Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tingtao Chen | -- | 2759 | 2023-01-10 06:03:04 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | + 1 word(s) | 2760 | 2023-01-10 08:31:09 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | -1 word(s) | 2759 | 2023-01-11 01:41:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ma, L.; Tu, H.; Chen, T. Application of Postbiotics in Improving Human Health. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39937 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Ma L, Tu H, Chen T. Application of Postbiotics in Improving Human Health. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39937. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Ma, Linxi, Huaijun Tu, Tingtao Chen. "Application of Postbiotics in Improving Human Health" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39937 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Ma, L., Tu, H., & Chen, T. (2023, January 10). Application of Postbiotics in Improving Human Health. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39937

Ma, Linxi, et al. "Application of Postbiotics in Improving Human Health." Encyclopedia. Web. 10 January, 2023.

Copy Citation

In the 21st century, compressive health and functional foods are advocated by increasingly more people in order to eliminate sub-health conditions. Probiotics and postbiotics have gradually become the focus of scientific and nutrition communities. “Postbiotic” has been defined as a “preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host”.

postbiotics

probiotics

comprehensive health

1. Development History of the Concept “Postbiotics”

The concept that non-living microorganisms might improve or maintain health is not new, and several different terms have been used to describe these compounds, although postbiotic has been the most commonly mentioned term in the last 10 years [1].

Scientific evidence that inactivated microorganisms have a favorable impact on human health has been steadily published in the literature since 2009 [2]. In 2011, scientists introduced the term “paraprobiotic” sometimes known as “ghost probiotics” to describe the application of inactivated microbial cells or cell fractions that when delivered in sufficient proportions, might offer a health benefit to the consumer [3]. Research in 2016 worked on paraprobiotic Lactobacillus, which clearly affected intestinal functionality due to the brain-gut interaction when continuously ingested [4]. Murata et al. conducted research on the effects of paraprobiotic Lactobacillus supplementation on common cold symptoms and mental states in 2018 [5]. Meanwhile, Deshpande reviewed current evidence indicating that paraprobiotics could be secure substitutes for probiotics in preterm infants by high-quality pre-clinical and clinical research [6]. Based on published clinical trial data up to 2018, Kanauchi described immune defense mechanisms and potential uses of paraprobiotics against viral infections [2]. The term “para-psychobiotic” also entered the field in 2017 in research exploring the effects of para-psychobiotic Lactobacillus on overstressed symptoms and sleep quality improvement [7].

Shenderov provided the first definition of “metabiotics” in 2013. Metabiotics are the structural components of probiotic microorganisms with or without their metabolites and signaling molecules which can optimize host-specific physiological functions, regulators, metabolic and behavior reactions associated with the indigenous microbiota [8]. Sharma’s clinical research from 2020 revealed that the isolated probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus produced metabiotics with antigenotoxic and cytotoxic properties against colon cancer [9]. The term “metabiotics” in the research mentioned above refers to a cell-free supernatant, which was collected by cold centrifuging overnight grown LAB cultures.

Heat treatments of bacterial suspensions can be manipulated in temperatures ranging from 70 to 100 °C. The method known as tyndallization, created by the scientist Dr. John Tyndall during the eighteenth century, allows for the inactivation of certain substances when heat treatments are combined with incubation periods at lower temperatures (ambient, cooling, or freezing temperatures) [10][11]. Probiotics are sterilized and suppressed to secrete active metabolites during the tyndallization process. The therapeutic benefits of “tyndallized probiotics” were verified in tyndallized L. rhamnosus for the first time for its therapeutic benefits on atopic dermatitis in 2016 [12]. In a study done in 2017, tyndallized probiotics are also discussed in the treatment of chronic diarrhea with gelatin tannate. Live probiotics that can generate active metabolites and tyndallized probiotics are two distinct forms of biological response modifiers, according to Lopetuso. Unable to reproduce, there is no risk for tyndallized probiotics to inherit antibiotic resistance genes or to induce sepsis [13]. Tyndallized probiotics and purified components exhibit probiotic capabilities, constituting a new generation of safer and more stable products, according to a review by Pique, et al. [14].

In 2018, Jurkiewicz et al. established the preventative effects of respiratory tract infections using “bacterial lysates” and combinations of numerous bacterial species which are responsible for respiratory tract inflammations to some extent [15].

