Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yuxing Bai | -- | 2303 | 2023-01-13 10:53:23 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 2303 | 2023-01-16 01:56:04 | | | | |

| 3 | Dean Liu | -5 word(s) | 2298 | 2023-01-16 08:48:25 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Zhu, M.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, H.H.K.; Dai, Z.; Yu, K.; Xiao, L.; Schneider, A.; Weir, M.D.; Oates, T.W.; Bai, Y.; et al. Effects of Metformin Delivery. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40155 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Zhu M, Zhao Z, Xu HHK, Dai Z, Yu K, Xiao L, et al. Effects of Metformin Delivery. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40155. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Zhu, Minjia, Zeqing Zhao, Hockin H. K. Xu, Zixiang Dai, Kan Yu, Le Xiao, Abraham Schneider, Michael D. Weir, Thomas W. Oates, Yuxing Bai, et al. "Effects of Metformin Delivery" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40155 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Zhu, M., Zhao, Z., Xu, H.H.K., Dai, Z., Yu, K., Xiao, L., Schneider, A., Weir, M.D., Oates, T.W., Bai, Y., & Zhang, K. (2023, January 13). Effects of Metformin Delivery. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/40155

Zhu, Minjia, et al. "Effects of Metformin Delivery." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 January, 2023.

Copy Citation

Bone tissue engineering is a promising approach that uses seed-cell-scaffold drug delivery systems to reconstruct bone defects caused by trauma, tumors, or other diseases (e.g., periodontitis). Metformin, a widely used medication for type II diabetes, has the ability to enhance osteogenesis and angiogenesis by promoting cell migration and differentiation. Metformin promotes osteogenic differentiation, mineralization, and bone defect regeneration via activation of the AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway. Bone tissue engineering depends highly on vascular networks for adequate oxygen and nutrition supply.

metformin

bone tissue engineering

osteogenesis

angiogenesis

1. Introduction

Metformin is an antidiabetic agent used as a first-choice medication for type II diabetes mellitus. With the chemical formula C4H11N5 (N,N-dimethyl biguanide), metformin is a small-molecule compound that has no known metabolites [1]. The effects and mechanisms of metformin have been extensively studied and reviewed; however, new insights and therapeutic uses of metformin are still being discovered. In vitro and in vivo studies have suggested that metformin also has the potential to protect the cardiovascular system, alleviate the effects of aging, ameliorate excess blood lipids, and promote osteogenesis and hard tissue regeneration [2]. A deeper understanding of the mechanism of the signaling pathways and the target tissues of metformin provided compelling evidence that metformin can be applied to treat various diseases, including coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [3]. Importantly, metformin has demonstrated a significant contribution to repairing bone defects and promoting angiogenesis [4][5][6][7][8].

Bone tissue engineering is a promising method that uses seed-cell-scaffold drug delivery systems to reconstruct bone defects caused by trauma and tumors, as well as other applications, such as dental hard tissue regeneration and periodontal regeneration [9]. The effects of metformin in bone tissue engineering and its promising clinical applications could contribute to diagnosis and treatment of bone defects (Figure 1). Metformin can be delivered locally via scaffolds to enhance osteogenesis and angiogenesis, and the underlying mechanism of its effects is believed to involve the activation of AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) or non-AMPK-specific pathways. Osteogenesis and adipogenesis are competing and reciprocal pathways; therefore, hyperglycemic conditions are more likely to promote the adipogenic differentiation of the target tissue [10]. Metformin has the ability to enhance osteogenesis by ameliorating hyperglycemic conditions, regulating sugar metabolism, and promoting cell migration [11]. In addition, metformin promotes bone mineralization and bone defect regeneration through different target tissues, including stem cells and non-stem cells. Emerging evidence shows that several types of stem cells could be driven toward the osteogenic lineage in the presence of metformin [12][13]. Previous studies also reported that metformin could facilitate the proliferation and osteogenesis of periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) and dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) [9][14].

