| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jinsol Han | -- | 1291 | 2023-01-12 04:13:11 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1291 | 2023-01-12 04:19:38 | | |

Video Upload Options

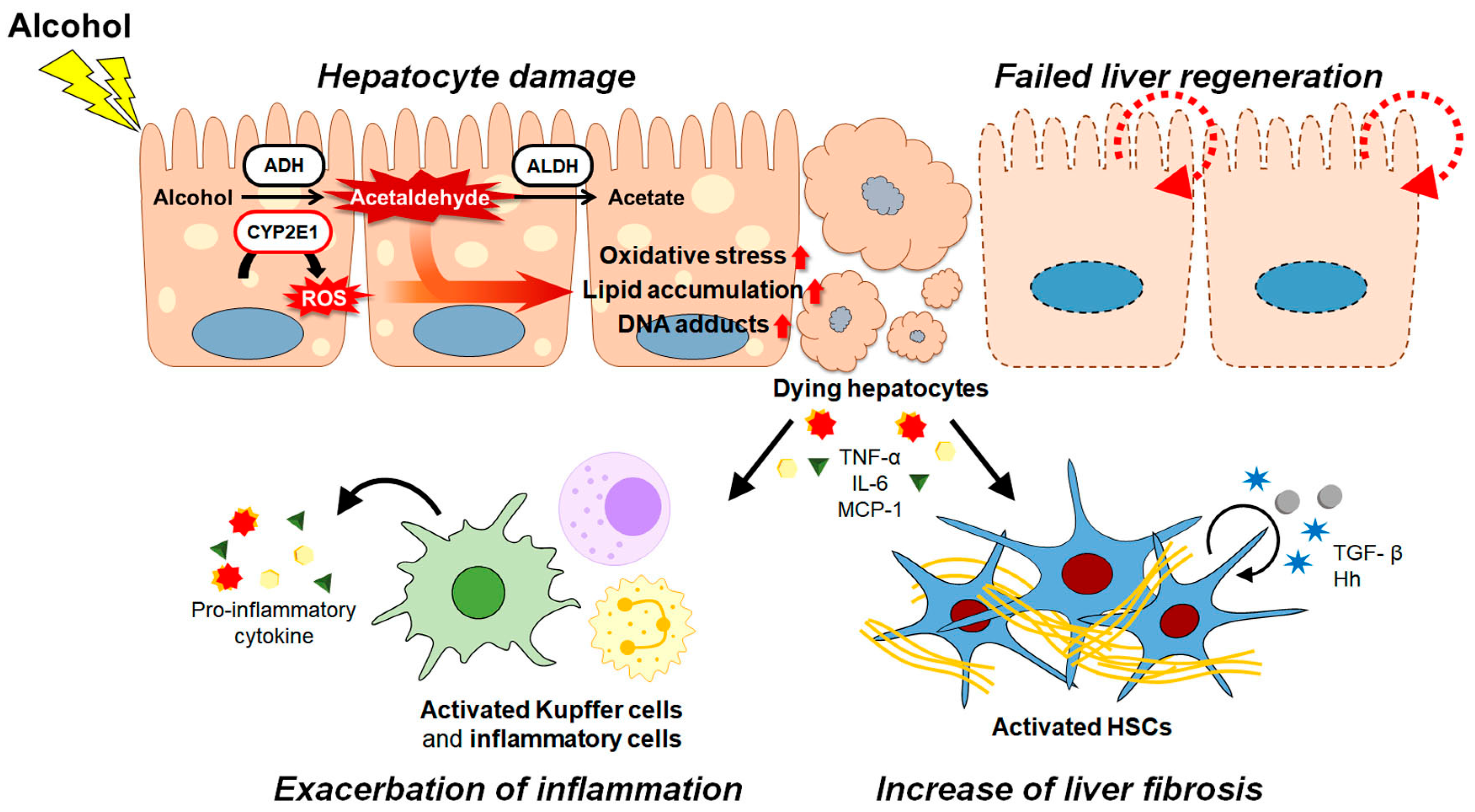

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a globally prevalent chronic liver disease caused by chronic or binge consumption of alcohol. The liver is highly susceptible to alcohol because it is the first organ where alcohol is metabolized, and it has a high level of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes. Metabolization of alcohol in the liver produces various hepatotoxic byproducts and significant oxidative stress on the liver, leading to the large-scale death of hepatocytes . Oxidative stress and excessive cell death exacerbate inflammation in the liver. Prolonged cell damage and inflammation activate hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), which are key players in the development of fibrosis in the liver. ALD encompasses a diverse spectrum, from mild to severe pathologies, including steatosis, steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

1. Introduction

2. Pathogenesis of ALD

References

- Rehm, J. The risks associated with alcohol use and alcoholism. Alcohol Res. Health 2011, 34, 135–143.

- Shield, K.D.; Parry, C.; Rehm, J. Chronic diseases and conditions related to alcohol use. Alcohol Res. 2013, 35, 155–173.

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global Burden of Disease and the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 10.