2. Mechanisms Driving Postbiotic Efficacy

2.1. Protective Modulation against Pathogens

Although postbiotics influence microbiota temporarily, for the most part, they could indeed play a significant mechanistic role. According to in vivo research, molecules contained in postbiotics, namely lactic acid and bacteriocins, may have direct antimicrobial properties. For instance, organic acids belonging to lactic acid bacteria, bifidobacterial and other postbiotic strains primarily exert antimicrobial efficiency against Gram-negative pathogens, which has a dose-dependent effect [16]. The antibacterial action of the cell-free supernatants is thought to be mostly due to bacteriocins [17], for example, supernatants derived from the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium were also verified to have antibacterial properties against the invasion of enteroinvasive E. coli [18]. Different Bifidobacterium strains have produced bifidocins, which have a wide spectrum of bactericidal action against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as certain yeasts. Additionally, when exposed to exopolysaccharides (EPS) isolated from Bifidobacterium bifidum, lactobacilli and other anaerobic bacteria grew more readily while enterobacteria, enterococci, or Bacteroides fragilis are inhabited [19]. The well-known antibacterial metabolite reuterin, which is generated by Lactobacillus reuteri, is assumed to function by oxidizing thiol groups in pathogenic gut bacteria [16][20]. Co-aggregation with Helicobacter pylori has reportedly been suggested as another potential underlying mechanism for such an action of lactobacilli-contained postbiotics products [21].

The biofilms of pathogenic bacteria are one of the serious hazards to the medical fraternity. Biofilm appears to be the primary cause of pathogenesis and treatment failure because of the antimicrobial resistance enclosed in the biofilm matrix [22]. Through inhibiting the production of biofilms and deconstructing already-formed biofilms, the pure teichoic acids isolated from Lactobacillus strains have exhibited inhibitory effects on biofilm formation of oral or enteric pathogens including Streptococcus mutans, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis [23][24][25]. Biosurfactants that are produced extracellularly or attached to cell walls have the amphiphilic feature, which helps deconstruct existing biofilms or prevents biofilm formation. Additionally, the features of wetting, foaming, and emulsification prevent bacteria from adhering to, establishing themselves in, and subsequently communicating in the biofilms [26].

2.2. Fortify the Epithelial Barrier

Certain postbiotics enhance mucosal barrier function through the alteration of secreted proteins. When administrating the active and heat-killed L. rhamnosus to mice with colitis, protection against the rise in mucosal permeability and restoration of barrier function can be observed, which may be attributed to the upregulation of myosin light-chain kinase and zonula occludens-1 in intestinal epithelial cells [27]. Synergism of mucosal protectors and postbiotics has been verified in intestinal cell models. The same combination, which resulted in an increase in transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) and a decrease in paracellular flux, was also evaluated in CacoGoblet® cells that had been exposed to E. coli [28]. Moreover, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) modulate the trans-permeability in Caco-2 cells through similar mechanisms, enhancing TEER values and the expression of tight junction protein genes [29][30].

Purified EPS from lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria demonstrated the defense against infections in several previous research papers [17][31]. According to some publications, the antibacterial properties of EPS-containing postbiotics may be connected to the formation of a protective biofilm that protects the host epithelium from pathogens or their toxins [31].

2.3. Modulation of Immune Responses

According to research by Tejada-Simon and Pestka, probiotic bacteria’s whole inactivated cells, cell components, as well as cytoplasmic fractions activate macrophages to produce cytokines and nitric oxide, thus indicating that bioactive substances may be present throughout the probiotic cells [32]. These contents discuss the mechanism of the postbiotics regarding the modulation of immune responses in three dimensions: whole inactivated cells, bacterial components and metabolites.

Certain whole-cell postbiotic products of Lactobacillus have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory (downregulation of IL-6, TNF- α and upregulation of IL-10) and anti-oxidative (removal of free radicals) properties in vitro and in vivo experimental animal models [33]. ILs are immune-glycoproteins and are involved in inflammatory responses by modulating multiple growths and the activation progress of immune cells [34]. For example, heat-treated Bifidobacterium longum as a whole-cell postbiotic has demonstrated various barrier protection properties, such as antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and the inhibition of bacterial colonization [35].