Figure 1. The roles of metformin in bone tissue engineering. The effects of metformin in bone tissue engineering. The promising clinical application metformin could contribute to diagnosis and treatment of bone defects. (a–e) Schematic illustrating metformin delivery via biomaterials, mainly via scaffolds, and its effects on bone and dental tissue engineering. Note that metformin exerts its effects by: (a) enhancing osteogenesis; (b) enhancing angiogenesis; (c) affecting the AMPK pathway; and (d) acting in a concentration-dependent manner. (e) The clinical applications of metformin. The underlying mechanism of metformin (through the AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway) is discussed in detail in the text.

The key to effective bone and dental hard tissue regeneration is the proper coupling of osteogenesis and angiogenesis [15][16]. Large bone defects do not self-heal when left untreated [17]. Self-healing osteogenesis alone cannot repair large bone defects, and external interventions and regenerative techniques are required to solve this major challenge in bone tissue engineering. Promoting angiogenesis and vascular capillaries is a promising strategy for therapeutic bone regeneration [18]. In recent years, research has focused on the contradictory effects of metformin, and the mechanisms of the anti-angiogenesis and angiogenesis of metformin are under investigation [12][19][20].

Metformin also has the ability to inhibit chronic inflammation to promote osteogenesis indirectly. The anti-inflammatory effects of metformin were achieved not only by altering body metabolic parameters, such as hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, but also by activating anti-inflammatory pathways or the immune system. Metformin was reported to have a direct anti-inflammatory action by inhibition of nuclear factor κB via adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK) dependent and independent pathways [21][22]. AMPK is involved in various upstream and downstream pathways such as the AMPK/mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR) pathway in mammals, extracellular regulated kinase (ERK)/AMPK with carbon dots, and the liver kinase B1 (LKB1)/AMPK pathway [23]. In addition, metformin has a dose-dependent effect.

2. Metformin Promotes Bone Repair and Regeneration

Bone defects are often caused by trauma, tumors, and other chronic diseases, such as periodontitis. Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease caused by plaque [24]. Traditional periodontal treatments have the ability to alleviate inflammation and suppress the progression of the inflammatory process to a certain extent [25]. However, when bone loss caused by periodontitis reaches a critical size, large bone defects cannot be repaired if treated only by the traditional treatments mentioned above. It remains an unsolved problem in restoring the structure and function of periodontitis bone loss.

Researchers developed drug delivery bone tissue engineering systems for regeneration applications. Among them, a calcium phosphate cement (CPCs)/alginate-hydrogel-microfiber (MF) scaffold system was developed to protect seed cells and transfer drugs to their target tissues. When seeded in this scaffold system, cells have relatively good biocompatibility and viability (Figure 2A–I) [9]. Moreover, this scaffold system also has an ideal mechanical strength and porous structure and could degrade within 3 to 4 days, releasing the encapsulated cells and drugs. CPCs have similar flexural strength, sheer strength, and other mechanical properties to alveolar bone. They also have a certain effect on osteo-induction [26]. MF could provide a porous structure for cells to seed, proliferate, and differentiate. When MF degrades, a microvascular-like structure could replace it, which has positive effects on angiogenesis [9]. Studies have shown that the incorporation of metformin into the CPC-MF scaffold system had no negative effect on cell viability compared with the scaffold system without metformin (Figure 2J–K) [9][27]. Moreover, the CPC-MF scaffold system is injectable and can form different shapes before its coagulation, which could better adapt to irregular bone defect sites, such as narrow, deep, and complex periodontal pockets.

Figure 2. Methods of seed-cell drug delivery via a calcium phosphate cement (CPCs)/alginate-hydrogel-microfiber (MF) scaffold system. Live/dead staining images of cells seeding on the CPC-MF scaffold system at days 1, 7, and 14 (A–I); live cell density and percentages of live cells encapsulated in CPC-MF scaffold system (J,K); synthesis of bone minerals by the encapsulated stem cells, which was enhanced by the encapsulated metformin. Alizarin red (ARS) staining and cell-synthesized mineral quantification of human periodontal ligament cells (hPDLSCs) on CPC-MF scaffold system with or without metformin (L,M) Values with dissimilar letters (a,b,c) are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05). (Adapted from reference [9], with permission).