- Carvalho, A.F.; Heilig, M.; Perez, A.; Probst, C.; Rehm, J. Alcohol use disorders. Lancet 2019, 394, 781–792.

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global Burden of Alcohol Use Disorders and Alcohol Liver Disease. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 99.

- Rehm, J.; Samokhvalov, A.V.; Shield, K.D. Global burden of alcoholic liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 160–168.

- Ramkissoon, R.; Shah, V.H. Alcohol Use Disorder and Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. Alcohol Res. 2022, 42, 13.

- Hyun, J.; Han, J.; Lee, C.; Yoon, M.; Jung, Y. Pathophysiological Aspects of Alcohol Metabolism in the Liver. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5717.

- Cederbaum, A.I. Alcohol metabolism. Clin. Liver Dis. 2012, 16, 667–685.

- Lieber, C.S. Ethanol metabolism, cirrhosis and alcoholism. Clin. Chim. Acta 1997, 257, 59–84.

- Osna, N.A.; Donohue, T.M., Jr.; Kharbanda, K.K. Alcoholic Liver Disease: Pathogenesis and Current Management. Alcohol Res. 2017, 38, 147–161.

- Byun, J.S.; Jeong, W.I. Involvement of hepatic innate immunity in alcoholic liver disease. Immune Netw. 2010, 10, 181–187.

- Chacko, K.R.; Reinus, J. Spectrum of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 2016, 20, 419–427.

- Witkiewitz, K.; Litten, R.Z.; Leggio, L. Advances in the science and treatment of alcohol use disorder. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax4043.

- Deutsch-Link, S.; Curtis, B.; Singal, A.K. COVID-19 and alcohol associated liver disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 1459–1468.

- Vuittonet, C.L.; Halse, M.; Leggio, L.; Fricchione, S.B.; Brickley, M.; Haass-Koffler, C.L.; Tavares, T.; Swift, R.M.; Kenna, G.A. Pharmacotherapy for alcoholic patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2014, 71, 1265–1276.

- Xu, M.; Chang, B.; Mathews, S.; Gao, B. New drug targets for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 2014, 8, 475–480.

- Mitchell, M.C.; Kerr, T.; Herlong, H.F. Current Management and Future Treatment of Alcoholic Hepatitis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 16, 178–189.

- Singal, A.K.; Mathurin, P. Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: A Review. JAMA 2021, 326, 165–176.

- Gao, B.; Bataller, R. Alcoholic liver disease: Pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1572–1585.

- Kong, L.Z.; Chandimali, N.; Han, Y.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, S.U.; Kim, T.D.; Jeong, D.K.; Sun, H.N.; Lee, D.S.; et al. Pathogenesis, Early Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Management of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2712.

- Yang, X.; Meng, Y.; Han, Z.; Ye, F.; Wei, L.; Zong, C. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for liver disease: Full of chances and challenges. Cell Biosci. 2020, 10, 123.

- Nicolas, C.; Wang, Y.; Luebke-Wheeler, J.; Nyberg, S.L. Stem Cell Therapies for Treatment of Liver Disease. Biomedicines 2016, 4, 2.

- Wang, J.; Sun, M.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Li, M. Stem Cell-Based Therapies for Liver Diseases: An Overview and Update. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 16, 107–118.

- Kang, S.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Eom, Y.W.; Baik, S.K. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Treatment of Liver Disease: Present and Perspectives. Gut Liver 2020, 14, 306–315.

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, L. The Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Liver Diseases: Mechanism, Efficacy, and Safety Issues. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 655268.

- Hu, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Bao, Q.; Li, L. Mesenchymal stem cell-based cell-free strategies: Safe and effective treatments for liver injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 377.

- Ding, D.C.; Shyu, W.C.; Lin, S.Z. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011, 20, 5–14.

- Volarevic, V.; Markovic, B.S.; Gazdic, M.; Volarevic, A.; Jovicic, N.; Arsenijevic, N.; Armstrong, L.; Djonov, V.; Lako, M.; Stojkovic, M. Ethical and Safety Issues of Stem Cell-Based Therapy. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 36–45.

- Lee, C.; Kim, M.; Han, J.; Yoon, M.; Jung, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Influence Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells, and Constitute a Promising Therapy for Liver Fibrosis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1598.

- Holford, N.H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ethanol. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1987, 13, 273–292.

- Louvet, A.; Mathurin, P. Alcoholic liver disease: Mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 231–242.

- Lu, Y.; Cederbaum, A.I. CYP2E1 and oxidative liver injury by alcohol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 723–738.

- Leung, T.M.; Nieto, N. CYP2E1 and oxidant stress in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, 395–398.

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462.

- Migdal, C.; Serres, M. Reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress. Med. Sci. 2011, 27, 405–412.

- Cichoż-Lach, H.; Michalak, A. Oxidative stress as a crucial factor in liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 8082–8091.

- Jeon, S.; Carr, R. Alcohol effects on hepatic lipid metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 470–479.