With the exception of external bacterial products, the structural elements, especially the cell envelope, which is the outermost structure that immune system cells initially interact with, should play a significant role in mediating immunomodulatory activity. In immunomodulation, toll-like receptors (TLRs) are appropriate and the most common targets for ligand-drug discovery strategies, which make postbiotic products possible in inflammatory diseases and autoimmune disorders [36]. Peptidoglycan (PGN) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) extracted from bacteria have been the subject of several investigations, which have shown that both molecules stimulate the immune system in a receptor-dependent manner. The primary sensors of the innate immune system are specialized conserved pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on host cell membranes, involving TLRs and the nucleotide-binding domain (NOD) proteins (or NOD-like receptors, NLRs), which recognize PGN and LPS as ligands associated with pathogens [37]. Teichoic acids (TAs) can be covalently bonded to the cytoplasmic membrane or peptidoglycan (wall teichoic acids, WTAs) (lipoteichoic acids, LTAs). It has been suggested that TLR2 is the mechanism by which TAs from lactobacilli cause proinflammatory reactions. Additionally, it has been indicated that symbiotic intestinal bacteria and Gram-positive probiotics regulate the immune response to pathogens via their TAs, limiting an excessive inflammatory response [38]. The surface layer (S-layer), consisting of the self-assembly of protein or glycoprotein subunits on the outer surface, allows lactobacilli to stimulate the host immune system. In a study conducted by Konstantinov, L. acidophilus SlpA was recognized and bound to a C-type lectin receptor existing on both macrophages and dendritic cells [39]. Indeed, lactobacilli absent of S-layer proteins showed relatively inadequate adhesion ability to the enterocyte.

Finally, genomic DNA also enables postbiotics to interact with the host immune system. Unmethylated CpG sequences contained in prokaryotic DNA have immunogenicity properties in vitro and in vivo, according to convincing published literature [40]. Researchers from the same period observed that bacterial genomic DNA extracted from pure bifidobacterial cultures of VSL#3 (a probiotic commercial product) affected cytokine production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), with the tendency towards a low level of IL-1b and a high level of IL-10 [41]. An in vivo mouse investigation also validated the anti-inflammatory properties of genomic DNA from VSL#3, revealing that TLR9 signaling was crucial in mediating such anti-inflammatory response [42].

3. Applications of Postbiotics in Different Fields

3.1. Applications in the Food Industry

Fermentation is the most prevalent process with applications of postbiotics, and strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are commonly used as producer strains [43]. The dairy industry benefits greatly from the EPS of specific strains of dairy starter cultures because EPS has significant control over the rheological characteristics of fermented dairy products and lowers their moisture content [44]. Moreover, postbiotics from Lactobacillus plantarum can exert efficacy as a bio-preservative to extend the shelf life of soybeans [45]. Combining the above two kinds of application, MicroGARD is a commercial preparation made by Danisco that has received FDA approval and is utilized as a premier biopreservative in extensive dairy and food matrices. It is a fermented version of Propionibacterium freudenreichii subsp. Shermanii found in skim milk [46]. Other novel approach involves increasing vitamin B and decreasing toxic components during probiotic-induced fermentation [43].

3.2. Pharmaceutical Applications

Many postbiotics products in the experimental research stage and not being applied to the clinic yet, also show great application potential. Giordani B et al. in 2019 conducted research and discovered that the biosurfactants of L. gasseri had antibiofilm capacity against methicil-lin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Another example is a heat-stabilized acidophilus containing medication called Lacteól Fort (Laboratoire du Lacteól du docteur Boucard, France), which has been proven effective in the treatment of acute diarrhea and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [47] by randomized controlled trials. At present, industries are intending to place postbiotics into a regular pharmaceutical product matrix because of their stable pharmacodynamic features and beneficial effects in clinical application [48].

3.3. Biomedical Applications

Postbiotics enhancing the effects of vaccination in the elderly has been proven by increasingly more evidence, the underlying mechanism of which includes sustainable antibody production and NK-cell activities. Research in 2016 demonstrated that the concentration of antibody to type A/H1N1 and B antigens were improved in an elderly subgroup with heat-killed Lactobacillus paracasei jelly [49]. Moreover, similar to parent probiotics, the use of postbiotics is a promising strategy to treat pediatric infectious diseases in under-five-year-olds because it exerts immunomodulatory as well as antimicrobial effects [50]. Postbiotics are also able to serve as a novel strategy for food allergy in pediatrics because of their unique characteristics against parent live cells [51].

Research demonstrates that the microbiome-metabolome axis in the gastrointestinal tract is affected and therefore graft versus host disease colitis can be alleviated through probiotics or postbiotics application [52]. Similarly, the combination of postbiotic butyrate and active vitamin D could be a possible treatment for infectious and autoimmune colitis [53]. Apart from gastrointestinal diseases, extensive research has proven that specific postbiotic metabolites affect the differentiation and function of CD4+ T cells, with results indicating that postbiotics could be a promising perspective to treat allergic rhinitis [54]. Moreover, urinary tract infections (UTIs) should be further explored based on the results suggesting that mucosal protectors might lessen the intestinal reservoirs of uropathogenic E. coli strains [55]. Accordingly, some research indicates that metabolites generated by lactobacilli (hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid) act in concert to eradicate uropathogenic organisms in vitro [56][57] and could serve as the foundation for the creation of UTI management products with postbiotics.