Zhao et al. [9] showed that when seeded into the CPC-MF scaffold, hPDLSCs proliferated, osteo-differentiated, and angio-differentiated well. Seed cells exhibited high expression levels of osteogenic genes, ALP (encoding alkaline phosphatase, RUNX2 (encoding RUNX family transcription factor 2), OCN (encoding osteocalcin), and OSX (encoding osterix) at day 14. The peak osteogenic gene expression levels of the ‘metformin + osteogenic’ group were significantly higher than those of osteogenesis only group (without adding metformin) at days 7 and 14. The gene expression values of groups with metformin were about three- to four-fold higher than those of the groups without metformin. In addition, the ALP activity of the groups with metformin were three-fold higher than that of the groups without metformin at day 14. Thus, metformin could enhance the ALP activity of hPDLSCs on the CPC-MF scaffold system. Cell-synthesized bone mineralization, stained with alizarin red (ARS), was deeper and denser with increasing culture time, indicating excellent bone regeneration capability and applicability in clinical practice. Groups with metformin showed darker ARS staining than all the groups without metformin. Quantitative analysis of bone matrix mineral synthesis by hPDLSCs on the CPC-MF scaffold system showed that the groups with metformin synthesized two- to three-fold more bone mineral than that of the groups without metformin at days 7 and day 14, respectively (Figure 2L–M).

The optimal concentration of metformin in bone repair and regeneration remains unknown. There are distinctive differences regarding its dosage either for different target tissues or different administration methods. Notably, an oral dose of 500–1500 mg metformin is widely used in clinical practice [28]. The following section reviewed both in vitro doses for local administration and in vivo doses of metformin.

