2012, 426, 134–142.

- Starrett, G.J.; Thakuria, M.; Chen, T.; Marcelus, C.; Cheng, J.; Nomburg, J.; Thorner, A.R.; Slevin, M.K.; Powers, W.; Burns, R.T.; et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of virus-positive and virus-negative Merkel cell carcinoma. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 30.

- Czech-Sioli, M.; Günther, T.; Therre, M.; Spohn, M.; Indenbirken, D.; Theiss, J.; Riethdorf, S.; Qi, M.; Alawi, M.; Wülbeck, C.; et al. High-resolution analysis of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus in Merkel Cell Carcinoma reveals distinct integration patterns and suggests NHEJ and MMBIR as underlying mechanisms. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008562.

- Spurgeon, M.E.; Cheng, J.; Ward-Shaw, E.; Dick, F.A.; DeCaprio, J.A.; Lambert, P.F. Merkel cell polyomavirus large T antigen binding to pRb promotes skin hyperplasia and tumor development. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010551.

- Houben, R.; Shuda, M.; Weinkam, R.; Schrama, D.; Feng, H.; Chang, Y.; Moore, P.S.; Becker, J.C. Merkel cell polyomavirus-infected Merkel cell carcinoma cells require expression of viral T antigens. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 7064–7072.

- Ma, J.E.; Brewer, J.D. Merkel cell carcinoma in immunosuppressed patients. Cancers 2014, 6, 1328–1350.

- Koljonen, V.; Kukko, H.; Pukkala, E.; Sankila, R.; Böhling, T.; Tukiainen, E.; Sihto, H.; Joensuu, H. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients have a high risk of Merkel-cell polyomavirus DNA-positive Merkel-cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 101, 1444–1447.

- Wijaya, W.A.; Liu, Y.; Qing, Y.; Li, Z. Prevalence of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus in Normal and Lesional Skin: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 868781.

- Pasternak, S.; Carter, M.D.; Ly, T.Y.; Doucette, S.; Walsh, N.M. Immunohistochemical profiles of different subsets of Merkel cell carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2018, 82, 232–238.

- Jaeger, T.; Ring, J.; Andres, C. Histological, immunohistological, and clinical features of merkel cell carcinoma in correlation to merkel cell polyomavirus status. J. Skin Cancer 2012, 2012, 983421.

- Ursu, R.G.; Damian, C.; Porumb-Andrese, E.; Ghetu, N.; Cobzaru, R.G.; Lunca, C.; Ripa, C.; Costin, D.; Jelihovschi, I.; Petrariu, F.D.; et al. Merkel Cell Polyoma Virus and Cutaneous Human Papillomavirus Types in Skin Cancers: Optimal Detection Assays, Pathogenic Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Vaccination. Pathogens 2022, 11, 479.

- Loyo, M.; Guerrero-Preston, R.; Brait, M.; Hoque, M.O.; Chuang, A.; Kim, M.S.; Sharma, R.; Liégeois, N.J.; Koch, W.M.; Califano, J.A. Quantitative detection of Merkel cell virus in human tissues and possible mode of transmission. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 2991–2996.

- Nghiem, P.; Bhatia, S.; Lipson, E.J.; Sharfman, W.H.; Kudchadkar, R.R.; Brohl, A.S.; Friedlander, P.A.; Daud, A.; Kluger, H.M.; Reddy, S.A.; et al. Three-year survival, correlates and salvage therapies in patients receiving first-line pembrolizumab for advanced Merkel cell carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002478.

- Rabinowits, G.; Lezcano, C.; Catalano, P.J.; McHugh, P.; Becker, H.; Reilly, M.M.; Huang, J.; Tyagi, A.; Thakuria, M.; Bresler, S.C.; et al. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Oncologist 2018, 23, 814–821.

- Leroy, V.; Gerard, E.; Dutriaux, C.; Prey, S.; Gey, A.; Mertens, C.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Pham-Ledard, A. Adverse events need for hospitalization and systemic immunosuppression in very elderly patients (over 80 years) treated with ipilimumab for metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2019, 68, 545–551.

- Johnson, D.B.; Sullivan, R.J.; Menzies, A.M. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in challenging populations. Cancer 2017, 123, 1904–1911.

- Tabachnick-Cherny, S.; Pulliam, T.; Church, C.; Koelle, D.M.; Nghiem, P. Polyomavirus-driven Merkel cell carcinoma: Prospects for therapeutic vaccine development. Mol. Carcinog. 2020, 59, 807–821.

More

Information

Subjects:

Virology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

664

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

16 Jan 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No