Furthermore, various postbiotic molecules have attracted interest because of their wide modulation effects in obesity, coronary artery diseases, and oxidative stress through the capacity to trigger the alleviation of inflammation reactions and pathogen adherence to gastrointestinal tract, etc. Presently, postbiotic preparations have also been granted patents as bio-therapeutics for a specific health benefit of “immune-modulation” [58].

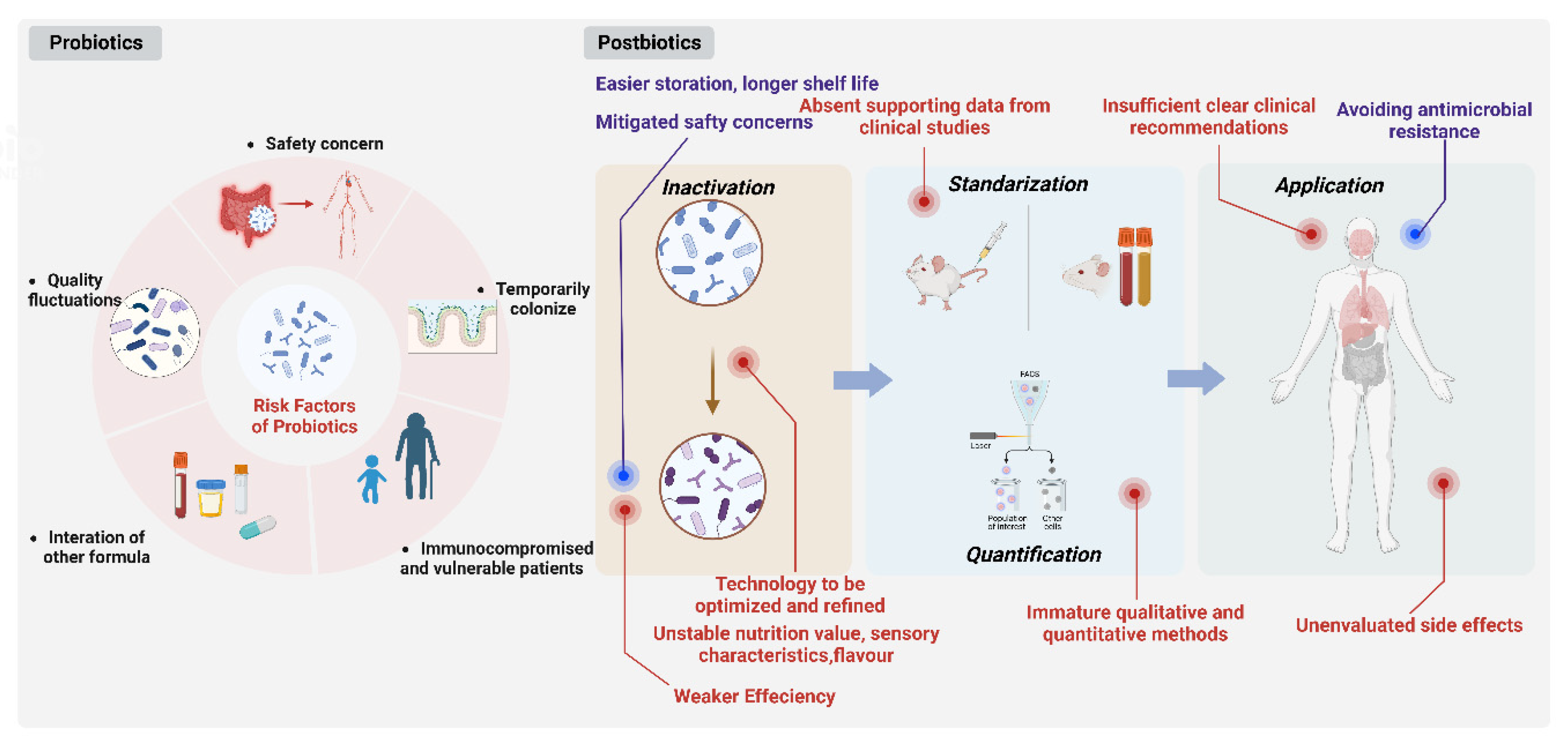

4. Advantages of Postbiotics Compared with Probiotics

The use of non-viable postbiotics as a safer option has gained popularity as safety concerns over the use of live strains have surfaced in certain patient populations, including immunodeficient subjects, infants and vulnerable patients [3][6][59]. They could significantly reduce consumer risk of microbial translocation and infection [60].