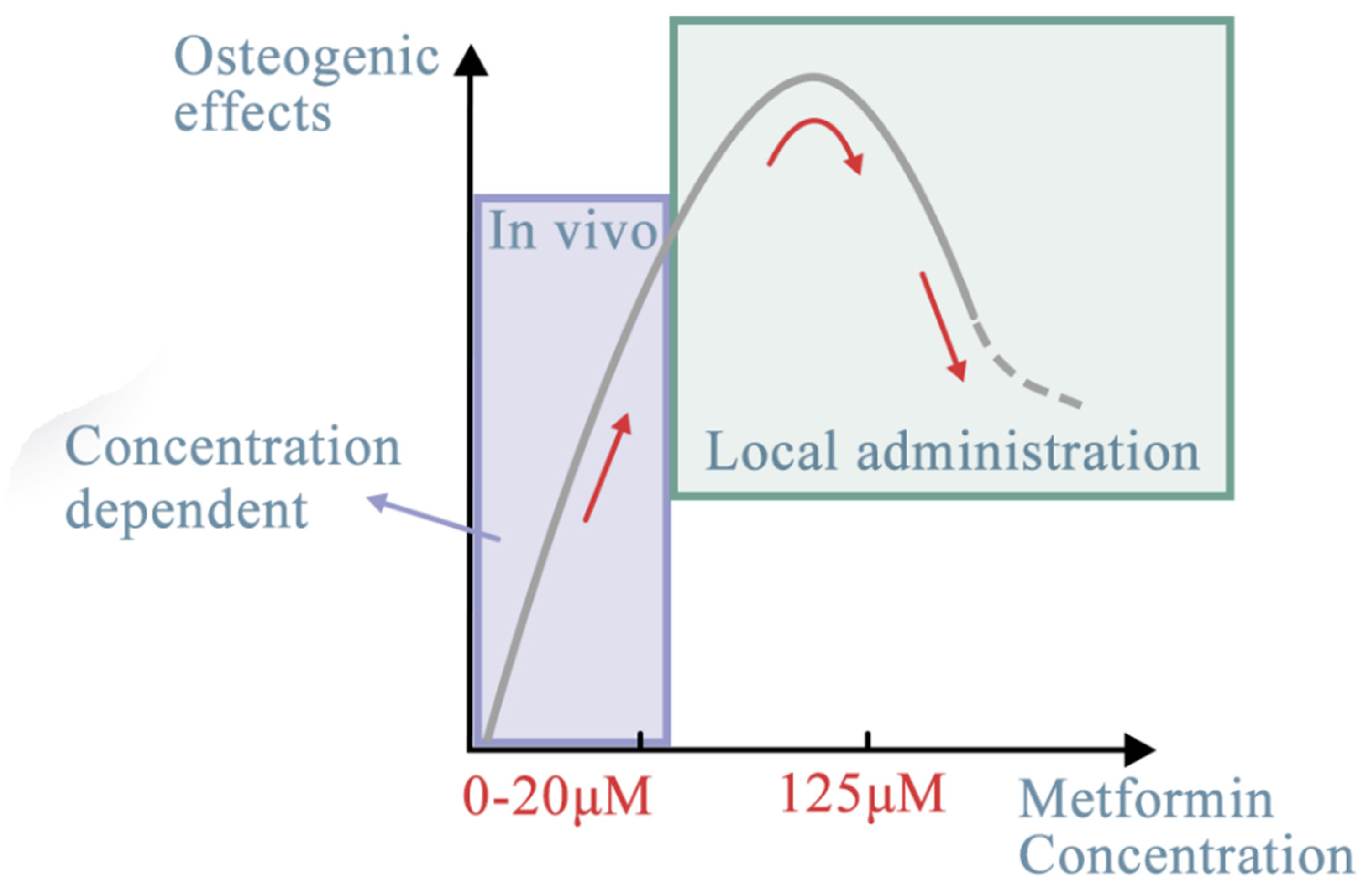

Clinically relevant doses of metformin were demonstrated to be associated with the osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of iPSC-MSCs [29]. Notably, there are large differences in the optimal concentration of metformin for different cell types, suggesting that it is important to explore the most suitable concentration of metformin for its application in tissue engineering [29]. It was reported that metformin promotes osteoblastic differentiation through AMPK signaling at doses ranging from 0.5 to 500 μM [30]. This was specifically demonstrated via a dose-dependent effect on cell proliferation as well as an increase in extracellular mineral nodule formation and the most recognized osteogenic markers. The previous study found that after treating MSCs cells with increasing doses of metformin (0–20 μM), metformin increased cell viability in a dose-dependent manner [30]. These findings underscore the importance of using therapeutically relevant doses when attempting to extrapolate in vitro results to the human clinical setting. Pharmacokinetic studies verified that within 2–4 h after an oral dose of 500–1500 mg, plasma concentrations of metformin in patients ranged from 2.7 to 20 μM [31].

Furthermore, sustained cell growth was observed under different treatment conditions. Sun et al. [7] reported that 125 μM was the optimal concentration of metformin for osteogenic differentiation and could promote implant osseointegration in rats. At concentrations over 200 µM, metformin inhibited the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs [7]. The pro-osteogenic function of metformin during in vitro and in vivo osteogenesis of adipose-derived stromal cells was assessed [32]. The in vitro experiments showed that metformin added into the culture medium at a concentration of 500 µM promoted the differentiation of adipose-derived stromal cells into bone-forming cells and increased the formation of mineralized extracellular matrix. The in vivo models revealed that metformin at a dose of 250 mg/kg/day accelerated bone healing and facilitated new bone callus formation at fracture sites in a rat cranial defect model [30]. It was also reported that 100 µM metformin had a prominent positive effect on the osteogenic differentiation and a negative effect on the adipogenic differentiation of PDLSCs, which has important implications for the application of metformin in PDLSC-based osteogenesis and bone regeneration [33] (Table 1, Figure 3).

Table 1. Effects of metformin concentration on different target stem cells.

| Target Stem Cells | Metformin Concentration | In Vivo/In Vitro (Local Administration) | The Effects of Metformin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC-MSCs | 0.5-500 μM | In vivo | Promoted osteoblastic differentiation through AMPK signaling | [29] |

| 0–20 μM | In vivo | Increased cell viability in a dose-dependent manner | [30] | |

| BMSCs | 125 μM | In vivo | The optimal concentration | [7] |

| over 200 µM | In vivo | Inhibited the osteogenic differentiation | ||

| Adipose-derived stromal cells | 500 µM | In vitro | Increased the formation of mineralized extracellular matrix | [32] |

| 250 mg/kg/day | In vivo | Accelerated bone healing and facilitated new bone callus formation | ||

| hPDLSCs | 100 µM | In vivo | Positive effect on the osteogenic differentiation Negative effect on the adipogenic differentiation |

[33] |

| Human endometrial stem cells | 10 wt% | In vivo | Improve osteogenic capability GBR application |

[13] |

| In vitro | ||||

| 10 to 15 wt% | In vivo | Decreased the viability of cell cultured on the surface | ||

| In vitro | ||||

| DPSCs | 20 wt% | In vitro | Restored the tooth cavity, provided protection for dental pulp, | [34] |

| BMSCs | 0, 10, 50, 100, and 200 μM | In vivo | Increase mechanical strength and new bone volume | [35] |

| In vitro |

Effects of metformin concentration on different target stem cells. The optimal concentration of metformin, ranging from 0.5 to 500 μM, could have better osteogenic effects through the AMPK signaling pathway.