- Baraona, E.; Lieber, C.S. Effects of ethanol on lipid metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 1979, 20, 289–315.

- Tan, H.K.; Yates, E.; Lilly, K.; Dhanda, A.D. Oxidative stress in alcohol-related liver disease. World J. Hepatol. 2020, 12, 332–349.

- Dey, A.; Cederbaum, A.I. Alcohol and oxidative liver injury. Hepatology 2006, 43, S63–S74.

- Wu, D.; Cederbaum, A.I. Alcohol, oxidative stress, and free radical damage. Alcohol Res. Health 2003, 27, 277–284.

- Wu, D.; Zhai, Q.; Shi, X. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress and cell responses. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 21, S26–S29.

- Tsermpini, E.E.; Plemenitaš Ilješ, A.; Dolžan, V. Alcohol-Induced Oxidative Stress and the Role of Antioxidants in Alcohol Use Disorder: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1374.

- Hoek, J.B.; Cahill, A.; Pastorino, J.G. Alcohol and mitochondria: A dysfunctional relationship. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 2049–2063.

- Mantena, S.K.; King, A.L.; Andringa, K.K.; Eccleston, H.B.; Bailey, S.M. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of alcohol- and obesity-induced fatty liver diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 1259–1272.

- Abdallah, M.A.; Singal, A.K. Mitochondrial dysfunction and alcohol-associated liver disease: A novel pathway and therapeutic target. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 26.

- Lv, Y.; So, K.F.; Xiao, J. Liver regeneration and alcoholic liver disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 567.

- Diehl, A.M. Recent events in alcoholic liver disease V. effects of ethanol on liver regeneration. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005, 288, G1–G6.

- Michalopoulos, G.K.; Bhushan, B. Liver regeneration: Biological and pathological mechanisms and implications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 40–55.

- Kiseleva, Y.V.; Antonyan, S.Z.; Zharikova, T.S.; Tupikin, K.A.; Kalinin, D.V.; Zharikov, Y.O. Molecular pathways of liver regeneration: A comprehensive review. World J. Hepatol. 2021, 13, 270–290.

- Horiguchi, N.; Ishac, E.J.; Gao, B. Liver regeneration is suppressed in alcoholic cirrhosis: Correlation with decreased STAT3 activation. Alcohol 2007, 41, 271–280.

- Duguay, L.; Coutu, D.; Hetu, C.; Joly, J.G. Inhibition of liver regeneration by chronic alcohol administration. Gut 1982, 23, 8–13.

- Kawaratani, H.; Tsujimoto, T.; Douhara, A.; Takaya, H.; Moriya, K.; Namisaki, T.; Noguchi, R.; Yoshiji, H.; Fujimoto, M.; Fukui, H. The effect of inflammatory cytokines in alcoholic liver disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 495156.

- Neuman, M.G. Cytokines—Central factors in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Res. Health 2003, 27, 307–316.

- Zeng, T.; Zhang, C.L.; Xiao, M.; Yang, R.; Xie, K.Q. Critical Roles of Kupffer Cells in the Pathogenesis of Alcoholic Liver Disease: From Basic Science to Clinical Trials. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 538.

- Horiguchi, N.; Wang, L.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Park, O.; Jeong, W.I.; Lafdil, F.; Osei-Hyiaman, D.; Moh, A.; Fu, X.Y.; Pacher, P.; et al. Cell type-dependent pro- and anti-inflammatory role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in alcoholic liver injury. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 1148–1158.

- Nowak, A.J.; Relja, B. The Impact of Acute or Chronic Alcohol Intake on the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Alcohol-Related Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9407.

- Koyama, Y.; Brenner, D.A. Liver inflammation and fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 55–64.

- Seki, E.; Schwabe, R.F. Hepatic inflammation and fibrosis: Functional links and key pathways. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1066–1079.

- Brenner, D.A. Molecular pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2009, 120, 361–368.

- Dhar, D.; Baglieri, J.; Kisseleva, T.; Brenner, D.A. Mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its role in liver cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 96–108.

- Lee, U.E.; Friedman, S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011, 25, 195–206.

- Higashi, T.; Friedman, S.L.; Hoshida, Y. Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2017, 121, 27–42.

- Jung, Y.; Brown, K.D.; Witek, R.P.; Omenetti, A.; Yang, L.; Vandongen, M.; Milton, R.J.; Hines, I.N.; Rippe, R.A.; Spahr, L.; et al. Accumulation of hedgehog-responsive progenitors parallels alcoholic liver disease severity in mice and humans. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 1532–1543.

- Kurys-Denis, E.; Prystupa, A.; Luchowska-Kocot, D.; Krupski, W.; Bis-Wencel, H.; Panasiuk, L. PDGF-BB homodimer serum level—A good indicator of the severity of alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 80–85.

- Flisiak, R.; Pytel-Krolczuk, B.; Prokopowicz, D. Circulating transforming growth factor β1 as an indicator of hepatic function impairment in liver cirrhosis. Cytokine 2000, 12, 677–681.