Calculating the percentage of dead cells in a probiotic culture that is still viable will be difficult. Therefore, changing percentages of dead cells may be the origin of the variation in responses usually found with living probiotic products. However, it is simple to demonstrate that postbiotics are devoid of any living organisms. Postbiotics-based products would be long-lasting and extremely simple to standardize, making them easier to store, have a longer shelf life and facilitate logistics under extreme environmental conditions. [35][59].

By lowering the likelihood of the transmission of antibiotic-resistant genes, using inactivated bacteria can have significant advantages. Probiotic use is now discussed in terms of antimicrobial resistance prevention techniques [61][62] and the need to stay away from long-term pharmaceutical treatments and their negative effects [61]. The use of non-viable probiotics as an alternative therapy is increasingly accepted due to the high incidence of antibiotic resistance in live probiotic applications (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparison between probiotics and postbiotics in application.

5. Drawbacks of Postbiotics

Postbiotic products have been proven to be a relatively weaker influence on the modulation of intestinal metabolism or gene expression affecting nutrition metabolism when compared with corresponding probiotics. For example, live cells of Bifidobacterium breve M-16V displayed enhanced immunomodulation effects in contrast to postbiotics, which is mainly reflected in the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines in spleen cells and more significant alteration of intestinal metabolism [59].

The type of technology in the inactivation process might relate to products with variable functionality in comparison with the progenitor microbial product according to the microbial inactivation degree achieved. For example, it has been demonstrated that different heat treatments ranging from air drying, freeze drying to spray drying can significantly impact the viability and immunomodulatory properties when dehydrating probiotics [63] On the other hand, volatility in the nutritional value, sensory characteristics and flavors caused by traditional thermal processing including pasteurization, tyndallization and autoclaving frequently occurs, thus establishing a reliable controllable range, and the acceptance of the original product audience requires more investigation [1]. Thermal processing, therefore, may not be the best option, especially when a postbiotic product is used as a food supplement. Emerging technologies such as electric field, ultrasonication, high pressure, ionizing radiation, pulsed light, magnetic field heating and plasma technology [64] could possibly be applied to inactivate microorganisms and generate postbiotics to obtain safe and stable foods with retained overall quality and value.

The composition and quantity of a postbiotic product must be described and measured using appropriate methods. These techniques should be accessible for both quality control at the production site, and for a precise product description that enables duplicate research. An emerging technique, flow cytometry, is now gradually substituting traditional technology such as plate counting for microbial counting and enumeration [65].

Inconsistent, vague, and frequently reliant on patient requests, postbiotic product recommendations also suffer from similar issues, according to a recent study on healthcare providers’ probiotic prescription practices. This means that the patient or the pharmacist made the postbiotics choice based merely on their own experience for a significant portion of the time [14]. It is vital to address the insufficient, clear and specific clinical recommendations and the absence of supporting data from clinical research.

In the group receiving the inactivated L. acidophilus with micronutrients, side effects appear involving severe to moderate dehydration, abdominal distension, and vomiting ranging from mild to severe [66]. Postbiotic therapies’ safety and potential risks have not been thoroughly researched or understood. To ascertain the effects and safety of various postbiotics, additional multicenter studies are required.

References

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667.

- Kataria, J.; Li, N.; Wynn, J.L.; Neu, J. Probiotic microbes: Do they need to be alive to be beneficial? Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 546–550.

- Taverniti, V.; Guglielmetti, S. The immunomodulatory properties of probiotic microorganisms beyond their viability (ghost probiotics: Proposal of paraprobiotic concept). Genes Nutr. 2011, 6, 261–274.

- Sugawara, T.; Sawada, D.; Ishida, Y.; Aihara, K.; Aoki, Y.; Takehara, I.; Takano, K.; Fujiwara, S. Regulatory effect of paraprobiotic Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 on gut environment and function. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2016, 27, 30259.

- Murata, M.; Kondo, J.; Iwabuchi, N.; Takahashi, S.; Yamauchi, K.; Abe, F.; Miura, K. Effects of paraprobiotic Lactobacillus paracasei MCC1849 supplementation on symptoms of the common cold and mood states in healthy adults. Benef. Microbes 2018, 9, 855–864.

- Deshpande, G.; Athalye-Jape, G.; Patole, S. Para-Probiotics for Preterm Neonates-The Next Frontier. Nutrients 2018, 10, 871.

- Nishida, K.; Sawada, D.; Kawai, T.; Kuwano, Y.; Fujiwara, S.; Rokutan, K. Para-psychobiotic Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 ameliorates stress-related symptoms and sleep quality. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 1561–1570.

- Shenderov, B.A. Metabiotics: Novel idea or natural development of probiotic conception. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2013, 24, 20399.