Figure 3. Effects of metformin concentration on different target stem cells. The optimal concentration of metformin, ranging from 0.5 to 500 μM, could have better osteogenic effects through the AMPK signaling pathway. With different target stem cells, in vivo or in vitro (local administration), the dose-dependent effect may be different (red line). The effects of metformin, despite regulating more or less the same signaling pathways, differ depending on the target tissues [36], whether they are stem cells or non-cell materials. For seed cells, it mostly depends on their cellular origin and osteogenic lineage. Researchers discuss the potential targeted seed cells from within or outside of the oral cavity. The oral cavity is a special environment for targeted stem cells. Its complexity derives from its composition [37]. For example, the periodontal complex consists of hard tissues (alveolar bones, cementum), soft tissues (periodontal ligament fibers, gingival tissues), blood vessels, and nerves [38]. Other than non-cell materials, stem cells are categorized into six sources: MSCs, dental-derived cells, BMSCs, hi-PSCs, cancer cells, and immune cells. In the following section, each of these sources is reviewed.

Local administration of metformin has also been studied. A novel guided bone regeneration (GBR) membrane containing polycaprolactone (PCL) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) with different concentrations of metformin was developed to improve osteogenic capability [13]. The results of that study confirmed the high potential of co-cultured stem cells with 10 wt% metformin PCL/PVA membranes for GBR applications [13]. Another model system containing 20 wt% metformin incorporated into resin was established for localized delivery of drugs into bone defect sites. The metformin-loaded resin could help restore the tooth cavity, provide protection for dental pulp, and prevent microleakage during restoration [34]. The effects of topical application of metformin on promoting new bone formation and remodeling were also evaluated [35]. Tendon–bone interface healing involves fine osteogenesis at the repair site. In vitro experiments used BMSCs with different concentrations of metformin (0, 10, 50, 100, and 200 μM) cultured together. The results showed that the mechanical strength and new bone volume of the metformin-applied group were significantly higher than those of the control group. However, the exact concentration and the pharmacokinetic curve of metformin should be defined in specific clinical applications. Further studies on the effect of metformin concentration are still needed.

A previous study showed that metformin could activate the AMPK pathways to induce the differentiation of MSCs into osteoblasts, promote their osteogenic differentiation, promote mineralization, and thus regenerate bone defects [38].

References

- Triggle, C.R.; Mohammed, I.; Bshesh, K.; Marei, I.; Ye, K.; Ding, H.; MacDonald, R.; Hollenberg, M.D.; Hill, M.A. Metformin: Is it a drug for all reasons and diseases? Metabolism 2022, 133, 155223.

- Kawakita, E.; Yang, F.; Kumagai, A.; Takagaki, Y.; Kitada, M.; Yoshitomi, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Ishigaki, Y.; Kanasaki, K.; et al. Metformin Mitigates DPP-4 Inhibitor-Induced Breast Cancer Metastasis via Suppression of mTOR Signaling. Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 61–73.

- Al-Salameh, A.; Wiernsperger, N.; Cariou, B.; Lalau, J.-D. A comment on metformin and COVID-19 with regard to “Metformin use is associated with a decrease in the risk of hospitalization and mortality in COVID-19 patients with diabetes: A population-based study in Lombardy”. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24, 1888.

- Sun, C.-K.; Weng, P.-W.; Chang, J.Z.-C.; Lin, Y.-W.; Tsuang, F.-Y.; Lin, F.-H.; Tsai, T.-H.; Sun, J.-S. Metformin-Incorporated Gelatin/Hydroxyapatite Nanofiber Scaffold for Bone Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part A 2022, 28, 1–12.