- Sharma, M.; Chandel, D.; Shukla, G. Antigenotoxicity and Cytotoxic Potentials of Metabiotics Extracted from Isolated Probiotic, Lactobacillus rhamnosus MD 14 on Caco-2 and HT-29 Human Colon Cancer Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 72, 110–119.

- Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Bang, J.; Kim, Y.; Beuchat, L.R.; Ryu, J.H. Reduction of Bacillus cereus spores in sikhye, a traditional Korean rice beverage, by modified tyndallization processes with and without carbon dioxide injection. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 55, 218–223.

- Daelemans, S.; Peeters, L.; Hauser, B.; Vandenplas, Y. Recent advances in understanding and managing infantile colic. F1000Research 2018, 7, 1426.

- Lee, S.H.; Yoon, J.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Jeong, D.G.; Park, S.; Kang, D.J. Therapeutic effect of tyndallized Lactobacillus rhamnosus IDCC 3201 on atopic dermatitis mediated by down-regulation of immunoglobulin E in NC/Nga mice. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 60, 468–476.

- Lopetuso, L.; Graziani, C.; Guarino, A.; Lamborghini, A.; Masi, S.; Stanghellini, V. Gelatin tannate and tyndallized probiotics: A novel approach for treatment of diarrhea. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 873–883.

- Pique, N.; Berlanga, M.; Minana-Galbis, D. Health Benefits of Heat-Killed (Tyndallized) Probiotics: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2534.

- Jurkiewicz, D.; Zielnik-Jurkiewicz, B. Bacterial lysates in the prevention of respiratory tract infections. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2018, 72, 1–8.

- Lukic, J.; Chen, V.; Strahinic, I.; Begovic, J.; Lev-Tov, H.; Davis, S.C.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Pastar, I. Probiotics or pro-healers: The role of beneficial bacteria in tissue repair. Wound Repair Regen. 2017, 25, 912–922.

- Sarkar, A.; Mandal, S. Bifidobacteria-Insight into clinical outcomes and mechanisms of its probiotic action. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 192, 159–171.

- Scarpellini, E.; Rinninella, E.; Basilico, M.; Colomier, E.; Rasetti, C.; Larussa, T.; Santori, P.; Abenavoli, L. From Pre- and Probiotics to Post-Biotics: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 37.

- Wu, M.H.; Pan, T.M.; Wu, Y.-J.; Chang, S.-J.; Chang, M.-S.; Hu, C.-Y. Exopolysaccharide activities from probiotic bifidobacterium: Immunomodulatory effects (on J774A.1 macrophages) and antimicrobial properties. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 104–110.

- Schaefer, L.; Auchtung, T.A.; Hermans, K.E.; Whitehead, D.; Borhan, B.; Britton, R.A. The antimicrobial compound reuterin (3-hydroxypropionaldehyde) induces oxidative stress via interaction with thiol groups. Microbiology 2010, 156 Pt 6, 1589–1599.

- Aiba, Y.; Ishikawa, H.; Tokunaga, M.; Komatsu, Y. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of non-living, heat-killed form of lactobacilli including Lactobacillus johnsonii No.1088. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364, 102.

- Nataraj, B.H.; Ali, S.A.; Behare, P.V.; Yadav, H. Postbiotics-parabiotics: The new horizons in microbial biotherapy and functional foods. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 168.

- Jung, S.; Park, O.J.; Kim, A.R.; Ahn, K.B.; Lee, D.; Kum, K.Y.; Yun, C.H.; Han, S.H. Lipoteichoic acids of lactobacilli inhibit Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation and disrupt the preformed biofilm. J. Microbiol. 2019, 57, 310–315.

- Kim, A.R.; Ahn, K.B.; Yun, C.H.; Park, O.J.; Perinpanayagam, H.; Yoo, Y.J.; Kum, K.Y.; Han, S.H. Lactobacillus plantarum Lipoteichoic Acid Inhibits Oral Multispecies Biofilm. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 310–315.

- Ahn, K.B.; Baik, J.E.; Park, O.J.; Yun, C.H.; Han, S.H. Lactobacillus plantarum lipoteichoic acid inhibits biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192694.

- Velraeds, M.M.; van de Belt-Gritter, B.; Busscher, H.J.; Reid, G.; van der Mei, H.C. Inhibition of uropathogenic biofilm growth on silicone rubber in human urine by lactobacilli—A teleologic approach. World J. Urol. 2000, 18, 422–426.

- Miyauchi, E.; Morita, H.; Tanabe, S. Lactobacillus rhamnosus alleviates intestinal barrier dysfunction in part by increasing expression of zonula occludens-1 and myosin light-chain kinase in vivo. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 2400–2408.