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Yu, J.; Ding, R.; Pei, D.; Zhang, Y.; He, G.; Cheng, Y.; Li, A. Injectable hydrogels with high drug loading through B-N coordination and ROS-triggered drug release for efficient treatment of chronic periodontitis in diabetic rats. Biomaterials 2022, 282, 121387.

- Shen, M.; Yu, H.; Jin, Y.; Mo, J.; Sui, J.; Qian, X.; Chen, T. Metformin Facilitates Osteoblastic Differentiation and M2 Macrophage Polarization by PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway in Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2022, 2022, 9498876.

- Sun, R.; Liang, C.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Y.; Geng, W.; Li, J. Effects of metformin on the osteogenesis of alveolar BMSCs from diabetic patients and implant osseointegration in rats. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 1170–1180.

- Leng, T.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Wang, W.; Qu, X.; Lei, B. Bioactive anti-inflammatory antibacterial metformin-contained hydrogel dressing accelerating wound healing. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 135, 212737.

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Schneider, A.; Gao, X.; Ren, K.; Weir, M.D.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, L.; Bai, Y.; et al. Human periodontal ligament stem cell seeding on calcium phosphate cement scaffold delivering metformin for bone tissue engineering. J. Dent. 2019, 91, 103220.

- Hu, Z.; Qiu, W.; Yu, Y.; Wu, X.; Fang, F.; Zhu, X.; Xu, X.; Tu, Q.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Morgan, E.F.; et al. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Long Noncoding RNA That Regulates Osteogenesis in Diet-Induced Obesity Mice. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 832460.

- Bahrambeigi, S.; Yousefi, B.; Rahimi, M.; Shafiei-Irannejad, V. Metformin; an old antidiabetic drug with new potentials in bone disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1593–1601.

- Shahrezaee, M.; Salehi, M.; Keshtkari, S.; Oryan, A.; Kamali, A.; Shekarchi, B. In vitro and in vivo investigation of PLA/PCL scaffold coated with metformin-loaded gelatin nanocarriers in regeneration of critical-sized bone defects. Nanomedicine 2018, 14, 2061–2073.

- Ebrahimi, L.; Farzin, A.; Ghasemi, Y.; Alizadeh, A.; Goodarzi, A.; Basiri, A.; Zahiri, M.; Monabati, A.; Ai, J. Metformin-Loaded PCL/PVA Fibrous Scaffold Preseeded with Human Endometrial Stem Cells for Effective Guided Bone Regeneration Membranes. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 222–231.

- Zhang, R.; Liang, Q.; Kang, W.; Ge, S. Metformin facilitates the proliferation, migration, and osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells in vitro. Cell Biol. Int. 2020, 44, 70–79.

- Wang, F.; Qian, H.; Kong, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Chai, Y.; Xu, J.; Kang, Q. Accelerated Bone Regeneration by Astragaloside IV through Stimulating the Coupling of Osteogenesis and Angiogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 1821–1836.

- Kusumbe, A.P.; Ramasamy, S.K.; Adams, R.H. Coupling of angiogenesis and osteogenesis by a specific vessel subtype in bone. Nature 2014, 507, 323–328.

- Aghali, A. Craniofacial Bone Tissue Engineering: Current Approaches and Potential Therapy. Cells 2021, 10, 2993.

- Li, H.; Liao, L.; Hu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, F.; Tian, W.; Guo, W. Identification of Type H Vessels in Mice Mandibular Condyle. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 983–992.

- Solimando, A.G.; Kalogirou, C.; Krebs, M. Angiogenesis as Therapeutic Target in Metastatic Prostate Cancer—Narrowing the Gap Between Bench and Bedside. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 842038.

- Ren, Y.; Luo, H. Metformin: The next angiogenesis panacea? SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211001641.

- Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Hu, K.; Tang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, J. Effects of metformin treatment on serum levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis: A PRISMA-compliant article. Medicine 2017, 96, e8183.

- McCarty, M.F.; Lewis Lujan, L.; Iloki Assanga, S. Targeting Sirt1, AMPK, Nrf2, CK2, and Soluble Guanylate Cyclase with Nutraceuticals: A Practical Strategy for Preserving Bone Mass. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4776.