- Servi, B.; Ranzini, F. Protective efficacy of antidiarrheal agents in a permeability model of Escherichia coli-infected CacoGoblet® cells. Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 1449–1455.

- Zheng, L.; Kelly, C.J.; Battista, K.D.; Schaefer, R.; Lanis, J.M.; Alexeev, E.E.; Wang, R.X.; Onyiah, J.C.; Kominsky, D.J.; Colgan, S.P. Microbial-Derived Butyrate Promotes Epithelial Barrier Function through IL-10 Receptor-Dependent Repression of Claudin-2. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 2976–2984.

- Peng, L.; Li, Z.R.; Green, R.S.; Holzman, I.R.; Lin, J. Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1619–1625.

- Castro-Bravo, N.; Wells, J.M.; Margolles, A.; Ruas-Madiedo, P. Interactions of Surface Exopolysaccharides from Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus within the Intestinal Environment. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2426.

- Tejada-Simon, M.V.; Pestka, J.J. Proinflammatory cytokine and nitric oxide induction in murine macrophages by cell wall and cytoplasmic extracts of lactic acid bacteria. J. Food Prot. 1999, 62, 1435–1444.

- Behzadi, P.; Sameer, A.S.; Nissar, S.; Banday, M.Z.; Gajdacs, M.; Garcia-Perdomo, H.A.; Akhtar, K.; Pinheiro, M.; Magnusson, P.; Sarshar, M.; et al. The Interleukin-1 (IL-1) Superfamily Cytokines and Their Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 2054431.

- Behzadi, P.; Garcia-Perdomo, H.A.; Karpinski, T.M. Toll-Like Receptors: General Molecular and Structural Biology. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 9914854.

- Martorell, P.; Alvarez, B.; Llopis, S.; Navarro, V.; Ortiz, P.; Gonzalez, N.; Balaguer, F.; Rojas, A.; Chenoll, E.; Ramón, D.; et al. Heat-Treated Bifidobacterium longum CECT-7347: A Whole-Cell Postbiotic with Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Gut-Barrier Protection Properties. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 536.

- Chung, I.C.; OuYang, C.N.; Yuan, S.N.; Lin, H.C.; Huang, K.Y.; Wu, P.S.; Liu, C.Y.; Tsai, K.J.; Loi, L.K.; Chen, Y.J.; et al. Pretreatment with a Heat-Killed Probiotic Modulates the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Attenuates Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer in Mice. Nutrients 2019, 11, 516.

- Philpott, D.J.; Girardin, S.E. The role of Toll-like receptors and Nod proteins in bacterial infection. Mol. Immunol. 2004, 41, 1099–1108.

- Konstantinov, S.R.; Smidt, H.; de Vos, W.M.; Bruijns, S.C.M.; Singh, S.K.; Valence, F.; Molle, D.; Lortal, S.; Altermann, E.; Klaenhammer, T.R.; et al. S layer protein A of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM regulates immature dendritic cell and T cell functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 19474–19479.

- Frece, J.; Kos, B.; Svetec, I.K.; Zgaga, Z.; Mrsa, V.; Susković, J. Importance of S-layer proteins in probiotic activity of Lactobacillus acidophilus M92. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 285–292.

- Rachmilewitz, D.; Karmeli, F.; Takabayashi, K.; Hayashi, T.; Leider-Trejo, L.; Lee, J.; Leoni, L.M.; Raz, E. Immunostimulatory DNA ameliorates experimental and spontaneous murine colitis. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 1428–1441.

- Lammers, K.M.; Brigidi, P.; Vitali, B.; Gionchetti, P.; Rizzello, F.; Caramelli, E.; Matteuzzi, D.; Campieri, M. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotic bacteria DNA: IL-1 and IL-10 response in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2003, 38, 165–172.

- Rachmilewitz, D.; Katakura, K.; Karmeli, F.; Hayashi, T.; Reinus, C.; Rudensky, B.; Akira, S.; Takeda, K.; Lee, J.; Takabayashi, K.; et al. Toll-like receptor 9 signaling mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics in murine experimental colitis. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, 520–528.

- Thorakkattu, P.; Khanashyam, A.C.; Shah, K.; Babu, K.S.; Mundanat, A.S.; Deliephan, A.; Deokar, G.S.; Santivarangkna, C.; Nirmal, N.P. Postbiotics: Current Trends in Food and Pharmaceutical Industry. Foods 2022, 11, 3094.

- Behare, P.; Singh, R.P.; Singh, R.P. Exopolysaccharide-producing mesophilic lactic cultures for preparation of fat-free Dahi—An Indian fermented milk. J. Dairy Res. 2009, 76, 90–97.