- Hsu, C.-C.; Peng, D.; Cai, Z.; Lin, H.-K. AMPK signaling and its targeting in cancer progression and treatment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 85, 52–68.

- Tonetti, M.S.; Jepsen, S.; Jin, L.; Otomo-Corgel, J. Impact of the global burden of periodontal diseases on health, nutrition and wellbeing of mankind: A call for global action. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 456–462.

- Ming, P.; Rao, P.; Wu, T.; Yang, J.; Lu, S.; Yang, B.; Xiao, J.; Tao, G. Biomimetic Design and Fabrication of Sericin-Hydroxyapatite Based Membranes with Osteogenic Activity for Periodontal Tissue Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 899293.

- Uskoković, V.; Graziani, V.; Wu, V.M.; Fadeeva, I.V.; Fomin, A.S.; Presniakov, I.A.; Fosca, M.; Ortenzi, M.; Caminiti, R.; Rau, J.V. Gold is for the mistress, silver for the maid: Enhanced mechanical properties, osteoinduction and antibacterial activity due to iron doping of tricalcium phosphate bone cements. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 94, 798–810.

- Zhao, Z.; Sun, Y.; Qiao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xie, X.; Weir, M.D.; Schneider, A.; Xu, H.H.K.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, K.; et al. Human Periodontal Ligament Stem Cell and Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell Co-Culture to Prevascularize Scaffolds for Angiogenic and Osteogenic Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12363.

- Sanchez-Rangel, E.; Inzucchi, S.E. Metformin: Clinical use in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1586–1593.

- Wang, P.; Ma, T.; Guo, D.; Hu, K.; Shu, Y.; Xu, H.H.K.; Schneider, A. Metformin induces osteoblastic differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018, 12, 437–446.

- Al Jofi, F.E.; Ma, T.; Guo, D.; Schneider, M.P.; Shu, Y.; Xu, H.H.K.; Schneider, A. Functional organic cation transporters mediate osteogenic response to metformin in human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 650–659.

- Jang, W.G.; Kim, E.J.; Bae, I.-H.; Lee, K.-N.; Kim, Y.D.; Kim, D.-K.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, C.-H.; Franceschi, R.T.; Choi, H.-S.; et al. Metformin induces osteoblast differentiation via orphan nuclear receptor SHP-mediated transactivation of Runx2. Bone 2011, 48, 885–893.

- Smieszek, A.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Kornicka, K.; Marycz, K. Metformin Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells and Exerts Pro-Osteogenic Effect Stimulating Bone Regeneration. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 482.

- Jia, L.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ma, X.; Xu, X. Metformin promotes osteogenic differentiation and protects against oxidative stress-induced damage in periodontal ligament stem cells via activation of the Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 386, 111717.

- Wang, S.; Xia, Y.; Ma, T.; Weir, M.D.; Ren, K.; Reynolds, M.A.; Shu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Schneider, A.; Xu, H.H.K. Novel metformin-containing resin promotes odontogenic differentiation and mineral synthesis of dental pulp stem cells. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 85–96.

- Shi, Q.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Xu, D. Local Administration of Metformin Improves Bone Microarchitecture and Biomechanical Properties During Ruptured Canine Achilles Tendon-Calcaneus Interface Healing. Am. J. Sport. Med. 2022, 50, 2145–2154.

- Zhang, C.; Hu, K.; Liu, X.; Reynolds, M.A.; Bao, C.; Wang, P.; Zhao, L.; Xu, H.H.K. Novel hiPSC-based tri-culture for pre-vascularization of calcium phosphate scaffold to enhance bone and vessel formation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 79, 296–304.

- Gao, L.; Xu, T.; Huang, G.; Jiang, S.; Gu, Y.; Chen, F. Oral microbiomes: More and more importance in oral cavity and whole body. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 488–500.

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Ruan, J.; Weir, M.D.; Ma, T.; Ren, K.; Schneider, A.; Oates, T.W.; Li, A.; Zhao, L.; et al. Stem cells in the periodontal ligament differentiated into osteogenic, fibrogenic and cementogenic lineages for the regeneration of the periodontal complex. J. Dent. 2020, 92, 103259.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cell & Tissue Engineering

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

16 Jan 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No