- Rather, I.A.; Seo, B.; Kumar, V.R.; Choi, U.H.; Choi, K.H.; Lim, J.; Park, Y.H. Isolation and characterization of a proteinaceous antifungal compound from Lactobacillus plantarum YML 007 and its application as a food preservative. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 57, 69–76.

- Makhal, S.; Kanawjia, S.K.; Giri, A. Effect of microGARD on keeping quality of direct acidified Cottage cheese. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 936–943.

- Bermudez-Brito, M.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Muñoz-Quezada, S.; Gómez-Llorente, C.; Gil, A. Probiotic mechanisms of action. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 61, 160–174.

- Aguilar-Toalá, J.E.; Garcia-Varela, R.; Garcia, H.S.; Mata-Haro, V.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Hernández-Mendoza, A. Postbiotics: An evolving term within the functional foods field. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 75, 105–114.

- Akatsu, H. Exploring the Effect of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Postbiotics in Strengthening Immune Activity in the Elderly. Vaccines 2021, 9, 136.

- Mantziari, A.; Salminen, S.; Szajewska, H.; Malagon-Rojas, J.N. Postbiotics against Pathogens Commonly Involved in Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1510.

- Riwes, M.; Reddy, P. Short chain fatty acids: Postbiotics/metabolites and graft versus host disease colitis. Semin. Hematol. 2020, 57, 1–6.

- Rad, A.H.; Maleki, L.A.; Kafil, H.S.; Abbasi, A. Postbiotics: A novel strategy in food allergy treatment. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 492–499.

- Huang, F.-C.; Huang, S.-C. The Combined Beneficial Effects of Postbiotic Butyrate on Active Vitamin D3-Orchestrated Innate Immunity to Salmonella Colitis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1296.

- Capponi, M.; Gori, A.; De Castro, G.; Ciprandi, G.; Anania, C.; Brindisi, G.; Tosca, M.; Cinicola, B.L.; Salvatori, A.; Loffredo, L.; et al. (R)Evolution in Allergic Rhinitis Add-On Therapy: From Probiotics to Postbiotics and Parabiotics. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5154.

- Fraile, B.; Alcover, J.; Royuela, M.; Rodríguez, D.; Chaves, C.; Palacios, R.; Piqué, N. Xyloglucan, hibiscus and propolis for the prevention of urinary tract infections: Results of in vitro studies. Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 721–731.

- Atassi, F.; Servin, A.L. Individual and co-operative roles of lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide in the killing activity of enteric strain Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC933 and vaginal strain Lactobacillus gasseri KS120.1 against enteric, uropathogenic and vaginosis-associated pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 304, 29–38.

- Sihra, N.; Goodman, A.; Zakri, R.; Sahai, A.; Malde, S. Nonantibiotic prevention and management of recurrent urinary tract infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2018, 15, 750–776.

- Singh, A.; Vishwakarma, V.; Singhal, B. Metabiotics: The Functional Metabolic Signatures of Probiotics: Current State-of-Art and Future Research Priorities—Metabiotics: Probiotics Effector Molecules. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 147–189.

- Adams, C.A. The probiotic paradox: Live and dead cells are biological response modifiers. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010, 23, 37–46.

- Cross, M.L.; Ganner, A.; Teilab, D.; Fray, L.M. Patterns of cytokine induction by gram-positive and gram-negative probiotic bacteria. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 173–180.

- Piqué, N.; Del Carmen Gómez-Guillén, M.; Montero, M.P. Xyloglucan, a Plant Polymer with Barrier Protective Properties over the Mucous Membranes: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 673.

- Costelloe, C.; Metcalfe, C.; Lovering, A.; Mant, D.; Hay, A.D. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010, 340, c2096.

- Iaconelli, C.; Lemetais, G.; Kechaou, N.; Chain, F.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Langella, P.; Gervais, P.; Beney, L. Drying process strongly affects probiotics viability and functionalities. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 214, 17–26.

- Charoux, C.M.G.; Free, L.; Hinds, L.M.; Vijayaraghavan, R.K.; Daniels, S.; O’Donnell, C.P.; Tiwari, B.K. Effect of non-thermal plasma technology on microbial inactivation and total phenolic content of a model liquid food system and black pepper grains. LWT 2020, 118, 108716.

- Chiron, C.; Tompkins, T.A.; Burguière, P. Flow cytometry: A versatile technology for specific quantification and viability assessment of micro-organisms in multistrain probiotic products. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 124, 572–584.

- Malagón-Rojas, J.N.; Mantziari, A.; Salminen, S.; Szajewska, H. Postbiotics for Preventing and Treating Common Infectious Diseases in Children: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 389.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.4K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

11 Jan 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No